Short abstract

Physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants often work in teams to deliver cancer care in ambulatory oncology practices. This is likely to become more prevalent as the demand for oncology services rises, and the number of providers increases only slightly.

Abstract

Introduction:

Physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs) frequently work as collaborative teams in oncology, and the models of practice vary. Optimizing the models for quality of care, provider and patient satisfaction, productivity, and revenue will be critical in the years to come, as stresses on the oncology workforce increase.

Methods:

Teams of physicians, NPs, and PAs at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston, MA) were studied with regard to practice models and their effects on productivity, visit fees, and provider and patient satisfaction.

Results:

Three practice models were identified, dependent on the degree to which providers saw patients together with team members or independently. Overall productivity and visit fees were similar in the three models. In addition, provider and patient satisfaction levels were high in all models.

Conclusions:

Varying models of practice among physicians, NPs, and PAs lead to relatively similar levels of productivity and fees as well as provider and patient satisfaction. It is paramount that in the years to come—as the demand for oncology services increases more rapidly than the number of providers—provider teams develop new strategies and care models with even broader participation by other members of the health care system to work more efficiently.

Introduction

Physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs) frequently work in teams to deliver care in ambulatory oncology practices.1–5 As pressures on the oncology workforce increase, with a rapidly rising demand for oncology services and only a modest increase in the number of medical oncologists, NPs, and PAs, these collaborative practices are likely to become more important and more prevalent in the delivery of cancer care in the United States.

Physicians, NPs, and PAs work together in different care delivery models. For the purpose of efficiency, we describe NPs and PAs as midlevel providers. In our cancer center (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA), each group of providers is valued for its unique skill set and knowledge base, and each serves to add to our care delivery model centered on patients and families.

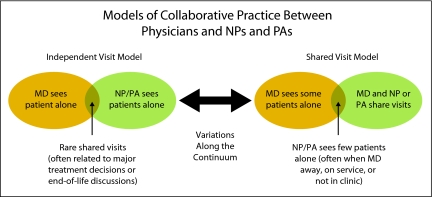

Provider team members can work relatively independently, seeing most patients individually and coming together to meet with patients at times of critical care decision points, such as initial treatment plans, tumor progression, and end-of-life decisions. We refer to this as the independent visit model (IVM). At the other extreme are teams that conduct most of their patient visits together, with the physicians and midlevel providers delivering different aspects of care individually, such as controlling symptoms, ordering chemotherapy, and obtaining consent; we refer to this as the shared visit model (SVM). A third model—the mixed visit model (MVM)—is one in which physicians and midlevel providers selectively see patients independently or together, with neither independent nor shared visits predominating.

To better understand the parameters of productivity, visit fees, and provider and patient satisfaction, we evaluated collaborative practices at our cancer center. We did not assess quality of care, patient outcomes, or relative cost of each model as part of this evaluation.

Methods

Definition of Models

Three models were identified and defined. The IVM was defined as when physicians, NPs, and PAs saw two thirds or more of their patients independently and one third or fewer together as a team. The SVM was defined as when physicians, NPs, and/or PAs saw more than two thirds of their patients together and one third or fewer independently. The MVM was defined as when physicians, NPs, and PAs saw between one third and two thirds of their patients together as a team.

Provider Satisfaction

To assess if there were any differences in provider satisfaction among the three models, three NPs and/or PAs and six physicians who primarily used the IVM were chosen to participate in this study. In addition, three NPs and/or PAs and five physicians who primarily used the SVM were chosen to participate. Therefore, a sample of 11 teams representing the extreme ends of the practice model spectrum was evaluated. All providers were privately interviewed. The interview questions included:

1) What factors have influenced your practice model?

2) How satisfied are you with your practice model?

3) Who manages non–face-to-face clinical work?

4) What do you think are the features of an ideal practice model?

Patient Satisfaction

To understand differences in patient satisfaction, 68 patients who were seen by the 11 teams during a 3-month period were randomly selected for telephone interviews. Patients were instructed to answer the questions on the basis of the Likert scale from 1 to 5. The interview questions included:

1) Are you satisfied with the care provided by your physician-NP-PA team?

2) Are you satisfied with the communication between your physician and NP and/or PA?

3) Rate your satisfaction with only seeing your NP or PA on some visits.

4) Are you satisfied with the amount of time your physician spends with you?

5) Are you satisfied with the amount of time your NP and/or PA spends with you?

Productivity and Visit Fee Analysis

A retrospective analysis of visit volume in a 1-year period for all 42 teams of physicians, NPs, and PAs at our cancer center who had worked together for at least 1 year was performed. This analysis produced average numbers of patients seen by the teams per clinic session, including new-patient visits, established-patient visits, and total visit volume. A clinical session was defined as a 4-hour period. The visit data were grouped into the three different practice models (ie, the IVM, MVM, and SVM). Physicians, NPs, and PAs at our cancer center are employed by the hospital. Therefore, a physician visit generates both professional and technical fees, whereas NP and PA visits generate a technical fee only.

Analysis of fees for each model was completed on the basis of the breakdown of average visit volume ascertained in the visit volume analysis for the three practice models (ie, the IVM, MVM, and SVM). Fee amounts (from 2005) were applied to visit volume for all three practice models.

Results

Models of Care

As shown in Figure 1, at the extremes, two models were identified. One was the IVM, in which physicians and midlevel providers largely saw two thirds or more of their patients alone. When providers did see patients together as a team, it was often to discuss issues such as initial treatment, changes in disease status or treatment, and end-of-life decisions. At the other extreme, the SVM represented practices in which two thirds or more of patients were seen by physicians and midlevel providers together. When providers saw a patient together, some of the visit was performed with just one provider, who handled specific issues such as symptom management, home care, diagnostic test scheduling and/or review, hospice care, and other treatment planning. In both models, midlevel providers often saw patients alone when physicians were out of the office, either traveling or acting as attending physician in inpatient services.

Fig 1.

Collaborative practice models.

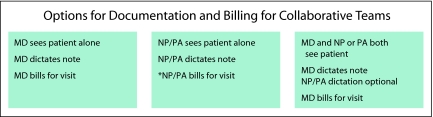

Options for documentation and billing are shown in Figure 2. Physicians who saw patients alone documented and billed for the visits. When patients were seen by midlevel providers alone, the midlevel providers documented and billed for the visits. The services for which NPs and PAs can bill vary by practice model and state. When a patient was seen by the provider team together, the physician usually documented and billed for the visit. Documentation by the NP and/or PA was optional in this situation. It was also acceptable for the NP and/or PA to document and bill for the visit even though the physician had been involved, as long as the involvement of the physician was acknowledged in the visit documentation, and the physician did not bill for the visit.

Fig 2.

Documentation and billing options. *Billing specifics for NPs/PAs may vary depending on the physician employment model and state regulations.

Productivity

Productivity was also studied in the three different practice models, including the IVM (n = 25 teams), SVM (n = nine teams), and MVM (n = eight teams). As listed in Table 1, productivity was reasonably equal in all three models, taking into account both new-patient and established-patient visits. Methodology to determine productivity involved examining clinical activity of the 25 teams in a 1-year period, not fully taking into account time away from the office for conferences, vacations, inpatient attending, and so on, and resulting in what seemed to be a low number of patient visits per session. Because the methodology was the same for all practice models, the comparative nature of the data is valid.

Table 1.

Clinical Productivity by Visit Volume Data of Three Practice Models

| Type of Visit | No. of Visits per Session | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IVM* (n = 25 teams) | MVM† (n = 8 teams) | SVM‡ (n = 9 teams) | |

| New patient | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Established patient | 6.0 | 5.9 | 6.4 |

| Total | 6.8 | 6.7 | 7.0 |

NOTE. Information presented on the basis of 1 year of fee data. Session defined as a 4-hour period.

Abbreviations: IVM, independent visit model; MVM, mixed visit model; SVM, shared visit model.

Providers see > two thirds of patients alone.

Providers see between one third and two thirds of patients together as a team.

Providers see < one third of patients alone.

Visit Fees

Table 2lists visit fees for the three practice models. Fees were relatively equal in the three models studied.

Table 2.

Visit Fees by Practice Model

| Type of Visit | IVM | MVM | SVM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Visits | Total Fees* ($) | No. of Visits | Total Fees* ($) | No. of Visits | Total Fees* ($) | |

| Physician with new patient | 208 | 162,611 | 208 | 162,611 | 156 | 121,958 |

| Physician with established patient | 1,144 | 363,758 | 1,482 | 471,232 | 1,456 | 462,964 |

| NP or PA with established patient | 416 | 86,919 | 234 | 48,892 | 182 | 38,027 |

| Total | 1,768 | 613,288 | 1,924 | 682,735 | 1794 | 622,950 |

NOTE. Billing in other circumstances may vary on the basis of physician employment status and state regulations. In some cases, NPs and PAs can only bill professional fees if both the physician and NP or PA are employed by a physician corporation separate from the institution billing the technical fee.

Abbreviations: IVM, independent visit model; MVM, mixed visit model; SVM, shared visit model; NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant.

Fees for fiscal year 2005.

Provider and Patient Satisfaction

Provider and patient satisfaction levels were assessed for the IVM and SVM but not for the MVM. As listed in Table 3, physicians and NPs were asked about factors that had led them to use a particular model, how satisfied they were with their model, who was performing nonclinical work for them, and what they thought composed an ideal practice model. All providers using the IVM reported being very satisfied. In the SVM, physicians reported being very satisfied, and midlevel providers reported being moderately satisfied.

Table 3.

Provider Satisfaction Data

| Topic | Provider Feedback | |

|---|---|---|

| IVM (n = 6 physicians, 3 NPs and/or PAs) | SVM (n = 5 physicians, 3 NPs and/or PAs) | |

| Factors influencing practice model | Clinical volume | Physician preference |

| NP/PA experience | Physician RVU targets | |

| Desire to have collaborative model built on expertise/strengths of both physicians and NPs/PAs | Easier for physician to manage schedule, given difficulty with support staff managing schedule | |

| Perception that model increases capacity and revenue | Perception that patient wants to see physician | |

| Perception that shared visits cause delays for patient | Value added by both physicians and NPs/PAs | |

| Confidence that RVUs high enough for physician to allow independent NP/PA visits | Physician desire to maintain control of patient care | |

| Skills of each clinician applied where those skills are needed | Perception that physician billing generates more revenue | |

| Physician satisfaction | Very satisfied | Very satisfied |

| NP/PA satisfaction | Very satisfied | Moderately satisfied |

| Managers of non–face-to-face clinical work | NPs/PAs, program RNs | NPs/PAs, program RNs |

| Ideal practice model features | Program RNs perform triage, manage non–face-to-face clinical work | |

| More robust clinical administrative support system for managing patient scheduling | ||

| Truly collaborative team of physicians, NPs, PAs, RNs, administrative support | ||

Abbreviations: IVM, independent visit model; SVM, shared visit model; NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant; RVU, relative value unit; RN, registered nurse.

Patient satisfaction data are listed in Table 4. Patients reported being slightly less satisfied in the IVM regarding comfort with seeing only midlevel providers on some visits. On the other hand, in the SVM, fewer patients reported satisfaction with the amount of time physicians spent with them. However, in aggregate, patient satisfaction scores were high for both models.

Table 4.

Patient Satisfaction Survey Related to Model Type

| Topic | Patient Feedback | |

|---|---|---|

| IVM (%; n = 38 patients) | SVM (%; n = 30 patients) | |

| Care received from team | ||

| Satisfied | 100 | 100 |

| Communication between physician and NP or PA | ||

| Satisfied | 95 | 97 |

| Neutral | 5 | 3 |

| Only seeing NP or PA for some visits | ||

| Satisfied | 78 | 90 |

| Neutral | 14 | 10 |

| Dissatisfied | 9 | |

| Amount of time physician spends with you | ||

| Satisfied | 97 | 86 |

| Neutral | 3 | 7 |

| Dissatisfied | 7 | |

| Amount of time NP and/or PA spends with you | ||

| Satisfied | 95 | 97 |

| Neutral | 5 | 3 |

Abbreviations: IVM, independent visit model; SVM, shared visit model; NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant.

Discussion

Collaborative practices involving physicians, NPs, and PAs are becoming increasingly critical to the delivery of oncology care and services. This is likely to become even more important as the medical oncology physician workforce becomes less able to meet the increasing demand for cancer care projected by ASCO and other organizations.6 Although there are also relative shortages of NPs and PAs, it is likely that these workforces could be increased more rapidly than the workforce of medical oncologists available to care for patients with cancer in the United States. Therefore, optimizing models of collaborative practice between physicians and midlevel providers will be critical in coming years.

As we have described, three distinct practice models have emerged among physician and midlevel provider teams at our cancer center. Several factors led to the development of these models, including beliefs among providers that their model enabled them to see a higher volume of patients and generate more revenue than they could have with another model. We have shown that the different practice models studied at our cancer center can result in relatively equal productivity and revenue generation. Although provider satisfaction was high among all physicians and midlevel providers surveyed, both the IVM and SVM teams recognized the need for a robust administrative and clinical support system so they could function as efficiently and effectively as possible.

Although patient satisfaction was relatively high in both the IVM and SVM, both providers and patients felt that patient satisfaction might be suboptimal in the SVM, depending on preconceived expectations of patients and families. The established best practice relative to this issue promulgated at our cancer center occurs on the initial visit, when a new patient and his or her family are introduced to the physician–midlevel provider team; at that time, the team explains how the physician and midlevel providers work together (both in the clinic and outside the clinic reviewing patient issues) and how future appointments will occur, with emphasis on communication and collaboration within the team. This helps set the expectations of the patient and family, and therefore, patient dissatisfaction with seeing either the physician or midlevel provider alone might be less likely.

Although we did not perform a formal analysis of the cost of each practice model, at our cancer center, annual salaries and benefit levels of midlevel providers are lower than those of physicians, and therefore, collaborative teams are potentially a less costly way to deliver high-quality care. More importantly, the unique contribution of each member of these interdisciplinary care teams adds more value to the care experience of patients and families.

The challenge in coming years will be to design models of care that are better able to significantly increase productivity while not compromising quality. We will need to closely examine the tasks that physicians, NPs, and PAs perform. Providers should be relieved of any tasks that can be performed by other personnel, freeing them to focus on delivery of care, for which they have unique training and expertise. We will need to be thoughtful when considering tasks that we ask providers to perform, weighing their usefulness in quality care, patient safety, efficiency, cost containment, and other important issues so as to not burden providers with work that does not improve outcomes in any of these areas, while retaining tasks that do improve outcomes. How registered nurses, psychosocial providers, and technical and administrative support staff contribute to the productivity and efficiency of physicians, NPs, and PAs will require additional analysis and model development to ensure that care is delivered in a way that optimizes the role of each group of providers.

Tools such as electronic health records and computerized chemotherapy order entry containing decision support and other processes to improve efficiency must be not only implemented in oncology practices but also designed in ways that facilitate and streamline care rather than impede care or add unnecessary time or effort to delivery of care.

Oncology physicians, NPs, and PAs care for patients during many aspects of care, including screening and prevention, active therapy performed in outpatient and inpatient units, cancer survivorship care, and palliative and hospice care. We must scrutinize how we structure the health care system to provide these different segments of care so that once again, we optimize the efficiency of providers caring for patients in all of these circumstances.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Lawrence N. Shulman, Lance Armstrong Foundation Survivorship Network (C), EMD Serono (C), Serenex (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

References

- 1.Hooker R, McCaig LF: Use of physician assistants and nurse practitioners in primary care, 1995–1999. Health Aff (Millwood) 20:231-238, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinney AY, Hawkins R, Hudmon KS: A descriptive study of the role of the oncology nurse practitioner. Oncol Nurs Forum 24:811-820, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulvey TM, Shuster S: Integrating nonphysician practitioners in oncology practice. Am Soc Clin Oncol Ed Book: 507-510, 2008

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Mid-Level Provider Survey Report and Supplements: October 2006

- 5.Sullivan-Marx EM: Lessons learned from advanced practice nursing payment. Policy Polit Nurs Pract 9:121-126, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, et al: Future supply and demand for oncology: Challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract 3:79-86, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]