It has long been appreciated that plants, algae, phototrophic and chemoautotrophic bacteria, and archaea are able to grow by using carbon dioxide (or bicarbonate) as their sole source of carbon. This feat enables such organisms to function as the ultimate synthetic machines as they are able to synthesize all of the needed building blocks of life via the bioconversion of the most oxidized form of carbon found in the biosphere to the reduced organic carbon compounds required for cell metabolism. Studies over the years, primarily with various microbes, have indicated that some organisms may accomplish this autotrophic existence by means distinct from the usual and well-studied paradigms. In this issue of PNAS (1), the finishing touches for the completion of a previously proposed novel route of carbon assimilation are presented for the model organism Chloroflexus aurantiacus. This pathway enables synthesis of necessary metabolic intermediates from CO2/HCO3− and involves unique enzymatic steps (1).

There is an interesting history relative to the discovery of metabolic schemes by which organisms may reduce and then grow at the expense of oxidized inorganic carbon. Elegant studies, performed some 50–60 years ago, first elucidated the metabolic pathway by which CO2 could be reduced to the level of organic carbon in plants, algae, and bacteria (2, 3). This scheme, the Calvin–Bassham–Benson (CBB) pathway, for many years was thought to be the only route by which CO2 could serve as sole carbon source. Then, in the mid-1960s, Arnon and colleagues (4) showed that there was another way, the reductive tricarboxylic acid (RTCA) cycle, which enabled certain anaerobic phototrophic bacteria to accomplish an autotrophic existence without using the CBB pathway. Indeed, the RTCA pathway was shown to be less energetically expensive than the CBB route (4). Later, a third CO2 reduction pathway, the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway, was described and shown to be used by acetogenic bacteria and many archaea (5). The discovery of filamentous bacteria that inhabit and give an orange tinge to various hot springs (6) then led to the finding that one such organism, C. aurantiacus, secretes a novel metabolite, 3-hydoxypropionate, as a potential intermediate of CO2 and acetate metabolism (7). Studies over the years basically confirmed that this organism, and certain relatives, use a distinct and fourth CO2 fixation pathway (8), but until the study by Zarzycki et al. (1) was performed, many key details were not apparent, especially how the organism might assimilate key intermediates formed by previously known steps. It should also be noted that two additional CO2 fixation pathways are now known to occur in various archaea, with a total of six known autotrophic CO2 fixation pathways now documented (9, 10).

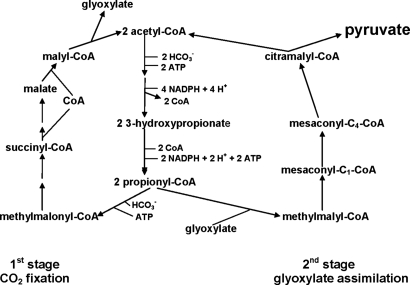

Previous studies had indicated that the first part of the hydroxypropionate pathway involved the bicarbonate-dependent formation of malyl-CoA, involving several steps, including the use of two carboxylating enzymes, acetyl-CoA and propionyl-CoA carboxylase (11). Malyl-CoA is then cleaved into two carbon units, resulting in the formation of glyoxylate and the regeneration of acetyl-CoA. This last step basically completes the first part of the hydroxypropionate pathway. Although it had been presumed that glyoxylate might then be further assimilated (12), presumably to pyruvate, the means by which this occurred was not readily apparent. The major finding of the present study is the elucidation of the enzymatic steps by which glyoxylate and propionyl-CoA may be further assimilated to pyruvate, with acetyl-CoA as an additional product. The regeneration of acetyl-CoA connects the second half of the pathway to the first, to allow a complete and enclosed cyclic pathway for net assimilation of all potential intermediates, with pyruvate serving as the key precursor compound for all other biosynthetic processes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Abridged outline of the completed 3-hydroxypropionate pathway of CO2 assimilation in C. aurantiacus showing two distinct stages. In the first part of this scheme, CO2 fixation leads to the formation of glyoxylate and acetyl-CoA. The second part of the pathway involves the assimilation of glyoxylate, with propionyl-CoA, to eventually form a dicarboxylic CoA ester, which is then cleaved to generate pyruvate and acetyl CoA. The acetyl-CoA formed in the second stage allows closure of the cycle with the first stage, while the pyruvate produced is used as a precursor metabolite for all subsequent metabolism.

Zarzycki et al. (1) demonstrated that the second part of the hydroxypropionate pathway involves the condensation of two-carbon and three-carbon intermediates (glyoxylate and propionyl-CoA, respectively). This process results in the formation of methylmalyl-CoA, which is then converted to mesaconyl-C1-CoA. The next step is particularly noteworthy as the CoA moiety is subsequently shifted within the molecule from the C1-carboxyl group to the C4-carboxyl to form mesaconyl-C4-CoA. This then leads to the formation of the C5-dicarboxylic acid CoA ester citramalyl-CoA, which subsequently is cleaved to form pyruvate and acetyl-CoA, thus completing and cyclizing the pathway. All of the requisite enzymes that catalyze the newly identified steps of the second stage that serve to complete the overall pathway have been identified, purified, and partially characterized. Clearly, these proteins present the opportunity for some very interesting and challenging mechanistic enzymology, especially the CoA transferase that catalyzes the intramolecular CoA transfer between the two carboxyl groups (Fig. 1). Moreover, in many cases, multifunctional enzymes are involved that catalyze more than one step of this pathway, thus providing some economy in the level of protein synthesis required to actuate this pathway.

In addition to interesting fundamental issues relative to the structure and function of newly described enzymes, the complete elucidation of this fourth CO2 fixation scheme or hydoxypropionate pathway raises many other interesting questions. Not the least of which is the reason this metabolic route seems, at least at this time, to be distributed in such a limited suite of organisms. Is there thus any real selective advantage of this pathway for the organisms that use it? Moreover, the reported levels of activity for key enzymatic steps are reported to be only ≈2.5- to 3.5-fold higher from extracts of autotrophically grown C. aurantiacus compared with extracts from heterotrophically grown cells (1). Are these levels of activity reflective of different amounts of synthesized enzymes? There is also some suggestion that the genes that encode the enzymes of this pathway might be regulated, yet the above enzyme activity levels may not be congruent with this idea. Certainly it is not clear at this time what might be the purpose for regulating these genes, especially because the data thus far available indicate that the enzymes and the genes of this pathway are “on” all of the time. Indeed, what purpose is there to basically having a functional hydroxypropionate pathway under photoherotrophic growth conditions? One is reminded that despite highly regulated CO2 fixation gene expression under autotrophic growth conditions, organisms that use the CBB pathway have a real need for this pathway when growing photoheterotrophically, because excess reducing equivalents from the oxidation of organic carbon are preferentially shunted to CO2 via the low basal levels of CBB enzymes. Thus, in this instance CO2 serves as a necessary electron acceptor to balance the redox potential of the cell (13). Does the hydroxypropionate pathway play a similar role in C. aurantiacus under photoheterotrophic growth conditions or are the high levels of activity seen under heterotrophic conditions suggestive of another function? Because many of the enzymes of this pathway resemble other proteins, it is not beyond the realm of possibility that the hydroxypropionate pathway enzymes are used for other purposes in the cell. Many of these questions, and other interesting issues that arise relative to photosynthesis in these organisms (14) could be answered by developing a genetic system for C. aurantiacus. Perhaps the studies reported here will stimulate such studies.

Glyoxylate and propionyl-CoA may be further assimilated to pyruvate, with acetyl-CoA as an additional product.

Acknowledgments.

Work on CO2 fixation regulation and biochemistry in my laboratory is supported by Department of Energy Grant DE-FG02–08ER15976 from the Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences Division of the Office of Basic Energy Biosciences.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 21317.

References

- 1.Zarzycki J, Brecht V, Muller M, Fuchs G. Identifying the missing steps of the autotrophic 3-hydroxypropionate CO2 fixation cycle in Chloroflexus aurantiacus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21317–21322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908356106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassham JA, Calvin M. The Path of Carbon in Photosynthesis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice–Hall; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quayle JR. The metabolism of one-carbon compounds by microorganisms. Adv Microbial Physiol. 1972;7:119–203. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans MC, Buchanan BB, Arnon DI. A new ferredoxin-dependent carbon reduction cycle in a photosynthetic bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1966;55:928–934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.55.4.928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ljungdahl L, Wood HG. Total synthesis of acetate from CO2. I. Comethylcobric acid and CO-(methyl)-5-methoxybenzimidizolylcobamide as intermediates with Clostridium thermoaceticum. Biochemistry. 1965;4:2771–2780. doi: 10.1021/bi00888a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierson BK, Castenholz RW. A phototrophic gliding filamentous bacterium of hot springs, Chloroflexus aurantiacus, gen and sp nov. Arch Microbiol. 1974;100:5–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00446302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holo H, Grace D. Chloroflexus aurantiacus secretes 3-hydroxypropionate, a possible intermediate in the assimilation of CO2 and acetate. Arch Microbiol. 1989;151:252–256. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alber BE, Fuchs G. Propionyl-coenzyme A synthase from Chloroflexus aurantiacus, a key enzyme of the hydroxypropionate cycle for autotrophic CO2 fixation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12137–12143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg IA, Kockelkorn D, Buckel W, Fuchs G. A 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate autotrophic carbon dioxide assimilation pathway in archaea. Science. 2007;318:1782–1786. doi: 10.1126/science.1149976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huber H, et al. A dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate autotrophic carbon assimilation cycle in the hyperthermophilic Archaeum Ignococcus hospitalis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7851–7856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801043105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herter S, Fuchs G, Bacher A, Eisenreich W. A bicyclic autotrophic CO2 fixation pathway in Chloroflexus aurantiacus. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20277–20283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herter S, et al. Autotrophic CO2 fixation by Chloroflexus aurantiacus, study of glyoxylate formation and assimilation via the 3-hydroxypropionate cycle. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4305–4316. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.14.4305-4316.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romagnoli S, Tabita FR. Carbon dioxide metabolism and its regulation in nonsulfur purple photosynthetic bacteria. In: Hunter CN, Daldal F, Thurnauer MC, Beatty JT, editors. The Purple Phototrophic Bacteria. Vol 28. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2009. pp. 563–576. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bryant DA, Frigaard N-U. Prokaryotic photosynthesis and phototrophy illuminated. Trends Microbiol. 2006;14:488–496. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]