Abstract

Background

Beat to beat alternans of cellular repolarization is closely linked to ventricular arrhythmias in humans. We hypothesized that sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium reuptake by SERCA2a plays a central role in the mechanism of cellular alternans and increasing SERCA2a gene expression will retard the development of cellular alternans.

Methods and Results

In-vivo gene transfer of a recombinant adenoviral vector with the transgene for SERCA2a (Ad.SERCA2a) was performed in young guinea pigs. Isolated myocytes transduced with Ad.SERCA2a exhibited improved sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ reuptake (p< 0.05) and were markedly resistant to Ca-ALT (p< 0.05) under repetitive constant action potential clamp conditions (i.e. when APD-ALT was prevented) proving that SR Ca2+ cycling is an important mechanism in the development of cellular alternans. Similarly, SERCA2a overexpression in the intact heart demonstrated significant resistance to APD-ALT when compared control hearts (HR threshold 484±25 bpm vs 396±11 bpm, p< 0.01), with no change in APD restitution slope. Importantly, SERCA2a overexpression produced a 4-fold reduction in susceptibility to alternans-mediated ventricular arrhythmias (p< 0.05).

Conclusions

These data provide new evidence that SR Ca2+ reuptake directly modulates susceptibility to cellular alternans. Moreover, SERCA2a overexpression suppresses cellular alternans, interrupting an important pathway to cardiac fibrillation in the intact heart.

Keywords: alternans, action potentials, intracellular calcium, adenoviral gene transfer, repolarization, arrhythmia

INTRODUCTION

Although ventricular arrhythmias are the most common cause of cardiovascular mortality, the mechanisms responsible for triggering electrical instability in the heart are poorly understood. Cardiac alternans is a repetitive beat-to-beat fluctuation of cellular repolarization that is closely associated with ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in a wide variety of experimental 23; 36; 43 and clinical 33 40 conditions. It is clear that alternans arises from alternation of action potential duration (APD-ALT) at the level of the single cell, 12 17 and it has been proposed that APD-ALT arises secondarily from an effect on calcium-sensitive electrogenic sarcolemmal currents during cytosolic calcium alternans (Ca-ALT) 9; 42 7; 13. Therefore, understanding the cellular and molecular basis for Ca-ALT can provide important and novel insights into mechanisms of ventricular arrhythmias.

It is generally accepted that cellular alternans occurs when the heart rate exceeds capabilities of the cardiac myocyte to cycle calcium on a beat by beat basis. This hypothesis predicts that during steady-state (i.e. resting heart rate) the amount of Ca2+ released from the SR to initiate cardiac contraction must be matched by the Ca2+ reclaimed from the cytoplasm, primarily by SERCA2a. Any sustained disturbance in the myocytes ability to load or release SR Ca2+ presumably leads to the development of Ca2+ alternans. For example, instabilities of SR Ca2+ release through the RyR release channel either with 7 or without 13 27 fluctuations of SR Ca2+ content has been argued as one mechanism for cellular alternans. An alternative and equally compelling hypothesis implicates impaired SR reuptake in the mechanism of Ca-ALT 43. However, the specific SR Ca2+ cycling protein(s) underlying the molecular basis for cellular alternans are unknown. Recent data from our laboratory provide important insight into the molecular basis for cellular alternans. In particular, cardiac myocytes that are most susceptible to APD-ALT exhibit reduced expression of the SERCA2a and delayed SR Ca2+ reuptake 42 19. These findings led us to hypothesize in the present study that SERCA2a function plays a critical role in the initiation of cellular alternans.

Identification of a molecular basis for cardiac alternans has been challenging because of difficulties in distinguishing experimentally the complex interactions between sarcolemmal and sarcomeric ionic fluxes using relatively non-specific pharmacological probes. However, gene transfer techniques can be utilized to alter the expression of single proteins and in this way, disease mechanisms can be elucidated and potential therapeutic targets identified. Therefore, to test our hypothesis that SERCA2a function is an important mechanism in the initiation of cellular alternans, we performed in vivo gene transfer of Ad.SERCA2a.GFP in the guinea pig heart. Over-expression of SERCA2a significantly inhibited cellular alternans and susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias in the intact beating guinea pig heart. These data establish a molecular mechanism for arrhythmogenic cardiac alternans. Specifically, enhancement of SERCA2a gene expression will diminish susceptibility to cellular alternans, thereby interrupting an important pathway to cardiac fibrillation in the intact heart.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vivo gene delivery

Recombinant adenoviral vectors were used with cytomegalovirus-driven expression cassettes for SERCA2a (Ad.SERCA2a) with a second cassette in each adenovirus containing GFP substituted for E1 by means of homologous recombination as previously described 6. Control adenoviral vectors were used with cytomegalovirus-driven expression cassettes for GFP (Ad.GFP) or β-galactosidase (Ad. β-gal).

Experiments were carried out in accordance with the United States Public Health Service guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. In-vivo gene transfer was performed using a modified cross-clamping method 4. Briefly, animals were anesthetized (Ketamine, Xylazine, Acepromazine and Atropine) and mechanically ventilated (2.0 cc tidal volume at 50 cycles per minute) via a tracheostomy (18 g tube). An anterior thoracotomy was performed and the pulmonary artery and aorta isolated. A 27 gauge catheter was advanced from the apex to the aortic root. Subsequently, the aorta and pulmonary artery were cross-clamped for 50–60 seconds and the virus solution (1×1012 particle/ml Ad.SERCA2a.GFP, n=7; 1×1012 particle/ml Ad.GFP. n=5; or 1.2×1011 particle/ml Ad.βgal, n=3; plus 75ug/ml of Nitroglycerin) was injected. The animals were placed on a heating pad (42°C), the chest closed and intrathoracic air evacuated. Animals were extubated upon spontaneous breathing and closely observed until fully awake.

Efficiency of in vivo gene transfer

Qualitative assessment of transduction efficiency

Seventy-two hours after gene transfer with β-galactosidase animals (n=3) were euthanized with pentobarbital. The heart was rapidly removed, flushed with phosphate-buffered saline, transversely sliced into 3 pieces used for x-gal staining 8. This procedure was performed to assess the regional distribution and homogeneity of gene delivery in the intact heart.

Quantitative assessment of transduction efficiency

Seventy-two hours after gene transfer myocytes isolated from the left ventricular free wall were examined by fluorescence microscopy to calculate transduction efficiency. Efficiency is reported as the percentage of all myocytes in the microscope field that fluoresced green.

SERCA2a protein expression

Myocytes isolated from the transmural left ventricular free wall of both SERCA2a transduced hearts and age-matched control hearts, as previously described, were used for western blotting to determine the relative expression levels of SERCA2a 42. Cardiac homogenates (10µg for SERCA2) were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Blots were probed with rabbit anti-SERCA antibody (Dr Periasamy, Ohio State University). They were then treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody. Protein bands were quantified using ImageQuant software.

Isolated Myocyte Studies

Seventy-two hours after in vivo gene transfer isolated myocyte electrophysiological studies were performed. Membrane voltage and intracellular calcium were measured simultaneously using perforated patch technique and the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator indo-1AM. Myocytes transduced with Ad.SERCA2a and Ad.GFP (i.e. control) were confirmed using GFP fluorescence. As there were no statistical differences in calcium cycling characteristics and alternans susceptibility between myocytes isolated from untreated hearts and Ad.GFP transduced hearts, data are presented as a combined control group.

Patch clamp recordings

The amphotericin perforated patch technique was used to obtain whole-cell recordings of membrane voltage under current clamp conditions as described previously 3. Briefly, the cells were bathed in a chamber continuously perfused with Tyrode’s solution composed of (mmol/L) NaCl 137, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 2.0, MgSO4 1.0, Glucose 10, HEPES 10, pH to 7.35 with NaOH. Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate capillary glass and lightly fire-polished to resistance 0.9–1.5 MΩ when filled with electrode solution composed of (mmol/L) aspartic acid 120, KCl 20, NaCl 10, MgCl2 2, HEPES 5, and 240 µg/ml of amphotericin-B (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), pH7.3. A gigaseal was rapidly formed. Typically, 10 min later, amphotericin pores lowered the resistance sufficiently to current clamp the cells. Myocytes were paced using a 1.5 –2 diastolic threshold 5 ms current pulse. Experiments were performed at 30°C. Command and data acquisition were operated with an Axopatch 200B patch clamp amplifier controlled by a personal computer using a Digidata 1200 acquisition board driven by pCLAMP 7.0 software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA).

Calcium transient recordings

Intracellular Ca2+ transients were measured simultaneously using the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator indo-1AM as described previously 37. Cells were loaded with indo-1AM by incubating them in Tyrode containing indo-1AM (2uM) (Molecular Probes) and 0.025% (wt/wt) Pluronic F-127 (Molecular Probes) for 30 min at room temperature. The intracellular indo 1 was excited at 355 nm. Fluorescence emitted at 405 and 485 nm was collected by two matched photomultiplier tubes. Data were filtered at 200 Hz and sampled at 1 kHz. The ratio of the intensity of fluorescence emitted at 405 nm over that at 485 nm was calculated after subtraction of background fluorescence as described previously 16. The emission field was restricted to a single cell with the aid of an adjustable window. To determine intracellular calcium concentration, the ratiometric calcium transients were calibrated using the techniques developed by Grynkeiwicz et al. 10. The calibration parameters, Rmin and Rmax, were obtained from isolated myocytes with either a modified calcium-free, Rmin (n = 8) or a calcium-saturated, Rmax (n = 8) Tyrode solution. The modified Rmin solution contained (mM) 132 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 0.05 4-bromo-A-23817; pH 7.05. The modified Rmax solution contained (mM) 132 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 BDM; pH 7.05. Dissociation constant (Kd) = 250 nM and β= 2.5 (8). Calcium concentrations were calculated using the following standard calibration equations 10: [Ca2+]i = Kd *β*((R-Rmin)/(Rmax-R))

Stimulation protocol

Myocytes were stimulated at a baseline stimulation rate of 150 beat per minute (bpm). Following a period of stimulation to establish steady state, measurements were made for the subsequent 20 beats. This protocol was repeated at progressively faster rates until 1:1 capture was lost.

Whole Heart Studies

Whole heart electrophysiological studies were performed in Ad.SERCA2a and control hearts. As there were no statistical differences in alternans magnitude, alternans HR threshold and arrhythmia susceptibility between untreated control (n=5) and sham operated Ad.GFP controls (n=3), data are presented as a combined control group (n=8). Isolated hearts were Langendorff perfused with oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) Tyrode’s solution (in mmol/L: NaCl 130, NaHCO3 25.0, MgSO4 1.2, KCl 4.75, dextrose 5.0, CaCl2 1.25, pH 7.40, 32°C and the endocardial surface was eliminated by a cryoablation procedure described previously 25. This model is highly optimal to study alternans following gene transfer because our current gene delivery technique provides greatest gene transfer to the epicardium (Figure 1A).

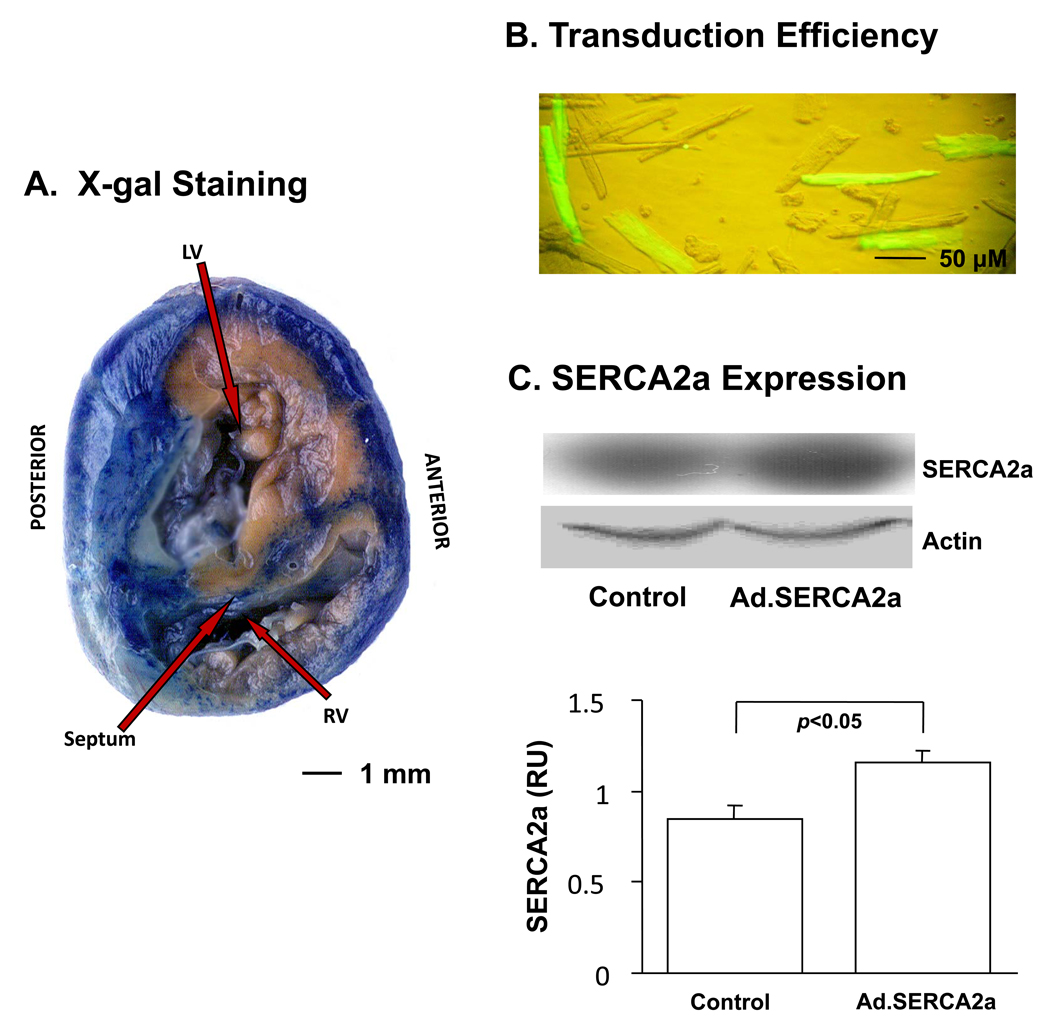

Figure 1.

Gene transfer efficiency 72 hours after in vivo viral transduction. Panel A: Example of X-gal stained cross section of guinea pig ventricles excised 4 days after Ad.β-gal exposure. Panel B: Myocytes isolated from left ventricular free wall of guinea pig heart transduced with Ad.SERCA2.GFP. Fluorescent image shows the GFP transduction efficiency around 30%. Panel C: Example of protein expression. In vivo viral transduction increased SERCA2a expression compared to control (p<0.05).

High resolution optical action potentials were recorded from the anterior surface of the left ventricle using the voltage sensitive dye di-4-ANEPPS (15 µmol/L), as previously described. Cardiac alternans is induced by stepwise decrements (10 ms) in pacing cycle length (CL) but was not measured until 30 seconds after the decrement in rate to assure its stability. 41 CL was decremented until failure to capture the preparation or the development of a ventricular arrhythmia. 29

Data analysis

Isolated myocytes

Action potential duration (APD) was measured at 90% repolarization (APD90). Ca2+ transient parameters were defined as described previously 19 42: Diastolic Ca2+ was defined as cytosolic Ca2+ level just prior to the onset of the Ca2+ transient or just prior to the action potential upstroke in the cases where there was no obvious Ca2+ transient. Amplitude of intracellular Ca2+ transient was calculated from the difference between peak and diastolic Ca2+. The duration of intracellular Ca2+ transient was measured as the onset of the Ca2+ transient to the point of time when the transient decayed 90% of its amplitude. To further quantify the rate of reuptake of intracellular Ca2+, the decay portion of the Ca2+ transient (from 30% to 100% of decline phase) was fit to a single exponential function whose time constant, τ, was used to measure Ca2+ decay.

Action potential duration alternans (APD-ALT) was measured by calculating the difference in action potential duration (APD90) on two consecutive beats, and was defined to be present when APD-ALT exceeded 10 ms as previous described 26. Intracellular Ca2+ transient alternans (Ca-ALT) were measured by calculating the difference in Amplitude on two consecutive beats, and was defined to be present when Ca-ALT exceeded 10% of Ca2+ transient amplitude as described previously 19.

Whole heart

APD alternans (APD-ALT) was defined as the difference in APD between two consecutive beats. 29, 25 The alternans-HR relation was plotted as the magnitude of APD-ALT as a function of HR. A leftward or rightward shift in this relation (i.e. development of alternans at lower or higher HRs) indicates greater or reduced susceptibility to alternans, respectively. The slowest HR that induces alternans was defined as the threshold HR for alternans. 29, 25 26 Activation time, repolarization time and APD were measured from optically recorded action potentials using automated algorithms which have been validated extensively. 25 26 32 Dynamic APD restitution was measured by plotting APD as a function of DI measured during periods of rapid pacing used to promote alternans. 29 Arrhythmia susceptibility was determined using a standardized ramp pacing protocol starting at 300 ms (200 bpm) with stepwise 10 ms decrements in pacing CL until failure of 1/1 capture or the induction of a ventricular arrhythmia. 29 Arrhythmias were defined as a tachyarrhythmia that is sustained for greater than 30 sec after pacing was halted.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data was performed using Sigmastat (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A.). Statistical differences were assessed with Student T-test and Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. When unequal variance was detected during Normality testing the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used. Results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

Efficiency of transgene expression

Figure 1 shows transduction efficiency 72 hours after in-vivo gene transfer. Panel A illustrates a representative example of X-gal stained cross section of guinea pig ventricles following Ad.β-gal gene transfer. The blue stain demonstrates relatively homogeneous gene transfer throughout the epicardium and extending through approximately 2/3 of the transmural wall, leaving the endocardial most myocardium unstained. Panel B illustrates myocytes isolated from the left ventricular free wall of a guinea pig heart transduced with Ad.SERCA2a. Fluorescent image shows the GFP transduction efficiency (green cells) which averaged 29 ± 2%. Panel C demonstrates that SERCA2a (n=3) gene transfer significantly increased SERCA2a protein expression in the left ventricular free wall by 37±7% (p <0.05), compared to control (n=3).

Effect of SERCA2a gene transfer on calcium transient characteristics

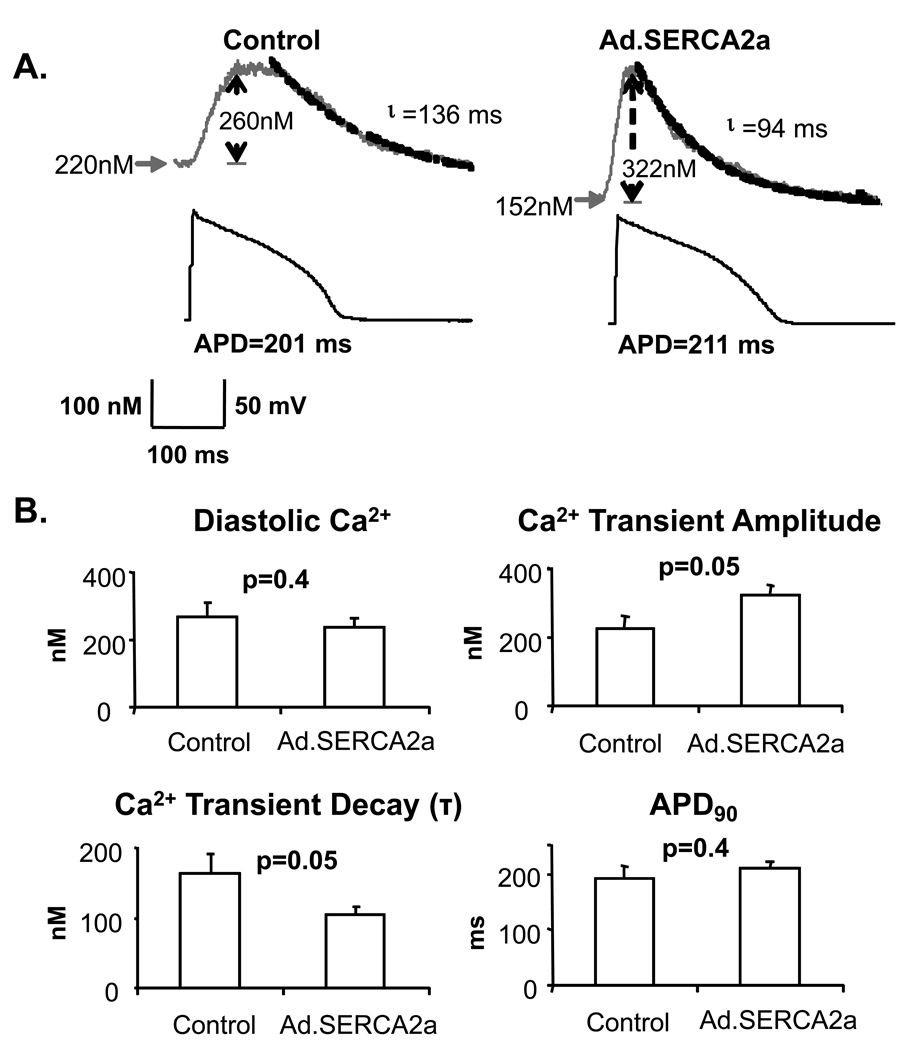

Intracellular Ca2+ transients and action potentials were induced under current clamp conditions at a pacing rate of 150 bpm at 30°C and were compared between isolated control myocytes and myocytes transduced with Ad.SERCA2.GFP 72 hours after in vivo gene transfer. As shown in figure 2 (Panel A), SERCA2a overexpression (right), produced, as expected, accelerated reuptake of cytosolic Ca2+ as measured by the time constant, τ, of Ca2+ transient recovery. Also, Ca2+ transient amplitude was significantly increased (figure 2b) and diastolic Ca2+ was not statistically different between Ad.SERCA2a and control myocytes. Despite differences in Ca2+ transient characteristics, action potential duration was not significantly changed by SERCA2a overexpression (figure 2, panel A). As expected, these data demonstrated that in-vivo transduction of Ad.SERCA2a improved SR Ca2+ reuptake accompanied by larger Ca2+ transients and faster rates of [Ca2+]i decline, confirming that this model of SERCA2a overexpression produces a meaningful effect on SR calcium cycling.

Figure 2. Ca2+ cycling characteristics.

Intracellular Ca transients and action potentials were induced under current clamp conditions at a pacing rate of 150 bpm at 30°C. Panel A: Traces were recorded from a control myocyte (left) and an Ad.SERCA2a myocyte (right). The Ca cycling characteristics in the Ad.SERCA2a myocyte were different from those in the control myocyte as illustrated by faster Ca reuptake (smaller Ca decay time constant (τ), shorter Ca transient duration), and greater Ca release (greater Ca amplitude). However, diastolic [Ca2+] and action potential durations were not statistically different between these cells. Panel B: Summary data from Ad.SERCA2a myocytes (n=6) and control myocytes (n=6) are shown. As compared to control myocytes, Ad.SERCA2a myocytes exhibited markedly faster Ca reuptake (38% faster τ) and greater Ca release (43% larger amplitude).

Effect of SERCA2a gene transfer on susceptibility to cellular alternans in isolated myocytes

APD-ALT and Ca-ALT were measured simultaneously as stimulus rate was progressively increased. Figure 3A shows representative examples of action potential and Ca2+ transient recordings obtained from an Ad.SERCA2a myocyte and a control myocyte. Traces recorded from two consecutive beats are superimposed to illustrate alternans. APD-ALT and Ca-ALT were induced as stimulation rate was increased to 200 bpm in control myocytes. In contrast, alternans could not be initiated even at a pacing rate of 240 bpm in the Ad.SERCA2a myocyte. Data from control myocytes (n=9) and Ad.SERCA2a myocytes (n=11) are summarized in figure 3B. As expected, the magnitude of APD-ALT increased in a rate-dependent fashion. However, in contrast to control myocytes, Ad.SERCA2a myocytes exhibited a significant rightward shift if the APD-ALT – heart rate relationship with greatly attenuated APD-ALT magnitude, indicating induction of marked resistance to APD-ALT with SERCA2a overexpression. The inset of figure 3B shows that under current clamp conditions, the threshold stimulation rate for both APD-ALT and Ca-ALT in control myocytes (n=9) is significantly lower than in Ad.SERCA2a myocytes (n=9).

Figure 3. SERCA2a overexpression suppresses cellular alternans in isolated myocytes.

Panel A: Representative examples of action potential and Ca transient recordings obtained from an Ad.SERCA2a myocyte and control myocyte. Traces recorded from two consecutive beats are superimposed to illustrate alternans. APD-ALT and Ca-ALT were induced as stimulation rate was increased to 200 bpm in the control myocyte, whereas alternans was not initiated until a pacing rate of 375 bpm in the Ad.SERCA2a myocyte. Panel B: SERCA2a overexpression increased alternans threshold and decreased alternans magnitude in isolated myocytes. Plot of pacing rate versus magnitude of APD-ALT from summary data of control myocytes (n=9) and Ad.SERCA2a myocytes (n=11) shows that the magnitude of APD-ALT increased as pacing rate increased, and the magnitude of APD-ALT was consistently greater in control myocytes compared with Ad.SERCA2a myocytes. The inset shows that under current clamp conditions, the threshold stimulation rate for both APD-ALT and Ca-ALT in control myocytes (n=9) is significantly lower than in Ad.SERCA2a myocytes (n=9) (265±17 bpm and 349±22 bpm respectively, p<0.01).

Figure 4 illustrates that SERCA2a overexpression imparts significant resistance to cellular alternans even under constant action potential clamp conditions (i.e. when APD-ALT is prevented). The top tracing is a representation of the action potential clamp protocol (voltage command). In this example, Ca2+ transients recorded under constant action potential clamp conditions at a stimulation rate of 200 bpm are shown in the middle (Ad.SERCA2a myocyte) and in the bottom (control myocyte). At this stimulation rate Ca-ALT was clearly present in control myocytes but not in Ad.SERCA2a myocytes. The 40% increase (p< 0.01) in the heart rate threshold required to induce Ca-ALT under action potential clamp conditions (Figure 4, Panel B), reaffirmed that overexpression of SERCA2a suppressed Ca-ALT as a result of its effects on cellular Ca2+ cycling rather than any indirect effects of the action potential.

Figure 4. SERCA2a overexpression increased alternans threshold even under constant action potential clamp conditions.

Panel A: Ca-ALT occurred under constant action potential clamp conditions. The top trace is action potential clamp protocol (voltage command). In this example, Ca transients recorded under constant action potential clamp conditions at stimulation rate of 200 bpm are shown in the middle (Ad.SERCA2a myocyte) and in the bottom (control myocyte). At this stimulation rate Ca transients alternate in the control myocyte but not in the Ad.SERCA2a myocyte. Panel B: The differences in threshold for Ca-ALT between control (n=12) and Ad.SERCA2a myocytes (n=4) remained even under constant action potential clamp conditions (254±11 bpm and 352±26 bpm respectively, p<0.01).

Effect of SERCA2a gene transfer on susceptibility to cellular alternans in the intact beating heart

APD alternans was measured as pacing rate was progressively increased in the angendorff perfused whole heart. Figure 5 demonstrates that overexpression of SERCA2a increased alternans threshold and decreased alternans magnitude in the whole heart. Plot of pacing rate versus magnitude of APD-ALT from summary data of control (n=8) and Ad.SERCA2a (n=4) transduced hearts shows that the magnitude of APD-ALT increased as pacing rate increased, and the magnitude of APD-ALT was consistently greater in control compared with Ad.SERCA2a hearts. The inset shows that the heart rate threshold for APD-ALT in control hearts is significantly lower than in Ad.SERCA2a hearts (p<0.01). Also, as expected, conduction velocity was not different between Ad.SERCA and control hearts (41.8±6.4 cm/s vs 32.6±2.5 cm/s; p=0.24).

Figure 5. SERCA2a overexpression increased alternans threshold and decreased alternans magnitude in the whole heart.

Plot of pacing rate versus magnitude of APD-ALT from Ad.SERCA2a, control Langendorff-perfused whole hearts shows that the magnitude of APD-ALT increased as pacing rate increased, and the magnitude of APD-ALT was consistently greater in control (n=8) hearts compared with Ad.SERCA2a (n=4) hearts. The inset shows that the threshold pacing rate for APD-ALT in control hearts is significantly lower than Ad.SERCA2a hearts (396±11 bpm and 484±25 bpm respectively, p<0.01).* p≤0.01 Ad.SERCA2a vs control.

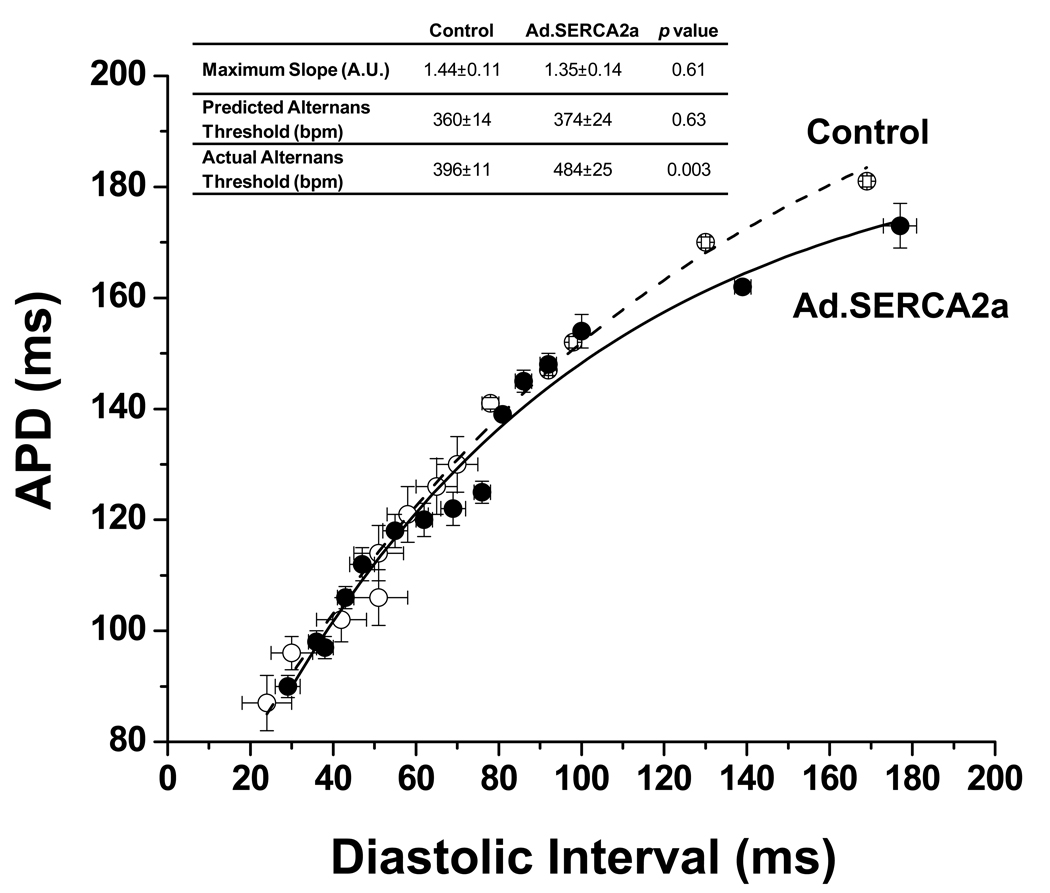

In addition to calcium cycling mechanisms, APD restitution has been implicated in the mechanism of APD-ALT. However, as shown in figure 6, there was no difference in APD restitution (average APD restitution from all experiments are plotted) between controls and Ad.SERCA2a hearts. Moreover, derived metrics of restitution properties such as maximum restitution curve slope and predicted onset heart rate for APD-ALT failed to predict the marked reduction in susceptibility to APD-ALT seen SERCA2a treated hearts.

Figure 6. SERCA2a overexpression does not change dynamic APD restitution in the whole heart.

Plot of mean dynamic APD restitution shows no difference between control and Ad.SERCA2a hearts. The inset shows that the actual threshold pacing rate for alternans was lower in control vs. Ad.SERCA2a hearts yet, there was no significant difference in maximum APD restitution slope or the predicted alternans thresholds.

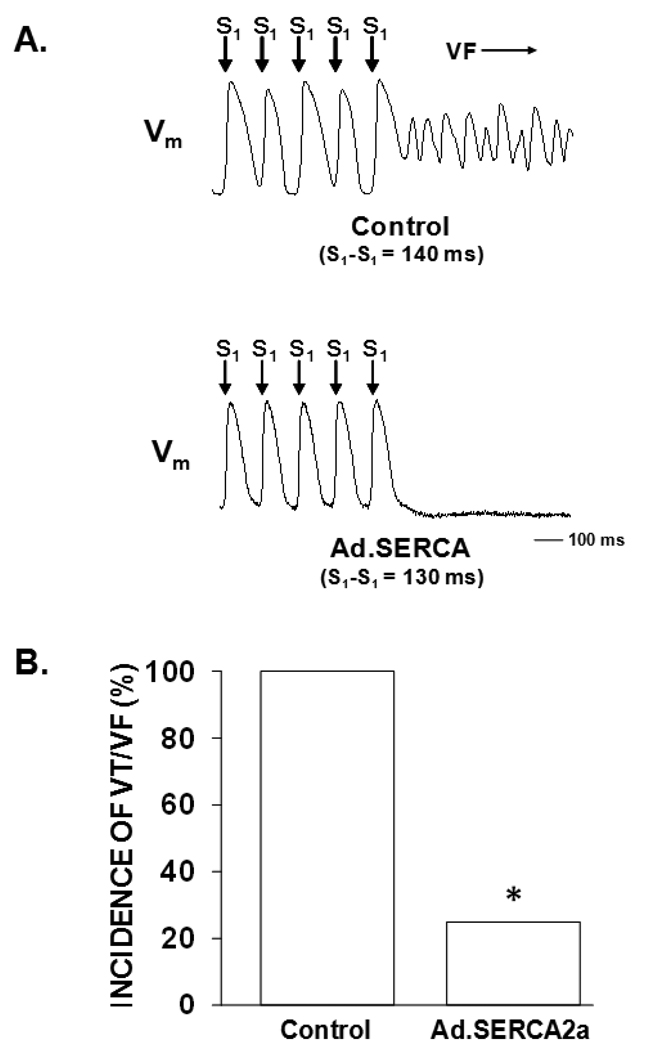

Effect of SERCA2a gene transfer on susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmia

Figure 6A shows representative optical action potential tracings from control and Ad.SERCA2a transduced hearts. In the control heart beat to beat alternation of APD is seen immediately preceding the onset of ventricular fibrillation. This was a consistent finding in all control preparations. Conversely, in the heart transduced with Ad.SERCA2a, the identical stimulation sequence fails to induce cellular alternans or ventricular fibrillation. Figure 6B demonstrates that SERCA2a overexpression reduced susceptibility to alternans-mediated ventricular arrhythmias compared to control (p < 0.05).

In summary, these data show that overexpression of SERCA2a inhibited cellular alternans in both isolated myocytes and the whole heart, suggesting that SERCA2a function plays an important role in the initiation of cellular alternans. Furthermore, SERCA2a overexpression suppresses alternans-mediated ventricular arrhythmias in the intact beating heart.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we 25 and others 30 demonstrated that cellular alternans is a mechanistic precursor to ventricular fibrillation (VF) in the mammalian heart. Presumably in diseased hearts, by lowering the HR threshold for T-wave alternans, vulnerability to VF increases. Therefore, identifying molecular mechanisms which modulate susceptibility to alternans could provide important clues to novel triggers of electrical instability in the heart. The primary findings of this investigation are: (1) overexpression of SERCA2a significantly inhibited cellular alternans in both isolated myocytes and the whole heart, and (2) SERCA2a overexpression suppresses alternans-mediated ventricular arrhythmias in the intact beating heart. These data support our hypotheses that SR calcium cycling plays a causative role in cellular alternans, SERCA2a function specifically plays an important role in the initiation of cellular alternans, and SERCA2a is a potentially novel molecular therapeutic target for the treatment of ventricular arrhythmias.

Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+ Cycling Underlies Mechanism of Cellular Alternans

There are two major hypotheses that have been proposed to explain the development of cellular alternans: 1) the APD restitution hypothesis, largely secondary to alternating sarcolemmal currents and 2) the calcium cycling hypothesis, which states that alternans occurs when HR exceeds the capacity of the myocyte to cycle calcium. Theoretical models suggest that APD alternans occurs when the slope of the APD restitution curve exceeds unity. Moreover, a variety of sarcolemmal currents such as, Ito, 21 ICa, 18 and IKr 22 can exhibit alternating-type activity. Although the restitution hypothesis provides a very useful theoretical framework for understanding the dynamics of APD alternans, there is also considerable experimental evidence which does not support the restitution hypothesis,. 29 9 By using in vivo gene transfer to selectively increase SERCA2a expression, the present study shows that selective enhancement of SR Ca2+ reuptake significantly inhibits both Ca-ALT and Vm-ALT. These finding strongly support a causative role of SR Ca2+ cycling in the mechanism of Vm-ALT. However, it is also possible based on theoretical predictions that SERCA2a overexpression could have altered sarcolemmal ionic currents and these alterations could alter susceptibility to cellular alternans.39 In the present investigation, we distinguished mechanisms arising from intracellular Ca2+ handing versus sarcolemmal ionic currents in isolated myocytes using a non-alternating action potential (AP) clamp. Moreover, since AP clamp is not possible in the intact heart, we compared APD restitution properties of SERCA2a to controls, particularly since APD restitution has been used as an index of the extent to which sarcolemmal ionic currents drive cellular alternans. Interestingly, suppression of Ca-ALT under AP clamp conditions in myocytes (Figure 4) and the lack of a change in APD restitution in whole hearts overexpressing SERCA2a (Figure 6) provides important new evidence that calcium cycling properties can, underlie susceptibility to alternans without any involvement of APD restitution. Also, our data are consistent with previous observations that inhibiting Ca2+ cycling by blocking the RyR, ICa, or by depleting SR Ca2+ stores with caffeine, eradicates Vm-ALT. 11 34 35 Furthermore, the seminal observations of Chudin et al. 3 and our laboratory 42 that Ca-ALT is similarly induced under current-clamp (where Vm-ALT occurs) and voltage-clamp (i.e. where Vm -ALT is prevented) conditions proved that Ca-ALT is not dependent on Vm-ALT, and strongly supported the notion that cellular alternans arises from SR Ca2+ cycling.

Role of SERCA2a in Molecular Mechanism of Cellular Alternans

Despite the importance of Ca-ALT on the development of APD-ALT, the specific Ca2+ cycling proteins responsible for alternans were based primarily on predictions from theoretical models and experimental evidence relying upon associations between impaired SR calcium handling, diminished expression of calcium handling proteins, and susceptibility to cellular alternans. 42; 43 19 The advantage to using in vivo gene transfer targeting a single gene, as in the present study, is the ability to demonstrate a causal relationship between a single protein and the development of cellular alternans. Previously, we suggested that impaired SR Ca2+ reuptake may represent a mechanism to initiate alternans 42. For example, when compared to epicardial myocytes, endocardial myocytes had reduced SERCA2a expression and reduced ability to reuptake cytosolic Ca2+ into the SR. As such, we hypothesized that reduced SERCA2a expression may underlie the increased susceptibility of endocardial myocytes to develop cellular alternans. In the current investigation, we performed in vivo gene transfer using a modified aorto-pulmonary artery cross clamp technique to achieve a 37% increase in SERCA2a. This resulted in improved SR Ca2+ reuptake (i.e. accelerated Ca2+ transient decay and increased Ca2+ transient amplitude) and inhibited cellular alternans in both isolated myocytes and the whole heart. Our results are consistent with the recent observations of Xie et al. 44 that adenoviral-mediated SERCA2a overexpression in cultured rabbit ventricular myocytes suppresses Ca-ALT and the findings that the SERCA2a inhibitor thapsigargin increases susceptibility to cellular alternans 15.

Though this investigation demonstrates with a high degree of specificity that the SERCA2a protein directly affects susceptibility to cellular alternans, these data do not rule out other synergistic or complementary molecular mechanisms. For example, observations from both experimental and theoretical models have demonstrated a steep dependence of SR Ca2+ release on SR Ca2+ load as a mechanism for the development of Ca2+ alternans. 7; 43 Diaz, et al. 7 used an innovative, albeit non-physiological, stimulation protocol to induce Ca-ALT without pharmacological inhibition of RyR (thereby avoiding non-selective drug effects). Ventricular myocytes were repetitively voltage-clamped below the activation voltage for ICa. The resulting weak CICR produced desynchronized RyR release, which dramatically steepened the relationship (feedback gain) between SR Ca2+ content (i.e. luminal Ca2+) and the subsequent SR Ca2+ release. These subcellular conditions highly favored the development of Ca-ALT dynamics that are dependent on beat to beat alternation of SR Ca2+ content. Moreover, instabilities of SR Ca2+ release can also lead to Ca-ALT. For example, using metabolic inhibition in cat atrial and ventricular myocytes to inhibit RyR phosphorylation, Huser et al 13 reported Ca-ALT without beat to beat fluctuations in SR content, suggesting that refractory-like properties of RyR can produce alternating open probabilities of the channel irrespective of SR Ca load. Also, Picht et al. 27 recently demonstrated that beat-to-beat variations in recovery from inactivation of the RyR without variation in SR Ca2+ load can produce Ca-ALT. In contrast, Finally, Lehnart et al. recently demonstrated that Calstabin (FKBP12.6) deficiency increases susceptibility to the development of APD-ALT by destabilizing RyR. 20

Interestingly, in the present study inhibition of cellular alternans in the intact heart occurred despite modest adenoviral transduction efficiency on a cellular scale (29 ± 2% of myocytes). Importantly, our method of virus delivery, produced spatially homogeneous transgene expression in essentially all regions of the heart that were readily accessible for detailed electrophysiological phenotyping using high resolution optical mapping of the intact heart. Moreover, this study demonstrates that complete gene transfer is not required to produce an important electrophysiological phenotype. One explanation for this finding is that electrotonic interactions between neighboring cells via gap junctions act to homogenize membrane potential across cells. For example, reduction in Ca-ALT and therefore, APD-ALT in a cell transduced with Ad.SERCA2a is expected to attenuate APD-ALT in a non-transduced neighboring cell. This is supported by the observation that the magnitude of SERCA2a suppression of cellular alternans in isolated myocytes (Figure 3B) is greater than in whole hearts (Figure 5). These findings have practical clinical implications, suggesting that strategies designed to target SERCA2a gene expression in patients likely does not need to achieve high transduction efficiency for a desirable clinical benefit to be realized. However, it is likely that gene delivery does need to be spatially homogenous throughout the myocardium, as lack of homogeneity could produce electrophysiological heterogeneities that are potentially arrhythmogenic. In fact, the completion of a phase 1/2 clinical trial of myocardial Delivery of AAV1/SERCA2a in Subjects with Advanced Heart Failure has been shown to have an acceptable safety profile in the patients. 14

Enhanced SERCA2a gene expression interrupts a pathway to arrhythmogenesis

The present study demonstrates that targeted overexpression of SERCA2a reduces cellular alternans and susceptibility to inducible arrhythmias in the intact heart. Previously, we demonstrated a mechanistic link between cellular alternans and the genesis of ventricular arrhythmias. 25 Specifically, discordant alternans (i.e. repolarization alternans occurring with opposite phase between neighboring cells) alters the spatial organization of repolarization across the ventricle by markedly amplifying pre-existing heterogeneities of repolarization in the heart; producing a substrate prone to conduction block and reentrant arrhythmogenesis. Therefore, suppression of cellular alternans in the present study decreases the likelihood for amplifying heterogeneity of repolarization, conduction block and thus, ventricular arrhythmias. This observation is consistent with the clinical observation that heart failure patients with a negative T-wave alternans test (the surface ECG representation of cellular alternans) are remarkably resistant to sudden cardiac death. 2 Furthermore, our data are supported by the observations of Del Monte, et al. 6 and Prunier, et al. 28, that overexpression of SERCA2a suppressed ventricular arrhythmias in both rat and porcine models of ischemia – reperfusion (Ca2+ overload). Specifically, ischemia – reperfusion increases diastolic calcium and has been linked to delayed afterdepolarizations and triggered arrhythmias. The authors’ speculate that enhanced SR calcium reuptake with SERCA2a overexpression decreases diastolic Ca2+, thus, decreasing the incidence of DADs and triggered arrhythmias. Additionally, Prunier et al. speculated that one possible mechanism by which SERCA2a overexpression suppressed the development of ventricular arrhythmias in ischemia – reperfusion is by inhibiting cellular alternans. 28

Targeted overexpression of SERCA2a as an anti-arrhythmic therapy has a potential advantage in that this approach does not target sarcolemmal K+ channels; a strategy known to cause QT interval prolongation and proarrhythmiaSERCA2a gene transfer did not prolong repolarization in our studies. However, it is possible that overexpression of SERCA2a could be arrhythmogenic as enhanced SR calcium load could increased susceptibility to spontaneous SR calcium release and DAD-mediated triggered arrhythmias. However, in the present study we saw no evidence of spontaneous arrhythmias or DADs. This may be explained by the modest degree of SERCA2a overexpression seen in this study.

Pathophysiological Implications

Our data have important clinical implications. T-wave alternans has been observed in patients with heart failure and is an important marker of risk for sudden cardiac death (SCD) 24; 31; 38. Moreover, altered calcium cycling is a common observation in heart failure 1 likely caused by reduced SERCA2a expression (impaired SR Ca2+ reuptake), increased phosphorylation of RyR (impaired SR Ca2+ release) and/or altered NCX expression/function. The current investigation suggests that SERCA2a dysfunction can play an important role in modulating susceptibility to cellular alternans, providing a potential link between mechanical and electrical dysfunction in the failing heart. Our data are the first to support a direct causal relationship between SERCA2a function and susceptibility to cellular alternans in the intact heart. Importantly, SERCA2a overexpression has been shown to reverse failure-induced changes in contractility5. Moreover, inhibition of cellular alternans produces a myocardial substrate that is resistant to reentry and fatal arrhythmias. As such, targeted in-vivo gene transfer targeting key SR Ca2+ cycling proteins (i.e. SERCA2a) provides a novel method for understanding the underlying mechanisms for the development of SCD. More importantly, an understanding of these mechanisms combined with improved gene transfer techniques offer potentially a novel strategy for arrhythmia therapy in humans.

T-wave alternans arises from beat to beat alternans of cellular repolarization, is a consistent precursor to ventricular fibrillation in experimental animals, and is a recognized marker of risk for sudden cardiac death (SCD) in patients. However, the molecular basis for cardiac alternans is poorly understood. Previously, we reported an association between deficient expression of SERCA2a, the protein responsible for calcium re-uptake into sarcoplasmic reticulum, and resistance to alternation of calcium transients. In the present study, we demonstrated that targeted in vivo gene transfer of SERCA2a significantly suppresses cellular alternans in the intact heart and voltage-clamped myocytes isolated from these hearts. These findings provided definitive evidence for a primary role of intra-cellular calcium cycling in the mechanism of cardiac alternans. Moreover, SERCA2a gene transfer reduced susceptibility to inducible ventricular arrhythmias in the intact beating heart. Taken together, these data point to a novel molecular target for ameliorating cardiac electrical instability, and suggest possible approaches for genetically engineering hearts that are resistant to ventricular arrhythmias.

Figure 7. SERCA2a overexpression suppresses pacing-induced ventricular arrhythmias.

Panel A: Representative optical action potential tracing from a control heart at a pacing CL of 140 ms demonstrating APD-ALT immediately preceding the onset of ventricular fibrillation. Conversely, in a Ad.SERCA2a heart at an even faster pacing CL(130 ms) there is little to no APD-ALT and the absence of an arrhythmia. Panel B: Using a ramp pacing protocol 8/8 control either VT or VF. In contrast, only 1 of 4 Ad.SERCA2a hearts developed a ventricular arrhythmia (p<0.05). * p<0.05 Ad.SERCA2a vs control.

Acknowledgements

We thank Michelle Jennings for her gracious assistance with data analysis.

Funding Sources

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1-HL54807 (DSR) and Fellowship Awards from the Heart Rhythm Society and NIH National Research Service Award (MJC).

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Hajjar has significant (>$10K) ownership interest in both Celladon and Nanocr.

Journal Subject Codes: [88] Gene therapy; [132] Arrhythmias-basic studies; [136] Calcium cycling/excitation-contraction coupling

REFERENCE LIST

- 1.Bers DM. Altered cardiac myocyte Ca regulation in heart failure. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:380–387. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00019.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloomfield DM, Steinman RC, Namerow PB, Parides M, Davidenko J, Kaufman ES, Shinn T, Curtis A, Fontaine J, Holmes D, Russo A, Tang C, Bigger JT., Jr Microvolt T-wave alternans distinguishes between patients likely and patients not likely to benefit from implanted cardiac defibrillator therapy: a solution to the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial (MADIT) II conundrum. Circulation. 2004;110:1885–1889. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143160.14610.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chudin E, Goldhaber JI, Weiss J, Kogan B. Intracellular Ca2 dynamics and the stability of ventricular tachycardia. Biophysical Journal. 77:2930–2941. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77126-2. 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Del Monte F, Hajjar RJ. Targeting calcium cycling proteins in heart failure through gene transfer. J.Physiol.(Lond.) 2003;546:49–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Monte F, Harding SE, Schmidt U, Matsui T, Kang ZB, Dec W, Gwathmey JK, Rosenzweig A, Hajjar RJ. Restoration of contractile function in isolated cardiomyocytes from failing human hearts by gene transfer of SERCA2a. Circulation. 100:2308–2311. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.23.2308. 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.del Monte F, Lebeche D, Guerrero JL, Tsuji T, Doye AA, Gwathmey JK, Hajjar RJ. Abrogation of ventricular arrhythmias in a model of ischemia and reperfusion by targeting myocardial calcium cycling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5622–5627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305778101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz ME, O'Neill SC, Eisner DA. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content fluctuation is the key to cardiac alternans. Circ Res. 2004;94:650–656. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000119923.64774.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donahue JK, Heldman AW, Fraser H, McDonald AD, Miller JM, Rade JJ, Eschenhagen T, Marbán E. Focal modification of electrical conduction in the heart by viral gene transfer. Nature Med. 2000;6:1395–1398. doi: 10.1038/82214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldhaber JI, Xie LH, Duong T, Motter C, Khuu K, Weiss JN. Action potential duration restitution and alternans in rabbit ventricular myocytes: the key role of intracellular calcium cycling. Circ Res. 2005;96:459–466. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000156891.66893.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirata Y, Kodama I, Iwamura N, Shimizu T, Toyama J, Yamada K. Effects of verapamil on canine Purkinje fibers and ventricular muscle fibers with particular reference to the alternation of action potential duration after a sudden increase in driving rate. Cardiovasc.Res. 1979;13:1–8. doi: 10.1093/cvr/13.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman BF, Suckling EE. Effect of heart rate on cardiac membrane potentials and unipolar electrogram. Am.J.Physiol. 1954;179:123–130. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1954.179.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hüser J, Wang YG, Sheehan KA, Cifuentes F, Lipsius SL, Blatter LA. Functional coupling between glycolysis and excitation-contraction coupling underlies alternans in cat heart cells. J.Physiol.(Lond.) 2000;524:795–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaski BE, Hajjar RJ, Mancini DM, Cappola J, Pauly DF, Greenberg B, Yaroshinsky ARJ, Dittrich HBK, Zsebo KM, Jessup ML. Myocardial Delivery of AAV1/SERCA2a in Subjects with Advanced Heart Failure: A First-In-Human Clinical Trial. Circulation. 2008;118:S2314. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kameyama M, Hirayama Y, Saitoh H, Maruyama M, Atarashi H, Takano T. Possible contribution of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) pump function to electrical and mechanical alternans. J Electrocardiol. 2003;36:125–135. doi: 10.1054/jelc.2003.50021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katra RP, Pruvot E, Laurita KR. Intracellular calcium handling heterogeneities in intact guinea pig hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H648–H656. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00374.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleinfeld M, Stein E, Kossmann C. Electrical alternans with emphasis n recent observations made by means ofsingle-cell electrical recording. Am.Heart J. 1963;65:495–500. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(63)90099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konta T, Ikeda K, Yamaki M, Nakamura K, Honma K, Kubota I, Yasui S. Significance of discordant ST alternans in ventricular fibrillation. Circulation. 1990;82:2185–2189. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.6.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laurita KR, Katra R, Wible B, Wan X, Koo MH. Transmural heterogeneity of calcium handling in canine. Circ Res. 2003;92:668–675. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000062468.25308.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehnart SE, Terrenoire C, Reiken S, Wehrens XH, Song LS, Tillman EJ, Mancarella S, Coromilas J, Lederer WJ, Kass RS, Marks AR. Stabilization of cardiac ryanodine receptor prevents intracellular calcium leak and arrhythmias. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7906–7910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602133103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukas A, Antzelevitch C. Differences in the electrophysiological response of canine ventricular epicardium and endocardium to ischemia: Role of the transient outward current. Circulation. 1993;88:2903–2915. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.6.2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo C, Rudy Y. A model of the ventricular cardiac action potential: Depolarization, repolarization, and their interaction. Circ.Res. 1991;68:1501–1526. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.6.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy CF, Lab MJ, Horner SM, Dick DJ, Harrison FG. Regional electromechanical alternans in anesthetized pig hearts: modulation by mechanoelectric feedback. Am.J.Physiol. 1994;267:H1726–H1735. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.5.H1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pagel PS, Hettrick DA, Kersten JR, Warltier DC. Dexmedetomidine produces similar alterations in the determinants of left ventricular afterload in conscious dogs before and after the development of pacing-induced cardiomyopathy. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:741–748. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199809000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pastore JM, Girouard SD, Laurita KR, Akar FG, Rosenbaum DS. Mechanism linking T-wave alternans to the genesis of cardiac fibrillation. Circulation. 1999;99:1385–1394. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.10.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pastore JM, Rosenbaum DS. Role of structural barriers in the mechanism of alternans-induced reentry. Circ Res. 2000;87:1157–1163. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.12.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Picht E, DeSantiago J, Blatter LA, Bers DM. Cardiac alternans do not rely on diastolic sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content fluctuations. Circ Res. 2006;99:740–748. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000244002.88813.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prunier F, Kawase Y, Gianni D, Scapin C, Danik SB, Ellinor PT, Hajjar RJ, Del Monte F. Prevention of ventricular arrhythmias with sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase pump overexpression in a porcine model of ischemia reperfusion. Circulation. 2008;118:614–624. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.770883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pruvot EJ, Katra RP, Rosenbaum DS, Laurita KR. Role of calcium cycling versus restitution in the mechanism of repolarization alternans. Circ Res. 2004;94:1083–1090. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000125629.72053.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qu Z, Garfinkel A, Chen P, Weiss J. Mechanisms of discordant alternans and induction of reentry in simulated cardiac tissue. Circulation. 2000;102:1664–1670. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.14.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robertson BE, Corry PR, Nye PCG, Kozlowski RZ. Ca2+ and Mg-ATP activated potassium channels from rat pulmonary artery. Pflugers Arch. 1992;421:97–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenbaum DS, Akar FG. The Electrophysiologic Substate for Reentry: Unique Insights From From High-Resolution Optical Mapping With Voltage-Sensitive Dyes. In: Cabo C, Rosenbaum DS, editors. Quantitative Cardiac Electrophysiology. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 2002. pp. 555–582. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenbaum DS, Jackson LE, Smith JM, Garan H, Ruskin JN, Cohen RJ. Electrical alternans and vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias. N.Engl.J.Med. 1994;330:235–241. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401273300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saitoh H, Bailey J, Surawicz B. Alternans of action potential duration after abrupt shortening of cycle length: Differences between dog purkinje and ventricular muscle fibers. Circ.Res. 1988;62:1027–1040. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.5.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saitoh H, Bailey J, Surawicz B. Action potential duration alternans in dog purkinje and ventricular muscle fibers. Circulation. 1989;80:1421–1431. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.5.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saxon LA, Sherman CT, Stevenson WG, Yeatman LA, Wiener I. Ventricular tachycardia after infarction: Sources of coronary blood flow to the infarct zone. Am.Heart J. 1992;124:84–86. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90923-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlotthauer K, Bers DM. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release causes myocyte depolarization - Underlying mechanism and threshold for triggered action potentials. Circ.Res. 2000;87:774–780. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.9.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheu WHH, Jeng C-Y, Shieh S-M, Fuh MMT, Shen DDC, Chen Y-DI, Reaven GM. Insulin resistance and abnormal electrocardiograms in patients with high blood pressure. Am.J.Hypertens. 1992;5:444–448. doi: 10.1093/ajh/5.7.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shiferaw Y, Sato D, Karma A. Coupled dynamics of voltage and calcium in paced cardiac cells. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2005;71:021903. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.021903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Surawicz B, Fisch C. Cardiac alternans: Diverse mechanisms and clinical manifestations. J.Am.Coll.Cardiol. 1992;20:483–499. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker ML, Wan X, Kirsch GE, Rosenbaum DS. Hysteresis effect implicates calcium cycling as a mechanism of repolarization alternans. Circulation. 2003;108:2704–2709. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093276.10885.5B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wan X, Laurita KR, Pruvot E, Rosenbaum DS. Molecular correlates of repolarization alternans in cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss JN, Karma A, Shiferaw Y, Chen PS, Garfinkel A, Qu Z. From pulsus to pulseless: the saga of cardiac alternans. Circ Res. 2006;98:1244–1253. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000224540.97431.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie LH, Sato D, Garfinkel A, Qu Z, Weiss JN. Intracellular Ca alternans: coordinated regulation by sarcoplasmic reticulum release, uptake, and leak. Biophys J. 2008;95:3100–3110. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.130955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]