Abstract

Mitochondrial genome alterations have been suggested to play an important role in carcinogenesis. The D-loop region of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) contains essential transcription and replication elements, and mutations in this region may serve as a potential sensor for cellular DNA damage and a marker for cancer development. Using data and samples from the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study, we investigated MnlI restriction sites located between nucleotides 16,106 and 16,437 of the mtDNA D-loop region to evaluate restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) patterns in tumor tissue from 501 primary breast cancer patients and as compared to tumor tissue from 203 women with benign breast disease (BBD). RFLP patterns in correspondingly-paired, adjacent, non-tumor tissues taken from 120 primary breast cancer patients and 59 BBD controls were also evaluated. Five common RFLP patterns were observed, and no significant differences were observed in the distribution of these patterns between tumor and adjacent non-tumor tissue samples from breast cancer patients and tissue samples from BBD controls. On the other hand, somatic MnlI site mutations, defined as a difference in MnlI RFLP pattern between tumor tissue and the corresponding, adjacent, non-tumor tissue, occurred more frequently in breast cancer tumor tissue (28.3%) than in BBD tumor tissue (15.3%) (p=0.05) and more frequently in proliferative BBD (13.0%) than non-proliferative BBD (7.1%). Our data suggest that somatic MnlI site mutations may play a role in the pathogenesis of breast cancer.

Keywords: Mitochondrial DNA, MnlI restriction site mutation, breast cancer risk

INTRODUCTION

Mitochondria play a critical role in energy production and oxidative phosphorylation [1]. Defects in mitochondrial function are suspected to contribute to the development and progression of cancer [2–4]. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is particularly susceptible to damage by environmental carcinogens because it contains no introns, has no protective histones or non-histone proteins, and is exposed continuously to endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) [4;5]. Therefore, mtDNA may serve as a potential sensor for cellular DNA damages and a marker for cancer development. The displacement loop (D-loop) is the major control site for mtDNA replication and transcription [4]. Genetic variability in the D-loop region has been suggested to affect the function of the respiration chain that is responsible for high ROS levels and could contribute to cancer initiation [5;6].

Several mtDNA mutations in the mtDNA D-loop have been reported in the breast cancer tissues [3;7–9], including the MnlI restriction sites located between nucleotide positions (np) 16,106 and 16,437 [3]. However, no study has been conducted to evaluate the association of mtDNA D-loop MnlI site mutations with breast cancer risk. Furthermore, MnlI site mutation in benign breast diseases (BBD) has not been investigated.

mtDNA mutation itself may have a functional effect, which may alter free radical production and apoptosis. A mutant mitochondrial genome may have a replication advantage in a particular mitochondria, and such mitochondria may selectively proliferate over the other mitochondria in the same cell [10]. Therefore, a single cell bearing a mutant mitochondrial genome may acquire a selective growth advantage during tumor evolution, allowing it to become the predominant cell type in the tumor cell population. We hypothesized that mtDNA D-loop MnlI site mutation might play a role in the development of breast cancer. We tested this hypothesis in a population-based case-control study conducted in Shanghai, China.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects

Included in this study was a subset of patients who were recruited as parts of the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study, a population-based case-control study conducted among women in Shanghai [11]. These patients were diagnosed with breast cancer or BBD between 1996 and 1998 and were identified through a network of major hospitals that treat approximately 70% of breast cancer patients in urban Shanghai. Including in the current study were 501 breast cancer patients and 203 women with BBD whose tumor tissues were collected. Adjacent non-tumor tissues were also collected from 120 breast cancer patients and 59 BBD patients. These samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen as soon as possible, typically within 10 minutes after resection. Samples were stored at −80°C until the relevant assays were performed. Medical charts were reviewed using a standard protocol to obtain information on cancer treatment, clinical stage, and cancer characteristics, such as estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) status. Two senior pathologists reviewed the pathology slides to confirm the diagnosis of breast cancer and BBD. BBDs were classified based on published criteria developed by Page and colleagues [12].

Detailed information on demographic factors, menstrual and reproductive history, hormone use, dietary habits, previous disease history, physical activity, tobacco and alcohol use, weight history, and family history of cancer was collected during an in-person interview by trained study interviewers using a structured questionnaire. Anthropometrics were taken according a standard protocol [13]. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of all institutes involved in the study.

Laboratory Methods

Total DNA was extracted from breast tissue using TRIzol® Reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The concentration of DNA was measured with a TBS-380 Fluorometer (Turner Biosystems, Sunnyvale, CA) using the DNA-specific binding dye Hoechst 33258 (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Mutations in MnlI restriction sites [CCTC(N)7] were determined with a PCR-RFLP method reported previously by Richard et al [3] with modifications. Briefly, the primers were: 16106F: 5’-TGCCAGCCACCATGAATATT-3’ and 16437R: 5’-TCTTGTGCGGGATATTGATTT-3’. The PCR reactions were performed in a 30 µL mixture containing 5 ng template DNA, 1 unit Hotstar Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), 1x Qiagen PCR buffer, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.2 mmol/L each of deoxynucleotide triphosphates, and 0.5 µmol/L each primer. After denaturation at 95°C for 15 minutes, the PCR was performed in 38 cycles of 94°C for 45 seconds, 62°C for 45 seconds, and 72°C for 45 seconds. The PCR was completed by a final extension cycle at 72°C for 10 minutes.

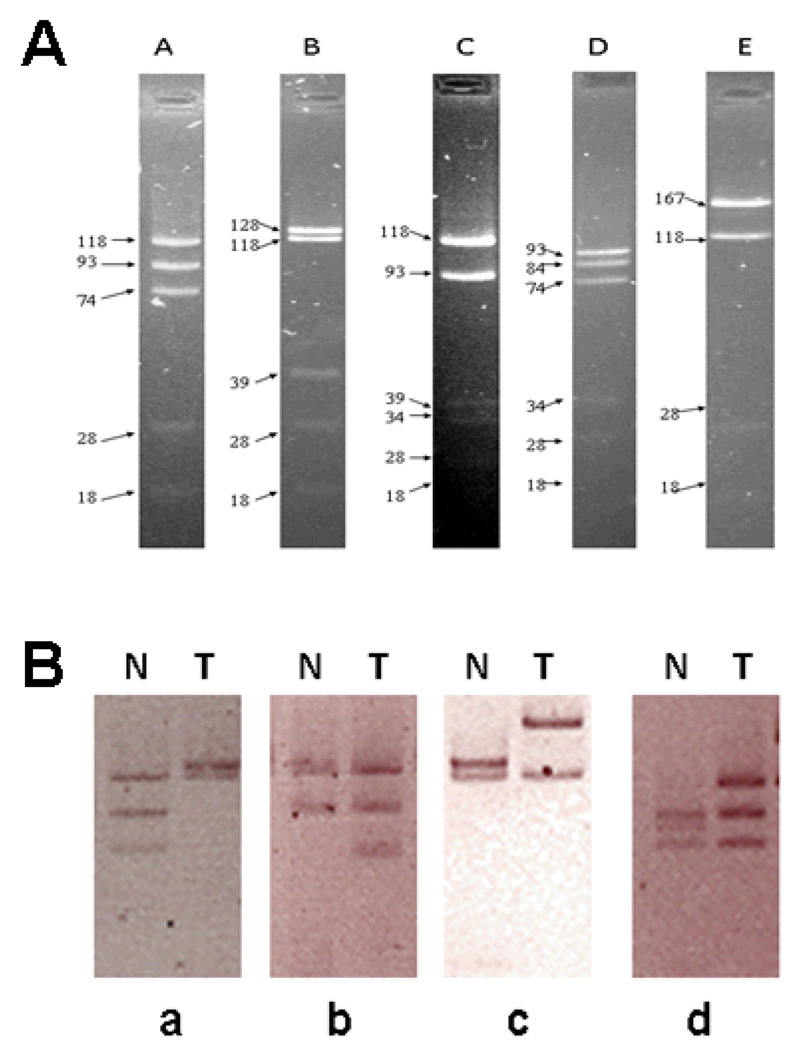

This reaction yields a 332 bp product, spanning from np16106 to 16437 within the human mtDNA D-loop region. Ten microliters of PCR product were digested with 5 units of the MnlI restriction enzyme (NEB, Beverly, MA) following the manufacturer’s instructions in a final reaction volume of 30 µL. The restriction fragments were separated by gel electrophoresis in 1X sodium borate buffer (Faster Better Media, Hunt Valley, MD) on 4.0% NuSieve GTG agarose gels containing ethidium bromide; the gel was photographed on a UV transilluminator. The gel patterns for each sample were scored according to MnlI fragment sizes (Table 1 and Fig 1A). Samples apparently not conforming to any single pattern (scored as “atypical”), or displaying multiple phenotypes, were re-run through the entire PCR-RFLP process and re-evaluated to assure complete enzymatic digestion and PCR fidelity. Somatic MnlI site mutation was defined as deference in MnlI RFLP alteration between tumor tissue and corresponding non-tumor tissue.

Table 1.

MtDNA D-loop MnlI site RFLP pattern and associated gel fragment sizes

| MnlI site RFLP pattern | RFLP fragment sizes |

|---|---|

| A | 118, 93, 74, 28, 18 |

| B | 128, 118, 39, 28, 18 |

| C | 118, 93, 39, 34, 28, 18 |

| D | 93, 84, 74, 34, 28, 18 |

| E | 167, 118, 28, 18 |

Figure 1. Representative mtDNA D-loop MnlI site RFLP patterns.

Panel A: Representative gel electrophoresis of DNA fragments for 5 major RFLP patterns.Panel B: Representative examples of RFLP patterns of breast tumor tissue (T) and adjacent non-tumor tissue (N) from 4 subjects analyzed by gel electrophoresis. (a) N: pattern A (118, 93, and 74 bps, from top to bottom); T: pattern B (128 and 118 bps). (b) N: pattern C (118 and 93 bps); T: pattern A (118, 93, and 74 bps). (c) N: pattern B (128 and 118 bps); T: pattern E (167 and 118 bps). (d) N: pattern D (93, 84, and 74 bps); T: pattern A (118, 93, and 74 bps). Small DNA fragments (39, 34, 28, and 18) are not shown.

The laboratory staff was blind to the identity of study subjects. QC samples were included in all genotyping assays. Each 96-well plate contained one water, two Centre d’Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH) 1347-02 DNA samples, two blinded QC DNA samples, and two unblinded QC DNA samples. Blinded and unblinded QC samples were taken from the second tube of study samples included in the study. The MnlI site RFLP patterns determined for the QC samples were in complete agreement with those determined for the study samples.

Statistic Analysis

Breast cancer patients were compared to BBD patients (control) in data analysis. Chi-square statistics were used to evaluate case-control differences in the distribution of the MnlI sites. Logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) for the association of the MnlI sites with breast cancer risk. Potential confounders including menopausal status, body mass index (BMI), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) were adjusted for in logistic regression models. Analyses stratified by TNM stages, menopausal status, age, BMI, WHR, and years of menstruation were also conducted to evaluate the homogeneity of the association. P values < 0.05 (2-sided probability) were interpreted as being statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS software (Version 9.0; SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Table 2 compared the selected demographic characteristics and selected major breast cancer risk factors between breast cancer patients and BBD patients. Compared to BBD patients, breast cancer patients had, in general, older age at the time of interview, lower education levels, were more likely to be post-menopausal, and less likely to have a history of fibroadenoma.

Table 2.

Comparison of cases of breast cancer and benign breast diseases by selected demographic characteristics and major risk factors, the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study

| Subject Characteristic | Breast Cancer (n=501) |

BBD (n=203) |

P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic factors | |||

| Age (years, x̄ ± sd ) | 47.8 ± 7.7 | 43.5 ± 7.2 | <0.001 |

| Education: < middle school (%) | 13.0 | 4.9 | |

| = middle school (%) | 45.5 | 40.9 | |

| > middle school (%) | 41.5 | 54.2 | 0.001 |

| Major risk factors | |||

| Breast cancer in first-degree relatives (%) | 4.0 | 2.5 | 0.322 |

| Ever had breast fibroadenoma (%) | 7.8 | 21.2 | <0.001 |

| Post-menopausal (%) | 32.9 | 10.8 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (x̄ ± sd ) | 23.7 ± 3.2 | 23.2 ± 3.7 | 0.109 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio (x̄ ± sd ) | 0.80 ± 0.06 | 0.80 ± 0.06 | 0.071 |

From χ2 test (categorical variables) or T test (continuous variables).

We observed 5 common RFLP patterns of MnlI sites in this study (Fig 1). As shown in Table 3, patterns A and B were the two most common patterns. The MnlI sites RFLP patterns in tumor tissue or adjacent non-tumor tissue, however, did not differ significantly between breast cancer and BBD patients. Similarly, no significant differences were found when analyses were stratified by TNM stages, menopausal status, age, BMI, WHR, and years of menstruation. Among BBD patients, we found no significant differences in MnlI site RFLP patterns between patients who had proliferative tumors and those who had non-proliferative tumors (data not shown).

Table 3.

Association of mtDNA D-loop MnlI site mutation with breast cancer risk

| RFLP pattern | Tumor Tissue, N (%) | Adjacent Non-tumor Tissue, N (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | BBD | OR (95% CI) | Breast Cancer | BBD | OR (95% CI) | |

| A | 201 (40.4) | 75 (37.7) | 1.00 (reference) | 48 (38.7) | 23 (36.5) | 1.00 (reference) |

| B | 102 (20.5) | 39 (19.6) | 0.91 (0.57–1.46) | 30 (24.2) | 10 (15.9) | 1.57 (0.63–3.89) |

| C | 61 (12.3) | 29 (14.6) | 0.71 (0.42–1.23) | 16 (12.9) | 7 (11.1) | 1.25 (0.42–3.72) |

| D | 43 (8.7) | 14 (7.0) | 1.07 (0.54–2.10) | 9 (7.3) | 6 (9.5) | 0.75 (0.23–2.51) |

| E | 35 (7.0) | 19 (9.6) | 0.73 (0.38–1.40) | 4 (3.2) | 8 (12.7) | 0.26 (0.07–1.02) |

| Atypical | 44 (8.9) | 12 (6.0) | 1.40 (0.67–2.92) | 14 (11.3) | 5 (7.9) | 1.68 (0.50–5.61) |

| Other | 11 (2.2) | 11 (2.5) | 0.37 (0.15–0.92) | 3 (2.4) | 4 (6.4) | 0.42 (0.09–2.08) |

| A | 201 (40.4) | 75 (37.7) | 1.00 (reference) | 48 (38.7) | 23 (36.5) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Any other RFLP patterns |

296 (59.6) | 124 (62.3) | 0.85 (0.60–1.21) | 76 (61.3) | 40 (63.5) | 1.01 (0.52–1.96) |

To further investigate whether somatic mutations in the MnlI sites were associated with breast cancer development, we compared change of MnlI RFLP pattern between tumor tissue and the corresponding adjacent non-tumor tissue between breast cancer and BBD patients. Somatic MnlI site mutation (RFLP pattern changes) was more frequently seen in breast cancer tumor tissue (28.3%) than in BBD tumor tissue (15.3%) (OR=2.23; 95% CI: 0.95–5.22) (Table 4). The difference was marginally significant (P=0.05). Age was not associated with somatic MnlI site mutation in either breast cancer patients (p=0.465) or BBD patients (p=0.865). Among breast cancer patients, somatic MnlI site mutation occurred more frequently among patients with an early stage cancer (TNM = 0 & I) than those with a late stage cancer (TNM > 1) (32.2% vs. 16.7%) (OR=2.40; 95% CI: 0.82–6.97). The somatic MnlI site mutation was observed in 3 out of 23 (13.0%) proliferative BBD cases and 2 out of 28 (7.1%) non-proliferative BBD cases (Table 4). The sample size, however, was too small for a meaningful comparison among the BBD group.

Table 4.

Comparisons of mtDNA D-loop MnlI RFLP pattern changes between breast cancer patients and BBD patients, between different TNM stages among breast cancer patients, and between different types of BBD patients

| N | RFLP pattern changea, N (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer vs BBD | |||

| BBD | 59 | 9 (15.3%) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Breast Cancer | 120 | 34 (28.3%) | 2.23 (0.95–5.22) |

| In breast cancer patients | |||

| TNM > I | 30 | 5 (16.7%) | 1.00 (reference) |

| TNM = 0 & I | 90 | 29 (32.2%) | 2.40 (0.82–6.97) |

| In BBD patients | |||

| Proliferative | 23 | 3 (13.0%) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Non-proliferative | 28 | 2 (7.1%) | 0.48 (0.07–3.37) |

The difference of MnlI RFLP patterns between tumor tissues and the corresponding adjacent non-tumor tissues.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first large epidemiologic study that has systematically evaluated mtDNA D-loop MnlI site somatic mutations in tumor tissue and adjacent non-tumor tissue from patients with breast cancer and BBD. Five common RFLP patterns of mtDNA D-loop MnlI sites were observed in our study population. No apparent differences were observed in the distribution of the RFLP patterns between samples from breast cancer patients and BBD patients in either tumor or adjacent non-tumor tissues. However, we found that somatic MnlI site mutation, defined as a difference in MnlI RFLP pattern between tumor tissue and the corresponding adjacent non-tumor tissue, occurred more frequently in breast cancer tumor tissue (28.3%) than in BBD tumor tissue (15.3%). Our observations suggest that MnlI site mutation in the mtDNA D-loop region may contribute to the development of breast cancer. In a previous study conducted in 40 breast cancer cases, mtDNA D-loop MnlI site mutations were observed in 19/40 (47.5%) cases [3].

The mtDNA D-loop is a non-coding sequence of the mitochondrial genome that is implicated in mtDNA replication and transcription. The MnlI restriction sites are not only within this sequence region, but also very close to a novel origin of replication reported recently [14]. Replication of mtDNA could play a central role in the maintenance of mtDNA copy number, and the mitochondrial single-stranded DNA-binding protein (mtSSB), the key nuclear-encoded component of the mtDNA replication apparatus, binds to this region [15]. Therefore, MnlI site mutations may alter mtSSB binding affinities. Since mtSSB is involved in stabilizing D-loops and in the maintenance of mtDNA, it is plausible that impaired binding of mtSSB to MnlI sites may result in decreased mtDNA content. Recently, Yu et al. [16] reported that breast cancer tumors harboring mtDNA D-loop mutations had a significantly lower mtDNA content than tumors without D-loop mutations. In addition, it was recently suggested that human cells exhibit two modes of mtDNA replication: maintenance and induced modes. The induced mode regulates mtDNA at the origin of replication and at the premature termination site at the 3’ end of the D-loop, which plays a major role in the initial recovery following mtDNA depletion [17;18]. Therefore, the different mtSSB binding affinities at the MnlI site may directly or indirectly influence premature termination rate, which in turn altering the recovery rate following mtDNA damage.

The current study has several strengths. We were able to include both tumor tissue and adjacent non-tumor tissue samples from patients diagnosed with breast cancer or BBD, which enabled a direct evaluation of the MnlI site mutation. Our study has large sample size, 501 breast cancer and 203 BBD patents comparing to the only published studies with 40 breast cancer patients. However, our study still lacks adequate power to draw definite conclusion, particularly regarding our finding on difference between proliferative and non-proliferative BBD. In addition, the use of BBD patients as controls is less than optimal, although it is extremely difficult to obtain breast tissue from women without any breast disease. Previous studies have indicated that women with BBD are at an elevated risk of breast cancer as compared with women without BBD [19;20], and BBD and breast cancer may share similar risk factors[21]. Further studies including breast tissues from individuals without disease are warranted to confirm our findings.

In summary, our study suggests that somatic MnlI site mutations may play a role in the etiology of breast cancer. Further studies are warranted to confirm these findings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ms. Qing Wang for her excellent technical laboratory assistance and Ms. Bethanie Hull for technical assistance in manuscript preparation. This study would not have been possible without the support of all of the study participants and research staff of the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study.

Financial Support: This research was supported by United States Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program grant DAMD17-02-1-0603 and National Cancer Institute grants R01 CA064277 and R01 CA90899.

Abbreviations

- BBD

benign breast disease

- CI

confidence interval

- D-loop

displacement loop

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- mtSSB

mitochondrial single-stranded DNA-binding protein

- np

nucleotide positions

- OR

odds ratio

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement:The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Reference List

- 1.Andrews RM, Kubacka I, Chinnery PF, Lightowlers RN, Turnbull DM, Howell N. Reanalysis and revision of the Cambridge reference sequence for human mitochondrial DNA. Nat.Genet. 1999;23:147. doi: 10.1038/13779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianchi NO, Bianchi MS, Richard SM. Mitochondrial genome instability in human cancers. Mutat.Res. 2001;488:9–23. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richard SM, Bailliet G, Paez GL, Bianchi MS, Peltomaki P, Bianchi NO. Nuclear and mitochondrial genome instability in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4231–4237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki M, Toyooka S, Miyajima K, Iizasa T, Fujisawa T, Bekele NB, Gazdar AF. Alterations in the mitochondrial displacement loop in lung cancers. Clin.Cancer Res. 2003;9:5636–5641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lievre A, Chapusot C, Bouvier AM, Zinzindohoue F, Piard F, Roignot P, Arnould L, Beaune P, Faivre J, Laurent-Puig P. Clinical value of mitochondrial mutations in colorectal cancer. J.Clin.Oncol. 2005;23:3517–3525. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gille JJ, Joenje H. Cell culture models for oxidative stress: superoxide and hydrogen peroxide versus normobaric hyperoxia. Mutat.Res. 1992;275:405–414. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(92)90043-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan DJ, Bai RK, Wong LJ. Comprehensive scanning of somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:972–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu W, Qin W, Bradley P, Wessel A, Puckett CL, Sauter ER. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in breast cancer tissue and in matched nipple aspirate fluid. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:145–152. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tseng LM, Yin PH, Chi CW, Hsu CY, Wu CW, Lee LM, Wei YH, Lee HC. Mitochondrial DNA mutations and mitochondrial DNA depletion in breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes.Cancer. 2006;45:629–638. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polyak K, Li Y, Zhu H, Lengauer C, Willson JK, Markowitz SD, Trush MA, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Somatic mutations of the mitochondrial genome in human colorectal tumours. Nat.Genet. 1998;20:291–293. doi: 10.1038/3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao YT, Shu XO, Dai Q, Potter JD, Brinton LA, Wen W, Sellers TA, Kushi LH, Ruan Z, Bostick RM, Jin F, Zheng W. Association of menstrual and reproductive factors with breast cancer risk: results from the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study. Int.J.Cancer. 2000;87:295–300. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20000715)87:2<295::aid-ijc23>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnitt S CJ. Pathology of benign breast disorders. In: Harris JR, editor. Diseases of the breast. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. pp. 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shu XO, Jin F, Dai Q, Shi JR, Potter JD, Brinton LA, Hebert JR, Ruan Z, Gao YT, Zheng W. Association of body size and fat distribution with risk of breast cancer among Chinese women. Int.J.Cancer. 2001;94:449–455. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yasukawa T, Yang MY, Jacobs HT, Holt IJ. A bidirectional origin of replication maps to the major noncoding region of human mitochondrial DNA. Mol.Cell. 2005;18:651–662. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takamatsu C, Umeda S, Ohsato T, Ohno T, Abe Y, Fukuoh A, Shinagawa H, Hamasaki N, Kang D. Regulation of mitochondrial D-loops by transcription factor A and single-stranded DNA-binding protein. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:451–456. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu M, Zhou Y, Shi Y, Ning L, Yang Y, Wei X, Zhang N, Hao X, Niu R. Reduced mitochondrial DNA copy number is correlated with tumor progression and prognosis in Chinese breast cancer patients. IUBMB.Life. 2007;59:450–457. doi: 10.1080/15216540701509955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fish J, Raule N, Attardi G. Discovery of a major D-loop replication origin reveals two modes of human mtDNA synthesis. Science. 2004;306:2098–2101. doi: 10.1126/science.1102077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park KS, Chan JC, Chuang LM, Suzuki S, Araki E, Nanjo K, Ji L, Ng M, Nishi M, Furuta H, Shirotani T, Ahn BY, Chung SS, Min HK, Lee SW, Kim JH, Cho YM, Lee HK. A mitochondrial DNA variant at position 16189 is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Asians. Diabetologia. 2008;51:602–608. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-0933-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen W, Ren Z, Shu XO, Cai Q, Ye C, Gao YT, Zheng W. Expression of cytochrome P450 1B1 and catechol-O-methyltransferase in breast tissue and their associations with breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol.Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:917–920. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, Lingle WL, Degnim AC, Ghosh K, Vierkant RA, Maloney SD, Pankratz VS, Hillman DW, Suman VJ, Johnson J, Blake C, Tlsty T, Vachon CM, Melton LJ, III, Visscher DW. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N.Engl.J.Med. 2005;353:229–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silvera SA, Rohan TE. Benign proliferative epithelial disorders of the breast: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Breast Cancer Res.Treat. 2008;110:397–409. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9740-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]