Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

The death of a child is a tragedy resulting in family trauma and disorganization. The present study sought to evaluate the intensity of grief experienced by parents who have lost a child in the perinatal period (stillbirth, premature baby, term baby less than one month) and parents who have lost a child after the perinatal period (one month to 18 years).

METHOD:

To compare the intensities of the bereavement reactions among grieving parents and to follow the course of such phenomena, a detailed bereavement questionnaire (the French version of the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief [TRIG-F]) was used. The TRIG-F is a three-part questionnaire that quantifies the intensity of grief near the time of death and in the present, and the perceived capacity of coping.

RESULTS:

Seventy-one bereaved parents, representing 43 families, completed the questionnaire. Parents who lost a child after the perinatal period showed grief at a higher intensity, measured by the TRIG-F, than parents who had lost a child in the perinatal period (83±22 versus 69±20 [mean±SD]; P=0.004). Mothers expressed a greater intensity of grief than fathers. No significant difference between mothers of the perinatal group and mothers of the postperinatal group was shown. Sudden death and death ocurring at home were associated with a higher grief intensity.

CONCLUSION:

Bereavement after the loss of a newborn or an older child is intense and prolonged. These findings support the importance of bereavement care for grieving parents and suggest that these parents appreciate help from health care professionals.

Keywords: Bereavement, Child, End-of-life care, Parental grief

Abstract

OBJECTIF :

Le décès d’un enfant est une tragédie qui entraîne une désorganisation et un traumatisme dans la famille. La présente étude vise à évaluer l’intensité du deuil que vivent les parents qui perdent un enfant pendant la période périnatale (bébé mort-né, bébé prématuré, bébé à terme de moins d’un mois) ou qui perdent un enfant après cette période (de un mois à 18 ans).

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Pour comparer l’intensité des réactions de deuil parmi les parents endeuillés et pour suivre l’évolution de ce phénomène, un questionnaire détaillé sur le deuil (la version française de l’inventaire révisé du deuil du Texas [TRIG-F]) a été utilisé. Le TRIG-F est un questionnaire en trois parties qui quantifie l’intensité du deuil peu de temps après le décès et dans le présent, ainsi que la perception de la capacité d’affronter la réalité.

RÉSULTATS :

Soixante et onze parents endeuillés, représentant 43 familles, ont rempli le questionnaire. L’intensité du deuil des parents qui avaient perdu un enfant après la période périnatale était plus élevée, d’après le TRIG-F, que celle des parents qui avaient perdu leur enfant pendant la période périnatale (83±22 par rapport à 69±20 [moyenne±ÉT]; P=0,004). Les mères exprimaient une intensité de deuil supérieure à celle des pères. Aucune différence significative n’était signalée entre les mères d’enfants morts pendant la période périnatale et celles d’enfants morts après cette période. Les morts subites et les décès survenus à domicile s’associaient à une intensité de deuil plus élevée.

CONCLUSION :

Le deuil après la perte d’un nouveau-né ou d’un enfant plus âgé est intense et prolongé. Ces observations appuient l’importance des soins aux parents endeuillés et indiquent que ceux-ci apprécient l’aide de professionnels de la santé.

The death of a child is a profound loss. This loss is especially difficult to endure because parents envision an entire lifetime for their child. Even before birth, parents idealize the future of their infant, and expectations and hopes can be built over time. With the death of their child, parents lose this entire future in addition to the actual emotional and physical loss (1). Studies have described the effects of such losses on parents (2–6). Reactions to the different types of loss have been described but have rarely been compared (7). Such information is important in understanding the process of bereavement and in planning appropriate support (8).

Presently, most end-of-life care for children occurs in the acute hospital setting (9). Little is known about the quality of end-of-life and bereavement care for paediatric patients in this setting (10,11). Understanding the reality of parents during and after the loss of a child is a mandatory step in improving end-of-life and bereavement care.

The aim of the present study was to identify the magnitude of grief experienced by parents following the loss of a child in the perinatal period compared with a loss after the perinatal period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample and procedures

The study included all families who lost a child in Estrie, a southeastern region of Quebec, from January 1997 to December 1999, regardless of the hospital or centre where the death occured. The perinatal group consisted of all neonatal deaths (zero to 28 days) and stillbirths (gestational age of more than 24 weeks and weight of more than 500 g). The postperinatal group consisted of other children who died during the study period (29 days to 18 years). Families whose children had died of a possible nonaccidental injury were not included. An individual contact was made to explain the study and to obtain informed consent. The questionnaire was sent to 135 parents representing 85 families. The mailing took place in July 2001. Each questionnaire packet included a cover letter explaining the survey and its voluntary and confidential nature, and a prestamped return envelope. Individual members of each couple were asked to answer their own questionnaire separately.

The French translation of the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief (TRIG-F) is a standardized multidimensional measure of grief consisting of three subscales. TRIG1 consists of eight items that address feelings and actions at the time of death (early grief). TRIG2 consists of eleven items that focus on present feelings (long term grief). TRIG3 consists of seven items (four with five-point scale answers and three with true or false answers) that measure the perceived aptitude of coping (12,13). This structure allows for the measurement of the evolution of grief reactions over time. Each subscale consists of various statements that the respondents rate on a five-point scale from “completely true” to “completely false”. TRIG1 scores range from eight to 40, TRIG2 scores from 11 to 55 and TRIG3 from eight to 26. Higher scores indicate a higher intensity of grief. The TRIG-F has been shown to be a reliable and valid instrument for the assessment of grief for adult subjects (12). The TRIG-F contains questions about the nature of the disease and the expectedness of the child’s death.

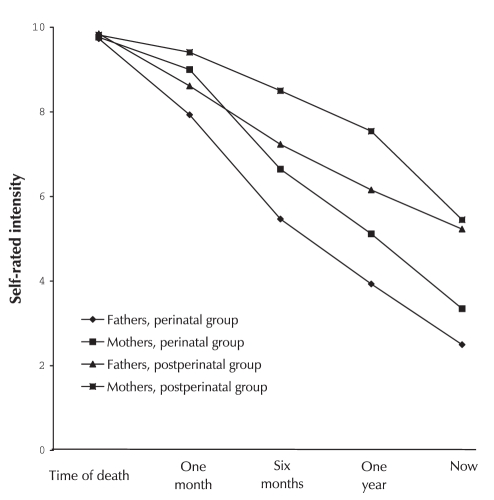

The parents were also asked to rate on a scale from one to 10 (10 being the strongest intensity) their grief immediately following the death of their child, after one month, six months, a year and at the time they completed the questionnaire. Divorce, substance abuse, psychiatric diagnosis and problems at work were investigated. Parents who were diagnosed and treated pharmacologically for major depression and/or an anxiety disorder were considered to have a psychiatric diagnosis.

The chi square test was used for ordinal variables. The TRIG-F measures were used to study parents’ characteristics associated with the perceived intensity of grief. The Mann-Whitney U rank test was used to examine relationships between the TRIG-F and other dimensions of parents’ responses. Spearman’s rank correlation test was used to identify linear relationships between TRIG-F scores and other continuous variables. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

One hundred eighty-five parents were eligible for the study. Of the 137 parents contacted, 135 agreed to receive the questionnaire and 71 returned them completed (32 parents from the perinatal group and 39 from the postperinatal group). The deceased children ranged in age from zero (six stillborn infants) to 17 years of age (Table 1). In 28 cases, both parents completed the questionnaire. Therefore, questionnaires representing 43 different families comprised the data set. Parents ranged in age from 22 to 67 years, with a median age of 38 years (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of dead children

| Perinatal group (n=17) | Postperinatal group (n=26) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in months (median [range]) | 0 (0–0.75) | 120 (3–215) |

| Gestational age (weeks) (median [range]) | 37.5 (24–41) | – |

| Sex (F:M) | 10:7 | 17:9 |

| Unexpected death | 12 (71%) | 18 (69%) |

| Time since death (mean ± SD) | 36±9 months | 37±11 months |

F Female; M Male

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of bereaved parents

| Perinatal group (n=32) | Postperinatal group (n=39) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 33±5 years | 43±8 years |

| Sex (F:M) | 17:15 | 25:14 |

| Catholics | 97% | 85% |

| Income less than CAD$20,000/year | 9% | 28% |

| Parents with at least a high school diploma | 88% | 69% |

| Marital status before the child’s death (% married) | 53% | 61% |

| Surviving children (median) | 2 | 2 |

F Female; M Male

Mothers perceived more intensity of grief than fathers and parents in the postperinatal group experienced more intensity of grief than parents in the perinatal group (Tables 3–5). No significant difference between mothers of the perinatal group and mothers of the postperinatal group was found.

TABLE 3.

Results of the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief (French translation) (TRIG-F)

| TRIG-F (total)* | Early grief (TRIG1) | Long term grief (TRIG2) | Perceived aptitude of coping (TRIG3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 76 (21) | 21 (8) | 39 (10) | 16 (6) |

| Perinatal group | 69 (20)a | 19 (7)c | 35 (11)d | 15 (5)g |

| Mothers | 75 (16)b | 20 (6) | 39 (8)e | 15 (4) |

| Fathers | 62 (23)b | 17 (9) | 31 (12)e,f | 14 (6) |

| Postperinatal group | 83 (22)a | 22 (8)c | 43 (8)d | 18 (6)g |

| Mothers | 85 (18) | 23 (8) | 44 (6) | 18 (6) |

| Fathers | 79 (23) | 21 (8) | 40 (10)f | 18 (7) |

Values are mean (SD);

P=0.007 TRIG-F between both groups;

P=0.03 mothers versus fathers in the perinatal group;

P=0.04 TRIG1 between both groups;

P=0.004 TRIG2 between both groups;

P=0.02 TRIG2 between mothers and fathers in the perinatal group;

P=0.04 fathers in the perinatal group versus fathers in the postneonatal group;

P=0.02 TRIG3 between both groups

TABLE 5.

Intensity of grief after the loss of a child after the perinatal period

| Early grief (TRIG1)* | Long term grief (TRIG2) | Perceived aptitude of coping (TRIG3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | 23±8 | 44±6 | 18±6 |

| Fathers | 21±8 | 41±10 | 18±7 |

| Expectedness of death | |||

| Unexpected | 23±8 | 45±8† | 19±6 |

| Expected | 20±10 | 38±5† | 15±4 |

| Place of death | |||

| Hospital | 20±8‡ | 42±7 | 17±6 |

| Home | 27±6‡ | 44±6 | 20±5 |

Values are mean (SD);

P=0.007 TRIG2 between expected versus unexpected death;

P=0.02 TRIG1 between death at home versus death in the hospital setting

Parents whose child died unexpectedly had higher long term grief scores (TRIG2) than parents who could anticipate the death. In the postperinatal group, there were no differences found between mothers and fathers. Parents whose child died at home had higher early grief scores (TRIG1) than parents whose child died in the hospital setting. In the perinatal group, mothers had a higher intensity of long term grief than fathers.

No correlation between TRIG-F scores and age of the child in the postperinatal group or between TRIG-F scores and gestational age in the perinatal group was observed. No correlation between time since death and TRIG-F scores was shown. Figure 1 shows the self-rated intensity of grief as perceived by parents.

Figure 1).

Self-rated intensity of grief as perceived by parents on a scale from one to 10 (10 being the strongest intensity)

Twenty-five parents (36%) were spontaneously offered follow-up bereavement care (Table 6). Of those, 83% thought the meeting was helpful. Those who had been helped by their physician commented on how helpful this support had been. Only 10% had made contact with a local support group.

TABLE 6.

Health care providers involved in bereavement care

| Health care providers involved in bereavement care* | Total | Perinatal group | Postperinatal group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physician | 17 | 5 | 12 |

| Psychologist | 11 | 3 | 8 |

| Social worker | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Nurse | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Priest | 3 | 2 | 1 |

More than one professional could be involved with one parent

Differences in individual answers to the questionnaire were noted. Responses to issues that were different between parent groups and that are relevant to counselling are shown in Table 7.

TABLE 7.

Issues relevant to different grief reactions in parents after the loss of a child

| Questions* | Perinatal group | Perinatal group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Mother | Father | Total | Mother | Father | |

| Early grief | ||||||

| I increased work after the death | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| I found it hard to work | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| I lost interest in family, friends | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| Felt the need to do things I would have done with my child | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| Long term grief | ||||||

| I hide my tears when I think about him/her | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| Nobody will take his/her place in my life | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Things and people around me still make me think about him/her | + | + | + | + | ++ | + |

| I still feel the need to cry for him/her | − | + | − | ++ | ++ | + |

| I am perturbed every year at the date of his/her death | + | + | − | ++ | ++ | + |

| I am perturbed at Christmas | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| I can’t accept his/her death | − | − | − | − | − | + |

Only questions with different answers between the groups (P<0.05, Mann-Whitney U);

++ Greater than four on the likert scale;

+ Greater than three on the likert scale;

− Less than three on the likert scale

Eighteen parents (26%) were diagnosed with major depression by a physician after the death of their child. Three parents had a diagnosis of anxiety disorder. The rate of psychiatric diagnosis was different between the two groups (four of 32 in the perinatal group compared with 17 of 39 in the postperinatal group, P=0.003). Parents with major depression diagnosed by a physician had higher intensities in all three TRIG-F scores (P<0.05). Ten parents (14%) reported substance abuse problems. Fathers and parents with low annual incomes were more likely to report such problems (P=0.002 and P=0.001, respectively).

Of the 42 families involved in the study, 15 had other children with 67 children in total (the number by family ranged from zero to four with a median of two). There was no significant relationship between the number of surviving children in the family and the intensity of grief as measured by the TRIG-F.

DISCUSSION

The present study supports many ideas put forward in other descriptive studies about the reactions of parents after the loss of a child (1–5). The intensity of grief is much higher than the grief experienced by a population of young adults having lost a first-degree relative (12,13). Our findings indicate that parents who lost a child after the perinatal period were affected differently than parents who lost a child in the perinatal period. Grief intensity measured by the TRIG-F, by the self-evaluation of intensity of grief and the rate of psychological distress are higher for parents in the postperinatal group than in the perinatal group. Differences between the responses of mothers and fathers are noted consistently in both groups. No difference was found between the mothers of the two groups. Fathers in the perinatal group seemed to be affected differently mainly in long term grief. These differences should not necessarily be interpreted as fathers showing less grief than mothers. For example, more fathers experienced alcohol problems following the death of their child. This might illustrate a more inward projection of feelings or an attempt to negate these feelings, whereas mothers may externalize their reactions more.

Parents whose child died at home had higher early grief than parents whose child died in a hospital setting. Families who took their child home to die commented on how difficult it was to obtain qualified palliative care, especially during the last days before death. This problem of access to qualified palliative care deserves close attention.

A significant proportion of parents in our study experienced psychological distress leading to a psychiatric diagnosis by their physician. The role of the physician may be particularly important for monitoring parents’ long term grief resolution, and for determining any degree of pathological grieving, including marital stress and substance abuse. Finding out how the grieving process is progressing and giving parents insight into its natural progression should be a part of this follow-up. The authors believe that a formal structure for bereavement follow-up is needed. While bereavement is a natural process, associations with morbidity have been shown (14,15). Risk assessment and intervention strategies need to be developed in conjunction with community and primary care services and should strive to complement both these services and the natural networks of the bereaved, rather than supplanting either one.

Limitations of the present study include the retrospective nature of the questionnaire. To complete the first part of the TRIG-F, parents were asked to think back about their feelings and behaviours near the time of death. However, it seems unlikely that parents would forget the circumstances surrounding their child’s death. Also, because the study was retrospective, it was impossible to control for other life stresses that could affect parents. The sample size was relatively small and consisted predominantly of caucasian, French-speaking parents, which limits generalisation of the results. Highly educated parents and parents who have specific complaints they wish to be known may have been more inclined to participate. Because the questionnaire was administered anonymously, there was no information on the characteristics of the nonrespondents.

The information outlined here highlights the emotional intensity associated with the period surrounding the death of a child. Differences between mothers and fathers are noted in both groups of grieving parents. This grieving process is associated with a great level of psychological distress. Physicians are in a unique position to help parents at this time of loss. We hope the experiences described in the present paper will help health care providers to further understand and support bereaved parents.

TABLE 4.

Intensity of grief after the loss of a child in the perinatal period

| Early grief (TRIG1)* | Long term grief (TRIG2) | Perceived aptitude of coping (TRIG3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | 20±6 | 39±8† | 15±4 |

| Fathers | 17±9 | 31±12† | 14±6 |

| Expectedness of death | |||

| Unexpected | 18±9 | 34±12 | 15±5 |

| Expected | 19±7 | 36±11 | 15±5 |

| Place of death | |||

| Hospital | 18±7 | 34±11 | 15±5 |

| Home | 21±7 | 39±9 | 15±5 |

Values represent mean (SD);

P=0.03 mothers versus fathers

REFERENCES

- 1.Ryan R. Loss in the neonatal period: Recommendations for the pediatric health care team. In: Woods JR, Esposito Woods JL, editors. Loss During Pregnancy or in the Newborn Period: Principles of Care with Clinical Cases and Analyses. Pitman: Jannetti Publications Inc; 1997. pp. 125–57. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennell JH, Slyter H, Klaus MH. The mourning response of parents to the death of a newborn infant. N Engl J Med. 1970;283:344–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197008132830706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vance JC, Foster WJ, Najman JM, Embelton G, Thearle MJ, Hodgen FM. Early parental responses to sudden infant death, stillbirth or neonatal death. Med J Aust. 1991;155:292–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1991.tb142283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Frain JD, Ernst L. The psychological effects of sudden infant death syndrome on surviving members. J Fam Pract. 1978;6:985–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vance JC, Najman JM, Thearle MJ, Embelton G, Foster WJ, Boyle FM. Psychological changes in parents eight months after the loss of an infant from stillbirth, neonatal death, or sudden infant death syndrome – a longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 1995;96:933–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkley-Best E, Kellner K. The forgotten grief: A review of the psychology of stillbirth. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1982;52:420–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyregrov A, Matthiesen SB. Stillbirth, neonatal death and sudden infant death (SIDS): Parental reactions. Scand J Psychol. 1987;28:81–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.1987.tb00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray JA, Terry DJ, Vance JC, Battistutta D, Connolly Y. Effects of a program of intervention on parental distress following infant death. Death Stud. 2000;24:275–305. doi: 10.1080/074811800200469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crain N, Dalton H, Slonim A. End-of-life care for children: Bridging the gaps. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:695–6. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200103000-00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frager G. Pediatric palliative care: Building the model, bridging the gaps. J Palliat Care. 1996;12:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sahler OJ, Frager G, Levetown M, Cohn FG, Lipson MA. Medical education about end-of-life care in the pediatric setting: Principles, challenges, and opportunities. Pediatrics. 2000;105:575–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paulhan I, Bourgeois M. The TRIG (Texas Revised Inventory of Grief) questionnaire. French translation and validation. Encephale. 1995;21:257–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paulhan I, Bourgeois M. Grief experience by 154 young adults in the general population (value of the TRIG grief scale). Texas Revised Inventory of Grief. Encephale. 1995;21:263–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turton P, Hughes P, Evans CD, Fainman D. Incidence, correlates and predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder in the pregnancy after stillbirth. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:556–60. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.6.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore IM, Gilliss CL, Martinson I. Psychosomatic symptoms in parents 2 years after the death of a child with cancer. Nurs Res. 1988;37:104–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]