Abstract

Although the perturbation of either the dopaminergic system or brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels has been linked to important neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders, there is no known signaling pathway linking these two major players. We found that the exclusive stimulation of the dopamine D1–D2 receptor heteromer, which we identified in striatal neurons and adult rat brain by using confocal FRET, led to the activation of a signaling cascade that links dopamine signaling to BDNF production and neuronal growth through a cascade of four steps: (i) mobilization of intracellular calcium through Gq, phospholipase C, and inositol trisphosphate, (ii) rapid activation of cytosolic and nuclear calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase IIα, (iii) increased BDNF expression, and (iv) accelerated morphological maturation and differentiation of striatal neurons, marked by increased microtubule-associated protein 2 production. These effects, although robust in striatal neurons from D5−/− mice, were absent in neurons from D1−/− mice. We also demonstrated that this signaling cascade was activated in adult rat brain, although with regional specificity, being largely limited to the nucleus accumbens. This dopaminergic pathway regulating neuronal growth and maturation through BDNF may have considerable significance in disorders such as drug addiction, schizophrenia, and depression.

Keywords: brain-derived neurotrophic factor activation, calcium signaling pathway, calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II, neuronal maturation, GPCR oligomerization

Dopamine promotes neuronal differentiation, maintenance, and survival (1–4) by modulating the transcription of different genes. Little however, is known regarding the molecular events that govern these dopamine-mediated effects. Evidence has emerged indicating a positive relationship between functions mediated by dopamine and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and its receptor TrkB (2–7). However, a direct mechanism bridging dopamine signaling to BDNF has not yet been described. Classically, dopamine exerts its actions through D1-like (D1, D5) and D2-like (D2, D3, D4) receptors, which regulate activation or inhibition of cAMP accumulation, through Gs/olf or Gi/o proteins, respectively (8). Other signaling cascades have also been reported (9, 10), including phosphatidylinositol turnover in brain through D1-like receptor activation (11, 12), but no such activation was observed when the cloned D1 receptor was expressed (13–15). These observations led us to the discovery of the dopamine D1–D2 receptor heterooligomer, which is able to mobilize intracellular calcium (15–18). However, the signaling cascade and the physiological functions of the dopamine D1–D2 receptor heteromer in brain are unknown.

Because calcium is involved in the activation of BDNF signaling (19), we hypothesized that this pathway may be central to dopamine activation of BDNF and subsequent neuronal maturation and differentiation.

In this context, we describe a signaling pathway that links dopamine action through the D1–D2 receptor heterooligomer to the expression of BDNF in postnatal striatal neurons and in adult rat brain by a mechanism involving activation of Gq, phospholipase C (PLC), the mobilization of intracellular calcium, activation of cytoplasmic and nuclear calcium/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent kinase IIα (CaMKIIα) and subsequently an increase in BDNF expression. Furthermore, we also highlight the physiological consequences resulting from the activation of this signaling pathway on neuronal maturation and growth during development and its existence in nucleus accumbens of adult rat brain. Finally, using confocal FRET, we demonstrate the presence of the D1–D2 receptor heterooligomer as a physical entity in striatal neurons and rat brain.

Results

Dopamine D1 and D2 Receptors Form Heterooligomers in Striatal Neurons.

Immunocytochemistry revealed the majority of postnatal striatal neurons in culture for 7–21 days expressed D1 and D2 receptors mainly at the cell surface and on neurites with a high degree of colocalization in >90% of the neurons (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1a). Confocal FRET analysis showed that D1 and D2 receptors were in close proximity with a relative distance of 5–7 nm (50–70 Å) localized in microdomains, where FRET efficiency (E) ranged from 0.1 to 0.5, higher in the soma and proximal dendrites and lower in distal processes (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1b). Coimmunoprecipitation of D1–D2 receptor complexes from the striatum is shown (Fig. S1c). Data showed D2 receptor as a broad band of 55- to 70-kDa protein and an oligomeric form >170 kDa, whereas D1 receptor existed as bands at ≈55, ≈70, and ≈75–80 kDa, probably caused by different degrees of glycosylation. The data clearly indicate that D1 and D2 receptors can be coimmunoprecipitated from the striatum.

Fig. 1.

Colocalization, FRET analysis, and calcium mobilization of dopamine D1–D2 receptor heteromer in striatal neurons. (A) Immunocytochemistry showing endogenously expressed dopamine D1 and D2 receptor colocalization (merged) and interaction (FRET). (B) D1–D2 receptor heteromer activation leads to rapid (Insets) and dose-dependent mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ by dopamine or SKF 83959. (C) D1 antagonist SCH (10 μM) or D2 antagonist raclopride (10 μM) abolished intracellular Ca2+ mobilization triggered by D1-D2 receptor heteromer activation by 100 nM dopamine or 100 nM SKF 83959. (D) 2-APB (100 μM), inhibitor of IP3 receptors, abolished the intracellular Ca2+ increase elicited by 100 nM SKF 83959. (E) SQ 22536 (SQ, 10 μM), an adenylyl cyclase inhibitor, had no effect on intracellular Ca2+ mobilization triggered by 100 nM dopamine. (F) Pertussis toxin (PTX) (50 nM), inhibitor of Gi/o proteins had no effect on dopamine-induced Ca2+ mobilization. *, significant difference from basal (P < 0.01). Data represent mean ±SEM of values from at least three different experiments.

Coexpression, together with the coimmunoprecipitation, and the proximity of the receptors within same neurons indicated a physical interaction and heteromer complex formation between the natively expressed dopamine D1 and D2 receptors.

Intracellular Calcium Mobilization Through the Dopamine D1–D2 Receptor Heteromer.

The calcium signaling pathway was evaluated by using cameleon (20). In the absence of extracellular calcium, agonist treatments showed rapid increases in cameleon FRET, reflecting an immediate rise in intracellular calcium (Fig. 1B Insets). Both dopamine and SKF 83959, a D1-D2 heteromer agonist (17, 18), dose-dependently mobilized intracellular calcium (Fig. 1B), with a higher maximal peak effect for dopamine (Emax 0.5 versus 0.35 for SKF 83959), but equivalent EC50 values (170 nM for dopamine and 152 nM for SKF 83959). SCH 23390, a D1-specific antagonist, and raclopride, a D2-specific antagonist, blocked the effects of both dopamine and SKF 83959 (Fig. 1C), suggesting that dopamine- or SKF 83859-induced calcium mobilization was mediated by the D1–D2 receptor heterooligomer.

Quinpirole, a D2 agonist, at concentrations <10 μM, showed no effect (Fig. S2a) but at higher concentrations (≥10 μM) triggered calcium mobilization (Fig. S2a). These quinpirole concentrations are far higher than its affinity constant (Kd 1.5–2.2 nM) for D2 receptor in rat striatal membranes (21) and would not be specific for D2 receptors. However, 1–100 nM quinpirole used concomitantly with equivalent concentrations of SKF 83959 showed an effect one to two times greater than the effect of SKF 83959 alone (Fig. S2b), indicating a synergistic effect of D1 and D2 receptor activation. SKF 83822, which exclusively activates the cAMP pathway (17, 18), showed no significant effect on intracellular calcium release (Fig. S2c), suggesting the noninvolvement of this pathway. To ensure specificity of D1–D2 receptor heteromer involvement, the calcium mobilization, performed with striatal neurons from dopamine D5 receptor null (D5−/−) mice showed robust SKF 83959-triggered intracellular calcium rise (Fig. S2d), with an amplitude equivalent to that observed in neurons from WT animals (FRET 0.27 ± 0.04 versus 0.31 ± 0.03, respectively), which was abolished by SCH 22390 and raclopride (Fig. S2d), suggesting the involvement of D1 and D2 receptors. No calcium mobilization, however, was observed in neurons from D1−/− mice. Thus, intracellular calcium mobilization by dopamine or SKF 83959 in striatal neurons involved the D1–D2 receptor heterooligomer and a synergistic cooperation between the receptors within the heteromer, without involvement of the dopamine D5 receptor.

Characteristics of the D1–D2 Receptor Heteromer-Mediated Calcium Release.

Calcium mobilization studies performed in the absence of extracellular calcium excluded calcium entry via calcium channels. The exclusive involvement of intracellular calcium was confirmed by preincubation with 10 μM thapsigargine (TPG), which attenuated calcium release caused by SKF 83959 by 80% and that caused by dopamine by ≈75% (Fig. S2e). The source of intracellular calcium was assessed with 100 μM 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB), which inhibits inositol trisphosphate (IP3) receptor-dependent calcium stores and abolished calcium mobilization elicited by SKF 83959 (Fig. 1D).

Lack of involvement of the Gs–AC pathway in calcium mobilization by the D1–D2 receptor heteromer was shown by SQ22536 (SQ; 10 μM), an inhibitor of AC, which had no effect on dopamine-dependent mobilization of intracellular calcium (Fig. 1E). Pertussis toxin (PTX), an inhibitor of Gi/o proteins, had no effect on the calcium release induced by SKF 83959 or dopamine (Fig. 1F), suggesting noninvolvement of Gi/o proteins in this process. Gq involvement was assessed by preincubation with YM 254890 (YM; 100 nM), a Gq-specific inhibitor (22). No significant effect on basal calcium levels was noted, but SKF 83959- and dopamine-triggered calcium mobilization was inhibited by 90% (Fig. 2A), implicating a role for Gq/11. Immunocytochemistry of Gq/11 (Fig. 2B) revealed it localized largely in the cytosol under basal conditions. When neurons were treated with 100 nM SKF 83959 or dopamine for 2–5 min, Gq was more concentrated at the cell surface and less present in the cytosol. Quantification of Gq fluorescence (Fig. S3) revealed agonists increased Gq at the cell surface by 28 ± 2.7% after 2 min and ≈65 ± 4% after 5 min (Fig. S3) of treatment, whereas cytosolic labeling decreased by 21% and 50%, respectively (Fig. S3). Together, these results indicated the involvement of Gq, and the exclusion of Gs and Gi/o proteins, in calcium mobilization through the D1–D2 receptor heteromer.

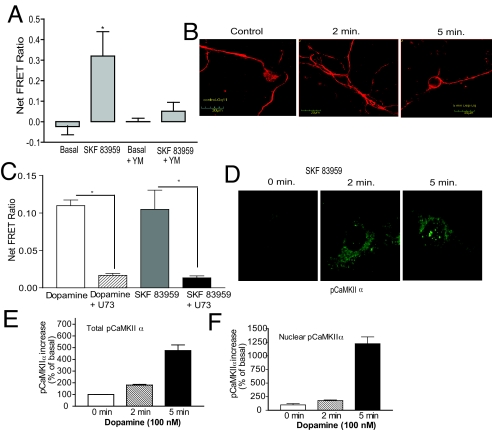

Fig. 2.

Involvement of Gq, intracellular calcium, and CaMKIIα in the D1-D2 heteromer signaling pathway in striatal neurons. (A) Inhibition of 100 nM SKF 83959-triggered intracellular Ca2+ mobilization by Gq-specific inhibitor YM 254890 (YM, 100 nM). (B) Time-dependent trafficking of endogenous Gq, after treatment with vehicle (control, 0 min) or SKF 83959 (100 nM) for 2 and 5 min. (C) Intracellular Ca2+ mobilized by SKF 83959 with or without U73122, inhibitor of PLC. (D) Increase in phosphoCaMKIIα (pCaMKIIα) following treatment with vehicle or 100 nM SKF 83959 for 2 min or 5 min in cytosol and nucleus. (E) Quantification of total pCaMKIIα fluorescence (cytosolic + nuclear) over the basal. (F) Quantification of pCaMKIIα fluorescence in the nuclear compartment over the basal level. Data represent mean +SEM of values from at least three different experiments. *, significant difference from control (P < 0.01).

The involvement of Gq and sensitivity of the calcium stores to IP3 suggested a role for PLC. Treatment with U73122, a PLC inhibitor, attenuated calcium elevations seen with SKF 83959 and dopamine (Fig. 2C), indicating that PLC was involved in the calcium mobilization triggered by activation of the D1–D2 receptor heteromer. Thus identified is a signaling pathway in striatal neurons, whereby activation of the dopamine D1–D2 receptor heteromer led to the subsequent rapid activation and translocation of Gq, activation of PLC and mobilization of intracellular calcium from stores sensitive to IP3.

Induction of CaMKIIα Activation and Nuclear Translocation.

Because intracellular calcium changes affect CaM, we investigated whether CaMKIIα was modulated through the D1–D2 receptor heteromer-dependent calcium signal. In the absence of extracellular calcium, striatal neurons were treated with vehicle, SKF 83959, or dopamine for 2 or 5 min (Fig. 2D). In the basal state, a weak signal for phosphoCaMKIIα (pCaMKIIα) was observed mainly in the cytosol. Upon treatment, total pCaMKIIα fluorescence increased ≈2- and 4-fold after 2 and 5 min, respectively (Fig. 2E). Not only was there an increase in cellular pCaMKIIα levels, but there was a robust increase of pCaMKIIα in the nucleus (Fig. 2D). At basal state, no pCaMKIIα was observed in the nucleus, suggesting that it either translocated from the cytosol to the nucleus or preexisting nuclear CaMKIIα was activated. Quantification of nuclear pCaMKIIα levels showed that the effect was rapid, occurring within 2 min of treatment, and further dramatically increased after 5 min of treatment, when nuclear pCaMKIIα levels rose over basal by >12-fold (Fig. 2F). The SKF 83959-induced activation of CAMKIIα was blocked by raclopride (Fig. S4b), indicating the involvement of both dopamine D1 and D2 receptors. CaMKIIα was similarly activated in striatal neurons from D5−/− mice (Fig. S4a) treated (5 min) with dopamine or SKF 83959. Here again, the increase in pCaMKIIα in cytosol was accompanied by an increase in the nucleus (Fig. S4). No CaMKIIα activation by dopamine or SKF 83959 was observed in neurons from D1−/− mice. Taken together, these results indicated that calcium signaling, elicited by specific activation of the dopamine D1–D2 receptor heteromer, activated CaMKIIα in the cytosol and in the nuclei of striatal neurons with no involvement of the D5 receptor.

Activation of BDNF in Striatal Neurons.

Because BDNF gene expression is modulated by nuclear isoforms of CaMKII (23), we assessed whether BDNF was activated by the D1–D2 heteromer signaling pathway. In the absence of extracellular calcium in the basal state, BDNF immunolabeling showed a weak expression level, mainly localized to cytosol, with little or no BDNF expression in neurites and axons (Fig. 3A, control). Treatment with dopamine or SKF 83959 showed a time-dependent increase in BDNF levels, evident after 1 h and significantly higher after 2 h at three and seven times higher than basal levels (Fig. 3 A and B). It was noted that a significant perinuclear, likely ER localization of BDNF was apparent after agonist treatment during all observation periods, suggesting novel synthesis of BDNF (Fig. 3A, white arrows). Agonist-induced BDNF expression was also observed in neurites and axons (Fig. 3A, yellow arrows). A Western blot indicating agonist-induced production of BDNF is shown in Fig. 3C. This effect was inhibited by the D1 and D2 antagonists (Fig. 3C and Fig. S4b), indicating the involvement of the D1–D2 receptor heteromer. BDNF expression was also enhanced in striatal neurons from D5−/− mice after treatment with SKF 83959 (Fig. S4c), whereas no alteration in BDNF expression was observed in striatal neurons from D1−/− mice (Fig. S4d), suggesting the exclusive involvement of D1 but not D5 receptors.

Fig. 3.

Striatal enhanced BDNF expression and neuronal maturation through D1-D2 receptor heteromer activation. (A) Increased BDNF expression after treatment with vehicle (control), SKF 83959 (100 nM) for 2 hours, or dopamine (100 nM) for 2 or 72 hours, in the absence of extracellular calcium. Note perinuclear BDNF (white arrows), and axonal/dendritic BDNF (yellow arrows). Nuclei were labeled with DAPI. Magnified images are shown in the Bottom frames. (B) Quantification of BDNF immunofluorescence after treatment with dopamine for 5 min, 1 hr, and 2 hrs. (C) Western blot analysis showing an agonist-induced BDNF expression and the inhibition of this effect by the antagonists, raclopride (10 μM) and SCH (10 μM). (D) Confocal images of striatal neurons treated, in the absence of extracellular calcium, with vehicle (Left, control), SKF 83959 (Upper Right, 100 nM) or dopamine (Lower Right, 100 nM), from postnatal day 4 through day 10 (PN 4–10). Note the difference in arborization and connections between control and agonist-treated neurons. (E) Confocal microscopy of immunolabeled MAP2 following treatment (PN 4–10), in the absence of extracellular calcium, with vehicle (Left, control), SKF 83959 (Upper Right, 10 nM), or dopamine (Lower Right, 500 nM). Nuclei were labeled with DAPI. Note the dense and extensive MAP2 labeling in agonist-treated neurons.

Consequences of Activating the D1–D2 Signaling Pathway: Neuronal Growth and Differentiation.

Because the D1–D2 signaling cascade reached the nucleus through CaMKIIα and activated local synthesis of BDNF, we surmised a link may exist between the activation of the calcium signaling pathway and neuronal developmental and/or survival signaling by BDNF. Striatal neurons were treated with 10–100 nM SKF 83959 or dopamine from postnatal days 4–10 and compared with vehicle treatment. Treatments were performed overnight (12–14 h) in the absence of calcium, followed by removal of treatment media and replacement by fresh culture media. A significant proportion of neurons treated by the dopaminergic agonists differentiated earlier (Fig. 3D and Fig. S5), with a phenotype equivalent to that of neurons in culture for at least 15 days (Fig. 3D), when they usually reach maturation (3, 4). After agonist treatment, the neurons were no longer isolated as usually seen up to day 10, but instead had enhanced growth of neurites, forming connections with others at a distance, indicative of a more differentiated and mature stage (Fig. 3D and Fig. S5). We confirmed these observations by microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) labeling (Fig. 3E and Fig. S5a), which is the major protein that regulates the structure and stability of microtubules, neuronal morphogenesis, cytoskeleton dynamics, and organelle trafficking in axons and dendrites (1). In newborn rat brain, MAP2a appears between postnatal days 10 and 20, during the dendritic growth phase when neurons have reached their mature morphology (1). In untreated cells, MAP2 labeling was restricted to the cell body and certain small processes, probably axons (Fig. 3E and Fig. S5a). In contrast, striatal neurons treated by SKF 83959 or dopamine showed dense MAP2 expression, within long processes extending between neurons making contact. This finding indicated that more MAP2, probably MAP2a, was produced because of dopamine agonist treatments and led to accelerated neuronal maturation and growth. The SKF 83959 effect was inhibited in the presence of raclopride, indicating the involvement of both D1 and D2 receptors (Fig. S5b). Moreover, this effect, while present in neurons derived from D5−/− mice (Fig. S5c), was absent in neurons derived from D1−/− mice (Fig. S5d), underscoring the necessary involvement of the D1 receptor. These data, as a whole, suggested that activation of the D1–D2 receptor heteromer signaling pathway was a key cascade transducing dopaminergic signals involved in the development, maturation, and differentiation of striatal neurons, through activation of BDNF signaling.

Evidence of Activation of the D1–D2 Receptor Heteromer Signaling Pathway in Adult Rodent Brain.

Colocalization of D1 and D2 receptors in some neurons within the striatum (24–27), although representing an important finding, does not indicate whether such receptors form heteromers. Immunohistochemistry in rat striatum showed that certain neurons coexpressed D1 and D2 receptors, whereas others expressed only one of the receptors. In caudate putamen, few neurons coexpressed D1 and D2 receptors. Within the nucleus accumbens, there were more neurons coexpressing D1 and D2 receptors, mainly at the cell surface (Fig. 4 and Fig. S6). Confocal FRET analysis using fluorophore-labeled antibodies measured the interaction between the colocalized receptors, as illustrated for nucleus accumbens shell (Fig. 4) and core (Fig. S6). FRET analysis showed that in most neurons where D1 and D2 receptors were colocalized the receptors were physically close enough to generate a FRET signal, whereas, noncolocalized receptors were unable to generate any FRET (Fig. 4B and Fig. S6). The distance between the receptors showed D1 and D2 were in close proximity with an average distance of 4–7 nm (40–70 Å), and high FRET efficiency was detected in nucleus accumbens. These data clearly indicated in adult rat nucleus accumbens the presence of neurons coexpressing D1 and D2 receptors, which existed close enough to permit energy transfer and therefore may be considered to be physically interacting, forming receptor heteromers.

Fig. 4.

D1-D2 receptor heteromer localization and enhancement of BDNF expression in rat nucleus accumbens. (A) Confocal FRET analysis of D1 and D2 receptor interaction in rat nucleus accumbens shell region. Anti-D2-Alexa 350 and anti-D1-Alexa 488 were used as donor and acceptor dipoles. Analysis shows processed FRET (pFRET) and distances separating the two receptors. FRET signal was detected only in neurons coexpressing D1 and D2 receptors. (B) Microdomains [regions of interest (ROIs)] within neurons coexpressing D1 and D2 receptors (Bi, Upper) or expressing D2 exclusively (Bii, Lower) were analyzed. Average FRET efficiency (E) and distance between donor and acceptor are shown. A distance ≥10 nm indicates no FRET. (C) BDNF expression in rat nucleus accumbens core and shell regions from animals treated with vehicle (saline), SKF 83959, or SKF 83822. (D) Quantification of BDNF-positive neurons (Left) and densitometry within each neuron (Right) from animals treated with vehicle (saline), SKF 83959, or SKF 83822 were assessed. Results represent mean +SEM of values from 4–5 rats/group.

We then assessed whether BDNF expression in the adult rat striatum could be stimulated through activation of the D1–D2 heteromer. Rats were treated once daily for a total of three injections with saline (control), 0.4 mg/kg of SKF 83959, or 0.4 mg/kg of SKF 83822. Changes in BDNF expression were evident in nucleus accumbens (Fig. 4C) and not in caudate nucleus, which was in keeping with the distribution of the D1–D2 heteromers observed. Compared with saline-treated rats, SKF 83959-treated animals showed a 49 ± 9% increase in the number of BDNF-positive cells in nucleus accumbens core, whereas no increase was observed in SKF 83822-treated rats (Fig. 4D). Quantification of expression in individual neurons by densitometry showed that, compared with saline-treated animals, the level of BDNF increased in cells from animals treated with SKF 83959 (Fig. 4D Upper Right), whereas no increase was observed in SKF 83822-treated animals, confirming that the activation of the calcium pathway, and not the cAMP pathway, increased both the number of cells expressing BDNF and the concentration of BDNF within cells in the nucleus accumbens core. The number of BDNF-positive neurons of control rats was higher in the nucleus accumbens shell region than core region (Fig. 4D Left). This number was not significantly different from saline-treated rats in the shell region of SKF 83959- or SKF 83822-treated rats (Fig. 4D Lower Left), although a small increase was observed in SKF 83959-treated animals. However, when BDNF expression was quantified by densitometry in individual shell neurons the level of BDNF in cells from animals treated with SKF 83959 increased by a significant 26.8% compared with cells from saline-treated animals (Fig. 4D Lower Right), whereas no increase was observed in cells from animals treated with SKF 83822.

This finding suggests that the activation of the calcium pathway, and not the cAMP pathway, increased the production of BDNF within the nucleus accumbens core and shell neurons of adult rat brain after D1–D2 receptor heteromer activation.

Discussion

We describe a dopaminergic signaling pathway occurring in neonatal striatal neurons and adult rat brain, involving activation of the dopamine D1–D2 receptor heterooligomer-, Gq-, PLC-, and IP3 receptor-mediated intracellular calcium mobilization, resulting in CaMKIIα activation in both cytosolic and nuclear compartments, leading to enhanced BDNF production. This process resulted in enhanced neuronal maturation, differentiation, and growth. We also showed through confocal FRET the occurrence of heteromers of endogenously expressed native dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in striatal neurons in culture and in adult rat brain in situ.

We showed that ≈90% of the cultured striatal neurons coexpress both D1 and D2 receptors. However, this number was lower in adult rat brain than in the cultured neurons and varied among the regions, with a high of ≈25% in the nucleus accumbens, and a lower degree of colocalization in the caudate putamen (CPu) (≈6%). Our results are consistent with the reported levels of D1 and D2 colocalization in cultured neurons and adult rat striatum. In fact, the D1 and D2 colocalization in the striatum has been a matter of long debate. It is believed that D1 and D2 receptors are localized in two anatomically segregated sets of neurons, forming the striatonigral D1-enriched direct pathway and the striatopallidal D2-enriched indirect pathway (28–30). Data from BAC transgenic mice, using EGFP driven by D1 or D2 receptor promoters, were consistent with this view (30–35). BAC data analysis also showed that at least 10–17% of medium spiny neurons (MSNs) coexpress both D1 and D2 receptors (30, 34, 35), with higher prevalence in ventral striatum (up to 17%) than in dorsal striatum (≈1–6%) (34, 35). Evidence for neuronal colocalization of D1 and D2 receptors has also been indicated by electrophysiological studies (36), immunohistochemistry (24, 25), electron microscopy (37), and retrograde labeling (26). In dissociated, cultured striatal neurons from fetal (38), neonatal (39), and 2- to 3-week-old (40) rats D1 and D2 were colocalized in a significantly higher number of neurons (60–100%) than in the adult striatum (15, 24, 27, 38, 39). The discrepancy between the results observed in adult striatum versus those observed in cultured striatal neurons may be caused in part by the lack in the cultures of afferents and glial cells. Another explanation may be a regulation of each receptor type during development, leading to different levels of receptor colocalization within brain regions.

Our study indicates that these colocalized receptors were in close physical proximity allowing the formation of receptor heterooligomers, both in striatal neurons in culture and in brain tissue. Furthermore, no known functional relevance has been attached to the neurons where D1 and D2 receptors colocalized, and our findings indicate that the receptor heteromers have a unique signaling pathway linking dopamine and BDNF through a rapid rise in calcium signaling and CaMKII activation. This finding may indicate a more significant role for the dopamine-activated calcium signaling cascade during striatal development, whereas it is relegated to have a more specialized and circumscribed role in the adult striatum, largely confined to nucleus accumbens. These findings also suggest that in addition to the two separate direct and indirect pathways, another set of neurons form a third pathway, where both receptors interact to generate another specialized signal. This may help to explain, at least in part, the cooperativity between D1 and D2 receptors observed by many (40, 41).

Dopamine-induced control of gene expression, which is important in long-term synaptic plasticity (42, 43), has been shown to occur in striatum and other brain regions (43), but the molecular mechanisms of the information transfer from the cytoplasm to the nuclei of striatal neurons are still poorly understood (44). Our results showing activation of CaMKIIα both in the cytoplasm and nucleus, as an immediate consequence of the D1–D2 heteromer stimulation and calcium release, represents an expedient mechanism by which this information could lead to rapid gene regulation. Whether activated CaMKIIα was directly translocated to the nucleus or an intermediary component, such as the recently reported dopamine-controlled inhibition of nuclear protein phosphatase-1 (44), is responsible for the activation of preexisting nuclear CaMKIIα remains to be determined.

After the increase in CaMKIIα activity, we observed an increase in BDNF expression. We also observed, in rat brain, a significant increase in the production of BDNF by neurons from the nucleus accumbens, suggesting a regional specificity for the activation of this pathway in adult brain. It is notable that these results suggested that BDNF could be synthesized locally by striatal neurons. Thus, there exists a direct link between dopaminergic signaling and BDNF expression through activation of the D1–D2 receptor heteromer. Repeated activation of the D1–D2 heteromer pathway led to accelerated growth of the neurites and connections between striatal neurons, indicating enhanced maturation and differentiation of striatal neurons, with notably increased MAP2 expression. These results are consistent with the ability of dopamine and BDNF to promote neuronal maturation, differentiation, and survival and to stimulate lengthening and arborization of neuronal processes (1–4). Our results, modeled in Fig. 5, suggest that the effects of dopamine in this particular case are mediated through the D1–D2 receptor heteromer-, Gq-, PLC-, IP3-dependent signaling pathway, using calcium as a second messenger, which is responsible for CaMKIIα activation, notably in the nucleus, where it stimulates BDNF synthesis, which in turn activates protein synthesis responsible for neuronal maturation and differentiation. In adult brain, this signaling pathway is region-specific and highly circumscribed, likely confined to the neurons expressing the D1–D2 receptor heteromer.

Fig. 5.

Model of dopamine D1–D2 receptor heteromer signaling pathway. Activation of the D1–D2 receptor heteromer leads to intracellular calcium mobilization from IP3 receptor-sensitive stores through a cascade of events involving rapid translocation of Gq to plasma membrane and activation of PLC. Calcium mobilization triggers the activation of CaMKIIα in the cytosol and the nuclear compartment, either by a translocation of activated CaMKIIα (pCaMKIIα) or the activation of a nuclear isoform of CaMKIIα. In the nucleus, pCaMKIIα triggers gene expression and protein synthesis, especially an enhanced BDNF expression. Through its trophic effects, BDNF would trigger the growth, maturation, and differentiation of striatal neurons.

Because of the major roles played by both dopamine and BDNF in many aspects of neuronal maturation and survival, any disequilibrium in the presently described D1–D2 heteromer pathway linking dopamine to BDNF may have dramatic consequences that undermine neuronal morphology, adaptation, and survival, potentially leading to neuropsychiatric disorders. Alterations in BDNF levels caused by complications in the prenatal development period, early childhood events, or adult stress were associated with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia (45), depression (46), or drug addiction (47). A neurotrophin hypothesis linking dysfunction of BDNF to the emergence of symptoms of schizophrenia has been postulated (48), and there are reports of associations between dysfunction of calcium signaling and its related proteins, including Gq, IP3, and CaMKII, with schizophrenia (49). A link between D1 and D2 receptors was shown to be missing in postmortem striata from patients with schizophrenia and Huntington disease (50).

The importance of the different receptor signaling complexes in mediating specific dopamine functions is being revealed. Ultimately, alterations of one dopamine receptor in early developmental stages, or even in the adult, may induce differences in the balance of the heteromeric/homomeric complexes and be at the origin of complicated diseases, such as schizophrenia, depression, or drug addiction.

In summary, we have demonstrated a signaling pathway triggered by the activation of the dopamine D1–D2 receptor heteromer that bridges the action of dopamine to BDNF expression, with an important physiological function of neuronal maturation and growth. A dopamine signaling pathway using calcium as a second messenger, targeting the nucleus through CaMKII activation and leading to enhanced BDNF production, may potentially be of considerable importance in the postnatal development of striatal neurons and in nucleus accumbens function in the adult. The signaling cascade described here may indicate the presence of a third pathway consisting of neurons containing D1 and D2 receptor heteromers, in addition to the already well-characterized direct and indirect pathways. Finally, our findings also represent an opportunity for drug discovery strategies to target particular signaling pathways within the dopaminergic system.

Materials and Methods

Confocal Microscopy FRET and Data Processing.

Paraformaldehyde-fixed striatal neurons or floating sections (10 μm) from rat brain were incubated for 24 h at 4 °C with primary antibodies highly specific to D1 and D2 receptors (15) and the specie-specific secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 350 dyes, respectively. Anti-D2-Alexa Fluor 350 was used as a donor dipole, while anti-D1-Alexa Fluor 488 was used as acceptor dipole. The images were acquired with an Olympus Fluoview FV 1000 laser scanning confocal microscope with a 60×/1.4 NA objective. The donor was excited with a krypton laser at 405 nm, while the acceptor was excited with an argon laser at 488 nm. The emissions were collected with 430/20- and 530-nm LP filter. Other FRET pairs (488–568 and 568–647) were tested and showed comparable results. Eleven images were acquired for each FRET analysis in accordance with an algorithm (51) (Tables S1 and Table S2). The processed FRET (pFRET) images were then generated based on the described algorithm (51), in which: pFRET = UFRET − ASBT − DSBT, where UFRET is uncorrected FRET and ASBT and DSBT are the acceptor and the donor spectral bleed-through signals, respectively. The rate of energy transfer efficiency (E) and the distance (r) between the donor (D) and the acceptor (A) molecules were estimated by selecting small regions of interest (ROI) using the same images and software, based on the following equations: E = 1 − IDA/[IDA+ pFRET × ((ψdd/ψaa) × (Qd/Qa))], where IDA is the donor image in the presence of acceptor, ψdd and ψaa are collection efficiencies in the donor and acceptor channels, respectively, and Qd and Qa are the quantum yields. E is proportional to the sixth power of the distance (r) separating the FRET pair. r = R0 [(1/E) − 1]1/6. Ro is the Förster's distance.

Calcium Measurements Using Cameleon YC6.1.

Calcium mobilization was measured by using cameleon YC6.1 (generous gift from M. Ikura, University of Toronto), an engineered calcium indicator based on the dependence of CaM conformation on elevations of calcium concentration (20). An increase in calcium binding to CaM leads to a decrease in the distance separating the two flanking proteins, CFP and YFP, and results in a measurable FRET change (20). Using a single excitation wavelength at 405 nm, which solely excites CFP, images and fluorescence emissions data for both CFP and YFP were collected. The experiments were performed in live neurons in the absence of extracellular calcium, and the data obtained from each individual cell were used to calculate the ratios, reflective of the energy transferred. The background signal was subtracted from the values obtained after drug injection.

Additional materials, methods, and related references are available in SI Text.

Acknowledgments.

The work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Drug Abuse. S.R.G. is the holder of a Canada Research Chair in Molecular Neuroscience.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0903676106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Schmidt U, et al. Activation of dopaminergic D1 receptors promotes morphogenesis of developing striatal neurons. Neuroscience. 1996;74:453–460. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwakura Y, Nawa H, Sora I, Chao MV. Dopamine D1 receptor-induced signaling through TrkB receptors in striatal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15799–15806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801553200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivkovic S, Ehrlich ME. Expression of the striatal DARPP-32/ARPP-21 phenotype in GABAergic neurons requires neurotrophins in vivo and in vitro. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5409–5419. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05409.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ivkovic S, Polonskaia O, Fariñas I, Ehrlich ME. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates maturation of the DARPP-32 phenotype in striatal medium spiny neurons: Studies in vivo and in vitro. Neuroscience. 1997;79:509–516. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00684-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berton O, et al. Essential role of BDNF in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in social defeat stress. Science. 2006;311:864–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1120972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guillin O, Abi-Dargham A, Laruelle M. Neurobiology of dopamine in schizophrenia. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;78:1–39. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)78001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monteggia LM, et al. Essential role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in adult hippocampal function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10827–10832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402141101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Missale C, Nash SR, Robinson SW, Jaber M, Caron MG. Dopamine receptors: From structure to function. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:189–225. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SK, et al. Par-4 links dopamine signaling and depression. Cell. 2005;122:275–287. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaulieu JM, et al. An Akt/β-arrestin 2/PP2A signaling complex mediates dopaminergic neurotransmission and behavior. Cell. 2005;122:261–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Undie AS, Friedman E. Stimulation of a dopamine D1 receptor enhances inositol phosphates formation in rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;253:987–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang TS, Bezprozvanny I. Dopamine receptor-mediated Ca2+ signaling in striatal medium spiny neurons. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:42082–42094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dearry A, et al. Molecular cloning and expression of the gene for a human D1 dopamine receptor. Nature. 1990;347:72–76. doi: 10.1038/347072a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedersen UB, et al. Characteristics of stably expressed human dopamine D1a and D1b receptors: Atypical behavior of the dopamine D1b receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;267:85–93. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(94)90228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SP, et al. Dopamine D1 and D2 receptor coactivation generates a novel phospholipase C-mediated calcium signal. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35671–35678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.So CH, et al. D1 and D2 dopamine receptors form heterooligomers and cointernalize after selective activation of either receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:568–578. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.012229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rashid AJ, et al. D1–D2 dopamine receptor heterooligomers with unique pharmacology are coupled to rapid activation of Gq/11 in the striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:654–659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604049104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rashid AJ, O'Dowd BF, Verma V, George SR. Neuronal Gq/11-coupled dopamine receptors: An uncharted role for dopamine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng A, Wang S, Yang D, Xiao R, Mattson MP. Calmodulin mediates brain-derived neurotrophic factor cell survival signaling upstream of Akt kinase in embryonic neocortical neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7591–7599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207232200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Truong K, et al. FRET-based in vivo Ca2+ imaging by a new calmodulin-GFP fusion molecule. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:1069–1073. doi: 10.1038/nsb728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lepiku M, Rinken A, Järv J, Fuxe K. Modulation of [3H]quinpirole binding to dopaminergic receptors by adenosine A2A receptors. Neurosci Lett. 1997;239:61–64. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00874-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takasaki J, et al. A novel Gαq/11-selective inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47438–47445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeuchi Y, Yamamoto H, Miyakawa T, Miyamoto E. Increase of brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene expression in NG108–15 cells by the nuclear isoforms of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Neurochem. 2000;74:1913–1922. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shetreat ME, Lin L, Wong AC, Rayport S. Visualization of D1 dopamine receptors on living nucleus accumbens neurons and their colocalization with D2 receptors. J Neurochem. 1996;66:1475–1482. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66041475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levey AI, et al. Localization of D1 and D2 dopamine receptors in brain with subtype-specific antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8861–8865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng YP, Lei WL, Reiner A. Differential perikaryal localization in rats of D1 and D2 dopamine receptors on striatal projection neuron types identified by retrograde labeling. J Chem Neuroanat. 2006;32:101–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong AC, Shetreat ME, Clarke JO, Rayport S. D1- and D2-like dopamine receptors are colocalized on the presynaptic varicosities of striatal and nucleus accumbens neurons in vitro. Neuroscience. 1999;89:221–233. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00284-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerfen CR. The basal ganglia. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. New York: Academic; 2004. pp. 455–508. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Moine C, Bloch B. D1 and D2 dopamine receptor gene expression in rat striatum: Sensitive cRNA probes demonstrate prominent segregation of D1 and D2 mRNAs in distinct neuronal populations of the dorsal and ventral striatum. J Comp Neurol. 1995;355:418–426. doi: 10.1002/cne.903550308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee KW, et al. Cocaine-induced dendritic spine formation in D1 and D2 dopamine receptor-containing medium spiny neurons in nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:3399–3404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511244103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gong S, et al. A gene expression atlas of the central nervous system based on bacterial artificial chromosomes. Nature. 2003;425:917–925. doi: 10.1038/nature02033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lobo MK, Karsten SL, Gray M, Geschwind DH, Yang XW. FACS-array profiling of striatal projection neuron subtypes in juvenile and adult mouse brains. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:443–452. doi: 10.1038/nn1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shuen JA, Chen M, Gloss B, Calakos N. Drd1a-tdTomato BAC transgenic mice forsimultaneous visualization of medium spiny neurons in the direct and indirect pathways of the basal ganglia. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2681–2685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5492-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bertran-Gonzalez J, et al. Opposing patterns of signaling activation in dopamine D1 and D2 receptor-expressing striatal neurons in response to cocaine and haloperidol. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5671–5685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1039-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matamales M, et al. Striatal medium-sized spiny neurons: Identification by nuclear staining and study of neuronal subpopulations in BAC transgenic mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calabresi P, Mercuri N, Stanzione P, Stefani A, Bernardi G. Intracellular studies on the dopamine induced firing inhibition of neostriatal neurons in vitro: Evidence for D1 receptor involvement. Neuroscience. 1987;20:757–771. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hersch SM, et al. Electron microscopic analysis of D1 and D2 dopamine receptor proteins in the dorsal striatum and their synaptic relationships with motor corticostriatal afferents. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5222–5237. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05222.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aizman O, et al. Anatomical and physiological evidence for D1 and D2 dopamine receptor colocalization in neostriatal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:226–230. doi: 10.1038/72929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iwatsubo K, et al. Dopamine induces apoptosis in young, but not in neonatal, neurons via Ca2+-dependent signal. Am J Physiol. 2007;293:C1498–C1508. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00088.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Capper-Loup C, Canales JJ, Kadaba N, Graybiel AM. Concurrent activation of dopamine D1 and D2 receptors is required to evoke neural and behavioral phenotypes of cocaine sensitization. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6218–6227. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-06218.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harsing LG, Jr., Zigmond MJ. Influence of dopamine on GABA release in striatum: Evidence for D1–D2 interactions and nonsynaptic influences. Neuroscience. 1997;77:419–429. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nestler EJ. Molecular basis of neural plasticity underlying addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:119–128. doi: 10.1038/35053570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thoenen H. Neurotrophins and neuronal plasticity. Science. 1995;270:593–598. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stipanovich A, et al. A phosphatase cascade by which rewarding stimuli control nucleosomal response. Nature. 2008;453:879–884. doi: 10.1038/nature06994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Angelucci F, Brene S, Mathe AA. BDNF in schizophrenia, depression, and corresponding animal models. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:345–352. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kozisek ME, Middlemas D, Bylund DB. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptor tropomyosin-related kinase B in the mechanism of action of antidepressant therapies. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;117:30–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graham DL, et al. Dynamic BDNF activity in nucleus accumbens with cocaine use increases self-administration and relapse. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1029–1037. doi: 10.1038/nn1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.HashimotoT, et al. Relationship of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptor TrkB to altered inhibitory prefrontal circuitry in schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2005;25:372–383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4035-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lidow MS. Calcium signaling dysfunction in schizophrenia: A unifying approach. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;43:70–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(03)00203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seeman P, Niznik HB, Guan HC, Booth G, Ulpian C. Link between D1 and D2 dopamine receptors is reduced in schizophrenia and Huntington diseased brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:10156–10160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.10156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen Y, Elangovan M, Periasamy A. FRET data analysis: The algorithm. In: Periasamy A, Day RN, editors. Molecular Imaging: FRET Microscopy and Spectroscopy. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 2005. pp. 126–145. [Google Scholar]