Abstract

Machupo virus and Chapare virusare members of the Tacaribe serocomplex (virus family Arenaviridae) and etiological agents of hemorrhagic fever in humans in Bolivia. The nucleotide sequences of the complete Z genes, a large fragment of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase genes, the complete glycoprotein precursor genes, and the complete nucleocapsid protein genes of 8 strains of Machupo virus were determined to increase our knowledge of the genetic diversity among the Bolivian arenaviruses. The results of analyses of the predicted amino acid sequences of the glycoproteins of the Machupo virus strains and Chapare virus strain 200001071 indicated that immune plasma from hemorrhagic fever cases caused by Machupo virus may prove beneficial in the treatment of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever but not hemorrhagic fever caused by Chapare virus.

Keywords: Arenaviridae, Machupo virus, Bolivian hemorrhagic fever, Chapare virus, Latino virus

1. Introduction

The virus family Arenaviridae comprises Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), 4 other Old World species, 3 North American species, Tacaribe virus on Trinidad in the Caribbean Sea, and 13 South American species (Salvato et al., 2005). The South American species are Junín virus (JUNV) and Oliveros virus (OLVV) in Argentina, Machupo virus (MACV) and Latino virus (LATV) in Bolivia, Amapari virus (AMAV), Cupixi virus (CPXV), Flexal virus (FLEV), and Sabiá virus (SABV) in Brazil, Pichindé virus (PICV) in Colombia, Paraná virus (PARV) in Paraguay, Allpahuayo virus (ALLV) in Peru, and Guanarito virus (GTOV) and Pirital virus (PIRV) in Venezuela. Chapare virus (CHPV) is a provisional member of the Arenaviridae and known only from an outbreak of hemorrhagic fever that occurred in central Bolivia (Delgado et al., 2008).

Four South American arenaviruses in addition to CHPV naturally cause severe disease in humans: JUNV, MACV, SABV, and GTOV (Peters, 2002). These viruses are the etiological agents of Argentine hemorrhagic fever (AHF), Bolivian hemorrhagic fever (BHF), hemorrhagic fever in Brazil, and Venezuelan hemorrhagic fever (VHF), respectively.

Specific members of the rodent family Cricetidae, subfamily Sigmodontinae (Musser and Carleton, 2005) are the principal hosts of the South American arenaviruses for which natural host relationships have been well characterized. For example, the drylands vesper mouse (Calomys musculinus) in central Argentina is the principal host of JUNV (Mills et al., 1992) and the short-tailed cane mouse (Zygodontomys brevicauda) in western Venezuela is the principal host of GTOV (Fulhorst et al., 1999). Humans usually become infected with arenaviruses by direct or indirect contact with rodents or secretions or excretions from rodents.

Bolivian hemorrhagic fever was first recognized as a distinct clinical entity in 1959 near the town of San Joaquín in the Department of Beni in northeastern Bolivia (Mackenzie et al., 1964) (Fig. 1). Subsequently, an epidemic of BHF occurred in San Joaquín in the period from late 1962 or early 1963 through June 1964 (Mackenzie, 1965), sporadic cases and small outbreaks of BHF occurred in other communities in the Department of Beni (e.g., Kilgore et al., 1997; Stinebaugh et al., 1966; Villagra et al., 1994), and an outbreak of BHF occurred in a hospital in the Department of Cochabamba in central Bolivia. The results of an epidemiological investigation of the hospital outbreak (Peters et al., 1974) strongly suggested that the index case acquired her infection in the Department of Beni and that the MACV infections in the hospital personnel were a consequence of person-to-person virus transmission.

Fig. 1.

Map showing the 9 departments in Bolivia and the locations of (1) Guayaramerín, (2) Magdalena, (3) SanJoaquín, (4) Huacaraje, (5) SanRamón, (6) Chapare, (7) San Ignacio, and (8) Juan Latino. Strains of Machupo virus in this study were from hemorrhagic fever cases sampled from Guayaramerín, Huacaraje, Magdalena, San Joaquín, San Ramón, and Villamontes (location on the map not known) and from vesper mice (Calomys species) captured at sites near San Ramón. The Latino virus prototype strain MARU 10924 was isolated from a large vesper mice (C. callosus) captured near Juan Latino. Other strains of Latino virus were isolated in previous studies from sites near San Ignacio and sites in Brazil near southeastern Bolivia. The Chapare virus strain 200001071 was isolated from a person who lived and worked near the Chapare River in the Department of Cochabamba. The Departments of Beni and Santa Cruz and the northeastern region of the Department of Cochabamba are part of a vast plain that extends from the Andean foothills eastward to the Atlantic coast of central Argentina. The main economic activities in this region include agriculture, logging, and cattle ranching.

The MACV prototype strain Carvallo was isolated from a fatal BHF case that died in 1963 in San Joaquín (Johnson et al., 1965). Strains of MACV then were isolated from other BHF cases (e.g., Kilgore et al., 1997; Kuns, 1965; Peters et al., 1974; Villagra et al., 1994; Webb et al., 1967) and from vesper mice (a Calomys species other than Calomys callosus) captured in the Department of Beni (Johnson et al., 1966; Salazar-Bravo et al., 2002).

The CHPV prototype strain 200001071 was isolated from a person who succumbed to a febrile hemorrhagic illness in 2003 during an outbreak of hemorrhagic fever that occurred in the Department of Cochabamba (Delgado et al., 2008). This person had not traveled outside the Department of Cochabamba during the period before the onset of his illness. The identity of the principal host of CHPV has not yet been determined.

The LATV prototype strain MARU 10924 originally was isolated from a large vesper mouse (C. callosus) captured in 1965 near the town of Juan Latino in the Department of Santa Cruz in eastern Bolivia (Webb, 1984; Webb et al., 1973). Other strains of LATV were isolated from large vesper mice (C. callosus) captured near the town of San Ignacio in the Department of Santa Cruz and at localities in Brazil near southeastern Bolivia (Webb et al., 1973). There is no evidence that LATV is an agent of human disease.

The genomes of arenaviruses comprise 2 single-stranded RNA segments, designated large (L) and small (S) (Salvato et al, 2005). The L segment (~7.5 kb) consists of a 5′ non-coding region (NCR), the Z gene, an intergenic region that separates the Z gene from the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) gene, the RdRp gene, and a 3′ NCR. Similarly, the S segment (~3.5 kb) consists of a 5′ NCR, the glycoprotein precursor (GPC) gene, an intergenic region that separates the GPC gene from the nucleocapsid (N) protein gene, the N protein gene, and a 3′ NCR.

Our most comprehensive knowledge of the genetic diversity among strains of MACV previously was based on the sequences of a 634-nt fragment of the N protein genes of 28 strains: 22 from humans (BHF cases) and 6 from vesper mice (Table 1). The primary objective of this study was to increase our knowledge of the genetic diversity among strains of MACV and between MACV and the other Bolivian arenaviruses (i.e., CHPV and LATV). We expected that knowledge of the nucleotide sequences of the Z, RdRp, GPC, and complete N protein genes of multiple strains of MACV will prove useful in future work to develop rapid, accurate assays for MACV RNA in acute-phase biological specimens from febrile persons.

Table 1.

Machupo virus strains included in a neighbor-joining analysis of genetic distances generated from an alignment of nucleocapsid protein gene sequences, each sequence 634-nt in length.

| Straina | Isolated from | GenBank accession numbers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speciesb | Localityc | Yeard | ||

| Carvallo | Hsap | San Joaquín | 1963 | AY571954 |

| MARU 216606 | Hsap | San Joaquín | 1964 | AY571951 |

| MARU 217269 | Hsap | nk | 1964 | AY571952 |

| MARU 249121 | Hsap | nk | 1964 | AY571942 |

| MARU 223805 | Hsap | nk | 1965 | AY571953 |

| MARU 221600 | Csp | nk | 1965 | AY571949 |

| MARU 223455 | Csp | nk | 1965 | AY571948 |

| MARU 223671 | Csp | nk | 1965 | AY571956 |

| MARU 227774 | Hsap | nk | 1967 | AY571955 |

| MARU 228955 | Hsap | nk | 1967 | AY571950 |

| MARU 222688 | Hsap | nk | 1969 | AY571943 |

| MARU 250720 | Csp | nk | 1969 | AY571944 |

| MARU 258667 | Hsap | Villamontes | 1971 | AY571957 |

| Chicava | Hsap | San Ramón | 1993 | AY571947 |

| 9301012 | Csp | San Ramón | 1993 | AY571946 |

| 9301013 | Csp | San Ramón | 1993 | AY571945 |

| 9430069 | Hsap | Magdalena | 1994 | AY571936 |

| 9430071 | Hsap | Magdalena | 1994 | AY571937 |

| 9430072 | Hsap | Magdalena | 1994 | AY571932 |

| 9430075 | Hsap | Magdalena | 1994 | AY571933 |

| 9430076 | Hsap | Magdalena | 1994 | AY571938 |

| 9430078 | Hsap | Magdalena | 1994 | AY571934 |

| 9430081 | Hsap | Magdalena | 1994 | AY571939 |

| 9430082 | Hsap | Magdalena | 1994 | AY571935 |

| 9430084 | Hsap | Magdalena | 1994 | AY571940 |

| 9430666 | Hsap | Magdalena | 1994 | AY571941 |

| 9530537 | Hsap | Guayaramerín | 1995 | AY571958 |

| 200002427 | Hsap | Huacaraje | 2000 | AY571903 |

Strains 9430069 through 9430084 were from 4 members (A–D) of a family stricken by BHF in 1994: 9430072 from serum, 9430081 from liver, and 9430082 and 9430084 from blood of A, 9430078 from liver and 9430075 and 9430076 from serum of B, 9430069 from serum of C, and 9430071 from serum of D. Strain 9430666 was from a BHF case unrelated to the family stricken by BHF in 1994. Strain Chicava was from a person who worked at Estancia Balpebra (a ranch located approximately 43 km southwest of San Ramón), 9301012 was from a vesper mice captured on Estancia Balpebra, and 9301013 was from a vesper mouse captured near El Valle (a small community located approximately 41 km southwest of San Ramón and 2.5 km north of Estancia Balpebra).

Hsap, Homo sapiens (human); Csp, Calomys species (vesper mouse).

nk, not known but presumably located within the Department of Beni. All the other localities were located within the Department of Beni.

Year in which the sample was collected or year in which the rodent was captured.

There is no specific therapy for hemorrhagic fever caused by MACV or CHPV. However, immune plasma administered before the eighth day of clinical disease can markedly reduce the mortality of AHF (Enria and Maiztegui, 1994; Maiztegui et al., 1979; Ruggiero et al, 1986) and ribavirin (a ribonucleoside analogue) has shown promise in the treatment of AHF and febrile disease caused by SABV (Barry et al, 1995).

The benefit of passive antibody therapy for AHF has been positively associated with the capacity of immune plasma to neutralize the infectivity of JUNV in vitro (Enria et al., 1984). The results of a study done with murine monoclonal antibodies (Sanchez et al., 1989) indicated that neutralization of the infectivity of JUNV in vitro is exclusively associated with the viral glycoprotein(s), which are generated from the GPC by proteolytic cleavage within infected cells.

Several structural features of the GPC are conserved among the arenaviruses (Buchmeier, 2002). These features include a signal peptidase cleavage site after amino acid residue 58 (numbered from the initiating methionine) and a subtilase SKI-1/S1P cleavage site in the middle of the GPC. Co-translational cleavage of the GPC by a cellular signal peptidase yields the signal peptide (SP) and G1–G2 polypeptide; post-translational cleavage of the G1–G2 polypeptide by a cellular SKI-1/S1P protease yields the amino-terminal G1 and carboxy-terminal G2.

Previous studies established that antibody-mediated neutralization of infectivity in vitro can vary among strains of an arenavirus species (Jahrling and Peters, 1984; Parekh and Buchmeier, 1986), glycosylation and formation of intramolecular disulfide bonds during biosynthesis of the GPC can affect the capacity of monoclonal antibodies to neutralize the infectivity of LCMV (Wright et al., 1989), and the dominant neutralizing epitopes on an arenavirion are associated with G1 (Buchmeier et al, 1981). The secondary objective of this study was to examine the diversity of the primary structures of the MACV GPC and G1 as a prelude to the development of monoclonal antibodies for therapy of BHF.

2. Materials and methods

The analyses of the Z, RdRp, GPC, and N protein gene sequences in this study included MACV strains Carvallo, Chicava, Mallele (MARU 258667), 9301012, 9430084, 9530537, 200002427, MARU 216606, MARU 249121, and MARU 222688. Collectively, these 10 strains represent the 8 major phylogenetic lineages within MACV (Fig. 2) defined by an analysis of the nucleotide sequences of a 634-nt fragment of the N protein genes of the 28 MACV strains mentioned previously. Note that Mallele and MARU 258667 likely are synonymous since the laboratory records on strain MARU 258667 included the descriptor “L. Malale”, the sequence of the 634-nt fragment of the N protein gene of MARU 258667 (GenBank accession no. AY571957) is 100.0% identical to the nucleotide sequence of the homologous region of the N protein gene of MACV strain Mallele (AY619645), and the sequence of an 842-nt fragment of the GPC gene of MARU 258667 (AY571930) is 99.9% identical to the nucleotide sequence of the homologous region of the GPC gene of Mallele (AY619645).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationships among 28 strains of Machupo virus based on a neighbor-joining analysis of uncorrected p-model distances generated from an alignment of nucleocapsid protein gene sequences (Table 1), each sequence 634 nt. The lengths of the horizontal branches are proportional to nucleotide sequence divergence, the length of the scale bar is equivalent to a sequence divergence of 0.01, and the numerical values at the nodes indicate the percentage of 1000 bootstrap replicates that supported the interior branches. Bootstrap support values less than 70% are not listed. The Roman numerals indicate the 8 major phylogenetic lineages represented by the 28 strains.

The nucleotide sequences of a 324–373-nt fragment near the 5′ ends of the L segments of strains Chicava, 9301012, 9430084, 9530537, 200002427, MARU 216606, MARU 222688, and MARU 249121, and LATV strain MARU 10924, the nucleotide sequences of a 2153–2159-nt fragment near the 3' ends of the L segments of strains Chicava, 9301012, 9430084, 9530537, 200002427, MARU 216606, MARU 222688, and MARU 249121, and LATV strain MARU 10924, and the nucleotide sequences of a 3401-nt fragment of the S segments of strains Chicava, 9301012, 9430084, 200002427, MARU 216606, MARU 222688, and MARU 249121 were determined in this study. The fragment of the 5′ half of the L segment extended from within the 5′ NCR through the stop codon of the Z gene, the fragment of the 3′ half of the L segment extended from within the RdRp gene into the 3′ NCR, and the fragment of the S segment extended from within the 5′ NCR into the 3′ NCR. The nucleotide sequences of the L segments of strains Carvallo and Mallele, the nucleotide sequences of the S segments of strains Carvallo, 9530537, and MARU 10924, and the nucleotide sequences of the Z, RdRp, GPC, and N protein genes of the CHPV strain 200001071 and 13 other New World arenaviruses included in the analyses detailed below were acquired from the GenBank nucleotide sequence database (Table 2).

Table 2.

South American arenaviruses included in the analyses of small (S) genomic segment and large (L) genomic segment sequences.

| Speciesa | Strain | Hostb | Country | Yearc | GenBank accession number(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L segmentd | S segment | |||||

| ALLV | CLHP-2472 | Obic | Peru | 1997 | AY216502 | AY012687 |

| AMAV | BeAn 70563 | Ngui | Brazil | 1964 | AY924389 | AF512834 |

| CHPV | 200001071 | Hsap | Bolivia | 2003 | EU260464 | EU260463 |

| CPXV | BeAn 119303 | Ocap | Brazil | 1964 | AY216519 | AF512832 |

| FLEV | BeAn 293022 | Osp | Brazil | 1975 | EU627611 | AF512831 |

| GTOV | INH-95551 | Hsap | Venezuela | 1990 | AY358024 | AY129247 |

| JUNV | XJ13 | Hsap | Argentina | 1958 | AY358022 | AY358023 |

| JUNV | Romero | Hsap | Argentina | 1976 | AY619640 | AY619641 |

| LATV | MARU 10924 | Ccal | Bolivia | 1965 | AY960333e, AY935533e | AF512830 |

| MACV | Carvallo | Hsap | Bolivia | 1963 | AY358021 | AY129248 |

| MACV | Mallele | Hsap | Bolivia | 1971 | AY619644 | AY619645 |

| MACV | Chicava | Hsap | Bolivia | 1993 | AY960325e, AY935525e | AY924202e |

| MACV | MARU 216606 | Hsap | Bolivia | 1964 | AY960329e, AY935529e | AY924206e |

| MACV | MARU 222688 | Hsap | Bolivia | 1969 | AY960330e, AY935530e | AY924207e |

| MACV | MARU 249121 | Hsap | Bolivia | 1964 | AY960331e, AY935531e | AY924208e |

| MACV | 9301012 | Csp | Bolivia | 1993 | AY960328e, AY935528e | AY924205e |

| MACV | 9430084 | Hsap | Bolivia | 1994 | AY960326e, AY935526e | AY924203e |

| MACV | 9530537 | Hsap | Bolivia | 1995 | AY960332e, AY935532e | AY571959 |

| MACV | 200002427 | Hsap | Bolivia | 2000 | AY960327e, AY935527e | AY924204e |

| OLVV | 3229-1 | Bobs | Argentina | 1988 | AY211514 | U34248 |

| PARV | 12056 | Obuc | Paraguay | 1965 | EU627613 | AF485261 |

| PICV | An 3739 | Oalb | Colombia | 1965 | AF427517 | K02734 |

| PIRV | VAV-488 | Sals | Venezuela | 1994 | AY494081 | AF485262 |

| SABV | SPH 114202 | Hsap | Brazil | 1990 | AY358026 | U41071 |

| TCRV | TRVL 11573 | Asp | Trinidad | 1956 | J04340 | M20304 |

AMAV, Amapari virus; ALLV, Allpahuayo virus; CHPV, Chapare virus; CPXV, Cupixi virus; FLEV, Flexal virus; GTOV, Guanarito virus; JUNV, Junín virus; LATV, Latino virus; MACV, Machupo virus; OLVV, Oliveros virus; PARV, Paraná virus; PICV, Pichindé virus; PIRV, Pirital virus; SABV, Sabiá virus; TCRV, Tacaribe virus.

Asp, Artibeus species (frugivorous bat); Bobs, Bolomys obscurus (dark bolo mouse); Ccal, Calomys callosus (large vesper mouse); Csp, (Calomys species); Hsap, Homo sapiens (human); Ngui, Neacomys guianae (Guiana bristly mouse); Oalb, Oryzomys albigularis (Tomes’s oryzomys); Obic, Oecomys bicolor (bicolored arboreal rice rat); Obuc, Oryzomys buccinatus (Paraguayan oryzomys); Ocap, Oryzomys capito (large-headed oryzomys); Osp, Oryzomys species; Sals, Sigmodon alstoni (Alston’s cotton rat).

Year in which the specimen was collected.

A single accession number indicates that the sequence includes the entire Z gene and entire RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene; otherwise, the Z gene is included in the first accession and a 2142–2148-nt fragment of the RdRp gene is included in the second accession.

Sequence determined in this study.

2.1. Safety

All work with MACV was done inside a biosafety level 4 laboratory facility located on the Roybal Campus of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

2.2. Isolation of RNA and synthesis of first-strand cDNA

Monolayers of Vero E6 cells in 12.5 or 25.0 cm2 plastic flasks were inoculated with 0.2-mL of a 1:10 or 1:100 (v/v) dilution of stock virus and then maintained under a fluid overlay at 37 °C. Total RNA was isolated from adherent cells on the seventh or ninth day after inoculation, using TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) or TRI® Reagent (Sigma–Aldrich®, St. Louis, MO). The first-strand cDNA were synthesized as described previously (Cajimat and Fulhorst, 2004), using SuperScript II RNase H− Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Inc.) in conjunction with oligonucleotide 19C-cons (5′-CGCACMGWGGATCCTAGGC-3′). This oligonucleotide was expected to prime synthesis of first-strand cDNA from 4 different templates: the 3′ end of the L segment, the 3′ end of the L segment replicative intermediate, the 3′ end of the S segment, and the 3′ end of the S segment replicative intermediate (Cajimat and Fulhorst, 2004; Fulhorst et al., 2008).

2.3. Amplification of first-strand cDNA and sequencing reactions

The nucleotide sequences of the fragments near the 5′ and 3′ ends of each L segment were determined from PCR products. These amplicons were synthesized by using the MasterTaq® Kit (Eppendorf North America, Inc., Westbury, NY) and 19C-cons in conjunction with an oligonucleotide that annealed to the L segment first-strand cDNA downstream from the intergenic region and an oligonucleotide that annealed to the L segment first-strand cDNA upstream from the start codon of the RdRp gene, respectively.

The nucleotide sequence of each S segment was determined from 3 overlapping PCR products, designated “S1”, “S2”, and “S3”. S1 extended from within the 5′ NCR to a site upstream from the stop codon of the GPC gene, S2 extended from within the GPC gene to a site downstream from the stop codon of the N protein gene, and S3 extended from a site immediately downstream from the stop codon of the N protein gene, through the start codon of the N protein gene, and into the 3′ NCR. S1 and S3 were generated by using 19C-cons in combination with oligonucleotides that annealed to regions of the S segment near the stop codons of the GPC and N protein genes, respectively. S2 was generated by using an oligonucleotide that annealed to a region upstream from the stop codon of the GPC gene in combination with an oligonucleotide that annealed to a region downstream from the stop codon of the N protein gene.

All the PCR products for a particular virus were synthesized from a single first-strand cDNA reaction. Amplicons of the expected size were purified from agarose gel slices, using the QIAquick gel purification kit (Qiagen, Inc., Santa Clarita, CA). Both strands of each purified amplicon were sequenced directly, using the Applied Biosystems Prism sequencing kit (Foster City, CA).

The sequences of the oligonucleotides that were used to prime the PCR and sequencing reactions are available from M.N.B. Cajimat at nbcajirm@utmb.edu. The sequences of the fragment at the 5′ end of the L segments, the fragment at the 3′ end of the L segments, and the S segments were deposited into the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under accession nos. AY960325 through AY960333, AY935525 through AY935533, and AY924202 through AY924208, respectively (Table 2).

2.4. Data analysis

The Z, RdRp, GPC, and N protein gene sequences of the 10 MACV strains were compared to the homologous sequences of ALLV strain CLHP-2472, AMAV strain BeAn 70563, CHPV strain 200001071, CPXV strain BeAn 119303, FLEV strain BeAn 293022, GTOV strain INH-95551, JUNV strains XJ13 and Romero, LATV strain MARU 10924, OLVV strain 3229-1, PARV strain 12056, PICV strain An 3739, PIRV strain VAV-488, SABV strain SPH 114202, and TCRV strain TRVL 11573 (Table 2). The analyses of the nucleotide and amino acid sequences were done by using programs in the computer software package MEGA, version 4.0 (Tamura et al., 2007). The alignments of the predicted amino acid sequences were generated by using the program Clustal W1.7 (Thompson et al., 1994). The alignments of the nucleotide sequences were constructed based on the alignments of the predicted amino acid sequences. Nonidentities between sequences were equivalent to uncorrected p-model distances, with all 3 codon positions included in the calculation of the p-model distances. The nucleotide sequences of the L and S segments of LCMV strain WE (GenBank accession nos. AF004519 and M22138, respectively) were included in the neighbor-joining (NJ) analyses to enable inference of the ancestral node among the New World arenaviruses. Bootstrap support for the results of each NJ analysis was based on 1000 repetitions of the heuristic search, with random resampling of the data (Felsenstein, 1985). The hydropathy plots of the G1 of the 10 MACV strains and the G1 of CHPV strain 200001071 were generated using the Hopp–Woods scale and a window size of 7 residues (Hopp and Woods, 1983). The authors of this study expected that neutralizing epitopes would be clustered in hydrophilic region(s) with peak size >0.5.

3. Results

Nonidentities between the sequences of the Z, RdRp, GPC, and N protein genes of the 10 MACV strains ranged from 0.0 to 13.1%, 0.1 to 13.1%, 0.1 to 13.0%, and 0.2 to 12.0%, respectively. Nonidentities between the sequences of the Z, RdRp, GPC, and N protein genes of CHPV strain 200001071 and the sequences of the Z, RdRp, GPC, and N protein genes of the 10 MACV strains ranged from 37.0 to 39.5%, 39.4 to 40.5%, 40.3 to 41.5%, and 33.7 to 34.5%, respectively. Absolutely conserved sequences in the nucleotide sequence alignments restricted to CHPV and MACV were less than 12 nucleotides in length.

Nonidentities between the sequences of the Z, RdRp, GPC, and N protein genes of LATV strain MARU 10924 and the sequences of the Z, RdRp, GPC, and N protein genes of the 10 MACV strains ranged from 46.8 to 49.4%, 47.9 to 48.5%, 48.8 to 50.3%, and 36.9 to 38.2%, respectively, and nonidentities between the sequences of the Z, RdRp, GPC, and N protein genes of LATV strain MARU 10924 and the sequences of the Z, RdRp, GPC, and N protein genes of CHPV strain 200001071 were 43.4, 47.5, 45.1, and 38.4%, respectively. Absolutely conserved sequences in the nucleotide sequence alignments restricted to LATV and MACV were less than 8 nucleotides in length and absolutely conserved sequences in the nucleotide sequence alignments restricted to LATV and CHPV were less than 20 nucleotides in length.

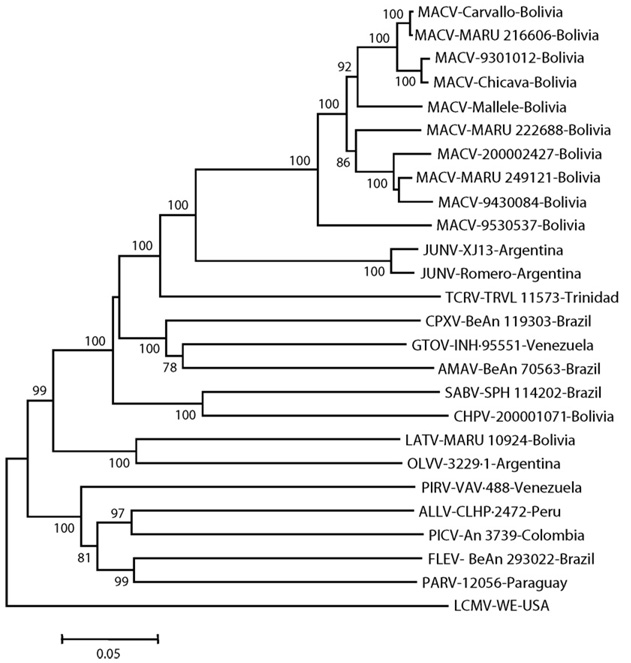

The results of the NJ analyses of the uncorrected genetic distances generated from the N protein gene sequence alignment indicated that the 10 MACV strains are monophyletic, MACV is phylogenetically most closely related to JUNV, CHPV is phylogenetically most closely related to SABV, and LATV is phylogenetically most closely related to OLVV (Fig. 3). Monophyly of (1) the 10 MACV strains, (2) MACV and JUNV, (3) CHPV and SABV, and (4) LATV and OLVV in the NJ analyses were strongly supported by the results of bootstrap analyses. The results of the NJ analyses of the uncorrected genetic distances generated from the Z, RdRp, and GPC gene sequence alignments (not shown) were essentially the same as the results of the NJ analyses of uncorrected genetic distances generated from the N protein gene sequence alignment (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic relationships among 10 strains of Machupo virus and 15 other New World arenaviruses based on a neighbor-joining analysis of uncorrected genetic (p-model) distances generated from an alignment of full-length nucleocapsid protein gene sequences. The lengths of the horizontal branches are proportional to nucleotide sequence divergence, the length of the scale bar is equivalent to a sequence divergence of 0.05, and the numerical values at the nodes indicate the percentage of 1000 bootstrap replicates that supported the interior branches. Bootstrap support values less than 70% are not listed. The branch labels include (in the following order) virus species, strain, and country of origin. The Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) strain WE is an Old World arenavirus and was included in the analysis to infer the ancestral node within the group of New World arenaviruses. ALLV, Allpahuayo virus; AMAV, Amapari virus; CHPV, Chapare virus; CPXV, Cupixi virus; FLEV, Flexal virus; GTOV, Guanarito virus; JUNV, Junín virus; LATV, Latino virus; MACV, Machupo virus; OLVV, Oliveros virus; PARV, Paraná virus; PICV, Pichindé virus; PIRV, Pirital virus; SABV, Sabiá virus; TCRV, Tacaribe virus.

The lengths of the GPC of the 25 New World viruses included in this study ranged from 479 to 518-aa (GTOV strain INH-95551 and OLVV strain 3229-1, respectively). The lengths of the GPC of the 10 MACV strains were identical (496-aa), 12-aa longer than the GPC of CHPV strain 200001071 (484-aa), and 19-aa shorter than the GPC of LATV strain MARU 10924 (515-aa).

The GPC of each MACV strain contained a potential signal peptidase cleavage site after residue 58 (SCS58↓) and a potential SKI-1/S1P cleavage site after residue 262 (RSLK262↓). Thus, the MACV G1 likely extends from residue 59 through residue 262. Similarly, the G1 of CHPV strain 200001071 likely extends from residue 59 (SCS58↓) through residue 250 (RRLQ250↓).

Identities between the amino acid sequences of the GPC and between the amino acid sequences of the G1 of the 10 MACV strains ranged from 94 to 100% and 89.2 to 100%, respectively. There was at least 1 non-conservative difference from the consensus of the 10 GPC sequences at 53 positions: 2 in the SP, 37 in G1, and 14 in G2. The GPC of all 10 MACV strains contained cysteine residues at 19 positions (57, 92, 135, 164, 207, 213, 220, 229, 237, 282, 295, 304, 313, 367, 388, 437, 466, 478, and 480) and potential N-glycosylation sites at 9 positions (83, 95, 137, 166, 178, 368, 376, 393, and 398).

Identities between the amino acid sequences of the GPC and G1 of CHPV strain 200001071 and the amino acid sequences of the GPC and G1 of the 10 MACV strains ranged from 55.4 to 56.4% and from 32.2 to 33.3%, respectively. The GPC of strain 200001071 contained cysteine residues at 16 positions (57, 85, 103, 129, 163, 225, 270, 283, 292, 301, 355, 376, 425, 454, 466, and 468) and potential N-glycosylation sites at 11 positions (69, 88, 99, 125, 171, 178, 218, 356, 364, 381, and 386).

The hydropathy plot of the G1 of MACV strain Carvallo (Fig. 4a) was visually indistinguishable from the hydropathy plots of the G1 of the 9 other MACV strains (not shown). Further, the correlation coefficients between the Hopp–Woods scores for the G1 of different MACV strains ranged from 0.937 (MARU 9301012 and 200002427) to 1.000 (Carvallo and MARU 216606, MARU 249121 and 9430084).

Fig. 4.

Hydropathy plots of the G1 glycoproteins of (a) Machupo virus strain Carvallo and (b) Chapare virus strain 200001071. The plots were generated using the Hopp–Woods scale and a window size of 7 residues.

Sites in the hydropathy plot of the G1 of MACV strain Carvallo (Fig. 4a) with peak size greater than 0.5 and sites in the hydropathy plots of the G1 of the 9 other MACV strains (not shown) with peak size greater than 0.5 were clustered in the region between residues 58 and 171 (residues numbered from the amino terminus of the G1). Nonidentities between the amino acid sequences of the 10 MACV strains in this 112-aa region ranged from 0.0 to 12.5%. There was at least 1 difference from the consensus of the 10 sequences at 23 positions between residues 58 and 171; however, the differences at only 8 of these positions were not conservative (Table 3).

Table 3.

Non-conservative differences between the predicted amino acid sequences of a 112-aa hydrophilic region in the G1 glycoproteins of 10 strains of Machupo virus.

| Amino acid residuea | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Sourceb | 61 | 75 | 92 | 102 | 112 | 127 | 148 | 154 |

| Carvallo | Hsap | M | G | N | P | K | A | P | V |

| Mallele | Hsap | M | G | N | S | M | A | S | L |

| Chicava | Hsap | M | G | N | P | K | V | P | K |

| MARU 216606 | Hsap | M | G | N | P | K | A | P | V |

| MARU 222688 | Hsap | M | G | N | P | K | V | P | V |

| MARU 249121 | Hsap | M | G | N | P | K | T | L | V |

| 9301012 | Csp | T | G | N | P | R | V | P | K |

| 9430084 | Hsap | M | G | N | P | K | T | L | V |

| 9530537 | Hsap | M | G | I | P | K | S | P | V |

| 200002427 | Hsap | S | E | N | P | V | T | L | V |

Positions of the residues are numbered from the amino-terminus of the G1. The blackened cells denote non-homologous differences from the consensus sequence.

Hsap, Homo sapiens; Csp, Calomys species.

The hydropathy plot of the G1 of CHPV strain 200001071 (Fig. 4b) contained a hydrophilic region between residues 1 and 151 (again, residues numbered from the amino terminus of the G1) and was very different from the hydropathy plot of the G1 of MACV strain Carvallo (Fig. 4a). Nonidentities between the amino acid sequences of this region of strain 200001071 and the amino acid sequences of the 112-aa hydrophilic region of the G1 of the 10 MACV strains ranged from 70.3 to 72.3%.

4. Discussion

The MACV strains from humans in this study represent a 38-year-period in the history of BHF. The results of a previous study indicated that the evolutionary histories of MACV strains Carvallo, Chicava, Mallele (MARU 258667), and MARU 249121 are independent of the evolutionary history of CHPV strain 200001071 (Delgado et al., 2008). The results of the NJ analyses of the Z, RdRp, GPC, and N protein gene sequence data in this study indicate that the evolutionary histories of MACV strains 9301012, 9430084, 9530537, 200002427, MARU 216606, and MARU 222688 also are independent of the evolutionary history of CHPV strain 200001071 and that the evolutionary history of the L segment of LATV is independent of the evolutionary histories of the L segments of MACV and CHPV.

The South American arenaviral hemorrhagic fevers are clinically similar to one another (Rollin et al., 2007). The onset of symptoms usually follows an incubation period of 1–2 weeks. The initial symptoms frequently include fever, malaise, myalgia and anorexia, followed by headache, back pain, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and severe prostration. Approximately one-third of untreated cases develop severe neurologic and/or hemorrhagic symptoms (e.g., tremors, delirium, convulsions, and coma, and petechiae, bleeding gums, and diffuse ecchymoses, respectively). Diagnosis of BHF during the acute phase of illness usually is based on the patient’s history, clinical symptoms, and – when available – the results of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) for arenavirus antigen and/or anti-arenavirus IgM in blood, plasma, or serum (Rollin et al., 2007).

A previous study demonstrated that the South American arenaviruses can be highly cross-reactive in ELISA (Fulhorst et al., 1997). Cross-reactivity between arenaviruses in ELISA and other antigen–antibody binding assays would be academic except that multiple arenaviruses are sympatric in some regions of South America (Fulhorst et al., 1997, 1999; Mills et al., 2007). As such, laboratory diagnosis of arenaviral infections based on detection of antigen or IgM could result in improper utilization of a virus-specific therapy (e.g., human immune plasma) in situations in which multiple pathogenic arenaviruses are sympatric.

The natural host relationships and geographical range of CHPV have not been rigorously investigated (Delgado et al., 2008). Hypothetically, the geographical range of CHPV includes the Department of Beni. If so, some “BHF” cases not included in this study could have been caused by CHPV, not MACV. Clearly, there is a need for rapid diagnostic assays that can differentiate BHF from hemorrhagic fever caused by CHPV in persons who live, work, or recently traveled in Bolivia east of the Andean Cordillera Oriental.

The nucleotide sequences of the MACV strains in this study together with the nucleotide sequences of CHPV strain 200001071 may prove useful in the development of accurate assays for MACV RNA and CHPV RNA in acute-phase clinical specimens from hemorrhagic fever cases. The development of these assays should include studies to determine whether assay sensitivity is dependent upon virus gene and disease severity as well as time elapsed since onset of infection.

Neutralization of the infectivity of an arenavirus in vitro usually is species-specific (e.g., Johnson et al., 1965; Wiebenga, 1965) and, as indicated previously, can vary from strain to strain within an arenavirus species (Jahrling and Peters, 1984; Parekh and Buchmeier, 1986). The results of this study indicate that the primary structures of the GPC and G1, including the number and locations of cysteine residues and potential N-linked glycosylation sites, are highly conserved among strains of MACV. Thus, immune plasma from some BHF cases likely will prove beneficial in the treatment of other BHF cases if administered soon after the onset of clinical symptoms. The results of this study also indicate that the primary structures of the GPC and G1 of CHPV strain 200001071 are markedly different from the primary structures of the GPC and G1 of MACV strain Carvallo, suggesting that immune plasma from BHF cases will not neutralize the infectivity of CHPV in vitro and, therefore, likely will not be beneficial in the treatment of hemorrhagic fever caused by CHPV. Note that studies to define the capacity of human immune plasma to neutralize the infectivity of the MACV strains in this study and CHPV strain 200001071 have not been done.

Rigorous evaluation of the effectiveness of immune plasma for therapy of BHF has been limited, in part, by the low number of qualified donors (Villagra et al., 1994). Monoclonal antibodies (including humanized murine monoclonal antibodies) may be safe, effective alternatives to immune plasma for therapy of BHF. Obviously, the initial phase in the development of monoclonal antibodies for therapy of BHF should include studies to assess the capacity of individual monoclonal antibodies to neutralize the infectivity of different strains of MACV and the potential for the emergence of neutralization escape mutants in vivo.

Acknowledgments

Mary Louise Milazzo and Maria N.B. Cajimat contributed equally to this study. Craig Manning (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Zoonotic, Viral, and Enteric Diseases) constructed the map in Fig. 1. Laura K. McMullan, Michelle Vanoy, and Heather L. Wurtzel (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Infectious Diseases) determined the nucleocapsid protein gene sequences listed in Table 1. Natalie A. Dodsley-Prow (The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston) assisted with the characterization of the small genomic segments of MACV strains Chicava, MARU 216606, MARU 222688, MARU 249121, 9301012, 9430084, and 200002427. National Institutes of Health grant AI-53428 (“Rapid, accurate diagnostic assays for arenaviral infections”) provided financial support for this study. A Presidential Leave Award from John D. Stobo (President, The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston) provided salary for Charles F. Fulhorst while he worked on this study at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, GA.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this study do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agencies.

References

- Barry M, Russi M, Armstrong L, Geller D, Tesh R, Dembry L, Gonzalez JP, Khan AS, Peters CJ. Brief report: treatment of alaboratory-acquired Sabiá virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:317–318. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508033330505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmeier MJ. Arenaviruses: protein structure and function. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002;262:159–173. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56029-3_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmeier MJ, Lewicki HA, Tomori O, Oldstone MBA. Monoclonal antibodies to lymphocytic choriomeningitis and Pichinde viruses: generation, characterization, and cross-reactivity with other arenaviruses. Virology. 1981;113:73–85. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajimat MNB, Fulhorst CF. Phylogenyof the Venezuelan arenaviruses. Virus Res. 2004;102:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado S, Erickson BR, Agudo R, Blair PJ, Vallejo E, Albariño CG, Vargas J, Comer JA, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Olson JG, Nichol ST. Chapare virus, a newly discovered arenavirus isolated from a fatal hemorrhagic fever case in Bolivia. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000047. (e1000047) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enria D, Maiztegui JI. Antiviral treatment of Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Antivir. Res. 1994;23:23–31. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enria DA, Briggiler AM, Fernandez NJ, Levis SC, Maiztegui JI. Importance of dose of neutralizing antibodies in treatment of Argentine haemorrhagic fever with immune plasma. Lancet. 1984;2:255–256. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulhorst CF, Bowen MD, Salas RA, de Manzione NM, Duno G, Utrera A, Ksiazek TG, Peters CJ, Nichol ST, de Miller E, Tovar D, Ramos B, Vasquez C, Tesh RB. Isolation and characterization of Pirital virus, a newly discovered South American arenavirus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1997;56:548–553. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulhorst CF, Bowen MD, Salas RA, Duno G, Utrera A, Ksiazek TG, de Manzione NMC, de Miller E, Vasquez C, Peters CJ, Tesh RB. Natural rodent host associations of Guanarito and Pirital viruses (family Arenaviridae) in central Venezuela. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1999;61:325–330. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulhorst CF, Cajimat MNB, Milazzo ML, Paredes H, de Manzione NMC, Salas RA, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG. Genetic diversity between and within the arenavirus species indigenous to western Venezuela. Virology. 2008;378:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopp TP, Woods KR. A computer program for predicting protein antigenic determinants. Mol. Immunol. 1983;20:483–489. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(83)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahrling PB, Peters CJ. Passive antibody therapy of Lassa fever in cynomologus monkeys: importance of neutralizing antibody and Lassa virus strain. Infect. Immun. 1984;44:528–533. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.2.528-533.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KM, Wiebenga NH, Mackenzie RB, Kuns ML, Tauraso NM, Shelokov A, Webb PA, Justines G, Beye HK. Virus isolations from human cases of hemorrhagic fever in Bolivia. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1965;118:113–118. doi: 10.3181/00379727-118-29772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KM, Kuns ML, Mackenzie RB, Webb PA, Yunker CE. Isolation of Machupo virus from wild rodent Calomys callosus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1966;15:103–106. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1966.15.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilgore PE, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Mills JN, Villagra MR, Montenegro MJ, Costales MA, Paredes LC, Peters CJ. Treatment of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever with intravenous ribavirin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1997;24:718–722. doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuns ML. Epidemiology of Machupo virus infection. II. Ecological and control studies of hemorrhagic fever. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1965;14:813–816. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1965.14.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie RB. Epidemiology of Machupo virus infection. I. Pattern of human infection, San Joaquín, Bolivia, 1962–1964. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1965;14:808–813. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1965.14.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie RB, Beye HK, Valverde L, Garrón H. Epidemic hemorrhagic fever in Bolivia. I. A preliminary report of the epidemiologic and clinical findings in a new epidemic area in South America. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1964;13:620–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiztegui JI, Férnandez NJ, de Damilano AJ. Efficacy of immune plasma in treatment of Argentine haemorrhagic fever and association between treatment and a late neurological syndrome. Lancet. 1979;2:1216–1217. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JN, Ellis BA, McKee KT, Jr, Calderon GE, Maiztegui JI, Nelson GO, Ksiazek TG, Peters CJ, Childs JE. A longitudinal study of Junin virus activity in the rodent reservoir of Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1992;47:749–763. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JN, Alva H, Ellis BA, Wagoner KD, Childs JE, Calderón G, Enría DA, Jahrling PB. Dynamics of Oliveros virus infection in rodents in central Argentina. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:315–323. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2006.0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musser GG, Carleton MD. Superfamily Muroidea. In: Wilson DE, Reeder DM, editors. Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. pp. 894–1522. [Google Scholar]

- Parekh BS, Buchmeier MJ. Proteins of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, antigenic topography of the viral glycoproteins. Virology. 1986;153:168–178. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters CJ. Human infection with arenaviruses in the Americas. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002;262:65–74. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56029-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters CJ, Kuehne RW, Mercado RR, Le Bow RH, Spertzel RO, Webb PA. Hemorrhagic fever in Cochabamba, Bolivia, 1971. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1974;99:425–433. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollin PE, Nichol ST, Zaki S, Ksiazek TG. Arenaviruses and filoviruses. In: Murray PR, Baron EJ, Landry ML, Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA, editors. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 9th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology Press; 2007. pp. 1510–1522. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero HA, Perez Isquierdo F, Milani HA, Barri A, Val A, Maglio F, Astarloa L, Gonzalez Cambaceres C, Milani HL, Tallone JC. Treatment of Argentine hemorrhagic fever with convalescent’s plasma, 4433 cases. Presse Med. 1986;15:2239–2242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Bravo J, Dragoo JW, Bowen MD, Peters CJ, Ksiazek TG, Yates TL. Natural nidality in Bolivian hemorrhagic fever and the systematics of the reservoir species. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2002;1:191–199. doi: 10.1016/s1567-1348(02)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvato MS, Clegg JCS, Buchmeier MJ, Charrel RN, Gonzalez JP, Lukashevich IS, Peters CJ, Rico-Hesse R, Romanowski V. Family Arenaviridae. In: Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA, editors. Virus Taxonomy: Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier Academic Press; 2005. pp. 725–733. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez A, Pifat DY, Kenyon RH, Peters CJ, McCormick JB, Kiley MP. Junin virus monoclonal antibodies: characterization and cross-reactivity with other arenaviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 1989;70:1125–1132. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-5-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinebaugh BJ, Schloeder FX, Johnson KM, Mackenzie RB, Entwisle G, de Alba E. Bolivian hemorrhagic fever. A report of four cases. Am. J. Med. 1966;40:217–230. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(66)90103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W (1.7): improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choices. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villagra M, Suarez L, Arce R, Moreira MG. Bolivian hemorrhagic fever—El Beni Department, Bolivia, 1994. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 1994;43:943–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb PA. Latino virus. In: Berge TO, editor. International Catalogue of Arboviruses; Including Certain Other Viruses of Vertebrates. American Committee on Arthropod-borne Viruses. Subcommittee on Information Exchange, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.), and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (U.S.); 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Webb PA, Johnson KM, Mackenzie RB, Kuns ML. Some characteristics of Machupo virus, causative agent of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1967;16:531–538. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1967.16.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb PA, Johnson KM, Peters CJ, Justines G. Behavior of Machupo and Latino viruses in Calomys callosus from two geographic areas of Bolivia. In: Lehmann-Grube F, editor. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis Virus and Other Arenaviruses. Berlin, Heidelberg & New York: Springer; 1973. pp. 313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Wiebenga NH. Immunologic studies of Tacaribe, Junín and Machupo viruses. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1965;14:802–808. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1965.14.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KE, Salvato MS, Buchmeier MJ. Neutralizing epitopes of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus are conformational and require both glycosylation and disulfide bonds for expression. Virology. 1989;171:417–426. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]