Abstract

Background

Parenting stresses have consistently been found to be higher in parents of children with intellectual disabilities (ID); yet, some families are able to be resilient and thrive in the face of these challenges. Despite the considerable research on stress in families of ID, there is still little known about the stability and compensatory factors associated with everyday parenting stresses.

Methods

Trajectories of daily parenting stress were studied for both mothers and fathers of children with ID across child ages 36–60 months, as were specific familial risk and resilience factors that affect these trajectories, including psychological well-being of each parent, marital adjustment and positive parent–child relationships.

Results

Mothers’ daily parenting stress significantly increased over time, while fathers’ daily parenting stress remained more constant. Decreases in mothers’ daily parenting stress trajectory were associated with both mother and father’s well-being and perceived marital adjustment, as well as a positive father–child relationship. However, decreases in fathers’ daily parenting stress trajectory were only affected by mother’s well-being and both parents’ perceived marital adjustment.

Conclusions

Parenting stress processes are not shared entirely across the preschool period in parents of children with ID. Although individual parent characteristics and high-quality dyadic relationships contribute to emerging resilience in parents of children with ID, parents also affect each others’ more resilient adaptations in ways that have not been previously considered.

Keywords: fathers, intellectual disability, mothers, parenting stress, resilience

Introduction

Historically, a child’s diagnosis of an intellectual disability (ID) was considered a traumatic experience for families (Wolfensberger & Menolascino 1970; Blacher et al. 2002). Subsequent to the diagnosis, parents were thought to take a more negative view towards their child, and face increased stress with regard to their upbringing and future (Kanner 1953). A wealth of research continues to suggest that families of children with ID face increased stressors (Blacher et al. 2005). Indeed, levels of stress have been found to be higher in parents of children with ID than in their typically developing counterparts (Hauser-Cram et al. 2001), perhaps due to frequent comorbid behaviour problems (Baker et al. 2003). Despite these greater stresses, it is apparent that certain parents and families are well adapted and appear resilient in the face of the challenges apparent. But given the diversity in adaptations seen in families of children with ID, there is a need to identify those factors and processes that lead to more resilient outcomes while other parents become increasingly stressed over time.

It has been previously suggested that family adaptation may be based on the interplay of experienced stress, available coping resources, and ecological contexts in which the individual family must operate (Crnic et al. 1983). Other conceptualisations have focused more directly on factors that may lead to the perceived stress in families of children with ID, suggesting that child characteristics, social support, personal and family system resources, and other life stressors may play an important role (Heiman 2002; Perry 2005; Blacher & Baker 2007; Pottie & Ingram 2008). With notables exceptions (e.g. Hauser-Cram et al. 2001), few longitudinal studies exist that explore the complex developmental processes detailing risk and resilience in families of children with ID. Thus, the overall aim of the current study is to examine the trajectories of daily parenting stress in families of children with ID, and explore specific risk and compensatory factors that lead to more resilient patterns in these parents.

Daily parenting stress

Stress has long been identified as an important determinant of family functioning and family relationships. Although many facets of stress have been associated with parenting and child development, including life stress (Crnic et al. 2005) and financial strain (Conger et al. 1992), stress specific to parenting is a particularly salient issue for families. Parenting stress has been conceptualised from multiple perspectives, but often targets the everyday challenges and demands of caregiving (Crnic & Low 2002). Deater-Deckard (2005) has suggested that such daily parenting stresses play a critically important role in the development of parenting and subsequently, in children’s psychological and developmental well-being.

Considerable attention has been paid to the increased stress levels of families raising a child with ID (Crnic et al. 1983; Orr et al. 1993; Baker et al. 1997, 2003, Fidler et al. 2000). Beyond the stress of the diagnosis and adjustment, families experience increased caregiving demands (Crnic et al. 1983), additional financial strain (Gunn & Berry 1987; Parish et al. 2004) and attitudes of professionals and schools in their reaction to the child (Blacher & Hatton 2007). Across this literature, stress has been examined in terms of major life change (Sarason et al. 1978), stresses specifically associated with having a child with ID (Friedrich et al. 1983) and the impact on the family as a result of having a child with ID (Donenberg & Baker 1993). But the experience of stress varies as a function of individual appraisal, and differences exist both between and within families. In general, there is ample reason to expect that stress may affect mothers and fathers differently (Crnic & Booth 1991; Creasey & Reese 1996; McDonald & Almeida 2004), and Herring et al. (2006) found that on average, fathers of children with ID report less stress than do mothers, although findings on the effects of parent gender have proven complex (Gray 2003; Hastings 2003). Although the research to date has been informative regarding family stress, few studies of families of children with ID have focused specifically on the stress perceived by parents as result of parenting. For these families, examining the everyday stressors and hassles associated with rearing a child with ID may be particularly salient (Crnic & Low 2002). Furthermore, although the evidence is clear that parents of children with ID face greater levels of parenting stress (Fidler et al. 2000; Hauser-Cram et al. 2001; Baker et al. 2002), little is known about stress over time, the trajectory of parents’ stressful experience or the factors that may influence these trajectories.

Factors affecting the experience of daily parenting stress

Within the developmental literature, parental resilience in the face of stressful experience has been much discussed (Luthar 2007). Nonetheless, we have only incremental knowledge of those factors that might predict parental and family response to stress. This is especially true in relation to families with a child with ID, and it is important to explicate those factors that play a compensatory role, and are associated with greater resilience in these families.

It has been well argued that resilience is not a trait, nor should it be considered an adjective to describe an individual (Luthar & Zelazo 2003); it is more a process that involves contextual elements, the population of interest, the specific risk involved, the promotive factors and the outcomes (Fergus & Zimmerman 2005). Much of the work identifying resilience processes has involved the study of either compensatory or protective processes. Models of compensatory process involve a direct effect of some promotive factor on an outcome; Fergus & Zimmerman (2005) define a compensatory model of resilience to be one in which a ‘promotive factor counteracts or operates in an opposite direction of a risk factor (p. 491)’. In contrast, models of protective processes operate to moderate or reduce the effects of a risk on some negative outcome (Luthar et al. 2000; Fergus & Zimmerman 2005).

A number of factors have been addressed in the literature as potentially compensatory, from both individual and familial perspectives (Luthar 2003). Among this universe of potential compensatory factors, we contend that three may be particularly salient and adaptive: parental psychological well-being or health, a supportive partner or intimate relationship and a positive parent–child relationship. Parental well-being and supportive partnerships have shown some merit as possible compensatory factors in previous research, although the presence of an established positive parent–child relationship has to date rarely been considered as a predictor of more positive adaptations.

Parental well-being

Research has consistently shown associations between parental symptomatology and everyday parenting hassles (Crnic & Low 2002) and also been indicated as a predictor of parenting stress (Chang & Fine 2007; Williford et al. 2007). For parents of children with ID, psychological distress may be a particularly important risk factor and well-being a compensatory one. Parents of children with ID report high levels of symptomatology (Emerson et al. 2004; Feldman et al. 2007), often higher than parents of typically developing children (Olsson & Hwang 2001; Herring et al. 2006). Although symptomatology and well-being are not identical constructs, absence of symptomatology has previously been used as a proxy for well-being in research on families of children with ID (Baker et al. 2005; Eisenhower et al. 2005; Kersh et al. 2006). As parents of children with ID are at greater risk for increased symtomatology, the absence of such distress may be considered resilient and a characteristic of well-being in these families (Fergus & Zimmerman 2005). Thus, the parents with better well-being and who can maintain a more positive mental health status may be better able to better cope with stressful demands of caregiving.

Marital quality

The resilience literature has suggested that having a supportive person in one’s life is an important factor in resilience (Luthar 2007), and other research has found that a high-quality marriage may be compensatory for families with psychological distress (Davies & Cummings 2006). Recent research has found that having a good relationship with an intimate partner is associated with decreases in parenting stress (Mulsow et al. 2002), while single parenthood predicts greater levels of parenting stress (Williford et al. 2007). For couples of children with ID, a meta-analysis revealed that there is a small but significant decrease in marital satisfaction (Risdal & Singer 2004). However, greater marital quality in these couples has also predicted lower parenting stress, even after considering the influence of socioeconomic status, child characteristics and other measures of social support (Kersh et al. 2006). A supportive partner likely shares the burden of caregiving better, perhaps compensating for the generally high levels of parenting stress in these families.

Parent–child relationship quality

Although not often considered a moderator or a protective factor, the quality of the parent–child relationship may also be an important compensatory predictor of daily parenting stress. Parent–child relationships in families of children with ID tend to be more directive, although this directiveness does not indicate that these parents are less affectionate, positive or warm (Marfo 1990; Roach et al. 1998). In fact, research tends to suggest that the role of parent–child relationships operate similarly for typically developing children and children with ID (Guralnick et al. 2007). Further, a positive parent–child relationship has consistently been shown to be associated with positive child outcomes in typically developing children as well as children with ID (Mink et al. 1983; Hauser-Cram et al. 1999; Spiker et al. 2002). Although parenting hassles have been associated with decreases in the quality of family relationships (Crnic & Greenberg 1990), transactional influences of the parent–child relationship on daily parenting stresses is less well-known. Such processes are conceptually important to stress and family adaptation (Crnic et al. 1983), wherein a positive parent–child relationship may facilitate better functioning across a range of possible adaptive outcomes, including lower stress.

Cross-parent risk

The true complexity of families suggests that influences are likely to be much more complicated than the pervasive within-parent models suggest. Indeed, aspects of fathers’ functioning may well affect mothers’ daily stress, and in turn, aspects of mothers’ functioning may affect fathers’ experience of stress. Such crossover effects have been examined in the family-work literature to inconclusive findings (Perry-Jenkins et al. 2000). Crouter et al. (1999) found that when the husband feels greater stress at work, the wife experiences greater symptoms of depression. However, the wife’s pressure at work did not result in significant increases in symptomatology for the husband. Other studies have also found mixed support for crossover effects stress literature (Wortman et al. 1991; Stewart & Barling 1996). In families with a child with ID, prior research has indicated some support for cross-parent effects in that parental stress was affected by the opposite partner’s symptomatology, particularly for fathers (Hastings 2003; Hastings et al. 2005). Still, very little is still known as to how crossover effects affect the experience of daily parenting stresses in populations in which stresses are known to be more frequent. The extent to which there may be crossover predictions of parenting stress, and the degree to which certain predictors may be more salient for one parent merit much further attention in developing models of family stress experience.

The present study

Given the increased focus on resilience in the literature, as well as the relation between daily parenting stress and ID, this study addresses two major questions for parents of ID. First, this study examines the trajectories of daily parenting stress for mothers and fathers of children with ID, considering both the absolute and relative stability over time by identifying growth curves for both parents. Second, the study addresses three specific risk and compensatory factors may affect these trajectories of daily parenting stress: parental well-being, marital adjustment and a positive parent–child relationship. Each factor is explored for its effect on the daily parenting stresses of the same parent, as well as the crossover effects on the opposite parent’s perception of daily parenting stress.

Methods

Participants

The participants were 115 families of 3-year-old children with ID. Participants in the study were part of a longitudinal study of families of both typically developing children and children with ID who had been recruited to participate from child ages 36 to 60 months. One-fourth of these families were from a rural/suburban community Central Pennsylvania and three-fourths were from Southern California. The children with ID were primarily recruited from community agencies serving families of children with ID. The selection criteria for the study were (1) child ages between 30 and 40 months; (2) a score on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development II (BSID II; Bayley 1993 – see below) between 30 and 85; (3) child must be ambulatory; and (4) no diagnosis of autism.

The children in the study had an average Mental Developmental Index (MDI) score of 59.97, with a standard deviation of 12.71, and 66.1% of the children were male. On average, both parents completed some college, and the median number of years of college for each parent was 14 years. The median income level for families was between $35 000 and $50 000. Overall, 58.3% of mothers identified as Caucasian, while 57.4% of fathers identified as Caucasian.

Overall, 23 subjects dropped out of the study by 60 months. This is an attrition rate of 20% over 2 years. No differences between families who dropped out and those who remained were found among any study or demographic variables.

Procedures

Prior to the initial appointment, parents completed a telephone intake interview and received project descriptions and an informed consent procedure. At the initial appointment, two trained research assistants visited the family and obtained demographic information and administered the BSID II to assess the developmental level of the child. At the time of the initial assessment, both the mother and father were given a booklet of questionnaires to complete, which were returned by mail. Measures of psychological well-being and marital adjustment were included in these booklets.

Naturalistic home observations were also conducted every 6 months from child ages 36 to 60 months. These home observations were scheduled at times when the entire family would be present, which most often occurred in the early evening. At the beginning of each visit, both parents rated their daily parenting hassles (see below). Once the hassles scale was completed, the observational sessions began. Families were asked to behave as they normally would, and observers attempted to stay in the background but followed the child as a central observational focus of the home-based interactions. The observers collected information over discrete periods of coding, with each period lasting 10 min. Following a 10-min observational episode, a 5-min period rating period ensued in which the observers rated various codes of parent, child and dyadic behaviour. All observers were trained by watching videotaped home observation and attending live home observations with an experienced observer/coder until reliability was established. Training reliability criteria were set as a minimum of 70% exact agreement and 95% agreement within one scale point of the criterion coder. To maintain reliability within and across sites, reliability between coders was maintained at kappa = 0.6 or higher.

Measures

Developmental level

Developmental level was determined by using the BSID-II (Bayley 1993); a widely used measure of mental and motor development for child ages 1–42 months. It was administered in the home with the mother present. Only the MDI of the BSID-II was given. The MDI is normed with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. Bayley (1993) has reported high test–retest reliability with the MDI (r = 0.91).

Daily parenting stress

Daily parenting stress (or parenting hassles) was assessed with the parenting daily hassles (PDH) measure (Crnic & Greenberg 1990). As noted, each parent independently completed the hassles measure at the beginning of each home observation. The PDH consists of 20 specific items related to child behaviours and parenting tasks that can be trying or challenging for parents. Using 5-point scales for each item, the parent was asked to rate both how often the hassle occurred and how much of a hassle the item was perceived to be. Examples of items include being whined at or being complained to, difficulty getting privacy, sibling fighting requires a referee and having to change plans because of unplanned child need. Two summary scores were created: the frequency of parenting hassles and the perceived intensity of those hassles. The intensity score is an index of appraised stress-fulness by the parent, whereas the frequency reflects only the presence of stressors. Prior research has indicated that individual cognitive appraisal of significant events as stressful is the primary factor that predicts the impact of a stressor (Lazarus et al. 1985). Thus, the perceived intensity of hassles at each year was used in the study. Adequate reliability and validity for this measured has been previously reported (Crnic & Greenberg 1990).

Parental well-being

Well-being was measured using the Symptom Checklist-35 (SCL; Derogatis 1993), a widely used measured of symptomatology and parent well-being. The SCL-35 is a short-form of the SCL-90 and the Brief Symptom Inventory. Adequate reliability for this measure (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84) has been previously reported (Cicirelli 2000). Higher scores on the SCL-35 reflect more psychological symptoms, and lower scores are indicative of greater well-being.

Marital adjustment

Marital adjustment was measured with the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Spanier 1976, 1979). As with the SCL, each parent separately completed the DAS at 36 months and returned the booklet via mail. The DAS has four sub-scales: affection, cohesion, conflict and satisfaction. The total summary score of marital adjustment for each parent was used for analysis. Adequate reliability for this measure (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96) has been previously reported (Spanier 1976).

Parent–child interaction

Data for positive parent–child interactions were obtained using the Parent Child Interaction Rating Scale (PCIRS; Belsky et al. 1995). Although the PCIRS includes categories of individual parent and child behavioural qualities, only ratings of dyadic quality were of interest in this study. Further, given the focus on resilience and compensatory factors, our specific focus was on indices of parent–child pleasure in interaction. As described above, the ratings of dyadic parent–child pleasure were made after each of six 10-min observational coding periods. Dyadic pleasure was rated on a scale of 1 (low) to 5 (high), and was defined as the extent of mutual enjoyment evidenced by both the parent and child across the interaction episode. Dyadic pleasure scores were obtained for both parents and averaged across all coding periods. As reported earlier, reliability was maintained at kappa = 0.6 or above. Only those parent–child dyadic pleasure ratings obtained at 36 months were used in this study.

Data analytic plan

Latent growth structural equation modelling using Mplus version 4.1 (Muthén & Muthén 2005) were used to test the hypotheses regarding PDH over time and risk and resilience factors that may predict daily parenting stress trajectories. Singer & Willett (2003) suggest that growth modelling is better able to capitalise on the richness of longitudinal data than are other methods because it can more accurately measure and model rates of change. Growth modelling allows for examination of both the trajectory of parenting stress as well as the level of stress at any particular timepoint. Recently, Burchinal et al. (2006) argued that latent growth curves are preferable to univariate and multivariate repeated measures because latent growth curves are able to assess measurement error in the predictors as well as the slope.

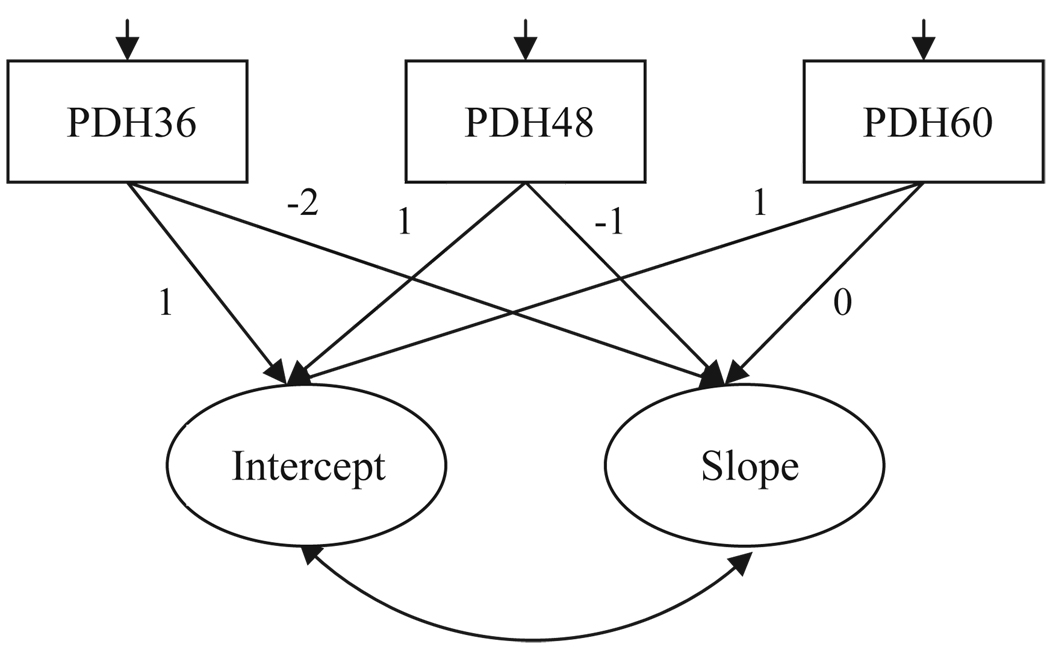

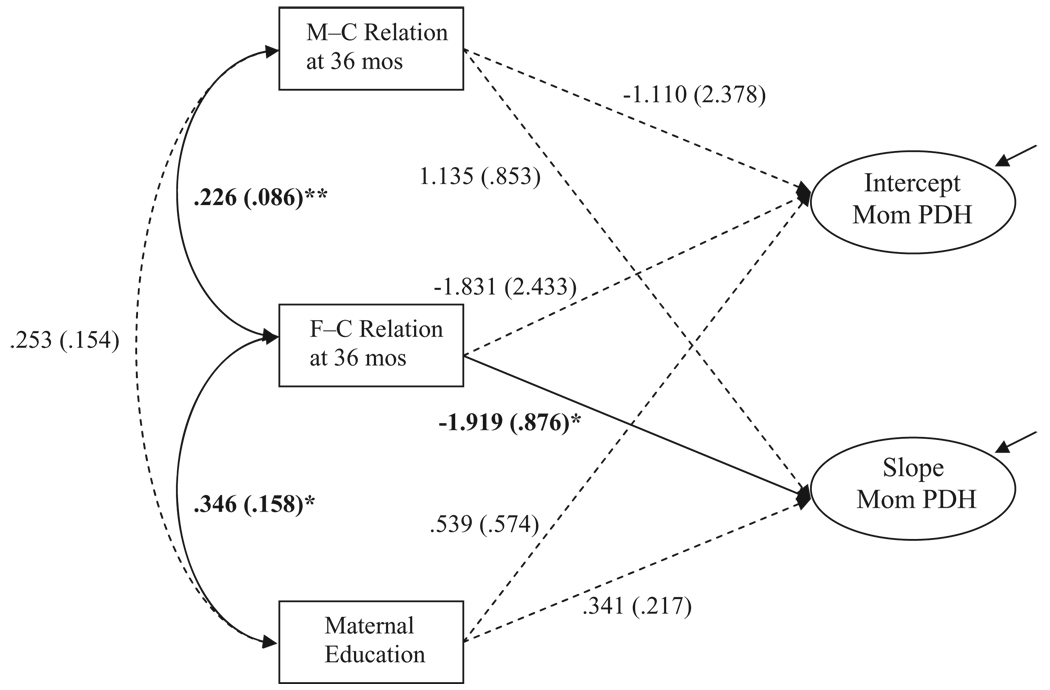

In this study, growth models were estimated separately for mothers’ and fathers’ PDH, because of potential multicolinearity among variables. Linear growth models estimate two latent factors, one representing the level of PDH at a given timepoint (i.e. the intercept) and one representing the change in PDH over time (i.e. the slope) (Duncan et al. 1999). Analyses used the self-reported PDH score at child ages 36, 48 and 60 months (see Fig. 1 for analysis model). In all analyses, the intercept was set so that time was centred at 60 months.

Figure 1.

Analysis model of parenting daily hassles (PDH) growth curve.

As there was attrition in the study that was not accounted for by any demographic or study variables, models were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation with full information maximum likelihood. This method has been shown to properly account for missing data well under these circumstances (Enders & Bandalos 2001).

Predictors of PDH were all measured at 36 months and centred at their mean value. Analyses controlled for maternal education in models of mothers’ PDH, and controlled for paternal education in models of fathers’ PDH. Four models were run for each parent; one for parent symptoms, two for marital adjustment and one for parent–child relationship. Two models of marital adjustment were run because of the high correlation between mother-reported marital adjustment and father-reported marital adjustment (r = 0.684). The parent–child relationship factors indicated some skewness, so in analyses involving parent–child relationship, estimation was made using the Satorra-Bentler method (ML Robust; Satorra & Bentler 1994). This method gives more accurate parameter estimates, but its chi-square needs to be recalculated using a correction factor to account for skew. Reported chi-squares in these analyses use the corrected chi-square statistic.

Results

Descriptives

Descriptive statistics are reported for all variables in the model (see Table 1). Reliability was sufficient for all scales used, ranging from Cronbach’s α = 0.822 to α = 0.908 (see Table 1). Paired-sample t-tests were used to calculate differences in the means of all variables for both parents, and results indicated that mothers reported significantly higher levels of PDH than did fathers at 48 and 60 months, respectively, t(80) = 3.366, P = 0.001, t(72) = 3.462, P < 0.001. A table of intercorrelations is presented between mother and father reports of the PDH and all other variables (see Table 2). Correlations indicate strong associations within parent PDH across time, while moderate correlations of PDH across time were found between mothers and fathers. Although two cumulative composites of all risk factors for mothers and fathers were planned, the low correlations among variables suggested that such composites would not have adequate reliability (i.e. indices of maternal well-being and mother–child relationship were uncorrelated).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Mothers |

Fathers |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Range | Alpha | Mean | SD | Range | Alpha | T-test | |

| PDH at 36 months | 47.42 | 14.679 | 69 | 0.905 | 44.64 | 12.310 | 58 | 0.877 | 1.945† |

| PDH at 48 months | 50.21 | 14.458 | 65 | 0.907 | 43.41 | 12.796 | 64 | 0.877 | 3.366** |

| PDH at 60 months | 49.87 | 13.999 | 70 | 0.880 | 45.05 | 13.655 | 55 | 0.908 | 3.462** |

| SCL at 36 months | 24.31 | 18.461 | 92 | 0.839 | 17.15 | 15.876 | 85 | 0.854 | 3.381** |

| DAS at 36 months | 107.26 | 24.162 | 118 | 0.9 | 110.25 | 19.377 | 99 | 0.822 | −1.047 |

| P–C pleasure at 36 months | 1.55 | 0.648 | 3.50 | – | 1.62 | 0.681 | 3.17 | – | −0.432 |

| Education | 14.34 | 2.402 | 10 | – | 13.97 | 2.725 | 14 | – | 1.577 |

PDH, parenting daily hassles; SCL, Symptom Checklist; DAS, Dyadic Adjustment Scale.

Note: P < 0.07,

P < 0.05,

P < 0.001.

Table 2.

Correlation table of parenting daily hassles over time

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mom PDH36 | - | 0.439** | 0.731** | 0.249* | 0.744** | 0.251* | 0.607** | 0.133 | −0.390** | −0.190 | −0.111 | 0.005 |

| 2. Dad PDH36 | - | 0.359** | 0.566** | 0.363** | 0.686** | 0.350** | 0.201 | −0.433** | −0.414** | 0.013 | 0.034 | |

| 3. Mom PDH48 | - | 0.268* | 0.784** | 0.303* | 0.566** | 0.191 | −0.301* | −0.235* | −0.070 | −0.055 | ||

| 4. Dad PDH48 | - | 0.231* | 0.610** | 0.274* | 0.242* | −0.234* | −0.355** | −0.097 | −0.032 | |||

| 5. Mom PDH60 | - | 0.456** | 0.601** | 0.290* | −0.255* | −0.206 | −0.057 | −0.101 | ||||

| 6. Dad PDH60 | - | 0.442** | 0.349* | −0.229† | −0.405** | 0.086 | 0.005 | |||||

| 7. Mom SCL | - | 0.486** | −0.374** | −0.244* | −0.093 | 0.003 | ||||||

| 8. Dad SCL | - | −0.163 | −0.163 | −0.057 | −0.044 | |||||||

| 9. Mom DAS | - | 0.684** | 0.156 | 0.139 | ||||||||

| 10. Dad DAS | - | 0.119 | 0.178 | |||||||||

| 11. Mom P−C pleasure | - | 0.521** | ||||||||||

| 12. Dad P−C pleasure | - |

PDH, parenting daily hassles; SCL, Symptom Checklist; DAS, Dyadic Adjustment Scale.

Note: P < 0.07;

P < 0.05;

P < 0.001.

Growth models of parenting daily hassles

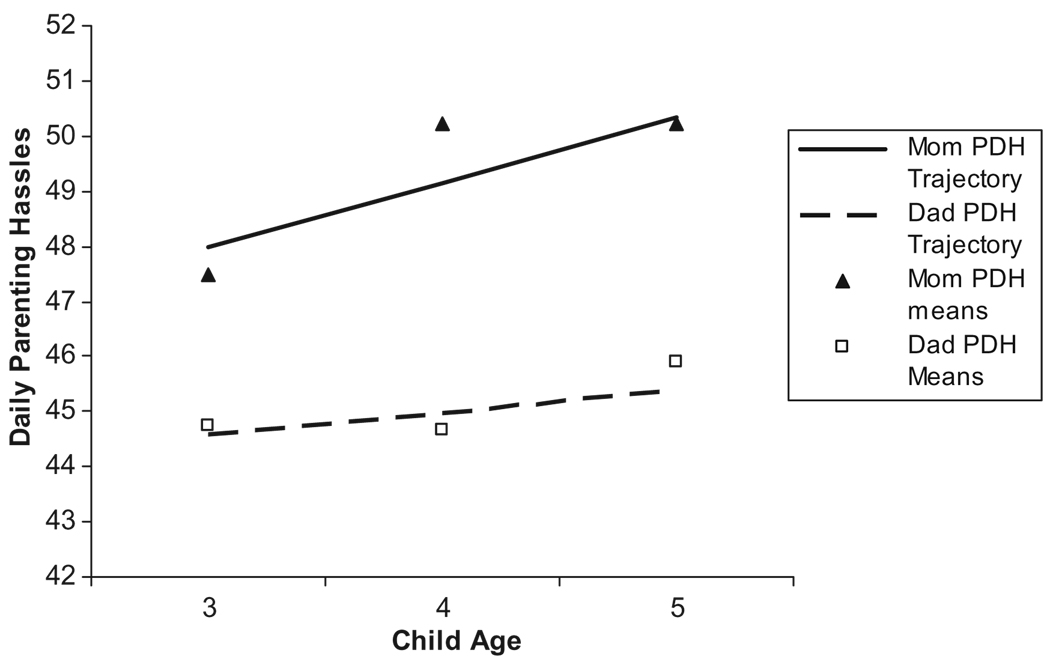

With respect to the general model shown in Fig. 1, the model for mothers’ PDH over time had adequate fit, χ2(1) = 2.750, P = ns, CFI = 0.990, RMSEA = 0.127, SRMR = 0.030. The mean intercept and slope were significantly different from zero. The intercept at 60 months was B = 50.343(SE = 1.395), P < 0.001 and the slope was B = 1.185(SE = 0.527), P = 0.012. Although the intercept had significant variance (s2 = 164.921, P < 0.001), the variance of the slope was nonsigificant (s2 = 4.123, P < ns). Figure 2 represents the latent growth of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting hassles over time, as well as the plotted means.

Figure 2.

Growth models of parenting daily hassles (PDH) over time.

The model for fathers’ PDH initially resulted in an improper solution (negative variance estimate). To solve this problem, the variance of slope was set to zero and the covariance between slope and intercept was set to zero. The resulting model for fathers’ PDH indicated good fit, χ2(3) = 2.003, P = ns, CFI = 1.000, RMSEA = 0.000, SRMR = 0.056. The intercept was significantly different from zero at 60 months, B = 45.155 (SE = 1.407), P < 0.001, and had significant variance (s2 = 14.526, P < 0.001). However, the slope was found to be nonsignficant, B = 0.361 (SE = 0.627), P = ns.

Prediction of parenting daily hassles from well-being

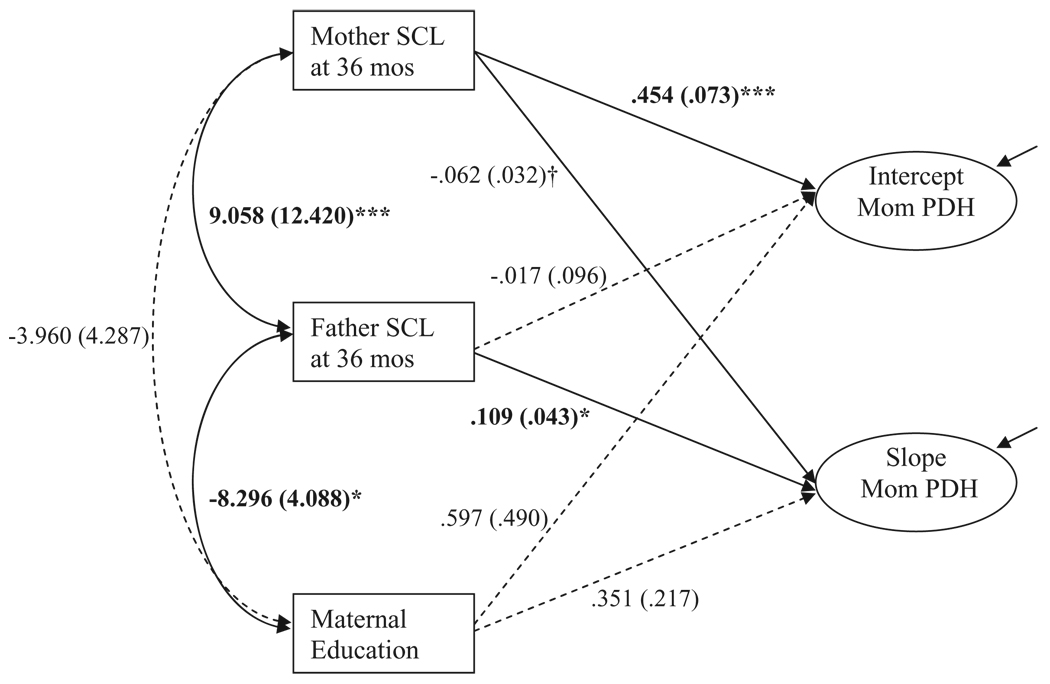

Structural equation modelling was used to test the effects of same parent and cross-parent well-being on the intercept and slope of PDH. Recall that the SCL provides an index of psychological symptomatology where high scores indicate more symptoms. Low scores on this measure are reflective of greater well-being. Same-parent education was also used as a covariate. For models examining fathers’ PDH, parameter estimates were only calculated for the intercept, given the lack of significant slope or slope variance for fathers’ PDH.

For the model of well-being predicting the growth model of mothers’ PDH, the model indicated good fit, χ2(4) = 3.867, P = ns, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00, SRMR = 0.021, and the fit was significantly better than the nested model predicting parenting hassles alone. See Fig. 3 for specific findings. Results indicated that maternal symptomatology at 3 years was associated with a higher intercept of mothers’ PDH at 5 years (B = 0.454, SE = 0.073, P < 0.001), and that fathers’ symptomatology was associated with an increase in the slope of mothers’ parenting hassles over time (B = 0.109, SE = 0.043, P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Parental well-being as predictor of the growth of mothers’ parenting daily hassles (PDH). Numbers represent unstandardized path coefficients, and their associated standard errors. †P < 0.07, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. SCL, parental well-being.

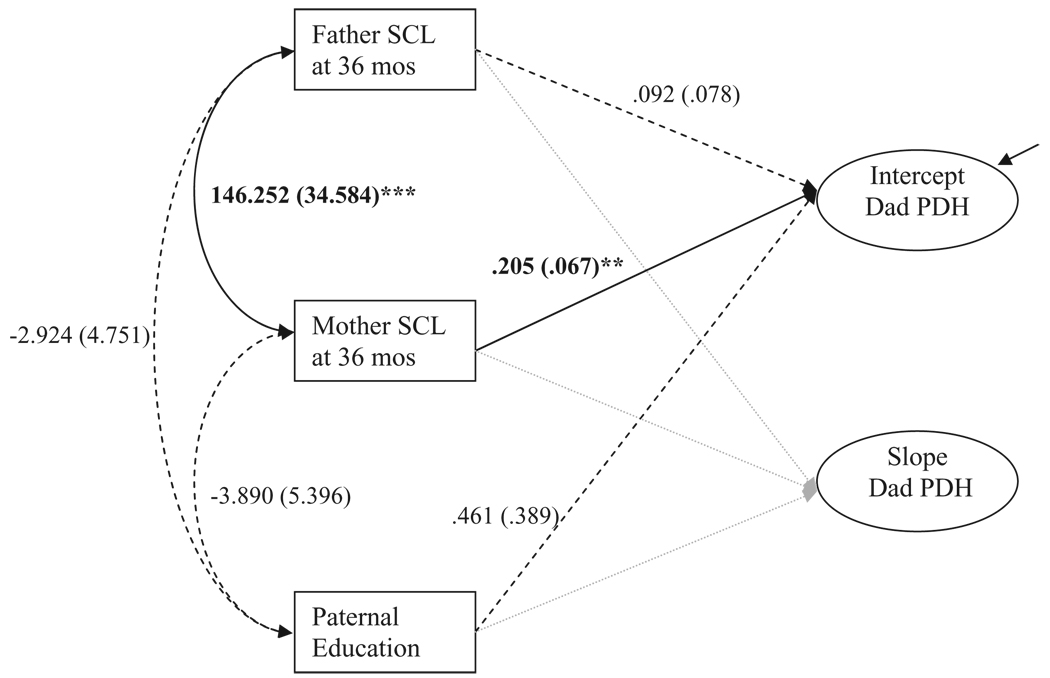

For the model examining fathers’ PDH as predicted by well-being, the model had good fit, χ2(9) = 5.455, P = ns, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00, SRMR = 0.042, and the fit was significantly better than the nested model predicting parenting hassles alone. Results indicated that mothers’ symptomatology at 3 years was positively associated with the intercept for fathers’ daily hassles, B = 0.205 (SE = 0.067), P < 0.001. All other effects of well-being on fathers’ parenting hassles were non-significant. See Fig. 4 for specific findings.

Figure 4.

Parental well-being as predictor of the growth of fathers’ parenting daily hassles (PDH). Numbers represent unstandardized path coefficients, and their associated standard errors. Slope variance was fixed to zero. Grey dashed lines indicate parameters fixed to 0. †P < 0.07, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. SCL, parental well-being.

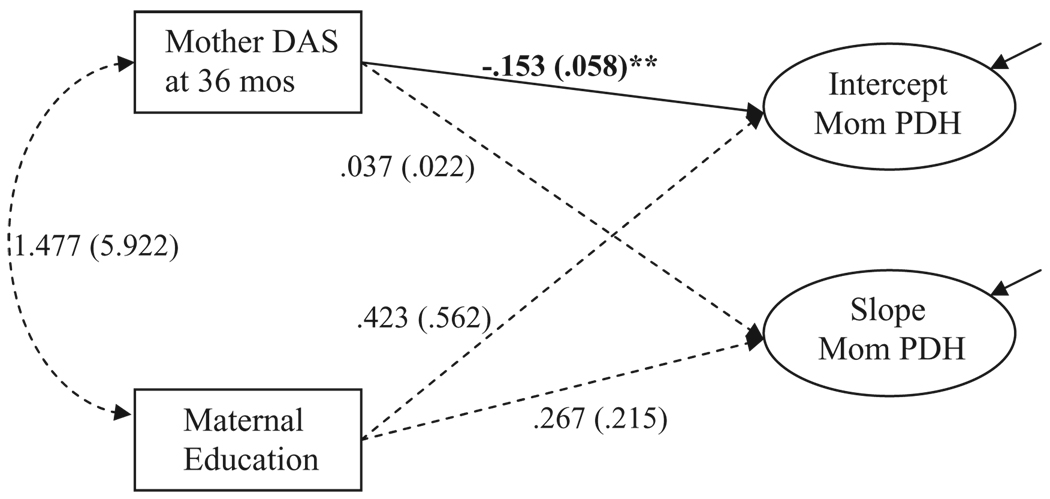

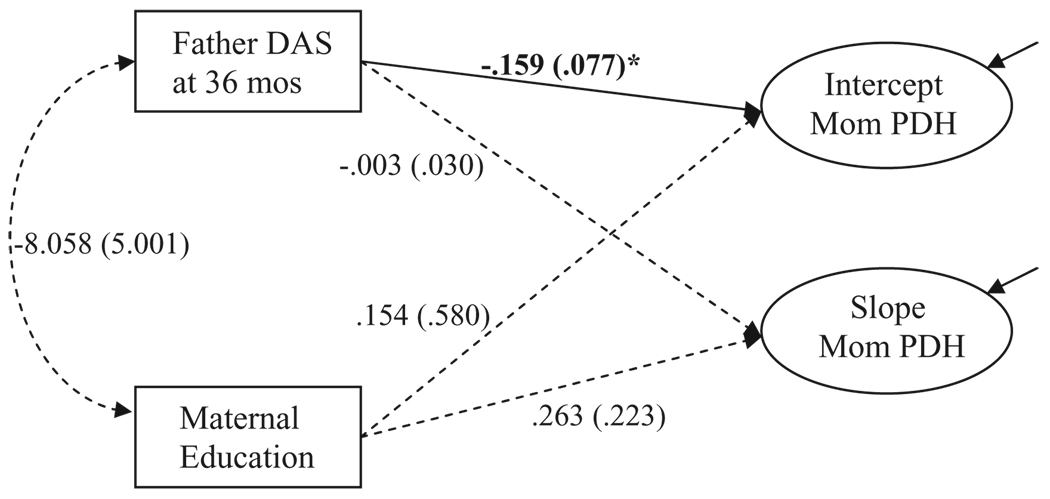

Prediction of parenting daily hassles from marital adjustment

Four models assessing the effect of perceived marital adjustment on parenting hassles were run. For the model with mothers’ PDH as predicted by mother’s reported marital adjustment, the model indicated good fit, χ2(3) = 4.093, P = ns, CFI = 0.994, RMSEA = 0.056, SRMR = 0.027, and the fit was better than the nested model predicting parenting hassles alone. Results indicated that mother-reported marital adjustment at 36 months was negatively associated with the intercept of mothers’ daily hassles, B = −0.153 (SE = 0.058), P < 0.01, but not significantly associated with the slope, B = 0.037 (SE = 0.022), P = ns. See Fig. 5 for specific results. The model assessing mothers’ PDH as predicted by father’s reported marital adjustment found similar results in that adjustment was significantly negatively associated with the intercept (B = −0.159, SE = 0.077, P < 0.05), but not the slope (B = −0.003, SE = 0.030, P = ns) (see Fig. 6 for results). This model also indicated good fit, χ2(3) = 4.453, P = ns, CFI = 0.992, RMSEA = 0.065, SRMR = 0.022, and the fit was better than the nested model predicting parenting hassles alone.

Figure 5.

Mother reported marital adjustment as predictor of the growth of mothers’ parenting daily hassles (PDH). Numbers represent unstandardized path coefficients, and their associated standard errors. †P < 0.07, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. DAS, marital adjustment.

Figure 6.

Father reported marital adjustment as predictor of the growth of mothers’ parenting daily hassles (PDH). Numbers represent unstandardized path coefficients, and their associated standard errors. †P < 0.07, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. DAS, marital adjustment.

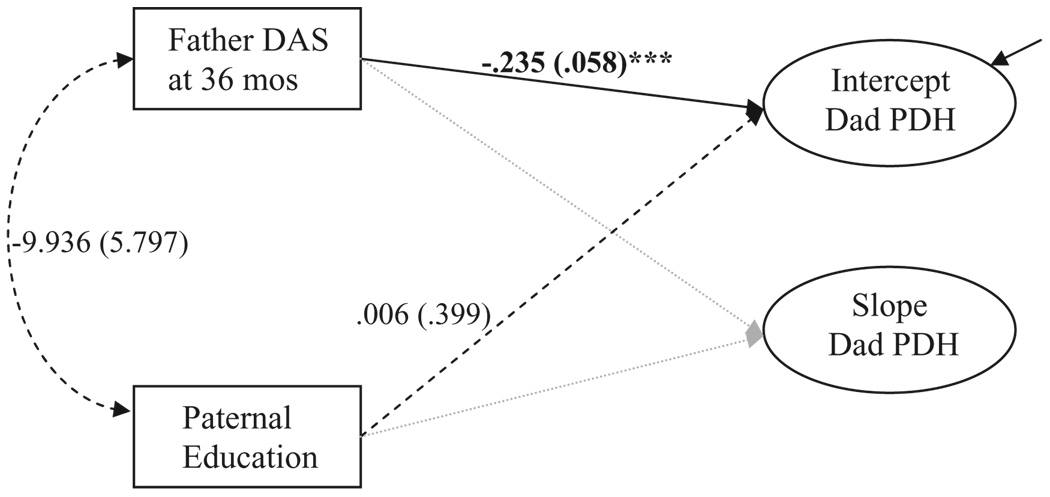

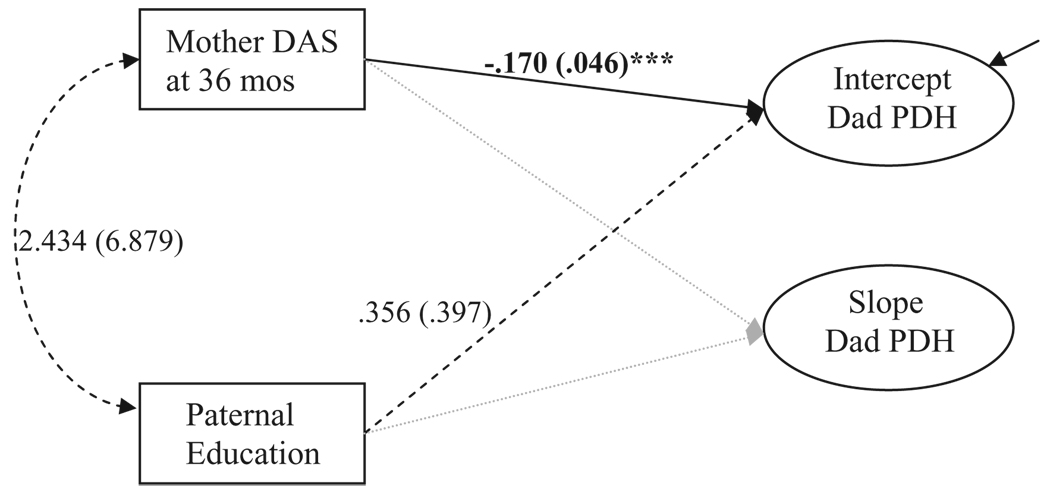

The model examining fathers’ PDH as predicted by father-reported marital adjustment had good fit χ2(7) = 6.192, P = ns, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.000, SRMR = 0.052 (see Fig. 7), and the fit was better than the nested model predicting parenting hassles alone. Results indicated that father-reported marital adjustment at 36 months was associated with a lower intercept of fathering daily hassles, B = −0.235 (SE = 0.058), P < 0.001. The model examining fathers’ PDH as predicted by mother-reported marital adjustment had a similar finding in that marital adjustment was associated with the intercept, B = −0.170 (SE = 0.046), P < 0.001. Specific model findings are presented in Fig. 8. However, this model had less than adequate fit, χ2(7) = 15.472, P < 0.05, CFI = 0.913, RMSEA = 0.108, SRMR = 0.079, although it was better than the nested model predicting parenting hassles alone.

Figure 7.

Father reported marital adjustment as predictor of the growth of fathers’ parenting daily hassles (PDH). Numbers represent unstandardized path coefficients, and their associated standard errors. Slope variance was fixed to zero. Grey dashed lines indicate parameters fixed to 0. †P < 0.07, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. DAS, marital adjustment.

Figure 8.

Mother reported marital adjustment as predictor of the growth of fathers’ parenting daily hassles (PDH). Numbers represent unstandardized path coefficients, and their associated standard errors. Slope variance was fixed to zero. Grey dashed lines indicate parameters fixed to 0. †P < 0.07, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. DAS, marital adjustment.

Prediction of parenting daily hassles from parent–child relationship

As noted previously, the Satorra-Bentler method was used adjust for skew present in the parent–child relationship variables. For the model with mothers’ PDH as predicted by parent–child relationship, the model had good fit, χ2(4) = 6.251, P = ns, CFI = 0.994, RMSEA = 0.049, SRMR = 0.021. There was a significant negative effect of father–child pleasure on the slope for mothering daily hassles, B = −1.919 (SE = 0.876), P < 0.05, such that a positive father–child relationship was associated with a less steep slope for mothering daily hassles (see Fig. 9). The fit for the model assessing the prediction of parent–child relationships onto fathers’ PDH was good, χ2(9) = 10.095, P = ns, CFI = 0.986, RMSEA = 0.027, SRMR = 0.046. However, neither mother–child nor father–child relationship was a significant predictor on either the intercept or slope of fathering daily hassles.

Figure 9.

Parent–child relationship as predictor of the growth of mothers’ parenting daily hassles (PDH). Numbers represent unstandardized path coefficients, and their associated standard errors. †P < 0.07, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Constructs such as resilience and adaptation are often construed as if they are unidimensional in nature and exist as if an individual or family either has it or does not. However, the complexity of families and the individuals within them belie such simple understandings (Luthar et al. 2000), and this would seem to be especially true when developmental risk is part of the nature of a family’s experience. The results of the current study indeed suggest that for families in which a child is early identified as having a developmental delay, parental experience of stress across time is complexly determined by a variety of factors which operate to predict either the level of stress experienced, the trajectory of stress during early the childhood period, or both.

Unique to this study is the inclusion of both mothers’ and fathers’ reports of daily parenting stress across a 2-year period. As noted earlier, stress has been a salient factor of interest in families of children with ID for some time (Crnic et al. 1983; Hauser-Cram et al. 2001; Plant & Sanders 2007), and our results indicate that mothers’ and fathers’ experience of daily parenting stress differs meaningfully not only in the level at which it is experienced but also in degree to which it is experienced over time. Similar to reports of parenting stress in other studies (Deater-Deckard 1998; Baker et al. 2003; Crnic et al. 2005), not only do mothers of children with ID experience higher levels of daily parenting stress than do fathers, but their stress increases meaningfully over the preschool period while fathers’ daily parenting stress does not. That mothers are more stressed and their stress increases over this period may reflect the greater amount of time they spend with the children relative to the father. However, it may also be the case that daily parenting stresses are more salient for mothers because stress may have the greatest effects when it occurs within the domain of life in which one identifies most strongly. Research has suggested that men identify most strongly with their role as breadwinner and worker (Diemer 2002) and fathering has been a somewhat less defined role than mothering (Belsky & Rovine 1990; Erel & Burman 1995). As such, we are only beginning to understand fathering processes within the context of high-risk children (Gray 2003).

Although our results support emerging findings about differences in parenting stress between mothers and fathers, it is apparent that the processes operating to determine the nature of this stressful experience are characterised by complexity. Previous research has provided some guidance in identifying several factors that might explain the range of functioning in stressful experience for parents of children with early ID (e.g. psychological well-being, marital adjustment, positive parent–child relationships); however, our results indicate that factors associated with more resilient functioning in mothers and fathers operate in fairly specific contexts rather than to more general effect. Further, we attempted to explore models of resilience from two perspectives in our study of parents: within-person individual influences and crossover influences. These two perspectives offer a greater sense of the complexity involved in understanding more resilient functioning, as the crossover influences produced generally stronger contributors and father-related processes were particularly important to mother’s reported stress.

Individual mother and father prediction

Despite differences in the level and trajectory of daily parenting stress between mothers and fathers, there was more similarity than difference in the operation of factors that predicted stressful experience. Similarities are apparent predominantly in factors that represent quality dyadic relationships, although the predictions to stressful experience varied. Marital quality was a clear compensatory factor for both mothers and fathers, but neither a positive mother–child relationship nor a positive father–child relationship served to lessen the experience of daily parenting stress for mothers or fathers, respectively. And although mothers’ reported marital quality was associated with the overall level of stress experienced, it was unrelated to the degree to which mothers’ daily parenting stress increased across this period. Only psychological well-being differentiated mothers’ and fathers’ experience of stress; greater maternal well-being was associated with lower reported daily parenting stress for mothers but fathers’ psychological well-being was not associated with his own reported daily parenting stress.

The findings supporting marital quality as a compensatory factor that differentiates the experience of parenting stress for parents of children with ID fit well with the existing literature (Kersh et al. 2006). The failure to find similar effects for a positive parent–child relationship was somewhat surprising as a high-quality parent–child relationship between parents and children with ID has been shown to be protective with respect to multiple child outcomes (Mink et al. 1983; Hauser-Cram et al. 1999; Spiker et al. 2002). Yet, we still know little about the direct association between parent–child relationships and the experience of daily parenting stressors. Perhaps a positive parent–child relationship may help the child develop better skills in communication and social relationships (Guralnick et al. 2008), but this may not completely shield the parent from the challenges of raising a child with developmental disabilities.

Crossover influences

Beyond the individual within-parent influence model, we hypothesised that crossover effects may be operative in families of children with ID in which fathering factors might influence the nature of mothers’ stressful experience and mothering factors might influence fathers’ experience of stress. We found that crossover effects are indeed present in families of young children with ID, and in fact, they tended to be more important to resilient functioning than did the within-parent processes. With respect to parent’s well-being and marital adjustment, both parents’ level of psychological symptoms and more positive marital adjustments influenced the others’ experience of stress. Mothers’ well-being helped fathers experience lower levels of parenting hassles whereas fathers’ well-being was associated with less increasing parenting hassles across time for mothers, replicating findings by Hastings et al. (2005). These connections are well in line with the processes of emotional transmission between husbands and wives that have been articulated by Larson & Almeida (1999), which suggest that events or emotions in one family members’ experience can be related to subsequent emotion or experience in another family member.

Of interest, however, was the finding that a positive father–child relationship early on helped prevent increasing stress in the mothers across the preschool period. The same was not true for the mother–child relationship influencing fathers’ stress. Larson & Almeida (1999) have suggested that within family emotion transmission more typically flows from husband to wife than from wife to husband, and again this may reflect the greater cultural salience of within family processes for women than men. Regardless, Rusbult & Van Lange (1996) have suggested that the capacity for one partner’s psychological states and actions to influence those of the other partner is a defining feature of a close relationship, and the nature of such processes appear to be important in facilitating more resilient functioning for parents of children with ID.

Nature of stress

The degree to which parents experience stress is an important facet of resilient functioning, as high stress has been related to a variety of problematic outcomes for families, parents and children (Crnic & Low 2002). Parents of children with ID have been the focus of much stress research, and the vast majority of this research has indicated that these parents experience higher levels of stress than do families of children who are typically developing (Baker et al. 2003). However, it is unclear that the heightened parenting stress is due solely to the presence of the developmental delay and increased support needs (Hodapp et al. 2003). Findings have indicated that it was the comorbid behaviour problems associated with the ID that was related to parenting stress, rather than the delay itself. Blacher et al. (2005) have also examined the range of factors that may affect stress levels in parents of children with ID, including parental factors, contextual factors, siblings, parenting and cognitions. Identifying those mechanisms by which parent’s stress responses are minimised or decreasing over time remains an important focus of research in families of children with ID, and the findings from the present study suggest that a number of factors operate complexly to keep daily parenting stresses lower for these parents and prevent their increase across time, at least for mothers.

Yet, stress has been measured in a variety of ways across studies of parents of children with ID, and variability in the stress constructs may be important in understanding the nature of parental response and resilience. The current study focused exclusively on parents’ perceptions of the daily hassles of parenting, which involve the potentially demanding and challenging events that parents experience everyday in interaction with their children. PDH have proven to be of major adaptational significance to parents, both in relation to their own well-being and in relation to quality of parenting and children’s development (Crnic & Low 2002; Crnic et al. 2005), but this stress context has not been well explicated in comparison with contexts that address major life stresses (Crnic & Low 2002), more general parenting stresses (Hassall et al. 2005; Plant & Sanders 2007) or stresses that are specific to children with ID (Friedrich et al. 1983.). Research that integrates multiple perspectives on parents’ stress experience will not only further differentiate parental response, but may provide a more complete picture for the study of resilience in families of children with ID.

Limitations

Despite the findings noted above, there are a few limitations that are important to note. First, the parent–child interaction variables were slightly skewed and had little variance. Yet, the findings were slightly skewed such that parent–child dyadic relationships showed less pleasure, rather than more pleasure, as is sometimes reported with observed interactions. This does not indicate that parents and children had negative interactions; it only suggests that the interactions were not exuberantly positive. This may be because these families were observed in naturalistic contexts when they may have also been engaged with other children and completing other tasks around the home. Second, the study did have an attrition rate of 20% across the 2 years. These rates of attrition are in keeping with other longitudinal studies of children with ID (Hastings et al. 2006), and there were no differences in attrition as a function of any study variable. Nonetheless, missing data techniques were used in order to account for subject loss in the data.

It should also be noted that our measure of parental well-being actually indexed the quantity of psychological symptomatology reported by the parents. Although it would be preferable to assess well-being from the perspective of the positive range of functioning, the absence of psychological symptoms is one important marker of resilient functioning when a population has putative risk for psychopathology. Lastly, the study examined mothers and fathers separately across different possible compensatory factors. This was intentional to carefully examine crossover effects separately while minimising multicolinearity. However, in the future, it would be interesting to examine mothers and fathers stress in the same model to explore the moderating effects of parent gender more specifically.

Summary

There is substantial evidence that the stresses in families of children with ID are meaningful, and this appears to be the case regardless of the nature of that stress. Despite the consistency with which stress emerges as an important factor, it is also apparent that many families of children with ID function well across important domains (Blacher & Baker 2007) which implies the presence of resilience processes. Resilience is a multifaceted construct, and it is necessary that it be understood from multiple perspectives (Luthar et al. 2000). As our understanding of families and children at risk expands to embrace greater complexity in the models that explain resilience and the range of parental functioning over time, it is critical that a more systemic approach be included. Both fathers and mothers need to be included in our research models, as it is apparent that stress processes are not shared entirely across the preschool period in parents of children with ID. Likewise, the factors leading to resilient fathers and mothers are not fully similar. Although individual parent characteristics and high-quality dyadic relationships contribute to emerging resilience in parents of children with ID, parents also affect each others’ adaptations in ways that have not been previously considered in these families.

Acknowledgements

Data collection for this study was funded through the Collaborative Family Study, supported with a grant from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development, #34879-1459 (Keith Crnic, Principal Investigator; Bruce Baker, Jan Blacher, and Craig Edelbrock, co-Principal Investigators).The first author was also supported by Institutional Training Grant T32MH018387 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

References

- Baker BL, Blacher J, Kopp CB, Kraemer B. Parenting children with mental retardation. International Review of Research in Mental Retardation. 1997;20:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, Blacher J, Crnic K, Edelbrock C. Behavior problems and parenting stress in families of three year old children with and without developmental delays. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2002;107:433–444. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2002)107<0433:BPAPSI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, McIntyre LL, Blacher J, Crnic K, Edel-brock C, Low C. Pre-school children with and without developmental delay: behaviour problems and parenting stress over time. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2003;47:217–230. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, Blacher J, Olson MB. Preschool children with and without developmental delay: behaviour problems, parents’ optimism, and well-being. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005;49:575–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Rovine M. Patterns of marital change across the transition to parenthood: pregnancy to three years postpartum. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Crnic K, Gable S. The determinants of coparenting in families with toddler boys: spousal differences and daily hassles. Child Development. 1995;66:629–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacher J, Baker BL. Positive impact of intellectual disability on families. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2007;112:330–348. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[0330:PIOIDO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacher J, Hatton C. Families in context: influences on coping and adaptation. In: Odom SL, Home RH, Snell ME, Blacher J, editors. Handbook of Developmental Disabilities. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 531–546. [Google Scholar]

- Blacher J, Baker BL, Braddock DL. Family response to disability: the evolution of family adjustment and coping. In: Blacher J, Baker BL, Braddock DL, editors. Families and Mental Retardation: A Collection of Notable AAMR Journal Articles Across the 20th Century. Washington, D.C.: American Association on Mental Retardation; 2002. pp. 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Blacher J, Neece CL, Paczkowski E. Families and intellectual disability. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2005;18:507–513. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000179488.92885.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal M, Nelson L, Poe M. Growth curve analysis: an introduction to various methods for analyzing longitudinal data. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2006;71:65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Fine MA. Modeling parenting stress trajectories among low-income young mothers across the child’s second and third years: factors accounting for stability and change. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:584–594. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicirelli VG. An examination of the trajectory of the adult child’s caregiving for an elderly parent. Family Relations. 2000;49:169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Jr, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development. 1992;63:526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creasey G, Reese M. Mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of parenting hassles: associations with psychological symptoms, non-parenting hassles, and child behavior problems. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1996;17:393–406. [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Greenberg MT. Minor parenting stresses in young children. Child Development. 1990;61:1628–1637. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Booth CL. Mothers’ and father’s perceptions of daily hassles of parenting across early childhood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1991;53:1042–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Low C. Everyday stresses and parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting, 2nd Edition, Vollume 5: Practical Issues in Parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum; 2002. pp. 243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Friedrich WN, Greenberg MT. Adaptation of families with mentally retarded children: a model of stress, coping, and family ecology. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1983;88:125–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Hoffman C, Gaze C. Cumulative parenting stress across the preschool period: relations to maternal parenting and child behaviour at age 5. Infant and Child Development. 2005;14:117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Bumpus ME, Maguire MC, McHale SM. Linking parents’ work pressure and adolescents’ well-being: insights into dynamics in dual-earner families. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1453–1461. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.6.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Interparental discord, family process, and developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental Psychopathology:Vol 3: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2006. pp. 86–128. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K. Parneting stress and child adjustment: some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1998;5:314–332. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K. Parenting stress and children’s development: introduction to the special issue. Infant and Child Development. 2005;13:111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. BSI Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA. Constructions of provider role identity among African American men: an exploratory study. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2002;8:30–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donenberg F, Baker BL. The impact of young children with externalizing behaviors on their families. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:179–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00911315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Stycker LA, Fuzhong L, Alpert A. An Introduction to Latent Variable Growth Curve Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. Manwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhower AS, Baker BL, Blacher J. Preschool children with intellectual disability: syndrome specificity, behaviour problems, and maternal well-being. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005;49:657–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson E, Robertson J, Wood J. Levels of psychological distress experienced by family careers of children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities in an urban conurbation. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2004;17:77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Stuctural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2001;8:430–457. [Google Scholar]

- Erel O, Burman B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman M, McDonald L, Serbin L, Stack D, Secco ML, Yu CT. Predictors of depressive symptoms in primary caregivers of young children with or at risk for developmental delay. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2007;51:606–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler DJ, Hodapp RM, Dykens EM. Stress in families of young children with Down syndrome, Williams syndrome, and Smith-Magenis syndrome. Early Education and Development. 2000;11:395–406. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich WN, Greenberg MT, Crnic KA. A short form of the questionnaire on resources and stress. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1983;88:41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DE. Gender and coping: the parents of children with high functioning autism. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56:631–642. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn P, Berry P. Some financial costs of caring for children with Down Syndrome at home. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability. 1987;13:187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Guralnick MJ, Neville B, Hammond MA, Connor RT. Linkages between delayed children’s social interactions with mothers and peers. Child Development. 2007;78:459–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnick MJ, Neville B, Hammond MA, Conner RT. Mothers’ social communicative adjustments to young children with mild developmental delays. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2008;113:1–18. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2008)113[1:MSCATY]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassall R, Rose J, McDonald J. Parenting stress in mothers of children with an intellectual disability: the effects of parental cognitions in relation to child characteristics and family support. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005;49:405–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP. Child behaviour problems and partner mental health as correlates of stress in mothers and fathers of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2003;47:231–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP, Kovshoff H, Ward NJ, Espinosa FD, Brown T, Remington B. Systems analysis of stress and positive perceptions in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005;35:635–644. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP, Daley D, Burns C, Beck A. Maternal distress and expressed emotion: cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships with behavior problems of children with intellectual disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2006;111:48–61. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111[48:MDAEEC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser-Cram P, Warfield ME, Shonkoff JP, Krauss MW, Upshur CC, Sayer A. Family influences on adaptive development in young children with Down Syndrome. Child Development. 1999;70:979–989. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser-Cram P, Warfield ME, Shonkoff JP, Krauss MW. The development of children with disabilities and the adaptation of their parents: theoretical perspective and empirical evidence. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2001;66:6–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman T. Parents of children with disabilities: resilience, coping, and future expectations. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2002;14:159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Herring S, Gray K, Taffe J, Tonge B, Sweeney D, Einfeld S. Behaviour and emotional problems in toddlers with pervasive developmental disorders and developmental delay: associations with parental mental health and family functioning. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006;50:874–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodapp RM, Ricci LA, Fidler DJ. The effects of the child with Down Syndrome on maternal stress. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2003;21:137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L. Parents’ feelings about retarded children. In: Blacher J, Baker BL, Braddock DL, editors. Families and Mental Retardation: A Collection of Notable AAMR Journal Articles Across the 20th Century. Washington, D.C.: American Association on Mental Retardation; 1953. pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kersh J, Hedvat TT, Hauser-Cram P, Warfield ME. The contribution of marital quality to the well-being of parents of children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006;50:883–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Almeida DM. Emotional transmission in the daily lives of families: a new paradigm for studying family process. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, DeLongis A, Folkman S, Gruen R. Stress and adaptational outcomes: the problem of confounded measures. American Psychologist. 1985;40:770–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S. Resilience and Vulnerability: Adaptation in the Context of Childhood Adversities. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S. Resilience in development: a synthesis of research across 5 decades. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental Psychopathology Vol. 3: Risk, Disorder and Adaptation. 2nd edn. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2007. pp. 739–795. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S, Zelazo LB. Research on resilience: an integrative review. In: Luthar S, editor. Resilience and Vulnerability: Adaptation in the Context of Childhood Adversitie. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 510–550. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald DA, Almeida DM. The interweave of fathers’ daily work experiences and fathering behaviors. Fathering: Special Issue:Work/Family Issues for Fathers. 2004;2:235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Marfo K. Maternal directiveness in interactions with mentally handicapped children: an analytical commentary. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1990;31:531–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb00796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mink IT, Nihira K, Meyers CE. Taxonomy of family life styles: I. Homes with TMR children. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1983;87:484–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulsow M, Caldera YM, Pursley M, Reifman A, Huston AC. Multilevel factors influencing maternal stress during the first three years. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:944–956. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 4th edn. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson MB, Hwang CP. Depression in mothers and fathers of children with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2001;45:535–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2001.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr RR, Cameron SJ, Dobson LA, Day DM. Age-related changes in stress experienced by families with a child who has developmental delays. Mental Retardation. 1993;31:171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish SL, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Floyd F. Economic implications of caregiving at midlife: comparing parents with and without children who have developmental disabilities. Mental Retardation. 2004;42:413–426. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2004)42<413:EIOCAM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry A. A model of stress in families of children with developmental disabilities: clinical and research applications. Journal on Developmental Disabilities. 2005;11:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Perry-Jenkins M, Repetti RL, Crouter AC. Work and family in the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:981–998. [Google Scholar]

- Plant KM, Sanders MR. Predictors of caregiver stress in families of preschool-aged children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2007;51:109–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottie CG, Ingram KM. Daily stress, coping, and well-being in parents of children with Autism: a multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:855–864. doi: 10.1037/a0013604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risdal D, Singer GHS. Marital adjustment in parents of children with disabilities: a historical review and meta-analysis. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2004;29:95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Roach MA, Barratt MS, Miller MJ, Leavitt LA. The structure of mother-child play: young children with Down syndrome and typically developing children. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:77–87. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Van Lange PAM. Interdependence processes. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW, editors. Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 564–596. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Johnston JH, Siegel JM. Assessing the impact of life changes: development of the life experiences survey. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1978;46:932–946. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.5.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In: von Eye A, Clogg CC, editors. Latent Variables Analysis: Applications for Developmental Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 399–419. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. The measurement of marital quality. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 1979;5:288–300. doi: 10.1080/00926237908403734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiker D, Boyce GC, Boyce LK. Parent-Child interactions when young children have disabilities. International Review of Research in Mental Retardation. 2002;25:35–70. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart W, Barling J. Fathers’ work experiences effect children’s behaviors via job-related affect and parenting behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1996;17:21–232. [Google Scholar]

- Williford AP, Calkins SD, Keane SP. Predicting change in parenting stress across early childhood: child and maternal factors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:251–263. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfensberger W, Menolascino F. A theoretical framework for management of parents of the mentally retarded. In: Menolascino F, editor. Psychiatric Approaches to Mental Retardation. New York: Basic Books; 1970. pp. 475–493. [Google Scholar]

- Wortman C, Biernat M, Lang E. Coping with role overload. In: Frankenhauser M, et al., editors. Women, Work, and Health: Stress and Opportunities. New York: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]