Abstract

Background: The proliferative index (PI) is a powerful prognostic factor in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL); however, its utility is hampered by interobserver variability. The mantle cell international prognostic index (MIPI) has been reported to have prognostic importance. In this study, we determined the prognostic value of the PI as determined by quantitative image analysis in MCL.

Patients and methods: Eighty-eight patients with adequate tissue were included in this analysis. Patients were treated with one of two treatment programs: sequential therapy with high-dose therapy consolidation or radioimmunotherapy followed by combination chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone. Patients were divided into four groups based on PI (<10%, 10%–29.9%, 30%–49.9%, and >50%), and outcomes were analyzed.

Results: Thirty percent was identified as the optimal cut-off for PI. By univariate analysis, intensive treatment and a low PI were associated with a superior progression-free survival (PFS); only PI was associated with overall survival. By multivariate analysis, both intensive treatment and PI correlated with PFS. The MIPI had no prognostic impact.

Conclusions: PI is the most important prognostic factor in MCL. The cut-off of 30% is clinically meaningful and can be used to tailor the intensity of therapy in future clinical trials.

Keywords: mantle cell lymphoma, prognosis, proliferative index, quantitative image analysis

introduction

The management of patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) lacks an accepted standard of care. CHOP (combination chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisone) or CHOP-like chemotherapy regimens are associated with a median overall survival (OS) between 3 and 5 years [1–3]. Adding rituximab to CHOP (R-CHOP) or fludarabine-based chemotherapy has improved the overall response, but progression-free survival (PFS) and OS are not improved [4, 5]. Intensive regimens have been evaluated including fractionated cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, dexamethasone alternating with high-dose methotrexate—cytarabine (R-HyperCVAD/R-MA) and sequential chemotherapy followed by consolidation with high-dose therapy and autologous stem-cell rescue (HDT/ASCR) [6, 7]. For those patients who could tolerate more intensified treatment regimens, event-free survival and OS at 5–6 years improves to 48%–56% and 65%–70%, respectively [7, 8]. In contrast, some advocate a less intensive ‘watch and wait’ approach to MCL, with treatment when clinically indicated [9]. A better understanding of MCL prognostic factors would identify patients for whom intensified treatment is most appropriate. Currently, the best defined prognostic factors are the proliferative index (PI) and the mantle cell international prognostic index (MIPI).

Several studies have demonstrated that PI estimated by immunohistochemistry (IHC) for Ki-67 predicts clinical outcome. The PI inversely correlates with OS irrespective of treatment type [7, 10–18]. However, the method of determining PI by IHC has varied from a semiquantitative estimation to direct counting of 1000 cells per case. Different groups have reported variable cut-offs between 10% and 60% [7, 10–12, 14, 16–18]. This variability likely arises at least in part from interobserver variation in the interpretation of IHC for Ki-67.

MIPI is a better predictor of OS than the International Prognostic Index in a population treated with a variety of approaches including anthracycline-based chemotherapy with or without rituximab, as well as some patients undergoing consolidation with HDT/ASCR [19]. However, the simplified mantle cell international prognostic index (sMIPI) did not predict outcome for patients treated with R-HyperCVAD/R-MA [20].

Thus, both PI estimated by Ki-67 IHC and the MIPI have limitations in the prognostication of MCL. In this study, a highly reproducible computer-based quantitative image analysis (QIA) was employed to overcome the interobserver variability in determining PI. We sought to determine a cut point for PI that could distinguish outcome in patients with MCL. Furthermore, we sought to determine the prognostic value of the MIPI, sMIPI, and Ki-67-MIPI.

patients and methods

One hundred and eleven patients with a new diagnosis of MCL between 1998 and 2008 participated in a treatment plan of sequential therapy with four cycles of CHOP-14 ± rituximab induction followed by two or three cycles of ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide) ± rituximab chemotherapy [(R)ICE]. The number of cycles of (R)ICE chemotherapy was determined by functional imaging after induction. Patients underwent consolidation with HDT with combination of carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine and melphalan followed by ASCR. Between April 2001 to December 2004, 24 patients were included in a prospective study of sequential 131I-tositumomab followed by six cycles of CHOP-21 [radioimmunotherapy (RIT-CHOP)] [21]. The diagnosis of MCL was confirmed by review of diagnostic biopsies. A total of 88 patients with adequate tissue were included in the analysis (69 from the HDT/ASCR group and 19 from the RIT-CHOP group). This study was approved by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board under a waiver of authorization.

MIPI

The MIPI, MIPI combined with Ki-67, and the sMIPI were determined as originally described [19].

immunohistochemistry

Eighty-eight patients had formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue available for IHC for Ki-67 staining using the MIB1 mouse mAb (Immunotech, Westbrook, ME) at a 1:500 dilution. Standard avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex techniques were used for IHC carried out on 5-μm sections of FFPE tissue. Antigen retrieval in heated citrate buffer at pH 6.0 was applied for all antibodies. Positive control tissues were stained in parallel with the study cases. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin.

quantitative image analysis

Ki-67-stained slides were scanned with the Aperio ScanScope XT (Aperio, Vista, CA) using a (20 objective. Whole slide images were analyzed with the Aperio nuclear IHC algorithm. Briefly, brown (3,3-diaminiobenzidine) and blue (hematoxylin) colors were separated spectrally. Blue cells that were also brown were scored as positive, and cells that were blue only were scored as negative. The percentage of positive cells was calculated as brown divided by the sum of brown and blue cells. The QIA algorithm counted a median of 571 358 cells per slide (1504–5 476 582).

cut-off determination

The sample size was not large enough to independently determine a clinically relevant cut point for the PI. We chose to validate the PI cut-offs of 10% and 30% as proposed by Determan et al. [10] and used in Geisler et al. [7]. Moreover, we tested a 50% cut-off to explore the impact of a higher PI on survival.

statistical analysis

Patient outcomes were evaluated by intention to treat. Patients who received any of the planned treatment (CHOP-14 for the HDT/ASCR group or radioimmunotherapy for the RIT-CHOP group) were included regardless of completing treatment. OS was calculated from diagnosis until death from any cause or the last follow-up visit. PFS was determined from the beginning of the treatment until progression, relapse, death from any cause, or last follow-up visit. Categorical data were analyzed by the chi-square test and continuous data by the Mann–Whitney test. Survival curves are per the method of Kaplan–Meier; comparative analyses were carried OUT by log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used for the multivariate analysis. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

results

Patient characteristics (N = 88) are shown in Table 1, with a comparison of the HDT/ASCR and RIT-CHOP treatment groups. There was an expected male predominance (76%). The median age was 57 years (range 34–77 years); patients in the RIT-CHOP group were significantly older. Lactose dehydrogenase was abnormal in 26 of 84 available patients (31%). Bone marrow disease was present in 62 (71%) patients. The majority had advanced-stage disease (stage III 8%; IV 77%). The MIPI and its variants were balanced between treatments. The PI was higher in patients receiving HDT/ASCR (median 29% versus 17%, P = 0.002).

Table 1.

Comparison of treatment groups

| Characteristics | Intensive therapya (N = 69), No (%) | RIT-CHOPb (N = 19), No. (%) | Pc |

| Age, years | 0.01 | ||

| <60 | 49 (71) | 7 (37) | |

| ≥60 | 20 (29) | 12 (63) | |

| LDH | 0.40 | ||

| Normal | 43 (66) | 15 (79) | |

| High | 22 (34) | 4 (21) | |

| NA | 04 | 0 | |

| Performance status (ECOG) | 0.68 | ||

| 0–1 | 60 (88) | 18 (95) | |

| 2 | 8 (12) | 1 (5) | |

| NA | 1 | 0 | |

| Ann Arbor stage | 0.99 | ||

| I or II | 3 (4) | 0 | |

| III or IV | 66 (96) | 19 (100) | |

| Bone marrow involvement | 0.09 | ||

| No | 17 (25) | 9 (47) | |

| Yes | 52 (75) | 10 (53) | |

| MIPI | 0.98 | ||

| Low | 34 (55) | 10 (53) | |

| Intermediate | 18 (29) | 6 (32) | |

| High | 10 (16) | 3 (16) | |

| NA | 7 | ||

| sMIPI | 0.28 | ||

| Low | 33 (52) | 9 (47) | |

| Intermediate | 20 (31) | 9 (47) | |

| High | 11 (17) | 1 (6) | |

| NA | 5 | ||

| MIPI-Ki-67 | 0.30 | ||

| Low | 11 (19) | 3 (16) | |

| Intermediate | 29 (49) | 13 (68) | |

| High | 19 (32) | 3 (16) | |

| NA | 10 | – | |

| Ki-67, % | 0.06 | ||

| <10 | 15 (22) | 7 (37) | |

| 10–29.9 | 23 (33) | 10 (53) | |

| 30–49.9 | 17 (25) | 1 (5) | |

| ≥50 | 14 (20) | 1 (5) |

R-CHOP-14 + (R)ICE + autologous stem-cell transplant.

Tositumomab followed by CHOP.

Chi-square test.

RIT-CHOP, radioimmunotherapy + CHOP; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, prednisone; LDH, lactose dehydrogenase; NA, not available; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; MIPI, mantle cell international prognostic index; sMIPI, simplified MIPI; R-CHOP, rituximab to CHOP; (R)ICE, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide) ± rituximab chemotherapy.

Sixty-nine patients were treated according to the intensive protocol, and 64 were submitted to autogeneic stem-cell transplantation (93%). The reasons for not proceeding to HDT/ASCR were disease progression (one), allogeneic SCT (one), heart disease (one), renal disease (one), and one death from sepsis during ICE.

survival analysis

The median follow-up of surviving patients was 4.8 years (1.0–11.5 years). Thirty-seven patients relapsed, and 20 died during this period. The median PFS was 5 years; the median OS has not been reached (5-year OS 76%). There was no difference in PFS or OS with respect to rituximab use in the patients undergoing HDT/ASCR (4-year PFS 58% versus 50%, P = 0.66, and 4-year OS 87% versus 77%, P = 0.17). PFS was superior for patients in the HDT/ASCR group compared with the RIT-CHOP group (65% versus 26% at 4 years, P < 0.01); there was no difference in the OS between treatment groups (84% at 4 years in both groups) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of prognostic factors in mantle cell lymphoma

| Treatment | % 4-Year PFS | Pa | % 4-Year OS | Pa |

| Type | <0.01 | 0.64 | ||

| Intensive (n = 69) | 65 | 84 | ||

| Conventional (n = 19) | 26 | 84 | ||

| MIPI | 0.83 | 0.13 | ||

| Low (n = 44) | 62 | 83 | ||

| Intermediate (n = 24) | 51 | 94 | ||

| High (n = 13) | 48 | 69 | ||

| sMIPI | 0.86 | 0.92 | ||

| Low (n = 42) | 63 | 82 | ||

| Intermediate (n = 28) | 54 | 92 | ||

| High (n = 11) | 43 | 75 | ||

| MIPI-Ki-67 | 0.87 | 0.13 | ||

| Low (n = 14) | 58 | 100 | ||

| Intermediate (n = 42) | 60 | 89 | ||

| High (n = 22) | 46 | 80 |

Log-rank test.

PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; MIPI, mantle cell international prognostic index; sMIPI, simplified MIPI.

proliferative index

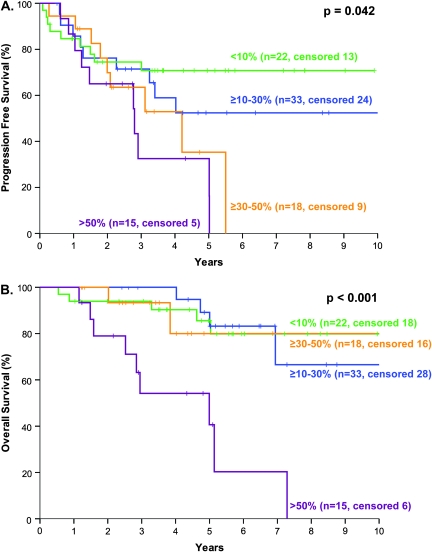

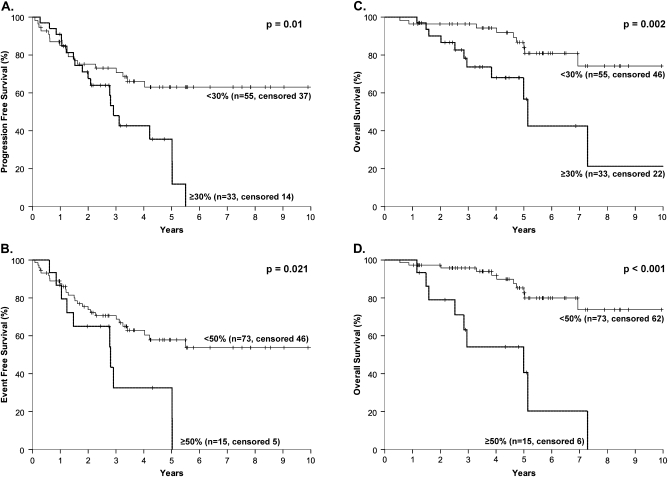

The distribution of patients according to PI subgroups is summarized in Table 1; survival is depicted in Figure 1. The patients were divided into four groups based on PI: 0–9.9, 10–29.9, 30–49.9, and >50%) (Figure 1A). However, as there was no difference in PFS or OS in patients with PI <10% and PI 10%–29.9%, the prognostic groups could be reduced to two based on the cut-off of 30% for PFS and 50% for OS (Figure 1B). A PI cut-off of 50% performed no better than a cut-off of 30% for PFS. Furthermore, the 30% cut-off split the sample into two subgroups of a reasonable number of patients (low PI, 53 patients; high PI, 33 patients) with prognostic relevance to both PFS and OS and was chosen as the cut-off for the multivariate analysis (Figure 2A and C). More importantly, there is a plateau in the PFS for patients with a PI <30% (Figure 2A). The results were similar when only the HDT/ASCR patients were analyzed (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) of patients with mantle cell lymphoma according to the proliferative index (Ki-67): <10% (blue); 10%–29.9% (green); 30%–49.9% (yellow); ≥50% (pink).

Figure 2.

Progression-free survival (A, B) and overall survival (C, D) according to the proliferative index (PI) higher or lower than 30% (A, C) or 50% (B, D) in 88 patients with mantle cell lymphoma.

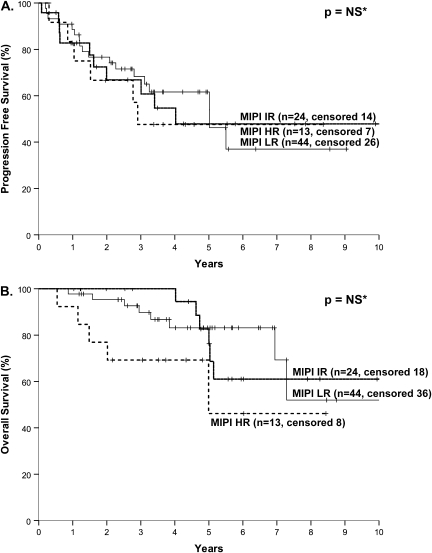

MIPI

The MIPI, sMIPI, and MIPI-Ki-67 failed to show prognostic significance for OS or PFS (Table 2, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) of patients with mantle cell lymphoma according to mantle cell international prognostic index score.

multivariate analysis

In the Cox regression analysis, the PI [hazard ratio (HR) 2.75, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.43–5.30)] and the treatment group (HR 4.52, 95% CI 2.32–8.80) retained their prognostic significance for PFS. We did not carry out multivariate analysis for OS because only PI showed prognostic importance in the univariate analysis.

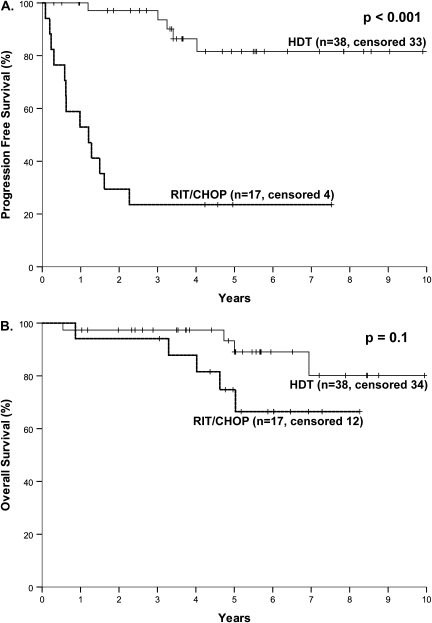

impact of treatment type according to PI

Among the low-PI patients, treatment type had a profound impact on PFS (P < 0.001) but not OS (P = 0.10) (Figure 4). At 5 years, 82% of patients who underwent HDT/ASCR remained free of progression as compared with 24% after RIT-CHOP. Furthermore, there were no relapses after 5 years among the patients who underwent HDT/ASCR (N = 15). There were not enough patients with high PI treated with RIT-CHOP to analyze the impact of treatment.

Figure 4.

Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) of patients with mantle cell lymphoma and a proliferative index <30% according to the planned therapy [high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem-cell rescue (HDT/ASCR) or radioimmunotherapy followed by combination chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (RIT-CHOP)].

discussion

Gene expression profiling has identified proliferation signature as a powerful predictor of outcome in MCL [22]. Several studies have shown that the PI estimated by percent of Ki-67-positive cells can be used to predict outcome [7, 10–18]. However, determination of PI by Ki-67 IHC is subject to interobserver variation limiting study-to-study comparison (R. Schaffel et al., unpublished data) [23]. Approaches have included manual counting and QIA. We applied QIA to Ki-67 determination in MCL and found it to be robust and reproducible (Schaffel et al., unpublished data) [10, 12, 15, 18].

In the current study, only PI determined by QIA was a prognostic factor for OS. Patients could be divided into two groups based on PI with the best cut-off value for PFS (30%) and for OS (50%). However, for practical purposes, a single cut-off was chosen for both PFS and OS using the 30% value. This generated two groups that retained prognostic significance for OS. Moreover, this cut-off has had prognostic importance in two other large studies [7, 10]. In multivariate analysis, the PI was strongly associated with PFS and was the only factor that predicted OS.

The possibility that a subgroup of patients with MCL could have a prolonged disease-free survival (DFS) was first described by Geisler et al. and has recently been confirmed [7, 24]. In our study, we corroborated this finding and showed that all patients who achieved long-term DFS (>5 years) had a PI of <30%. Moreover, this subset of patients could be found in both treatment programs, although the proportion was greater in the group consolidated with HDT/ASCR. The hypothesis that those patients may be cured is intriguing and requires longer follow-up.

Our study had some limitations. The relatively small number of patients precluded an independent determination of the PI cut-off. Rather, we sought to confirm cut-off values that had been previously reported. Furthermore, the sample size may have been too small to detect differences in outcome for PI cut-offs of <10% and 10%–29.9%. The subgroup of patients treated with RIT-CHOP included an insufficient number of patients with high-risk MIPI or high PI.

We also sought to determine whether the MIPI, sMIPI, or Ki-67-MIPI applied to our patient population. The MIPI and its variants were based on a population of 455 patients treated predominantly with CHOP ± R (87%), with only 80 patients (18%) treated with HDT/ASCR consolidation [19]. In that study, application of the MIPI to the subset of patients undergoing HDT/ASCR consolidation was not shown. Application of the sMIPI to 97 patients receiving intensive treatment with R-HyperCVAD/R-MA failed to demonstrate the ability of this model to predict outcome [20].

In the current study, we also could not confirm that MIPI and its variants predicted outcome. There are several possible explanations. First, the median follow-up is longer in the current study; the early separation in the curves disappears beyond 4.5 years (Figure 3B). Second, in the current study, median OS was longer than in the original dataset for the intermediate (not reached versus 51 months) and high-risk groups (not reached versus 29 months) [19]. This may be the consequence of more effective therapy available after first line than was available for patients in the original model. Thus, with the treatment regimens used in this study, we are unable to confirm the utility of the MIPI and its variants to predict outcome.

In conclusion, PI is the most important prognostic factor in MCL, and the 30% cut-off was confirmed in our study. In future clinical trials, 30% PI may be a useful parameter. QIA may help overcome the center-to-center variability in the determination of PI and increase general applicability.

funding

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center International Lymphoma Fellowship; postdoctoral program Coordenação de Aperfeicoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil (to R.S.); Lymphoma Research Fund (to A.D.Z.).

disclosure

None of the investigators in this study have a conflict of interest pertaining to the findings or outcomes of this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Carol Pearce for her excellent editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Zucca E, Roggero E, Pinotti G, et al. Patterns of survival in mantle cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1995;6:257–262. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a059155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen NS, Jensen MK, de Nully Brown P, Geisler CH. A Danish population-based analysis of 105 mantle cell lymphoma patients: incidences, clinical features, response, survival and prognostic factors. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:401–408. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrmann A, Hoster E, Zwingers T, et al. Improvement of overall survival in advanced stage mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:511–518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenz G, Dreyling M, Hoster E, et al. Immunochemotherapy with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone significantly improves response and time to treatment failure, but not long-term outcome in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1984–1992. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forstpointner R, Dreyling M, Repp R, et al. The addition of rituximab to a combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone (FCM) significantly increases the response rate and prolongs survival as compared with FCM alone in patients with relapsed and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2004;104:3064–3071. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romaguera JE, Fayad L, Rodriguez MA, et al. High rate of durable remissions after treatment of newly diagnosed aggressive mantle-cell lymphoma with rituximab plus hyper-CVAD alternating with rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7013–7023. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, et al. Long-term progression-free survival of mantle cell lymphoma after intensive front-line immunochemotherapy with in vivo-purged stem cell rescue: a nonrandomized phase 2 multicenter study by the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Blood. 2008;112:2687–2693. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fayad L, Thomas D, Romaguera J. Update of the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience with hyper-CVAD and rituximab for the treatment of mantle cell and Burkitt-type lymphomas. Clin Lymph Myeloma. 2007;8(Suppl 2):S57–S62. doi: 10.3816/clm.2007.s.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin P, Chadburn A, Christos P, et al. Outcome of deferred initial therapy in mantle-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1209–1213. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Determann O, Hoster E, Ott G, et al. Ki-67 predicts outcome in advanced-stage mantle cell lymphoma patients treated with anti-CD20 immunochemotherapy: results from randomized trials of the European MCL Network and the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2008;111:2385–2387. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raty R, Franssila K, Joensuu H, et al. Ki-67 expression level, histological subtype, and the International Prognostic Index as outcome predictors in mantle cell lymphoma. Eur J Haematol. 2002;69:11–20. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2002.01677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tiemann M, Schrader C, Klapper W, et al. Histopathology, cell proliferation indices and clinical outcome in 304 patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL): a clinicopathological study from the European MCL Network. Br J Haematol. 2005;131:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katzenberger T, Petzoldt C, Holler S, et al. The Ki67 proliferation index is a quantitative indicator of clinical risk in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2006;107:3407. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velders GA, Kluin-Nelemans JC, De Boer CJ, et al. Mantle-cell lymphoma: a population-based clinical study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1269–1274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.4.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schrader C, Janssen D, Klapper W, et al. Minichromosome maintenance protein 6, a proliferation marker superior to Ki-67 and independent predictor of survival in patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:939–945. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hui D, Reiman T, Hanson J, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of cdc2 is useful in predicting survival in patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1223–1231. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsi ED, Jung SH, Lai R, et al. Ki67 and PIM1 expression predict outcome in mantle cell lymphoma treated with high dose therapy, stem cell transplantation and rituximab: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B 59909 correlative science study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:2081–2090. doi: 10.1080/10428190802419640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia M, Romaguera JE, Inamdar KV, et al. Proliferation predicts failure-free survival in mantle cell lymphoma patients treated with rituximab plus hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone alternating with rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. Cancer. 2009;115:1041–1048. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoster E, Dreyling M, Klapper W, et al. A new prognostic index (MIPI) for patients with advanced-stage mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008;111:558–565. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah JJ, Fayad L, Romaguera J. Mantle Cell International Prognostic Index (MIPI) not prognostic after R-hyper-CVAD [author reply 2583–2584] Blood. 2008;112:2583. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zelenetz AD NA, Pandit-Taskar N, Scordo M, et al. Sequential radioimmunotherapy with tositumomab/iodine I131 tositumomab. followed by CHOP for mantle cell lymphoma demonstrates RIT can induce molecular remissions [abstract] In 42nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Edition Atlanta (USA): J Clin Oncol 2006; 24 (Suppl 18):(Abstr 7560) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenwald A, Wright G, Wiestner A, et al. The proliferation gene expression signature is a quantitative integrator of oncogenic events that predicts survival in mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:185–197. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Jong D, Xie W, Rosenwald A, et al. Immunohistochemical prognostic markers in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: validation of tissue microarray as a prerequisite for broad clinical applications (a study from the Lunenburg Lymphoma Biomarker Consortium) J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:128–138. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.057257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magni M, Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, et al. High-dose sequential chemotherapy and in vivo rituximab-purged stem cell autografting in mantle cell lymphoma: a 10-year update of the R-HDS regimen. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43:509–511. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]