Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To determine which staff behaviours and interventions were helpful to a family who had a child die in the intensive care unit (ICU) and which behaviours could be improved.

METHODS:

Families whose child died six to 18 months earlier were invited to participate. Families whose child’s death involved a coroner’s inquiry were excluded. Family members were interviewed by a grief counselor, and completed the Grief Experience Inventory Profile and an empirically designed questionnaire.

RESULTS:

No family refused to participate. All family members (13 families, 24 individuals) reported that they wanted, were offered and had: time to be alone with their child, time to hold the child, chances to discuss their feelings, and an opportunity to cry and express their emotions openly. Tangible mementos of the child were appreciated. Support provided by nursing staff was rated as excellent. Some physicians appeared to be abrupt, cold and unfeeling. Hospital social workers and chaplains, when available, were appreciated. Parents valued access to private space and holding their child, but these options needed to be suggested, as they did not know to ask for them. Some families wanted more information about funeral arrangements; most wanted more timely information about autopsy results and feedback on organ donations. Follow-up contact from the hospital about four weeks after the death was valued. Families saw the study as an opportunity to provide feedback that may help others.

CONCLUSIONS:

Many acute bereavement interventions need to be initiated by staff because families do not know to request them. Physicians do not always meet individual family’s needs for support. Contact initiated by staff following a death is appreciated.

Keywords: Communication, Death, Family, Follow-up, Funeral arrangements, Organ retrieval

Abstract

OBJECTIFS :

Déterminer les comportements et les interventions du personnel qui sont utiles pour une famille dont l’enfant meurt à l’unité de soins intensifs (USI) et les comportements qui pourraient être améliorés.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Des familles dont l’enfant avait péri au cours des six à 18 mois précédents étaient invitées à participer. Les familles dont le décès de l’enfant s’associait à une enquête du coroner étaient exclues. Les membres de la famille ont passé une entrevue avec un thérapeute pour les endeuillés et ont rempli le profil de l’inventaire de l’expérience du deuil ainsi qu’un questionnaire empirique.

RÉSULTATS :

Aucune famille n’a refusé de participer. Tous les membres de la famille (13 familles, soit 24 personnes) ont déclaré qu’ils avaient voulu, qu’on leur avait offert et qu’ils avaient reçu ce qui suit : du temps seul avec leur enfant, du temps pour tenir leur enfant dans leurs bras, la possibilité de discuter de leurs sentiments et l’occasion de pleurer et d’exprimer leurs émotions ouvertement. Les souvenirs tangibles de l’enfant étaient appréciés. Le soutien assuré par le personnel infirmier était évalué comme excellent. Certains médecins semblaient brusques, froids et insensibles. Le soutien des travailleurs sociaux et des aumôniers de l’hôpital, lorsqu’ils étaient disponibles, était apprécié. Les parents trouvaient important d’avoir accès à un espace privé et de tenir leur enfant dans leurs bras, mais il fallait leur suggérer ces possibilités parce qu’ils ne savaient pas pouvoir le demander. Certaines familles désiraient recevoir plus de renseignements sur les dispositions funéraires. La plupart auraient voulu recevoir de l’information plus rapidement au sujet des résultats de l’autopsie et bénéficier d’un suivi relativement au don d’organe. Un contact établi par l’hôpital environ quatre semaines après le décès était jugé précieux. Les familles ont perçu l’étude comme une occasion de fournir des commentaires qui pourraient aider d’autres familles.

CONCLUSIONS :

De nombreuses interventions immédiates pour les endeuillés doivent être suggérées par le personnel parce que les familles ne savent pas qu’elles sont autorisées à les demander. Les médecins ne respectent pas toujours les besoins de soutien des familles. Les contacts établis par le personnel après un décès sont appréciés.

The death of a child is probably the most traumatic event that a family can experience. When a child dies in an intensive care unit (ICU), interactions between the staff and the family around the time of death influence both the short term impact and the long term recovery for the family. The actions and comments of staff are remembered, often vividly and verbatim, and have the potential to alleviate or exacerbate the parents’ pain (1). Many individuals, including some ICU staff, feel very uncomfortable around parents who are losing or have just lost a child. Nursing education addresses how to cope in these situations (2,3). Physicians must learn almost exclusively from faculty role models through observation and example, because the formal medical curriculum rarely extends beyond the theoretical considerations of how to help a family deal with death (4–6). Medical staff can also perceive the death of a child as a failure on their part and experience guilt, anger or detachment (7) and, consequently, be unable to provide the parents with constructive or effective support.

The ICU at the Children’s and Women’s Health Centre of British Columbia has developed specific care strategies for use around the time of death designed to assist family members in the short and long term (Table 1). The authors’ ICU is the single tertiary care paediatric facility serving a large western Canadian province. The strategies developed are not unique to our paediatric ICU. Many premature nurseries and oncology, cardiology and perinatology programs have established support initiatives (8). However, this is an aspect of care that is rarely evaluated as a quality assurance measure, or addressed in the paediatric literature (1,9).

TABLE 1.

Bereavement care strategies specifically addressed in the questionnaire

| Ensuring that the family has time to be alone with their child |

| Suggesting that the family take opportunities to hold their child |

| Not limiting access to the child’s bedside |

| Providing access to a nurse or doctor whenever the family had questions |

| Encouraging the family to personally collect their child’s belongings |

| Offering to discuss funeral arrangements |

| Providing opportunities for individual family members to discuss their feelings |

| Validating the need for family members to cry and express their emotions openly |

| Preparing and providing mementos of the child (footprints, photos, locks of hair) |

We reviewed the available literature and conducted a study to evaluate parents’ perceptions of the impact of bereavement care. The objective of the study was to obtain feedback from parents who had a child die in our paediatric ICU and identify the components of care provided particularly well by our staff and aspects where improvements could be made. We hypothesized that there would be aspects of the care provided that more than half of families found to be positive, and aspects of care that the majority found were not well-delivered.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Behavioral Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia (#B97-0361) and the Research Review Committee of Children’s Hospital. Families who had experienced the death of a child in the authors’ paediatric ICU more than six months but less than 18 months before the study were sent a letter inviting them to participate in the study. This time period was chosen to avoid deaths that were too recent for parents to be objective, or too long ago for all relevant aspects to be remembered. Exclusion criteria were: English language comprehension below the grade 4 level (insufficient to complete the questionnaires and participate in the interview), and residence outside a 160 km (100 mile) radius of the hospital (beyond a reasonable travel distance for the interview). Families whose child’s death was ‘suspicious’ (suspected violence or abuse) or involved a coroner’s inquiry for other reasons were excluded because such cases often involve incompletely resolved legal action or complex issues on causation.

If the family returned the consent form enclosed with the letter, they were mailed copies of the Grief Experience Inventory Profile (10) and an empirically designed questionnaire, one for each caregiver, usually the father and the mother. In single-parent families, a second close family member was encouraged to participate.

The Grief Experience Inventory is a validated measure of the status grief resolution following a significant loss (10). It was developed as a means of quantifying data from individual interviews of bereaved individuals. It is made up of statements made during interviews with people experiencing grief, or by researchers describing the grief experience as they observed it. It is presented in a true or false format using simple, nonsexist language. The score is separated into 12 scales rating: denial, atypical response, social desirability, despair, anger and/or hostility, guilt, social isolation, loss of control, rumination, depersonalization, somatization and death anxiety.

The empirical questionnaire (available from the authors) addressed five areas: demographics; contact with hospital personnel; specific experiences the day the child died; support received the day the child died; and support or contact received since the child’s death. The questionnaire specifically asked about bereavement interventions that the Children’s and Women’s Health Centre of British Columbia suggests and supports (Table 1), eliciting whether they were offered, whether they were wanted and whether they happened. In addition, questions addressed the contribution of interaction with different staff members, including physicians, nurses, clinical nurse specialists, hospital chaplains, social workers, psychologists and child life workers, both on the day of the death and subsequently.

Once the questionnaires had been returned, an appointment was made for a home visit for a personal interview with a grief counsellor. To ensure objectivity, the counsellor was an experienced independent grief counsellor not based at the Children’s and Women’s Health Centre of British Columbia. The home interview followed a semi-structured format to ensure that the same issues were covered with all families. Topics covered were: the circumstances surrounding the death, positive and negative aspects of the bereavement care provided at the hospital, impact of the interventions, coping strategies they have used since the death, and any issues raised by the questionnaires. The parent(s) or family members were interviewed together.

Data analysis

The Grief Inventory was scored, and the mean and SD of the t-scores were determined for men and women separately. Results of structured questions were entered into a database and analyzed using descriptive statistics. If appropriate, the Wilcoxon signed-ranks test was used to compare scores. Open ended questions and interview responses were content coded and either reported as percentages or as specific comments.

RESULTS

No family that was invited refused to participate. Of 54 deaths, 36 families were excluded based on the exclusion criteria (approximately two thirds of patients in the authors’ ICU are from outside the Greater Vancouver area). The authors were unable to locate five of the remaining 18 families. Thirteen families were studied and 24 parents participated. The average age of the parents was 37 years (SD 6), and more than half had post-secondary education. Parents scored their religious faith on a scale of 1 to 5 (absent to extremely strong), with the mean being 3.3 (SD 1.4). The average age of the children who died was two years (median 2, range neonate to 11 years, SD 3). Four children died as a result of congenital cardiac problems, four as a result of complications of other birth defects, three following motor vehicle crashes, and two from infections (one as a corollary of neoplastic disease).

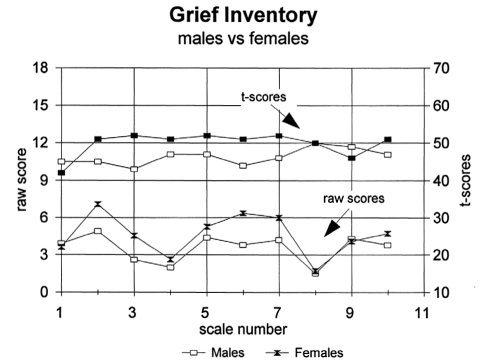

Scores on the Grief Inventory (Figure 1) indicated that, when tested (six to 18 months following the death), all parents were in the normal range on all scales, including the validity scales, with the exception of one parent’s score of 9 (the maximum score) on the anger scale, which was in the 71st percentile.

Figure 1).

The Grief Inventory raw and t-score values for male and female parents of children who died in the intensive care unit. The scales are numbered as: 1) denial; 2) atypical response; 3) social desirability; 4) despair; 5) anger; 6) social isolation; 7) loss of control; 8) somatization; 9) death anxiety; and 10) guilt

Contact with hospital personnel since the death ranged from none (three families) to frequent, ongoing contact with specific nurses (one family). Most families had received a card from their child’s primary nurse (10 of 13 or 77%). Most contact initiated by the staff involved notes or cards. Attendance at the funeral occurred in four cases. Contact initiated by the parents was usually to meet a specific goal such as seeking information on the results of autopsy or organ donation.

Of the actions or behaviors routinely suggested and supported in the authors’ ICU on the day of the child’s death, the authors specifically identified and asked parents about nine (Table 1). Six were considered to be helpful and important by at least 10 of 13 families: time to be alone with their child, time to hold their child, having as much time as they wanted at the bedside, a physician or nurse available when needed, opportunities to cry and express their feelings openly, and receiving mementos of their child. Mementos of the child such as photographs, footprints, and locks of hair were particularly appreciated. Mothers unanimously scored receiving mementos as 5 (on a scale of helpfulness of 1 to 5) whereas fathers reported this as somewhat less important (mean score 4.4). Being moved to the privacy of a single room and being able to hold their child were critically important (both scored as 5 on the scale of helpfulness), but written comments by the parents indicated that both these actions needed to be initiated by the staff as they would not have thought to ask for them.

Three interventions were desired by less than 80% of families: being able to collect the child’s belongings personally, having funeral arrangements discussed by staff, and having opportunities to discuss how they were feeling. The discussion of funeral arrangements scored the lowest. However, it was only offered to seven of 13 families, and desired by four of 11 fathers, and five of 13 mothers. The desire for opportunities to discuss feelings was different for fathers versus mothers: eight of 11 fathers (73%) versus 10 of 12 mothers (83%) (who responded to this question).

Interviews and open ended comments were unanimously positive about the contributions of nursing staff. Nurses were deemed to have provided excellent support throughout the ICU stay, on the day of the child’s death and subsequent to the death. Descriptors included great, wonderful, open, tremendous, remarkable, friendly and available. Of the nine couples that commented on the support provided by physicians, six (67%) had negative comments and three (33%) had positive comments about their interactions with the physicians. The negative comments indicated that physicians tended to appear to be rushed, distant, abrupt, cold and somewhat unfeeling; that one changed the life support withdrawal and organ retrieval schedule without discussion; and that one provided information that needed “translation and interpretation” by the nurses after the physician left. Positive comments acknowledged one physician who told the parents that they had “great courage” when they agreed to the withdrawal of life support, another who was seen as providing particularly clear information on why an autopsy was needed, and one oncologist who stopped by just to talk to the parents about how they were, and to express his condolences. Scores for nurses’ supportiveness on the day of death on a scale of 1 to 5 averaged 4.8, compared with physicians who scored 4.1 (P<0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test). Families who were provided with access to social workers and/or chaplains appreciated their involvement, and scored their support at 4.4. Those who were not offered social work or clerical support (n=4) suggested that it be available 24 h a day. Psychologists were perceived as less helpful on the day of the death, with a mean score by parents who had contact with a psychologist on that day of 4.1.

Responses to open ended questions on the questionnaire and during the interview identified several areas of ICU bereavement care that could be improved:

Four families indicated that they would have appreciated talking on the telephone to a staff member who knew them and their child two to four weeks after the death. Three families commented positively on Red Cross volunteers who maintained contact following the child’s death.

Four families indicated that they had never received autopsy results from hospital staff. The majority of parents who agreed to their child being an organ donor felt that information on the success of the donation would have been helpful to them.

Four families indicated that additional help with making funeral arrangements would have been welcome.

Three families indicated that suggesting cessation of life support treatment as an option was, or would have been, valued.

One family indicated that they wished they had held, and been encouraged to hold, their baby more than they did.

One family, for whom a social worker was called in, initially felt that there was an unspoken or implied accusation of abuse associated with this action, and therefore suggested that the role of the social worker be described more carefully before he/she is brought in.

Individual families indicated that a place to express or pump breast milk in privacy would have been appreciated; an information pamphlet or video about the hospital and ICU would have been useful; mailed information following the death would have been valued; and free parking would have been helpful.

DISCUSSION

The death of a child is a critical event, and 30% to 75% of parents can experience either clinical depression or pathological grieving following the death of their child (1). It is the responsibility of the ICU team to ensure that the care of the family through the process of dying and after death is comprehensive and meets the needs of each individual family. The role of the ICU physician involves not only providing good medical treatment, but also providing ‘a good death’ (11).

This study found that behaviors and interventions introduced in our paediatric ICU to support parents around the time of bereavement were all considered to be helpful by more than 70% of respondents. The ‘Recommendations’ section summarizes what parents found to be particularly helpful. Importantly, we found that certain acute bereavement interventions such as having parents hold their child and moving to a more private space, such as a single room, needed to be initiated by staff because families do not know to request them.

The needs of the family differ at the different stages of care. During the period of active medical treatment, even where care is family oriented, the central focus is on the care of the child. However, once death is inevitable, the focus of care must shift from provision of support to the patient to provision of support to the family (11).

At this stage, the provision of information is probably the most critical element needed by the family (12), and here physicians carry a major responsibility (13). Nurses were perceived as being very supportive, but that some physicians could improve their interactions during this phase of care. It is not the ICU physician’s responsibility to provide every piece of information, all members of the team share in this role, but some information is their personal domain, and their place in the hierarchy of care requires that they ensure that each family gets responses to all their questions and that unrequested essential details are also explained. Parents invariably seek two elements in any dialogue intended to counsel them: enough time to absorb the information, and explanation in words that they can understand (1,14). For a review of optimizing communication between physicians and parents in the paediatric ICU, see Todres et al (7). Platitudes are not welcome (15), and our own research indicates that families value caregivers who show their emotions appropriately (16), which corroborates other literature (1).

We noted differences between families as well as between members of the same family to questions about their desire for supportive interventions, and that some may be unable to ask for the support they need, or to show appreciation when it is given (17). This emphasizes the unique nature of each family member and the need for communication to be individualized.

When death has occurred, the family enters a new phase and their needs change again (12). All families need provision of information for later reference and mementos of their child, and many require the opportunity for members of their extended family or friends to see the child. Mementos tend to be valued later. A footprint or handprint, and/or a lock of the child’s hair, as well as taking care to return the child’s personal belongings in a suitable container (not a hospital plastic bag), were particularly appreciated by the families in our study.

The package of information we provide includes a description of the stages of grief; contact information for someone closely involved with the family in the hospital, who the parents can contact if they wish; and details of local bereavement support groups. We found that contact with individuals who have had a similar experience can be helpful and this is confirmed by other studies (7,17). Contact initiated by the ICU staff about one month following a child’s death was valued. As Hansen emphasizes, it is important to recognize that emotional concerns do not end when the family leaves the unit (18). Cards and notes, as described by Brown and Sefansky (3), are helpful, including ones sent for Christmas or Hanukkah, the child’s birthday, or the first anniversary of the child’s death. Todres (13) confirmed that parents appreciate some contact being maintained by a physician via a periodic telephone call. These actions support the finding that parents are unanimously concerned that their child not be forgotten (1,19).

Paediatric medical literature is largely silent on the issue of families experiencing the death of a child (1). There are few studies of the value of bereavement interventions. A review in 1990 identified four randomized studies, primarily addressing perinatal grief counselling (9,20–23). A search of MedLine from 1966 to 2002 produced no other citations. The results of studies on bereavement interventions are equivocal (9), and major elements of their design, have been questioned, including enrollment, randomization, follow-up, and outcome measures (9,19).

All eligible families in our study consented to participate but partial funding decimated our proposed recruitment. To achieve high enrolment and ongoing participation, it is critical that research in this area is funded, and that studies are conducted sensitively with interviews and questionnaires that acknowledge and address the respondent’s distress (24).

Objective outcome measures for studies of bereavement are difficult to design, because the range of normal responses to such an event is very wide, responses change with time and the differences made by the interventions are comparatively small. We selected the Grief Experience Inventory (10) as our validated outcome measure, and all our parents scored within the normal range of six to 18 months after bereavement. However, this measure may not be sufficiently sensitive when it is a child who dies. In perinatal studies the Perinatal Grief Scale is now used (25), and a similar scale is needed specific to deaths involving children.

In contrast to our parent group, Oliver and Fallat (1) found that only seven of 29 parents (24%) grieved normally when their child’s death had been sudden and due to trauma. They did use a different outcome measure, a combination of Worden’s “tasks of mourning” (26) and Demi and Miles’ parameters of normal grief (27), but it is possible that sudden death creates more problems with grieving because it deprives parents and caregivers of the time needed to establish rapport and share information fully. Our use of a grief counsellor was valuable in a research context and could help parents at risk for pathological grieving.

Our finding that negative feelings could follow communication with physicians around the time of death is not uncommon. Communication skills are a neglected area of medicine, and appropriate empathy is precariously balanced between ‘emotional detachment’, with the risk of appearing to be cold and unfeeling, and ‘over involvement’, which risks emotional exhaustion (7). However, because how we communicate ultimately determines the level of satisfaction accruing from any doctor-patient/family relationship, skills and empathy of appropriate quality must be assured. The other major parental concern voiced in our study was over delays in obtaining autopsy reports. The importance and benefits of autopsies are reviewed by Riggs and Weibley (28). Autopsies provide closure and are therefore invaluable in processing grief; they provide information and often consolation, and provision of the results provides an opening point for discussion between the physician and the family. This gives the family an opportunity to make sense of, and bring closure to, the death of their child (28). However, the timeline for autopsies needs to be explained to the parents around the time of death, and probably again in the course of follow-up phone calls, to ensure that their expectations are realistic. Then a clearly defined process needs to be in place to ensure that results are communicated once they are available.

Limitations

This observational study was conducted on a small sample size, and did not involve randomization. We studied as many families as possible with the funding granted. Our population is not optimal for several reasons.

Excluding all deaths involving families living more than 160 km away or investigation by the coroner severely limited our study population. The rationale was to avoid unreasonable travel distances (and cost) for interview, and confounders generated by major guilt, criminal proceedings and/or unresolved issues about the cause of death. In retrospect, there was probably only a need to exclude deaths where there was a suspicion of child abuse and/or criminal action, and future studies should obtain funding to enable the counsellor to travel greater distances. There may be differences between the needs of urban and rural families that were not identified in this study.

The ethnic diversity of the participants was limited because of the need for parents to speak English for the interview. Other literature (29) and an unpublished study conducted by us, indicate that individual ethnic, socioeconomic and religious groups have different needs and expectations surrounding significant illness and death.

As the roles of the different physicians providing care were not spelled out in the questionnaire, there may have been ambiguity about who was an ICU physician and who was an attending physician or surgeon, or visiting specialist or paediatrician.

It can be argued that the process we describe is more a quality assurance measure than research. Certainly, the frequency with which death occurs in most ICUs (5% to 10% of admissions) (30) means that all will offer support to such families, and many of the interventions will be similar to ours. However the quality of a unit’s supportive care is of comparable importance to other aspects of care provided, meaning that here too some measure is necessary to determine when errors of omission and commission occur for optimal care around bereavement to be assured. Our study and literature review indicate a need to define and categorize the interventions offered, and a need to implement and validate measures to evaluate their efficacy.

Although death in childhood and related family support are topics that appear occasionally in the medical literature (8,15,31–34), the small number of studies done and virtual silence on the subject of bereavement support in the mainstream paediatric literature should be regarded as unacceptable.

Recommendations

The results of this study and our review of the literature confirm our clinical impressions regarding the support families need in connection with the loss of a child. We therefore recommend the following:

Each unit has a central checklist and process in place to ensure that all relevant aspects of bereavement care are implemented before, during and following a child’s death.

The attending physician coordinates the measures necessary to meet the individual needs of the family for support.

ICU staff suggest moving the family and dying child to a single room, and that parents and family members take opportunities to hold the child.

Unit philosophy and structure support physicians being more accessible to families around the time of death.

Paediatric intensive care units have access to social workers and clergy at nights and weekends.

Timelines for organ donation/retrieval are managed to minimize conflict with parents’ needs.

Autopsy information is presented comprehensively. Telephone follow-up is made to restate the timeline and schedule discussion of the results.

Information or advice about funeral arrangements is readily available.

A designated person is always assigned to follow up with each family.

Opportunities are provided following death to promote closure for the family and staff.

Follow-up contact is made at approximately one month, and paediatric ICUs consider implementing a program similar to those of many palliative care units (use of a grief counsellor and sympathy cards sent by staff at intervals following the child’s death).

Each unit’s bereavement care is included in their quality assurance measures.

Continuing education is provided for the ICU team regarding death and dying.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oliver RC, Fallat ME. Traumatic childhood death: How well do parents cope? J Trauma. 1995;39:303–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199508000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hickey PA, Rykerson S. Caring for parents of critically ill infants and children. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 1993;4:565–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown PS, Sefansky S. Enhancing bereavement care in the pediatric ICU. Crit Care Nurs. 1995;15:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahler O, McAnarney E, Friedman S. Factors influencing pediatric interns’ relationships with dying children and their parents. Pediatrics. 1981;67:207–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macnab A. Death and dying. In: Sear M, editor. The Pocket Pediatrician. 1996. pp. 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jellinek MS, Todres ID, Catlin EA, et al. Pediatric intensive care training: Confronting the dark side. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:775–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199305000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Todres ID, Earle M, Jellinek MS. Enhancing communication: The physician and family in the pediatric intensive care unit. Ped Clin North Am. 1994;41:1395–404. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38878-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macnab AJ, Sheckter LA, Hendry NJ, Pendray MR, Macnab G. Group support or parents of high risk neonates: An interdisciplinary approach. Soc Work Health Care. 1985;10:63–71. doi: 10.1300/J010v10n04_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneiderman G, Winders P, Tallett S, Feldman W. Do child and/or parent bereavement programs work? Can J Psychiatry. 1994;39:215–8. doi: 10.1177/070674379403900404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saunders CM, Mauger PA, Strong PN. The Grief Experience Inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett MM. Death, brain death and related decision. In: Macnab AJ, MacRae D, Henning R, editors. Care of the Critically Ill Child. Toronto: Churchill Livingstone; 2001. pp. 479–83. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stedeford A. The dying patient and his family. Med North Am. 1986;37:5473–84. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Todres D. Communication between physician, patient, and family in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1993;21(Suppl 9):S383–6. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199309001-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldblum RB. Interviewing: The most sophisticated of diagnostic technologies. Ann Roy Coll Phys Surg Can. 1993;26:224–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woolley MM. The death of a child – the parent’s perspective and advice. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:73–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macnab AJ, Richards J, Green G. Family-oriented care during pediatric interhospital transport. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;36:247–57. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nyamathi A, Jacoby A, Costancia P, Ruvevich S. Coping and adjustment of spouses of critically ill patients with cardiac disease. Heart Lung. 1992;22:160–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen M, Young DA, Carden FE. Psychological evaluation and support in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Ann. 1986;15:60–9. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19860101-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliver RC, Sturtevant JP, Scheetz JP, Fallat ME. Beneficial effects of a hospital bereavement intervention program after traumatic childhood death. J Trauma. 2001;50:440–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200103000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forrest GC, Standish E, Baum JD. Support after perinatal death: A study of support and counselling after perinatal bereavement. Br Med J. 1982;285:1475–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6353.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Black D, Urbanowicz MA. Family intervention with bereaved children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1987;28:467–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1987.tb01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lake MF, Johnson TM, Murphy J, Knuppel RA. Evaluation of a perinatal grief support team. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:1203–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polak PR, Egan D, Vandenbergh R, Williams WV. Prevention in mental health. Am J Psychiatry. 1975;132:146–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.132.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kavanaugh K, Ayers L. “Not as bad as it could have been”: Assessing and mitigating harm during research interviews on sensitive topics. Res Nurs Health. 1998;21:91–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199802)21:1<91::aid-nur10>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toedter LJ, Lasker JN, Janssen HJEM. International comparison of studies using the Perinatal Grief Scale: A decade of research on pregnancy loss. Death Stud. 2001;25:205–38. doi: 10.1080/07481180125971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Worden JW. Grief Counselling and Grief Therapy: A Handbook for the Mental Health Practitioner. 2nd edition. New York: Springer Publishing Co; 1991. Attachment, loss, and the tasks of mourning; pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demi A, Miles M. Parameters of normal grief: A Delphi study. Death Stud. 1987;11:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riggs D, Weibley RE. Autopies and the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1995;41:1383–93. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38877-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waxler-Morrison N, Anderson JM, Richardson E, translators. Vancouver: University of British. Columbia Press; 1990. Cross-cultural Caring: A Handbook for Health Professionals in Western Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gemke RJB. Outcome following intensive care. In: Macnab AJ, Macrae D, Henning R, editors. Care of the Critically Ill Child. Toronto: Churchill Livingstone; 2001. pp. 498–504. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolfram RW, Timmel DJ, Doyle CR, Ackerman AD, Lebet R. Incorporation of a “Coping with the Death of a Child” module in the pediatric advanced life support (PALS) curriculum. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:242–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson B, McCall E, Leversha A, Webster L. A review of children’s dying in a pediatric intensive care unit. NZ Med J. 1994;107:345–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray JA, Terry DJ, Vance JC, Battistutta D, Connelly Y. Effects of a program of intervention on parental distress following infant death. Death Stud. 2000;24:275–305. doi: 10.1080/074811800200469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laakso H, Paunonen-Ilmonen M. Mothers’ grief following the death of a child. J Adv Nurs. 2001;36:69–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]