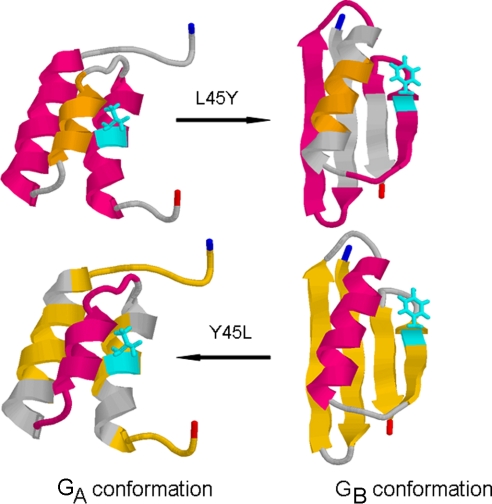

In this issue of PNAS, Alexander et al. (1) report an observation that will be a topic of heated discussion among biochemists for a long time to come. A single amino acid substitution can, in the right context, completely change the fold of a protein. And the structural change produced by this one mutation cannot be dismissed as a semantic issue over what constitutes a different fold. As shown in Fig. 1, one conformation consists of a three-helix bundle, whereas the alternate form has a four-strand β-sheet with a single α-helix. Eighty-five percent of residues change their secondary structure, with only eight residues in the central α-helix plus one or two turn residues retaining the same conformation in both forms. When I first heard this result in a public seminar, my mind literally began to reel, leaving me dizzy and slightly nauseated as all hope of understanding how sequence encodes structure seemed to suddenly vanish.

Fig. 1.

The two folds adopted by two amino acid sequences differing only at residue position 45. Corresponding segments of protein chain are given the same color in both structures.

This paper represents the dramatic culmination of a project begun more than 5 years ago (2) involving the systematic modification of two small protein domains taken from a large extracellular protein found in streptococci known as protein G. The fragment referred to as GA is a serum-binding domain, whereas the GB fragment is an IgG-binding domain. Both proteins are soluble, monomeric, and between 45 and 56 aa in length. And both have been extensively studied as model systems by the protein folding community for more than 15 years. Alexander et al. (2) set out to identify the mutational pathway that would convert one protein fold into the other with the fewest unstructured intermediates. The result was a series of sequence pairs, each encoding two stable functional folds, with sequence similarity increasing from essentially zero to differences in amino acid sequence at 20 positions (2), then at 11, 5, 3, and then finally at only 1 position (1). A tyrosine at position 45 specifies the four-strand/one-helix structure, whereas a leucine at this position yields the three-helix bundle.

As described in their paper, many sequence variants were screened by phage display. In a stroke of good fortune, the key functional residues for both proteins could be preserved, allowing the authors to score for the GA conformation by albumin binding and the GB conformation by IgG binding. At each stage in this methodical convergence to a minimal number of sequence differences, the stabilities of the mutant proteins to thermal unfolding were quantified and the “nativeness” of several variants ascertained by analysis of the 15N–1H correlation spectrum, perhaps the best experimental method for detecting molten globule states. In addition, full NMR structures were determined on select variants to remove any doubt about the structural states of sequence pairs.

Because we now live in a world where one amino acid sequence plus one mutation actually can give rise to two very different protein folds, what are the implications? How can we make sense of this observation by putting it into the context of our current understanding of the physical chemistry used by protein sequences to encode structure? And what are its implications for the evolution of protein structure over biological time? Should we expect more examples of dramatic protein fold switching, or is there something exceptional about these two protein domains that diminishes the generality of conclusions we might wish to draw?

First of all, it comes as no surprise that the sequence of a protein can be extensively modified with little or no appreciable effect on structure. Using selection schemes to recover stably folded proteins from mutagenized libraries, it is often possible to substitute 50% or more of residues without changing the fold or greatly lowering the stability (3). Even the kinetics of folding may be little changed from the wild-type values. As one might expect, in such cases most mutant sites are located on the protein surface, where the strength and specificity of interactions are often low. The expected result on going to levels of substitution much higher than 50% would have been destabilization of the folded states, causing much of the sequence pathway connecting the two conformations to be fully unfolded/denatured. But this is not what happened.

As pointed out by Alexander et al. (1), there are precedents in the literature for proteins undergoing changes in their “fold” as result of a few changes in amino acid sequence or cleavage of a peptide bond, although none are as dramatic as the GA/GB switch observed by these authors. In the study of these exceptional cases, the term “chameleon sequence” has been coined to designate those segments of the chain that can undergo a major change in structure given the right stimulus and/or context.

As increasing numbers of protein structures were determined by X-ray crystallography, it became clear that different amino acids displayed different preferences for the three major categories of secondary structure: α-helices, β-strands, and irregular turns/loops (4). That secondary structure is not determined by sequence alone was brought home by finding examples of segments of identical sequences of 5 residues, then 6, then 7, up to 8 residues (5) that had different secondary structures in different tertiary structures. Analysis of the sequences of these chameleon segments indicated they usually consist of both strong helix-forming and strong strand-forming amino acids (6).

Two families of proteins that undergo major irreversible changes in tertiary structure or fold are influenza hemagglutinin and the serpin class of protease inhibitors. In the case of hemagglutinin, an all α-helical homotrimer, the N-terminal α-helix plus ≈20 residues in a loop undergo a large displacement to add to/extend helix 2 (7). In the process, the rearranged helical segments of the three monomers form a long three-helix bundle. In the case of serpins, an extended loop inserts itself as an additional β-strand near the center of a preexisting β-sheet after proteolytic cleavage (8). In both instances the structural change involves residues near a mobile terminus of the protein, with a greater number of contacts being formed in the irreversibly rearranged state.

Other proteins can reversibly change their fold. Under physiological conditions, the cytokine lymphotaxin exists in an equilibrium between a monomer with a three-strand/one-helix topology and a dimer in which the C-terminal helix converts to a loop plus strand that mediates some of the dimer interface (9). Even more remarkable is mad2, a protein involved in mitosis control that alternates between two forms, with a β-hairpin migrating from one end of a β-sheet to the other (10). Because one strand in the hairpin always forms an edge, the hairpin must also undergo a 180° rotation. While the wild-type sequence supports both folds in these two cases, for the dimeric arc repressor, two amino acid substitutions in a β-strand at the C terminus can convert the protein into a monomer, with the β segment becoming α-helical (11).

The N and C termini of folded proteins provide evolution with a variety of opportunities.

The pattern that emerges for analysis of proteins that switch their conformations is that, given the right amino acid sequence, the ends can convert between alternative structural states, one of which is stabilized by a large number of new contacts. The role of protein ends in promoting changes in quaternary structure has been emphasized by Eisenberg as the phenomenon of “3D domain swapping” (12). A terminal strand or helix may peel off and migrate to a second monomer, packing in the same location as it left behind in its own monomer. Dimers and higher-order oligomers can evolve in a single step by this mechanism. In fact, single mutations induce 3D domain swap dimers in a relative of protein G (13), and one set of five conservative mutations leads to a tetramer formed through the exchange of β-strands (14). Taken together, the data suggest that the N and C termini of folded proteins provide evolution with a variety of opportunities for formation of new structures—repositioning and rearrangement of the ends, oligomerization by 3D domain swapping, and sites for accretion of additional amino acids by nonhomologous recombination.

What may be unique in the case of the GA/GB pair is that both ends of the fold, composed of 20–25 residues, switch between alternative conformations. Because the protein is so small, the fraction of residues that change their structure is large. As pointed out by Alexander et al. (1), the N-terminal 8 residues and the C-terminal 5 residues are unstructured in the smaller GA conformation, but form important hydrophobic interactions in the core of the GB conformation. Clearly, the additional stabilizing interactions resulting from packing these residues tightly in the GB conformation play a major role in the conformational switch, because deletion of these residues yields the GA conformation in at least one variant (1). So in one sense, these unstructured residues should be included with the mutation at position 45 in the energy balance sheet at work in the switch between conformations.

For those of us who hope some day to explain the physical chemistry underlying structural phenomena such as shown in Fig. 1, there is some small consolation in the view that more is involved here than the effects of a single side chain. Nevertheless, this paper by Alexander et al. (1) throws into bold relief just how great a challenge remains for developing a complete quantitative understanding of protein structures and their transitions.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 21149.

References

- 1.Alexander PA, He Y, Chen Y, Orban J, Bryan PN. A minimal sequence code for switching protein structure and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21149–21154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906408106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander PA, Rozak DA, Orban J, Bryan PN. Directed evolution of highly homologous proteins with different folds by phage display: Implications for the protein folding code. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14045–14054. doi: 10.1021/bi051231r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim DE, Gu H, Baker D. The sequences of small proteins are not extensively optimized for rapid folding by natural selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4982–4986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou PY, Fasman GD. Prediction of the secondary structure of proteins from their amino acid sequence. Adv Enzymol. 1978;47:45–148. doi: 10.1002/9780470122921.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sudarsanam S. Structural diversity of sequentially identical subsequences of proteins: Identical octapeptides can have different conformations. Proteins. 1998;30:228–231. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19980215)30:3<228::aid-prot2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambroggio XI, Kuhlman B. Design of protein conformational switches. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: The influenza hemagglutinin. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:531–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whisstock JC, Bottomley SP. Molecular gymnastics: Serpin structure, folding and misfolding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:761–768. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuinstra RL, et al. Interconversion between two unrelated protein folds in the lymphotactin native state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5057–5062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709518105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo X, Tang Z, Xia G, Wassmann GK, Matsumoto T, Rizo J, Yu H. The Mad2 spindle checkpoint protein has two distinct natively folded states. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nsmb748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson TA, Cordes MH, Sauer RT. Sequence determinants of a conformational switch in a protein structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18344–18349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509349102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Eisenberg D. 3D domain swapping: As domains continue to swap. Protein Sci. 2002;11:1285–1299. doi: 10.1110/ps.0201402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Neill JW, Kim DE, Johnsen K, Baker D, Zhang KY. Single-site mutations induce 3D domain swapping in the B1 domain of protein L from Peptostreptococcus magnus. Structure. 2001;9:1017–1027. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00667-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirsten Frank M, Dyda F, Dobrodumov A, Gronenborn AM. Core mutations switch monomeric protein GB1 into an intertwined tetramer. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:877–885. doi: 10.1038/nsb854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]