Abstract

We investigated the role of parents’ and children’s religiosity in behavioral adjustment among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Data were collected on 170 maltreated and 159 nonmaltreated children from low-income families (mean age = 10 years). We performed dyadic data analyses to examine unique contributions of parents’ and children’s religiosity and their interaction to predicting child internalizing and externalizing symptomatology. A four group structural equation modeling was used to test whether the structural relations among religiosity predictors and child outcomes differed by child maltreatment status and child gender. We found evidence of parent-child religiosity interaction suggesting that (1) parents’ frequent church attendance was related to lower levels of internalizing symptomatology among nonmaltreated children with low church attendance and (2) parents’ importance of faith was associated with lower levels of internalizing and externalizing symptomatology among nonmaltreated children with low faith. The results suggest that independent effects of parents’ religiosity varied depending on children’s religiosity and parent-child relationship.

Keywords: Child Maltreatment, Religiosity, Interdependence, Internalizing Symptomatology, Externalizing Symptomatology

Introduction

The existing literature on the role of religiosity in youth development is in general consensus that child/adolescent religiosity promotes positive development and offers protection against risk behaviors and mental health problems. Past research has identified religiosity as having a protective effect against conduct problems, delinquency (Lerner & Galambos, 1998; Marsiglia, Kulis, Niery, & Parsai, 2005; Pearce, Jones, Schwab-Stone, & Ruchkin, 2003), and depression (Pearce, Little, & Perez, 2003; Schapman, & Inderbitzen-Nolan, 2002; Wright, Frost, & Wisecarver, 1993) among children and adolescents. In studying the role of religiosity among children, parents’ religiosity deserves attention because of its relation to both children’s religiosity and adjustment. Parents can have considerable influence over their children’s beliefs and behaviors, including religiosity in childhood and adolescence. Yet, no systematic study has been conducted with regard to the role of parents’ religiosity in behavioral adjustment among maltreated children. The current study examines the contributions of both parents’ and children’s religiosity and the interaction effects between parents’ and children’s religiosity to behavioral adjustment among high-risk children with and without maltreatment experiences.

Religiosity seems to be a protective mechanism against the detrimental effects of risk factors, including familial adversity and stressful life events. The notion of personal religion or faith as a resilience factor appears in the early work of resilience research. In a longitudinal study of resilience, Werner and Smith (1982) followed a group of high-risk children who were born into poor and troubled families into adulthood. For those resilient individuals who fared well academically and interpersonally by age 18, spirituality/religiosity was identified among the most important protective factors associated with resilience. This finding implies that religiosity may be a moderating factor (i.e., a resilience factor) in the link between earlier negative life events and later developmental outcomes. Similarly, other researchers have revealed that religious beliefs and church attendance form an important coping mechanism for negotiating life stresses. For example, adolescents who lived in high-poverty areas were more likely to stay on track academically if they were high in church attendance compared to those who were low in church attendance (Regnerus & Elder, 2003). Another study reports that religiosity may be a resilience factor that accounts for why some teen mothers and their children, who are at increased risk for negative developmental outcomes, fare better than others. In a sample of adolescent mothers and their children, mothers with greater religiosity (defined as church involvement and dependence on church officials and members) had higher educational attainment, higher self-esteem, and lower depression scores than mothers with lower religiosity (Carothers, Borkowski, Lefever, & Whitman, 2005).

Child maltreatment represents one of the most profound risk factors that disrupt the course of normal development. Victims of child maltreatment typically evidence difficulties in multiple domains of development including physical, psychological, cognitive, and behavioral development (Cicchetti & Toth, 2005). Empirical findings have documented that maltreated children show higher levels of both internalizing symptomatology (Bolger & Patterson, 2001; Keiley, Howe, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 2001; Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2001) and externalizing symptomatology (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2001; Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1997; Manly et al., 2001) compared to nonmaltreated children from a similar socio-economic background.

The role of religiosity relating to childhood maltreatment experiences is rather complex. In a recent study of religiosity among maltreated and nonmaltreated children, the protective roles of children’s religiosity varied by risk status and gender (Kim, 2008). More specifically, child reports of the importance of faith were related to lower levels of internalizing symptomatology among maltreated girls. This finding supports the buffering effects model by showing that the link between children’s religiosity and internalizing symptomatology was stronger among maltreated girls compared to nonmaltreated girls. In contrast, children’s church attendance was associated with lower levels of externalizing symptomatology for nonmaltreated boys, but not for maltreated boys. It appears that church attendance was not a strong enough protective factor for attenuating the effects of maltreatment on externalizing behaviors among boys. This finding is consistent with the contention that when risk factors outweigh the benefits of the protective factors, children’s adjustment will deteriorate despite the presence of those protective factors (Zielinski & Bradshaw, 2006).

In contrast to the role of children’s own religiosity, little is known regarding the mechanisms that underlie the influence of parents’ religiosity in child development. However, social control theory (Hirschi & Stark, 1969; Smith, 2003) offers an insightful explanation regarding the buffering effects of parents’ religiosity on maladjustment of their children. Social control theory characterizes religious communities as social networks of relational ties that (1) facilitate more informed and effective oversight and control of children by adults who care about them, and (2) model prosocial behavior while reinforcing parental values and controls. Religious parents are more likely to be involved in such relational networks that facilitate oversight of child behavior as well as the child’s internalization of adult norms regarding appropriate behavior (e.g., Bartkowski, Xu, & Levin, 2008).

Indeed, prior studies demonstrate positive effects of parents’ religiosity on child adjustment. A study by Caputo (2004) using a national sample of adolescents demonstrated that parents’ religiosity (measured by their feelings about religion and religious practices) was positively associated with good physical health and inversely related to substance abuse. In a recent study using a national sample of early elementary school age children, Bartkowski and colleagues (2008) reported that higher frequencies of mothers’ and fathers’ church attendance were related to lower levels of internalizing and externalizing symptomatology of their children as reported by teachers. Parents’ religiosity seems to work together with parents’ warm and supportive behaviors and effective monitoring to result in positive behavioral and emotional outcomes among children and adolescents (Bartkowski & Wilcox, 2000; Gunnoe, Hetherington, & Reiss, 1999; Pearce & Axinn, 1998; Wilcox, 1998, 2002). Brody, Stoneman and Flor (1996) showed that parents’ religiosity (measured by the frequency and the importance of church attendance) was related to positive parenting practices, which in turn were positively associated with cognitive and social competence and negatively associated with internalizing symptomatology among African American children.

The impact of parents’ religiosity may depend on child gender. Regnerus (2003a) investigated both parents’ and children’s religiosity and reported an interesting gender difference showing that parents’ religious devotion protected girls better than boys. More specifically, both parents’ religiosity and children’s religiosity were negatively related to delinquent behaviors among girls. For boys, however, greater parents’ religiosity was related to higher delinquency, and their own religiosity was not related to delinquency. Such a finding indicates that parents’ religiosity may not provide a uniformly protective influence on their children, but the effects of parents’ religiosity on child outcomes may depend on some other contextual factors including child gender.

There is evidence that congruence in religiosity between parents and children is important. Pearce and Axinn (1998) found that mother-child dyads characterized by high congruence in religiosity showed a more positive mother-child relationship. In addition, adolescents who disagreed with their parents about the importance of religion showed greater delinquency than adolescents who agreed with their parents that religion was very important (Pearce & Haynie, 2004). Prior studies also suggest that intergenerational transmission of religiosity differs depending on child gender and parent-child relationship quality. Boys’ religious behaviors are more affected by parental religious modeling than girls’ (Flor & Knapp, 2001). Religious socialization is more likely to occur in families characterized by considerable warmth and closeness (Myers, 1996; Ozorak, 1989), and parents’ religiosity is more likely to be transmitted to children when there are high levels of parental acceptance and more secure attachment between parent (especially mother) and offspring (Bao, Whitbeck, Hoyt, & Conger, 1999; Granqvist, 2002; Weigert & Thomas, 1972). Given that the parenting practices of adults who maltreat their children tend to be more authoritarian (i.e., less accepting and more punitive) than those of parents who are nonmaltreaters (Baumrind, 1995), it is expected that congruence between parents’ and children’s religiosity will be weaker in maltreating families than nonmaltreating families.

One critical issue in studying children’s religiosity is to examine the interdependence between parents’ and children’s religiosity on child outcomes. There exists a notable resemblance between parent and offspring religiosity in childhood and adolescence, with a correlation typically greater than .50 (e.g., Flor & Knapp, 2001). In addition, behavior genetics studies indicate that heritability of adolescent religiosity due to genetic factors is weak and that variances in religiosity are explained mostly by family environment factors (most often indicated by parenting behaviors) (D’Onofrio, Eaves, Murrelle, Maes & Spilka, 1999; Koenig, McGue, Krueger, & Bouchard, 2005). Collectively, the findings imply that family resemblance comes from the fact that children adopt their parents’ levels of religiosity and further points out the need for considering parent religiosity in drawing conclusions about the role of child/adolescent religiosity.

To our knowledge, no systematic investigation has been performed on parents’ and children’s religiosity simultaneously relating to behavioral adjustment among maltreated children. In the present study, we performed dyadic data analyses to examine unique contributions of parents’ religiosity, above and beyond the contribution of children’s own religiosity, and the interaction between parents’ and children’s religiosity to predicting child adjustment outcomes. Specifically, if parents’ religiosity had buffering effects, then the protective effects of parents’ religiosity on child behavioral adjustment will be stronger among maltreated children than nonmaltreated children. Alternatively, if the impact of parents’ religiosity is attenuated by negative parenting behaviors that are associated with child maltreatment, then parents’ religiosity will have stronger effects on child outcomes among nonmaltreated children than maltreated children. Furthermore, we investigated whether the impact of parents’ religiosity may vary depending on the level of children’s religiosity. Finally, we examined whether the associations between parents’ and children’s religiosity predictors and child adjustment outcomes may differ between maltreating and nonmaltreating families and between boys and girls.

Methods

Participants

Participants in the present study consisted of 170 maltreated children (99 boys and 71 girls) and 159 nonmaltreated children (69 boys and 90 girls) who attended a summer day camp research program in a Northeastern urban city and their primary caregivers (88% mothers, 4% fathers, 5% grandmothers, 3% others). The summer camp program was designed to provide maltreated and nonmaltreated children from economically disadvantaged families with a naturalistic setting in which children’s behavior and peer interactions could be observed in an ecologically valid context. Children were between the ages of 6 and 12 years (M = 10.19 years, SD = 1.81). The sample consisted of children from diverse ethnic backgrounds: 64% African American, 17% European American, 16% Hispanic American, and 3% other ethnic groups.

Table 1 presents demographic information for the maltreating and nonmaltreating comparison families. The maltreated group and the nonmaltreated group were comparable with respect to demographic features including child age, child ethnicity (White vs. non-White), family reliance on welfare (receiving full or partial Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or TANF), and parental marital status (being headed by single parents, almost all families were headed by mothers). There were more boys in the maltreated group compared to the nonmaltreated group, consistent with gender ratios in the maltreated population. More families in the maltreated group belonged to the lower socioeconomic status compared to the families in the nonmaltreated group (the two lowest socioeconomic strata defined by Hollingshead, 1975). In addition, there were significant differences between the maltreated group and the nonmaltreated group in regard to parental ethnicity (White vs. non-White) and parental education levels (having less than or equal to a high school diploma). Parent and child demographic variables (child age, child gender, child ethnicity, parent age, parent gender, parent ethnicity, and parent education) were not significantly related to child outcome variables (internalizing and externalizing symptomatology), with the only exception being a moderate yet significant correlation between child ethnicity and externalizing symptomatology. Ethnic minority children showed greater externalizing symptomatology than ethnic non-minority children (r = .12, p < .05). Because the demographic variables, in general, were not significantly correlated with the dependent variables (child outcomes), they were not included in the main analyses.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics for maltreatment and nonmaltreatment groups

|

M (SD) or percentage |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Nonmaltreated (n = 159) | Maltreated (n = 170) | t or χ2 |

| Child age (years) | 10.11 (1.76) | 10.26 (1.86) | .74 |

| Child gender (% male) | 43% | 58% | 7.24* |

| Child ethnicity (% non-White) | 86% | 80% | 2.21 |

| Parent ethnicity (% non-White) | 86% | 68% | 14.53* |

| Parent education (% ≤ High school) | 54% | 67% | 5.80* |

| Family Hollingsheada (% below level 2) | 71% | 84% | 10.49* |

| Receiving public assistancea | 79% | 83% | 1.18 |

| Marital status (% not married) | 65% | 61% | .48 |

Because of missing data, analyses of family Hollingshead involved a total of 324 children, and analyses of receiving public assistance involved a total of 327 children.

p < .05.

Procedure

Maltreated children had been identified through the Department of Human and Health Services (DHHS) as having experienced child maltreatment. A staff member from the DHHS assisted in obtaining parental consent for examination of the DHHS records. All existing DHHS records were coded by raters utilizing a standardized classification system for child maltreatment developed by Barnett, Manly, and Cicchetti (1993). Because most families in which maltreatment reports occurred were of lower socioeconomic status and had high rates of poverty, the nonmaltreated low-income comparison group was recruited from families receiving Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF). These families were selected based on their similarity to the demographic characteristics of the maltreating families. Prior to recruitment, the DHHS staff member screened those potential families for any history of child maltreatment based on searches of the Child Protective Services (CPS) maltreatment registry. Screened TANF families with children in the target age range were randomly selected and approached for enrollment in the same way as the maltreating families. Parental consent was obtained from targeted families to review the DHHS records to confirm the absence of any documented maltreatment in these families. If any reports of child maltreatment or any ambiguous child maltreatment information were discovered for a family, the child was not included in the study.

Possibly eligible families were administered screening interviews by telephone or in their homes to inform them about the study procedures and camp program, and to obtain written informed consent and demographic information from the primary caregivers. About 90 % of families who were approached agreed to have their children participate in the summer camp program. In camp, children participated in a variety of recreational activities that were appropriate to their developmental level and interests in groups of six to eight same-age and same-sex peers. In addition, the children took part in a variety of research assessments. Every week, six groups of children participated in the camp and each camp group was led by three trained camp counselors. Half of the children in each of the groups were maltreated and the other half were nonmaltreated. Camp lasted for 5 days, 7 hours per day, providing a total of 35 hours of interaction between children and counselors (see Cicchetti & Manly, 1990, for detailed descriptions of camp procedures). The counselors, who were unaware of the children’s maltreatment status and of the research hypotheses, completed a number of assessment instruments at the end of each week. Primary caregivers were interviewed and administered study measures during home visits that were completed within about one month of their child’s camp attendance.

Measures

Child Maltreatment

The narrative reports of the maltreatment incidents from the DHHS records were coded according to the Maltreatment Classification System (MCS, Barnett et al., 1993). The MCS provided operational definitions and specific criteria for rating the severity of multiple subtypes of maltreatment (See Barnett et al. 1993, for a detailed description of the nosological system used to code incidents for maltreatment). Severity of each subtype was rated along a 5-point scale, with 1 indicating mild maltreatment to 5 indicating severe maltreatment of the specified subtype. Additionally, the MCS coding involved measurement of onset and frequency of each subtype, perpetrator(s) within each subtype, and the developmental period(s) during which each subtype occurred.

Among maltreated children, 62% had been emotionally maltreated, 78% had been neglected, 27% had been physically abused, and 6% had been sexually abused. Consistent with the high co-occurrence of subtypes that are found in the literature (cf. Manly et al., 2001), 58% of the maltreated children in this sample experienced two or more forms of maltreatment. The majority of maltreated children (95%) had their parents as perpetrators for some form of maltreatment. More specifically, 88% of the maltreated children had mothers as perpetrators, 40% had fathers as perpetrators and 37% had others (e.g., relatives) as perpetrators. For each subtype, weighted kappa statistics were calculated to account for reliability. Interrater agreement was good, with kappas of 1.0 for sexual abuse, .94 for physical abuse, .78 for emotional maltreatment, and a range of .79–.85 for physical neglect.

Religiosity

The religiosity measure used for both parents and children consisted of 2 items adapted and revised from the National Survey of Children (NSC; e.g., Gunnoe & Moore, 2002). The first item assessed organizational religiosity by asking frequency of attendance at religious services and activities: Responses ranged from 1 (Two or three times a week) to 5 (Never). The second item assessed personal religiosity by asking the importance of religious faith with responses ranging from 1 (Very important) to 5 (Not at all important). These two items were reverse coded so that higher scores reflected greater religiosity.

Children’s behavior problems

Children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors were rated by camp counselors using the Teacher’s Report Form of the Child Behavior Checklist (TRF, Achenbach, 1991). The TRF is a widely used and well-validated instrument to assess a wide range of child behavioral disturbance. It consists of 118 items about behavioral problems rated for frequency of occurrence, including two broadband dimensions of child symptomatology – externalizing behavior problems (e.g., aggressive behaviors, delinquent behaviors) and internalizing behavior problems (e.g., withdrawal, somatic complaints, anxiety-depression). Two counselors’ scores (T scores) for each child were averaged to obtain individual child scores for externalizing and internalizing symptomatology. Inter-rater reliabilities (intraclass correlations) were from .84 for externalizing symptomatology and .78 for internalizing symptomatology.

Data analysis strategy

The present investigation used a series of t-tests to examine the differences in parents’ and children’s religiosity and behavioral adjustment outcomes between the maltreated and the nonmaltreated groups. Given the high overlap in the multiple maltreatment subtypes, maltreated and nonmaltreated groups, rather than distinct subtypes, were compared. We examined relative contributions of parents’ religiosity and children’s own religiosity to predicting child behavioral adjustment by using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). It was crucial to consider nonindependence between parents’ and children’s religiosity scores, because two scores from the two members of parent-child dyad might be more similar to each other than were two scores from two people who were not members of the same dyad. The interdependence between parents’ and children’s religiosity was estimated by the interaction between parents’ and children’s religiosity. We performed a four group structural equation model (SEM) to test whether the contributions of parents’ and children’s religiosity and their interaction to child outcomes differed by child maltreatment status and child gender.

Results

Table 2 shows means and standard deviations for study variables. Maltreated children, compared to nonmaltreated children, exhibited significantly higher levels of externalizing symptomatology, t (327) = 2.08, p < .05, and higher levels of internalizing symptomatology with a marginal significance, t (327) = 1.80, p = .07. With respect to religiosity, nonmaltreated children were higher in reporting the importance of faith than maltreated children, t (327) = 1.93, p = .05. However, there was no significant difference between the maltreated and nonmaltreated groups with respect to children’s church attendance or parents’ church attendance and importance of faith.

Table 2.

Comparison of Maltreated and Nonmaltreated Groups on Parent and Child Religiosity and Child Behavioral Adjustment

| Maltreated (N = 170) |

Nonmaltreated (N = 159) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range | t |

| Child Religiosity | |||||

| Church Attendance | 3.06 (1.56) | 1–5 | 3.09 (1.49) | 1–5 | .17 |

| Importance of Faith | 4.30 (1.22) | 1–5 | 4.52 (.85) | 1–5 | 1.93(*) |

| Parent Religiosity | |||||

| Church Attendance | 2.68 (1.45) | 1–5 | 2.63 (1.47) | 1–5 | −.30 |

| Importance of Faith | 3.85 (1.52) | 1–5 | 3.80 (1.59) | 1–5 | −.28 |

| Child Behavioral Adjustment | |||||

| Internalizing | 48.36 (7.91) | 36.00–72.00 | 46.84 (7.30) | 36.00–68.50 | −1.80 |

| Externalizing | 54.22 (9.51) | 39.00–80.00 | 52.09 (8.98) | 39.00–77.50 | −2.08* |

Note.

p < .05;

p = .05

We used the APIM with parent-child dyads as a unit of analysis to test whether parents’ religiosity and interaction of religiosity between parents’ and children’s religiosity make unique contributions to predicting child behavioral adjustment beyond the contribution of children’s own religiosity. In the APIMs, the actor effect was shown as the effect of children’s religiosity on child outcomes whereas the partner effect was shown as the effect of parents’ religiosity on child outcomes. We also tested whether the effect of parents’ religiosity on child behavioral adjustment was moderated by the level of children’s religiosity (i.e., actor-partner interaction). The main effect variables of parents’ and children’s religiosity were centered prior to conducting the path analysis in order to reduce the multicollinearity between predictors and their interaction terms. The interaction between parents’ and children’s religiosity was computed by multiplying parents’ religiosity by children’s religiosity. In the path models, religiosity predictors (parents’ religiosity, children’s religiosity, and the parent-child religiosity interaction) were allowed to covary with one another, and measurement errors were allowed to be correlated with each other between internalizing and externalizing symptomatology.

Multiple group SEM analyses were conducted in order to test if the influences of parents’ religiosity, children’s religiosity, and parent-child religiosity interaction on child behavioral adjustment outcomes differ between maltreated and nonmaltreated groups and between boys and girls. In these four group SEM analyses, parameters were simultaneously estimated for four gender-by-maltreatment covariance matrices. Table 3 presents Pearson product-moment correlations of parents’ and children’s religiosity and child internalizing and externalizing symptomatology separately for the four groups of maltreated boys, maltreated girls, nonmaltreated boys, and nonmaltreated girls.

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations among Parents’ and Children’s Religiosity for Maltreated and Nonmaltreated Boys and Girls

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonmaltreated (N = 159 dyads; 69 boys and 90 girls) | ||||||

| 1. Children’s Church Attendance | .05 | .55* | .36* | −.10 | −.03 | |

| 2. Children’s Importance of Faith | .18 | .04 | −.03 | .13 | .04 | |

| 3. Parents’ Church Attendance | .51* | .12 | .69* | −.19+ | .10 | |

| 4. Parents’ Importance of Faith | .30* | .22+ | .67* | −.16 | .13 | |

| 5. Child Internalizing Symptomatology | −.13 | .11 | −.12 | .14 | −.02 | |

| 6. Child Externalizing Symptomatology | −.25* | −.15 | −.23+ | −.33* | .47* | |

| Maltreated (N = 170 dyads; 99 boys and 71 girls) | ||||||

| 1. Children’s Church Attendance | .07 | .32* | .11 | −.13 | .13 | |

| 2. Children’s Importance of Faith | .29* | .03 | .18 | −.27* | −.08 | |

| 3. Parents’ Church Attendance | .17+ | .18+ | .66* | −.06 | −.03 | |

| 4. Parents’ Importance of Faith | .13 | .12 | .66* | .05 | −.02 | |

| 5. Child Internalizing Symptomatology | .14 | −.06 | .07 | .08 | .11 | |

| 6. Child Externalizing Symptomatology | .02 | .06 | −.20* | −.10 | .05 | |

Note. Correlations of boys are below the diagonal and correlations of girls are above the diagonal.

p < .05;

p < .10.

A series of hierarchically related (nested) models were tested to examine the invariance of parameters across the four groups. More specifically, in the Configural Invariance model, all parameters were freely estimated to test whether the patterns of structural relations, rather than the actual numerical values, were invariant between the two groups. This configural invariance model was the least restricted model among the models tested. In the Equal Gender Effect model, equality constraints were imposed to test numeric invariance of the parameters for the effects of parents’ and children’s religiosity and the interaction between parents’ and children’s religiosity on child behavioral adjustment between two gender groups within the maltreated or the nonmaltreated group (e.g., maltreated boys = maltreated girls; nonmaltreated boys = nonmaltreated girls). Finally, in the Equal Maltreatment Effect model, cross-group equality constraints were imposed between the maltreated and the nonmaltreated groups for the effects of parents’ and children’s religiosity and the interaction on child outcomes. The adequacy of the equality constraints were tested using nested chi-square difference tests (Bollen, 1989).

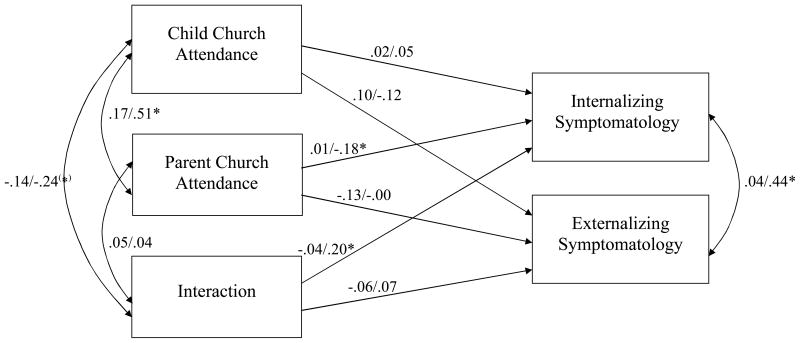

The results of a nested modeling comparison are summarized in Table 4. For the APIM with parents’ and children’s church attendance, the equality constraints across gender did not lead to a significant decrement in model fit. The result indicated that the effects of parents’ and children’s church attendance and their interaction on child behavioral adjustment were similar between boys and girls within the maltreated or the nonmaltreated group. We further imposed equality constraints between the maltreated and the nonmaltreated groups, and these additional equality constraints degraded the model fit. The result suggested that the effects of parents’ and children’s church attendance and their interaction on child internalizing and externalizing symptomatology differed significantly between the maltreated and the nonmaltreated groups. As shown in Figure 1, the best-fitting model (the Equal Gender Effect model) indicated that the interaction effect between parents’ and children’s church attendance was significant for internalizing symptomatology among nonmaltreated children (B = .76, SE = .30, p < .05). In addition, in the nonmaltreated group, parents’ church attendance was significantly related to lower levels of internalizing symptomatology among their children (B = −.95, SE = .46, p < .05). In contrast, parents’ and children’s church attendance and their interaction were not significantly predictive of child behavioral adjustment in the maltreated group.

Table 4.

Comparative Goodness-of-Fit of Four-Group Structural Equation Models for Religiosity and Behavioral Adjustment

| Model Label | χ2 | df | p(exact) | CFI | RMSEA | p(close) | Δχ2 | Δdf | p(d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Church Attendance Predicting Internalizing and Externalizing Symptomatology | |||||||||

| Configural Invariance | 0 | 60 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Equal Gender Effect | 12.57 | 12 | .40 | .99 | .01 | .89 | 12.57 | 12 | .40 |

| Equal Maltreatment Effect | 25.37 | 18 | .12 | .93 | .04 | .76 | 12.80 | 6 | < .05 |

| Importance of Faith Predicting Internalizing and Externalizing Symptomatology | |||||||||

| Configural Invariance | 0 | 60 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Equal Gender Effect | 16.20 | 12 | .18 | .96 | .03 | .74 | 16.20 | 12 | .18 |

| Equal Maltreatment Effect | 28.95 | 18 | .05 | .88 | .04 | .61 | 12.74 | 6 | < .05 |

Note. p(exact) = probability of an exact fit to the data; CFI = comparative-fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; p(close) = probability of a close fit to the data; Δχ2 = difference in likelihood ratio tests; Δdf = difference in df; p(d) = probability of the difference tests.

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood estimation (standardized coefficients) of a path model for parent and child church attendance and their interaction predicting child internalizing and externalizing symptomatology. Maltreated group is on left and nonmaltreated group is on right.

* p < .05; (*) p = .05.

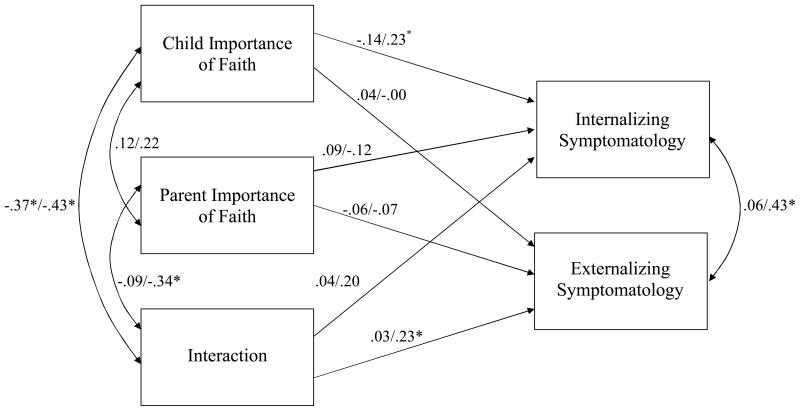

Similar to the APIM of church attendance, the Equal Gender Effect model was the best-fitting model for the APIM involving parents’ and children’s importance of faith (see Table 4). This result suggests that there were no significant gender differences with respect to the effects of parents’ and children’s importance of faith and their interaction on child internalizing and externalizing symptomatology. However, there were significant differences between the maltreated and the nonmaltreated groups with respect to the main and interactive effects of parents’ and children’s importance of faith on child outcomes. As can be seen in Figure 2, the interaction between parents’ and children’s importance of faith was associated with externalizing symptomatology among nonmaltreated children (B = 1.04, SE = .48, p < .05). In addition, the interaction effect was marginally significant for internalizing symptomatology among nonmaltreated children (B = .69, SE = .37, p = .07). The findings indicated that the effects of parents’ importance of faith on child maladjustment varied depending upon the level of children’s importance of faith. There were no main effects of children’s importance of faith in the maltreated group. In the nonmaltreated group, however, children’s importance of faith was positively related to internalizing symptomatology (B = 1.64, SE = .71, p < .05). We further tested whether this counter-intuitive regression coefficient can be explained by the presence of suppression effects. We examined a path model that estimated covariance coefficients (instead of regression coefficients) between the predictors of parents’ and children’s importance of faith and the outcome of internalizing symptomatology. The result indicated that children’s importance of faith was not significantly associated with internalizing symptomatology (B = .81, SE = .49, p = .10), whereas parents’ importance of faith is negatively correlated with internalizing symptomatology with a marginal significance (B = −1.75, SE = .93, p = .06). It appeared that the regression coefficient of children’s importance of faith on internalizing symptomatology became significant in the presence of other predictors (such as parents’ importance of faith and the interaction between parents’ and children’s religiosity), suggesting the possibility of suppression effects (Darlington, 1968; MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000).

Figure 2.

Maximum likelihood estimation (standardized coefficients) of a path model for parent and child importance of faith and their interaction predicting child internalizing and externalizing symptomatology. Maltreated group is on left and nonmaltreated group is on right.

* p < .05.

The degree of interdependence of parent-child religiosity was examined by the correlations between parents’ and children’s religiosity in the APIMs (Kenny et al., 2006). The correlation between parents’ church attendance and children’s church attendance was significantly higher for the nonmaltreated group (r = .51, p < .05) than the maltreated group (r = .17, p = .10), Z = 3.51, p <.05. Similarly, the degree of parent-child concordance in importance of religious faith appeared higher for the maltreated group (r = .22, p = .07) compared to the nonmaltreated group (r = .12, p = .24), although the difference between these two correlations was not statistically significant, Z = 1.02, p = .31.

Significant interactions were followed by testing simple effects in order to identify the nature of the moderated effects that were obtained. We divided the sample into two groups according to the level of children’s religiosity and examined the effect of parents’ religiosity on behavior adjustment. First we tested the effect of parents’ church attendance on internalizing symptomatology among nonmaltreated children separately for the low church attendance group (i.e., nonmaltreated children whose church attendance score was below the group mean, n = 77) and the high church attendance group (i.e., nonmaltreated children whose church attendance score was equal to or greater than the group mean, n = 82). The results revealed that higher parents’ church attendance was significantly predictive of internalizing symptomatology in the low church attendance group (B = −1.76, SE = .64, p < .05), whereas parents’ church attendance was not significantly related to internalizing symptomatology in the high church attendance group (B = −.24, SE = .59, p = .69).

Similarly, with respect to importance of faith, higher parents’ importance of faith was significantly predictive of internalizing symptomatology (B = −1.80, SE = .64, p < .05) and externalizing symptomatology with a marginal significance (B = −1.81, SE = .93, p = .06) in the low faith group (i.e., nonmaltreated children whose importance of faith score was below the group mean, n = 49). However, parents’ importance of faith was not significantly related to either internalizing symptomatology (B = −.22, SE = .43, p = .61) or externalizing symptomatology (B = .10, SE = .49, p = .84) in the high faith group (i.e., nonmaltreated children whose importance of faith score was equal to or greater than the group mean, n = 110).

Discussion

The current investigation examined independent effects of parents’ and children’s religiosity and the interdependence between parents’ and children’s religiosity on behavioral adjustment among high-risk children with or without earlier maltreatment experiences. Our findings suggested that among nonmaltreated children, parents’ religiosity was significantly predictive of child behavioral adjustment, especially when children’s religiosity was lower. In addition, the interdependence between parents’ and children’s religiosity was stronger for the nonmaltreated group than the maltreated group.

The protective effects of parents’ religiosity found in this study suggest differential roles of parents’ religiosity in the development of internalizing and externalizing symptomatology between maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Specifically, parents’ religiosity seems to be more influential for child adjustment outcomes when the parent-child relationship is more positive. Only for the nonmaltreated group, children whose parents reported higher importance of faith showed lower levels of externalizing and internalizing symptomatology, and those whose parents reported higher church attendance showed lower levels of internalizing symptomatology. More importantly, the evidence of parent-child religiosity interaction suggested that parents’ religiosity exerted stronger protective effects when children’s religiosity was low. Parents’ frequent church attendance was related to lower levels of internalizing symptomatology among their children, especially when the children’s reports of church attendance were low. This finding is consistent with the previous findings by Bartkowski et al. (2008) showing that religious attendance of parents was related to lower levels of adjustment problems, such as internalizing and externalizing symptomatology, in the national sample from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study. The current study provides further evidence that the protective effects of parents’ religiosity were particularly strong when children’s religiosity was low.

We found that higher levels of parents’ importance of faith were associated with lower levels of child externalizing symptomatology only among nonmaltreated children who reported lower levels of importance of faith. This finding suggests that religious behaviors and beliefs offered by parents have protective effects against child externalizing symptomatology as social control theory predicts. It is plausible that religious parents may be better in their monitoring of their children’s behaviors (e.g. Brody & Flor, 1998; Gunnoe et al., 1999), which in turn results in reduced levels of externalizing symptomatology. Research to directly investigate the role of parental monitoring behaviors in accounting for the link between parents’ religiosity and child externalizing symptomatology would be informative.

Our data demonstrated that parent reports on both church attendance and importance of faith were related to lower levels of internalizing symptomatology among nonmaltreated children with low religiosity. Prior studies have demonstrated a positive relationship between parents’ religiosity and the warmth and emotional support provided by parents (Brody & Flor, 1998; Gunnoe et al., 1999). In addition, more religious parents seem to have more satisfying relationships with their children. In a study examining the impact of family religious life on mother-child relationship, mothers’ view of the importance of religion had a strong positive effect on their report of the mother-child relationship quality and was also related to children’s reports of the mother-child relationship quality (Pearce & Axinn, 1998). As Mahoney and colleagues suggested, religious involvement may provide a cultural resource within a family that can be used to resolve conflicts and enhance cohesion among its members (Mahoney, Pargament, Murray-Swank, & Murray-Swank, 2003). In light of these previous findings, it may be that parents’ religiosity promoted more positive parenting behaviors, and more positive parent-child relationships were associated with lowered internalizing symptomatology among their children. Future research will need to examine parental emotional support and involvement to test the possibility of the mediational link between parents’ religiosity and child internalizing symptomatology through parenting characteristics.

Given that parents provide a considerable share of their children’s internalized values (Regnerus, 2003b), some shared religious practices and similar religious beliefs between parents and children were expected. Our data revealed that the evidence for shared religious practices between parents and children was stronger in nonmaltreating families than in maltreating families. This finding is consistent with conclusions drawn from prior research that intergenerational transmission is more likely to occur in the families with more positive parent-child relationships (e.g., Bao et al., 1999). Research has shown that experiences of poor quality caregiving are related to the development of negative representational models of attachment figures (Cicchetti, 1991; Crittenden & Ainsworth, 1989). Child maltreatment reflects an extreme of caregiving dysfunction, and a greater percentage of insecure attachment relationships with primary caregivers have been documented among maltreated children (Crittenden, 1988; Toth & Cicchetti, 1996). We speculate that insecure attachment and poor quality parent-child relationships in maltreating families may explain why shared religious practices are less likely to appear in maltreating families than in nonmaltreating families. In the current sample, about nine percent of maltreated children were in foster or kinship care; therefore, interpretations involving assumptions about the parenting practices of caregivers in the maltreated group should be made cautiously with such a caveat in mind.

In addition, interdependence between parents’ and children’s religiosity was stronger for church attendance than for importance of faith. This is consistent with the results from a longitudinal study of depressed and non-depressed mothers and offspring by Miller, Warner, Wickramaratne, & Weissman (1997) that demonstrated higher levels of mother-offspring concordance in church attendance compared to mother-offspring concordance in importance of religion (when the offspring were young adults).

Our data indicated that maltreated children reported lower levels of importance of faith than nonmaltreated children; however, the two groups did not differ in terms of the frequency of church attendance. Thus, the finding is only partially supportive of previous studies with adults that indicated a significant influence of child maltreatment on religiosity (e.g., Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1989; Hall, 1995; Kane, Cheston, & Greer, 1993). For example, adults who experienced maltreatment committed by fathers during childhood were lower in religious involvement (Bierman, 2005). This finding indicated that the victims of paternal maltreatment may form a negative view of God, often identified as a paternal figure, and hence result in a lower level of religious involvement. It may be that the nonsignificant difference in church attendance between maltreated and nonmaltreated children is in part due to the fact that children’s church attendance may largely reflect the family’s or the parents’ church attendance rather than children’s own volition. Our findings extend previous research on the link between maltreatment and religiosity by examining the associations between maltreatment and the two independent yet correlated dimensions of religiosity (i.e., church attendance and importance of faith) in childhood.

From a measurement perspective, our findings point out that it is important to involve diverse dimensions of religiosity measures. The two measures of church attendance and importance of faith used in this study showed differential effects on children’s adjustment. This finding indicates that the different measures of religiosity used in the present study represent independent variance of religiosity. In addition, the result is largely consistent with the viewpoint that organizational religiosity (such as church attendance) and personal religiosity (such as importance of faith) represent separate religious dimensions (e.g., George, Ellison, & Larson, 2002).

Several limitations of the present study suggest directions for future research. First, more systematic and comprehensive theoretical and empirical examination is required regarding the protective effects of parents’ and children’s religiosity in the development of children at risk. Additional studies are needed to identify processes by which religiosity affects developmental outcomes of earlier child maltreatment experiences by promoting resilience and reducing negative adjustment. For example, research on the mechanisms by which religiosity exerts its buffering effects on behavioral maladjustment may include some personality factors, especially the self-system, such as self-concept and self-regulation (e.g., George et al., 2002; McCullough & Willoughby, 2009). An additional caveat is that the data for this study were cross-sectional. Therefore, causality in the relations between parents’ and children’s religiosity and child behavioral adjustment could not be verified in the structural equation models. Replications and extensions of our design are encouraged. Particularly, future studies with prospective longitudinal designs will make it possible to examine how religious protective processes change with development across life span. Finally, in future studies, it is recommended to consider individual characteristics and contextual factors that may determine the roles of religiosity as protective or risk factors (e.g. Crawford, Wright, & Masten, 2006). Unlike the findings of this study, which showed both parents’ and children’s religiosity as protective factors, religiosity may be a risk factor for some individuals in some contexts (e.g., Bartkowski et al., 2008).

We found that parents’ religiosity makes significant contributions (independent of children’s own religiosity) to protecting nonmaltreated children from developing internalizing and externalizing symptomatology, especially when children’s religiosity is low. The findings of this study enhance our understanding of the role of parents’ religiosity by demonstrating that the protective role of parents’ religiosity varied by parent-child relationship quality (reflected on maltreatment) and children’s religiosity. The results illustrate the utility of future research involving the transactions of risk and protective processes in both child and familial levels in studying developmental pathways to maladaptation. Such work promises to generate new knowledge that will be useful for the development of effective prevention and intervention programs. Particularly, this study’s findings indicate that a range of parents’ and children’s religious behaviors and practices can be assessed in translational prevention research. It is recommended that healthcare professionals, psychologists, and social workers working with high-risk children and their families consider the role religiosity plays in the development of prevention and intervention programs to alleviate distress and enhance stress coping.

Contributor Information

Jungmeen Kim, Email: jungmeen@vt.edu, Department of Psychology, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA 24061.

Michael E. McCullough, Department of Psychology, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL 33124

Dante Cicchetti, Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the teacher’s report form and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bao WN, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Conger RD. Perceived parental acceptance as a moderator of religious transmission among adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:362–374. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In: Cicchetti D, Toth S, editors. Child abuse, child development, and social policy: Advances in applied developmental psychology. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing; 1993. pp. 7–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowski JP, Wilcox WB. Conservative Protestant child discipline: The case of parental yelling. Social Forces. 2000;79:263–290. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowski JP, Xu X, Levin ML. Religion and child development: Evidence from the early childhood longitudinal study. Social Science Research. 2008;37:18–36. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Child maltreatment and optimal caregiving in social contexts. New York: Garland Publishing; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman A. The effects of childhood maltreatment on adult religiosity and spirituality: Rejecting God the father because of abusive fathers? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2005;44:349–359. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ. Pathways from child maltreatment to internalizing problems: Perceptions of control as mediators and moderators. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:913–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL. Maternal resources, parenting practices, and child competence in rural, single-parent African American families. Child Development. 1998;69:803–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Stoneman Z, Flor DL. Parental religiosity, family processes, and youth competence in rural two-parents African American Families. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:696–706. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo RK. Parent religiosity, family process, and adolescent outcomes. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services. 2004;85:495–510. [Google Scholar]

- Carothers SS, Borkowski JG, Lefever JB, Whitman TL. Religiosity and the socioemotional adjustment of adolescent mothers and their children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:263–275. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. Fractures in the crystal: Developmental psychopathology and the emergence of self. Developmental Review. 1991;11:271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Manly JT. A personal perspective on conducting research with maltreating families: Problems and solutions. In: Sigel I, Brody GH, editors. Methods of family research: Biographies of research projects: Volume 2. Clinical Populations. Hillside, NJ: Erlbaum; 1990. pp. 87–133. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. The impact of child maltreatment and psychopathology on neuroendocrine functioning. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:783–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth S. Child maltreatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:409–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford E, Wright MO, Masten AS. Resilience and spirituality in youth. In: Roehlkepartain E, King P, Wagner L, Benson P, editors. The handbook of spiritual development in children and adolescence. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2006. pp. 355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PM. Relationships at risk. In: Belsky J, Nezworski T, editors. Clinical maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 136–174. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PM, Ainsworth M. Attachment and child abuse. In: Cicchetti D, Carlson V, editors. Child maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989. pp. 432–463. [Google Scholar]

- Darlington R. Multiple regression in psychological research and practice. Psychological Bulletin. 1968;69:161–182. doi: 10.1037/h0025471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. How the experience of early physical abuse leads children to become chronically aggressive. In: Cicchetti D, Toth S, editors. Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology: Vol. 8. The effects of trauma on the developmental process. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1997. pp. 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio BM, Eaves LJ, Murrelle L, Maes HH, Spilka B. Understanding biological and social influences on religious affiliation, attitudes and behaviors: A behavior genetic perspective. Journal of Personality. 1999;67:953–984. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Hotaling GT, Lewis IA, Smith C. Sexual abuse and its relationship to later sexual satisfaction, marital status, religion, and attitudes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1989;4:379–399. [Google Scholar]

- Flor DL, Knapp NF. Transmission and transaction: Predicting adolescents’ internalization of parental religious values. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:627–645. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.4.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Ellison CG, Larson DB. Explaining the relationships between religious involvement and health. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13:190–200. [Google Scholar]

- Granqvist P. Attachment and religiosity in adolescence: Cross-sectional and longitudinal evaluations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:260–270. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnoe ML, Hetherington EM, Reiss D. Parental religiosity, parenting style, and adolescent social responsibility. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:199–225. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnoe ML, Moore KA. Predictors of religiosity among youth aged 17–22: A longitudinal study of the national survey of children. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41:613–622. [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. Spiritual effects of childhood sexual abuse in adult Christian women. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 1995;23:129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T, Stark R. Hellfire and delinquency. Social Problems. 1969;17:202–213. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AF. Four factor index of social status. Yale University; 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Kane D, Cheston SE, Greer J. Perceptions of God by survivors of childhood sexual abuse: An exploratory study in an under-researched area. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 1993;21:228–237. [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK, Howe TR, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. The timing of child physical maltreatment: A cross-domain growth analysis of impact on adolescent externalizing and internalizing problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:891–912. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guildford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. The protective effects of child and parent religiosity on maladjustment among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2008;32:711–720. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig LB, McGue M, Krueger RF, Bouchard TJ. Genetic and environmental influences on religiousness: Findings for retrospective and current religiousness ratings. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:471–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner R, Galambos N. Adolescent development: Challenges, and opportunities for research, programs and policies. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:413–446. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1:173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Pargament KI, Murray-Swank A, Murray-Swank N. Religion and the sanctification of family relationships. Review of Religious Research. 2003;44:220–236. [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children’s adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Nieri T, Parsai M. God forbid! Substance use among religious and nonreligious youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:585–598. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Willoughby BLB. Religion, self-regulation, and self-control. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:69–93. doi: 10.1037/a0014213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LW, Warner V, Wickramaratne P, Weissman M. Religiosity and depression: Ten-year follow-up of depressed mothers and offspring. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:1416–1425. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199710000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers SM. An interactive model of religiosity inheritance: The importance of family context. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:858–866. [Google Scholar]

- Ozorak EW. Social and cognitive influences on the development of religious beliefs and commitment in adolescence. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1989;28:448–463. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce LD, Axinn WG. The impact of family religious life on the quality of mother-child relations. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:810–828. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce LD, Haynie DL. Intergenerational religious dynamics and adolescent delinquency. Social Forces. 2004;82:1553–1572. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce MJ, Jones SM, Schwab-Stone ME, Ruchkin V. The protective effects of religiousness and parent involvement on the development of conduct problems among youth exposed to violence. Child Development. 2003;74:1682–1696. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce MJ, Little TD, Perez JE. Religiousness and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:267–276. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3202_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus MD. Linked lives, faith, and behavior: Intergenerational religious influence on adolescent delinquency. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2003a;42:189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus MD. Religion and positive adolescent outcomes: A review of research and theory. Review of Religious Research. 2003b;44:394–413. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus MD, Elder GH., Jr Staying on track in school: Religious influences in high- and low-risk settings. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2003;42:633–649. [Google Scholar]

- Schapman AM, Inderbitzen-Nolan HM. The role of religious behaviour in adolescent depressive and anxious symptomatology. Journal of Adolescence. 2002;25:631–643. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. Theorizing religious effects among American adolescents. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2003;42:17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Cicchetti D. Patterns of relatedness, depressive symptomatology, and perceived competence in maltreated children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:32–41. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigert AJ, Thomas DL. Parental support, control and adolescent religiosity: An extension of previous research. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1972;11:389–393. [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE, Smith RS. Vulnerable but invincible: A study of resilient children. New York: McGraw- Hill; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox WB. Conservative Protestant childrearing: Authoritarian or authoritative? American Sociological Review. 1998;63:796–809. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox WB. Religion, convention, and paternal involvement. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:780–792. [Google Scholar]

- Wright LS, Frost CJ, Wisecarver SJ. Church attendance, meaningfulness of religion, and depressive symptomatology among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1993;22:559–568. [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski DS, Bradshaw CP. Ecological influences on the sequelae of child maltreatment: A review of the literature. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11:49–62. doi: 10.1177/1077559505283591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]