Abstract

Objective To determine the clinical effectiveness of topical intranasal corticosteroids in children with bilateral otitis media with effusion.

Design Double blind randomised placebo controlled trial.

Setting 76 Medical Research Council General Practice Research Framework practices throughout the United Kingdom, between 2004 and 2007.

Participants 217 children aged 4-11 years who had at least one practice recorded episode of otitis media or a related ear problem in the previous 12 months, and with bilateral otitis media with effusion confirmed by a research nurse using otoscopy plus micro-tympanometry (B/B or B/C2, modified Jerger types).

Intervention Mometasone furoate 50 µg or placebo spray given once daily into each nostril for three months.

Main outcome measures Proportions of children cured of bilateral otitis media with effusion assessed with tympanometry (C1 or A type) at one month (primary end point), three months, and nine months; adverse events; three month diary symptoms.

Results 41% (39/96) of the topical steroid group and 45% (44/98) of the placebo group were cured in one or both ears at one month (difference favouring placebo 4.3% (95% confidence interval −9.3% to 18.1%). Poisson regression was done with adjustment for four pre-specified covariates (clinical severity, P=0.003; atopy, P=0.67; age, P=0.92; season, P=0.71). The adjusted relative risk at one month was 0.97 (95% confidence interval 0.74 to 1.26). At three months, 58% of the topical steroid group and 52% of the placebo group were cured (relative risk 1.23, 0.84 to 1.80). Diary symptoms did not differ between the two groups, and no significant harms were reported.

Conclusions Topical steroids are unlikely to be an effective treatment for otitis media with effusion in general practice. High rates of natural resolution occurred by 1-3 months.

Trial registration Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN38988331; National Research Register NO575123823; MREC 03/11/073.

Introduction

Otitis media with effusion, a collection of fluid behind the ear drum without inflammatory signs,1 is often called “glue ear” when present for six weeks. It is an increasingly common presentation in primary care and is probably the most common reason for surgery in children.2 3 Otitis media with effusion can lead to significant hearing loss, especially when both ears are affected, and has an important impact on children’s lives and development.4 By the age of 4 years, approximately 80% of children will have had an episode of otitis media with effusion, most of which resolve naturally with an average duration of six to 10 weeks; only 10% of episodes last a year or more.5 6 7 However some cases do not resolve quickly and remain a cause for concern, contributing to variable referral rates and surgery (grommets) in between one and five per 1000 children each year.3

A recent review by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence found no proven effective medical treatments for otitis media with effusion that are applicable in primary care, where most children are seen.8 Because the condition might usually be expected to resolve naturally, watchful waiting or active monitoring for three months is now an established clinical recommendation.8 9 10 Active monitoring of such children may be done in primary or secondary care, although questions have been asked as to whether general practitioners have the techniques for active monitoring or whether use of tympanometry in this setting would lead to over-referral.11 During such periods anticipating natural resolution, temporising medical management is often given, including off-licence use of topical intranasal corticosteroids. The reasons for use of topical steroids include preliminary evidence of effectiveness and lack of proven effectiveness of other commonly given treatments such as antibiotics, decongestants, and antihistamines, which are associated with several potential harms and disadvantages,8 some of which are major ones such as antibiotic resistance. Autoinflation is not of proven effectiveness, and achieving cooperation is difficult with the youngest children.12

Topical intranasal corticosteroids have evidence of efficacy from several small clinical trials,13 14 15 as well as theoretical reasons to support further evaluation. Anti-inflammatory effects on the post-nasal space, the peritubal lymphatic tissue, and encroaching adenoids have all been suggested.16 17 Although oral steroids may have some benefit in otitis media with effusion, their use for a chronic relapsing condition of childhood is generally precluded by the possibility of severe idiosyncratic and growth retardation effects.18 19 Thus, although many doctors may be using intranasal corticosteroids in preference to oral steroids for safety reasons,19 20 21 more research is needed to establish their clinical effectiveness when given as an adjunct to active monitoring in an affected cohort of children.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study was a double blind randomised placebo controlled trial of 217 children with a history of otitis media and tympanometrically confirmed bilateral otitis media with effusion. We randomly assigned children to receive either mometasone nasal spray (n=105) or placebo nasal spray (n=112), given for a period of three months to assess likely effectiveness in a health service setting.9 13 We chose mometasone because of its preferred safety profile in children.21 22 Seventy-six practices in the Medical Research Council General Practice Research Framework actively recruited children into the study between 2004 and 2007. Research nurses recruited children aged 4-11 years by using both audit procedures and within practice referrals. Children identified from the audit had either one or more recorded episodes of otitis media in the previous 12 months or histories suggestive of otitis media with effusion, such as speech or language delay or hearing problems. All children identified as clinically “at risk” for otitis media with effusion were then invited for tympanometric screening to diagnose and confirm current bilateral otitis media with effusion.

We excluded children from the study if they had passed tympanometry (that is, had at least one tympanometrically normal ear (A or C1) with which to hear) or had large amounts of wax or uninterpretable tympanograms. We also excluded children at high risk of recurrent disease for whom early referral was indicated (children with cleft palate, Down’s syndrome, primary ciliary dyskinesia, Kartagener’s syndrome, and immunodeficiency states), as well as children with grommets in the drum or perforations, children referred or listed for ear surgery, those for whom developmental concerns about their growth existed, those with frequent or heavy epistaxis, and those with hypersensitivity to mometasone or who had received systemic steroids in the previous three months or were likely to need them (for example, for poorly controlled asthma). We did not include children aged under 4, because pilot work suggested that younger children do not adequately comply with taking nasal sprays.

Procedures

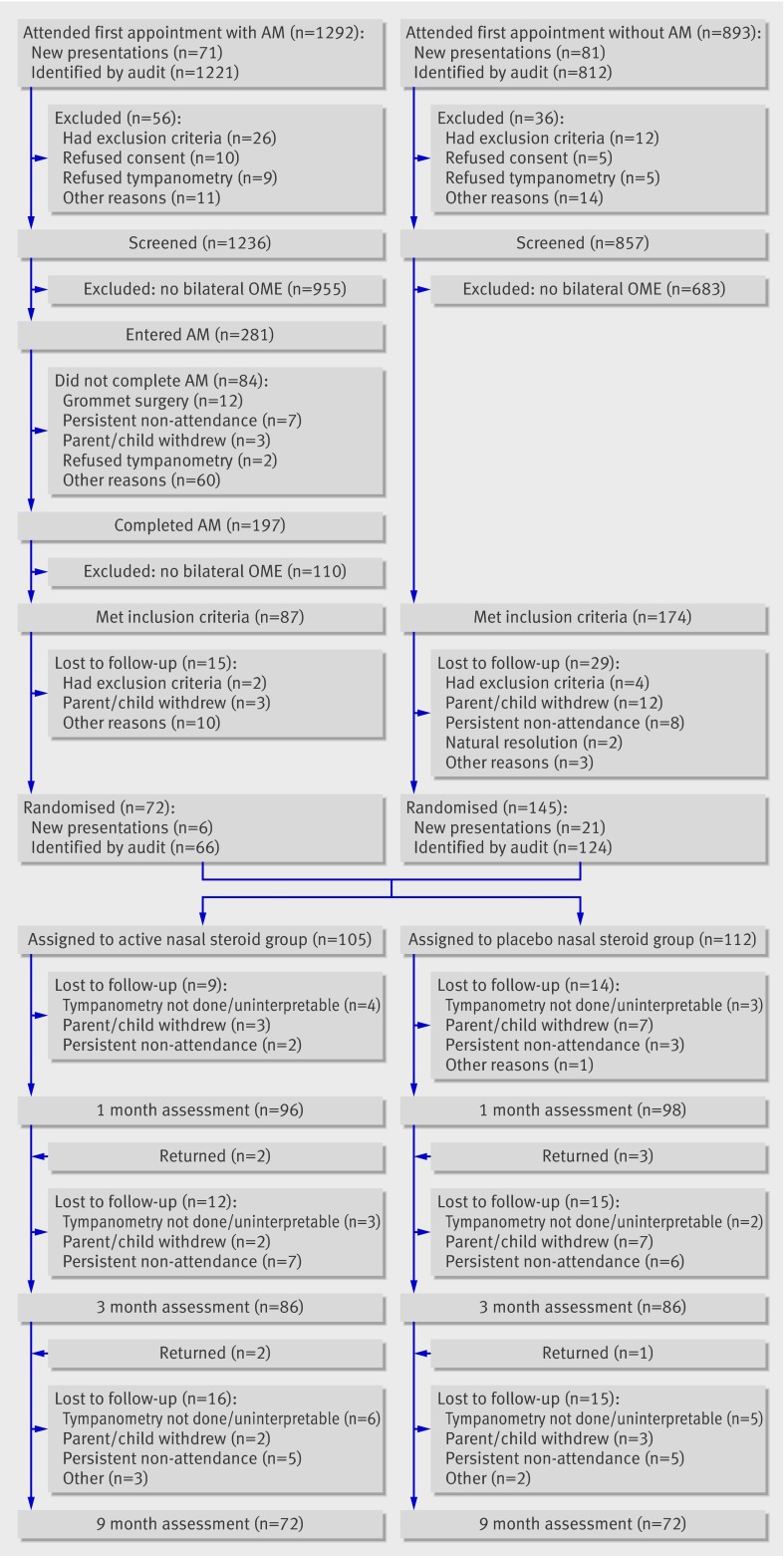

Children were identified through regular monthly audit procedures, and an invitation letter was sent to their guardians. Others were referred directly into the study by the general practitioner, nurse, or health visitor whenever a child presented with suspected otitis media with effusion. A total of 2185 children had full consent given and attended a practice appointment with the research nurse for otoscopy with tympanometric screening, to establish if bilateral otitis media with effusion was present (fig 1). A modified Jerger classification was used to confirm effusion (table 1)23 24; this has been used in a previous study of otitis media with effusion in primary care.25 Children in the first year of the study had a three month period of active monitoring (watchful waiting) if they failed the first screening (B/B or B/C2 types) (n=281) and were invited to be entered into the main study at a second screening only if they failed a second time (n=72). A protocol change agreed and authorised by the data monitoring and ethics committee resulted in the active three month monitoring period being dropped for the remaining study period, to allow children with histories and bilateral tympanometric failure the opportunity to be randomised (50:50) at the first failed screen. This allowed faster recruitment and also took account of the preferences of children’s families and feedback from recruiting nurses.

Fig 1 Trial profile. AM=active monitoring; OME=otitis media with effusion

Table 1.

Tympanometric classification (based on modified Jerger classification)

| Tympanogram | Middle ear pressure (daPa) | Positive predictive value for otitis media with effusion (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| With peaks | Type A | 200 to −100 | Accepted as normal |

| Type C1 | −100 to −199 | ||

| Type C2 | −200 to −399 | 54 | |

| No peak—flat trace | Type B | ≤−400 | 88 |

All research nurses attended at least one full training day with instruction in tympanometric, audiometric, otoscopic, and spray delivery techniques, along with use of questionnaires and the study protocol. Trial support included a tympanometry fax helpline for individual advice on reading and interpreting tympanograms where this was requested or difficult; this also served as ongoing training in the method. Starkey Laboratories provided regular calibration of the hand held MTP10 micro-tympanometers and follow-up advice. Medical Research Council regional nurses also provided additional local and quality control support throughout the study.

At baseline assessments, nurses also carried out sweep audiometry (pass/fail) at a 25dB hearing level at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 KHz (a function of the MTP10). Parents completed an internationally standardised functional measure of health status specifically developed to assess the severity of impact of otitis media with effusion over the preceding three months (OM8-30). This covers global health and eight main domains of impact on the child and family—respiratory symptoms, ear problems, reported hearing difficulties, speech and language, sleep patterns, school prospects, and parents’ quality of life.4 26 Parents were also given a first prospective symptom diary for completion over the following month.

Schering Plough Corporation provided identical nasal sprays with similar look, smell, and taste. These contained either 140 50 μg doses of mometasone furoate or 140 doses of distilled water, with identical excipients (also with a faint rose-scented odour). The nasal sprays were labelled with the patient’s randomisation code number and supplied in identical containers. The code was computer generated externally and block randomised in sets of four, each containing two active and two placebo nasal sprays, and mailed directly by Schering Plough to participating practices. Each patient’s randomised code was placed in an individual sealed envelope and sent as a set to the university; these were also available to participating practices in the event of a suspected serious adverse reaction. No serious adverse events were reported, and all envelopes remained unopened throughout the study.

Parents were given the sprays with instructions for the child to take the spray once into each nostril once a day for one month. The first dose was demonstrated by the nurse, and then the child was placed tilted backwards on the parent’s lap in the head extended position as recommended by the suppliers (to better reach the post-nasal space). Plain instructions were also provided, including those for priming and cleaning of the spray. The child was encouraged to deliver the spray wherever possible. At seven days, parents received a trial support phone call with non-directive questions to estimate adherence and encourage compliance.

At one month after the baseline visit, the sprays were collected for weighing and an additional two month course of nasal spray was provided to be taken in a similar manner, making a three month course in total. Symptom diaries were collected and new ones given for a further two months’ completion.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of children cured of bilateral otitis media with effusion, assessed with tympanometric criteria at one month (proportions of children with at least one ear with an A or C1 type recording), because children with bilateral otitis media with effusion are deemed to be at greater risk of disability than those with good hearing in one ear. We used children rather than ears for the outcome, as ears are not independent variables. Tympanometry provided a more objective measure than parental report.

Other outcome measures included tympanometric cure at three months and nine months after baseline. Few longer term data for non-surgical interventions are available from clinical trials.27 We used diary based symptom and severity scores recorded weekly over three months as estimates of either days affected (for example, days with earache) or severity on Likert-type scales (as used in other studies),28 29 including for adenoidal symptoms. Adverse events were recorded at one and three months, and compliance was measured. Other measures included OM8-30 scores at three and nine months.

Power calculation

The original protocol calculation required 388 children, based on a 0.05 probability of a type 1 error (α) and a 0.2 probability of a type 2 error (β), assuming 21% tympanometric resolution (to type A—a stringent definition of cure) at one month in the topical steroid group versus 10% in the placebo group,13 and assuming a 15% dropout rate. However, the Health Technology Assessment funders agreed to allow for type C1 as cured before the trial started,23 24 25 and we accordingly revised the original power calculation with community prevalence data on A and C1 types.7 We needed 240 children, assuming a 15% dropout rate and a 3% uninterpretable rate for an α of 0.05 and β of 0.2, assuming 28% tympanometric resolution in the topical steroid group and 12% in the placebo group. A 15-16% difference in tympanometric outcomes, based on the one month risk difference in the Tracy study,13 denotes a potentially significant but smaller effect of 7-8% on symptomatic outcomes (the positive predictive value of tympanometry for hearing loss is 0.49).30

The trial under-recruited because of delays with ethics approval, finance restructuring of network recruiting practices, and several interruptions in the sending of batches of placebo supplies. We therefore asked the data monitoring ethics committee, on the recommendation of the trial steering committee after per protocol termination of recruitment (April 2007), whether further funding for an extension of the trial was needed to enable us to recruit to the revised power calculation target. The independent statistician advised against this, as no chance existed that the main findings would be reversed.

Statistical analysis

We did the analysis on an intention to treat basis (that is, by group allocated). We used SPSS version 12 and Stata version 9. We did a sensitivity analysis on the study sample, including and excluding the active monitoring group before randomisation, and found no significant differences for the main tympanometric outcomes at one and three months, so we subsequently combined these populations in the main analyses. We calculated the difference in the main dichotomous treatment outcome, the proportion of children cleared of bilateral effusions at one month, as a rate difference. We used multivariate Poisson regression, with robust error variance,31 to calculate relative risks controlled for pre-specified potential confounders and effect modifiers. These were season (January, February, or March versus the rest of the year), age in months (continuous), atopic history (yes, no), and baseline clinical severity defined as the first principal component of baseline severity markers (frequency of reported ear problems in the previous 12 months, attendances at the surgery for ear problems over 12 months, age of first episode of otitis media, tympanogram readings (B/B versus B/C2), and the OM8-30 adenoidal factor score). We present results as adjusted relative risks with 95% confidence intervals. We tested effect modification by including interactions between randomisation group and age, atopy, and baseline clinical severity in the Poisson regression model and testing for the significance of the interaction. We analysed secondary tympanometric dichotomous outcomes at three and nine months as for the main outcome, by using Poisson regression models with results expressed as relative risks with 95% confidence intervals. We analysed the parent reported symptoms for normality of residuals, and we used non-parametric tests because the data were skewed for all the variables.

Results

The trial profile shows the flow of participants throughout the study period (fig 1). In the active monitoring group, 77.4% (961/1242) of children were excluded by the first tympanometry screen because bilateral otitis media with effusion was not confirmed and 55% (109/197) were excluded after three months because bilateral otitis media with effusion had not persisted. In those without active monitoring, 79.7% (683/857) were excluded because bilateral otitis media with effusion was not confirmed. In all, 261 children met the study entry criteria and 217 were randomised—72 with previous active monitoring and 174 without. Table 2 shows that potential confounders were equally distributed between the groups, but with slightly more boys in the placebo group (56% v 44%), confirming that randomisation was effective overall. The level of retention was high—93% (201) at one month, 84% (182) at three months, and 73% (158) at nine months. At one month, 7% (16) of children were lost to follow-up but a further 3% (7) had missing tympanometric data, were uncooperative, or had uninterpretable tympanograms. We assumed that all missing data were missing at random and censored them in the analysis (without imputation).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of randomised children. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Active treatment group (n=105) | Placebo group (n=112) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD, range) age (months) | 73.3 (20.2, 49-129) | 72.1 (18.6, 48-125) |

| Male sex | 52 (50) | 63 (56) |

| Season randomised: | ||

| January-March | 42 (40) | 44 (39) |

| April-December | 63 (60) | 68 (61) |

| Daycare | 101/104 (97) | 105/106 (99) |

| Smoking in household | 9/104 (9) | 10/106 (9) |

| Atopy | 35 (33) | 33 (29) |

| Ethnicity*: | (n=68) | (n=69) |

| White | 66 (97) | 66 (96) |

| Bangledeshi/Indian | 0 (0) | 2 (3) |

| Mixed | 2 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Age at first ear infection: | (n=102) | (n=106) |

| Not had one | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| <12 months | 27 (26) | 31 (29) |

| 12-24 months | 44 (43) | 40 (38) |

| 2-3 years | 14 (14) | 16 (15) |

| ≥3 years | 17 (17) | 18 (17) |

| Mean (SD, range) frequency of GP surgery episodes for ear related problems in previous 12 months | 2.29 (1.96, 0-14) (n=103) | 2.13 (1.53, 0-9) (n=106) |

| Parent reported frequency of ear infections in previous 12 months: | (n=104) | (n=106) |

| 0 | 6 (6) | 6 (6) |

| 1-2 | 35 (34) | 50 (47) |

| 3-4 | 41 (39) | 33 (31) |

| ≥5 | 22 (21) | 17 (16) |

| Grommets inserted >12 months before randomisation | 0/95 (0) | 2/102 (2) |

| Adenoidectomy before randomisation | 1/95 (1) | 2/102 (2) |

| Highest qualification achieved by parent; second parent*: | (n=66; n=59) | (n=70; n=54) |

| School to 16, no qualifications | 9 (14); 8 (14) | 5 (7); 8 (15) |

| School to 16, GCSEs/O levels | 18 (27); 26 (44) | 23 (33); 19 (35) |

| Sixth form school or college, A levels, ND | 15 (23); 7 (12) | 12 (17); 8 (15) |

| Highers, Scotvec, or NVQ | 11 (17); 8 (14) | 16 (23); 6 (11) |

| University degree | 10 (15); 4 (7) | 10 (14); 5 (9) |

| Professional or postgraduate degree | 3 (5); 6 (10) | 4 (6); 8 (15) |

*Data collected only after active monitoring removed from protocol.

Main findings

At one month, the proportion of children who were cleared of effusions in at least one ear was 41% (39/96) in the topical steroid group and 45% (44/98) in the placebo group. The risk difference in favour of placebo was 4.3% (95% confidence interval −9.3 to 18.1) (table 3). The relative risk was 0.91 (95% confidence interval 0.65 to 1.25). We analysed the effect of the different recruitment cohorts, active monitoring versus no active monitoring, at each outcome time point (one, three, and nine months) by using the χ2 test, and it was non-significant. We did Poisson regression analysis on four covariates: age as a continuous variable (P=0.92), season (P=0.71), atopy (P=0.67), and clinical severity (P=0.003). The relative risk adjusted for these four covariates at one month for the main outcome was 0.97 (0.74 to 1.26) (table 3). Secondary analysis at three months showed that 58% of the topical steroid group and 52% of the placebo group had resolved (adjusted relative risk 1.23, 0.84 to 1.80). At nine months, 56% of the topical steroid group remained clear in at least one ear, but 65% of the placebo group remained clear (adjusted relative risk 0.90, 0.58 to 1.41, favouring placebo). The interactions between treatment group and age (P=0.57), treatment group and atopy (P=0.24), and treatment group and clinical severity (P=0.89) were non-significant, showing that the effect of treatment group was not significantly affected by age, atopy, or clinical severity.

Table 3.

Children cured of otitis media with effusion according to tympanometric criteria (that is, proportions of children with either A or C1 tympanogram in at least one ear)

| Time of cure | No (%) | Risk difference (%) (95% CI) | Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | Placebo | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value | |||

| 1 month | 39/96 (41) | 44/98 (45) | 4.3 (–9.3 to 18.1) | 0.91 (0.65 to 1.25) | 0.55 | 0.97 (0.74 to 1.26) | 0.81 | |

| 3 months | 50/86 (58) | 45/86 (52) | –5.8 (–20.2 to 8.9) | 1.11 (0.85 to1.46) | 0.44 | 1.23 (0.84 to 1.80) | 0.29 | |

| 9 months | 40/72 (56) | 47/72 (65) | 9.7 (–5.5 to 25.6) | 0.85 (0.65 to 1.11) | 0.23 | 0.90 (0.58 to 1.41) | 0.65 | |

Overall, we found a low risk of individual children not being cured—57% at one month, decreasing by a further 60% at three months and 60% at nine months (proportion of those remaining unresolved throughout 0.18, 0.13 to 0.26) (fig 2). The rate of referral to ear, nose, and throat specialists was low at 15/102 (15%) for the active group and 17/112 (15%) for the placebo group at nine months; 60% of these referrals were deemed appropriate according to suggested Medical Research Council criteria.

Fig 2 Natural history of bilateral otitis media with effusion in a primary care population

Adverse events, although relatively minor, included cough, dry throat, epistaxis, and nasal stinging (table 4). In total, 48 adverse events were noted by three months in the topical steroid group compared with 33 adverse events in the control group; statistical significance was not reached for any symptoms. The reported hearing difficulty (P=0.08) and days with otalgia (P=0.46) from the diaries at three months did not differ significantly between the groups at three months. Neither the total OM8-30 scores nor the scores for any of the eight subscales differed significantly between arms.

Table 4.

Adverse effects experienced while taking active or placebo spray as reported at one and three month assessments

| Adverse effect | No (%) | P value | Relative risk (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | Placebo | |||

| One month assessment | ||||

| Stinging in nose | 9/96 (9) | 10/102 (10) | 0.92 | 0.96 (0.41 to 2.25) |

| Nose bleed | 8/97 (8) | 7/101 (7) | 0.73 | 1.19 (0.45 to 3.16) |

| Dry throat | 13/96 (14) | 14/102 (14) | 1 | 0.99 (0.49 to 1.99) |

| Cough | 23/97 (24) | 19/102 (19) | 0.38 | 1.27 (0.74 to 2.19) |

| Three month assessment | ||||

| Stinging in nose | 9/85 (11) | 9/85 (11) | 1 | 1.00 (0.42 to 2.40) |

| Nose bleed | 10/86 (12) | 6/84 (7) | 0.32 | 1.63 (0.62 to 4.28) |

| Dry throat | 10/85 (12) | 7/83 (8) | 0.47 | 1.40 (0.56 to 3.49) |

| Cough | 19/86 (22) | 11/83 (13) | 0.13 | 1.67 (0.85 to 3.29) |

Pass/fail results on sweep audiometry (fail at two or more frequencies at 25 dB hearing level in the better ear) did not differ between the groups: 63% (52/83) of treated children versus 58% (47/81) of those in the placebo group failed at three months, as did 59% (44/74) versus 51% (34/67) at nine months.

We evaluated concealment in children and parents (guardians), and prediction of the correct group was no better than chance. More than 80% of parents (guardians) in the placebo group thought their children were receiving the active treatment. Reported adherence was very good or excellent in 95/99 (96%) children in the topical steroid group and 93/103 (90%) in the placebo group at one month and in 79/90 (88%) and 78/89 (88%) at three months. Analysis of adherence by age group showed a non-significant difference for the main outcome at one and three months (Fisher’s test 0.04; χ2 test for trend P=0.40).

Discussion

The main findings show that three months’ use of topical intranasal corticosteroids in 4-11 year old children seems to be no better than placebo in improving clearance of effusions of otitis media at one, three, and nine months, or in improving important symptom related outcomes. This is an important and under-researched area of child health, as evidence for the use of promising non-surgical interventions for otitis media with effusion is lacking. Otitis media with effusion is a common chronic problem seen in primary care, for which no effective treatment exists in this setting and which often leads to referral and surgery.

This UK-wide primary care study is the largest double blind randomised placebo controlled trial of topical intranasal corticosteroids in children with otitis media with effusion from any health setting; it is larger than the only previous randomised controlled trial from primary care that evaluated antibiotics.25 Follow-up rates were high, and we did not impute missing results (which would provide even more conservative findings than this analysis so would not alter the inferences). The results should thus be both relevant and generalisable to most children seen in the NHS.

This study used an objective outcome that evaluated efficacy in clearing bilateral effusions at one month. Although several small studies have suggested efficacy for topical nasal steroids, and they are often used off-licence for this condition, efficacy has not been convincingly demonstrated in the literature.18 The risk difference (measured in children rather than ears) was 4.3% (95% confidence interval −9.3 to 18.1) in favour of placebo. The main findings show that the adjusted relative risks were less than 1 at one and nine months, indicating that placebo did better in both the short and longer term.

This study has shown that when an active monitoring scheme (sometimes called watchful waiting) is used in primary care, almost half of children will spontaneously clear the fluid from at least one of their ears by as soon as one month, and thus considerably reduce their risk of disability.5 6 7

Possible reasons for negative trial

One possible reason for a negative result is that the primary care sample was not sufficiently severe to show any benefit of treatment. However, we selected the sample of children on the basis of episodes of typical symptoms that present in the NHS; children had been seen on average twice in the preceding 12 months for otitis media or an ear related problem (reflecting prevalence).2 Cases were further confirmed by objective tympanometric criteria, with a high positive predictive value of 88% of a B tympanogram for an actual effusion. Children had to have either B/B or B/C2 to enter the trial (the tympanometrically worst 5% of the general population of children).7 When we added even stricter criteria for persistence—a fail on two occasions (B/B, B/C2) three months apart before randomisation—a sensitivity analysis on the more persistent sample showed no difference on the tympanometric outcomes at one and three months. The total mean adjusted OM8-30 scores across symptom/impact domains showed baseline clinical severity to be high. Compared with the as yet unpublished secondary care Trial of Alternative Regimens for Glue Ear Treatment (TARGET), our sample was 0.24 SD less severe than children seen in UK ear, nose, and throat departments on the developmental subscale (P=0.014) and worse on the physical health subscale (non-significant). When the standard deviation for the difference between the UK (TARGET) secondary care sample and scores from our sample was adjusted by multilevel modelling, the difference of 0.04 SD was not significant. The mean total score for our sample was also higher than that for most Eurotitis secondary care samples (M Haggard (MRC OM study group), personal communication, 2008).32 Although secondary care populations might thus be speculated to gain some benefit because of spectrum bias,14 this seems unlikely, and risk groups such as those with atopic features were not a predictor of outcome in this trial.

If adherence had been poor in the study, this might have explained the negative findings. However, the trained research nurses delivered the quality controlled intervention and the reported adherence was very high—over 90% at one month and approaching 90% even by three months, which was higher than anticipated (and supported by data on bottle weights).33 Although the possibility that suboptimal adherence contributed to these negative findings remains, adherence in this trial setting is likely to be higher than that in routine clinical practice.

The trial may not have been sufficiently powered (type 2 error), considering that we found an unexpectedly high event rate of 45% in the control group. This meant that the study had the power to detect only a 20% difference from 45% to 25%. However, considering the effect size observed, a maximum difference for any benefit is given by the 95% confidence limit at 9.3%. One could argue that this is important clinically and that some children might benefit. However, clinical interpretation of these findings suggests that in terms of important symptoms such as hearing loss, this maximally beneficial difference on tympanometry is approximately halved (to 4.6%) because tympanometry only weakly predicts hearing level.30 We found no effects on any of the multiple continuous outcome measures we analysed, such as days with symptoms, although histories lack sensitivity for detecting hearing loss.34

The tympanometric main outcome was a robust objective measure applicable with appropriate training and support in primary care. It added rigour for a condition for which diagnosis based on history and otoscopy alone has a fairly low sensitivity and specificity,8 as is the case in a primary care sample where routine over-prescribing is more likely.2 Few UK general practitioners are skilled in pneumatic otoscopy, but tympanometry is feasible, gives a high positive predictive value, and is useful for assessing natural resolution or response to treatment.

Hearing level as an objective outcome, although clinically important, is problematic for a primary care study because the gold standard of pure tone audiometry is very difficult to do reliably in primary care practices, particularly in younger children and where usual high levels of background noise invalidate the findings. For these reasons, we did not consider it to be reliable as a study outcome.

Conclusions

The main findings favouring placebo at one and nine months provide evidence that topical intranasal corticosteroids are not likely to be an effective means of treating children with bilateral otitis media with effusion. The study has demonstrated the feasibility of active monitoring in general practice, with particularly high natural resolution rates occurring after as little as one month of follow-up.

What is already known on this topic

Otitis media with effusion is the most common chronic condition of childhood and can cause hearing, speech, behavioural, and developmental problems

It is the most common reason for surgery in children in the UK

No non-surgical interventions of proven efficacy exist

What this study adds

Topical intranasal corticosteroids are not likely to be an effective treatment for otitis media with effusion

Active monitoring (watchful waiting) in primary care is feasible and acceptable to children and families and is associated with high natural cure rates and low referral rates

Tympanometry can help management by identifying, selecting, and monitoring children with relevant histories of otitis media

We acknowledge sponsorship from the University of Southampton. We thank the Medical Research Council General Practice Research Framework practices, the regional nurses for the field work, and especially the participating children and families. We also thank Helen Spencer for aspects of the OM8-30 analysis, Peter Robb for early advice on the project, Starkey Laboratories for tympanometry support, and Schering Plough for providing the drug and placebo and assisting with the randomisation.

Contributors: IW was the chief investigator. SBenge was the trial manager and was responsible for data management. SBarton was responsible for the statistical analysis. SP contributed to the study design and writing the manuscript. LL and NF contributed to the fieldwork design and writing the manuscript. MH contributed to the study design and OM8-30 analysis. PL contributed to the study design and methods and to writing the manuscript. IW is the guarantor.

Funding: Health Technology Assessment Programme. The views herein expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The study received ethics approval from the Metropolitan Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee and 60 local research ethics committees and research governance approval from 76 primary care trusts.

Data sharing: No additional data available (but see also full report33).

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;340:b4984

References

- 1.Stool SE, Berg AO, Berman S, Carney CJ, Cooley JR, Culpepper L, et al. Otitis media with effusion in children. 1994. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=hsarchive&part=A34095.

- 2.Williamson I, Benge S, Mullee M, Little P. Consultations for middle ear disease, antibiotic prescribing and risk factors for re-attendance: a case linked cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:170-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health. Trends in children’s surgery 1994-2005: evidence from hospital episode statistics data. Stationery Office, 2007 (available at www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsStatistics/DH_066322).

- 4.Haggard MP, Smith SC. Impact of otitis media on child quality of life. In: Rosenfeld RM, Bluestone CD, eds. Evidence based otitis media. BC Decker, 1999:375-98.

- 5.Zielhuis GA, Rach GH, Broek PV. Screening for otitis media with effusion in preschool children. Lancet 1989;1:311-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogan SC, Stratford KJ, Moore DR. Duration and recurrence of otitis media with effusion in children from birth to 3 years: prospective study using monthly otoscopy and tympanometry. BMJ 1997;314:350-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williamson IG, Dunleavey J, Bain J, Robinson D. The natural history of otitis media with effusion—a three year study of the incidence and prevalence of abnormal tympanograms in four south west infant and first schools. J Laryngol Otol 1994;108:930-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Surgical management of otitis media with effusion in children. NICE, 2008 (available at www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG60NICEguideline.pdf).

- 9.Browning GG. Watchful waiting in childhood otitis media with effusion. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 2001;26:263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lous J, Burton M, Felding J, Ovesen T, Rovers MM, Williamson I. Grommets (ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(1):CD001801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maw AR. Using tympanometry to detect glue ear in general practice. BMJ 1992;304:67-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perera R, Haynes J, Glasziou P, Heneghan CJ. Autoinflation for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD006285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tracy JM, Demain JG, Hoffman KM, Goetz DW. Intranasal beclomethasone as an adjunct to treatment of chronic middle ear effusion. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1998;80:198-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fokkens WJ, Scadding GK. Perennial rhinitis in the under 4s: a difficult problem to treat safely and effectively? A comparison of intranasal fluticasone proprionate and ketotifen in the treatment of 2-4 year old children with perennial rhinitis. Ped Allergy Immunol 2004;15:261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cengel S, Akyol MU. The role of topical nasal steroids in the treatment of children with otitis media with effusion and/or adenoid hypertrophy. Int J Ped Otorhinolaryngol 2006;70:639-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yaman H, Ozturk K, Uyar Y, Gurbilek M. Effectiveness of corticosteroids in otitis media with effusion: an experimental study. J Laryngol Otol 2008;122:25-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenfeld RM, Mandel EM, Bluestone CD. Systemic steroids for otitis media with effusion in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991;117:984-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butler CC, Van der Voort JH. Oral or topical nasal steroids for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(3):CD001935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williamson I. Otitis media with effusion. Clin Evid 2006;15:814-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barek PJ, Bergman DA, Ducharme F. Beclomethasone for asthma in children: effects on linear growth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1999;(3):CD001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shenkel EJ, Skoner DP, Bronsky EA, Miller D, Pearlman DS, Rooklin A, et al. Absence of growth retardation in children with perennial allergic rhinitis after one year of treatment with mometasone furoate aqueous nasal spray. Pediatrics 2000;105:e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skoner DP, Rachelefsky GS, Meltzer EO, Chervinsky P, Morris RM, Seltzer JM, et al. Detection of growth suppression in children during treatment with intranasal beclomethasone diproprionate. Pediatrics 2000;105:e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiellau-Nikolajsen M. Epidemiology of secretory otitis media; a descriptive cohort study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1983;92:172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jerger J. Clinical experience with impedance audiometry. Arch Otolaryngol 1970;92:311-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Balen FAM, de Melker RA, Touw-Otten FW. Double blind randomized trial of co-amoxiclav versus placebo for persistent otitis media with effusion in general practice. Lancet 1996;348:713-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haggard M, Spencer H, Williamson I, Benge SE.Caseloads in otitis media: effects of season and selective referral to secondary care [abstract 5SOP1]. 8th ESPO International Conference, Budapest, June 2008.

- 27.Bisset A. Treatment of glue ear in general practice. Lancet 1996;349:134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Little P, Gould C, Williamson I, Moore M, Warner G, Dunleavey J. Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of two prescribing strategies for childhood acute otitis media. BMJ 2001;322:336-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williamson I, Rumsby K, Benge S, Moore M, Smith P, Cross M, et al. Antibiotics and topical nasal steroid for treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis: a double blind randomized placebo controlled trial. JAMA 2007;298:2487-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dempster JH, Mackenzie K. Tympanometry and the detection of hearing impairment associated with otitis media with effusion. Clin Otolaryngol 1991;16:157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mendes Leal M, Marques P, Vaz R, Sprately J, Haggard M, Spencer H. Factors in severity of OME seen in secondary care [abstract 5SOP4]. 8th ESPO International Conference, Budapest, June 2008.

- 33.Williamson I, Benge S, Barton S, Petrou S, Letley L, Fasey N, et al. A double-blind randomised placebo controlled trial of topical intra-nasal corticosteroids in 4- to 11-year old children with persistent bilateral otitis media with effusion in primary care. Health Technol Assess 2009;13(37):1-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nondahl DM, Cruickshanks KJ, Wiley TL, Tweed TS, Klein R, Klein BE. Accuracy of self-reported hearing loss. Audiology 1998;37:295-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]