Abstract

AIM: To compare survival between bile duct segmental resection (BDSR) and pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) for treating distal bile duct cancers.

METHODS: Retrospective analysis was conducted for 45 patients in a BDSR group and for 149 patients in a PD group.

RESULTS: The T-stage (P < 0.001), lymph node invasion (P = 0.010) and tumor differentiation (P = 0.005) were significant prognostic factors in the BDSR group. The 3- and 5-year overall survival rates for the BDSR group and PD group were 51.7% and 36.6%, respectively and 46.0% and 38.1%, respectively (P = 0.099). The BDSR group and PD group did not show any significant difference in survival when this was adjusted for the TNM stage. The 3- and 5-year survival rates were: stage Ia [BDSR (100.0% and 100.0%) vs PD (76.9% and 68.4%) (P = 0.226)]; stage Ib [BDSR (55.8% and 32.6%) vs PD (59.3% and 59.3%) (P = 0.942)]; stage IIb [BDSR (19.2% and 19.2%) vs PD (31.9% and 14.2%) (P = 0.669)].

CONCLUSION: BDSR can be justified as an alternative radical operation for patients with middle bile duct in selected patients with no adjacent organ invasion and resection margin is negative.

Keywords: Bile duct cancer, Segmental resection, Pancreaticoduodenectomy

INTRODUCTION

Extrahepatic bile duct cancer can be classified into hilar, proximal, middle and distal bile duct cancer (DBD) according to the portion of the involved bile duct. Hilar and proximal bile duct cancers (PBD-1) are classified into 5 types as described by Bismuth and Corlette[1]. This classification of extrahepatic bile duct cancers is due to the differences in the operative methods that are employed for cancers involving different portions of the bile duct. According to numerous reports, most surgeons consider bile duct resection with liver parenchyma resection to be the standard operation for hilar cholangiocarcinoma[2-4]. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is performed for DBD. Bile duct cancers confined to the middle bile duct (MBD) are rare because bile duct cancers have a tendency to spread along the bile duct wall. This is the reason why PD is usually undertaken for treating most MBD cancers. Yet there is still debate as to the appropriate operative procedure for the bile duct cancers that do not extend above the confluence or below the upper border of the pancreas. PD or bile duct segmental resection (BDSR) is performed at the surgeon’s discretion. Clinicopathological studies on hilar and distal cholangiocarcinomas have been done by many authors[2-11], and the results of BDSR for MBD have been reported, but most of these studies involved a very limited number of cases, and the number of cases is not enough to justify BDSR as a standard treatment.

In the current study, a clinical review of patients who received BDSR (negative resection margins) with lymph node (LN) dissection for the Bismuth type I PBD-1 and also the patients with MBD was performed. We compared survival between BDSR group and PD for treating DBD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between November 1995 and May 2007, 379 patients underwent surgical procedures that were performed for treating extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas at Samsung Medical Center. One hundred nine patients who underwent concomitant liver resection and 76 patients who underwent palliative procedures were excluded, and only the cases with bile duct adenocarcinomas that had been confirmed by pathologic assessment were included. There were 45 patients who underwent BDSR for PBD-1 or MBD (BDSR group), and 149 patients who underwent PD for DBD (PD group). A retrospective analysis was performed via a review of the medical records and by conducting telephone interviews. The clinicopathologic factors of the BDSR group that we analyzed were age, gender, the preoperative carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) level, serum bilirubin levels both at the time of admission and prior to surgery, preoperative biliary drainage, transfusion, the site of cancer, the extent of LN dissection [D1 (LN #12) or D2 (LN #12, #8, #13)], tumor size, histologic differentiation, TNM stage, LN metastasis and perineural invasion. To find the exact location of the tumor, ERCP or PTC and recently MRCP was done before surgery. Before surgery, biliary and GB CT scans were performed to see if there was invasion to adjacent tissues or organs. Angiography was used to detect any evidence of vascular invasion, but after 1999, we used the CT scan to rule out any vascular invasion. In the BDSR group, all patients underwent frozen section for both bile duct resection margins and to be confirmed as free from carcinoma intraoperatively and on permanent pathology. The tumor stage was based on the 6th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer cancer staging[12]. All patients were monitored at 6 mo intervals by measuring CA19-9 levels and performing a CT scan for 3 years and were checked annually at 6 mo intervals. Four patients (8.8%) in the BDSR group were lost to follow up.

Statistical analysis

Survival of the BDSR and the PD groups was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to analyze differences. Only variables that were statistically significant on univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis, which was performed using a Cox proportional hazard regression model. Survival analysis of the PD group was done by the Kaplan-Meier method and comparison of survival between the BDSR group and the PD group was done by log-rank tests. χ2 tests and a Mann-Whitney U-test were used for comparing the postoperative complications and the length of the hospital stay between the 2 groups. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of the groups of patients who underwent BDSR for PBD-1 and MBD

Clinical characteristics of the groups of patients who underwent BDSR for PBD-1 and MBD are shown in Table 1. There were 45 patients who underwent BDSR for PBD-1 or MBD. There were 30 (66.7%) males and 15 (33.3%) females. The median age of the patients was 65 years (range: 37-76 years). BDSR with LN dissection and hepaticojejunostomy was done for all these patients, with negative proximal and distal bile duct resection margins being achieved in all 45 patients. The complications arising during the immediate postoperative period (within 1 mo) were analyzed. There were 9 patients with wound infections, pancreatitis, bile leakage and delayed gastric emptying. Dissection of the superior border of the pancreas was done due to the close distal resection margin in all 3 patients who showed postoperative pancreatitis. Of 45 patients, D2 LN dissection (LN #12, #8, #13) was done in 37 (82.2%) patients and D1 dissection (LN #12) was done in 8 (17.8%) patients. LN metastasis was present in 13 (28.8%) patients and perineural invasion was present in 32 (71.1%) patients. Nine (20%) patients had T1 lesions, 33 (73.3%) patients had T2 lesions and 3 (6.7%) patients had T3 lesions with invasion into the gallbladder without liver or pancreas invasion. Nine (20%) patients were stage Ia (T1N0M0), 23 (51.1%) patients were stage Ib (T2N0M0), and 13 (28.9%) patients were stage IIb (T1-3N1M0). There were no stage IIa (T3N0M0) patients. The median follow-up period was 25 mo (range: 4-104 mo) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of the predictors for survival of the 45 patients who underwent radical BDSR for PBD-1 or MBD disease

| Characteristic | Number of patients | Median survival time (mo) |

Survival rate (%) |

P-value | |

| 3-yr | 5-yr | ||||

| Overall | 45 | 25 | 51.7 | 36.6 | |

| Age (yr) | 0.466 | ||||

| ≤ 65 | 25 | 42 | 56.4 | 38.7 | |

| > 65 | 20 | 33 | 45.5 | 34.1 | |

| Gender | 0.314 | ||||

| Male | 30 | 35 | 47 | 28.2 | |

| Female | 15 | 42 | 58.2 | 48.5 | |

| CA19-9 (U/mL) | 0.519 | ||||

| ≤ 35 | 19 | 42 | 51.6 | 25.8 | |

| > 35 | 19 | 55 | 61.5 | 49.2 | |

| No data | 7 | ||||

| Bilirubin at admission (mg/dL) | 0.368 | ||||

| ≤ 1.6 | 11 | NR | 53.3 | 53.3 | |

| > 1.6 | 34 | 42 | 50.5 | 34.1 | |

| Bilirubin at operation (mg/dL) | 0.149 | ||||

| ≤ 1.6 | 17 | 55 | 65.5 | 43.6 | |

| > 1.6 | 28 | 29 | 43.7 | 31.9 | |

| Preoperative biliary drainage | 0.632 | ||||

| No | 10 | 35 | 40 | 0.0 | |

| Yes | 35 | 42 | 53.8 | 42.3 | |

| Location | 0.547 | ||||

| MBD | 34 | 42 | 51.4 | 44.1 | |

| PBD-1 | 11 | 52 | 51.9 | 26 | |

| LN dissection | 0.997 | ||||

| D1 | 8 | 42 | 58.3 | 29.2 | |

| D2 | 37 | 52 | 51.2 | 42.6 | |

| Transfusion | 0.832 | ||||

| No | 36 | 42 | 51.2 | 39.4 | |

| Yes | 9 | 33 | 47.6 | 23.8 | |

| Size (cm) | 0.892 | ||||

| ≤ 2.0 | 26 | 35 | 47 | 39.2 | |

| > 2.0 | 19 | 52 | 56.6 | 33.9 | |

| T stage | < 0.001 | ||||

| T1 | 9 | NR | 100 | 100 | |

| T2 | 33 | 35 | 49.6 | 31.5 | |

| T3 | 3 | 16 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| LN stage | 0.010 | ||||

| N0 | 32 | 52 | 63.1 | 42.6 | |

| N1 | 13 | 25 | 19.2 | 19.2 | |

| TNM stage | 0.012 | ||||

| Ia | 9 | NR | 100 | 100 | |

| Ib | 23 | 42 | 55.8 | 32.6 | |

| IIb | 13 | 25 | 19.2 | 19.2 | |

| Cell differentiation | 0.005 | ||||

| Well | 15 | NR | 87.5 | 57.5 | |

| Moderate | 26 | 33 | 41.6 | 33.3 | |

| Poor | 4 | 22 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Perineural invasion | 0.180 | ||||

| No | 13 | NR | 71.1 | 71.1 | |

| Yes | 32 | 35 | 47.7 | 29.8 | |

BDSR: Bile duct segmental resection; CA19-9: Carbohydrate antigen 19-9; MBD: Middle bile duct cancer; PBD-1: Proximal bile duct cancers; LN: Lymph node; NR: Not reached.

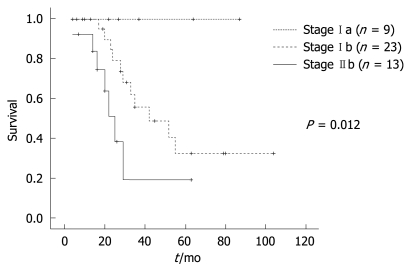

Among the 45 patients, 3 patients (6.6%) underwent additional adjuvant treatment. Two patients with stage Ib each had chemoradiation and radiation. One patient with stage IIb had chemoradiation. There was no evidence of recurrence in all three patients. The recurrence rate was 44.4% (n = 20). The stage specific recurrence rate was as follows: 24.4% (n = 11) for stage Ib and 20.0% (n = 9) for stage IIb. There were 12 locoregional recurrences, 5 liver metastases and 3 peritoneal carcinomatoses. Eleven patients underwent palliative treatment and 9 patients refused to go under extra treatment. The 3- and 5-year survival rates of the BDSR group were 51.7% and 36.6%, respectively. The median survival was 25 mo (mean: 31.27 mo). Univariate analysis showed cellular differentiation (P = 0.005), the T stage (P < 0.001), the LN status (P = 0.010) and the TNM stage (P = 0.012) to be significant factors that influenced patient survival (Table 1, Figure 1). However, there were no statistically significant independent risk factors that influenced patient survival on multivariate analysis.

Figure 1.

Survival according to the TNM stage of 45 patients who underwent bile duct segmental resection (BDSR) for proximal bile duct cancers (PBD-1) or middle bile duct cancer (MBD) disease.

Comparison of survival between the BDSR group and the PD group

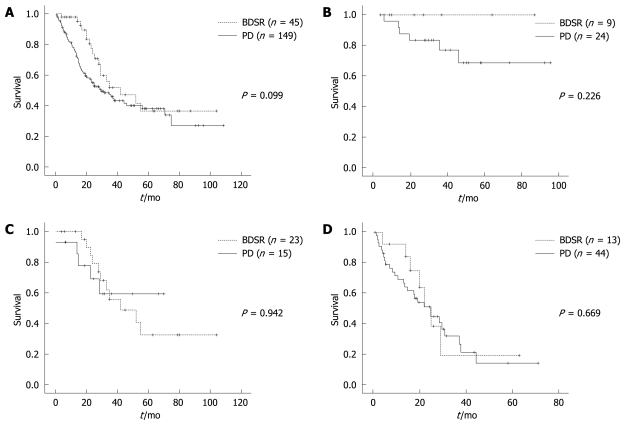

There were 149 patients in the PD group. There were 102 (68.5%) males and 47 (31.5%) females. The median age of the patients was 60 years (range: 31-78 years). Whipple’s procedure was done in 97 (65.1%) patients, pylorus preserving PD was done in 45 (30.2%) patients and total pancreatectomy was done in 7 (4.7%) patients. The median follow-up was 21.9 mo (range: 0.4-108.5 mo). During the follow-up period, 88 (59.1%) patients had recurrences and 78 (52.3%) patients died of cancer-related causes. The survival of the BDSR group was compared with the group of patients who underwent PD for their DBD; these patients are known to have similar clinical characteristics as patients with PBD-1 or MBD (Table 2). The survival rate, postoperative complications and length of the postoperative hospital stay were the factors analyzed. The 3- and 5-year overall survival rates were 51.7% and 36.6% in the BDSR group, and 46.0% and 38.1% in the PD group (P = 0.099) (Figure 2A). The stage specific survival rates were compared between the BDSR group and the PD group. The 3-year and 5-year survival rates of the patients with stage Ia disease were 100.0% and 100.0%, respectively, in the BDSR group, and 76.9% and 68.4%, respectively, in the PD group (P = 0.226) (Figure 2B). The 3-year and 5-year survival rates of the patients with stage Ib disease were 55.8% and 32.6%, respectively, in the BDSR group, and 59.3% and 59.3%, respectively, in the PD group (P = 0.942) (Figure 2C). The 3-year and 5-year survival rates of patients with stage IIb disease were 19.2% and 19.2%, respectively, in the BDSR group, and 31.9% and 14.2%, respectively, in the PD group (P = 0.669) (Figure 2D). Therefore, the BDSR group and the PD group did not show any significant difference in survival when this was adjusted for the TNM stage. Sixty one (40.9%) patients in the PD group experienced postoperative complications (pancreatic fistula, bleeding, delayed gastric emptying, wound infection, intraabdominal abscess, etc.). There were significantly less postoperative complications in the BDSR group (20.0% vs 40.9%, respectively, P = 0.01). The length of the postoperative hospital stay was significantly shorter in the BDSR group (mean: 16.62 d vs 28.35 d, respectively, P = 0.035).

Table 2.

The clinical characteristics of the BDSR group were compared with the PD group n (%)

| Characteristics | BDSR group | PD group |

| Total patients | 45 | 149 |

| Age (median, yr) | 65 (37-76) | 60 (31-78) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 30 (66.7) | 102 (68.5) |

| Female | 15 (33.3) | 47 (31.5) |

| Median follow-up (mo) | 25.0 (4.0-104.0) | 21.9 (0.4-108.5) |

| T stage | ||

| T1 | 9 (20.0) | 32 (21.4) |

| T2 | 33 (73.3) | 20 (13.4) |

| T3 | 3 (6.7) | 90 (60.5) |

| T4 | 0 (0.0) | 7 (4.7) |

| N status | ||

| N0 | 32 (71.2) | 101 (67.8) |

| N1 | 13 (28.8) | 48 (32.2) |

| TNM stage | ||

| Ia | 9 (20.0) | 24 (16.1) |

| Ib | 23 (51.1) | 15 (10.1) |

| IIa | 0 (0.0) | 58 (38.9) |

| IIb | 13 (28.9) | 44 (29.5) |

| III | 0 (0.0) | 8 (5.4) |

PD: Pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Figure 2.

Comparison of survival between the BDSR group and the pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) group. A: The 3-year and 5-year overall survival rates were 51.7% and 36.6%, respectively, for the BDSR group and 46.0% and 38.1%, respectively, for the PD group; B: The 3-year and 5-year survival rates of the patients with stage Ia disease were 100.0% and 100.0%, respectively, for the BDSR group and 76.9% and 68.4%, respectively, for the PD group; C: The 3-year and 5-year survival rates of the patients with stage Ib disease were 55.8% and 32.6%, respectively, for the BDSR group and 59.3% and 59.3%, respectively, for the PD group; D: The 3-year and 5-year survival of patients with stage IIb disease were 19.2% and 19.2%, respectively, for the BDSR group and 31.9% and 14.2%, respectively, for the PD group.

DISCUSSION

Classification of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma according to its anatomic location (proximal, middle, distal) was first proposed by Longmire[13] in 1976. There still exists some debate about the classification of MBD carcinoma since cholangiocarcinomas are very rarely located only in this section of the bile duct without infiltration into the proximal or distal bile duct. So there have been other classifications of the cholangiocarcinomas such as that proposed by Nakeeb et al[14] which results in a simpler classification of intrahepatic, hilar and distal cholangiocarcinoma. Jarnagin et al[15] also proposed a 2-category system of proximal and distal bile duct cancer, with MBD cancer being in a separate category. Such interest in the classification of cholangiocarcinomas is due to the difference in surgical treatment according the different anatomic locations. Intrahepatic and perihilar cholangiocarcinomas are usually treated by liver resection[16-18]. In contrast, distal cholangiocarcinoma requires PD for complete tumor resection. Then what about tumors confined to the MBD? Different surgical treatments are possible for MBD cancers according to the distance between the hilum or the upper border of the pancreas, and also according to the experience and preference of the surgeon. For tumors with negative bile duct margins and no infiltration into vascular structures, BDSR is sometimes undertaken, albeit for only a small proportion of these tumors.

The most important issues for BDSR for PBD-1 or MBD is the radial margin, involvement of the portal vein or hepatic artery and LN dissection[10]. T1 and T2 tumors, and T3 tumors with infiltration only into the gallbladder and without vascular invasion, were included in this study. T3 or T4 tumors with vascular, liver or pancreas invasion require extended surgery due to the fact that R0 resection is impossible with BDSR in these cases. Sufficient radical dissection of the LNs, and especially the LNs around the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), may be another issue. According to the general rules for surgical and pathological studies on cancer of the biliary tract by the Japanese Society of Biliary Surgery, in the case of PBD-1 LNs #12 (a1, a2, b1, b2, c, p1, p2, h) are classified as group 1 and LNs #8 (a, p) and #13 are classified as group 2. For MBD, LNs #12 (b1, b2, c) are classified as group 1 and LNs #12 (a1, a2, c, p1, p2, h), #8 (a, p) and #13 (1) are classified as group 2. Since the LNs around the SMA and #17 are classified as group 3, radical resection LN dissection (D2) is possible with BDSR.

There have been occasional reports of BDSR for treating extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in selected patients[7,8,19-22]. In the series from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center[7], only 13% of patients (6 of 45) were amenable to bile duct excision alone, while this figure was 8% (3 of 34) in the Veterans Hospital study[22]. But in most of these reports, risk factor evaluation was not possible due to the limited number of BDSR cases. In this study, 28.8% of the cases had LN metastases, and the LN status was a significant risk factor that affected survival. Furthermore, the cell differentiation, the T stage and the TNM stage were significant factors that affected the outcomes. It has been reported that the frequency of LN metastasis in DBD ranged from 30% to 68%[7,8,11,14,20,23], and negative LN metastasis was a useful predictor of a favorable outcome for patients with DBD[7,8,14,23]. However, perineural invasion did not prove to be statistically significant, unlike the other studies that reported the risk factors for survival from cholangiocarcinoma in other parts of the biliary tree[24,25].

In the present study, 3 patients underwent BDSR due to the lesion being close to the upper border of pancreas. All 3 patients developed postoperative pancreatitis. Two of these patients developed local recurrence in the remnant distal bile duct at 9 mo and 31 mo, respectively. Although the 2 cases mentioned were categorized as recurrences, they could also have been considered remnant bile duct cancer when the slow-growth of cholangiocarcinoma was taken into account. For a tumor that is close to the upper border of pancreas and resected bile margin reveals to be free of carcinoma, PD should be considered as a treatment option since the pattern of tumor spread along the periductal tissue can be assumed and it should secure sufficient distal bile duct resection margin.

A comparison of survival would be most accurate between 2 groups that received BDSR or PD for carcinoma confined to the proximal or MBD. But this was not feasible due to the small number of patients included in this category. So a different approach was selected in this study, and comparisons were made with the group of patients who received PD for DBD, which is known to have similar clinical characteristics with its proximal counterparts. Although several authors have reported that MBD had a worse prognosis than hilar or distal bile duct cancer[26-28], other authors did not concur[8,29]. According to previous reports, the curative resection rates for DBD have ranged from 56% to 100%[7,8,14,19-22]. However, the 5-year survival rate for DBD is not always high, with some reports showing a range of 14%-47%[7,8,11,14,19-23]. In the present study, the overall 3-year and 5-year survival rates of the BDSR group were 51.7% and 36.6%, respectively, which is similar to other published reports[7,8,11,14,19-23]. The stage specific overall survival between BDSR group and PD group was not statistically significant. The BDSR group had a significantly shorter postoperative length of hospital stay and fewer complications compared to the PD group. This comparison may not be so meaningful when taking into consideration that BDSR is a far less extensive and complicated operative method (fewer anastomoses). Thus, BDSR can be safely applied to patients with bile duct resection margin negative PBD-1 or MBD tumor rather than performing more extensive surgery such as PD.

In conclusion, to achieve a cure, the surgeon must obtain histologically negative margins on both the proximal and distal bile ducts and all tumor-bearing nodal tissue must be removed. BDSR with LN dissection can be an alternative treatment and may be justified in preference to a more radical operation for patients with PBD-1 or MBD when there is no pancreas, liver, vascular invasion and the both bile duct resection margins are negative.

COMMENTS

Background

Although radical bile duct segmental resection (BDSR) is performed by many surgeons in selected cases, there are scant clinical studies on the adequacy of this procedure.

Research frontiers

To validate the adequacy of radical BDSR, the authors compared survival between a radical BDSR group and a pancreaticoduodenectomy group for treating distal bile duct cancers.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Clinicopathological studies on hilar and distal cholangiocarcinomas have been done by many authors, and the results of BDSR for middle bile duct (MBD) have been reported, but most of these studies involved a very limited number of cases, and the number of cases is not enough to justify BDSR as a standard treatment.

Applications

The surgeon must obtain histologically negative margins on both the proximal and distal bile ducts and all tumor-bearing nodal tissue must be removed. BDSR with lymph node dissection can be an alternative treatment and may be justified in preference to a more radical operation for patients with MBD.

Peer review

Even if it is a retrospective study, the data reported are interesting and well documented.

Footnotes

Supported by Grants from IN-SUNG Foundation for Medical Research (C-A7-803-1)

Peer reviewer: Antonio Basoli, Professor, General Surgery “Paride Stefanini”, Università di Roma - Sapienza, Viale del Policlinico 155, Roma 00161, Italy

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Bismuth H, Corlette MB. Intrahepatic cholangioenteric anastomosis in carcinoma of the hilus of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:170–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hadjis NS, Blenkharn JI, Alexander N, Benjamin IS, Blumgart LH. Outcome of radical surgery in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery. 1990;107:597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klempnauer J, Ridder GJ, von Wasielewski R, Werner M, Weimann A, Pichlmayr R. Resectional surgery of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:947–954. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pichlmayr R, Weimann A, Klempnauer J, Oldhafer KJ, Maschek H, Tusch G, Ringe B. Surgical treatment in proximal bile duct cancer. A single-center experience. Ann Surg. 1996;224:628–638. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199611000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke EC, Jarnagin WR, Hochwald SN, Pisters PW, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: patterns of spread, the importance of hepatic resection for curative operation, and a presurgical clinical staging system. Ann Surg. 1998;228:385–394. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamberlain RS, Blumgart LH. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a review and commentary. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:55–66. doi: 10.1007/s10434-000-0055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Lin E, Fortner JG, Brennan MF. Outcome of treatment for distal bile duct cancer. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1712–1715. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800831217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kayahara M, Nagakawa T, Ohta T, Kitagawa H, Tajima H, Miwa K. Role of nodal involvement and the periductal soft-tissue margin in middle and distal bile duct cancer. Ann Surg. 1999;229:76–83. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199901000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Ohge H, Sueda T. Prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and surgical margin status for distal cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:207–212. doi: 10.1002/jso.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakamoto Y, Kosuge T, Shimada K, Sano T, Ojima H, Yamamoto J, Yamasaki S, Takayama T, Makuuchi M. Prognostic factors of surgical resection in middle and distal bile duct cancer: an analysis of 55 patients concerning the significance of ductal and radial margins. Surgery. 2005;137:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zerbi A, Balzano G, Leone BE, Angeli E, Veronesi P, Di Carlo V. Clinical presentation, diagnosis and survival of resected distal bile duct cancer. Dig Surg. 1998;15:410–416. doi: 10.1159/000018654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz A, Balch CM, Haller DG, Morrow M. AJCC cancer staging handbook. 6th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longmire WP Jr. Tumors of the extrahepatic biliary radicals. Curr Probl Cancer. 1976;1:1–45. doi: 10.1016/s0147-0272(76)80006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, Coleman J, Abrams RA, Piantadosi S, Hruban RH, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg. 1996;224:463–473; discussion 473-475. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Gonen M, Burke EC, Bodniewicz BS J, Youssef BA M, Klimstra D, Blumgart LH. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:507–517; discussion 517-519. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyagawa S, Makuuchi M, Kawasaki S, Hayashi K, Harada H, Kitamura H, Seki H. Outcome of major hepatectomy with pancreatoduodenectomy for advanced biliary malignancies. World J Surg. 1996;20:77–80. doi: 10.1007/s002689900014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyazaki M, Ito H, Nakagawa K, Ambiru S, Shimizu H, Shimizu Y, Kato A, Nakamura S, Omoto H, Nakajima N, et al. Aggressive surgical approaches to hilar cholangiocarcinoma: hepatic or local resection? Surgery. 1998;123:131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Kondo S, Nagino M, Uesaka K, Oda K, Sano T, Yamamoto H, Hayakawa N. Aggressive preoperative management and extended surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Nagoya experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:155–162. doi: 10.1007/s005340050170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SW, Park YS, Chung JB, Kang JK, Kim KS, Choi JS, Lee WJ, Kim BR, Song SY. Patterns and relevant factors of tumor recurrence for extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma after radical resection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1612–1618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasaki R, Takahashi M, Funato O, Nitta H, Murakami M, Kawamura H, Suto T, Kanno S, Saito K. Prognostic significance of lymph node involvement in middle and distal bile duct cancer. Surgery. 2001;129:677–683. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.114555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki M, Unno M, Oikawa M, Endo K, Katayose Y, Matsuno S. Surgical treatment and postoperative outcomes for middle and lower bile duct carcinoma in Japan--experience of a single institute. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:650–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wade TP, Prasad CN, Virgo KS, Johnson FE. Experience with distal bile duct cancers in U.S. Veterans Affairs hospitals: 1987-1991. J Surg Oncol. 1997;64:242–245. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199703)64:3<242::aid-jso12>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshida T, Matsumoto T, Sasaki A, Morii Y, Aramaki M, Kitano S. Prognostic factors after pancreatoduodenectomy with extended lymphadenectomy for distal bile duct cancer. Arch Surg. 2002;137:69–73. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhuiya MR, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Kondo S, Fukata S, Hayakawa N, Shionoya S. Clinicopathologic studies on perineural invasion of bile duct carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1992;215:344–349. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199204000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jang JY, Kim SW, Park DJ, Ahn YJ, Yoon YS, Choi MG, Suh KS, Lee KU, Park YH. Actual long-term outcome of extrahepatic bile duct cancer after surgical resection. Ann Surg. 2005;241:77–84. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000150166.94732.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagorney DM, Donohue JH, Farnell MB, Schleck CD, Ilstrup DM. Outcomes after curative resections of cholangiocarcinoma. Arch Surg. 1993;128:871–877; discussion 877-879. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420200045008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tompkins RK, Thomas D, Wile A, Longmire WP Jr. Prognostic factors in bile duct carcinoma: analysis of 96 cases. Ann Surg. 1981;194:447–457. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198110000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhuiya MR, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Kondo S, Nagino M, Hayakawa N. Clinicopathologic factors influencing survival of patients with bile duct carcinoma: multivariate statistical analysis. World J Surg. 1993;17:653–657. doi: 10.1007/BF01659134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Todoroki T, Kawamoto T, Koike N, Fukao K, Shoda J, Takahashi H. Treatment strategy for patients with middle and lower third bile duct cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88:364–370. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]