Abstract

The role of phospholipase D (PLD) in the regulation of the traffic of the PTH type 1 receptor (PTH1R) was studied in Chinese hamster ovary cells stably transfected with a human PTH1R (CHO-R3) and in rat osteosarcoma 17/2.8 (ROS) cells. PTH(1–34) increased total PLD activity by 3-fold in CHO-R3 cells and by 2-fold in ROS cells. Overexpression of wild-type (WT) PLD1 and WT-PLD2 increased basal PLD activity in CHO-R3 but not in ROS cells. Ligand-stimulated PLD activity greatly increased in CHO-R3 cells transfected with WT-PLD1 and WT-PLD2. However, only WT-PLD2 expression increased PTH-dependent PLD activity in ROS cells. Expression of the catalytically inactive mutants R898K-PLD1 (DN-PLD1) and R758K-PLD2 (DN-PLD2) inhibited ligand-dependent PLD activity in both cell lines. PTH(1–34) induced internalization of the PTH1R with a concomitant increase in the colocalization of the receptor with PLD1 in intracellular vesicles and in a perinuclear, ADP ribosylation factor-1-positive compartment. The distribution of PLD1 and PLD2 remained unaltered after PTH treatment. Expression of DN-PLD1 had a small effect on endocytosis of the PTH1R; however, DN-PLD1 prevented accumulation of the PTH1R in the perinuclear compartment. Expression of DN-PLD2 significantly retarded ligand-induced PTH1R internalization in both cell lines. The differential effects of PLD1 and PLD2 on receptor traffic were confirmed using isoform-specific short hairpin RNA constructs. We conclude that PLD1 and PLD2 play distinct roles in regulating PTH1R traffic; PLD2 primarily regulates endocytosis, whereas PLD1 regulates receptor internalization and intracellular receptor traffic.

Phospholipases D1 and D2 (PLD1 and PLD2) regulate the traffic and function of the Type I parathyroid hormone receptor. Whereas PLD1 regulates intracellular receptor traffic, PLD2 activation plays an important role in ligand-dependent PTH1R internalization and activation of the ERK cascade.

PTH regulates calcium and phosphate homeostasis by acting primarily on target cells in bone and kidney. PTH function is mediated by the PTH type 1 receptor (PTH1R), a member of the B family of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR). Agonist binding to the PTH1R leads to activation of adenylyl cyclase and phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (1,2,3). PTH binding to the PTH1R results in the internalization of the ligand-receptor complex via clathrin-coated pits by a mechanism that involves arrestin (4,5,6,7). Recent data suggest that regulated GPCR endocytosis is a complex multistep process that involves the catalytic action of several lipid-modifying enzymes (8,9).

Phospholipases D (PLD) hydrolyze phosphatidylcholine to generate choline and the bioactive lipid phosphatidic acid. These enzymes have been implicated in signal transduction, membrane trafficking, transformation, and cytoskeletal reorganization (10,11,12,13,14,15). Two mammalian PLD isoforms have been identified, PLD1 (10) and PLD2 (16). Both are expressed in a wide but selective variety of tissues and cells (17,18). Numerous reports based on overexpression have proposed that PLD2 acts at the plasma membrane to regulate cortical cytoskeletal reorganization, endocytosis, and receptor signaling (14,19,20,21,22,23). Overexpression of catalytically inactive mutants of PLD1 inhibited the down-regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor in response to epidermal growth factor (24), and expression of a catalytically inactive mutant of PLD2 perturbed agonist-induced internalization of angiotensin (19) and μ-opioid receptors (13). Phagocytosis was also inhibited by expression of truncated or catalytically inactive PLD2 (25,26).

Previous work showed that PTH stimulates PLD activity in UMR-106 osteoblastic cells (27). The pathway appears to involve the heterotrimeric G proteins G12/13 and the subsequent activation of RhoA (27). However, the physiological role of PLD activation in PTH function has not been established.

In the present study, we investigated the role of PLD activity in PTH1R internalization using two cells models: CHO cells that express an HA-tagged human PTH1R (CHO-R3 cells) and rat osteosarcoma ROS 17/2.8 (ROS) cells, which express endogenous PTH receptors. We show here that PTH(1–34) activates both PLD1 and PLD2 in CHO-R3 cells, although activating primarily the PLD2 isoform in ROS cells. We further demonstrate that both PLD1 and PLD2 play an important role in the regulation of PTH1R traffic; although PLD2 activity is essential for PTH1R endocytosis, PLD1 regulates the intracellular traffic of the receptor.

Results

PTH(1–34) stimulates PLD activity in CHO-R3 and ROS cells

The intracellular distribution of PLD in cultured CHO-R3 cells was investigated by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. The subcellular distributions of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-PLD1 and EGFP-PLD2 are shown in Fig. 1A. PLD1 localizes primarily to endosomal vesicles and to a perinuclear region, as reported previously by us and others (28,29,30). Some localization of EGFP-PLD1 on the plasma membrane was observed occasionally. In contrast, PLD2 was detected primarily in the plasma membrane and vesicles close to plasma membrane as described (16). Identical results were obtained with ROS 17/2.8 cells.

Figure 1.

Localization of EGFP-PLD and EGFP-PLD2 in CHO-R3 cells. A, CHO-R3 cells were transiently transfected with PLD1-EGFP or PLD2-EGFP expression plasmids. Forty-eight hours later, images were captured by confocal microscopy (Olympus Fluoview 1000). EGFP fluorescence was used to determine the subcellular localization of the transfected proteins. B, The expression of endogenous and transfected PLD1 and PLD2 in CHO-R3 and ROS cells was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. The numbers of copies reported in the figure were obtained using standard curves generated by serial dilutions of plasmid DNA coding for the WT human PLD1 and mouse PLD2.

The expression of PLD1 and PLD2 in CHO and ROS cells was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. The data, shown in Fig. 1B, confirm the endogenous expression of PLD1 and PLD2 in both cell lines. We also determined the levels of expression of PLD1 and PLD2 after transfection with our PLD-EGFP constructs. The endogenous mRNA levels for both PLDs were comparable for CHO-R3 and ROS cells. The number of copies of PLD1 mRNA was 3.8 × 104 in CHO-R3 cells and 1.5 × 104 in ROS cells. PLD2 mRNA was significantly less abundant (2300 and 5300 copies for CHO-R3 and ROS cells, respectively). As shown in Fig. 1B, transfection with EGFP-PLD1 and EGFP-PLD2 increased expression by 4- to 20-fold. Actual protein levels could not be determined because of the lack of good specific antibodies. Similar transfection efficiencies were observed for CHO-R3 and ROS cells in all experiments.

PTH(1–34) increased PLD activity about 2.2-fold in CHO-R3 cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Similar but less dramatic results were observed in ROS cells (Fig. 2B). To determine which PLD isoforms are stimulated by PTH treatment, CHO-R3 and ROS cells were transfected with either wild-type (WT)-EGFP-PLD1 or WT-EGFP-PLD2 and treated with PTH(1–34) for 30 min. Both PLD constructs increased basal PLD activity in CHO-R3 cells (Fig. 2C) but had no significant effects on the basal PLD activity of ROS cells (Fig. 2D). PTH(1–34) treatment produced a pronounced increase in PLD activity in CHO-R3 cells transfected with either WT construct (Fig. 2C). In contrast, only ROS cells transfected with WT-EGFP-PLD2 showed an increased response to the addition of ligand (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that the PTH1R can activate both PLD1 and PLD2 in CHO cells but activates preferentially PLD2 in ROS cells. Interestingly, the effects were much greater in CHO-R3 cells than in ROS cells. This is possibly a consequence of the much larger number of receptors expressed in the CHO-R3, which express 650,000 receptors per cell (31), whereas the ROS cells express about 72,000 endogenous receptors per cell (32). Transfection of the catalytically inactive (dominant-negative, or DN) mutants DN-PLD1 or DN-PLD2 blocked PTH-induced PLD activity in both cell lines (Fig. 2, C and D).

Figure 2.

PTH1R-mediated PLD activation. A, Time course of the activation of PLD by PTH(1–34) (100 nm) in CHO-R3 cells. B, Time course of the activation of PLD by PTH(1–34) (100 nm) in ROS 17/2.8 cells. C, CHO-R3 cells stably expressing HA-PTH1R (control) were transfected with EGFP-tagged WT-PLD1 and -PLD2 and with the EGFP-tagged mutants K898R-PLD1 (DN-PLD1) and R758K-PLD2 (DN-PLD2). Cells were stimulated with PTH(1–34) for 30 min. Graphs represents a mean ± se of three independent experiments. The inset shows only the mock, DN-PLD1, and DN-PLD2 data. D, ROS cells were transfected with EGFP-tagged WT and mutant PLDs and treated with PTH(1–34). The graph represents a mean ± se of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 compared with the respective controls (time = 0 for the kinetics experiments shown in A and B and untreated cells for the data shown in C and D).

PLD activity regulates PTH1R traffic

A cell sorting-based assay was developed to investigate the role of PLD in the regulation of PTH1R internalization. This assay makes use of a human PTH1R tagged with an hemagglutinin (HA) epitope near the N terminus. This epitope faces the extracellular milieu such that only the receptor expressed on the surface of the cell is accessible to anti-HA antibodies added to intact, nonpermeabilized cells. Upon receptor internalization, the immunoreactivity of the cells decreases as a function of time. This time-dependent change is then detected by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or by indirect immunofluorescence. A representative FACS experiment performed with CHO-R3 cells is shown in Fig. 3 (see Materials and Methods for a complete description of the protocol). Figure 3A shows the selection of appropriate gates to detect the HA-tagged receptor. These gates were obtained by 1) transfecting cells with untagged receptors or 2) omitting the HA-specific primary antibody. Figure 3B shows histograms of the data shown in Fig. 3A. The 10-min points are omitted for the sake of clarity. As shown, the fluorescence of the cells decreases as a function of time after the addition of PTH(1–34).

Figure 3.

FACS analysis of the internalization of the PTH1R. A, Representative traces showing control cells (CHO cells not expressing HA-tagged PTH1R, left) and CHO-R3 cells after various times (0, 10, or 30 min) of incubation with 100 nm PTH(1–34). B, Histogram representation of the data shown in A. The 10-min point has been eliminated for the sake of clarity.

The effects of PLD on ligand-induced internalization of the PTH1R in CHO-R3 cells are shown in Fig. 4. WT-PLD2 had no effects on the internalization of the PTH1R (Fig. 4A). DN-PLD2, in contrast, significantly slowed receptor internalization (Fig. 4A). Both WT- and DN-PLD1 decreased the rate of PTH1R internalization after addition of ligand (Fig. 4B). Importantly, the level of expression of the HA-tagged receptors in cells that overexpressed WT-PLD1 or DN-PLD1 was significantly reduced (Fig. 4C). Thus, we conclude that the activities of PLD1 and PLD2 modulate the rate of PTH1R internalization; furthermore, we conclude that regulated PLD1 activity is required for efficient traffic of the PTH1R to the plasma membrane.

Figure 4.

Phospholipase D activity regulates PTH1R internalization and traffic. A, CHO-R3 cells stably expressing HA-PTH1R were transiently transfected with EGFP-PLD2 (WT) or R758K-PLD2 (DN). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were stimulated with PTH(1–34) for 0, 10, or 30 min and analyzed by FACS using a specific anti-HA antibody. Cells successfully transfected were identified by GFP fluorescence. Only GFP-positive cells were used in the analysis. The data shown have been normalized to the initial integrated cell fluorescence. B, Same as A, except that WT and R898K (DN) PLD1 were used. C, PTH1R internalization data normalized to the mock transfection values. Notice the much lower starting points of the cells that express WT- and DN-PLD1. D, Expression of the PTH1R on the cell membrane is inhibited by overexpression of WT- and DN-PLD1. CHO-R3 cells transfected with PLD1 were examined by FACS after 48 h. The total cell-associated PTH1R fluorescence of the transfected cells was compared with the fluorescence of paired, mock transfected cells or to that of nontransfected cells. Both comparisons yielded identical results. The data shown represent the averages from three different experiments. *, P < 0.01 vs. mock.

Confocal studies on the regulation of the traffic of the PTH1R by PLD1 and PLD2

PTH1R traffic was further studied by confocal microscopy. CHO-R3 cells were treated with PTH(1–34) for various times and fixed, and the distribution of the HA-tagged PTH1R was determined using anti-HA antibodies and a tetramethylrhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody. Transfections with empty vectors were used as controls. The distribution of EGFP-PLD1 was determined from the GFP fluorescence of the cells. The data are shown in Fig. 5. Before the addition of PTH(1–34), the receptor was expressed on the cell surface and in intracellular vesicles. WT-PLD1 and DN-PLD1 were primarily localized to the cytosol or to intracellular vesicles, some of which were also decorated with the PTH1R. Significant reorganization of the PTH1R and PLD labels was observed within 10 min of the addition of ligand; the PTH1R disappeared from the membrane and was localized to vesicles (probably early endosomes, see Fig. 9) that were also decorated with PLD1. Thirty minutes after ligand addition, the PTH1R accumulated in the perinuclear compartment. Importantly, WT-PLD1-EGFP colocalized with the receptor in this perinuclear compartment (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

PLD1 alters PTH1R traffic in CHO cells. CHO-R3 were transiently transfected with WT EGFP-PLD1 (A) or EGFP-tagged K898R-PLD1 (DN-PLD1; (B). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were stimulated with PTH(1–34) for 0, 10, or 30 min. Cells were visualized using an anti-HA antibody and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Representative images are shown from more than 45 cells analyzed across four independent experiments. C, Correlation coefficients were calculated at different times for regions comprising most of the cell. The graph represents the mean ± se of four independent experiments. More than 35 individual cells were analyzed for each data point.

Figure 9.

Inhibition of PTH1R endocytosis by DN-PLD2 in ROS 17/2.8 cells. ROS cells coexpressing HA-PTH1R (control) and EGFP-tagged DN-PLD2 mutant were treated with PTH(1–34) for 0, 10, or 30 min and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Representative images are shown from more than 25 cells analyzed per slide across three independent experiments, each in duplicate.

The intracellular distribution of DN-PLD1 was somewhat different. DN-PLD1 was seldom found in perinuclear compartments before or after addition of PTH(1–34). The expression of DN-PLD1 significantly affected the traffic of the internalized receptor. Receptor internalization appeared to be slower, and the accumulation of the internalized PTH1R in the perinuclear region was never observed. Rather, the internalized receptor remained in small intracellular vesicles, where it colocalized abundantly with DN-EGFP-PLD1 (Fig. 5B, 30 min). A quantitative description of these phenomena was obtained by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient of the red and green fluorescence of images obtained from 35–45 cells from at least 5 independent experiments. The correlation between PTH1R and WT-PLD1 increased significantly as a function of time (P < 0.01), indicative of a time-dependent accumulation of both labels in common cellular compartments (Fig. 5C). A much slower, but similar, phenomenon was observed with DN-PLD1. The increased colocalization between PTH1R and DN-PLD1 only became significant 30 min after the addition of ligand (Fig. 5C).

In parallel studies, CHO-R3 cells were transfected with WT- and DN-PLD2 and stimulated with PTH(1–34) for 10 and 30 min. In nontransfected or WT-PLD2-transfected cells, the PTH1R showed a vesicular distribution 10 and 30 min after treatment with PTH(1–34). Significant accumulation of the receptor in the perinuclear compartment was visible after 30 min (Fig. 6A). However, most of the PLD2 remained at the plasma membrane, although a small fraction of the PLD2 trafficked with the PTH1R to the perinuclear compartment. In marked contrast, little internalization of the receptor was apparent even after 30 min in cells that were transfected with DN-PLD2. In fact, a significant fraction of the cells expressing DN-PLD2 did not internalize the receptor at all (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

PLD2 delays PTH1R endocytosis in CHO cells. CHO-R3 cells were transiently transfected with WT EGFP-PLD2 (A) or EGFP-tagged K758R-PLD2 (DN-PLD2; B). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were stimulated with PTH(1–34) for 0, 10, or 30 min. Cells were visualized using an anti-HA antibody and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Representative images are shown from more than 45 cells analyzed across four independent experiments. C, Correlation coefficients were calculated at different times for regions comprising most of the cell. The graph represents the mean ± se of four independent experiments. At least 35 individual cells were analyzed for each data point.

In contrast to PLD1, which colocalized with the internalized PTH1R in vesicles and in the perinuclear compartment, the distribution of WT-EGFP-PLD2 remained unchanged after PTH1R stimulation, independently of the traffic of the receptor. A quantitative analysis of the colocalization data are shown in Fig. 6C. The Pearson correlation coefficient of the fluorescent images obtained with the WT-PLD2 construct and the HA-tagged receptor decreased as a function of time as a consequence of the disappearance of the PTH1R from the plasma membrane surface and the retention of the PLD2 construct on the surface (Fig. 6C). In contrast, the correlation coefficients of the fluorescent images obtained with the DN construct remained approximately constant, indicative of the much slower internalization of the PTH1R.

PTH1R internalization in ROS cells

To examine the regulation of PTH1R endocytic traffic in a more physiologically relevant cellular system, we investigated ligand-induced redistribution of the PTH1R in ROS cells. This was done using ROS cells transfected with HA-tagged human PTH1R.

As shown in Fig. 7, HA-tagged PTH1R was localized primarily on the plasma membrane of untreated ROS cells. Occasionally, a fraction of the receptor was found in a perinuclear compartment, which was also decorated with ADP ribosylation factor-1 (ARF1), consistent with the Golgi compartment. Thirty minutes after treatment with PTH(1–34), the plasma membrane receptor had accumulated in numerous intracellular vesicles and the Golgi compartment.

Figure 7.

PTH1R colocalizes with ARF1 after PTH(1–34) treatment. CHO-R3 cells were transfected with ARF1-EGFP and stimulated with PTH(1–34) (100 nm) for 0 or 30 min. The cells were then fixed, permeabilized, immunostained with anti-HA antibodies, and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Representative images are shown from more than 25 cells analyzed per slide across three independent experiments.

Further details of the endocytic traffic of the PTH1R in ROS cells are illustrated in Fig. 8. Some colocalization of the PTH1R with early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1) was observed even under basal conditions (red-green correlation coefficient, 0.34 ± 0.112) (Fig. 8). However, addition of PTH(1–34) increased significantly the colocalization of the PTH1R with EEA1 (red-green correlation coefficient, 0.857 ± 0.097) (Fig. 8). This demonstrates that the receptor traffics via the standard endocytic pathway. Figure 9 shows that DN-PLD2 impairs the endocytosis of the PTH1R in ROS cells in a manner analogous to that described for CHO-R3 cells. Transfection with DN-PLD1 greatly reduced the expression of the HA-tagged PTH1R on the surface in ROS cells, precluding the analysis of the effects of DN-PLD1 on receptor internalization (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Internalized PTH1R colocalizes transiently with EEA1. CHO-R3 cells were stimulated with PTH(1–34) (100 nm) for 0, 10, or 30 min. The cells were then fixed, permeabilized, immunostained with anti-HA and anti-EEA1 antibodies, and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Representative images are shown from more than 25 cells analyzed per slide across three independent experiments, each in duplicate.

To confirm that the results obtained by overexpression of catalytically inactive PLD were a consequence of reduced PLD activity, we generated ROS-derived cell lines that expressed short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeted against PLD1 and PLD2 in a stable manner. PLD expression was determined by semiquantitative PCR. The constructs used reduced PLD1 and PLD2 expression by at least 90% in a specific manner (Fig. 10A). PTH1R internalization was determined using the cell-sorting protocol described in Materials and Methods. The knockdown of PLD1 reduced PTH1R expression on the surface by about 50% and reduced the rate of PTH1R internalization (Fig. 10, B and C), confirming the DN-PLD1 data. Likewise, PLD2 knockdown significantly reduced PTH1R internalization (Fig. 10, B and D). Importantly, expression of mouse WT-PLD2 or addition of exogenous phosphatidic acid normalized PTH1R internalization (Fig. 10D). Transfection of the cells expressing PLD2-targeted shRNA with human WT-PLD1, however, did not rescue the effects of PLD2 knockdown on PTH(1–34)-induced internalization of the receptor. These data confirm that PLD2 activation is required for PTH1R internalization, whereas PLD1 activity affects both internalization and traffic of the PTH1R to the cell surface.

Figure 10.

Knockdown of PLD1 and PLD2 affects differentially the traffic of the PTH1R in ROS 17/2.8 cells. A, Knockdown of PLD1 and PLD2 with shRNA. ROS cells were transfected with plasmids coding for PLD1- and PLD2-specific shRNA (shPLD2) or with a plasmid coding for a scrambled shRNA construct. Transfected cells were selected with G418 for at least 2 wk. PLD1 and PLD2 expression was measured using semiquantitative PCR. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression was used as internal control. As shown, the transfected cells express reduced levels of PLD1 or PLD2 mRNA. B, Knockdown of PLD1 and PLD2 reduces the rate of internalization of the PTH1R. C, PLD1 knockdown reduces the expression of the PTH1R on the surface. D, Treatment with PA (100 μm dioleoyl PA) or overexpression of mouse WT-PLD2 reverts the effects of PLD2 knockdown on PTH1R internalization. In contrast, expression of human PLD1 cannot normalize PTH1R internalization. ***, P < 0.005.

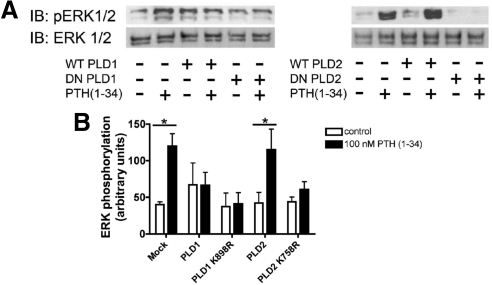

Phospholipase D activity is required to couple PTH1R activation to ERK phosphorylation

Previous work from our lab demonstrated that PLD activity is required to couple the function of several cell surface receptors to the activation of the ERK cascade (14,15,33,34,35,36). In this work, we extended this paradigm to PTH1R signaling in CHO-R3 cells. The data obtained are summarized in Fig. 10. Expression of WT-PLD1 had a small effect on the basal level of phosphorylation of ERK. The expression of WT-PLD2 did not alter the effects of PTH(1–34) on ERK phosphorylation. Importantly, the expression of the DN mutants DN-PLD1 and DN-PLD2, both of which block PTH-induced PLD activation, also abolished the effects of PTH on ERK phosphorylation. We conclude, therefore, that the activation of PLD and the generation of phosphatidic acid are required for the activation of the ERK cascade by PTH.

Discussion

Agonist-induced activation of PLD plays an important role in regulating numerous signal transduction pathways. These include receptor internalization (19,24,37), receptor desensitization and resensitization, and protein phosphorylation (14,22,23,34,38). Several members of the GPCR family activate PLD (27,35,36,39,40,41). The PTH1R activates PLD in kidney (3) and bone (27). However, the physiological significance of this activity has not been elucidated. We show here that PLD activity regulates the traffic of the PTH1R to the plasma membrane, PTH1R endocytosis, and PTH-dependent ERK phosphorylation.

Mammalian cells express two main forms of PLD (10,16,42). Both PLD isoforms display distinct subcellular distributions and modes of regulation. PLD1 localizes to intracellular vesicles and was implicated initially in various aspects of vesicular traffic (28,29,30). PLD2 is expressed primarily at the plasma membrane and was identified as the main target for receptor-mediated activation and a regulator of ligand-dependent endocytosis (13,14,19,35,37). Subsequent work, however, suggests that PLD1 may play additional roles in specific signaling pathways. Recent evidence shows that a small fraction of PLD1 localizes to the plasma membrane where it contributes to mediating specific signaling events (43,44). We investigated the activation of specific PLD isoforms by the PTH1R using two complementary approaches based on the overexpression of WT and DN mutants. Our results demonstrate cell-dependent specificity in the activation of PLD1 and PLD2 by the PTH1R. Whereas both PLD1 and PLD2 appear to be targets in CHO-R3 cells, only PLD2 seems to be activated by the PTH1R in ROS osteosarcoma cells. However, the expression of catalytically inactive mutants of both isoforms significantly inhibited PTH-induced PLD activity suggesting, superficially, that the activation of both PLDs by the PTH1R follow common signaling pathways. This, however, is not necessarily the case, as will be discussed below.

Activation of PLD2 by the PTH1R is consistent with several reports linking receptor-dependent PLD activation to the PLD2 isoform. (13,15,19,23,35,37,41). In contrast, whereas PLD2 is expressed at the plasma membrane, PLD1 is mostly confined to the cytosol and intracellular membranes in CHO-R3 and ROS cells. However, localization of the PTH1R with PLD1 increases significantly after the addition of ligand owing primarily to the accumulation of PTH1R in endosomes enriched in PLD1. It is possible, therefore, that the PTH1R activates PLD1 and PLD2 in different compartments and in a distinct temporal pattern; PLD2 is activated early and at the plasma membrane, whereas PLD1 activation may occur only after the receptor is internalized and translocated to endosomes.

Interestingly, although PTH effectively activated PLD1 in CHO-R3 cells, we did not find evidence of PTH1R-dependent activation of PLD1 in ROS cells. The cell and tissue specificity of the responses to PTH1R ligands has been abundantly described (3,5,45,46). One explanation for this specificity is based the relative levels of expression of NHERF1 (5,46). However, neither CHO-R3 (7) nor ROS cells (46,47) express endogenous NHERF1. Therefore, different levels of NHERF1 expression cannot explain these results.

Importantly, our data demonstrate that altered PLD1 activity, caused by overexpression of the WT protein, by expression of a DN construct, or by shRNA knockdown, significantly reduces the plasma membrane expression of the PTH1R. This result strongly suggests that regulated PLD1 activity is required for the normal traffic of the receptor to the surface. Whether this finding can be extrapolated to other receptors remains to be determined. Nevertheless, this result raises an important issue; studies in which receptor-mediated PLD1 activation is perturbed by expression of a DN or by shRNA techniques must be carefully controlled, because reduced surface expression of the receptor may be a consequence of the perturbation of PLD1 activity. Thus, the mechanism by which PLD1 knockdown and expression of DN-PLD1 impair receptor-mediated PLD activation is not necessarily a consequence of the interference of these treatments with stimulation of endogenous PLD. We cannot distinguish between these alternative explanations at present.

Ligand-induced internalization of GPCR plays a major role in the regulation of signal transduction pathways, either by propagating (48,49) or terminating (50) signals. Our data strongly support the hypothesis that PLD activation regulates PTH1R internalization, thereby contributing to signal termination. DN-PLD2 expression significantly reduced the rate of receptor internalization in CHO-R3 and ROS cells. The expression of WT-PLD2 was without effect. This is the first time that the activation of PLD2 has been linked to the internalization of the PTH1R. This observation, however, is consistent with results obtained with other receptor systems and in diverse cell lines (13,19,21,24,37).

The role of PLD1 on PTH1R internalization is somewhat different. Both WT- and DN-PLD1 significantly reduced the level of expression of the PTH1R on the cell surface. In CHO-R3 cells, plasma membrane expression of the PTH1R was reduced by 50 and 75% by WT-PLD1 and DN-PLD1, respectively, whereas in ROS cells, HA-tagged PTH1R was essentially undetectable in cells transfected with either WT-PLD1 or DN-PLD1. In independent experiments, PLD1 knockdown using shRNA reduced surface PTH1R expression by about 50% in ROS cells, whereas PLD2 knockdown had no effects. These observations imply that PLD1 plays an important role in regulating the traffic of the receptor to the plasma membrane and thus contributing to signal propagation. The precise function of PLD1 in PTH1R traffic, however, remains to be elucidated.

In addition, PLD1 function also regulates the traffic of the internalized receptor. Internalized receptor accumulates initially in endosomes (Fig. 8) and, after several minutes, in a perinuclear compartment (Figs. 5–7). Because this compartment is also decorated with ARF1 (Fig. 7), we conclude it is the Golgi apparatus. In CHO-R3 cells, PLD1 accompanies the receptor throughout this process (see Fig. 5). However, in cells expressing DN-PLD1, accumulation of the receptor in the Golgi was not observed. Thus, we conclude that in the absence of PLD1 activity, the traffic of the PTH1R is interrupted, such that the receptor never reaches the Golgi.

The present data also demonstrate the requirement for PLD activity in the regulation of the ERK cascade by PTH(1–34). PTH treatment induced ERK phosphorylation, as described previously (51), and this effect was inhibited by overexpression of DN-PLD2 (Fig. 11). WT- and DN-PLD1 had similar effects, but because of the reduced expression of PTH1R on the surface of cells transfected with exogenous PLD1, we cannot conclude that the effects of PLD1 are related to the coupling of the ERK cascade to PTH1R function. The effects of DN-PLD2 on ERK phosphorylation are consistent with the reduced internalization of the PTH1R caused by expression of this mutant protein. Several lines of evidence link endocytosis to the activation of the ERK cascade. These include specific roles for β-arrestins as scaffolds (48,50,52) and other less characterized effects of endocytic traffic (53,54,55,56). More recently, a specific role for PA as a scaffold for the coupling of the ERK cascade has emerged. This model is based on the fact that Son of Sevenless (SOS; a Ras guanine-nucleotide exchange factor), Raf-1, and kinase supressor of Ras 1 (a scaffolding protein that binds ERK1/2 and MAPK/ERK kinase 1) contain specific binding sites for phosphatidic acid and require phosphatidate binding for function (14,15,23,33,57). Our data are compatible with both of these models, and some additional work will be required to determine the mechanisms by which PLD activation is required for induction of the ERK cascade by PTH.

Figure 11.

PLD activity is necessary for PTH-dependent ERK phosphorylation. CHO-R3 cells were transfected with empty vector (mock), WT-, or DN-PLD1 and -PLD2 where indicated. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were treated with 100 nm PTH(1–34) for 15 min. After incubation, the cells were scraped in Laemmli buffer. Extracted proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Phosphorylated ERK (pERK) and total ERK were determined by immunoblotting (IB). A, Representative blot; B, summary of results obtained from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 for the depicted comparisons.

Finally, the details of how PTH activates PLD remain incompletely understood. A mechanism mediated by G12/13 and RhoA has been proposed to be responsible for the activation of PLD in UMR-106 cells (27). This scheme, however, is somewhat paradoxical because stimulation of cells with PTH leads to the accumulation of cAMP, which in turn inhibits RhoA activity by direct phosphorylation (58). This effect has been linked to inhibition of PLD in neutrophils (59) and to overall cytoskeletal reorganization (58,60). Thus, it remains unclear how PTH induces RhoA activation in a cAMP background. GPCR may activate PLD function by several other mechanisms. These include activation of small GTPases of the ARF family (61), or formation of macromolecular complexes that include PLD2 and the small GTPase Ral (37). Some GPCR, such as the μ-opioid receptor, interact directly with PLD2, although the regulation of PLD activity by this assembly still requires the activation of ARF GTPases (13). The potential role of these alternative mechanisms on PTH-dependent PLD activation remains to be explored.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and transfection

ROS 17/2.8 cells were grown in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution at 37 C, 5% CO2.

Chinese hamster ovary cells stable expressing HA-tagged human PTH1R, CHO-N10-R3, were maintained in Ham’s F-12 medium (Mediatech Inc., Herndon, VA) with 10% fetal bovine serum. Transient transfection was performed using FUGENE 6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All experiments were performed 48 h after transfection.

Plasmids encoding scrambled shRNA, rat PLD1 shRNA, and rat PLD2 shRNA were described previously (19). The sequences used to silence PLD1 and PLD2 were 547CTGGAAGAT TACTTGACAA (for PLD1) and 723GGACTCC TTCCTGCTGTACA (for PLD2). PLD2 rescue experiments were performed using a mouse EGFP-PLD2 construct with a single nucleotide substitution (730T→A). Expression of the rescue construct was verified measuring EGFP fluorescence. ROS cells stably expressing each shRNA were selected using 500 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen).

PLD mutants

WT and catalytically inactive variants of PLD1 and PLD2 (K898R-PLD1 and K758R-PLD2) were previously described (14,15) and fused to green fluorescent protein by subcloning into pEFGP-C1. Transfection efficiency was estimated from fluorescence microscopy data by determining the fraction of cells expressing the green fluorescent constructs. Transfection efficiency was better than 30% in all experiments.

PLD assays

Cells cultivated in six-well plates at 75% confluence were serum starved and labeled overnight with [3H]palmitate (5 mCi/ml) in culture medium containing 0.1% BSA. Cells were stimulated with PTH(1–34) (100 nm) in the presence of 0.5% ethanol for the indicated times. At the end of the incubation, the cells were scraped and transferred to Eppendorf tubes, and the reaction was stopped by addition of chloroform/methanol (1:1). The lipid phase was extracted and developed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel 60 plates using ethyl acetate/trimethylpentane/acetic acid (9:5:2) as solvent. The position of major phospholipids was determined using standards (Avanti Biochemicals, Birmingham, AL) and autoradiography. The TLC plates were developed by autoradiography, and the radioactivity associated with each band was estimated by densitometry and quantified using ImageJ. In some cases, the TLC plates were scraped, and the total amount of radioactivity associated with each lipid species was determined by liquid scintillation counting. The data are expressed as band intensity/number of counts associated with the phosphatidylethanol spot normalized by total intensity/number of counts of lipid loaded.

RT-PCR

Quantification of PLD mRNA was conducted as previously described (35). Briefly, total cellular RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen) and transcribed into cDNA using a Clontech (Palo Alto, CA) Advantage RT-for-PCR kit. The resulting cDNA was used to amplify PLD1, PLD2, and GAPDH as described previously (35). PCR products were resolved using a 1.5% agarose gel, digitally photographed, and measured using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on an Applied BioSystems (Foster City, CA) StepOne real-time PCR system using SYBR Green (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) with the primers previously described. Negative control wells containing nuclease-free water instead of cDNA were used to check for amplicon contamination. All samples were run in duplicate and normalized using GAPDH. A standard curve was generated using 10-fold dilutions of EGFP-PLD1 and EGFP-PLD2 plasmid. Both standard curves had a correlation coefficient greater than 0.98. Total copy number of each target was extrapolated from the standard curve. Copy number per cell was calculated by dividing the total copy number by the cell count and adjusting for transfection efficiency.

Immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy

Cells were cultured on glass coverslips, transfected with the desired plasmids, and allowed to grow until 80% confluent. The coverslips were washed in PBS and fixed for 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. The samples were blocked with 3% BSA in PBS and then stained with either anti-HA, anti-EEA1, or anti ARF1 antibodies in 1% BSA in PBS for 2 h at room temperature. The samples were washed three times with PBS and incubated with respective secondary antibody (antimouse IgG or antirabbit IgG conjugated with either tetraethylrhodamine or fluorescein isothiocyanate). The cells were then washed with PBS (3×), mounted with gelvatol, and examined. An Olympus Fluoview 1000 confocal microscope was used for all experiments.

FACS

CHO-R3 cells were transiently transfected with EGFP fusion constructs of WT-PLD1, DN-PLD1, WT-PLD2, and DN-PLD2, as described above, using Fugene6. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were switched to serum-free F-12 medium and stimulated with PTH(1–34) (100 nm) for 0, 10, or 30 min. After incubation, the cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and fixed with 0.5% p-formaldehyde in PBS for 5 min at 4 C. The cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 3% BSA in PBS for 30 min to block nonspecific antibody binding. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with rabbit anti-HA antibody [Covance (Madison, WI) HA.11, 1:200] and antirabbit-Alexa-680 (Invitrogen; 1:500) for 1.5 h at room temperature, respectively. Finally, cells were scraped and analyzed by FACS. EGFP/cherryFP fluorescence was used to gate cells transfected with the PLD or shRNA constructs.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA followed by column statistic comparisons using the analysis routines built in GraphPad Prism. Quantitative image analyses were performed using ImageJ. Colocalization analyses were done using the ImageJ built-in plug-ins for Pearson correlation. The Pearson correlation coefficient is defined as the ratio of the covariance of the red and green color images divided by the product of the sd of the normalized image intensities. Differences with P ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Footnotes

This work was supported by DK-54171 from the National Institutes of Health (to P.A.F.) and by a grant from the Office of the senior Vice Chancellor for the Health Sciences of the University of Pittsburgh (to G.R.). D.W. was supported by Training Grants GM-08424 and DK-083211.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online October 16, 2009

Abbreviations: ARF1, ADP ribosylation factor-1; DN, dominant negative; EEA1, early endosome antigen 1; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; HA, hemagglutinin; PA, phosphatidic acid; PLD, phospholipase D; PTH1R, PTH type 1 receptor; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; TLC, thin-layer chromatography; WT, wild type.

References

- Abou-Samra AB, Jüppner H, Force T, Freeman MW, Kong XF, Schipani E, Urena P, Richards J, Bonventre JV, Potts Jr JT, Kronenberg HM, Segre GV 1992 Expression cloning of a common receptor for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide from rat osteoblast-like cells: a single receptor stimulates intracellular accumulation of both cAMP and inositol trisphosphates and increases intracellular free calcium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:2732–2736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offermanns S, Iida-Klein A, Segre GV, Simon MI 1996 Gαq family members couple parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related peptide and calcitonin receptors to phospholipase C in COS-7 cells. Mol Endocrinol 10:566–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman PA, Gesek FA, Morley P, Whitfield JF, Willick GE 1999 Cell-specific signaling and structure-activity relations of parathyroid hormone analogs in mouse kidney cells. Endocrinology 140:301–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari SL, Behar V, Chorev M, Rosenblatt M, Bisello A 1999 Endocytosis of ligand-human parathyroid hormone receptor 1 complexes is protein kinase C-dependent and involves β-arrestin2. Real-time monitoring by fluorescence microscopy. J Biol Chem 274:29968–29975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon WB, Magyar CE, Willick GE, Syme CA, Galbiati F, Bisello A, Friedman PA 2004 Ligand-selective dissociation of activation and internalization of the parathyroid hormone (PTH) receptor: conditional efficacy of PTH peptide fragments. Endocrinology 145:2815–2823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilardaga JP, Krasel C, Chauvin S, Bambino T, Lohse MJ, Nissenson RA 2002 Internalization determinants of the parathyroid hormone receptor differentially regulate β-arrestin/receptor association. J Biol Chem 277:8121–8129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler D, Sneddon WB, Wang B, Friedman PA, Romero G 2007 NHERF-1 and the cytoskeleton regulate the traffic and membrane dynamics of G protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem 282:25076–25087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Camilli P, Emr SD, McPherson PS, Novick P 1996 Phosphoinositides as regulators in membrane traffic. Science 271:1533–1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth MG 1999 Lipid regulators of membrane traffic through the Golgi complex. Trends Cell Biol 9:174–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SM, Altshuller YM, Sung TC, Rudge SA, Rose K, Engebrecht J, Morris AJ, Frohman MA 1995 Human ADP-ribosylation factor-activated phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase D defines a new and highly conserved gene family. J Biol Chem 270:29640–29643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AJ, Engebrecht J, Frohman MA 1996 Structure and regulation of phospholipase D. Trends Pharmacol Sci 17:182–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam Y, Exton JH 2001 Phospholipase D activity is required for actin stress fiber formation in fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol 21:4055–4066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch T, Brandenburg LO, Schulz S, Liang Y, Klein J, Hollt V 2003 ADP-ribosylation factor-dependent phospholipase D2 activation is required for agonist-induced μ-opioid receptor endocytosis. J Biol Chem 278:9979–9985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MA, Shome K, Vasudevan C, Stolz DB, Sung TC, Frohman MA, Watkins SC, Romero G 1999 Phospholipase D and its product, phosphatidic acid, mediate agonist-dependent raf-1 translocation to the plasma membrane and the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Biol Chem 274:1131–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MA, Shome K, Watkins SC, Romero G 2000 The recruitment of Raf-1 to membranes is mediated by direct interaction with phosphatidic acid and is independent of association with Ras. J Biol Chem 275:23911–23918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colley WC, Sung TC, Roll R, Jenco J, Hammond SM, Altshuller Y, Bar-Sagi D, Morris AJ, Frohman MA 1997 Phospholipase D2, a distinct phospholipase D isoform with novel regulatory properties that provokes cytoskeletal reorganization. Curr Biol 7:191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs TC, Meier KE 2000 Expression and regulation of phospholipase D isoforms in mammalian cell lines. J Cell Physiol 182:77–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier KE, Gibbs TC, Knoepp SM, Ella KM 1999 Expression of phospholipase D isoforms in mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1439:199–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du G, Huang P, Liang BT, Frohman MA 2004 Phospholipase D2 localizes to the plasma membrane and regulates angiotensin II receptor endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell 15:1024–1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arneson LS, Kunz J, Anderson RA, Traub LM 1999 Coupled inositide phosphorylation and phospholipase D activation initiates clathrin-coat assembly on lysosomes. J Biol Chem 274:17794–17805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch T, Brandenburg LO, Liang Y, Schulz S, Beyer A, Schröder H, Höllt V 2004 Phospholipase D2 modulates agonist-induced μ-opioid receptor desensitization and resensitization. J Neurochem 88:680–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman N, Ledford B, Di Fulvio M, Frondorf K, McPhail LC, Gomez-Cambronero J 2007 Phospholipase D2-derived phosphatidic acid binds to and activates ribosomal p70 S6 kinase independently of mTOR. FASEB J 21:1075–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Du G, Skowronek K, Frohman MA, Bar-Sagi D 2007 Phospholipase D2-generated phosphatidic acid couples EGFR stimulation to Ras activation by Sos. Nat Cell Biol 9:706–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Xu L, Foster DA 2001 Role for phospholipase D in receptor-mediated endocytosis. Mol Cell Biol 21:595–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrotte M, Chasserot-Golaz S, Huang P, Du G, Ktistakis NT, Frohman MA, Vitale N, Bader MF, Grant NJ 2006 Dynamics and function of phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid during phagocytosis. Traffic 7:365–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer SS, Barton JA, Bourgoin S, Kusner DJ 2004 Phospholipases D1 and D2 coordinately regulate macrophage phagocytosis. J Immunol 173:2615–2623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AT, Gilchrist A, Voyno-Yasenetskaya T, Radeff-Huang JM, Stern PH 2005 Gα12/Gα13 subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins mediate parathyroid hormone activation of phospholipase D in UMR-106 osteoblastic cells. Endocrinology 146:2171–2175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda K, Nogami M, Murakami K, Kanaho Y, Nakayama K 1999 Colocalization of phospholipase D1 and GTP-binding-defective mutant of ADP-ribosylation factor 6 to endosomes and lysosomes. FEBS Lett 442:221–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du G, Altshuller YM, Vitale N, Huang P, Chasserot-Golaz S, Morris AJ, Bader MF, Frohman MA 2003 Regulation of phospholipase D1 subcellular cycling through coordination of multiple membrane association motifs. J Cell Biol 162:305–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucocq J, Manifava M, Bi K, Roth MG, Ktistakis NT 2001 Immunolocalisation of phospholipase D1 on tubular vesicular membranes of endocytic and secretory origin. Eur J Cell Biol 80:508–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Bisello A, Yang Y, Romero GG, Friedman PA 2007 NHERF1 regulates parathyroid hormone receptor membrane retention without affecting recycling. J Biol Chem 282:36214–36222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto I, Shigeno C, Potts Jr JT, Segre GV 1988 Characterization and agonist-induced down-regulation of parathyroid hormone receptors in clonal rat osteosarcoma cells. Endocrinology 122:1208–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen BT, Rizzo MA, Shome K, Romero G 2002 The role of phosphatidic acid in the regulation of the Ras/MEK/Erk signaling cascade. FEBS Lett 531:65–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo M, Romero G 2002 Pharmacological importance of phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid in the regulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Pharmacol Ther 94:35–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen BT, Jackson EK, Romero GG 2001 Angiotensin II signaling to phospholipase D in renal microvascular smooth muscle cells in SHR. Hypertension 37:635–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shome K, Rizzo MA, Vasudevan C, Andresen B, Romero G 2000 The activation of phospholipase D by endothelin-1, angiotensin II, and platelet-derived growth factor in vascular smooth muscle A10 cells is mediated by small G proteins of the ADP-ribosylation factor family. Endocrinology 141:2200–2208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya M, Babwah AV, Godin C, Anborgh PH, Dale LB, Poulter MO, Ferguson SS 2004 Ral and phospholipase D2-dependent pathway for constitutive metabotropic glutamate receptor endocytosis. J Neurosci 24:8752–8761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Park IH, Wu AL, Du G, Huang P, Frohman MA, Walker SJ, Brown HA, Chen J 2003 PLD1 regulates mTOR signaling and mediates Cdc42 activation of S6K1. Curr Biol 13:2037–2044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen BT, Romero GG, Jackson EK 2004 AT2 receptors attenuate AT1 receptor-induced phospholipase D activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 309:425–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen BT, Shome K, Jackson EK, Romero GG 2005 AT2 receptors cross talk with AT1 receptors through a nitric oxide- and RhoA-dependent mechanism resulting in decreased phospholipase D activity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288:F763–F770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Asico LD, Yu P, Wang Z, Jones JE, Bai RK, Sibley DR, Felder RA, Jose PA 2005 D5 dopamine receptor regulation of phospholipase D. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288:H55–H61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SM, Jenco JM, Nakashima S, Cadwallader K, Gu Q, Cook S, Nozawa Y, Prestwich GD, Frohman MA, Morris AJ 1997 Characterization of two alternately spliced forms of phospholipase D1. Activation of the purified enzymes by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, ADP-ribosylation factor, and Rho family monomeric GTP-binding proteins and protein kinase C-α. J Biol Chem 272:3860–3868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeniou-Meyer M, Zabari N, Ashery U, Chasserot-Golaz S, Haeberlé AM, Demais V, Bailly Y, Gottfried I, Nakanishi H, Neiman AM, Du G, Frohman MA, Bader MF, Vitale N 2007 Phospholipase D1 production of phosphatidic acid at the plasma membrane promotes exocytosis of large dense-core granules at a late stage. J Biol Chem 282:21746–21757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L, Stope MB, de Jesús ML, Oude Weernink PA, Urban M, Wieland T, Rosskopf D, Mizuno K, Jakobs KH, Schmidt M 2007 Direct stimulation of receptor-controlled phospholipase D1 by phospho-cofilin. Embo J 26:4189–4202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon MJ, Segre GV 2004 Stimulation by parathyroid hormone of a NHERF-1-assembled complex consisting of the parathyroid hormone I receptor, phospholipase Cβ, and actin increases intracellular calcium in opossum kidney cells. J Biol Chem 279:23550–23558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon WB, Syme CA, Bisello A, Magyar CE, Rochdi MD, Parent JL, Weinman EJ, Abou-Samra AB, Friedman PA 2003 Activation-independent parathyroid hormone receptor internalization is regulated by NHERF1 (EBP50). J Biol Chem 278:43787–43796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon MJ, Donowitz M, Yun CC, Segre GV 2002 Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor 2 directs parathyroid hormone 1 receptor signalling. Nature 417:858–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daaka Y, Luttrell LM, Ahn S, Della Rocca GJ, Ferguson SS, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ 1998 Essential role for G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis in the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 273:685–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce KL, Maudsley S, Daaka Y, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ 2000 Role of endocytosis in the activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase cascade by sequestering and nonsequestering G protein-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:1489–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn S, Nelson CD, Garrison TR, Miller WE, Lefkowitz RJ 2003 Desensitization, internalization, and signaling functions of β-arrestins demonstrated by RNA interference. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:1740–1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon WB, Liu F, Gesek FA, Friedman PA 2000 Obligate mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in parathyroid hormone stimulation of calcium transport but not calcium signaling. Endocrinology 141:4185–4193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz RJ, Whalen EJ 2004 β-Arrestins: traffic cops of cell signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol 16:162–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesbert F, Sauvonnet N, Dautry-Varsat A 2004 Clathrin-independent endocytosis and signalling of interleukin 2 receptors IL-2R endocytosis and signalling. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 286: 119–148 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Lai CF, Mobley WC 2001 Nerve growth factor activates persistent Rap1 signaling in endosomes. J Neurosci 21:5406–5416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin E, Sorkin A 2008 Endosomal targeting of MEK2 requires RAF, MEK kinase activity and clathrin-dependent endocytosis. Traffic 9:1776–1790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L, Lucocq J 1998 ERK2 signalling from internalised epidermal growth factor receptor in broken A431 cells. Cell Signal 10:339–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft CA, Garrido JL, Fluharty E, Leiva-Vega L, Romero G 2008 Role of phosphatidic acid in the coupling of the ERK cascade. J Biol Chem 283:36636–36645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang P, Gesbert F, Delespine-Carmagnat M, Stancou R, Pouchelet M, Bertoglio J 1996 Protein kinase A phosphorylation of RhoA mediates the morphological and functional effects of cyclic AMP in cytotoxic lymphocytes. EMBO J 15:510–519 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak JY, Uhlinger DJ 2000 Downregulation of phospholipase D by protein kinase A in a cell-free system of human neutrophils. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 267:305–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan JJ, Gronowicz G, Rodan GA 1991 Parathyroid hormone promotes the disassembly of cytoskeletal actin and myosin in cultured osteoblastic cells: mediation by cyclic AMP. J Cell Biochem 45:101–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R, Robertson DN, Holland PJ, Collins D, Lutz EM, Johnson MS 2003 ADP-ribosylation factor-dependent phospholipase D activation by the M3 muscarinic receptor. J Biol Chem 278:33818–33830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]