Abstract

The retinoic acid receptor-α (Rara) gene is critical for germ cell development in the testis, as demonstrated by infertile Rara knockout male mice. The encoded protein for Rara (RARA) is expressed in both Sertoli cells and germ cells, but it is not always in the nucleus. Previously, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) was shown to increase the nuclear localization and transcriptional activity of RARA in Sertoli cells. Here, we identified a small ubiquitin-like modifier-2 (SUMO-2) modification as a novel posttranslational regulatory mechanism controlling the ATRA-dependent RARA subcellular localization and transcription. ATRA increased the SUMO-2 modification of RARA. In the presence of ATRA, lysine 166 (K166) and K171 of RARA were modified at a physiological concentration of SUMO-2, whereas in the absence of ATRA, K399 was the only site that was modified, but at a higher SUMO-2 concentration. However, K399 was critical for ATRA-controlled nuclear trafficking of RARA. In the presence of ATRA, a K399 mutation to arginine resulted in the cytoplasmic localization of K399R mutant, indicating that K166 and K171 sumoylations were inhibitory to nuclear localization. This may be due to SUMO/sentrin-specific peptidase 6 (SENP6) not being able to bind K399R mutant to desumoylate K166 and K171 in Sertoli cells, whereas it can bind RARA with intact K399. On the other hand, functional K166 and K171 sites for sumoylation were required for a full transcriptional activity, when K399 was intact. These results together suggest that both K166 and K171 sumoylation and desumoylation are critical for optimal RARA function.

SUMO-2 modification of retinoic acid receptor α (RARA) regulates the function of RARA.

The retinoic acid receptor-α gene (Rara) is critical for spermatogenesis, as shown by a sterility phenotype in null mutant males (1). The testes of Rara-null mutants displayed testicular degeneration and increased apoptosis in early meiotic spermatocytes (2). The protein for Rara (RARA) was expressed in both Sertoli cells and germ cells (3,4). [The gene and protein nomenclature approved by the International Committee on Standardized Genetic Nomenclature for Mice (http://www. informatics.jax.org/mgihome/nomen/gene.shtml) were used.] RARA may function in Sertoli cells to promote the survival and development of early meiotic prophase spermatocytes, whereas RARA in germ cells may function to increase the proliferation and differentiation of spermatogonia before or around meiotic prophase (2). Thus, it is important to understand how RARA is regulated in the testis.

Unlike other type II steroid/thyroid hormone receptors, RARA is not found in the nucleus of testicular cells throughout development (4). The nuclear trafficking is regulated by its ligand, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) (5). In addition, posttranslational modifications of RARA play a major role in the regulation of its subcellular localization, degradation, and transcriptional activity (6,7,8,9). For example, FSH, via cAMP and protein kinase A, inhibited ATRA-induced endogenous RARA nuclear localization, reduced the steady-state level of RARA, and decreased the retinoic acid-responsive element (RARE)-dependent transcription in a mouse Sertoli cell line (MSC-1) stably transfected using the FSH receptor cDNA (6). Another study showed that endogenous RARA can be positively regulated by protein kinase C and MAPK in Sertoli cells, independent of the ligand (7). Moreover, phosphorylation of RARA by cyclin-dependent kinase 7 in the N-terminal A/B region of RARA that harbors the ligand-independent activation function-1 domain, was required for ATRA-induced ubiquitylation of the receptor and degradation by proteasomes (8,9).

Previously, we have performed yeast two-hybrid screening using RARA as the bait and the protein products of a primary Sertoli cell cDNA expression library as the prey to identify the molecular players interacting with RARA in Sertoli cells (unpublished data). One of the candidates from the screen was small ubiquitin-like modifier-2 (SUMO-2).

There are four known members in the SUMO family. SUMO-2 and -3 share 95% amino acid sequence identity, and each shares about 47% sequence identity with SUMO-1. Sumoylation entails a covalent attachment of SUMO, ligated by an isopeptide bond to a lysine residue within the sumoylation motif of protein targets (10). In addition, SUMO-2 and -3 have their own sumoylation sites, and thus they can form a SUMO-2/3 polychain (10), whereas SUMO-1 cannot form a polychain. As for SUMO-4, it may function exclusively as a noncovalent interacting protein (11), with a restricted pattern of expression (12).

Sumoylation, similar to ubiquitinylation, occurs through a three-step enzymatic process: SUMO activation by the E1 enzyme, AOS1/UBA2 (SAE1/SAE2); SUMO conjugation to the target substrate by the E2 enzyme, UBE2I (UBC9); and SUMO ligation by E3-like ligases, which are thought to be substrate specific (10). Recently, it was shown that the SUMO-2/3 polychain may be built and then transferred en bloc to the substrate and that the RAN binding protein 2 and the protein inhibitors of active STAT (PIAS) family of E3-like ligases may stimulate this multimerization process (13,14). In reverse, members of a family of SUMO/sentrin-specific peptidases (SENPs) function to remove SUMO from the target protein (15). Some SENPs are involved in proteolytic activation of SUMO precursors, some only desumoylate the first SUMO linked to the target protein or some can desumolyate (edit) a SUMO-2/3 from another SUMO-2/3 on a polychain (16). In addition, SENPs have specific subcellular localization. For example, SENPs can be located specifically in the nuclear side of the nuclear pore complex, in the nucleoplasm, in the nucleolus, or in the cytoplasm (17).

Sumoylation has been reported to regulate cell cycle progression, transcription, nuclear-cytoplasmic transport, protein stability, and protein-protein interactions (10). In the testis, SUMO-1, SUMO-2/3, and UBC9 are demonstrated to be expressed in male germ cells during meiosis and in spermiogenesis (18). It has been postulated that SUMO-1 is involved in heterochromatin organization, meiotic centromere function, and nuclear reshaping (19) and SUMO-2/3 in the metaphase I function of spermatocytes (18). Moreover, human patients with SUMO-2/3 hyposumoylation or hypersumoylation were found to have azoospermia, hypospermatogenesis, or reduction in spermatogenesis (20).

However, the functional consequences of sumoylation are substrate specific, and it is important to investigate SUMO-2/3 substrates in the testis. More specifically, the expression and the target proteins of SUMO-2, which can form a SUMO-2 polychain, are poorly understood in Sertoli cells. Here, we demonstrate that RARA is a substrate of SUMO-2 in Sertoli cells and COS-7 cells and that a dynamic process of sumoylation and desumoylation influences the subcellular localization and transcriptional activity of RARA.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid constructs

A human RARA (hRARA) cDNA from LRARaSN (21) was subcloned into the pFLAG-CMV2 vector (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) using EcoRI and BamHI. To mutate specific residues in hRARA cDNA, the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used. The entire resulting cDNAs were sequenced to confirm the site-directed mutations. pFLAG-Sumo-2 and pHis-Sumo-2 cDNAs were constructed by inserting the full-length rat Sumo-2 cDNA into pFLAG-CMV-2 and pQE-TriSystem, respectively (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA).

Antibodies and reagents

An affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against a full-length SUMO-2 protein recognized both SUMO-2 and -3 (Zymed Laboratories, Inc., San Francisco, CA). Anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-SENP6 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), and an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal anti-RARA antibody raised against a human RARA peptide consisting of amino acids 443-462 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used. Am580, a RARA-specific agonist (Biomol Research Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA), was purchased. Recombinant human FSH was obtained from Dr. A. F. Parlow, National Hormone and Peptide Program (Torrance, CA).

Vitamin A-deficient (VAD) rats

Male Sprague Dawley rats, 30–40 g body weight, were placed on a VAD diet (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) at postnatal d 20. Testes were collected after 9 wk on VAD diet. To obtain retinol-replenished animals, the VAD animals were injected with 7.5 mg all-trans retinol in 50% ethanol, followed by a dietary supplementation of 1 mg retinol per animal mixed with normal rodent diet (Harlan Teklad). Testes were collected after 4, 8, or 24 h after retinol injection. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Washington State University.

Cell isolation and culture

MSC-1 and COS-7 cells were maintained at 37 C in DMEM supplemented with penicillin (100 IU/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and either 5 or 10% fetal bovine serum, respectively. Primary Sertoli cells were isolated from the testes of 20-d-old rats by sequential enzymatic digestions, as previously described (7). Sertoli cells were plated under serum-free conditions in Ham’s F-12 medium (Invitrogen Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA) and cultured at 32°C for up to 72 h. Germ cells from four adult male rats (∼60 d of age) were isolated using collagenase and trypsin as previously described (22). To determine the percentage of germ cells, the isolated cells were smeared onto a slide, fixed with Bouin’s solution for 1 h, and stained with hematoxylin. Counting more than 200 cells per preparation, the average percentage of germ cells in three separate germ cell preparation was 84.3 ± 0.7% (mean ± sd).

Concentration of immunoprecipitated proteins from Sertoli cells

Primary Sertoli or MSC-1 cells from three 150-mm plates were lysed in a buffer containing 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). After 20 min on ice, the cells were centrifuged at 750 × g for 5 min, and the pellet was lysed in cold nuclear lysis buffer consisting of 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 420 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 100 mm EDTA (pH 8.0), 20% glycerol, 10% sucrose, and protease inhibitors. Then, 1 mg of the lysate was loaded on a column packed with 2 ml anti-RARA antibody cross-linked to protein A agarose beads with dimethylpimelinidate triethlyamine (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated for 3 h. The column was washed extensively, and bound proteins were eluted with 200 μl elution buffer (20 mm triethlyamine and 10% glycerol). When eluted proteins were further concentrated, 0.25 vol ice-cold trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (100% mass/vol) and 4 mg/ml sodium deoxycholate were added, incubated on ice for 30 min, and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed with acetone (−20°C), incubated on ice for 10 min, and then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4 C. The final pellet was air dried and resuspended in SDS-PAGE loading buffer for Western blot analysis.

Transient transfection and immunoprecipitation analysis

COS-7 cells, 75% confluent, in 60-mm plates were transfected with 1:1 ratio (6 μg total per plate) of pFLAG-RARA and pFLAG-Sumo-2 cDNA constructs using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). At 48 h after transfection, the cells were lysed in modified RIPA buffer [50 mm Tris/HCl (pH7.4), containing 150 mm NaCl, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 10% SDS, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and a protease inhibitor], and the lysates were processed with True Blot IP system according to the manufacturer’s instructions (eBiosciences, Inc., San Diego, CA). Anti-RARA antibody or anti-SUMO-2/3 antibody was cross-linked to protein G-Sepharose beads. Immunoprecipitates were washed extensively and subjected to Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis

Equal amounts of proteins (30–50 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore Co., Bedford, MA), as described previously (7). After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.5% Tween (0.5% TBST) for 1 h, membranes were incubated with primary antibody and then with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody both in 0.5% TBST for 1 h at room temperature. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay with BSA as the standard. Equal loading was mostly determined using Coomassie blue dye-stained membrane, which detects many unspecified bands instead of one specific protein. Equal loading was also determined by Western blot analysis with anti-actin antibody. Blots were processed with enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting system (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Transient transfection and indirect immunofluorescence assay

COS-7 and primary Sertoli cells were seeded on coverslips, transfected with various cDNA constructs, if needed, allowed to recover for 48 h, and treated with various reagents for 30 min and fixed in −20 C methanol for 10 min. For immunostaining, the fixed cells were blocked with 10% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h, incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 C, and incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody at 1:300 dilutions for 1 h at room temperature. Detection of antibody complexes was conducted using fluorescein avidin D (Vector). All digital images were obtained using a laser confocal system (Zeiss LSM 510, Hitachi, Japan).

Transient transfection and luciferase reporter assay

MSC-1 and COS-7 cells, 75% confluent, were transfected with various cDNA constructs. The luciferase reporter plasmid, pRARE-tk-Luc, which contains three RAREs from the RARB promoter, and pcDNA-β-gal were described previously (6). In all cases, the total amounts of DNA were adjusted to the same amount using the empty vector plasmid, pcDNA-3.1(−) (Invitrogen). Transfected cells were allowed to recover for 24 h and then cultured for an additional 24 h, during which time the cells were treated with appropriate reagents, if needed. After that, cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity using a luciferase assay system (Promega Co., Madison, WI). The β-galactosidase activity, used for transfection efficiency, was determined with the galactosidase assay system (Promega).

RNA extraction and real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA from isolated Sertoli cells, germ cells, and the testes from VAD rats were collected using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Real-time RT-PCR primers for Sumos and Senps (Table 1) were designed using Primer Express software version 2.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). cDNA was synthesized from 500-ng RNA samples using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Subsequently, 20 ng cDNA was used as a template for real-time PCR assays with a Gene Amp 7000 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). Cycle threshold (Ct) values for Sumos, Senps, and the housekeeping gene S2 were determined using Prism SDS software version 1.2 (Applied Biosystems). The level of each gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (23). The Ct value of each gene real-time PCR product was normalized to that for S2 real-time PCR product. The real-time PCR was conducted on three samples of cDNAs in triplicate.

Table 1.

Primer sequences

| Gene | Forward primers | Reverse primers |

|---|---|---|

| Sumo-1 | CCTTTCCAGGACTGTGCATTTT | GGGAAGCTCCCATTAGTCGAT |

| Sumo-2 | GGCAACCAATCAACGAAACAG | TGCTGGAACACATCAATCGTATC |

| Sumo-3 | ACCCAGCCATTTTCCTGACAT | GCGGACTCTTGTGTGATTGGT |

| Senp1 | ACTGCCATGTGTCTGCCTATGA | CCCACTCCAGGACGGACTT |

| Senp2 | GTTGAATGGGAGTGATTGTGGAAT | CTGGTGCTGAGTGAATGTGATAGG |

| Senp3 | GGTCCCTTGTCTCAGTTGATGTAAG | GCGGTTTAGAGTTCGCTGTGA |

| Senp5 | CGAGTGCGGAAGAGGATCTATAAG | AGTCCCTGCTGAGTGAGTGTCA |

| Senp6 | AACGGCACTGTAGCACTTACCA | CTCGAAATGGGTCAGACACTTCT |

| Senp7 | GTCTCAGCCCTCAAATGCAGAT | GAGTAGCAGCCACTGCTTTGTTT |

| Senp8 | TCTTTAGACGACAGCCAGAATCC | ATTCTCCCCTCTTCTTTGTGATGTAT |

| S2 | CTGCTCCTGTGCCCAAGAAG | AAGGTGGCCTTGGCAAAGTT |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis consisted of one-way ANOVA, followed by a pairwise comparison of the means at α = 0.05 (Tukey-Kramer method, JMP; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

SUMO-2 is highly expressed in Sertoli cells, and RARA has four potential SUMO acceptor sites

SUMO-2, expressed from a rat Sertoli cell cDNA library, was identified in our yeast two-hybrid screen as strongly interacting with RARA. Additional yeast two-hybrid screenings with the cells containing the bait or empty bait vectors or with the cells having the bait vector and a plasmid encoding retinoid X receptor-α (RXRA), a known interacting protein of RARA, were performed as controls (data not shown). Sumo-2 cDNA isolated from the LacZ-positive yeast clone was sequenced. The translated protein sequence of Sumo-2 cDNA was 100% identical to SUMO-2 protein sequences derived from mouse (NM_133354), rat (NM_133594), and human (NM_006973) in the GenBank database (Fig. 1A). It contained VKTE, which matched the tetrapeptide sumoylation consensus motif, ψKxD/E (where ψ is a large hydrophobic amino acid and x is any amino acid). SUMO-2/3 is known to covalently attach to the lysine reside within the tetrapeptide sumoylation motif of another SUMO-2/3, making a SUMO-2/3 polychain (10).

Figure 1.

SUMO-2 is highly expressed in Sertoli cells, and RARA has four potential SUMO acceptors. Panel A, The translated protein sequence of Sumo-2 cDNA isolated from a LacZ-positive yeast clone, identified as containing a protein that strongly interacted with RARA. The SUMO-2 sequence was identical to mouse (mSUMO-2), rat (rSUMO-2), and human (hSUMO-2) sequences. The potential sumoylation sites are boxed, and the consensus sequence is indicated. Panel B, Relative expression of each Sumo was determined using real-time RT-PCR in rat Sertoli cells, rat germ cells, and testes from VAD rats. Expression was normalized to the internal control, the ribosomal protein S2 expression. Results are expressed as means ± sem from n = 3 independent RNA samples, with each real-time PCR conducted in triplicate. Different letters denote a significant difference from each other at P < 0.05. Panel C, Four potential sumoylation sites of RARA, K399, K171, K166, and K147, predicted by SUMOplot software, arranged according to predicted score from high to low. Panel D, Schematic of the hRARA, showing amino acid position (Pos.) K399 in the ligand-binding domain (LBD), K166 and K171 in the nuclear localization signal (NLS), and K147 in the DNA-binding domain (DBD). A–F, Modular domains in RARA.

To determine the expression of Sumo-2 in Sertoli and germ cells, relative to other Sumo genes, we conducted real-time RT-PCR for Sumo-1, -2, and -3 on RNA isolated from Sertoli and germ cells and VAD rat testes. The expression level of Sumo-2 transcript was highest when compared with Sumo-1 and -3 transcript levels in Sertoli cells (Fig. 1B). This result was consistent with the distribution of Sumo-1, -2, and -3 expression in VAD rat testes, which have mostly Sertoli cells and very few germ cells. In contrast, the level of Sumo-1 transcript was highest in rat germ cells (Fig. 1B). Thus, the Sumo-2 transcript appears to be an important component of Sertoli cells.

To determine whether any SUMO acceptor sites are present on RARA, the human, mouse, and rat RARA sequence was analyzed by SUMOplot (http://www.abgent. com/doc/sumoplot). Four putative SUMO acceptor sites on RARA were identified: K399 located in the ligand-binding domain with the highest score, the most likely site to accept SUMO; K171 and K166, in the nuclear localization signal with intermediate scores; and K147, in the DNA-binding domain, with the lowest score (Fig. 1, C and D). All tetrapeptide SUMO acceptor sites were highly conserved in RARA from human, mouse, and rat species by sequence alignment (data not shown).

SUMO-2 modification of RARA

To determine whether SUMO-2 modification of RARA occurs in Sertoli cells, primary Sertoli cells were isolated from 20-d-old rats and treated with ATRA and/or FSH, an important gonadotropin for Sertoli cell proliferation. The nuclear extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-RARA antibody or anti-SUMO-2/3 antibody, followed by TCA precipitation (+) to further concentrate immunoprecipitated proteins. In addition, cell extracts from MSC-1 cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-SUMO-2/3 antibody and concentrated by TCA precipitation (+). The TCA concentrated proteins were then subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using anti-RARA antibody. Western blot analyses yielded intense complexes around 150 and 70 kDa, recognized by both anti-RARA and anti-SUMO-2/3 antibodies (Fig. 2A). Because the molecular mass of SUMO is approximately 15 kDa by SDS-PAGE, a covalent attachment of SUMO to 55-kDa RARA could induce a mobility shift, the amount of the upward shift dependent on the number of SUMOs attached to RARA. These results suggest that the endogenous RARA can be conjugated by SUMO-2/3 in primary Sertoli cells and MSC-1 cell line. It should be noted that the efficiency of TCA precipitation was not controlled by spiking with a known marker, and thus, we did not quantitate the bands.

Figure 2.

RARA is covalently modified by SUMO-2 in primary Sertoli cells and MSC-1 and transfected COS-7 cells. A and B, Extracts of primary Sertoli cells (1°SC) or MSC-1 cells, treated with ATRA (1 μm), FSH (25 μm), or ATRA and FSH, as indicated, for 3 h, were loaded onto a column with antibody cross-linked to protein A agarose beads (IP). The eluate was TCA precipitated (+) or not (−), as indicated, and immunoblotted (IB) with anti-RARA antibody or anti-SUMO-2/3 antibody. C and D, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with pFLAG-RARA cDNA and pFLAG-Sumo-2 cDNA constructs, lysed, immunoprecipitated (IP) with either anti-RARA or anti-SUMO-2/3 antibody cross-linked to True Blot antirabbit IP beads, followed by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-SUMO-2/3 or anti-RARA antibody. E, MSC-1 or COS-7 cells were treated with vehicle (−) or ATRA (1 μm) (+) for 24 h, lysed, and subjected to immunoblotting (IB) with anti-RARA antibody. IgG, IgG contaminant in the eluate from the large-scale IP; 150 kDa C and 70 kDa C, protein complexes around 150 and 70 kDa; M, 10% of input, showing RARA or SUMO-2/3. Negative controls included IgG beads incubated with the lysate and no primary antibody (labeled C in C) or BSA loaded on a column packed with anti-RARA antibody cross-linked to protein A agarose beads and immunoblotted (IB) with anti-RARA (labeled BSA in Fig. 2B). Equal loading was determined by the Coomassie-stained membrane (Com.) for E. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

To quantitate the effect of ATRA on SUMO-2 modification of RARA, MSC-1 cells were treated with ATRA (+), cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-RARA antibody, and immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses conducted with anti-RARA or anti-SUMO-2/3 antibody. ATRA treatment of MSC-1 cells significantly enhanced the intensity of ladder-like high molecular mass complexes, recognized by both anti-RARA and anti-SUMO-2/3 antibodies, which included the 150- and 70-kDa complexes (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that ATRA can enhance SUMO-2/3 conjugation of endogenous RARA in MSC-1 cells and, thus, allowing detection of higher molecular mass complexes without TCA precipitation.

Then, to determine whether RARA can be conjugated by SUMO-2 specifically, we took advantage of COS-7 cells, which have little or no endogenous RARA in the absence of ATRA (Fig. 2E). COS-7 cells were transfected with pFLAG-RARA and pFLAG-Sumo-2 cDNA constructs, immunoprecipitated with either anti-RARA or anti-SUMO-2/3 antibody, and then immunoblotted with either anti-SUMO-2/3 (Fig. 2C) or anti-RARA antibody (Fig. 2D). Western blot analyses yielded intense complexes around 150 kDa and a minor band around 70 kDa, indicating that exogenously expressed RARA can be conjugated by SUMO-2.

Mutations of SUMO-2 acceptor lysines on RARA influenced the extent of sumoylation

To determine whether K399 in the ligand-binding domain of RARA could be a SUMO-2 acceptor, K399 was mutated to arginine (K399R) to maintain the net positive charge. Then, COS-7 cells, which have little or no endogenous RARA in the absence of ATRA (Fig. 2E), were cotransfected with pFLAG-RARA or pFLAG-RARA K399R and an increasing amount of pHis-Sumo-2 cDNA constructs. The level of SUMO-2/3 monomer was increased with more pHis-Sumo-2 cDNA transfected into COS-7 cells (Fig. 3A). In addition, it is clear that COS-7 cells have an endogenous level of SUMO-2/3 (Fig. 3A, lane 1), with no pSumo-2 transfected. In the absence of ATRA, sumoylated RARA was detected at a higher concentration of SUMO-2 (Fig. 3B) than was needed to sumoylate RARA in the presence of ATRA (Fig. 3B, lane 1). In contrast, the K399R mutation on RARA totally abrogated the appearance of SUMO-2-conjugated RARA complexes in the absence of ATRA (Fig. 3C). This indicated that K399 was the sole site of sumoylation in the absence of ATRA, albeit at a higher concentration of SUMO-2 than the endogenous concentration of SUMO-2. On the other hand, in the presence of ATRA, the intensity of SUMO-2-conjugated K399R mutant complexes as well as unmodified K399R mutant was enhanced (Fig. 3D) compared with that in the absence of ATRA, indicating that new SUMO acceptor sites are revealed after ATRA treatment, and this may also stabilize the unmodified K399R mutant.

Figure 3.

Mutations of SUMO-2 acceptor lysines on RARA influenced the extent of sumoylation. COS-7 cells were transfected with a varying ratio, as indicated, of pHis-Sumo-2 (pSumo-2) to pFLAG-RARA WT (pRARA) or pFLAG-RARA K399R [pRARA (K399R)] mutant cDNA constructs (A–D) or a set amount of pHis-Sumo-2 (pSumo-2) and pFLAG-RARA WT or various mutants of RARA cDNA constructs, 4:4 ratio (E). Cells were treated with either vehicle or ATRA (1 μm), lysed, and immunoblotted (IB) with anti-RARA antibody (C and D) or anti-SUMO-2/3 (A) or anti-FLAG M2 antibody (B and E). Equal loading was determined by the Coomassie blue dye-stained membranes (Com.). 150 kDa C, protein complexes around 150 kDa. All the experiments were repeated at least three times.

Thus, to ascertain whether K147 in the DNA binding or K166 and K171 in the nuclear localization domains are subject to sumoylation in the presence of ATRA, cDNA constructs were generated to substitute lysine with arginine at these positions and in combination with the K399R mutation. Triple and quadruple mutants (K166/171/399R and K147/166/171/399R) were also generated. COS-7 cells were cotransfected with pHis-Sumo-2 cDNA and either pFLAG-RARA [wild type (WT)] or the different pFLAG-RARA mutant cDNAs and RARA detected with anti-FLAG M2 antibody. The RARA K171/399R and RARA K166/399R (Fig. 3E, lanes 6 and 8) displayed the lowest and next lowest intensities of SUMO-2-conjugated RARA mutant complexes in the presence of ATRA among the double mutants, respectively. Together, these results suggest that K171 and then K166 are sumoylated, in the presence of ATRA, even with K399 mutated to arginine.

K399 sumoylation site is the primary site that influences the RARA subcellular localization

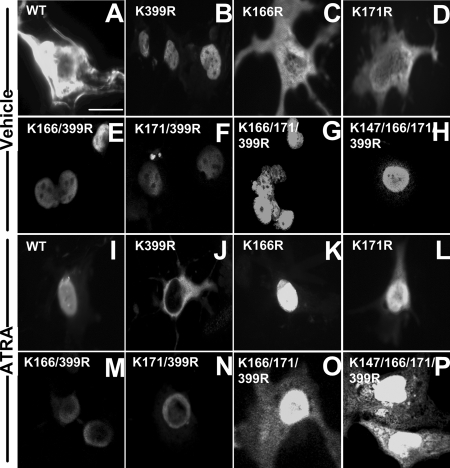

To determine whether mutations at various lysine acceptor sites influence the nuclear localization of the receptor at the endogenous level of SUMO-2 (Fig. 3A, lane 1), COS-7 cells were transfected with pFLAG-RARA WT or various mutant pFLAG-cDNA constructs, treated or not treated with ATRA for 30 min, and then subjected to indirect immunofluorescence assay using anti-FLAG M2 antibody. Surprisingly, totally opposite from the subcellular localization for RARA WT in the absence of ATRA (Fig. 4A), RARA K399R was found in the nucleus in 67% of cells (Fig. 4B). Similarly, in the absence of ATRA, the double, triple, and quadruple mutants of RARA, which all included the mutated K399 site, were primarily found in the nucleus (Fig. 4, E–H). In contrast, RARA K166R and RARA K171R with only a single site mutated had a cytoplasmic localization pattern (Fig. 4, C and D), similar to that observed for RARA WT, in the absence of ATRA (Fig. 4A). These data suggest that a functional K399, which can potentially accept SUMO-2, is essential for maintaining RARA in the cytoplasm in the absence of ATRA.

Figure 4.

K399 sumoylation site was the primary site that influenced the RARA subcellular localization. COS-7 cells were transfected with the pFLAG-RARA WT (A and I) or pFLAG-RARA mutant cDNA constructs (B–D, E–F, J–L, and M–P), treated with either vehicle (A–H) or ATRA (1 μm) (I–P) for 30 min, fixed, and analyzed by immunofluorescence with anti-FLAG M2 antibody. Bar in A, 60 μm for A–P. The images shown represent at least 65% of cells.

More interestingly, in the presence of ATRA, RARA K399R was observed in the cytoplasm in about 75% of cells (Fig. 4J), which was again completely opposite from that of RARA WT (Fig. 4I) and other single mutants of RARA (Fig. 4, K and L). This suggests that sumoylation at K171 and K166 inhibits RARA nuclear localization in the presence of ATRA in K399R mutant. Consistently, the triple and quadruple mutants were primarily observed in the nucleus in the presence of ATRA (Fig. 4, O and P). These results altogether confirm that RARA with K399 mutated to arginine cannot be regulated by ATRA in a manner normally observed for the WT RARA (6).

Triple mutations (K166R/K171R/K399R) enhanced the transcriptional activity of RARA

To determine whether sumoylation has any general suppressive effect on the transcriptional activity of RARA, as previously shown for covalently sumoylated transcription factors such as with c-Jun, c-Myb, and nuclear factor-κB (24,25,26), COS-7 cells were transfected with pFLAG-RARA, pcDNA-Rxra, pcDNA-β-gal, and pRARE- tk-Luc reporter construct along with increasing amounts of pHis-Sumo-2. The highest luciferase activity was detected at the endogenous level of SUMO-2 (0:4 ratio for pSumo-2 to pRARA), whereas the transcriptional activity of RARA declined with increasing SUMO-2 expression (Fig. 5A). To eliminate the possibility that RARE could be recognized by other nuclear receptors such as RARB or RARG (27,28), the same experiment was performed, but cells were treated with Am580, a specific RARA agonist. Similar results were obtained with Am580 (Fig. 5B), indicating that the changes in the luciferase activity were generated by RARA-specific transcription. Therefore, these results demonstrate that overexpressed SUMO-2 can specifically suppress the transcriptional activity of RARA.

Figure 5.

Triple mutations in K166, K171, and K399 enhanced the transcriptional activity of RARA. A and B, COS-7 cells were cotransfected with empty vector or a varying ratio, as indicated, of pHis-Sumo-2 (pSumo-2) to pFLAG-RARA (pRARA) cDNA. C and D, COS-7 cells were cotransfected with pFLAG-RARA WT or mutant RARA cDNA constructs. A–D, pcDNA-Rxra cDNA, pRARE-tk-Luc cDNA and pcDNA-β-gal cDNA constructs were also transfected. Cells were treated with either vehicle (white bars) or ATRA (1 μm) (A, C, and D) (black bars) or Am580 (0.1 μm) (B) (black bars) for 24 h and analyzed by luciferase reporter assay. Results are expressed as means ± sem from n = 3 independent experiments, with each conducted in triplicate. Different letters denote a significant difference from each other at P < 0.05. All the experiments were repeated at least three times.

Then, using the endogenous level of SUMO-2, the effect of SUMO-2 acceptor mutations of RARA on the ATRA-mediated transcriptional activity of RARA was determined. In the presence of ATRA, a K399 mutation of RARA caused a significant decrease in its transcriptional activity compared with that of the WT (Fig. 5C), suggesting that an intact K399 is required for the WT ATRA-dependent transcriptional activity of RARA. The other single mutants, either K166R or K171R mutants, also displayed a significantly reduced level of transcriptional activity compared with that of RARA WT (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that a sumoylation capacity on K166 and K171 is important for the WT transcriptional activity of RARA. In contrast, the transcriptional activity of the double, triple, and quadruple mutants, all with K399 mutated to arginine, was as high as or significantly higher than that of RARA WT (Fig. 5D), consistent with the mutants primarily located in the nucleus.

SENP6 interacts with RARA but not with RARA K399 mutant in primary Sertoli cells

SENP3 is localized predominately in the nucleolus and serves as an enzyme that deconjugates SUMO-2/3 from protein substrates (15), whereas SENP6 with multiple nuclear localization domains and found in both cytoplasm and in the nucleus, is exclusive for deconjugating (editing) SUMO-2/3 from another SUMO-2/3 in a SUMO-2/3 polychain (16). To determine the mRNA expression level of Senp genes, real-time RT-PCR was conducted on RNAs from primary Sertoli cells and germ cells. We found that Senp6 and Senp3, in this order, were highly expressed in rat Sertoli cells (Fig. 6A). In contrast, Senp3 and Senp2 were dominant in germ cells (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

SENP6 interacts with RARA in primary Sertoli cells. A and B, Relative expression of each Senp gene was determined using real-time RT-PCR in rat Sertoli cells (A) and rat germ cells (B). Expression was normalized to the ribosomal protein S2 expression. Results are expressed as means ± sem from n = 3 independent RNA samples, with each conducted in triplicate. Different letters denote a significant difference from each other at P < 0.05. C–H, Primary Sertoli cells were treated with vehicle (C–E) or ATRA (1 μm) (F–H) for 30 min, fixed, and immunostained with anti-RARA (C and F) and anti-SENP6 (D and G) antibodies. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole stained the nucleus. Bar in C, 60 μm for C–H. I and J, Primary Sertoli cells (I) or COS-7 cells (J) transiently transfected with pFLAG-RARAWT cDNA or pFLAG-RARA K399R cDNA constructs were lysed, immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-SENP6 antibody cross-linked to True Blot antigoat IP beads, followed by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-RARA (I) or anti-FLAG M2 (J) antibody. C, a negative control lane showing IgG beads incubated with the lysate and no primary antibody; IgG, IgG contaminant in the eluate from IP; M, 10% of input, showing RARA. All the experiments were repeated at least three times. K, Working model for RARA, SUMO-2, and SENP6 interaction. In the absence of ATRA, sumoylation on K399 may be very low (spiked S) at a physiological concentration of SUMO-2. Binding of ATRA (R) to RARA (rectangle) induces a conformational change to RARA (oval) that reveals K171 and K166 sumoylation sites for SUMO-2 (S) modification. SENP6 (Se6) bound to K399 in the presence of ATRA could desumoylate K171 and K166 before RARA enters the nucleus. CoA, Coactivator; tick marks represent K166, K171, and K399 sites.

Interestingly, SENP6 was found in the cytoplasm in the absence of ATRA (Fig. 6, C–E) and in the nucleus upon ATRA treatment (Fig. 6F–H), indicating that it may accompany RARA into the nucleus and be involved in editing SUMO-2/3 in Sertoli cells. Immunoprecipitation demonstrated that SENP6 binding to RARA in primary Sertoli and COS-7 cells was enhanced with ATRA treatment (Fig. 6, I and J) but not to K399R mutant in COS-7 cells transfected with Rara K399R cDNA (Fig. 6J).

Discussion

Previously, SUMO-1 was found to covalently link to RARA in the presence of ATRA (29); however, the role of SUMO-2/3 in the polysumoylation of RARA has not been investigated. Here, we have identified RARA as a target of SUMO-2 in Sertoli cells. Higher molecular mass RARA complexes (150 and 70 kDa), distinct from the 55-kDa RARA, were detected in primary Sertoli cells and MSC-1 cells by both anti-SUMO-2/3 and anti-RARA antibodies (Fig. 2). The 70-kDa complex could represent one SUMO-2/3 molecule attached to RARA. As for the 150-kDa complex, it likely represents a RARA with multiple SUMO-2/3s attached, although it cannot be ruled out that an additional covalent modification of a yet unidentified character occurred after the first SUMO-2/3 modification. Other intermediate complexes between 70 kDa and 150 kDa may be low and thus, barely detectable. It is possible that a multiple SUMO-2/3 was transferred to RARA en bloc, as has been shown to occur for a multiple SUMO-2/3 attachment to substrates, stimulated by RanBP2 and the PIAS family of E3-like ligases (13,14). Then, intermediate products could represent degradative products and, thus, detectable only if SENP proteases are active. Previously, similar higher molecular mass complexes have been reported for other target proteins (30,31).

Site-directed mutational studies showed that K399 of RARA is the only potential site that can be modified by SUMO-2 at a SUMO-2 level higher than an endogenous concentration of SUMO-2/3 in the absence of ATRA (Fig. 3B). Yet, it is interesting that K399 is a critical, primary site for controlling ATRA-mediated RARA nuclear trafficking. For example, any double mutants, which include the K399R mutation, remained in the same subcellular compartment as the K399R mutant (Fig. 4, E and F), whereas K166R and K171R mutants, without any K399R mutation, followed the nuclear localization pattern observed for the WT RARA (Fig. 4, C and D). Thus, K399 could potentially serve as a sensitive measuring device for detecting the amount of SUMO-2/3 in cells for a regulatory purpose. In this regard, it is relevant to have a means to measure the level of SUMO-2/3 in cells, because there has been a report of hyposumoylation and hypersumoylation in human disease conditions causing azoospermia, hypospermatogenesis, or reduction in spermatogenesis (20).

Further analysis indicated that a functional K399 site is required for docking of SENP6 (Fig. 6K). The interaction with RARA WT was stronger in the presence of ATRA (Fig. 6, I and J). However, regardless of the presence or absence of ATRA stimulation, SENP6 did not interact with RARA K399R (Fig. 6J). High expression of SENP6 expression in Sertoli cells (Fig. 6A) indicates that it could potentially be a candidate for editing and deconjugating SUMO-2/3 from the poly SUMO-2/3 chain on the receptor in the cytoplasm. Indeed, SENP6 was found in the cytoplasm in the absence of ATRA and then translocated into the nucleus with RARA in Sertoli cells, upon ATRA treatment (Fig. 6, F–H). Previously, SENP6 (known as SUSP1 as well) has also been demonstrated to interact and colocalize with RXRA to mediate the transcriptional activity of the RXRA-RARA complex (32).

On the other hand, ATRA is an active inducer of SUMO-2 modification of RARA in Sertoli cells at a physiological concentration of SUMO-2/3. Binding of ATRA to the receptor may induce a major conformational change to the receptor (Fig. 6K), as previously shown (33), which could reveal additional sumoylation sites at K166 and K171. There has been a precedence reported for this type of sumoylation pattern. Sumoylation of androgen receptor at K318 is ligand independent, whereas sumoylation at K511 is ligand dependent (34).

Unexpectedly, however, nuclear localization studies revealed that SUMO-2 modification at K171 and K166 sites after ATRA treatment may be inhibitory to the nuclear localization of the receptor. This is observed in the K399R mutant, which was primarily localized to the cytoplasm (Fig. 4J) in the presence of ATRA. It could be because SENP6 cannot bind to RARA K399R and cannot desumoylate K166 and K171. In agreement, the triple mutant RARA K166/171/399R, which cannot be sumoylated, was primarily found in the nucleus constitutively (Fig. 4, G and O). Another unsumoylated RARA, the K399R mutant, in the absence of ATRA, was also primarily found in the nucleus (Fig. 4B).

At a transcriptional level, RARA K399R had only the basal level, whereas the triple RARA mutant had an even higher level of transcriptional activity than RARA WT (Fig. 5D). In contrast, when K399 is not mutated to arginine, K166 and K171 were required to attain the WT transcriptional activity (Fig. 5C), indicating that sumoylation at these sites is critical for optional transcriptional activity. These results, together with the potential role of SENP6 bound to RARA with intact K399, suggest that a dynamic process of K166 and K171 sumoylation/desumoylation may influence the ATRA-controlled nuclear localization and transcriptional activity of RARA. Manipulation of SUMO-2 sumoylation and desumoylation could be a strategy to control the function of RARA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michael Skinner (Washington State University) for generously providing a Sertoli cell cDNA expression library. We also acknowledge Drs. Steven Collins (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Institute, Seattle, WA), Jan-Ake Gustafsson (Karolinska Institutet, Huddinge, Sweden), and Vincent Giguere (Children’s Hospital, Montreal, Canada) for LRARaSN, rat pRxra, and pRARE-tk-luc, respectively. We are grateful to Drs. Jannette Dufour and Timothy Doyle for critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant HD44569.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online October 22, 2009

Abbreviations: ATRA, All-trans retinoic acid; Ct, cycle threshold; RARA, retinoic acid receptor-α; RARE, retinoic acid-responsive element; RXRA, retinoid X receptor-α; SENP, sentrin-specific peptidase; SUMO-2, small ubiquitin-like modifier-2; TCA, trichloroacetic acid; VAD, vitamin A deficient; WT, wild type.

References

- Lufkin T, Lohnes D, Mark M, Dierich A, Gorry P, Gaub MP, LeMeur M, Chambon P 1993 High postnatal lethality and testis degeneration in retinoic acid receptor α mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:7225–7229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle TJ, Braun KW, McLean DJ, Wright RW, Griswold MD, Kim KH 2007 Potential functions of retinoic acid receptor A in Sertoli cells and germ cells during spermatogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1120:114–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akmal KM, Dufour JM, Kim KH 1997 Retinoic acid receptor α gene expression in the rat testis: potential role during the prophase of meiosis and in the transition from round to elongating spermatids. Biol Reprod 56:549–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour JM, Kim KH 1999 Cellular and subcellular localization of six retinoid receptors in rat testis during postnatal development: identification of potential heterodimeric receptors. Biol Reprod 61:1300–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akmal KM, Dufour JM, Vo M, Higginson S, Kim KH 1998 Ligand-dependent regulation of retinoic acid receptor α in rat testis: in vivo response to depletion and repletion of vitamin A. Endocrinology 139:1239–1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun KW, Tribley WA, Griswold MD, Kim KH 2000 Follicle-stimulating hormone inhibits all-trans-retinoic acid-induced retinoic acid receptor α nuclear localization and transcriptional activation in mouse Sertoli cell lines. J Biol Chem 275:4145–4151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun KW, Vo MN, Kim KH 2002 Positive regulation of retinoic acid receptor α by protein kinase C and mitogen-activated protein kinase in Sertoli cells. Biol Reprod 67:29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard E, Bruck N, Brelivet Y, Bour G, Lalevée S, Bauer A, Poch O, Moras D, Rochette-Egly C 2006 Phosphorylation by PKA potentiates retinoic acid receptor α activity by means of increasing interaction with and phosphorylation by cyclin H/cdk7. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:9548–9553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bour G, Lalevée S, Rochette-Egly C 2007 Protein kinases and the proteasome join in the combinatorial control of transcription by nuclear retinoic acid receptors. Trends Cell Biol 17:302–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay RT 2005 SUMO: a history of modification. Mol Cell 18:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owerbach D, McKay EM, Yeh ET, Gabbay KH, Bohren KM 2005 A proline-90 residue unique to SUMO-4 prevents maturation and sumoylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 337:517–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohren KM, Nadkarni V, Song JH, Gabbay KH, Owerbach D 2004 A M55V polymorphism in a novel SUMO gene (SUMO-4) differentially activates heat shock transcription factors and is associated with susceptibility to type I diabetes mellitus. J Biol Chem 279:27233–27238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertegaal AC 2007 Small ubiquitin-related modifiers in chains. Biochem Soc Trans 35:1422–1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HJ, Tatham MH, Jaffray E, Heath JK, Lam TT, Marshall AG, Hay RT 2005 Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry for the analysis of small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) modification: identification of lysines in RanBP2 and SUMO targeted for modification during the E3 autoSUMOylation reaction. Anal Chem 77:6310–6319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh ET 2009 SUMOylation and de-SUMOylation: wrestling with life’s processes. J Biol Chem 284:8223–8227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay D, Dasso M 2007 Modification in reverse: the SUMO proteases. Trends Biochem Sci 32:286–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Saitoh H, Matunis MJ 2002 Enzymes of the SUMO modification pathway localize to filaments of the nuclear pore complex. Mol Cell Biol 22:6498–6508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Salle S, Sun F, Zhang XD, Matunis MJ, Handel MA 2008 Developmental control of sumoylation pathway proteins in mouse male germ cells. Dev Biol 321:227–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigodner M, Morris PL 2005 Testicular expression of small ubiquitin-related modifier-1 (SUMO-1) supports multiple roles in spermatogenesis: silencing of sex chromosomes in spermatocytes, spermatid microtubule nucleation, and nuclear reshaping. Dev Biol 282:480–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PW, Hwang K, Schlegel PN, Morris PL 2008 Small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO)-1, SUMO-2/3 and SUMOylation are involved with centromeric heterochromatin of chromosomes 9 and 1 and proteins of the synaptonemal complex during meiosis in men. Hum Reprod 23:2850–2857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SJ, Robertson KA, Mueller L 1990 Retinoic acid-induced granulocytic differentiation of HL-60 myeloid leukemia cells is mediated directly through the retinoic acid receptor (RAR-α). Mol Cell Biol 10:2154–2163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Kim KH 1993 Vitamin A-deficient testis germ cells are arrested at the end of S phase of the cell cycle: a molecular study of the origin of synchronous spermatogenesis in regenerated seminiferous tubules. Biol Reprod 48:1157–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD 2001 Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller S, Berger M, Lehembre F, Seeler JS, Haupt Y, Dejean A 2000 c-Jun and p53 activity is modulated by SUMO-1 modification. J Biol Chem 275:13321–13329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bies J, Markus J, Wolff L 2002 Covalent attachment of the SUMO-1 protein to the negative regulatory domain of the c-Myb transcription factor modifies its stability and transactivation capacity. J Biol Chem 277:8999–9009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D, Müller S 2002 Members of the PIAS family act as SUMO ligases for c-Jun and p53 and repress p53 activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:2872–2877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli JL 1996 Retinoic acid biosynthesis and metabolism. FASEB J 10:993–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambon P 1996 A decade of molecular biology of retinoic acid receptors. FASEB J 10:940–954 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Lin XF, Ye XF, Zhang B, Xie Z, Su WJ 2004 Ubiquitinated or sumoylated retinoic acid receptor α determines its characteristic and interacting model with retinoid X receptor α in gastric and breast cancer cells. J Mol Endocrinol 32:595–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo WZ, Sugaya S, Satoh M, Tomonaga T, Nomura F, Hiwasa T, Takiguchi M, Kita K, Suzuki N 2009 Nm23–H1 is responsible for SUMO-2-involved DNA synthesis induction after x-ray irradiation in human cells. Arch Biochem Biophys 486:81–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisshaar SR, Keusekotten K, Krause A, Horst C, Springer HM, Göttsche K, Dohmen RJ, Praefcke GJ 2008 Arsenic trioxide stimulates SUMO-2/3 modification leading to RNF4-dependent proteolytic targeting of PML. FEBS Lett 582:3174–3178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SJ, Chung SS, Rho EJ, Lee HW, Lee MH, Choi HS, Seol JH, Baek SH, Bang OS, Chung CH 2006 Negative modulation of RXRα transcriptional activity by small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) modification and its reversal by SUMO-specific protease SUSP1. J Biol Chem 281:30669–30677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien J, Rochette-Egly C 2004 Nuclear retinoid receptors and the transcription of retinoid-target genes. Gene 328:1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callewaert L, Verrijdt G, Haelens A, Claessens F 2004 Differential effect of small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO)-ylation of the androgen receptor in the control of cooperativity on selective versus canonical response elements. Mol Endocrinol 18:1438–1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]