ABSTRACT

In this article, the incidence, mortality, and survival rates for colorectal cancer are reviewed, with attention paid to regional variations and changes over time. A concise overview of known risk factors associated with colorectal cancer is provided, including familial and hereditary factors, as well as environmental lifestyle-related risk factors such as physical inactivity, obesity, smoking, and alcohol consumption.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, epidemiology, incidence, survival, risk factors

INCIDENCE OF COLORECTAL CANCER

Colorectal cancer is a major cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world.1 It accounts for over 9% of all cancer incidence.2,3 It is the third most common cancer worldwide and the fourth most common cause of death.2 It affects men and women almost equally, with just over 1 million new cases recorded in 2002, the most recent year for which international estimates are available.1,4,5,6 Countries with the highest incidence rates include Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, and parts of Europe. The countries with the lowest risk include China, India, and parts of Africa and South America.3

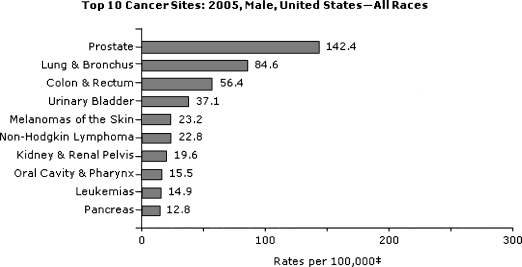

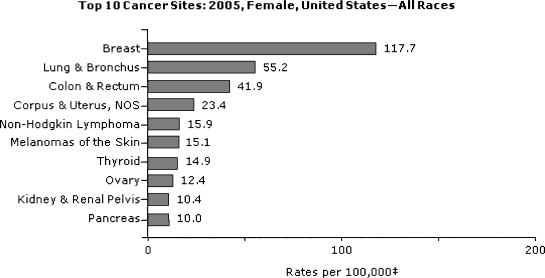

In the United States, colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer diagnosis among men and women (Figs. 1 and 2).7,8,9,10,11,12 There are similar incidence rates for cancer of the colon in both sexes, and a slight male predominance for rectal cancer.2,7,8 In 2005, the most recent year for which U.S. statistics are currently available, ~108,100 and 40,800 individuals were diagnosed with cancer of the colon and rectum, respectively.7 For 2008, it was estimated that ~148,900 new cases would be diagnosed and ~49,900 people would die of the disease.10,11,12

Figure 1.

Top 10 U.S. cancer sites in 2005: men, all races. From U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group.7

Figure 2.

Top 10 U.S. cancer sites in 2005: women, all races. From U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group.7

Geographic Variations

Worldwide, colorectal cancer represents 9.4% of all incident cancer in men and 10.1% in women. Colorectal cancer, however, is not uniformly common throughout the world.3 There is a large geographic difference in the global distribution of colorectal cancer. Colorectal cancer is mainly a disease of developed countries with a Western culture.3 In fact, the developed world accounts for over 63% of all cases.8 The incidence rate varies up to 10-fold between countries with the highest rates and those with the lowest rates.1,9 It ranges from more than 40 per 100,000 people in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and Western Europe to less than 5 per 100,000 in Africa and some parts of Asia.2 However, these incidence rates may be susceptible to ascertainment bias; there may be a high degree of underreporting in developing countries.

Temporal Trends

Different populations worldwide experience different incidence rates of colorectal cancer, and these rates change with time. In parts of Northern and Western Europe, the incidence of colorectal cancer may be stabilizing, and possibly declining gradually in the United States.10 Elsewhere, however, the incidence is increasing rapidly, particularly in countries with a high-income economy that have recently made the transition from a relatively low-income economy, such as Japan, Singapore, and Eastern European countries.2,3,8 Incidence rates have at least doubled in many of these countries since the mid-1970s.4,12,13

In the United States, male and female colorectal cancer incidence rates declined from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, followed by a short period of stabilization. From 1998 to 2005 incidence rates have again declined—an average of 2.8% per year for men and 2.2% per year among women.10 These decreases in colorectal cancer incidence have been largely attributed to screening programs that may have improved the detection of precancerous polyps.11 However, although national incidence rates have declined slightly over the last decade, the burden of disease remains high, and disproportionate within demographic subpopulations. For instance, before the 1980s, incidence rates for white men were higher than for black men and approximately equal for black and white women. Since that time, incidence rates have been higher for men than women, and higher among the black population versus the white population.

MORTALITY RATES AND TRENDS

Worldwide mortality attributable to colorectal cancer is approximately half that of the incidence. Nearly 530,000 deaths were recorded in 2002, that is, ~8% of all cancer deaths.2,8 It is estimated that 394,000 deaths from colorectal cancer still occur worldwide annually,3 making colorectal cancer the fourth most common cause of death from cancer.2,8 In the United States, colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of death among cancers that affect both men and women.7,8,9,10,11,12,14,15 It was estimated that ~49,960 people from the United States would die of the colorectal cancer in 2008.11,12,16

In North America, New Zealand, Australia, and Western Europe, mortality from colorectal cancer in both men and women has declined significantly.4 However, in some parts of Eastern Europe, mortality has been increasing by 5 to 15% every 5 years.8 In the United States, deaths from colorectal cancer have decreased significantly by 4.3% per year from 2002 to 2005.12 The age-standardized death rate was 18.8 per 100,000 men and women combined per year.17 The current trends in mortality statistics from many of the developed countries are encouraging. However, it is generally difficult to interpret temporal changes in mortality as they are influenced by trends over time in incidence and survival. The incidence rate may be a more appropriate indicator of trends in disease occurrence. Colorectal cancer incidence is unaffected by changes in treatment and survival, although it has been shown to be influenced by improved diagnostic techniques and screening programs.

CANCER SURVIVAL AND PROGNOSIS

Colorectal cancer survival is highly dependent upon stage of disease at diagnosis, and typically ranges from a 90% 5-year survival rate for cancers detected at the localized stage; 70% for regional; to 10% for people diagnosed for distant metastatic cancer.11,17 In general, the earlier the stage at diagnosis, the higher the chance of survival.

Since the 1960s, survival for colorectal cancer at all stages have increased substantially.11 The relative improvement in 5-year survival over this period and survival has been better in countries with high life-expectancy and good access to modern specialized health care. However, enormous disparities in colorectal cancer survival exist globally and even within regions.3,5,18 This variation is not easily explained, but most of the marked global and regional disparity in survival is likely due to differences in access to diagnostic and treatment services.3 In the United States, the 5-year survival for colorectal cancer improved from 1995 to 2000 by more than 10% for both men and women, from 52 to 63% in women and from 50 to 64% in men.11 The increase in survival during this period was not uniform among racial groups, however, and was reduced among non-whites compared with whites.12,17,18

NONMODIFIABLE RISKS FACTORS

Several risk factors are associated with the incidence of colorectal cancer. Those that an individual cannot control include age and hereditary factors. In addition, a substantial number of environmental and lifestyle risk factors may play an important role in the development of colorectal cancer; modifiable risks factors will be discussed in the next section.

Age

The likelihood of colorectal cancer diagnosis increases after the age of 40, increases progressively from age 40, rising sharply after age 50.2,17 More than 90% of colorectal cancer cases occur in people aged 50 or older.13,17 The incidence rate is more than 50 times higher in persons aged 60 to 79 years than in those younger than 40 years.17,19 However, colorectal cancer appears to be increasing among younger persons.20,21 In fact, in the United States, colorectal cancer is now one of the 10 most commonly diagnosed cancers among men and women aged 20 to 49 years.14

Tables 1 and 2 show the proportion of men or women in the United States who will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer over different time intervals.17 The time intervals are based on the person's current age.

Table 1.

Percentage of U.S. Men Who Develop Colorectal Cancer over 10-, 20- and 30-Year Intervals According to Their Current Age, 2003–2005

| Current Age | 10 Years | 20 Years | 30 Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 0.06 | 0.29 | 0.96 |

| 40 | 0.23 | 0.92 | 2.29 |

| 50 | 0.71 | 2.14 | 4.06 |

| 60 | 1.55 | 3.64 | 5.06 |

| 70 | 2.51 | 4.22 | N/A |

Table 2.

Percentage of U.S. Women Who Develop Colorectal Cancer over 10-, 20- and 30-Year Intervals According to Their Current Age, 2003–2005

| Current Age | 10 Years | 20 Years | 30 Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.78 |

| 40 | 0.20 | 0.72 | 1.74 |

| 50 | 0.54 | 1.58 | 3.16 |

| 60 | 1.10 | 2.76 | 4.29 |

| 70 | 1.88 | 3.61 | N/A |

Personal History of Adenomatous Polyps

Neoplastic polyps of the colorectum, namely tubular and villous adenomas, are precursor lesions of colorectal cancer.8 The lifetime risk of developing a colorectal adenoma is nearly 19% in the U.S. population.15 Nearly 95% of sporadic colorectal cancers develop from these adenomas.19 An individual with a history of adenomas has an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer, than individuals with no previous history of adenomas.16 A long latency period, estimated at 5 to 10 years, is usually required for the development of malignancy from adenomas.16,22 Detection and removal of an adenoma prior to malignant transformation may reduce the risk of colorectal cancer.23 However, complete removal of adenomatous polyp or localized carcinoma is associated with an increased likelihood of future development of metachronous cancer elsewhere in the colon and rectum.16

Personal History of Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a term used to describe two diseases, ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease. Ulcerative colitis causes inflammation of the mucosa of the colon and rectum. Crohn disease causes inflammation of the full thickness of the bowel wall and may involve any part of the digestive tract from the mouth to the anus. These conditions increase an individual's overall risk of developing colorectal cancer.13 The relative risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease has been estimated between 4- to 20-fold.8 Therefore, regardless of age individuals with IBD are highly encouraged to be screened for colorectal cancer on a more frequent basis.

Family History of Colorectal Cancer or Adenomatous Polyps

The majority of colorectal cancer cases occur in persons without a family history of colorectal cancer or a predisposing illness. Nevertheless, up to 20% of people who develop colorectal cancer have other family members who have been affected by this disease.2,24 People with a history of colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps in one or more first-degree relatives are at increased risk. It is higher in people with a stronger family history, such as a history of colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps in any first-degree relative younger than age 60; or a history of colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps in two or more first-degree relatives at any age.25 The reasons for the increased risk are not clear, but it likely due to inherited genes, shared environmental factors, or some combination of these.

Inherited Genetic Risk

Approximately 5 to 10% of colorectal cancers are a consequence of recognized hereditary conditions.18 The most common inherited conditions are familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), also called Lynch syndrome. Genes responsible for these forms of inherited colorectal cancer have been identified. HNPCC is associated with mutations in genes involved in the DNA repair pathway, namely the MLH1 and MSH2 genes, which are the responsible mutations in individuals with HNPCC.2,26 FAP is caused by mutations in the tumor suppressor gene APC.9

HNPCC may account for ~2 to 6% of colorectal cancers.2,13 The lifetime risk of colorectal cancer in people with the recognized HNPCC-related mutations may be as high as 70 to 80%,27,28 and the average age at diagnosis in their mid-40s.13 MLH1 and MSH2 mutations are also associated with an increased relative risk of several other cancers, including several extracolonic malignancies, namely cancer of the uterus, stomach, small bowel, pancreas, kidney, and ureter.2 FAP accounts for less than 1% of all colorectal cancer cases.2,13,22 Unlike individuals with HNPCC, who develop only a few adenomas, people with FAP characteristically develop hundreds of polyps, usually at a relatively young age, and one or more of these adenomas typically undergoes malignant transformation as early as age 20.22 By age 40, almost all people with this disorder will have developed cancer if the colon is not removed.2,13 APC-associated polyposis conditions are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Approximately 75 to 80% of individuals with APC-associated polyposis conditions have an affected parent. Prenatal testing and preimplantation genetic diagnosis are possible if a disease-causing mutation is identified in an affected family member.29

ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS

Colorectal cancer is widely considered to be an environmental disease, with “environmental” defined broadly to include a wide range of often ill-defined cultural, social, and lifestyle factors. As such, colorectal cancer is one of the major cancers for which modifiable causes may be readily identified, and a large proportion of cases theoretically preventable.3,30 Some of the evidence of environmental risk comes from studies of migrants and their offspring. Among migrants from low-risk to high-risk countries, incidence rates of colorectal cancer tend to increase toward those typical of the population of the host country.8,30 For example, among offspring of southern Europe migrants to Australia and Japanese migrants to Hawaii, the risk of colorectal cancer is increased in comparison with that of populations of the country of origin. In fact, colorectal cancer incidence in the offspring of Japanese migrants to the United States now approaches or surpasses that in the white population, and is three or four times higher than among the Japanese in Japan.2,3 Apart from migration, there are some other geographic factors influencing differences in incidence of colorectal cancer. One of them is urban residence. The incidence is consistently higher among urban residents. Current residence in an urban area is a stronger predictor of risk than is an urban location of birth.8 This excess incidence in urban areas is more apparent among men than women, and for colon cancer than for rectal cancer.3

Nutritional Practices

Diet strongly influences the risk of colorectal cancer, and changes in food habits might reduce up to 70% of this cancer burden.31 Diets high in fat, especially animal fat, are a major risk factor for colorectal cancer.3,8 The implication of fat, as a possible etiologic factor, is linked to the concept of the typical Western diet, which favors the development of a bacterial flora capable of degrading bile salts to potentially carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds.32 High meat consumption has also been implicated in the development of colorectal cancer.32,33 The positive association with meat consumption is stronger for colon cancer than rectal cancer.32 Potential underlying mechanisms for a positive association of red meat consumption with colorectal cancer include the presence of heme iron in red meat.33,34 In addition, some meats are cooked at high temperatures, resulting in the production of heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,33,35 both of which are believed to have carcinogenic properties. In addition, some studies suggest that people who eat a diet low in fruits and vegetables may have a higher risk of colorectal cancer.13 Differences in dietary fiber intake might have been responsible for the geographic differences in the colorectal incidence rates.8 For example, dietary fiber has been proposed as accounting for the differences in the rates of colorectal cancer between Africa and Westernized countries—on the basis that increased intake of dietary fiber may dilute fecal content, increase fecal bulk, and reduce transit time.2

Physical Activity and Obesity

Several lifestyle-related factors have been linked to colorectal cancer. Two modifiable and interrelated risk factors, physical inactivity and excess body weight, are reported to account for about a fourth to a third of colorectal cancers. There is abundant evidence that higher overall levels of physical activity are associated with a lower risk of colorectal cancer, including evidence of a dose–response effect, with frequency and intensity of physical activity inversely associated with risk.3,16,36 Regular physical activity and a healthy diet can help decrease the risk of colorectal cancer, although the evidence is stronger for colonic than for rectal disease.2,37 The biologic mechanisms potentially responsible for the association between reduced physical activity and colorectal cancer are beginning to be elucidated. Sustained moderate physical activity raises the metabolic rate and increases maximal oxygen uptake.16 In the long term, regular periods of such activity increase the body's metabolic efficiency and capacity, as well as reducing blood pressure and insulin resistance.36 In addition, physical activity increases gut motility.2 The lack of physical activity in daily routines also can be attributed to the increased incidence of obesity in men and women, another factor associated with colorectal cancer.16,38 Several biologic correlates of being overweight or obese, notably increased circulating estrogens and decreased insulin sensitivity, are believed to influence cancer risk, and are particularly associated with excess abdominal adiposity independent of overall body adiposity.16 However, the increased risk associated with overweight and obesity does not seem to result merely from increased energy intake; it may reflect differences in metabolic efficiency.16 Studies suggest that individuals who use energy more efficiently may be at a lower risk of colorectal cancer.3

Cigarette Smoking

The association between tobacco cigarette smoking and lung cancer is well established, but smoking also is extremely harmful to the colon and rectum. Evidence shows that 12% of colorectal cancer deaths are attributed to smoking.39 The carcinogens found in tobacco increase cancer growth in the colon and rectum, and increase the risk of being diagnosed with this cancer.13 It has been estimated that 12% of colorectal cancer deaths are attributable to smoking.39 Cigarette smoking is important for both formation and growth rate of adenomatous polyps, the recognized precursor lesions of colorectal cancer.40 Larger polyps found in the colon and rectum were associated with long-term smoking. Evidence also demonstrates an earlier average age of onset incidence of colorectal cancer among men and women who smoke cigarettes.39,41

Heavy Alcohol Consumption

As with smoking, the regular consumption of alcohol may be associated with increased risk of developing colorectal cancer. Alcohol consumption is a factor in the onset of colorectal cancer at a younger age,39,41 as well as a disproportionate increase of tumors in the distal colon.37 Reactive metabolites of alcohol such as acetaldehyde can be carcinogenic.42 There is also an interaction with smoking.39 Tobacco may induce specific mutations in DNA that are less efficiently repaired in the presence of alcohol.42 Alcohol may also function as a solvent, enhancing penetration of other carcinogenic molecules into mucosal cells.42 Additionally, the effects of alcohol may be mediated through the production of prostaglandins, lipid peroxidation, and the generation of free radical oxygen species.42 Lastly, high consumers of alcohol may have diets low in essential nutrients, making tissues susceptible to carcinogenesis.2

CONCLUSION

The transition from identification of theoretically avoidable causes of colorectal cancer to implementation of preventive strategies depends on the delineation of exposures considered to be causally associated with development of the disease. From analytical epidemiology, some clear ideas have now emerged about measures for reducing the burden of colorectal cancer. There are several factors considered to be causally associated with the development of colorectal cancer. For instance, the risk of colorectal cancer is clearly increased by a Western diet. Genes responsible for the most common forms of inherited colorectal cancer have also been identified. Fortunately, the vast majority of cases and deaths from colorectal cancer can be prevented by applying existing knowledge about cancer prevention. Appropriate dietary changes, regular physical activity, and maintenance of healthy weight, together with targeted screening programs and early therapeutic intervention could, in time, substantially reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with colorectal cancer.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. Lyon: The World Health Organization and The International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2002.

- 2.World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2007.

- 3.Boyle P, Langman J S. ABC of colorectal cancer: Epidemiology. BMJ. 2000;321(7264):805–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7264.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyle P, Ferlay J. Mortality and survival in breast and colorectal cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2(9):424–425. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parkin D, Bray F, Ferlay J. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferlay J, Bray F, Pisani P, Parkin D M. GLOBOCAN 2002: Cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2004.

- 7.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2005 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & National Cancer Institute; 2009. Accessed October 21, 2009. Available at: www.cdc.gov/uscs

- 8.Janout V, Kollárová H. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacku Olomouc Czech Repub. 2001;145:5–10. doi: 10.5507/bp.2001.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilmink A BM. Overview of the epidemiology of colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40(4):483–493. doi: 10.1007/BF02258397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jemal A, Thun M J, Ries L A, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2005, featuring trends in lung cancer, tobacco use, and tobacco control. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1672–1694. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jemal A, Clegg L X, Ward E, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101(1):3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Cancer Society Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2009–2010. Oklahoma City, OK: American Cancer Society; 2009; Accessed May 26, 2009. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/docroot/STT/stt_0.asp

- 13.National Institutes of Health What You Need To Know About Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & National Institutes of Health; 2006.

- 14.Fairley T L, Cardinez C J, Martin J, et al. Colorectal cancer in U.S. adults younger than 50 years of age, 1998-2001. Cancer. 2006;107(5, Suppl):1153–1161. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labianca R, Beretta G D, Mosconi S, Milesi L, Pessi M A. Colorectal cancer: screening. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(Suppl 2):ii127–ii132. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Jong A E, Morreau H, Nagengast F M, et al. Prevalence of adenomas among young individuals at average risk for colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(1):139–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ries L AG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2005. Bethesda, MD: 2008.

- 18.Jackson-Thompson J, Ahmed F, German R R, Lai S M, Friedman C. Descriptive epidemiology of colorectal cancer in the United States, 1998-2001. Cancer. 2006;107(5, Suppl):1103–1111. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Cancer Society Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures Special Edition 2005. Oklahoma City, OK: American Cancer Society; 2005; Accessed May 26, 2009. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/docroot/STT/stt_0.asp

- 20.O'Connell J B, Maggard M A, Liu J H, et al. Rates of colon and rectal cancers are increasing in young adults. Am Surg. 2003;2003(69):866–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Connell J B, Maggard M A, Livingston E H, Yo C K. Colorectal cancer in the young. Am J Surg. 2004;187(3):343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies R J, Miller R, Coleman N. Colorectal cancer screening: prospects for molecular stool analysis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:199–209. doi: 10.1038/nrc1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grande M, Milito G, Attina G M, et al. Evaluation of clinical, laboratory and morphologic prognostic factors in colon cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:98. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-6-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skibber J, Minsky B, Hoff P. In: DeVita VT Jr, Hellmann S, Rosenberg SA, editor. Cancer: principles & practice of oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Cancer of the colon and rectum. pp. 1216–1271.

- 25.Boardman L A, Morlan B W, Rabe K G, et al. Colorectal cancer risks in relatives of young-onset cases: is risk the same across all first-degree relatives? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(10):1195–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papadopoulos N, Nicolaides N C, Wei Y F, et al. Mutation of a mutL homolog in hereditary colon cancer. Science. 1994;263(5153):1625–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.8128251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeter J M, Kohlmann W, Gruber S B. Genetics of colorectal cancer. Oncology. 2006;20(3):269–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Sukhni W, Aronson M, Gallinger S. Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes: familial adenomatous polyposis and lynch syndrome. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88(4):819–844, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynch H T, Lynch J F, Lynch P M, Attard T. Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes: molecular genetics, genetic counseling, diagnosis and management. Fam Cancer. 2008;7(1):27–39. doi: 10.1007/s10689-007-9165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson I T, Lund E K. Review article: nutrition, obesity and colorectal cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(2):161–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willett W C. Diet and cancer: an evolving picture. JAMA. 2005;293(2):233–234. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larsson S C, Wolk A. Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(11):2657–2664. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santarelli R L, Pierre F, Corpet D E. Processed meat and colorectal cancer: a review of epidemiologic and experimental evidence. Nutr Cancer. 2008;60(2):131–144. doi: 10.1080/01635580701684872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kabat G C, Miller A B, Jain M, Rohan T E. A cohort study of dietary iron and heme iron intake and risk of colorectal cancer in women. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(1):118–122. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinha R. An epidemiologic approach to studying heterocyclic amines. Mutat Res. 2002;506–507:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee K J, Inoue M, Otani T, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Tsugane S, JPHC Study Group Physical activity and risk of colorectal cancer in Japanese men and women: the Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(2):199–209. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bazensky I, Shoobridge-Moran C, Yoder L H. Colorectal cancer: an overview of the epidemiology, risk factors, symptoms, and screening guidelines. Medsurg Nurs. 2007;16(1):46–51. quiz 52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campbell P T, Cotterchio M, Dicks E, Parfrey P, Gallinger S, McLaughlin J R. Excess body weight and colorectal cancer risk in Canada: associations in subgroups of clinically defined familial risk of cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(9):1735–1744. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zisman A L, Nickolov A, Brand R E, Gorchow A, Roy H K. Associations between the age at diagnosis and location of colorectal cancer and the use of alcohol and tobacco: implications for screening. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(6):629–634. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Botteri E, Iodice S, Raimondi S, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels A B. Cigarette smoking and adenomatous polyps: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(2):388–395; e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsong W H, Koh W P, Yuan J M, Wang R, Sun C L, Yu M C. Cigarettes and alcohol in relation to colorectal cancer: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(5):821–827. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pöschl G, Seitz H K. Alcohol and cancer. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39(3):155–165. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]