Abstract

PURPOSE

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) degrade extracellular matrix (ECM) and increase outflow facility in anterior segment perfusion culture. One group is the ADAMTSs (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type 1 motifs). In this study, the authors examined the effects of ADAMTS-1, -4, and -5 on outflow facility and investigated their mRNA levels and protein expression in the trabecular mesh-work (TM).

METHODS

ADAMTS mRNA was quantitated by qRT-PCR in TM cells exposed to TNFα, IL-1α, TGFβ2, or mechanical stretch. ADAMTS-4 mRNA was assessed in normal and glaucomatous human anterior segments perfused at physiological or elevated pressure. Immunofluorescence was used to localize ADAMTSs in human TM cells and tissue. Anterior segments in perfusion culture were treated with recombinant ADAMTSs to determine effects on outflow facility.

RESULTS

Cytokine treatment increased mRNA of all three ADAMTSs. Mechanical stretch increased ADAMTS-4 mRNA but conversely decreased ADAMTS-1 and -5 mRNA. ADAMTS-4 mRNA levels increased in response to pressure elevation in normal eyes and to higher levels in glaucomatous eyes. ADAMTS-4 protein was highly increased in the juxtacanalicular region of the TM in anterior segments perfused at increased pressure. In human TM cells, ADAMTS-4 colocalized with cortactin in podosome- or invadopodia-like structures, but ADAMTS-1 and -5 did not. Recombinant ADAMTS-4 increased outflow facility in human and porcine anterior segments, whereas recombinant ADAMTSs-1 and -5 did not.

CONCLUSIONS

These results show differential responses and expression of ADAMTS-1, -4, and -5 in human TM cells. Combined, these results suggest that ADAMTS-4 is a potential modifier of outflow facility.

Elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) is a primary risk factor for the development of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG).1 Normal homeostatic adjustments to IOP involve remodeling extracellular matrix (ECM) in the trabecular mesh-work (TM), particularly in the juxtacanalicular (JCT) region that abuts Schlemm’s canal.2 In response to elevated IOP, certain proteinases are released by TM cells and are activated. In turn, these activated proteinases degrade selected ECM molecules, causing decreased resistance to aqueous humor outflow.3–6 Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) have been implicated in outflow resistance. Treatment of anterior segments in perfusion culture with MMPs was found to increase outflow, whereas inhibiting endogenous MMP activity by TIMP2 or synthetic MMP inhibitors reduced outflow facility.7,8 In addition, when pressures were experimentally increased in perfusion culture, there was a concomitant increase in outflow facility that coincided with increased MMP activity and ECM turnover.9 These two lines of evidence argue strongly that MMP regulation and controlled ECM turnover are major components in adjusting outflow resistance.

MMPs are a group of 23 related proteinases that are synthesized as inactive proenzymes called zymogens.10 Proteolytic removal of the prodomain releases the active enzyme, which then cleaves a wide variety of substrates including collagens, proteoglycans, cell-surface receptors, growth factors, and cytokines. 10,11 In TM cells, certain MMPs localize to specialized cellular structures termed podosome- or invadopodia-like structures (PILS).12 Targeting or compartmentalization of MMPs to such structures may increase their local concentration and focus their catalytic activity to selected substrates in the peri-cellular environment.4,13,14

Like MMPs, ADAMTSs are a group of Zn2+-dependent metalloproteinases (metzincins).15,16 ADAMTSs function in many biochemical and biological processes, including specific proteoglycan degradation, receptor ectodomain shedding, activation of cell surface receptors and growth factors, fibrillar collagen processing, and cell migration.17–19 ADAMTSs are synthesized as proenzymes and have a domain structure consisting of an N-terminal reprolysin domain and a C-terminal ancillary region.15 Perhaps the best characterized of the ADAMTSs are the aggrecanases, including ADAMTS-1, -4, and -5, which were initially shown to degrade the large chondroitin sulfate-substituted proteoglycan, aggrecan in cartilage.16,18–20

Various studies suggest that certain ADAMTSs are expressed in the TM and may be active. DNA microarray analysis of porcine TM cells in culture showed that tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin-1α (IL-1α) stimulated mRNA expression of ADAMTS-4, -5, -7, and -13.2 These cytokines are upregulated in response to laser trabeculoplasty, a common treatment to relieve IOP elevation in patients with glaucoma.21,22 Stimulation of glaucomatous TM cells with transforming growth factor β2 (TGFβ2), whose concentration increases in aqueous humor from patients with glaucoma, increased ADAMTS-5 mRNA expression. 23 A neoepitope of versican, which is exposed after ADAMTS-1 or -4 cleavage, was found to localize to PILS and to areas of the TM that experience high segmental outflow (Bradley JM, et al. IOVS 2008;49:ARVO E-Abstract 1635).12 This suggests that certain ADAMTSs, as well as MMPs, may function in ECM turnover and IOP homeostasis.

To further examine the role of ADAMTSs in the TM, we investigated ADAMTS-1, -4, and -5 mRNA expression and protein immunolocalization in cells and tissue and evaluated the effects of recombinant ADAMTSs on outflow facility in porcine and human anterior segments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

Human TM cells were dissected from donor eyes and were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-Fungizone, as described previously.24 These studies were conducted in accordance to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Cells were used between passages 3 and 5. For mechanical stretch experiments, cells were plated in cell culture inserts and placed in six-well plates. After changing to serum-free medium, cells plated on the insert membranes were mechanically stretched over a glass bead for 12, 24, or 48 hours, as described previously.9,21,25,26 For cytokine treatments, TM cells were plated in six-well plates, grown to confluence, and serum starved for 48 hours before treatment. Recombinant human TNFα (10 ng/mL; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), recombinant human IL-1α (10 ng/mL; R&D Systems),22 a combination of TNFα and IL-1α (5 ng/mL each), or recombinant TGFβ2 (5 ng/mL; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA)23 was added to serum-free cultured cells for 12, 24, or 48 hours. At the end of treatment, cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and total RNA was isolated using cells-to-cDNA cell lysis buffer (Ambion, Austin, TX). RNase was destroyed by heating to 75°C for 10 minutes, and genomic DNA was degraded by adding DNase I for 15 minutes at 37°C, which was then inactivated by heating to 75°C for 15 minutes. Samples were stored at −20°C.

To isolate RNA from TM tissue, TM was dissected from the anterior segment after perfusion and homogenized in 0.5 mL reagent (TRIzol; Invitrogen). Total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the pellet was resuspended in 20 µL diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water. Because the typical yield of RNA was low (<3 µg/TM), amplification of RNA was performed (MessageAmp II RNA amplification kit; Ambion, Austin, TX). Here, 500 ng total RNA was reverse transcribed to first-strand cDNA, and a second cDNA strand was synthesized, purified, and used as a template to synthesize amplified RNA (aRNA) in vitro according to the manufacturer’s directions. The aRNA was then purified and stored at −80°C.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA from cells (~1 µg) or aRNA from tissue (2 µL of 100 µL) was reverse transcribed to produce cDNA in a 20-µL reaction using reverse transcriptase (Superscript III; Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR was then used to quantify differences in mRNA expression of ADAMTS-1, -4, and -5 using gene-specific primers (IDT Technologies, San Diego, CA), as described previously.25,26 Briefly, 2 µL cDNA was combined with Sybr Green qPCR mix (DyNAmo HS; New England Biolabs, Ip-swich, MA) in a 20-µL reaction, and products were amplified with a thermal cycler equipped with a real-time fluorescence detector (Chromo4; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Fluorescence was read at the end of each cycle, and a melting curve was generated after the final amplification cycle. Fluorescence data were analyzed using a 6-point dilution standard curve and software (Opticon version 3; Bio-Rad). A baseline was subtracted using the average-over-the-cycle range method, and the threshold was adjusted to give a linear curve fit where r2 > 0.9. Each individual sample was analyzed in duplicate and averaged to give relative fluorescence units (RFUs). Experiments were replicated 4 to 6 times (see figure legends for n), and mean RFUs were determined for each treatment. Each sample was then normalized against 18S primers. RFUs were expressed and plotted as change multiples (e.g., treated/nontreated = x-relative quantity). Relative quantities greater than 1.5-fold and less than 0.5 were considered significant.25,26 Error bars represent the SEM.

Western Blot Analysis

Human TM cells were grown to confluence in T75-cm2 flasks and treated with cytokines (as described) for 72 hours in 5 mL serum-free media. Cells were extracted with 0.5 mL RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) containing protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM EDTA for 5 minutes on ice. Cells and ECM were scraped from the flask, and cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 12,000g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Proteins in 30 µL supernatant were separated on 10% SDS-polyacryl-amide gels (Ready gels; Bio-Rad) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were probed with an anti-C-terminal ADAMTS-4 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Millipore, Temecula, CA) and detected using a goat anti-rabbit antibody (IRDye680; Li-Cor Bio-sciences, Lincoln, NE). Membranes were scanned on an imaging system (Odyssey Infrared; Li-Cor) with companion software (Odyssey 2.0; Li-Cor).

Anterior Segment Perfusion Culture

For perfusion culture, human and porcine eyes were prepared as described previously.7,21,22,27 Human donor eye pairs were acquired from Oregon Lions Eye Bank (Portland, OR). A summary of characteristics of normal and glaucoma donor eyes used for assessing ADAMTS-4 mRNA expression are shown in Table 1. For human eyes, the time from death to culture was not more than 48 hours, and the anterior segments were placed in stationary organ culture in serum-free DMEM for 5 to 7 days to allow the recovery of cells postmortem. Porcine eyes were acquired from Carlton Packing (Carlton, OR) and were dissected within 3 hours of death. Anterior segments were then clamped into a perfusion apparatus, and serum-free DMEM was perfused at a constant pressure of 8.8 mm Hg, giving a flow rate of 1 to 7 µL/min for human eyes or 2 to 8 µL/min for porcine eyes. These rates are similar to normal physiological rates and pressures found in vivo. Eyes that could not be stabilized at these flow rates were discarded.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Information for Human Donor Eyes Used for Figure 2

| Eye ID No. | Age (y) |

Sex | Ocular History | Medications | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-0704 | 77 | F | Glaucoma | Latanoprost* | OS = control, OD = 2× |

| 2006-0747 | 81 | M | Glaucoma, IOL surgery | Latanoprost* | OS = control, OD = 2× |

| 2006-0841 | 87 | F | Glaucoma, IOL surgery 22 y.a. | Betaxolol | OD = control, OS = 2× |

| 2006-0992 | 80 | F | Unremarkable | — | OS = control, OD = 2× |

| 2006-0998 | 83 | M | Glaucoma, macular degeneration | Bimatoprost†, OS only |

OS = control, OD = 2× |

| 2007-0183 | 83 | F | Glaucoma 5–6 y, IOL surgery | ? | OD = control, OS = 2× |

| 2007-0641 | 91 | M | Unremarkable | — | OD = control, OS = 2× |

| 2007-1310 | 79 | M | Eye problems, but no specifics | — | OS = control, OD = 2× |

| 2008-0123 | 78 | F | Retinal detachment and repair, IOL surgery | — | OD = control, OS = 2× |

| 2008-0125 | 77 | M | Wore glasses | — | OS = control, OD = 2× |

| 2008-0129 | 92 | M | Glaucoma 8 y, IOL surgery 8 y.a. | Travoprost, Brimonidine‡ |

OS = control, OD = 2× |

| 2008-0182 | 77 | M | IOL surgery 1 y.a. | — | OD = control, OS = 2× |

| 2008-0242 | 87 | F | Glaucoma >10 y | Levobunolol, Brimonidine‡ |

OS = control, OD = 2× |

| 2008-0614 | 89 | M | IOL surgery 7 y.a. | — | OD = control, OS = 2× |

| 2008-0657 | 90 | M | Glaucoma, IOL surgery 15 y.a. | Latanoprost* | OS = control, OD = 2× |

| 2008-0893 | 85 | M | Glaucoma, IOL surgery | Brinzolamide§, Timolol |

OD = control, OS = 2× |

| 2008-1035 | 83 | F | Glaucoma, IOL surgery OD 8–10 y.a. | ? | OS = control, OD = 2× |

Shaded rows indicate glaucoma eyes. y.a., Years ago; 2×, anterior segments subject to 2× elevated pressure in perfusion culture.

Xalatan; Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY.

Lumigan; Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA.

Alphagan; Allergan, Inc.

Azopt; Allergan, Inc.

After approximately 24 hours of stable flow rates, treatments were initiated. For human eyes that were subject to elevated pressure, one eye of each pair was subject to double the pressure (~16 mm Hg), which increased the flow rate to approximately 12 to 15 µL for another 24 hours (for RNA isolation experiments) or 48 hours (for protein immunolocalization experiments). For ADAMTS treatments, recombinant ADAMTSs (Millipore) were applied by direct in-line injection of the enzyme into the intake flow tube. One microgram or 0.5 µg recombinant ADAMTS-4 (Millipore; specific activity 3.7 nmol hydrolyzed substrate/min/mg ADAMTS-4) was placed in 100 µL buffer containing 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM CaCl2. Control eyes were injected with buffer alone. One microgram recombinant ADAMTS-5 (specific activity, 5 nmol hydrolyzed substrate/min/mg ADAMTS-5) and 2 µg ADAMTS-1 (specific activity, 1.4 nmol hydrolyzed substrate/min/mg ADAMTS-1) were also tested. Serum-free media were perfused for another 24 to 48 hours.

Outflow rates were plotted as time (hours) versus normalized flow rate. For each eye, the flow rates before the start of treatment (−30 to 0 hours) were averaged to provide a baseline flow rate. Actual flow rates of each eye were then divided by this baseline flow rate to generate a “normalized” flow rate.22,27,28 Data from individual experiments were then combined and averaged, and the SEM was calculated. Time point 0 represents the start of treatment. The number of eyes used for each treatment is noted in each figure legend. A paired Student’s t-test or a Mann-Whitney ranked sum test was performed to determine significance. P <0.05 was considered significant.

Immunostaining and Confocal Microscopy

Human TM cells were plated into collagen type I-coated membranes (Bioflex; Flexcell, Hillsborough, NC) in six-well plates and were grown for 48 hours.12 Membranes were removed from the plate with a scalpel and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5 minutes. Immunostaining of deparaffinized tissue sections and cells plated on membranes was performed, as described previously.12,27 All slides were blocked with 2% normal goat serum in PBS before the addition of primary antibodies diluted in PBS. Primary antibodies used were as follows: rabbit polyclonal anti-ADAMTS-4 C-terminus (Millipore or Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit polyclonal anti-ADAMTS-5 C-terminus (Millipore), rabbit polyclonal anti-ADAMTS-1 C-terminus (Abcam), monoclonal anti-cortactin (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), and monoclonal anti-versican (Kamiya Biomedical, Seattle, WA). Negative controls substituting PBS for the primary antibody were also performed. Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 488 nm-conjugated goat anti-mouse and Alexa Fluor 594 nm-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Coverslips were mounted with gold mounting medium (Prolong; Molecular Probes), which contains the DNA-binding dye 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

Anterior segments were removed from the flow chambers, and the tissue was immediately fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for at least 24 hours, as described previously.12,27 Eyes were cut into approximately 8 to 10 wedges, each of which was embedded into a single paraffin block, and 5-µm serial radial sections were cut approximately perpendicular to Schlemm’s canal at the pathology/histology core facility of the Knight Cancer Institute (Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR). Thus, each paraffin section contained tissue from 8 to 10 regions around the eye. At least three eyes per treatment were analyzed. After deparaffinization and hydration, immunostaining was performed as above. At least five sections for each antibody were evaluated by immunofluorescence.

Tissue sections and randomly selected fields from collagen type I-coated membranes (Bioflex; Flexcell) were visualized and imaged by confocal microscopy (Fluoview 1000; Olympus, San Diego, CA). Each channel was scanned sequentially to maximize separation of colors. Confocal images were processed using either Olympus software (Fluoview FV1000) or ImageJ software (developed by Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/index.html).

RESULTS

mRNA Levels in Cytokine-Treated TM Cells

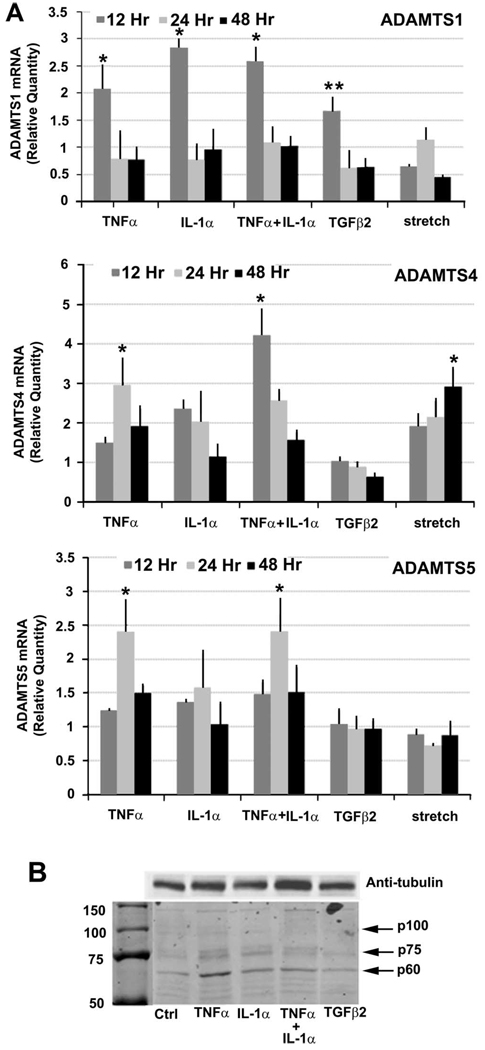

Various treatments were used to assess ADAMTS-1, -4, and -5 mRNA levels in TM cells (Fig. 1A). The cytokines TNFα and IL-1α are induced by laser trabeculoplasty, and both increase outflow facility in human anterior segments.7,21,22 Concentrations of TGFβ2 are increased in the aqueous humor of patients with glaucoma, and TGFβ2 decreases outflow facility in perfusion culture.29–31 Thus, TNFα/IL-1α and TGFβ2 seem to induce opposite effects in TM cells. ADAMTS mRNA expression was also investigated in response to mechanical stretch because TM cells likely sense increased IOP as a mechanical stretch via integrins or other cell-surface receptors.2,6,9,25,32

FIGURE 1.

(A) ADAMTS mRNA levels in TM cells in response to various treatments. Quantitative RT-PCR of ADAMTS-1 (top), ADAMTS-4 (middle), and ADAMTS-5 (bottom) mRNA levels in human TM cells treated with TNFα, IL-1α, their combination, TGFβ2, or mechanical stretch for 12, 24, or 48 hours. Data were normalized to 18S. For ADAMTS-1, n = 4 for all treatments apart from stretch, where n = 6; for ADAMTS-4, n = 5 for all treatments apart from stretch, where n = 6; for ADAMTS-5, n = 5 for all treatments apart from stretch, where n = 6. *P = 0.03; **P = 0.04. Error bars, SEM. (B) Western immunoblotting of RIPA TM cells lysates using a C-terminal ADAMTS-4 polyclonal antibody. Cells were treated for 72 hours in serum-free media with the cytokines indicated. Various species were identified: p100 represents the full-length protein, p75 is ADAMTS-4 after furin proteolytic removal of the N-propeptide, and p60 represents a form that has its N-propeptide and a portion of its C-terminal removed. Other bands remain unidentified at this time. Antitubulin was run as a loading control. Molecular weight markers sizes are shown in kDa.

ADAMTS-1 mRNA was increased approximately 2.5-fold in response to TNFα, IL-1α, or their combination and by 1.5-fold for TGFβ2 at 12 hours, but not at other time points. Mechanical stretch did not significantly affect ADAMTS-1 mRNA. TNFα increased ADAMTS-4 mRNA levels approximately 1.5-, 3-, and 1.9-fold at 12, 24, and 48 hours, respectively. IL-1α also increased ADAMTS-4 mRNA approximately 2-fold at 12 and 24 hours, whereas the combination of TNFα and IL-1α seemed to have a synergistic effect at 12 hours, inducing a 4-fold increase in mRNA levels. TGFβ2 did not significantly affect ADAMTS-4 mRNA. Mechanical stretch increased ADAMTS-4 mRNA over time, from 1.9-fold at 12 hours to 3-fold at 48 hours. ADAMTS-5 mRNA was increased by TNFα and a combination of TNFα and IL-1α by 2.5-fold at 24 hours only. Neither TGFβ2 nor mechanical stretch significantly affected ADAMTS-5 mRNA levels. In untreated TM cells and tissues, relative mRNA levels of ADAMTS were ADAMTS-4>ADAMTS-5>ADAMTS-1 (data not shown).

To investigate whether ADAMTS-4 protein levels were also increased after cytokine treatment of human TM cells, Western blot analysis of RIPA cell lysates was performed (Fig. 1b). Multiple species of ADAMTS-4 were found, consistent with previous reports of proteolytic processing of the ADAMTS-4 C-terminal ancillary region.33–35 Full-length ADAMTS-4 (p100) and two other species (p75 and p60) that represented active ADAMTS-4 were detected using a C-terminal antibody (Fig. 1b). The p75 form represented ADAMTS-4 after furin proteolytic removal of the N-propeptide, and p60 is a form that has its N-propeptide and a portion of its C-terminal removed. Levels of the p100 form were difficult to detect because presumably the N-propeptide is cleaved relatively quickly during secretion. Other bands were also detected, but their identities are unknown. The cleaved N-propeptide was detected in the media using an N-terminal-specific antibody (data not shown). Protein levels for human TM cells treated with TNFα, IL-1α, and the combination of TNFα and IL-1α were consistently higher than the untreated control and TGF-β2-treated lanes.

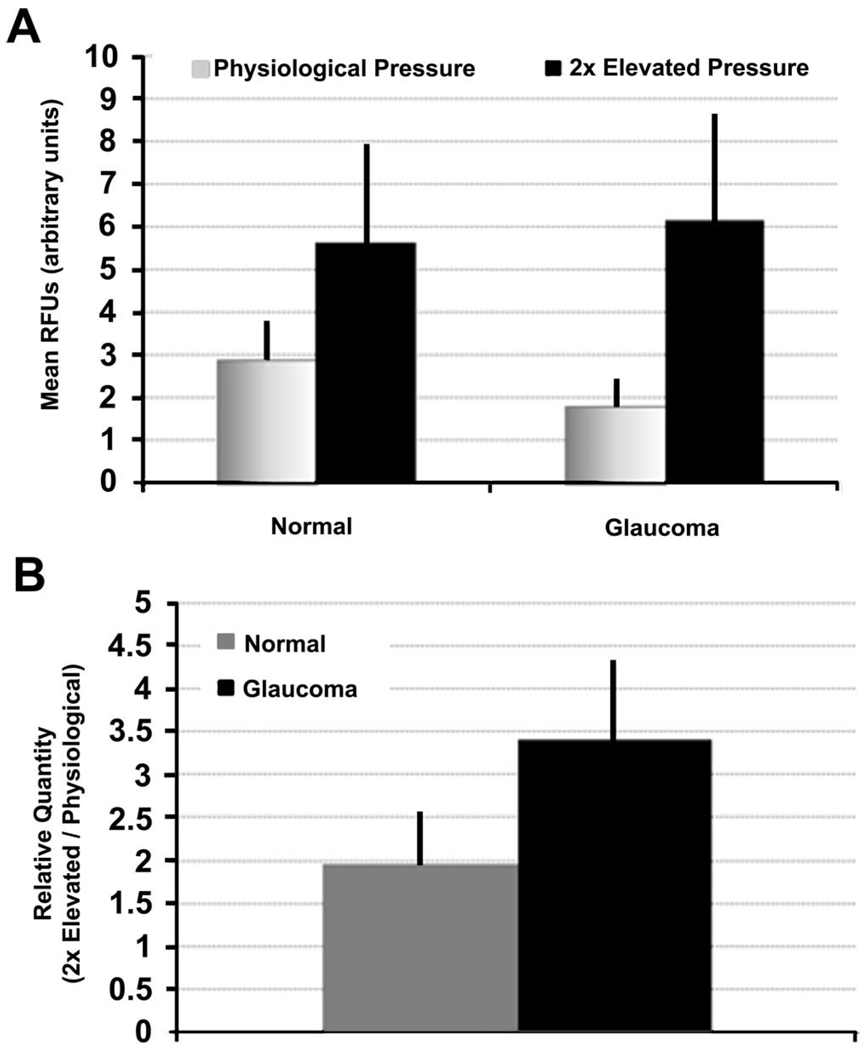

ADAMTS-4 mRNA Expression in Perfused Anterior Segments

Given that ADAMTS-4 mRNA was found to increase when TM cells in culture were subject to mechanical stretching (Fig. 1), we also investigated whether ADAMTS-4 mRNA was altered when human anterior segments were subject to increased pressure in perfusion culture. These responses were compared between glaucoma donor eyes and control eyes with no history of glaucoma (normal; Table 1). For each eye pair, one anterior segment was perfused at physiological pressure, whereas the contralateral eye was subject to 2× elevated pressure for 24 hours. ADAMTS-4 mRNA was generally higher in control eyes from healthy subjects than in glaucoma donor eyes (Fig. 2A). In anterior segments subject to elevated pressure, ADAMTS-4 mRNA levels were similar between normal and glaucomatous anterior segments. When expressed as a ratio, increased pressure caused a 2-fold increase in ADAMTS-4 mRNA in normal eyes and a 3.4-fold increase in glaucoma eyes (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

ADAMTS-4 mRNA levels in perfused human eyes at physiological or elevated pressure. (A) Comparison of ADAMTS-4 levels in normal and glaucoma anterior segments perfused at physiological or 2× elevated pressure for 24 hours. mRNA levels were quantitated by qRT-PCR and normalized to 18S, and RFUs were calculated. (B) Data were calculated as relative quantities (2×/physiological) for each pair of eyes and values from each pair were averaged. n = 7 for normal and n = 10 for glaucoma anterior segments. Error bars, SEM.

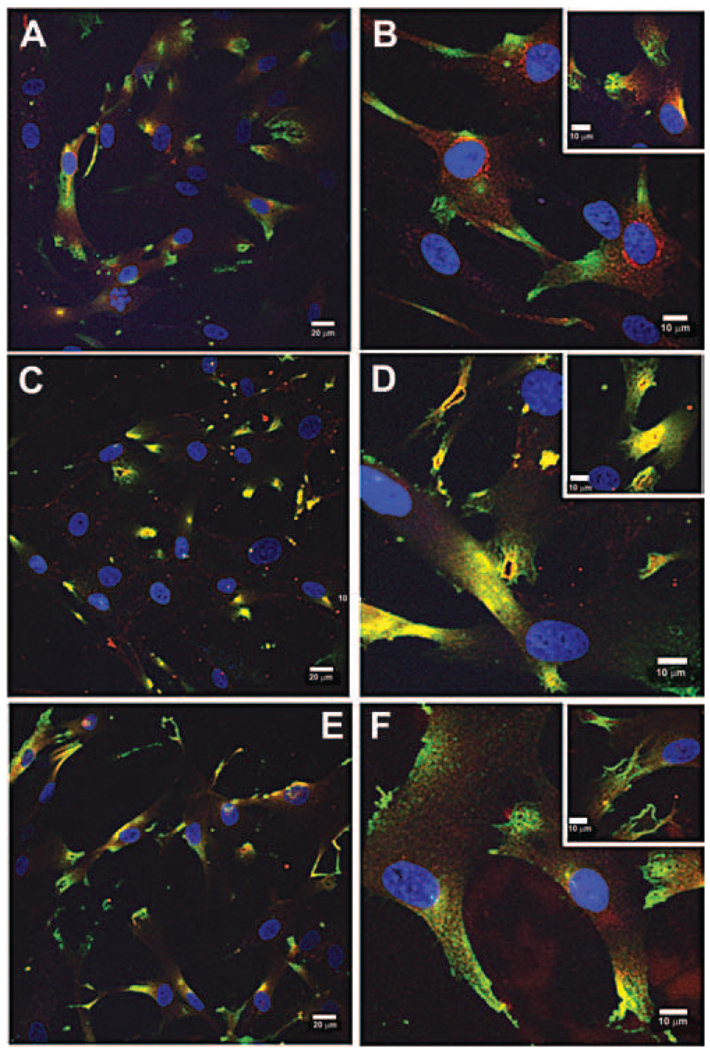

Immunostaining of ADAMTSs in Human TM Cells

To determine the immunolocalization of ADAMTSs in human TM cells, double immunolabeling experiments using cortactin and ADAMTS-1, -4, or -5 antibodies were performed. Cortactin is a marker of PILS.12

Double-immunolabeling experiments showed that ADAMTS-4 (red) colocalized with cortactin (green) at PILS (yellow colocalization; Figs. 3C, D). ADAMTS-4 was present in typical rhomboid-shaped PILS and in other PILS structures, including rosettes. In nearly all PILS that were present, as defined by positive cortactin immunostaining, ADAMTS-4 was colocalized. Conversely, ADAMTS-1 and ADAMTS-5 staining patterns were different and were generally much diminished compared with ADAMTS-4 immunostaining. ADAMTS-1 immunostaining was localized within the cytoplasm, especially in the perinuclear region (Figs. 3A, B). There was little or no colocalization with cortactin at PILS. ADAMTS-5 staining was also present as a diffuse pattern localized in the cytoplasm (Figs. 3E, F). There was little colocalization with cortactin in rhomboid-shaped PILS or in rosette structures. However, there did seem to be a small amount of colocalization with cortactin in thin lines of staining at the cell surface (Fig. 3E).

FIGURE 3.

ADAMTS localization in human TM cells grown on collagen-coated membranes for 24 hours. (A, B) Double-labeling of cortactin (green) and ADAMTS-1 (red). (C, D) Double-labeling of cortactin (green) and ADAMTS-4 (red). Colocalization at PILS (orange/yellow). (E, F) Double-labeling of cortactin (green) and ADAMTS-5 (red). DAPI was used to stain nuclei (blue). Scale bars: 20 µm (A, C, E); 10 µm (B, D, F, and all insets).

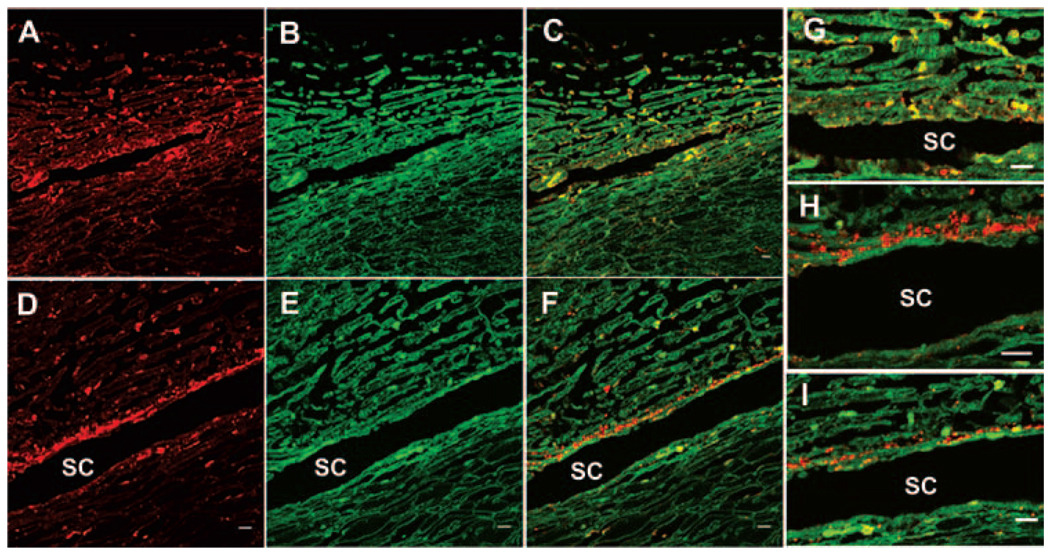

Immunostaining of ADAMTS-4 in Human TM

To investigate the protein distribution in human TM tissue, anterior segments were perfused at physiological pressure for 48 hours, then fixed, and immunostaining was performed. A versican antibody was also used because versican is abundantly expressed in the TM and is a target for ADAMTS-4 cleavage. 26,36,37 ADAMTS-4 (red) was found in a somewhat patchy expression pattern in the TM, with some staining present in the JCT region (Fig. 4A). Colocalization with versican (green; Fig. 4B) showed that much of the ADAMTS-4 staining was coincident with versican (yellow; Fig. 4C). At higher magnification, an image of the JCT region shows frequent colocalization of ADAMTS-4 and versican immunostaining (yellow), although there was a small amount of ADAMTS-4 alone detected (red; Fig. 4G).

FIGURE 4.

ADAMTS-4 immunolocalization in human TM. Human anterior segments were perfused at physiological IOP (A–C, G), and the contralateral eye was perfused at 2× pressure (D–F, H, I) for 48 hours. Colocalization (yellow) of ADAMTS-4 antibody (red) and versican (green) antibody. SC, Schlemm’s canal. Scale bar, 10 µm.

Because the mRNA results suggested that ADAMTS-4 mRNA was upregulated in response to mechanical stretch (Fig. 1), ADAMTS-4 protein distribution was also investigated in the contralateral eye that was perfused at elevated pressure (2×) for 48 hours. A different pattern of ADAMTS-4 immunostaining was observed (Figs. 4D–F, H, I). In these eyes, a thin strip of ADAMTS-4 staining (red) was highly increased in the JCT region, which ran parallel to the entire length of Schlemm’s canal (Fig. 4D). This immunostaining was generally not coincident with versican (green; Fig. 4E), but a small amount of patchy staining in the outer beams of the TM did colocalize with versican (Fig. 4F). Higher magnification images showed that ADAMTS-4 expression in the JCT typically did not colocalize with versican (Figs. 4H, I).

Recombinant ADAMTS Treatment of Anterior Segments in Perfusion Culture

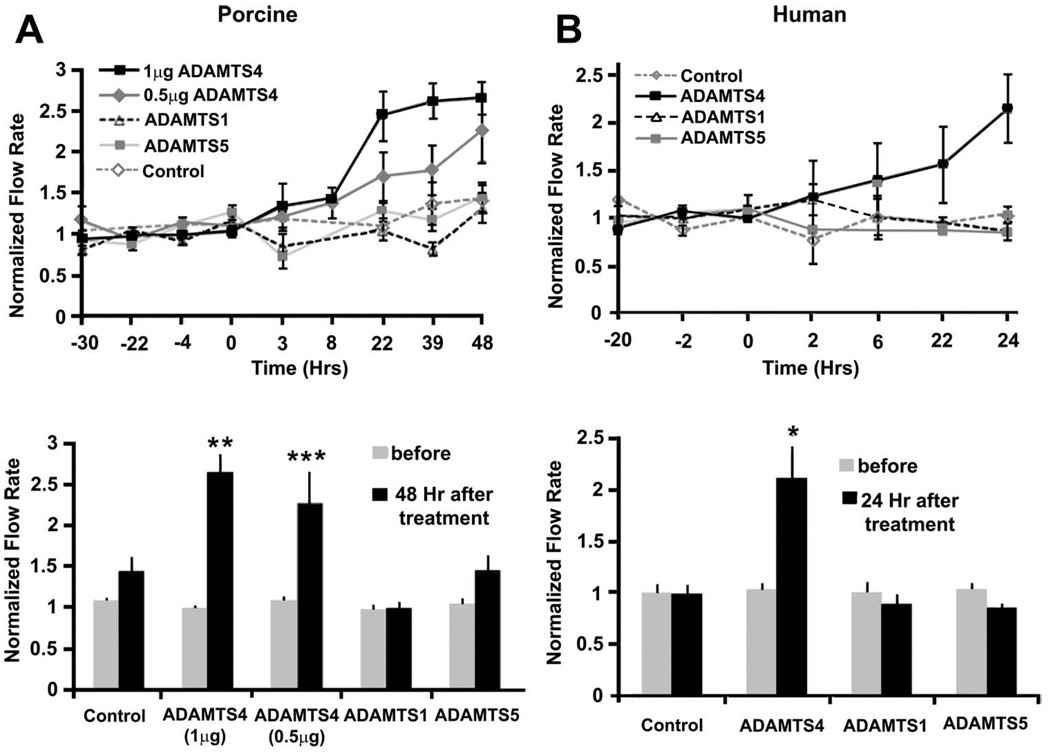

To test the effects of ADAMTSs on outflow facility, recombinant ADAMTSs were added to anterior segments in perfusion culture (Fig. 5). In porcine anterior segments, ADAMTS-4 (1 µg) was found to increase outflow facility approximately 2.6-fold in 48 hours, whereas 0.5 µg increased outflow 2.2-fold (Fig. 5A). These increases were significant (P = 0.0089 and P = 0.0497, respectively) when compared with average flow before treatment (Fig. 5A). There was no significant increase in normalized flow rate in response to ADAMTS-1 or ADAMTS-5 treatment. This experiment was repeated using human anterior segments (Fig. 5B). One microgram ADAMTS-4 increased outflow facility of human eyes (n = 3) approximately 2.1-fold over 24 hours (Fig. 5B). Comparable concentrations of ADAMTS-1 or ADAMTS-5 did not show similar increases in outflow facility. The increase in outflow facility was significant (P = 0.0438) when compared with the average flow before treatment. Together these results suggest that ADAMTS-4, but not ADAMTS-1 or -5, increased outflow facility in human and porcine anterior segments.

FIGURE 5.

Recombinant ADAMTS treatment of (A) porcine or (B) human anterior segments in perfusion culture. One microgram or 0.5µg recombinant ADAMTS-4, 1 µg ADAMTS-5, or 2 µg ADAMTS-1 was applied at time point 0, and outflow facility was monitored for a further 24 to 48 hours. Error bars represent the SEM; n = 3 for all human treatments; n = 6 for all porcine treatments, except ADAMTS-5, where n = 7. Facility data are also expressed as normalized flow rates before and either 24 or 48 hours after treatment. *P = 0.0438, **P = 0.0089, and ***P = 0.0497 as calculated by a paired Student’s t-test compared with average flow rate before treatment.

DISCUSSION

ADAMTS-1, -4, and -5 show a high degree of sequence homology and have overlapping functions, at least in terms of aggrecanolysis and cartilage degradation.33 Here, however, differential effects of ADAMTS-1, -4, and -5 are shown in mRNA levels and protein expression patterns in TM cells and in outflow facility responses to treatment with recombinant protein. ADAMTS-4 mRNA levels increased in response to mechanical stretch, whereas ADAMTS-1 and -5 mRNA did not change significantly (Fig. 1A). ADAMTS-4 localized to PILS structures in human TM cells, but ADAMTS-1 and -5 did not (Fig. 3). Recombinant ADAMTS-4 increased outflow facility in both human and porcine anterior segments in perfusion culture, but recombinant ADAMTS-1 and -5 had minimal effects (Fig. 5). These differential effects suggest that ADAMTS-4 may perform functions different from those of ADAMTS-1 or -5 in TM cells and may be an important regulator of outflow facility.

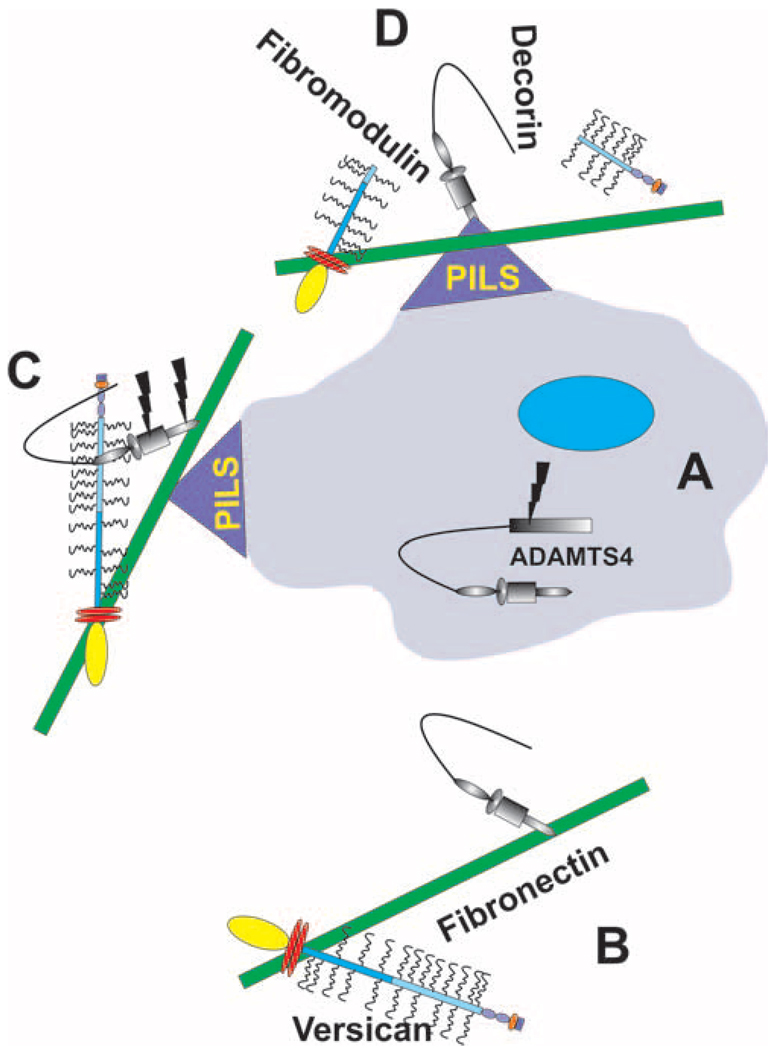

ADAMTS-4 has numerous proteolytic substrates, including versican, aggrecan, brevican, decorin, fibromodulin, and carboxymethylated transferrin.16,38 ADAMTS-1 also cleaves versican, 36 but there are no reports that ADAMTS-5 has similar versicanase activity. In the TM, aggrecan is not present in appreciable amounts2,39; therefore, these other proteins must represent the major proteolytic targets in the TM. Versican is of particular interest. This is a large CS-substituted proteoglycan that interacts with many other ECM molecules, including hyaluronan, CD44, fibrillins-1 and -2, tenascin C, and fibronectin. Thus, versican serves as an attractive prospect as a major component of the outflow resistance.2 Versican is composed of two central GAG-binding domains, termed αGAG and βGAG, that can be included or excluded from the protein isoform by alternative mRNA splicing.40 This gives four splice forms termed V0, V1, V2, and V3. The V1 isoform is the major splice variant expressed by TM cells,26,37 and it contains the αGAG domain, which includes the ADAMTS-1/4 protease-sensitive site.36 Decorin and fibromodulin are both present in TM, and their mRNA levels are affected by various treatments of TM cells in culture; for example, fibromodulin mRNA is increased by mechanical stretch.2,25 These proteoglycans are members of the small, leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs) and function to limit the lateral growth of collagen fibrils.41 Brevican, like versican, is also a CS-substituted proteoglycan, but its expression is mostly limited to the central nervous system.42 Therefore, of the ADAMTS-4 substrates present in the TM, versican, decorin, and fibromodulin are the most likely candidates for contributing to the outflow resistance. In addition, of all the aggrecanases, ADAMTS-4 shows the highest activity on substrates other than aggrecan.33 This may help explain why ADAMTS-4 increased outflow facility while ADAMTSs -1 and -5 had little effect.

Similar to certain MMPs, ADAMTS-4 is an enzyme that degrades ECM, increases outflow facility, and localizes to PILS. However, unlike MMPs, which tend to be localized throughout the TM, ADAMTS-4 expression increases specifically in the JCT region of the TM in response to elevated pressure (Fig. 4). Moreover, MMPs have a larger number of known substrates than ADAMTSs. This makes ADAMTSs a more attractive target for the development of new therapies for patients with POAG. However, the mechanisms by which ADAMTS-4 increases outflow facility remain unknown. Certainly, one can envision that if versican, decorin, or fibromodulin are proteolytically cleaved by ADAMTS-4, the structural integrity of the matrix is compromised, thereby allowing greater outflow of aqueous humor. Because versican interacts with many other ECM molecules, its cleavage likely leads to a major disruption of ECM interactions. Secondary effects may then occur, such as penetration of MMPs into regions that are usually inaccessible to MMP cleavage. 4 In this regard, SLRPs, the family of proteoglycans to which decorin and fibromodulin belong, protect collagen fibrils from degradation by MMP-1 and MMP-13.43 Therefore, ADAMTS-4 cleavage of decorin, fibromodulin, or both may indirectly induce MMP cleavage of collagen fibrils, especially since activities of MMPs -1 and -13 are increased by similar manipulations as ADAMTS-4 (e.g., TNFα, IL-1α, and mechanical stretch).2,4,8,44

The immunostaining pattern of ADAMTS-4 in human eyes was particularly intriguing. In eyes that were perfused at physiological pressure, there was patchy expression of ADAMTS-4 throughout the TM beams that was coincident with versican staining (Fig. 4). This colocalization may represent the congruence of ADAMTS-4 and versican at PILS located in the outer TM beams but before the cleavage of versican. Therefore, this pattern of expression may represent a portion of ADAMTS-4 that functions in normal ECM turnover; it was also observed in the outer beams of eyes subject to elevated pressure (Fig. 4). However, there was an additional pattern of immunostaining in eyes subject to elevated pressure; ADAMTS-4 was highly expressed in the JCT, in a thin strip running parallel to Schlemm’s canal. This ADAMTS-4 expression was exactly where one would expect a proteinase to be expressed if it were to function as a modifier of outflow resistance. This immunostaining was generally not coincident with versican staining, even though versican was present in the JCT region. The most likely explanation would be that ADAMTS-4 has cleaved versican and, therefore, that these molecules no longer colocalize. In addition, it suggests that in response to elevated pressure, ADAMTS-4 expressed in the JCT region contributes to ECM turnover and outflow resistance modification so that physiological IOP can be restored.

The activation of ADAMTS-4 is complex, and a model of ADAMTS-4 secretion and activation is proposed based on the literature and the observations presented here (Fig. 6). The N-propeptide is removed by furin-cleavage in the secretory pathway,15 and ADAMTS-4 is then secreted into the ECM, where the spacer domain interacts with the C-terminal domain of fibronectin.45 This interaction renders ADAMTS-4 inactive and sequesters it in the ECM. Fibronectin also binds the C-terminal domain of versican, and both are localized at PILS.46 Therefore, fibronectin may be involved in targeting both the enzyme (ADAMTS-4) and the substrate (versican) to the specific cellular location (PILS) where enzyme activation can occur. Activation of ADAMTS-4 involves proteolytic removal of the C-terminal spacer domain, which we propose may occur at PILS. MT4-MMP (MMP-17) may be involved in activation, but autocatalytic activity that cleaves the ADAMTS-4 spacer domain or Cys-rich domain has also been detected.34,35 Certainly, multiple ADAMTS-4 species are detected by Western blot analysis of TM cell lysates (Fig. 1B), the sizes of which are consistent with previously reported proteolytically cleaved forms of ADAMTS-4. Further studies are, therefore, required to identify the MMP responsible for activating ADAMTS-4 at PILS. Only after proteolytic cleavage of the inhibitory spacer domain is active ADAMTS-4 released to cleave its substrates. Removal also greatly enhances ADAMTS-4 proteolytic activity against nonaggrecan substrates (e.g., versican, decorin, and fibromodulin). 33,38 Localization at PILS may aid in targeting ADAMTS-4 proteolytic activity to versican. Certainly, an ADAMTS-cleaved neo-epitope of versican is localized at PILS.12 This was likely cleaved by ADAMTS-4 because ADAMTS-1 was not colocalized with cortactin at PILS (Fig. 3). Therefore, activation of ADAMTS-4 may generate a more promiscuous enzyme with destructive abilities that is capable of disaggregating ECM-GAG interactions within the TM.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic of a proposed model of secretion and activation of ADAMTS-4 in TM cells. (A) ADAMTS-4 is synthesized and, after proteolytic removal of the N-propeptide by furin, secreted into the ECM. (B) In the ECM, the ADAMTS-4 spacer domain binds to the C-terminal region of fibronectin, which also binds versican. Fibronectin may be involved in targeting both the enzyme and the substrate to PILS because all three proteins localize at these cellular structures (C). Proteolytic removal of ADAMTS-4 spacer domain activates the enzyme, and it then cleaves its substrates (e.g., versican, decorin, and fibromodulin) (D).

There is some debate about whether ADAMTSs are differently regulated in normal and diseased tissues. In some studies, ADAMTS-4 levels were higher than those of ADAMTS-5 in osteoarthritic (OA) cartilage, but other reports suggest the opposite.47–49 In knockout mouse models of OA, deletion of ADAMTS-5 protected joints from cartilage destruction when OA was surgically induced, whereas ablation of ADAMTS-4 did not.47,50,51 Again, this suggests differential effects of ADAMTSs in tissue. Here, we show that normal TM tissue has a higher level of ADAMTS-4 mRNA than glaucoma TM tissue (Fig. 2). When the TM is subject to increased pressure, TM cells respond by increasing ADAMTS-4 mRNA levels in both diseased and nondiseased tissues. This was consistent with the increase in mRNA induced by mechanical stretch of TM cells in culture (Fig. 1A). However, glaucomatous TM cells produced a much greater response (3.4-fold) than normal TM cells (2-fold), suggesting that glaucoma TM cells synthesize more ADAMTS-4 than normal tissues when attempting to correct outflow resistance. Differences between normal and glaucoma TM cells may also explain TM cell responses to TGFβ2 treatment. TGFβ2 increased ADAMTS-5 mRNA levels in glaucomatous TM cells,23 but there was little effect of TGFβ2 on ADAMTS-5 mRNA in normal TM cells (Fig. 1A). Therefore, in response to elevated IOP or increased TGFβ2 concentrations in the aqueous humor, glaucoma TM cells may overstimulate the synthesis of ADAMTS-4 or -5, or both.

In summary, ADAMTS-4 is another Zn2+-dependent metalloproteinase that increases outflow facility in vitro. It is expressed strongly in the JCT region of the TM when anterior segments are subject to increased pressure. More studies are required to identify the substrate(s) of ADAMTS-4 in the TM, as part of our overall goal, of identifying ECM components that are the source of the outflow resistance in the TM.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ruth Phinney (Lions Eye Bank, Portland, OR) for facilitating the procurement of human eyes, Carolyn Gendron (Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health and Science University) for paraffin sectioning and histology, and Genevieve Long for editorial assistance.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY003279, EY008247, and EY010572 (TSA); Collins Medical Trust (KEK); Glaucoma Research Foundation Shaffer grant (KEK); and an unrestricted grant to the Casey Eye Institute from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Footnotes

Disclosure: K. Keller, None; J. Bradley, None; T.S. Acott, None

References

- 1.Boland MV, Quigley HA. Risk factors and open-angle glaucoma: classification and application. J Glaucoma. 2007;16:406–418. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31806540a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acott TS, Kelley MJ. Extracellular matrix in the trabecular meshwork. Exp Eye Res. 2008;86:543–561. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander JP, Samples JR, Van Buskirk EM, Acott TS. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and inhibitor by human trabecular meshwork. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:172–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keller KE, Aga M, Bradley JM, Kelley MJ, Acott TS. Extracellular matrix turnover and outflow resistance. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:676–682. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borras T. Gene expression in the trabecular meshwork and the influence of intraocular pressure. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003;22:435–463. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(03)00018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WuDunn D. The effect of mechanical strain on matrix metalloproteinase production by bovine trabecular meshwork cells. Curr Eye Res. 2001;22:394–397. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.22.5.394.5500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley JM, Vranka J, Colvis CM, et al. Effect of matrix metalloproteinases activity on outflow in perfused human organ culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:2649–2658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexander JP, Samples JR, Acott TS. Growth factor and cytokine modulation of trabecular meshwork matrix metalloproteinase and TIMP expression. Curr Eye Res. 1998;17:276–285. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.17.3.276.5219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley JM, Kelley MJ, Zhu X, Anderssohn AM, Alexander JP, Acott TS. Effects of mechanical stretching on trabecular matrix metalloproteinases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1505–1513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakraborti S, Mandal M, Das S, Mandal A, Chakraborti T. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinases: an overview. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;253:269–285. doi: 10.1023/a:1026028303196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page-McCaw A, Ewald AJ, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:221–233. doi: 10.1038/nrm2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aga M, Bradley JM, Keller KE, Kelley MJ, Acott TS. Specialized podosome- or invadopodia-like structures (PILS) for focal trabecular meshwork extracellular matrix turnover. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5353–5365. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ra HJ, Parks WC. Control of matrix metalloproteinase catalytic activity. Matrix Biol. 2007;26:587–596. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen WT, Wang JY. Specialized surface protrusions of invasive cells, invadopodia and lamellipodia, have differential MT1-MMP, MMP-2, and TIMP-2 localization. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;878:361–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apte SS. A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease (reprolysin type) with thrombospondin type 1 motifs: the ADAMTS family. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:981–985. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porter S, Clark IM, Kevorkian L, Edwards DR. The ADAMTS metalloproteinases. Biochem J. 2005;386:15–27. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang BL. ADAMTS: a novel family of extracellular matrix proteases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(00)00061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones GC, Riley GP. ADAMTS proteinases: a multi-domain, multi-functional family with roles in extracellular matrix turnover and arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:160–169. doi: 10.1186/ar1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagase H, Kashiwagi M. Aggrecanases and cartilage matrix degradation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:94–103. doi: 10.1186/ar630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bondeson J, Wainwright S, Hughes C, Caterson B. The regulation of the ADAMTS4 and ADAMTS5 aggrecanases in osteoarthritis: a review. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley JM, Anderssohn AM, Colvis CM, et al. Mediation of laser trabeculoplasty-induced matrix metalloproteinase expression by IL-1β and TNFα. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:422–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelley MJ, Rose AY, Song K, et al. Synergism of TNF and IL-1 in the induction of matrix metalloproteinase-3 in trabecular meshwork. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2634–2643. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleenor DL, Shepard AR, Hellberg PE, Jacobson N, Pang IH, Clark AF. TGFβ2-induced changes in human trabecular meshwork: implications for intraocular pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:226–234. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polansky JR, Weinreb RN, Baxter JD, Alvarado J. Human trabecular cells, I: Establishment in tissue culture and growth characteristics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1979;18:1043–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vittal V, Rose A, Gregory KE, Kelley MJ, Acott TS. Changes in gene expression by trabecular meshwork cells in response to mechanical stretching. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2857–2868. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller KE, Kelley MJ, Acott TS. Extracellular matrix gene alternative splicing by trabecular meshwork cells in response to mechanical stretching. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1164–1172. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keller KE, Bradley JM, Kelley MJ, Acott TS. Effects of modifiers of glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis on outflow facility in perfusion culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2495–2505. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bachmann B, Birke M, Kook D, Eichhorn M, Lutjen-Drecoll E. Ultrastructural and biochemical evaluation of the porcine anterior chamber perfusion model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2011–2020. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inatani M, Tanihara H, Katsuta H, Honjo M, Kido N, Honda Y. Transforming growth factor-beta 2 levels in aqueous humor of glaucomatous eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001;239:109–113. doi: 10.1007/s004170000241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gottanka J, Chan D, Eichhorn M, Lutjen-Drecoll E, Ethier CR. Effects of TGF-beta2 in perfused human eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:153–158. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tripathi RC, Li J, Chan WF, Tripathi BJ. Aqueous humor in glaucomatous eyes contains an increased level of TGF-beta 2. Exp Eye Res. 1994;59:723–727. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tumminia SJ, Mitton KP, Arora J, Zelenka P, Epstein DL, Russell P. Mechanical stretch alters the actin cytoskeletal network and signal transduction in human trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:1361–1371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao G, Westling J, Thompson VP, Howell TD, Gottschall PE, Sandy JD. Activation of the proteolytic activity of ADAMTS4 (aggrecanase-1) by C-terminal truncation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11034–11041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107443200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao G, Plaas A, Thompson VP, Jin S, Zuo F, Sandy JD. ADAMTS4 (aggrecanase-1) activation on the cell surface involves C-terminal cleavage by glycosylphosphatidyl inositol-anchored membrane type 4-matrix metalloproteinase and binding of the activated proteinase to chondroitin sulfate and heparan sulfate on syndecan-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10042–10051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flannery CR, Zeng W, Corcoran C, et al. Autocatalytic cleavage of ADAMTS-4 (Aggrecanase-1) reveals multiple glycosaminoglycan-binding sites. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42775–42780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205309200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandy JD, Westling J, Kenagy RD, et al. Versican V1 proteolysis in human aorta in vivo occurs at the Glu441-Ala442 bond, a site that is cleaved by recombinant ADAMTS-1 and ADAMTS-4. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13372–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao X, Russell P. Versican splice variants in human trabecular meshwork and ciliary muscle. Mol Vis. 2005;11:603–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fushimi K, Troeberg L, Nakamura H, Lim NH, Nagase H. Functional differences of the catalytic and non-catalytic domains in human ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 in aggrecanolytic activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6706–6716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708647200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wirtz MK, Bradley JM, Xu H, et al. Proteoglycan expression by human trabecular meshworks. Curr Eye Res. 1997;16:412–421. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.16.5.412.7040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wight TN. Versican: a versatile extracellular matrix proteoglycan in cell biology. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:617–623. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00375-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hocking AM, Shinomura T, McQuillan DJ. Leucine-rich repeat glycol-proteins of the extracellular matrix. Matrix Biol. 1998;17:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamaguchi Y. Lecticans: organizers of the brain extracellular matrix. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:276–289. doi: 10.1007/PL00000690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geng Y, McQuillan D, Roughley PJ. SLRP interaction can protect collagen fibrils from cleavage by collagenases. Matrix Biol. 2006;25:484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.08.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samples JR, Alexander JP, Acott TS. Regulation of the levels of human trabecular matrix metalloproteinases and inhibitor by interleukin-1 and dexamethasone. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:3386–3395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hashimoto G, Shimoda M, Okada Y. ADAMTS4 (aggrecanase-1) interaction with the C-terminal domain of fibronectin inhibits proteolysis of aggrecan. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32483–32491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamagata M, Yamada KM, Yoneda M, Suzuki S, Kimata K. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (PG-M-like proteoglycan) is involved in the binding of hyaluronic acid to cellular fibronectin. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13526–13535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stanton H, Rogerson FM, East CJ, et al. ADAMTS5 is the major aggrecanase in mouse cartilage in vivo and in vitro. Nature. 2005;434:648–652. doi: 10.1038/nature03417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bau B, Gebhard PM, Haag J, Knorr T, Bartnik E, Aigner T. Relative messenger RNA expression profiling of collagenases and aggrecanases in human articular chondrocytes in vivo and in vitro. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2648–2657. doi: 10.1002/art.10531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kevorkian L, Young DA, Darrah C, et al. Expression profiling of metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:131–141. doi: 10.1002/art.11433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glasson SS, Askew R, Sheppard B, et al. Deletion of active ADAMTS5 prevents cartilage degradation in a murine model of osteoarthritis. Nature. 2005;434:644–648. doi: 10.1038/nature03369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glasson SS, Askew R, Sheppard B, et al. Characterization of and osteoarthritis susceptibility in ADAMTS-4-knockout mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2547–2558. doi: 10.1002/art.20558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]