Abstract

There is growing evidence to suggest that clinical psychologists would benefit from more training in sleep and sleep disorders. Sleep disturbances are commonly comorbid with mental health disorders and this relationship is often bidirectional. In addition, psychologists have become integral members of multidisciplinary sleep medicine teams and there are not enough qualified psychologists to meet the clinical demand. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the current education on sleep and sleep disorders provided to clinical psychology predoctoral students and interns. Directors of graduate programs and internships (N = 212) completed a brief online survey on sleep education in their program. Only 6% of programs offers formal didactic courses in sleep, with 31% of programs offering training in the treatment of sleep disorders. There are few programs with sleep faculty (16%), and most reported that their institutions were ineffective in providing sleep education. Thirty-nine percent of training directors reported they would implement a standard curriculum on sleep, if available. The findings from this study suggest that more opportunities are needed for trainees in clinical psychology to gain didactic and clinical experience with sleep and sleep disorders.

Keywords: sleep, education, clinical psychology, training

Introduction

The average person spends approximately one third of his or her life sleeping. Yet health care professionals, including psychologists, know little about the diagnosis and treatment of sleep problems. This is in contrast to the level of education and training in the diagnosis and treatment of daytime problems, including physical and mental health disorders. There are multiple reasons why training in sleep and sleep disorders is beneficial for clinical psychologists. Sleep problems are highly prevalent, affecting approximately 75% of adults (National Sleep Foundation, 2005) and 25–40% of children (Owens, 2005). A complex bidirectional relationship exists between sleep problems and mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, and traumatic stress disorders (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994). Clinically there is an increasing demand for psychologists to join multidisciplinary sleep teams, providing behavioral intervention and support for insomnia, narcolepsy, and adherence to treatment for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA; Pack, 2007).

Over the past 10 years there have been three unpublished reports and surveys that provided limited information about training in sleep for predoctoral psychology students (Lichstein et al., 1998; Pflugardt-Lang, 1997; Stepanski & Perlis, 2003), with no published studies examining the types of didactic or clinical experiences offered during graduate school/internship or describing the efficacy of programs in providing education about sleep to their trainees. In contrast, there have been a number of published studies focusing on sleep education for medical students and residents, showing only a minimal level of success in preparing medical trainees to diagnose and treat sleep disorders (Rosen, Rosekind, Rosevear, Cole, & Dement, 1993; Rosen et al., 1998; Stores & Crawford, 1998). One study found that preclinical medical students receive an average of approximately one hour of sleep education, with 37% of schools reporting no sleep education. During internship and residency, the amount of training decreases with only 23% of programs reporting at least 1 hour of training in sleep and sleep disorders (Rosen et al., 1993). Additional studies have looked at residency programs (including neurology, psychiatry, family practice, and pediatrics), with few programs offering more than 5 hours of concentrated teaching on sleep (Mindell, Moline, Zendell, Brown, & Fry, 1994; Moline & Zendell, 1993). The American Sleep Disorders Association Taskforce on Medical Education in Sleep and Sleep Disorders found that, on average, the majority of medical students, residents, and fellows received less than 2 hours of training in sleep (Rosen et al., 1998). Together these studies highlight the gaps in physician education about sleep and sleep disorders.

This lack of medical education can be seen in current medical practice. Two studies examined the knowledge of sleep and sleep disorders in physicians (Owens, 2001; Papp, Penrod, & Strohl, 2002). Papp and colleagues (2002) reported that the overall mean score on a test of sleep knowledge in primary care physicians was 34%. Owens (2001) found that primary care pediatricians got only 60% of questions on a test of sleep knowledge correct, with almost one out of four pediatricians scoring less than 50%. To try to alleviate this lack of training, the NIH established the Sleep Academic Award program, a program to increase sleep education in medical training. Over an 8-year period, faculty in 20 different medical schools were supported to develop programs and to help educate colleagues at their institutions on the importance of sleep (Rosen & Zozula, 2000).

As previously mentioned, along with other health care providers psychologists also need training in the diagnosis and treatment of sleep problems. Sleep disturbances are commonly comorbid with mental health disorders and this relationship is often bidirectional. For example, insomnia has been found to be one of the most predictive risk factors for the future development of depression (Breslau, Roth, Rosenthal, & Andreski, 1996; Ohayon & Roth, 2003; Perlis, Giles, Buysse, Tu, & Kupfer, 1997) and increases the severity of mood disorder symptoms (Benca, 2005). In the other direction, insomnia is a key symptom of depression and patients with depression often have irregularities in their sleep architecture (Armitage, Trivedi, Hoffmann, & Rush, 1997; Benca, 2005; Ivanenko, Crabtree, & Gozal, 2004). Other studies have also found relationships between sleep disruptions and psychiatric disorders, including anxiety and traumatic stress disorders (Dow, Kelsoe, & Gillin, 1996; Mellman, Kulick-Bell, Ashlock, & Nolan, 1995; Monti & Monti, 2000). Bidirectional relationships have also been reported between sleep and medical problems. For example, insomnia often contributes to pain severity while pain can cause prolonged sleep onset (Affleck, Urrows, Tennen, Higgins, & Abeles, 1996; Lewin & Dahl, 1999; Menefee et al., 2000). Thus, it is important for psychologists to know how to inquire about sleep problems, provide support and interventions for sleep problems, as well as know when to refer patients for further evaluation of sleep disorders such as sleep-disordered breathing or restless legs syndrome (RLS) that interfere with sleep quantity and quality.

Clinical psychologists have also played an increasingly important role in the treatment of sleep disorders. For example, cognitive–behavioral treatment for insomnia (CBT-I) has been found to be as effective as hypnotic medications for short-term treatment of insomnia (Morgenthaler, Kramer et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2002), and more effective than medications for the longer term management of insomnia (Morin, Colecchi, Stone, Sood, & Brink, 1999). A recent National Institute of Health (NIH) state-of-the-science conference statement on insomnia also concluded that cognitive–behavioral treatments of insomnia are as effective in the short-term and more effective in the long-term for the treatment of insomnia (NIH, 2005). Behavioral treatments (e.g., extinction, graduated extinction, preventive education) have also been empirically validated in the treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in young children, resulting in a recent standards of practice statement for their efficacy by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM; Morgenthaler, Owens et al., 2006). Recent studies have also shown that behavioral approaches can improve adherence to positive airway pressure (PAP), a common, yet somewhat unpleasant treatment for obstructive sleep apnea in adults (Aloia, Arnedt, Stepnowsky, Hecht, & Borrelli, 2005; Aloia et al., 2007) and children (Marcus et al., 2006; Slifer et al., 2007).

Because of the efficacy of behavioral treatments for certain sleep disorders, as well as the interdisciplinary nature of sleep medicine (Meltzer, Moore, & Mindell, 2008; Pack, 2007), the AASM (2007) has required that sleep centers demonstrate the ability and experience in the diagnosis and treatment of all types of sleep disorders to become accredited. This includes the availability of recognized treatments like CBT-I or graduated extinction either within a center or by referral, suggesting the need for psychologists to provide these interventions (AASM, 2007). Furthermore, the recent Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2006) report on sleep and sleep deprivation included as one of its top four recommendations that sleep programs in academic health centers be organized as interdisciplinary programs that encompass the relevant clinical disciplines, including psychology.

Given the need to understand normal sleep and sleep disorders within the general practice of clinical psychology, as well as the rising demand for clinical psychologists to work in the area of sleep medicine, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the current education provided to graduate students and predoctoral interns in APA- or Canadian Psychological Association (CPA-)–approved clinical psychology programs. This information will help determine how much training on sleep and sleep disorders is available within clinical psychology training programs, as well as what resources could be used to assist training programs in the development and integration of a sleep curriculum in their programs.

Method

Participants

Study participants included directors of clinical training and internship directors. To maintain confidentiality, demographic information was not collected on participants. Contact information was located for 743 APA- or CPA-approved clinical psychology graduate programs and internship sites. As some sites have both graduate and internship programs, 715 training directors were invited by e-mail to participate in this study. Two-hundred twelve directors completed the survey (30% participation), providing information for 45 PhD programs, 12 PsyD programs, 142 internship sites, and 13 programs with a combination of training opportunities (PhD, PsyD, internships). The programs had a median of 24.5 predoctoral students (range = 1–500 students), a median of 6 predoctoral interns (range = 1–65), and a median of 10 fulltime faculty (range = 2–200) and 3 part-time faculty members (range = 1–150).

Procedure

An e-mail was sent to all program directors explaining the purpose of the study, and inviting the participants to complete a brief Web-based survey inquiring about the extent to which education about sleep and sleep disorders is part of their doctoral-level clinical psychology and/or internship program. The study was approved by a university institutional review board, and participants’ completion of the survey served as their consent. All responses were anonymous with no identifying information about the training directors collected. A second e-mail reminder was sent to all directors approximately 2 weeks after the initial request for participation.

Measure

Sleep education in psychology

This 19-item questionnaire (Appendix) was designed based on questionnaires used in a study of sleep training for medical professionals (Rosen et al., 1998). Questions focused on the number of faculty specializing in sleep, the availability of sleep education, and beliefs about the effectiveness of their program in training students about sleep and sleep disorders.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses (frequency, mean) were used to examine the type and amount of training in sleep offered by programs. Chi-square analyses were used to determine if the frequency of training opportunities differed between program types.

Results

Program Comparisons

To examine differences between the different types of programs (PhD, PsyD, internship, combined) in training opportunities and training needs, chi-square analyses were conducted (Table 1). No significant differences were found between the four program types. To ensure that the lack of differences was not being masked by to the small number of PsyD and combined programs, additional analyses were conducted comparing graduate only (PhD + PsyD) and internship only programs, again with no significant differences.

Table 1.

Percentage of Programs Offering Training Opportunities in Sleep

| PhD (n = 45) |

PsyD (n = 12) |

Internship (n = 142) |

Combined (n = 13) |

Total (N = 212) |

χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Course on sleep offered | 4.7 | 0 | 7.6 | 0 | 6.1 | 2.09 |

| Sleep incorporated into other aspects of training | ||||||

| Lectures in another course | 22.2 | 16.7 | 12.0 | 23.1 | 15.1 | 3.53 |

| Lectures in weekly | 22.2 | 8.3 | 15.5 | 0 | 15.6 | 4.39 |

| education series | ||||||

| Guest lecture/grand rounds | 31.1 | 50.0 | 32.4 | 25.0 | 32.7 | 2.01 |

| Clinic patients | 28.9 | 16.7 | 26.8 | 38.5 | 27.4 | 1.58 |

| If available, would these resources assist in the training of your students in sleep and sleep disorders | ||||||

| Textbooks | 42.2 | 33.3 | 33.8 | 30.8 | 35.4 | 1.22 |

| Videos | 68.9 | 75.0 | 59.2 | 84.6 | 63.7 | 4.91 |

| Online education | 60.0 | 41.7 | 44.4 | 46.2 | 47.6 | 3.55 |

| Case studies | 51.1 | 41.7 | 48.6 | 53.8 | 49.1 | 0.47 |

Didactic Sleep Education

Only 6% (n = 12) of the programs offered a formal course in sleep, with 10 of these programs self-identifying as internship training programs. Fifty-nine percent of programs offered sleep education as part of at least one other aspect of training, including another course (15%), weekly education series (16%), guest lectures/grand rounds (33%), and clinic patients (27%). Guest lectures/grand rounds were the most common education forum for sleep for both PhD programs and internships.

Clinical Sleep Training

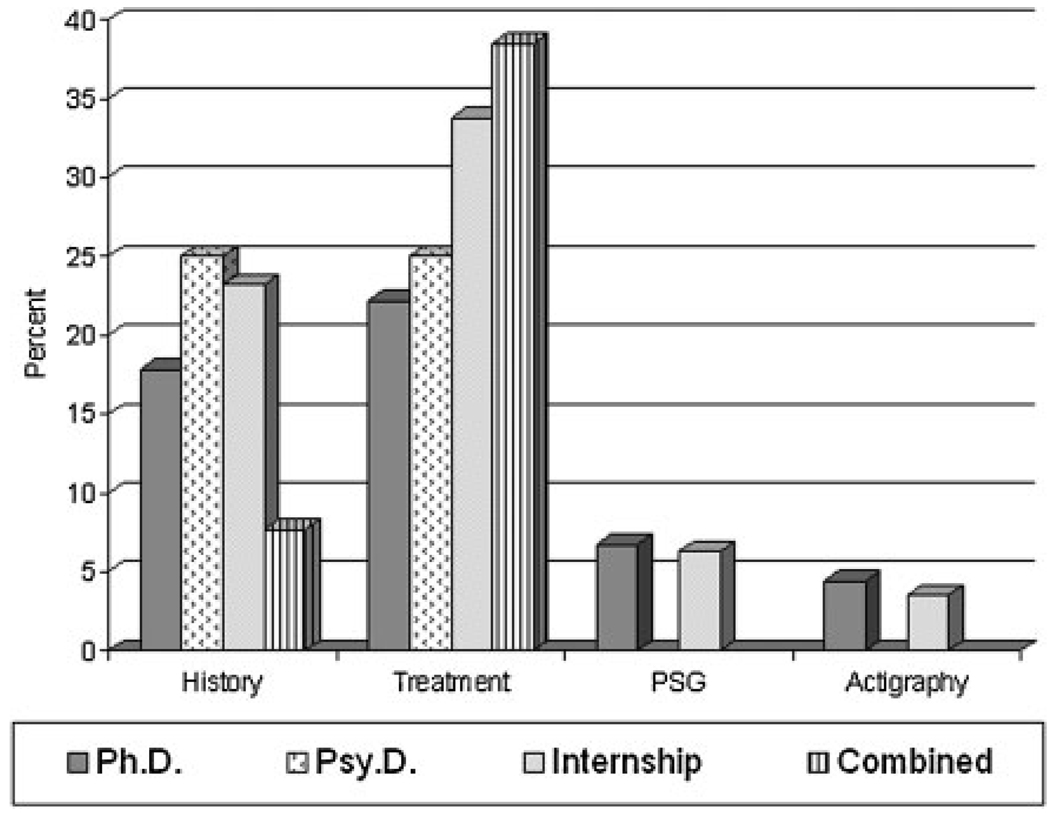

Across all programs, clinical sleep training included the assessment of a sleep disorder through a sleep history (21%), treatment of sleep disorders (31%), diagnosis of sleep disorders in a sleep lab by polysomnography (6%), and diagnosis of a sleep disorder with actigraphy (6%). Figure 1 shows the percentage of each type of program that offered at least one of these sleep training experiences. Notably, 41% of respondents reported that they failed to offer any clinical training in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of sleep disorders. This lack of training included 47% of PhD programs, 58% of PsyD programs, 39% of internships, and 39% of combined programs. For programs where students were involved with practicum or internship placements, only 5% offered a rotation in a sleep center and 18% offered a rotation at a site that typically included patients with sleep-related issues.

Figure 1.

Percentage of programs offering clinical sleep training experiences.

Faculty With Specializations in Sleep

Only 33 of the 212 programs (17%) reported at least one faculty member who specialized in at least one area of sleep or circadian rhythms. Of those who reported having faculty who specialize in sleep, 38% focused exclusively on adult sleep, 19% specialized in only pediatric sleep, 3% focused on only geriatric sleep, with the remainder (40%) focusing on a combination of age groups. As seen in Table 2, programs with faculty who specialized in sleep or circadian rhythms were more likely to offer a course dedicated to sleep. Significantly more clinical training opportunities were also available in programs with sleep faculty. However, no differences were found between programs with and without sleep faculty in terms of integrated sleep training (e.g., part of another course, weekly lecture, grand rounds).

Table 2.

Percentage of Programs With Faculty Who Specialize in Sleep or Circadian Rhythms Offering Training Opportunities in Sleep

| Faculty (N = 33) | No faculty (N = 167) | χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Course on sleep offered | 25.0 | 2.4 | 23.71 | <0.001 |

| Clinical sleep training opportunities | ||||

| Sleep lab | 27.3 | 1.8 | 31.71 | <0.001 |

| Sleep history | 57.6 | 15.6 | 24.88 | <0.001 |

| Actigraphy | 21.2 | 0.0 | 36.71 | <0.001 |

| Treatment for sleep disorders | 66.7 | 25.7 | 21.03 | <0.001 |

| Sleep incorporated into other aspects of training | ||||

| Lectures in another course | 12.2 | 15.6 | 0.26 | n.s. |

| Lectures in weekly education series | 21.2 | 13.8 | 0.27 | n.s. |

| Guest lecture/grand rounds | 36.4 | 31.9 | 0.25 | n.s. |

| Clinic patients | 30.3 | 26.3 | 0.22 | n.s. |

Need for Sleep Curriculum

Directors were asked if they would implement a standardized sleep curriculum if such a program existed. Thirty-nine percent of program directors reported that they would implement such a program. Participants were most interested in a curriculum that included information on treatment of sleep disorders (68%), followed by diagnostic criteria for sleep disorders (61%), developmental features of sleep (52%), prevention of sleep disorders (52%), and evaluation of sleep disorders (50%). Both graduate program directors and internship directors reported that they believed videos would be the most effective training resource to teach their students and interns about sleep and sleep disorders.

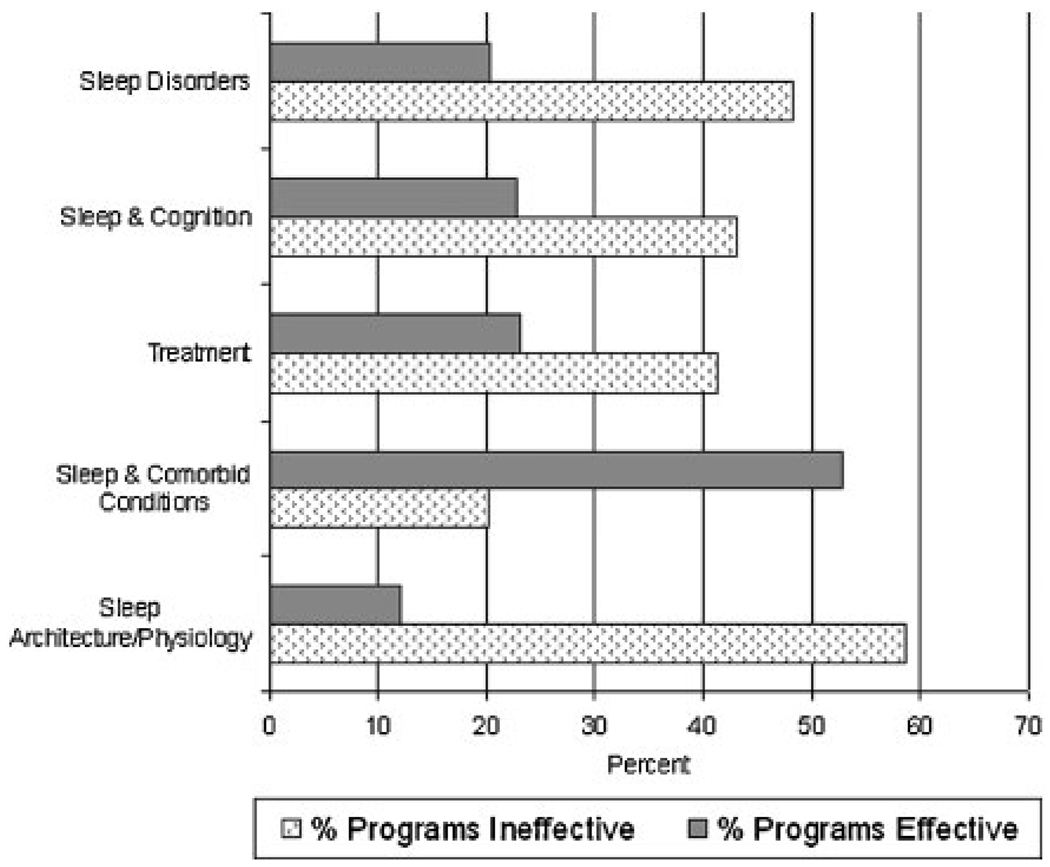

Institutional Effectiveness of Training in Sleep and Sleep Disorders

Program directors also were asked to evaluate the effectiveness of their institution in teaching about sleep in the following areas: sleep disorders, sleep and cognition, treatment of sleep disorders, sleep and comorbid conditions (e.g., anxiety, depression), and sleep architecture/physiology. As seen in Table 3, approximately half (53%) of the respondents reported that their institution was effective (moderately or extremely) in the teaching of sleep and concomitant disorders. However, less than one out of four programs thought their institution was effective in the teaching of sleep disorders, sleep and cognition, and the treatment of sleep disorders, with only 13% of programs reporting being effective (moderately or extremely) in the teaching of sleep architecture/physiology (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Institutional Effectiveness in Sleep Education Reported by Training Directors (%)

| Extremely ineffective |

Moderately ineffective |

Neutral | Moderately effective |

Extremely effective |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep disorders | 22.6 | 25.6 | 31.5 | 15.5 | 4.8 |

| Sleep and cognition | 20.4 | 22.8 | 34.1 | 19.8 | 3.0 |

| Treatment of sleep disorders | 18.8 | 22.4 | 35.8 | 17.0 | 6.1 |

| Sleep and comorbid conditions | 7.1 | 13.0 | 27.2 | 42.6 | 10.1 |

| Sleep architecture/ physiology | 32.3 | 26.3 | 29.3 | 10.2 | 1.8 |

Figure 2.

Percentage of programs self-identified as effective or ineffective in providing sleep education.

Discussion

This survey of clinical psychology graduate and internship programs indicates that there are gaps in training in sleep and sleep disorders for predoctoral psychology students. Based on our findings, we draw the following conclusions: (a) didactic education on sleep is rarely provided to trainees, with only 6% of programs offering a specialized didactic course in sleep; (b) clinical training on the diagnosis and treatment of both primary and secondary sleep disorders is limited, with few programs offering training in the taking of a sleep history (21%) or the treatment of sleep disorders (31%), and 41% of programs offering no training in any aspect of diagnosis and treatment; (c) programs are limited by a small number of faculty who specialize in sleep or circadian rhythms; (d) there is an interest in a standard curriculum in sleep among 39% of graduate and internship programs; and (e) psychology training programs are currently most effective in providing students education in the area of sleep and comorbid conditions and least effective in providing education about sleep architecture/physiology.

Compared to previously unpublished reports on training opportunities in sleep or behavioral sleep medicine, our results show that over the past 10 years the number of programs with concentrated training in sleep has been maintained at approximately 5–6%. A study featured in an unpublished dissertation from 1997 found that almost two thirds of clinical psychology graduate programs (N = 59, includes both doctoral and masters degree programs) had less than 60 minutes of education about sleep and sleep disorders, with only three programs (5.6%) offering more than 4 hours of education in this area (Pflugardt-Lang, 1997). A 1998 report provided to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine about sleep training in clinical psychology programs reported only 5% (N = 6) of the responding APA-accredited clinical psychology programs had systematic training available (academic, research, and clinical), with an additional 14% (N = 19) of programs providing minimal training (1 or 2 components; Lichstein et al., 1998). In a 2003 summary of training opportunities in behavioral sleep medicine, the number of programs was also similar to our results (nine graduate programs, five internship programs, and seven combined programs; Stepanski & Perlis, 2003). The current study results are also similar to reports of medical school and residency training (Rosen & Zozula, 2000).

However, the results of this study are limited by methodological issues. Because of the small self-selected sample, it is possible that the results reported here either under- or overestimate the amount and type of sleep education currently provided for psychology trainees. In our opinion it is likely to be an overestimation, as programs that offer sleep education were probably more likely to respond. Due to the anonymous nature of the survey, we were unable to return to participants to further query responses or gather additional information from programs that offer didactic and/or clinical training in sleep. In addition, this study looked only at clinical and didactic training opportunities, and did not inquire about ongoing student involvement in sleep-related research studies. It is possible that the training received in experimental psychology research labs or related to studies of behavioral interventions for sleep problems was not accounted for in this study. These research opportunities may provide an additional gateway to a career in the field of sleep for clinical psychologists.

Despite these limitations, this study demonstrates that psychology trainees receive minimal, if any, training about sleep and sleep disorders. Considering the high prevalence of sleep disorders in the United States, additional training is needed for clinical psychologists, in particular in the diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders. It is estimated that approximately one third of adults and 25–40% of children experience symptoms of insomnia that would likely respond to behavioral treatment (Ohayon, 2002; Owens, 2005). As stated previously, CBT-I has been shown to be equivalent to pharmacological interventions in the short term for sleep in adults (Morin, Hauri et al., 1999; Smith et al., 2002), with behavioral treatment effects lasting up to 24 months, whereas the benefits of pharmacological interventions are lost with the discontinuation of treatment (Morin, Colecchi et al., 1999). Similarly, behavioral interventions have been empirically validated for bedtime problems and night wakings in young children (Mindell, Kuhn, Lewin, Meltzer, & Sadeh, 2006). Currently, clinical psychologists anecdotally report being unable to meet the demand of patients seeking treatment for insomnia, and the results of this study suggest that this shortage will likely continue if additional curricula are not added to both graduate and internship training programs.

As trainees pursue new and different career paths, there is a high demand for psychologists who are trained and certified in behavioral sleep medicine. Currently, only 79 psychologists are certified in behavioral sleep medicine by the AASM (out of 108 clinicians), and there are only five accredited behavioral sleep medicine training programs in the United States. Both the AASM and the IOM have stated that psychologists are needed as integral members of interdisciplinary sleep medicine teams. This means that there are potential employment opportunities for psychologists who have specialty training in this area.

Although students need additional training in the area of sleep and sleep disorders, there are a number of obstacles that graduate programs and internships currently face, primarily with the lack of faculty who have the knowledge and experience to provide this education. We found that most concentrated sleep training opportunities (e.g., dedicated course, clinical training in sleep) were faculty driven, thus it would be preferable to add new faculty with expertise in sleep to programs. However, there is a shortage of such individuals as previously discussed. Further, the cost of faculty start-up combined with the cost of adding students who might be interested in the area of study is prohibitive to many programs. Additional obstacles faced by all graduate programs (including psychology and medicine) are the lack of time in the training program for additional courses, as well as the competition with existing training requirements (Stepanski & Perlis, 2003).

These barriers suggest the need for a brief standard curriculum to be developed that can be implemented by current faculty at graduate and internship programs. There are examples of programs that have been successful in implementing such programs. For example, one health center implemented a 10-session in-service training program during noon conferences for medical residents and attending physicians (Zozula, Rosen, Jahn, & Engel, 2005). Over the 3 years that this program was offered, the prevalence of diagnosed sleep disorders increased from 11 to 26%. Another program offered a 3.5-hour role-play workshop to family medicine students, with almost two out of three students reporting the application of this information to their clinical practice (Schillinger, Kushida, Fahrenbach, Dement, & LeBaron, 2003).

Similar brief interventions should be developed for psychology training programs. In particular, core curricula are needed for developmental aspects of sleep across the lifespan, the diagnosis of sleep disorders, and the implementation of cognitive–behavioral therapy for insomnia. With today’s technology, a combination of video and online modules would be easily accessible and not very expensive for both faculty and students. By providing education in sleep to psychologists at all levels, current and future students will become better trained on the diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders. Based on the success of the NIH Sleep Academic Award Program, to help aid the development of such brief intervention programs perhaps it is time for a similar initiative that will address the training gaps in clinical psychology.

Overall, this study indicates that psychology trainees receive minimal training in sleep and sleep disorders. Development of education programs to rectify this lack of training would likely result in not only improved assessment and treatment of sleep problems, but also increased employment opportunities for clinical psychologists.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the training directors who participated in this study, and our research assistants, Kelly Ann Davis and Jillian Hopson, who assisted with identifying eligible programs and data cleaning. The preparation of this article was supported in part by K23MH077662 awarded by the NIMH to the first author (L.J.M).

Appendix

Sleep Education Questionnaire

- What programs are offered at your institution? Please check all that apply.

- PhD

- PsyD

- Internship

- Other: (please specify)

How many students are in your graduate program?

How many faculty members do you have?

- Is sleep or circadian rhythms an area of specialty for any of your faculty members?

- Yes

- No

How many faculty members specialize in sleep or circadian rhythms?

- What specialty area(s) do they focus on? Please check all that apply.

- Pediatric

- Adult

- Elderly

- Cognitive–behavioral therapy

- Neuropsychology

- Health

- Insomnia

- Circadian rhythm

- Parasomnias (sleepwalking/talking, nightmares, etc.)

- Other: (please specify)

Does your program offer a course on sleep to graduate students/interns?

What course(s)? (Please list.) Was that course required or an elective? How many students were in the class?

Is sleep incorporated in other aspects of training? (Such as lecture as a part of another course, in a weekly lecture series, guest lectures/grand rounds, clinic patients, etc.)

- Which of the following were included in your program?

- Lecture as part of another course

- Lectures in weekly education series

- Guest lecture/grand rounds

- Clinic patients

- Other: (please specify)

If included as a part of another course, what course(s)? (List each.) Was that course required or an elective? How many students were in the class?

- Does your program offer any training in any of the following? Please check all that apply.

- Sleep laboratory experience (polysomnography, multiple sleep latency tests, etc.)

- Sleep history interviewing skills

- Actigraphy

- Treatment of sleep disturbances (insomnia, pediatric sleep disorders, etc.)

- None of the above

- Other: (please specify)

- Approximately, how many clients/patients does a trainee see who has a:

- Primary sleep disorder

- Concomitant sleep disorder (ex. depression and insomnia)

- Approximately, how many clients/patients with primary sleep disorder does a trainee see who is:

- Pediatric

- Adult

- Elderly

- For students involved in practicum sites or an internship, do you offer any of the following in relation to sleep:

- Rotation in a sleep center

- Rotation in a site that typically includes patients with sleep-related issues

- No sleep practicum or clinical training experiences offered

- Other: (please specify)

- How would you rate your institution’s effectiveness in teaching about sleep on the following topics? (Extremely Effective, Moderately Effective, Neutral, Moderately Ineffective, Extremely Ineffective)

- Sleep disorders

- Sleep and cognition

- Treatment of disorder

- Sleep and comorbid conditions (ex. anxiety, depression)

- Sleep architecture/physiology

- If any of the following resources were available, would any of the items listed below assist in the training of your students in sleep and sleep disorders? Check all that you would find helpful.

- Textbooks

- Videos

- Online education support

- Case studies

- Other: (please specify)

- If there were a standardized curriculum in sleep, would you be likely to use it in your program?

- Yes

- No

- Of the following topics, which would you find helpful in a curriculum for sleep?

- Diagnostic criteria for sleep disorders

- Evaluation of sleep disorders (EEG, PSG, interviewing, etc.)

- Treatment of sleep disorders (medical, behavioral, etc.)

- Sleep hygiene/stimulus control/relaxation techniques

- Biological rhythms and physiology

- Preventive measures

- Developmental differences (across the lifespan)

- Other: (please specify)

Other comments:

Contributor Information

Lisa J. Meltzer, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and The University of Pennsylvania

Cindy Phillips, Drexel University.

Jodi A. Mindell, Saint Joseph’s University, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and The University of Pennsylvania

References

- Affleck G, Urrows S, Tennen H, Higgins P, Abeles M. Sequential daily relations of sleep, pain intensity, and attention to pain among women with fibromyalgia. Pain. 1996;68:363–368. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloia MS, Arnedt JT, Stepnowsky C, Hecht J, Borrelli B. Predicting treatment adherence in obstructive sleep apnea using principles of behavior change. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2005;1:346–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloia MS, Smith K, Arnedt JT, Millman RP, Stanchina M, Carlisle C, et al. Brief behavioral therapies reduce early positive airway pressure discontinuation rates in sleep apnea syndrome: Preliminary findings. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2007;5:89–104. doi: 10.1080/15402000701190549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Standards for Accreditation of Sleep Disorders Centers. [Retrieved December 10, 2007];Chicago; 2007 from http://aasmnet.org/AccredStandards.aspx.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: Author; 1994

- Armitage R, Trivedi M, Hoffmann R, Rush AJ. Relationship between objective and subjective sleep measures in depressed patients and healthy controls. Depression and Anxiety. 1997;5:97–102. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1997)5:2<97::aid-da6>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benca RM. Mood disorders. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and practices of sleep medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. pp. 1311–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: A longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biological Psychiatry. 1996;39:411–418. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow BM, Kelsoe JR, Jr, Gillin JC. Sleep and dreams in Vietnam PTSD and depression. Biological Psychiatry. 1996;39:42–50. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: An unmet public health problem. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006 [PubMed]

- Ivanenko A, Crabtree VM, Gozal D. Sleep in children with psychiatric disorders. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2004;51:51–68. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(03)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin DS, Dahl RE. Importance of sleep in the management of pediatric pain. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1999;20:244–252. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199908000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichstein KL, Nichols C, Perlis ML, Stepanski EJ, Tatman J, Waters W. Report on sleep training in clinical psychology programs. Chicago: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 1998

- Marcus CL, Rosen G, Ward SL, Halbower AC, Sterni L, Lutz J, et al. Adherence to and effectiveness of positive airway pressure therapy in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e442–e451. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellman TA, Kulick-Bell R, Ashlock LE, Nolan B. Sleep events among veterans with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:110–115. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer LJ, Moore M, Mindell JA. The need for interdisciplinary pediatric sleep clinics. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2008;6:268–282. doi: 10.1080/15402000802371395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menefee LA, Cohen MJM, Anderson WR, Doghramji K, Frank ED, Lee H. Sleep disturbance and nonmalignant chronic pain: A comprehensive review of the literature. Pain Medicine. 2000;1:156–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2000.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell JA, Kuhn B, Lewin DS, Meltzer LJ, Sadeh A. Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006;29:1263–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell JA, Moline ML, Zendell SM, Brown LW, Fry JM. Pediatricians and sleep disorders: Training and practice. Pediatrics. 1994;94:194–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moline ML, Zendell SM. Sleep education in professional training programs. Sleep Research. 1993;22:1. [Google Scholar]

- Monti JM, Monti D. Sleep disturbance in generalized anxiety disorder and its treatment. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2000;4:263–276. doi: 10.1053/smrv.1999.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenthaler T, Kramer M, Alessi C, Friedman L, Boehlecke B, Brown T, et al. Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: an update. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 2006;29:1415–1419. [PubMed]

- Morgenthaler TI, Owens J, Alessi C, Boehlecke B, Brown TM, Coleman J, et al. Practice parameters for behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 2006;29:1277–1281. [PubMed]

- Morin CM, Colecchi C, Stone J, Sood R, Brink D. Behavioral and pharmacological therapies for late-life insomnia: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:991–999. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.11.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, Hauri PJ, Espie CA, Spielman AJ, Buysse DJ, Bootzin RR. Nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine review. Sleep. 1999;22:1134–1156. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.8.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Sleep Foundation. Sleep in America Poll. [Retrieved January 7, 2008];2005 from http://www.sleepfoundation.org.

- National Institute of Health. NIH State-of-the Science Conference Statement on Manifestations and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults; NIH Consensus Science Statements; Bethesda, MD: Author; 2005. pp. 1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: What we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2002;6:97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon MM, Roth T. Place of chronic insomnia in the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2003;37:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JA. The practice of pediatric sleep medicine: Results of a community survey. Pediatrics. 2001;108:e51. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.e51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JA. Epidemiology of sleep disorders during childhood. In: Sheldon SH, Ferber R, Kryger MH, editors. Principles and practices of pediatric sleep medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. pp. 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pack AI. Toward comprehensive interdisciplinary academic sleep centers. Sleep. 2007;30:383–384. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp KK, Penrod CE, Strohl KP. Knowledge and attitudes of primary care physicians toward sleep and sleep disorders. Sleep and Breathing. 2002;6:103–109. doi: 10.1007/s11325-002-0103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis ML, Giles DE, Buysse DJ, Tu X, Kupfer DJ. Self-reported sleep disturbance as a prodromal symptom in recurrent depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1997;42:209–212. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(96)01411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflugardt-Lang SA. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Milwaukee, WI: Wisconsin School of Professional Psychology; 1997. Training regarding sleep and sleep disorders: A survey of clinical psychology programs. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen R, Mahowald M, Chesson A, Doghramji K, Goldberg R, Moline M, et al. The Taskforce 2000 survey on medical education in sleep and sleep disorders. Sleep. 1998;21:235–238. doi: 10.1093/sleep/21.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen RC, Rosekind M, Rosevear C, Cole WE, Dement WC. Physician education in sleep and sleep disorders: A national survey of U.S. medical schools. Sleep. 1993;16:249–254. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen R, Zozula R. Education and training n the field of sleep medicine. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2000;6:512–518. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200011000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger E, Kushida C, Fahrenbach R, Dement W, LeBaron S. Teaching family medicine medical students about sleep disorders. Family Medicine. 2003;35:547–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifer KJ, Kruglak D, Benore E, Bellipanni K, Falk L, Halbower AC, et al. Behavioral training for increasing preschool children’s adherence with positive airway pressure: A preliminary study. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2007;5:147–175. doi: 10.1080/15402000701190671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MT, Perlis ML, Park A, Smith MS, Pennington J, Giles DE, et al. Comparative meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy for persistent insomnia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:5–11. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanski EJ, Perlis ML. A historical perspective and commentary on practical issues. In: Perlis ML, Lichstein KL, editors. Treating sleep disorders; principles and practices of behavioral sleep medicine. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2003. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Stores G, Crawford C. Medical student education in sleep and its disorders. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians in London. 1998;32:149–153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zozula R, Rosen RC, Jahn EG, Engel SH. Recognition of sleep disorders in a community-based setting following an educational intervention. Sleep Medicine. 2005;6:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]