ABSTRACT

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer with approximately half of the patients developing liver metastases during the course of their disease. Modern multimodal therapies have improved the overall survival. Liver resection remains the most important modality in the treatment of colorectal liver metastases. The evolution of the criteria for resectability has resulted in more patients being offered a hepatectomy. This is further augmented with the utilization of adjuncts to liver resection, including portal vein embolization and local ablative techniques. Two-stage hepatectomy is also being used to increase resectability. Overall survival is improved by the deployment of new chemotherapeutic agents and the use of combination chemotherapy. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is a promising development in the treatment of colorectal liver metastases. Patients with colorectal liver metastases can achieve long-term survival. A multidisciplinary approach is essential in the management of these patients.

Keywords: Liver, colorectal liver metastases, hepatectomy, chemotherapy

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer. There are one million new cases of colorectal cancer annually in both males and females worldwide.1 Approximately 50% of patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer will develop liver metastases over the course of their disease.2

OUTCOMES

The natural history of untreated colorectal liver metastases is well documented. Outcomes for untreated disease are dismal. The median survival is in the order of 6 to 9 months. The 5-year survival ranges between 0 to 3%.3,4,5

Outcomes are improved with resection. Surgery alone does offer a cure in a subset of patients.6 The use of chemotherapy as an adjunct to liver resection has resulted in a 5-year survival in the range of 37 to 58%.7,8,9 Ten-year survival is reported to be between 16 to 30%.8,10,11

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS AND CLINICAL RISK SCORES

Several prognostic factors have been reported to be associated with worse outcomes. Extrahepatic disease, extrahepatic lymph node involvement, satellite configuration of multiple metastases and initial detection of abnormal liver enzymes were originally reported to be predictors of worse survival.12 Later, Nordlinger et al proposed a clinical risk score that divided patients into three risk groups.13 They found age, size of the largest primary, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level, stage of the primary tumor, disease-free interval, number of liver nodules, and resection margins to impact 5-year survival. More recently, Fong et al7 proposed a clinical risk score, which is shown in Table 1. It is important to note that clinical risk scores are prognostic tools and they should not be used to deny patients a surgical resection.

Table 1.

Clinical Risk Score

| Nodal status of the primary disease-free interval from the discovery of the primary to the discovery of the liver metastases of <12 months |

| Number of tumors >1 |

| Preoperative CEA level of >200 ng/mL |

| Size of the largest tumors >5 cm |

Each positive criterion is assigned one point. 5-year survival is 60% with score of 0 points, and falls to 14% in patients with 5 points. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

IMAGING COLORECTAL LIVER METASTASES

Imaging plays a key role in patient evaluation and in preoperative selection. The modalities currently available for patient assessment include ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET), and integrated PET-CT.

Abdominal US is a noninvasive, low-cost, and readily available modality for diagnosing colorectal liver metastases. However, it is operator dependent and the sensitivity may be related to the patient's body habitus. The use of duplex US can define lesion(s) proximity to the vascular structures. Contrast US is a new technique, which is still not widely adopted, but shows some promise.

Currently, CT is the preferred modality in the assessment of colorectal liver metastases. The detection rate of hepatic metastases varies between 68 to 91% (70% detection for lesions >1 cm). However, the sensitivity and specificity of CT of the liver will vary with the equipment and the contrast enhancement techniques used.14

In patients with iodinated contrast sensitivity or severe fatty steatosis, gadolinium-enhanced MRI is the best diagnostic alternative. Most comparative studies have shown that MR imaging is not superior to CT in the evaluation of colorectal liver metastases. MRI can be useful in detection and characterization of small liver metastases, especially in distinguishing small metastases from small cysts.15

A recent meta-analysis revealed that FDG PET had significantly higher sensitivity on a per patient basis, compared with CT and MRI.16 In a study by Ruers et al, the use of PET as a complementary staging method altered the management radically in 20% of patients.17 It is important to note that exact localization and demarcation of lesions with PET is hindered by its relatively low spatial resolution and lack of anatomic reference.18 The fusion of PET (accurate tumor detection) and CT (anatomic reference) as PET-CT has provided the theoretical benefit of both. The final role of PET in the evaluation of patients with colorectal liver metastasis is yet to be defined.

INTRAOPERATIVE ULTRASOUND

Intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) has proven to be a valuable tool in the evaluation of patients with colorectal liver metastases. IOUS has a sensitivity of 98% and can detect lesions as small as 5 mm.19 Modification of surgical management secondary to the use of IOUS is reported to be between 17 to 44%.20,21,22 This is even seen in patients who had a preoperative PET-CT evaluation. The routine use of IOUS in all patients undergoing hepatectomy for metastatic colorectal cancer is now considered the standard of care.

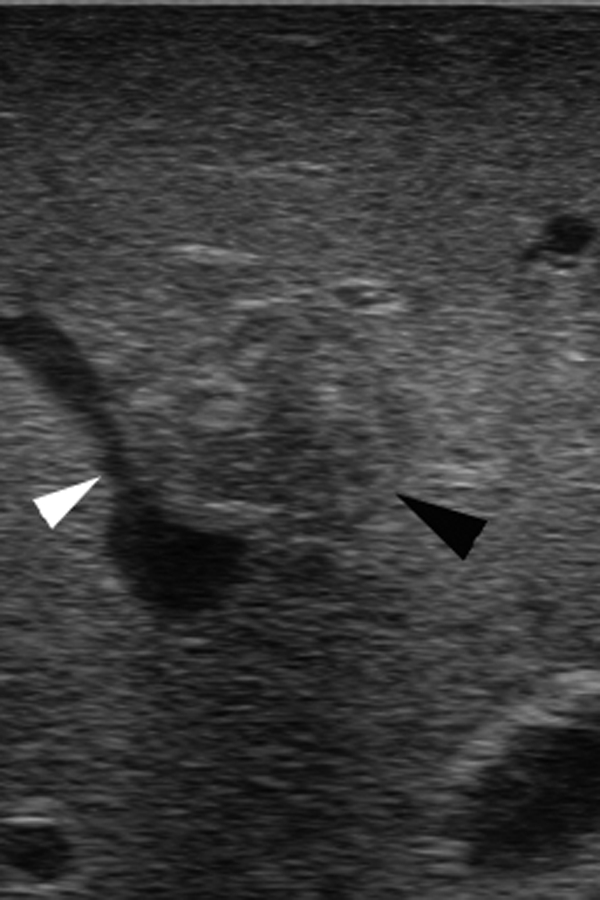

In addition to detection of metastases, IOUS can identify anatomy and vascular structures leading the way to a safer and more precise liver resection (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Intraoperative ultrasound scan shows the proximity of a colorectal metastasis (black arrowhead) to the middle hepatic vein (white arrowhead).

LAPAROSCOPIC STAGING IN COLORECTAL LIVER METASTASES

Proper selection of surgical candidates is mandatory to optimize benefits and minimize risks. Laparoscopic staging has been used to help with patient selection; however, there is no clear consensus in the literature about its use. In a study, which evaluated diagnostic laparoscopy and laparoscopic ultrasound, factors precluding curative resection were identified in 21% of patients.23 This averted unnecessary laparotomy in those patients, but at a cost of 4% adverse events. In a larger review,24 where 199 patients with colorectal liver metastases were evaluated, the yield of laparoscopy for unresectability was 10%. Mortensen et al25 reported a similar outcome. In their series, only 9% of patients were identified as unresectable secondary to use of laparoscopy and laparoscopic ultrasound. Therefore, the routine use of diagnostic laparoscopy or laparoscopic ultrasound remains unwarranted.

RESECTABILITY OF COLORECTAL LIVER METASTASES

Surgery remains the gold standard in the treatment of colorectal liver metastases. All patients should be assessed for a resection.

The criteria for resectability have evolved over time. In 1986, Ekberg et al defined resectability as less than four metastases (even if bilobar), absence of extrahepatic disease, and a resection margin of at least 1 cm. They recommended that resection should not be performed unless all these criteria are met.26 Others have followed their footsteps. Recommendations for best outcomes include resection of metastases only from colorectal primary, absence of comorbidities, absence of extrahepatic disease, three or less metastases, and complete resections (i.e., margin free).2 Later, unresectability was defined in relation to size of tumor, poor location, multinodularity, and extrahepatic disease.27 The criteria were then further liberalized. Figueras et al28 reported on expanded criteria based only on complete and macroscopically curative resection.

Currently, a paradigm shift is taking place in the definition of resectability of colorectal liver metastases. Previously, patients had to meet specific inclusion criteria to be considered resectable. Today, resections are based on the remnant liver. A sufficient future remnant liver volume (>20% of the total estimated liver volume) is a prerequisite. This is in addition to maintaining vascular inflow and outflow, as well as biliary drainage. The resection should lead to a macroscopic and microscopic treatment of the disease.29

As such contraindications to liver resection would include uncontrollable extrahepatic disease such as nontreatable primary tumor, widespread pulmonary disease, peritoneal disease, extensive nodal disease, such as retroperitoneal or mediastinal nodes and bone or central nervous system (CNS) metastases.14

TECHNIQUES TO INCREASE RESECTABILITY IN COLORECTAL LIVER METASTASES

Several techniques are used to improve resectability in patients who fail to meet resection criteria. These include portal vein occlusion, local ablation techniques, and two-stage hepatectomy. The use of downstaging chemotherapy will be discussed separately. These techniques can be used in isolation, but are more effective when considered in a multimodality approach.

Portal Vein Occlusion

Portal vein occlusion can be achieved by means of portal vein embolization (PVE) or ligation. The goal is to produce atrophy of the affected lobe and hypertrophy of the contralateral side, thus increasing the size of the future remnant liver volume (FRLV). A 20% FRLV is required for patients with normal underlying liver. In the presence of liver injury secondary to steatosis or steatohepatitis, 30% FRLV is required. In cirrhotic livers, 40% FRLV is the minimum requirement.

The mechanism of hypertrophy is related to hemodynamic changes following PVE. A variety of conditions have been shown to inhibit regeneration. These include biliary obstruction, diabetes, chronic ethanol consumption, malnutrition, gender, aging, and infection.30

Local Ablation Techniques

Different techniques for local ablation have been developed in recent years. Combining local ablation to hepatic resection has increased resectability. Thermal techniques using radiofrequency ablation (RFA) are the most commonly used methods. Other thermal ablative techniques include cryotherapy, laser interstitial thermotherapy, microwave coagulation therapy, hot saline injection, and high-intensity focused ultrasound.

In RFA, an alternating current (460 kHz) is applied via electrode(s) implanted into the center of the metastases under ultrasound guidance. The current raises the temperature within the cells. This leads to cell destruction and the formation of a zone of coagulative necrosis around the electrode. RFA can be applied percutaneously, laparoscopically, or during open surgery.

RFA should be restricted to tumors less then 5 cm in diameter, and preferably to lesions smaller than 3 cm in diameter.31

In a retrospective report of 117 patients with 179 metachronous metastases, local recurrence developed in 39% of the treated lesions and was related to lesion size.32 Local recurrence rates for lesions of diameter ≤2.5, 2.6 to 4.0, or ≥4.1 cm were 22, 53, and 68%, respectively.

Two-Stage Hepatectomy

In a subset of patients, complete resection cannot be achieved even after the use of downstaging chemotherapy, PVE, and/or local ablation techniques. In this group of patients, complete resection may be achievable with a two-stage hepatectomy.

The procedure is performed with an overall curative intent. The initial stage of the hepatic resection is intended to remove the highest possible number of metastases. The remnant liver hypertrophies and systemic chemotherapy limits the growth and spread of the remaining tumor deposits. The second hepatectomy is performed if it is potentially curative, in the absence of significant tumor progression, and when adequate parenchymal hypertrophy has reduced the risk of postoperative liver failure.27,33

SYNCHRONOUS METASTASES AND TIMING OF RESECTION

Synchronous metastases are defined as metastases that present within a year of the primary tumor. The timing of hepatic resections in patients with synchronous colorectal liver metastases remains controversial. However, there is increasing support in recent literature for simultaneous resections.

Chau et al34 reported their experience at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN). In a retrospective review of 96 patients, 64 patients underwent a simultaneous resection. The remaining 32 patients had staged colonic and hepatic resections. No significant differences were observed between the two groups. The study concluded that simultaneous colectomy and hepatectomy is safe and more efficient than staged resection, and should be the procedure of choice where the expertise is available.

This finding was similar to the experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (New York, NY).35 Two-hundred forty patients were treated surgically for colon cancer and synchronous hepatic metastases. Of those, 134 patients underwent simultaneous colectomy and hepatectomy. Perioperative mortality was found to be similar and overall complications were less in the simultaneous resection group. This was achieved by avoiding a second laparotomy. In this study, simultaneous resections were deemed to be safe and efficient.

The need for a major hepatectomy (involving three or more segments36,37) used to be a contraindication for a simultaneous resection. However, this concept has been challenged recently.38 Short-term outcomes for simultaneous resection involving a major hepatectomy are similar to the outcomes of patients with two-stage resections.

It is important to note that certain clinical presentations may dictate the approach to synchronous disease. Patients who present with obstruction, perforation, and bleeding should receive immediate surgical attention to the primary tumor.39

REPEAT RESECTIONS

Of all patients who undergo a hepatic resection for colorectal metastases, 60% will have recurrent disease. Off those, a third will have liver-only recurrence. With the improvements in surgical technique, perioperative management, and the overall decreasing morbidity and mortality associated with liver resections, repeat hepatectomy is the treatment of choice for resectable disease. Repeat resections are technically more challenging. This is due to the formation of perihepatic adhesions, altered anatomy of the remnant liver due to regeneration, and fragile liver parenchyma associated with chemotherapy treatment.

The perioperative complication rates and mortality are comparable to those after first resection.40 Repeat resection is associated with survival benefits similar to that of the first hepatectomy.40,41,42 These findings can also be extended to the third hepatectomy.43 Predictors of worse survival include size of largest tumor >5 cm, CEA level >30 ng/mL, positive surgical margin, presence of extrahepatic disease, number of tumors at repeat resection >3, positive regional lymph nodes at repeat resection, and an interval <1 year between first and repeat resection.43,44,45

The frequency of repeat hepatectomy has been increasing. Adam et al43 reported an increase in the repeat hepatectomy rate from 15% of overall hepatectomies in the period from 1984 to1990, to 37% of all hepatectomies in the period from 1996 to 2000.

RESECTION MARGINS

Resections of colorectal liver metastases must be approached with “intent to cure.” A margin negative resection is known to positively impact the local recurrence rate and long-term survival.7,13 Improved outcomes in terms of local recurrence and survival have been associated with a minimum of 1-cm margin.46,47 This led to the adoption of the traditional 1-cm margin policy at many centers. However, curative hepatectomies have been reported with margins <1 cm.48,49

More recently, a microscopically positive resection margin (R1 resection) by necessity was not found to impact 5-year overall survival. However, patients with R1 resections had higher recurrence rates.50

LAPAROSCOPIC LIVER RESECTION FOR COLORECTAL LIVER METASTASES

The first successful anatomic hepatectomy was reported in 1996 by Azagra et al,51 who performed a left lateral segmentectomy for a benign adenoma. Retrospective reviews of laparoscopic liver resection, including subsets of patients with colorectal liver metastases have shown oncologic equivalency to open resections. In contrast to laparoscopic colon surgery for cancer, no randomized controlled trial has evaluated laparoscopic liver resection for colorectal liver metastases.

Most of the published literature report on small series at single institutions. Buell et al52 reported on their experience with laparoscopic liver procedures. Their series included 31 patients who underwent a laparoscopic hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases. All of the resected patients had negative margins. Mala et al53 reported on 42 patients with colorectal liver metastases. Their margin positive rate was comparable to that of open technique. The complication rate in both series was comparable to the open approach.

These series agreed on tumor clearance, feasibility, and short-term safety of laparoscopic liver resection. Long-term outcomes are being reported. In one series54 with totally laparoscopic liver resection, the overall 5-year survival rate was 64%. This is comparable to outcomes with open surgery.

SYSTEMIC THERAPY FOR COLORECTAL LIVER METASTASES

In the last few years, we have seen unprecedented advances in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is now not the only active agent in the treatment of colorectal liver metastases. Newer agents such as irinotecan, oxaliplatin, cetuximab, panitumumab, and bevacizumab are now widely used.

The goals of chemotherapy treatment are dictated by the clinical scenario of a particular patient.

Nonresectable Disease

In this subset of patients, chemotherapy is given as a palliative treatment. It has been shown to be effective in prolonging time to disease progression and survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.55

Potentially Resectable Disease

This subset of patients requires downstaging chemotherapy (possibly with the addition of other techniques), to render the disease resectable. Chemotherapy is given in a neoadjuvant fashion to serve as a conversion therapy. The number of patients who eventually achieve complete resection varies from 3.3 to 41%.11,56,57

Adam et al11 presented a review of 1104 initially unresectable patients with colorectal liver metastases who were treated by chemotherapy. The chemotherapeutic regimens consisted of 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin combined with oxaliplatin in 70% of the patients, irinotecan in 7%, or both in 4%. One hundred thirty-eight patients (12.5%) underwent hepatic resection after an average of 10 courses of chemotherapy. The survival rate of primarily resectable versus primarily unresectable metastases downstaged by chemotherapy at 5 and 10 years was 48% versus 33% and 30% versus 23%, respectively.

Resectable Disease

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy has its advantages, but it also comes with some risks. Decreases in tumor size, control of micrometastatic disease, assessment of activity of chemotherapy, better chemotherapy tolerance, and acting as a surrogate marker for success of liver surgery are reported benefits.58 On the other hand, disadvantages of this approach include liver toxicity, progression while on treatment, and the possibility of complete radiologic response, which may make intraoperative localization difficult.58

The EORTC (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer) Intergroup trial 4098359 is a prospective trial that looked at the perioperative chemotherapy for initially resectable disease. This included patients who were initially resectable with ≤four metastases and no extrahepatic disease. One hundred eighty-two patients were randomized to perioperative chemotherapy and the same number were randomized to surgery alone. The chemotherapy regime consisted of six cycles of FOLFOX (oxaliplatin, 5-flourouracil, and leucovorin) before surgery and six cycles after surgery. When resected patients were analyzed, there was a significant 9.2% increase in the progression-free survival rate at 3 years favoring the perioperative chemotherapy group. The overall survival rate was not reported.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for primarily resectable colorectal liver metastases remains controversial. No guidelines currently exist to help with this decision. However, this area is being actively investigated.

COMPLETE RESPONSE

With the advent of modern chemotherapy, a subset of patients will have a complete radiologic response. This is defined as the disappearance of target lesions on imaging. Complete response has important implications. In a single institution study,60 586 patients treated for colorectal liver metastases were evaluated for complete response postchemotherapy. Sixty-six sites in 38 patients were identified. The study concluded that a cure was not achieved in 55 sites with complete radiologic response (83%).

In patients with complete pathologic response (CPR), outcomes are exceedingly favorable. A review61 of 767 consecutive patients operated on for colorectal liver identified 29 patients (4%) with CPR. Interestingly, none of the 29 patients had a complete clinical response. The overall 5-year survival in the group of CPR was 76% versus 45% for patients without CPR. Predictors of CPR were age ≤60 years, with metastases ≤3 cm, CEA level at diagnosis ≤30 ng/mL, and objective response following chemotherapy.

STAGING SYSTEM

Patients with colorectal liver metastases are all considered stage IV disease according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer Cancer Staging Manual, 6th edition, 2002, Springer-Verlag. However, the long-term outcomes and survival for this group is clearly variable. A group of experts have called for a new staging system in advanced colorectal cancer.62 The current staging system has not kept pace with significant clinical advances. For example, resectable colorectal liver metastases with a curative intent is associated with a 5-year survival rate of ~40%, in contrast to unresectable disease where the 5-year survival rate is less than 5%. The proposed new staging system is a substaging of stage IV disease. According to the authors, this will provide better stratification of patients and a more meaningful cross- trial comparison between patients.

FOLLOW-UP AFTER LIVER RESECTION

Currently, there is no consensus in the literature for follow-up after surgical resection for colorectal liver metastases. Most centers continue to follow-up patients for 5 years using their own protocol. A review63 examined outcomes related to mode of surveillance post hepatectomy. It could not uncover direct evidence supporting any particular surveillance modality. They recommended visits every 3 months for 2 years and then every 6 months for 5 years. Each visit was proposed to include clinical evaluation, CEA level measurement, and CT of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis.

A 10-year follow-up study by Vigano et al reported that 98% of all recurrences occurred before the first 5 years of follow-up, but 15% of patients who were disease-free at 5 years later developed recurrence.10

Another study64 evaluated actual 10-year survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases in an attempt to define cure. Of the 612 patients identified with a potential 10-year follow-up, 102 patients were actual 10-year survivors; 97% of those patients were disease-free at that mark. Only one patient experienced a disease-specific death after 10 years of survival. Patients who survive 10 years appear to be cured from their disease, as opposed to approximately one-third of the 5-year survivors who succumb to a cancer-related death.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH TO COLORECTAL LIVER METASTASES

Care for patients with colorectal liver metastases is fairly complex. Patient treatment should be discussed by a multidisciplinary tumor board,14 consisting of surgeons, medical oncologists, radiologists, and other key members. This will ensure that all possible treatment modalities, and the order in which they are implemented, have been fully considered.

CONCLUSION

The management of colorectal liver metastases has evolved over the past few years. More patients are now offered surgery. The use of adjunct techniques to surgery has increased resectability rates. Modern chemotherapeutic agents have significantly improved outcomes. Long-term cure is a realistic goal for a subset of patients with this disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parkin D M, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(2):74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steele G, Jr, Ravikumar T S. Resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Biologic perspective. Ann Surg. 1989;210(2):127–138. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198908000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheele J, Stangl R, Altendorf-Hofmann A. Hepatic metastases from colorectal carcinoma: impact of surgical resection on the natural history. Br J Surg. 1990;77(11):1241–1246. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800771115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rougier P, Milan C, Lazorthes F, et al. Prospective study of prognostic factors in patients with unresected hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Fondation Française de Cancérologie Digestive. Br J Surg. 1995;82(10):1397–1400. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800821034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pestana C, Reitemeier R J, Moertel C G, Judd E S, Dockerty M B. The natural history of carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Am J Surg. 1964;108:826–829. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(64)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordlinger B, Quilichini M A, Parc R, Hannoun L, Delva E, Huguet C. Hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases. Influence on survival of preoperative factors and surgery for recurrences in 80 patients. Ann Surg. 1987;205(3):256–263. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198703000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun R L, Brennan M F, Blumgart L H. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230(3):309–318. discussion 318–321. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choti M A, Sitzmann J V, Tiburi M F, et al. Trends in long-term survival following liver resection for hepatic colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2002;235(6):759–766. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200206000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdalla E K, Vauthey J N, Ellis L M, et al. Recurrence and outcomes following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection/ablation for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2004;239(6):818–825. discussion 825–827. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000128305.90650.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viganò L, Ferrero A, Lo Tesoriere R, Capussotti L. Liver surgery for colorectal metastases: results after 10 years of follow-up. Long-term survivors, late recurrences, and prognostic role of morbidity. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(9):2458–2464. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9935-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adam R, Delvart V, Pascal G, et al. Rescue surgery for unresectable colorectal liver metastases downstaged by chemotherapy: a model to predict long-term survival. Ann Surg. 2004;240(4):644–657. discussion 657–648. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000141198.92114.f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosen C B, Nagorney D M, Taswell H F, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion and determinants of survival after liver resection for metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1992;216(4):493–504. discussion 504–505. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199210000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nordlinger B, Guiguet M, Vaillant J C, et al. Association Française de Chirurgie Surgical resection of colorectal carcinoma metastases to the liver. A prognostic scoring system to improve case selection, based on 1568 patients. Cancer. 1996;77(7):1254–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garden O J, Rees M, Poston G J, et al. Guidelines for resection of colorectal cancer liver metastases. Gut. 2006;55(Suppl 3):iii1–iii8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.098053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martínez L, Puig I, Valls C. Colorectal liver metastases: Radiological diagnosis and staging. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33(Suppl 2):S5–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bipat S, Leeuwen M S van, Comans E F, et al. Colorectal liver metastases: CT, MR imaging, and PET for diagnosis—meta-analysis. Radiology. 2005;237(1):123–131. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2371042060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruers T J, Langenhoff B S, Neeleman N, et al. Value of positron emission tomography with [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose in patients with colorectal liver metastases: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(2):388–395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogel W V, Wiering B, Corstens F H, Ruers T JM, Oyen W JG. Colorectal cancer: the role of PET/CT in recurrence. Cancer Imaging. 2005;5(Spec No A):S143–S149. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2005.0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charnley R M, Morris D L, Dennison A R, Amar S S, Hardcastle J D. Detection of colorectal liver metastases using intraoperative ultrasonography. Br J Surg. 1991;78(1):45–48. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazzoni G, Napoli A, Mandetta S, et al. Intra-operative ultrasound for detection of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Liver Int. 2008;28(1):88–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cervone A, Sardi A, Conaway G L. Intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) is essential in the management of metastatic colorectal liver lesions. Am Surg. 2000;66(7):611–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wildi S M, Gubler C, Hany T, et al. Intraoperative sonography in patients with colorectal cancer and resectable liver metastases on preoperative FDG-PET-CT. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;36(1):20–26. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pilkington S A, Rees M, Peppercorn D, John T G. Laparoscopic staging in selected patients with colorectal liver metastases as a prelude to liver resection. HPB (Oxford) 2007;9(1):58–63. doi: 10.1080/13651820601150986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grobmyer S R, Fong Y, D'Angelica M, Dematteo R P, Blumgart L H, Jarnagin W R. Diagnostic laparoscopy prior to planned hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Arch Surg. 2004;139(12):1326–1330. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.12.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mortensen F V, Zogovic S, Nabipour M, et al. Diagnostic laparoscopy and ultrasonography for colorectal liver metastases. Scand J Surg. 2006;95(3):172–175. doi: 10.1177/145749690609500308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ekberg H, Tranberg K G, Andersson R, et al. Determinants of survival in liver resection for colorectal secondaries. Br J Surg. 1986;73(9):727–731. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800730917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bismuth H, Adam R, Levi F, et al. Resection of nonresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 1996;224(4):509–520. discussion 520–522. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199610000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Figueras J, Torras J, Valls C, et al. Surgical resection of colorectal liver metastases in patients with expanded indications: a single-center experience with 501 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(4):478–488. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pawlik T M, Choti M A. Surgical therapy for colorectal metastases to the liver. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11(8):1057–1077. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokoyama Y, Nagino M, Nimura Y. Mechanisms of hepatic regeneration following portal vein embolization and partial hepatectomy: a review. World J Surg. 2007;31(2):367–374. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0526-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rhim H, Dodd G D., III Radiofrequency thermal ablation of liver tumors. J Clin Ultrasound. 1999;27(5):221–229. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0096(199906)27:5<221::aid-jcu1>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solbiati L, Livraghi T, Goldberg S N, et al. Percutaneous radio-frequency ablation of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: long-term results in 117 patients. Radiology. 2001;221(1):159–166. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2211001624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adam R, Laurent A, Azoulay D, Castaing D, Bismuth H. Two-stage hepatectomy: a planned strategy to treat irresectable liver tumors. Ann Surg. 2000;232(6):777–785. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200012000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chua H K, Sondenaa K, Tsiotos G G, Larson D R, Wolff B G, Nagorney D M. Concurrent vs. staged colectomy and hepatectomy for primary colorectal cancer with synchronous hepatic metastases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(8):1310–1316. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0586-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin R, Paty P, Fong Y, et al. Simultaneous liver and colorectal resections are safe for synchronous colorectal liver metastasis. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197(2):233–241. discussion 241–242. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00390-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adam R, Bismuth H, Castaing D, et al. Repeat hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 1997;225(1):51–60. discussion 60–62. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199701000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petrowsky H, Gonen M, Jarnagin W, et al. Second liver resections are safe and effective treatment for recurrent hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: a bi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg. 2002;235(6):863–871. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200206000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Capussotti L, Ferrero A, Viganò L, Ribero D, Lo Tesoriere R, Polastri R. Major liver resections synchronous with colorectal surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(1):195–201. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adam R. Colorectal cancer with synchronous liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2007;94(2):129–131. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antoniou A, Lovegrove R E, Tilney H S, et al. Meta-analysis of clinical outcome after first and second liver resection for colorectal metastases. Surgery. 2007;141(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sa Cunha A, Laurent C, Rault A, Couderc P, Rullier E, Saric J. A second liver resection due to recurrent colorectal liver metastases. Arch Surg. 2007;142(12):1144–1149. discussion 1150. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.12.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaw I M, Rees M, Welsh F K, Bygrave S, John T G. Repeat hepatic resection for recurrent colorectal liver metastases is associated with favourable long-term survival. Br J Surg. 2006;93(4):457–464. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adam R, Pascal G, Azoulay D, et al. Liver resection for colorectal metastases: the third hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 2003;238(6):871–883. discussion 883–884. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000098112.04758.4e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nishio H, Hamady Z Z, Malik H Z, et al. Outcome following repeat liver resection for colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33(6):729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamamoto J, Kosuge T, Shimada K, Yamasaki S, Moriya Y, Sugihara K. Repeat liver resection for recurrent colorectal liver metastases. Am J Surg. 1999;178(4):275–281. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cady B, Jenkins R L, Steele G D, Jr, et al. Surgical margin in hepatic resection for colorectal metastasis: a critical and improvable determinant of outcome. Ann Surg. 1998;227(4):566–571. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199804000-00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scheele J, Stang R, Altendorf-Hofmann A, Paul M. Resection of colorectal liver metastases. World J Surg. 1995;19(1):59–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00316981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elias D, Cavalcanti A, Sabourin J C, Pignon J P, Ducreux M, Lasser P. Results of 136 curative hepatectomies with a safety margin of less than 10 mm for colorectal metastases. J Surg Oncol. 1998;69(2):88–93. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199810)69:2<88::aid-jso8>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Konopke R, Kersting S, Makowiec F, et al. Resection of colorectal liver metastases: is a resection margin of 3 mm enough?: a multicenter analysis of the GAST Study Group. World J Surg. 2008;32(9):2047–2056. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9629-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Haas R J, Wicherts D A, Flores E, Azoulay D, Castaing D, Adam R. R1 resection by necessity for colorectal liver metastases: is it still a contraindication to surgery? Ann Surg. 2008;248(4):626–637. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818a07f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Azagra J S, Goergen M, Gilbart E, Jacobs D. Laparoscopic anatomical (hepatic) left lateral segmentectomy-technical aspects. Surg Endosc. 1996;10(7):758–761. doi: 10.1007/BF00193052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buell J F, Thomas M T, Rudich S, et al. Experience with more than 500 minimally invasive hepatic procedures. Ann Surg. 2008;248(3):475–486. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318185e647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mala T, Edwin B, Rosseland A R, Gladhaug I, Fosse E, Mathisen O. Laparoscopic liver resection: experience of 53 procedures at a single center. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12(4):298–303. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-0974-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sasaki A, Nitta H, Otsuka K, Takahara T, Nishizuka S, Wakabayashi G. Ten-year experience of totally laparoscopic liver resection in a single institution. Br J Surg. 2009;96(3):274–279. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simmonds P C, Colorectal Cancer Collaborative Group Palliative chemotherapy for advanced colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2000;321(7260):531–535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7260.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Delaunoit T, Alberts S R, Sargent D J, et al. Chemotherapy permits resection of metastatic colorectal cancer: experience from Intergroup N9741. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(3):425–429. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De La Camara J, Rodriguez J, Rotellar F, et al. Triplet therapy with oxaliplatin, irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid within a combined modality approach in patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14S):3593. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kemeny N. Presurgical chemotherapy in patients being considered for liver resection. Oncologist. 2007;12(7):825–839. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-7-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nordlinger B, Sorbye H, Glimelius B, et al. EORTC Gastro-Intestinal Tract Cancer Group. Cancer Research UK. Arbeitsgruppe Lebermetastasen und-tumoren in der Chirurgischen Arbeitsgemeinschaft Onkologie (ALM-CAO) Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group (AGITG) Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive (FFCD) Perioperative chemotherapy with FOLFOX4 and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC Intergroup trial 40983): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9617):1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60455-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benoist S, Brouquet A, Penna C, et al. Complete response of colorectal liver metastases after chemotherapy: does it mean cure? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(24):3939–3945. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.8727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adam R, Wicherts D A, de Haas R J, et al. Complete pathologic response after preoperative chemotherapy for colorectal liver metastases: myth or reality? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1635–1641. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.7471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poston G J, Figueras J, Giuliante F, et al. Urgent need for a new staging system in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(29):4828–4833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.6453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Metcalfe M S, Mullin E J, Maddern G J. Choice of surveillance after hepatectomy for colorectal metastases. Arch Surg. 2004;139(7):749–754. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.7.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tomlinson J S, Jarnagin W R, DeMatteo R P, et al. Actual 10-year survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases defines cure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(29):4575–4580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]