Abstract

Speech production is one of the most fundamental activities of humans. A core cognitive operation involved in this skill is the retrieval of words from long-term memory, that is, from the mental lexicon. In this article, we establish the time course of lexical access by recording the brain electrical activity of participants while they named pictures aloud. By manipulating the ordinal position of pictures belonging to the same semantic categories, the cumulative semantic interference effect, we were able to measure the exact time at which lexical access takes place. We found significant correlations between naming latencies, ordinal position of pictures, and event-related potential mean amplitudes starting 200 ms after picture presentation and lasting for 180 ms. The study reveals that the brain engages extremely fast in the retrieval of words one wishes to utter and offers a clear time frame of how long it takes for the competitive process of activating and selecting words in the course of speech to be resolved.

Keywords: electrophysiology, lexical access, speech production

Word selection is a crucial step in speech production. Considering that the average lexicon contains ≈50,000 lexical entries and that an average speaker utters approximately three words per second, the process of lexical retrieval needs to proceed at high speed and with great accuracy. Failures of this process result in speech errors or anomia, which limit communication, as acutely demonstrated in production aphasia, for instance. Although our understanding of how speakers retrieve words from the lexicon has considerably increased in recent years (1–4), the neural implementation of this process remains poorly understood. In particular, insights regarding the time course of word retrieval in speech production are sparse, and most of the chronometric evidence available is derived from event-related potential (ERP) studies relying on button-press responses rather than in actual overt speech production (5–9). This strategy was adopted because EEG is highly susceptible to mouth movements that could possibly mask the cognitive components of interest. However, at least one EEG study and several MEG studies have shown that artifact-free brain responses can be measured up to at least 400 ms after picture onset (10–13), and a few recent ERP studies demonstrated that classical ERP components can be replicated during overt picture naming (14–17).

Although these latter studies reveal the validity of ERPs for studying overt naming, they have not directly investigated the issue of the time course of lexical selection, but rather other aspects of word production (e.g., morphological processing, bilingual language control, etc.). It is the goal of the present study to identify the time course of word selection during overt naming, capitalizing on the fine temporal resolution of ERPs. In this study, we directly measure the time course of word retrieval during overt naming. Such temporal information is invaluable for understanding brain mechanisms underlying speech production and to elucidate the causes of speech failure. Additionally, this approach may offer a framework to constrain theoretical models of language production.

With this aim in mind, we chose to exploit the cumulative semantic interference effect (CSIE) (18) as a proxy for lexical selection in picture naming. In this paradigm, participants name a set of pictures from intermixed semantic categories (e.g., turtle, hammer, tree, crocodile, bus, axe, snake, etc.). Interestingly, naming latencies for a given picture (e.g., snake) increases linearly with its ordinal position within the semantic category. That is, the naming latency for a given item correlates positively, linearly, and highly with the number of items from the same semantic category that have been named previously (e.g., turtle, crocodile).

It has been debated whether this striking effect reflects competition at a semantic or a lexical level (18–23). According to the semantic account, the effect arises at the level at which semantic representations are being selected for production. The idea is that semantically related conceptual representations compete with one another, such that the reactivation of previously selected representations hinders the speed with which the semantic representation corresponding to the target picture is singled out and selected for further processing (22, 23). According to the lexical interpretation, the interference between semantic competitors is assumed to reflect the difficulty in selecting a specific lexical item produced by the reactivation of lexical items of the same semantic category that have been produced previously: The more items of the same semantic category are encountered, the higher the amount of competition when selecting another item (the target one) from the same semantic category. Although there is still debate about the specific origin of the effect, several fMRI and MEG studies have consistently shown increased activation during semantic competition in the middle temporal gyrus and the left inferior frontal gyrus (12, 24–28), two regions putatively associated with lexical access and selection (29–31).

Knowledge of the timing of ERP effects elicited by the CSIE is likely to provide key temporal information on lexical selection during picture naming. More specifically, we predict that there should be a time window in which the ERPs correlate positively with the ordinal position of the target within the series of pictures belonging to the same semantic category. To the extent that the CSIE reveals the processes engaged during word selection, such a window can be considered as the time interval in which word retrieval takes place.

There are two independent studies that allow for a precise prediction about the time at which word retrieval from the lexicon occurs. First, according to the meta-analysis conducted by Indefrey and Levelt (29), lexical selection will unfold between 175 and 250 ms after picture onset. Second, a recent study has shown that lexical frequency effects start modulating ERPs between 180–190 ms after target presentation during overt picture naming (32). Hence, we expect that (i) the CSIE should begin to affect ERP amplitudes between 175 and 250 ms after picture onset in the present experiment and (ii) ERP amplitudes elicited by pictures to be named should correlate positively with the ordinal position of the pictures within their semantic category group.

Results

Naming Latencies.

Voice key errors (2%), naming errors (6.7%), and outliers (three standard deviations above or below the participant's mean; 5.2%) were removed from analyses. Separate subject (F1) and item (F2) analyses were carried out, examining two independent variables: ordinal position (5) and block (3).

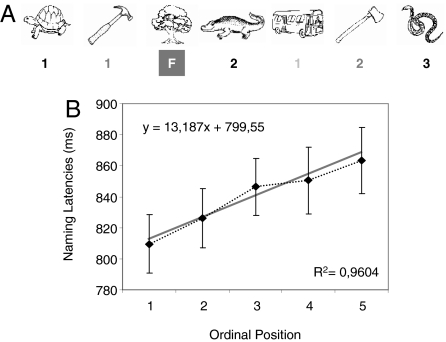

Naming latency results for each ordinal position are depicted in Fig. 1. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed a significant main effect of ordinal position [F1 (4, 92) = 22.37, MSE = 2,008.65, P < 0.001; F2 (4, 92) = 10.96, MSE = 3,065.19, P < 0.001] and a significant block effect [F1 (2, 46) = 12.97, MSE = 2,422.74, P < 0.001; F2 (2, 46) = 25.81, MSE = 3,900.88, P < 0.001]. The ordinal position × block interaction was not significant (all P values > 0.3). Furthermore, a highly significant positive correlation between ordinal position and naming latencies was observed (R2 = 0.96, P = 0.003).

Fig. 1.

Design and behavioral results of the CSIE. (A) Design and some exemplar stimuli used in the present experiment. Numbers (1, 2, or 3) refer to the ordinal position at which a member of a semantic category is presented; F refers to filler. (B) Naming latencies in milliseconds at each ordinal position.

Event-Related Potentials.

Pictures elicited an expected P1/N1/P2 ERP complex in all conditions. In the 0- to 180-ms time window (P1 and N1 range), no ordinal position and block effects were observed (all P values > 0.1).

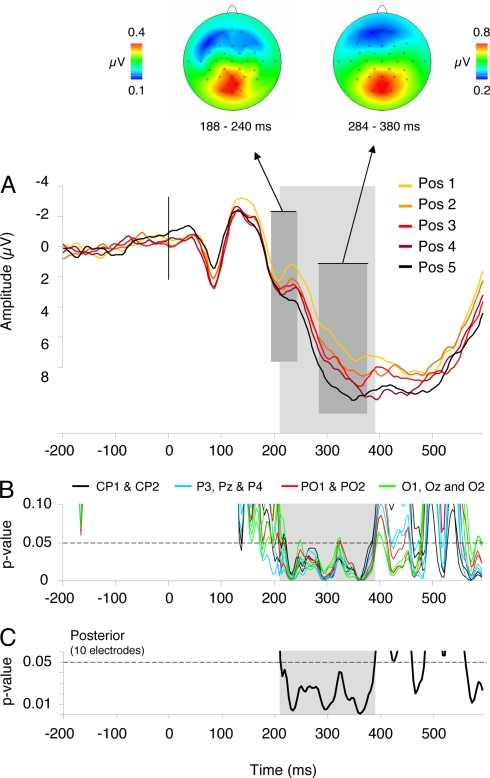

In the P2 range, ordinal position, block, and the interaction effects between the two factors were not significant (all P values > 0.1). The ordinal position × cluster interaction was significant (F = 1.74, MSE = 3.19, P = 0.007). Analyses per cluster revealed a significant ordinal position effect over the left parietal, right parietal, and occipital regions (all P values < 0.03; cf. Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

ERP results and correlation analyses of the CSIE. (A) ERPs elicited by the five ordinal positions within the semantic categories. The waveforms depicted are the linear derivation of the 10 posterior electrodes where significant effects were present (CP1, CP2, P3, Pz, P4, PO1, PO2, O1, Oz, O2). The dark gray area refers to the P2 peak and P3 peak showing a linear and cumulative increase in amplitude with each ordinal position. Above the topographic maps of the averaged differences waves of the five ordinal positions for the P2 and P3 are shown. The light gray area refers to the time frame (208–388 ms) where ERP amplitudes correlated with ordinal position and RTs. (B) Significance graph of the correlation analyses at each sampling rate (4 ms) between RTs and ERP amplitudes at the five ordinal positions for the 10 posterior electrodes. (C) Significance graph of the correlation analyses at each sampling rate (4 ms) between RTs and ERP amplitudes at the five ordinal positions averaged over the 10 posterior electrodes. Correlations were reliably below the 0.05 significance level between 208 and 388 ms after picture presentation (light gray area).

In the N2 range, the main effect of block and the ordinal position × block interaction did not reach significance (P values > 0.1). In contrast, the effect of ordinal position (F = 2.57, MSE = 263.44, P = 0.04) and the ordinal position × cluster interaction (F = 3.00, MSE = 6.51, P < 0.001) were significant. Analyses per cluster revealed significant ordinal position effects over left central, parietal, and occipital regions (all P values < 0.03).

In the P3 range, the main effect of block and the ordinal position × block interaction failed to reach significance (Ps > 0.1). In contrast, the effect of ordinal position (F = 3.27, MSE = 439.51, P = 0.01) and the ordinal position × cluster interaction (F = 2.18, MSE = 4.86, P < 0.001) were significant. Analyses per cluster revealed significant ordinal position effects over left and right central, parietal, and occipital regions (all P values < 0.03).

Finally, the main effect of ordinal position (F = 2.61, MSE = 475.31, P = 0.04) and the main effect of block (F = 4.75, MSE = 1,195.68, P = 0.01) were significant in the N400 range. However, the ordinal position × cluster and ordinal position × block interactions were not significant (all P values > 0.1).

In addition, highly significant positive correlations were found between mean ERP amplitudes and naming latencies for the P2 (R2 = 0.90, P = 0.014), the N2 (R2 = 0.93, P = 0.008), and the P3 (R2 = 0.96, P = 0.003) peaks. We also observed highly significant positive correlations between mean ERP amplitudes and ordinal position for the P2 (R2 = 0.87, P = 0.021), the N2 (R2 = 0.93, P = 0.009), and the P3 (R2 = 0.97, P = 0.002) peaks. Neither of these correlation types remained significant in the N400 range (mean amplitude versus naming latencies: R2 = 0.66, P = 0.09; mean amplitude versus ordinal position: R2 = 0.72, P = 0.07).

Peak latency analyses revealed no block and no ordinal position effects and no interaction in any of the five time windows of interest (all P values > 0.1).

Point-by-Point Correlations Between ERP Amplitudes and RTs.

We calculated point-by-point correlations over ordinal positions between the RTs and ERP amplitudes every 4 ms (i.e., at the resolution of acquisition sampling rate) to track the time course of the CSIE in the ERPs. We limited this analysis to the 10 posterior electrodes where significant ERP amplitude modulations by ordinal position were significant. RTs at each ordinal position started to correlate reliably with ERP amplitudes 208 ms after picture onset, and correlations remained significant until 388 ms after picture onset (Fig. 2 B and C). To ensure that the duration of the CSIE in the ERPs (180 ms) was not primarily due to latency jitter, we calculated the correlations between the peak latencies of the three ERP peaks (P2, N2, P3), where significant effects were present (32). None of these correlations turned out to be significant (all P values > 0.1).

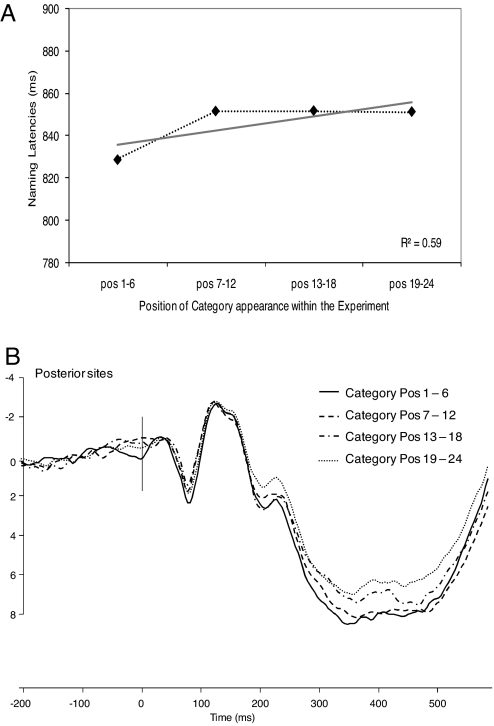

Further correlation analyses were conducted on RTs and ERP amplitudes to determine whether the observed effects were indeed due to the CSIE and not to the overall presentation order within the experiment. We hypothesized that neither the correlation between RTs and ordinal between-category positions nor the correlation between ERP amplitudes and ordinal between-category positions would be significant (see Methods). As predicted, neither correlations were significant (all P values > 0.1). Finally, neither the RTs (Fig. 3A) nor the ERPs (Fig. 3B) correlated significantly with ordinal between-category positions when averaging together the five ordinal within-category positions for each between-category position (both P values > 0.08).

Fig. 3.

Behavioral and ERP results of the between-category order of appearance within the experiment. (A) Naming latencies in milliseconds at four ordinal positions of category appearance within the experiment (averaged across categories taken six-by-six). (B) ERPs elicited by the four ordinal positions of category appearance within the experiment (averaged across categories taken six-by-six). The waveforms depicted are the linear derivation of the same 10 posterior electrodes as those in Fig. 2.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the electrophysiological correlates of the CSIE during overt picture naming to characterize the time course of word retrieval in language production. First, we replicated the CSIE reported by Howard et al. (18) and showed that this effect survives several repetitions of the same picture in different experimental blocks (Fig. 1). Second, the earliest electrophysiological modulation induced by the CSIE, as indexed by positive correlations between naming latencies and ERP amplitudes for the five ordinal positions of pictures within their semantic category was found at 208 ms and remained until 388 ms after picture onset (Fig. 2). Peak latency correlation analyses between the peaks where significant effects were found (see below) revealed that it is unlikely that the duration of these positive correlations (180 ms) were smeared out because of latency jitter. Third, three ERP peaks were significantly modulated by the CSIE effect: P2, N2, and P3 amplitudes correlated positively with: (i) The ordinal position of the picture within the stream of pictures belonging to the same semantic category and (ii) individual naming latencies at each ordinal position. There was also a significant effect of ordinal position in the N400 range, but N400 amplitudes failed to correlate significantly with ordinal position or naming latencies. Finally, we showed that the results obtained for the CSIE, both behavioral and electrophysiological, cannot be accounted for by the order of appearance of items across the whole experiment (Fig. 3).

Assuming that the CSIE indexes the difficulty with which lexical items are retrieved from the lexicon, the onset of significant correlations in this experiment can be taken as evidence that the brain engages in lexical selection at ≈200 ms after picture onset. This implies that by that time, access to the picture's semantic representation should be sufficiently fine-grained to initiate the search for specific lexical items. This result is consistent with a number of previous findings, e.g., the fact that semantic analyses of a picture enfolds during the first 150–200 ms after its onset (33) and those revealing the onset of lexical frequency and cognate effects at ≈180 ms after picture onset during picture naming (32).

Our observations are consistent with the time window of lexical selection (175–250 ms) put forward by Indefrey and Levelt (29), even though, in this meta-analysis, the average response time of participants was in the region of 600 ms. Interestingly, in a previous study (32), we found an onset latency for lexical access (180–190 ms) in the temporal vicinity of the latency observed in the present study, while RTs were in the region of 700 ms (140 ms faster as observed here). Therefore, it appears that the onset of lexical access varies little (175–200 ms) regardless of the naming response times of participants or the amount of stimuli and repetitions used in the naming task. Thus, the onset of lexical access seems relatively independent of the speed with which lexical items are produced. This implies that the difference in production latency between different lexical items arises mainly after lexical access has taken place, i.e., during later stages of lexical and postlexical processing likely sensitive to task difficulty and psycholinguistic variables such as frequency, length, age of acquisition, etc.

Importantly, our results are not only relevant for determining when the lexicon is accessed, but also for the duration of lexical selection processes. The correlation between CSIE and ERP amplitudes lasted 180 ms after it became significant at 208 ms. If one considers the CSIE as indexing the difficulty of lexical retrieval, it can be assumed that lexical competition continues until the correlations disappear. Our estimation of 180 ms for the time needed to retrieve a target word from the lexicon is larger than: (i) the 75-ms estimate put forward by Indefrey and Levelt (29); (ii) the 110 ms derived from modeling of dual-task picture-word interference data (34); and (iii) the 80 ms reported in a previous go/no-go ERP study (35). Although, it is difficult to determine the origin of these differences, given the very different tasks used, we can advance two potential explanations for this discrepancy. First, the CSIE may actually spill over to other processes downstream from lexical retrieval, such as phonological encoding (see cascade and interactive models of word retrieval; 1, 2), which may have extended the duration of correlations measured in our experiment (note that this may also have happened in the other studies mentioned above). Second, the amount of time separating the onset of lexical access from actual lexical selection may not be invariable, but, on the contrary, dependent upon the amount of interference within the lexical system during the process (among other variables). Given the nature of the CSIE, which increases in magnitude with the increasing number of competitors, it is likely that in our study the lexicalization process was prolonged in comparison to the previous studies. This means that the temporal window of 180 ms should be reduced if we were to consider the first two or three ordinal positions rather than all five. Unfortunately, the design of our experiment does not allow for such comparison, since splitting the ordinal positions (e.g., the first three and the last two) reduces statistical power considerably and makes the calculation of correlation scores invalid.

Nonetheless, these questions are empirical ones which will require future investigations. The key contribution here is that we identified a temporal framework where semantically related words induce competition within the linguistic system. In fact, precisely this time window offers a unique way to explore the conditions that may affect word retrieval and test the different processing dynamics (serial, cascade, or parallel) put forward in different language models (1–4).

In a more conventional analysis of our data, we also found a strong positive correlation between naming latencies and the mean amplitude of three ERP peaks (P2, N2, P3). These correlations support the view that these ERP peaks, or at least the P2, are sensitive to the difficulty with which lexical selection proceeds (32). Further research will need to determine both the functional characteristics of these components [e.g., attention (36), mental effort (10), inhibition (37)] and whether they index different cognitive processes. Nonetheless, our correlation approach has the advantage of doing away with traditional component-based analyses and reveals a functional relationship between ERP amplitude and a specific cognitive process at every sampling point after the onset of a stimulus.

Finally, the present data shed light on the issue of whether the locus of the CSIE is semantic or lexical in nature. Indeed, the time frame in which we observed electrophysiological correlates of the CSIE does not readily correspond with the time frame traditionally associated with semantic analysis (i.e., 0–150 ms) (7, 12, 29). Furthermore, correlates of the CSIE were found from 208 ms onwards and are therefore compatible with the time window associated with lexical retrieval in the study by Strijkers et al. (32). In that study, a P2 modulation was elicited by lexical frequency differences between two sets of pictures, by the cognate status of picture names, and even by the language in which picture naming was required. This evidence, combined with that from neuroimaging presented in the introduction, are strong arguments in favor of a lexical locus for the CSIE rather than a semantic one. This finding suggests that lexical access may entail competitive processing (38, 39).

In sum, our study shows that lexical retrieval during overt speech production is a fast process starting ≈200 ms after presentation of a picture and unfolds for 180 ms. This fine-grained time course information is an important step toward a temporal map of speech production. Such a map will provide valuable insights for understanding this remarkable human ability as well as help us to clarify why speech is impaired in brain damaged patients and individuals with developmental disorders.

Methods

Participants.

Twenty-four undergraduate students at the University of Barcelona and native speakers of Spanish participated in the experiment (ages 18–25). All were right-handed, had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and did not suffer from motor or neurological problems.

Stimuli and Procedure.

The design and materials were practically identical to those used in Howard et al. (18) (see Fig. 1A for an example). One hundred sixty-five different pictures, consisting of 120 target items (five exemplars for each of 24 semantic categories) and 45 fillers, were used (see SI Appendix). Twenty-four experimental lists were created with the constraints that no target could appear in the first five positions (practice), and targets from the same category were randomly separated by at least two and maximum seven items. Intervening items could either be fillers (25%) or targets from other semantic categories (75%). Semantic categories were rotated, so that across participants they appeared once in each of the possible 24 orderings. There were four main differences with respect to Howard et al.'s design (18): (i) We used black and white line drawings (40, 41) instead of colored pictures. (ii) Items within a category were semirandomized, such that across participants each exemplar appeared at least four times in each possible ordinal position (leaving only 3.33% position variability between exemplars) to ensure ERP modulations were not elicited by physical differences between stimuli. (iii) Lag position (from 2–7) was assigned randomly. (iv) Each participant was presented with three different experimental lists to ensure sufficient trials for ERP averaging. Each experimental trial had the following structure: (i) a blank interval of 1,000 ms was shown at the center of a computer screen; (ii) a picture was displayed at the center of the screen until a response was given or for a maximum of 1,500 ms; (iii) a blank intertrial interval of 1,000 ms intervened before the next trial started. An asterisk was presented for 500 ms before the first trial and after the last trial to signal the beginning and end of each list. Lists were separated by a 30-s pause.

EEG Procedure.

EEGs were recorded from 31 scalp locations, two bipolar electrodes above and beneath the left eye recorded eye movements, and an electrode placed on the participant's nose was used as reference channel. The EEG was continuously recorded and digitized at 250 Hz. Impedances were reduced to 3 kOhms or less before the beginning of recording. The EEG data were low- and high-pass filtered (20 to 0.03 Hz) and afterward segmented into 800-ms epochs (−200 to 600 ms). Before averaging, trials with a naming response faster than 600 ms (2.4%) were removed to avoid contamination of the ERPs due to muscular and mouth movement activity and differential latency jitter between conditions (32). Also, segments containing artifacts (brain activity >100 or below −100 mV) were removed before averaging. The 800-ms epochs were averaged in reference to the 200-ms prestimulus baseline.

ERP Analysis.

Three types of analyses were conducted on the ERP data. First, classical peak amplitude and latency analyses were run to observe which ERPs were sensitive to the lexical manipulation (indexing lexical selection). Seven time windows containing visible ERP peaks were selected for mean amplitude analysis: [0; 50], [70; 120] (P1 peak), [130; 180] (N1), [190; 240] (P2), [230; 280] (N2), [280; 380] (P3), and [380; 480] ms (N400). Furthermore, electrodes were grouped into nine clusters dividing the scalp in anterior, central, posterior, and left, midline, and right sites. A five (ordinal position) × three (block) × nine (cluster) repeated-measures ANOVA was performed on the ERP data.

Second, we conducted point-by-point correlation analyses over the five ordinal positions of pictures within each semantic category between the mean RTs and mean ERP amplitudes over the entire group of participants every 4 ms to track the time course of the CSIE in the ERPs. A time window was considered significant when at least 15 consecutive significant correlations (P < 0.05) between the ERPs and the RTs were obtained (i.e., for at least 60 ms) (42, 43). We took the first time point of an uninterrupted series of at least 15 significant correlations as the onset of the CSIE effect.

Third, to test for a potential confound of order of target appearance in the experiment as a whole (as opposed to within a semantic category), we divided each category according to its order of appearance in the experiment. That is, for each experimental list, we calculated which category came first in the list, second in the list, third in the list, and so on for all 24 categories. This gave us a total of 24 ordinal between-category positions within the experiment; an ordinal between-category position was averaged across the five items belonging to that particular category, since a category that started (the picture presentation of the first member of that category) before another category, also always ended (picture presentation of the fifth member of that category) before the other category. To increase statistical power, we then averaged those 24 ordinal between-category positions across categories taken six-by-six (the first six, those appearing in positions seven to 12, those appearing at positions 13 to 18, and the last six), which resulted in four ordinal category positions of appearance within the experiment overall. In other words, we ended up with four ordinal positions of between-category appearance, calculated over the same items as for the CSIE, but without containing any semantic relationship between the positions (as it is for the CSIE) and only containing a difference in when during the experiment (beginning, middle, or end) they appear.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Elin Runnqvist and Nuria Sebastián for their helpful comments and discussion at different stages of this work. This work was supported by a grant from the Spanish Government (PSI2008–01191) and the Project Consolider-Ingenio 2010 (CSD 2007–00012). K.S. is supported by a Predoctoral fellowship from the Spanish Government (FPU 2007–2011). C.M. was supported by a Postdoctoral fellowship from the Spanish Government (CSD 2007–00012). G.T. is supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (ES/E024556/1) and the European Research Council (ERC-SG-209704).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0909089106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Caramazza A. How many levels of processing are there in lexical access? Cognit Neuropsychol. 1997;14:177–208. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dell GS. A spreading-activation theory of retrieval in sentence production. Psychol Rev. 1986;93:283–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levelt WJM, Roelofs A, Meyer AS. A theory of lexical access in speech production. Behav Brain Sci. 1999;22:1–75. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99001776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pulvermüller F. Words in the brain's language. Behav Brain Sci. 1999;22:253–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hauk O, Rockstroh B, Eulitz C. Grapheme monitoring in picture naming: An electrophysiological study of picture naming. Brain Topography. 2001;14:3–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1012519104928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiller NO, Bles M, Jansma BM. Tracking the time course of phonological encoding in speech production: An event-related brain potential study. Brain Res. 2003;17:819–831. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(03)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmitt BM, Münte TF, Kutas M. Electrophysiological estimates of the time course of semantic and phonological encoding during implicit picture naming. Psychophysiology. 2000;37:473–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Turennout M, Hagoort P, Brown CM. Electrophysiological evidence on the time course of semantic and phonological processes in speech production. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1997;23:787–806. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.23.4.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Turennout M, Hagoort P, Brown CM. Brain activity during speaking: From syntax to phonology in 40 milliseconds. Science. 1998;280:572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eulitz C, Hauk O, Cohen R. Electroencephalographic activity over temporal brain areas during phonological encoding in picture naming. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111:2088–2097. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levelt WJM, Praamstra P, Meyer AS, Helenius P, Salmelin R. A MEG study of picture naming. J Cogn Neurosci. 1998;10:553–567. doi: 10.1162/089892998562960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maess B, Friederici AD, Damian M, Meyer AS, Levelt WJM. Semantic category interference in overt picture naming: An MEG study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14:455–462. doi: 10.1162/089892902317361967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salmelin R, Hari R, Lounasmaa OV, Sams M. Dynamics of brain activation during picture naming. Nature. 1994;368:463–465. doi: 10.1038/368463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christoffels IK, Firk C, Schiller NO. Bilingual language control: An event-related brain potential study. Brain Res. 2007;1147:192–208. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganushchak LY, Schiller NO. Motivation and semantic context affect brain error-monitoring activity: An event-related brain potentials study. NeuroImage. 2008;39:395–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koester D, Schiller N. Morphological priming in overt language production: Electrophysiological evidence from Dutch. NeuroImage. 2008;42:1622–1630. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verhoef K, Roelofs A, Chwilla JC. Role of inhibition in language switching: Evidence from event-related brain potentials in overt picture naming. Cognition. 2009;110:84–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howard D, Nickels L, Coltheart M, Cole-Virtue J. Cumulative semantic inhibition in picture naming: Experimental and computational studies. Cognition. 2006;100:464–482. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damian MF, Vigliocco G, Levelt WJM. Effects of semantic context in the naming of pictures and words. Cognition. 2001;81:B77–B86. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(01)00135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monsell S, Matthews GH, Miller DC. Repetition of lexicalisation across languages: A further test of the locus of priming. Q J Exp Psychol. 1992;44A:763–783. doi: 10.1080/14640749208401308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wheeldon L, Monsell S. Inhibition of spoken word production by priming a semantic competitor. J Mem Lang. 1994;3:332–356. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lupker SJ, Katz AN. Input, decision and response factors in picture-word interference. J Exp Psychol Hum Learn Mem. 1981;7:269–282. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rayner K, Springer CJ. Graphemic and semantic similarity effects in the picture-word interference task. Brit J Psychol. 1986;77:207–222. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1986.tb01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abel, et al. The separation of processing stages in a lexical interference fMRI-paradigm. NeuroImage. 2009;44:1113–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Zubicaray GI, Wilson SJ, McMahon KL, Muthiah S. The semantic interference effect in the picture-word paradigm: An event-related fMRI study employing overt responses. Hum Brain Mapp. 2001;14:218–227. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Zubicaray GI, McMahon KL, Eastburn MM, Wilson SJ. Orthographic/phonological facilitation of naming responses in the picture-word task: An event-related fMRI study using overt vocal responding. NeuroImage. 2002;16:1084–1093. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schnur TT, Schwartz MF, Kimberg DY, Hirshorn E, Coslett HB, Thompson-Schill SL. Localizing interference during naming: Convergent neuroimaging and neuropsychological evidence for the function of Broca's area. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805874106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spalek K, Thompson-Schill SL. Task-dependent semantic interference in language production: An fMRI study. Brain Lang. 2009;107:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Indefrey P, Levelt WJM. The spatial and temporal signatures of word production components. Cognition. 2004;92:101–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2002.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hickok G, Poeppel D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:393–402. doi: 10.1038/nrn2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lau E, Phillips C, Poeppel D. A cortical network for semantics: (De)constructing the N400. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;9:920–933. doi: 10.1038/nrn2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strijkers K, Costa A, Thierry G. Tracking lexical access in speech production: Electrophysiological correlates of word frequency and cognate effects. Cereb Cortex. 2009 Aug 13; doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thorpe S, Fize D, Marlot C. Speed of processing in the human visual system. Nature. 1996;381:520–522. doi: 10.1038/381520a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levelt, et al. The time course of lexical access in speech production: A study of picture naming. Psychol Rev. 1991;98:122–142. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmitt BM, Schiltz K, Zaake W, Kutas M, Munte TF. An electrophysiological analysis of the time course of conceptual and syntactic encoding during tacit picture naming. J Cogn Neurosci. 2001;13:510–522. doi: 10.1162/08989290152001925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luck SJ, Hillyard SA. Electrophysiological correlates of feature analysis during visual search. Psychophysiology. 1994;31:291–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb02218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pulvermuller F, Lutzenberger W, Birbaumer N. Electrocortical distinction of vocabulary types. Electroenceph Clin Neurophysiol. 1995;94:357–370. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(94)00291-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finkbeiner M, Caramazza A. Now you see it, now you don't: On turning semantic interference into facilitation in a stroop-like task. Cortex. 2006;42:790–796. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahon BZ, Costa A, Peterson R, Vargas K, Caramazza A. Lexical selection is not by competition: A reinterpretation of semantic interference and facilitation effects in the picture-word interference paradigm. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2007;33:503–535. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.33.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alario F-X, Ferrand L. A set of 400 pictures standarized for French: Norms for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity, visual complexity, image variability, and age of acquisition. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 1999;31:531–552. doi: 10.3758/bf03200732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Snodgrass JG, Vanderwart M. A standardized set of 260 pictures: Norm for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity, and visual complexity. J Exp Psychol Hum Learn Mem. 1980;6:174–215. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.6.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guthrie D, Buchwald JS. Significance testing of difference potentials. Psychophysiology. 1991;28:240–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1991.tb00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thierry G, Cardebat D, Demonet JF. Electrophysiological comparison of grammatical processing and semantic processing of single spoken nouns. Brain Res. 2003;17:535–547. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(03)00168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.