Abstract

Objective

To describe role and involvement of Life End Information Forum (LEIF) physicians in end-of-life care decisions and euthanasia in Flanders.

Study Design

All 132 LEIF physicians in Belgium received a questionnaire inquiring about their activities in the past year, and their end-of-life care training and experience.

Principal Findings

Response rate was 75 percent. Most respondents followed substantive training in end-of-life care. In 1 year, LEIF physicians were contacted 612 times for consultations in end-of-life decisions, of which 355 concerned euthanasia requests eventually resulting in 221 euthanasia cases. LEIF physicians also gave information about various end-of-life issues (including palliative care) to patients and colleagues.

Conclusions

LEIF physicians provide a forum for information and advice for physicians and patients. A similar health service providing support to physicians for all end-of-life decisions could also be beneficial for countries without a euthanasia law.

Keywords: Consultation, euthanasia, end-of-life decisions

In 2002, both Belgium and the Netherlands enacted a law on euthanasia, that is, the deliberate ending of a patient's life by a physician at the patient's request (Law Concerning Euthanasia 2002; Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide [Review Procedures] Act 2002; Deliens and van der Wal 2003;). Euthanasia is a medical practice requiring great care. Therefore, the mandatory consultation of an independent physician was incorporated into the Dutch and Belgian laws as one of the procedural criteria of due care. This independent physician has to read the medical file, consult both attending physician and patient, and make a written report. In the Netherlands, where a long history of jurisprudence concerning the practice of euthanasia preceded its legalization (Royal Dutch Medical Association [KNMG] Euthanasia Workgroup 1975; Board of the Royal Dutch Medical Association 1996; Dillmann et al. 1997; Weyers 2001; Smets et al. 2009;), the Royal Dutch Medical Association initiated a nation-wide consultation project for euthanasia in 1999 called “Support and Consultation for Euthanasia in the Netherlands” (SCEN). Physicians who received a euthanasia request could call a central number and request a formal consultation by an assigned consultant physician.

The Belgian euthanasia law was not preceded by a history of jurisprudence and the legislature did not provide a consultation project like in the Netherlands (Onwuteaka-Philipsen and van der Wal 2001a). In 2003, a group of individuals with experience in end-of-life care used SCEN as a model to create a similar initiative for the Flemish-speaking community in Belgium (Quarterly Right to Die with Dignity 2004; Distelmans, Bauwens, and Destrooper 2006; Distelmans 2008;). They founded “Life End Information Forum” (LEIF) intending not only to help physicians confronted with euthanasia requests in finding a specifically trained, accessible, and independent physician for a formal consultation as required by the euthanasia law, but also to offer a wide information and support forum for both professional caregivers and patients who have questions about the end of life (including palliative care). The law does not compel attending physicians to consult via LEIF, which is to date a voluntary association, funded by the government. If they do so, they are not obliged to first contact the LEIF secretariat, which is staffed by the coordinator, a social nurse, and a pharmacist. LEIF physicians are offered five training modules (24 hours in total) on several end-of-life decisions, the practice of euthanasia, and related communication, and are encouraged to attend biannual “intervision” groups to discuss and evaluate practices.

In Belgium, the frequency of prior consultation of colleague physicians in medical end-of-life practices has been studied (Deliens, Mortier, and Bilsen 2000; van der Heide et al. 2003; Cohen et al. 2007;), but unlike in the Netherlands (Onwuteaka-Philipsen and van der Wal 2001b; Jansen-van der Weide, Onwuteaka-Philipsen, and van der Wal 2004; Jansen-van der Weide, Onwuteaka-Philipsen, and van der Wal 2007; Royal Dutch Medical Association 2007;) no studies have looked at the characteristics of the consulting or consulted physician and of the consultation itself or have described and evaluated LEIF. This paper, therefore, aims to describe characteristics of LEIF physicians and their activities concerning consultation, information, and advice in end-of-life decisions during a 1-year period, and provide insight into their involvement in euthanasia cases. We will address three research questions: (1) What are the characteristics of LEIF physicians and what training and experience with end-of-life care do they have? (2) What kind of requests do LEIF physicians receive, by whom and via which route? (3) What is the actual involvement of LEIF physicians in euthanasia cases?

METHODS

Data Collection

A descriptive retrospective study was conducted. The LEIF secretariat identified 132 physicians who—at the time of the study (May–September 2008)—had followed at least two modules of the LEIF training and were hence considered to function actively as LEIF physicians. The LEIF secretariat sent a mail questionnaire with a unique serial number to all LEIF physicians, requesting them to return it to the researchers, who communicated to the LEIF secretariat which serial numbers had been received, hence enabling the sending of up to three reminders in cases of nonresponse. The survey was done according to the Total Design Method (Dillman 1991) (questionnaire kept fairly short, cognitive pretesting, prenotice letter signed by the director of LEIF, individually addressed mailings, prepaid return envelope, three reminders). The anonymity of the physicians was guaranteed as the researchers removed the serial numbers from the questionnaires, had no access to the database of the LEIF secretariat with the personal details of all LEIF physicians, and the LEIF secretariat had no access to the completed questionnaires. The study received approval from the ethics committee of the University Hospital of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire drew partly on the yearly Dutch registration form of the activities of SCEN physicians (Royal Dutch Medical Association 2007) and on the questionnaires of the SCEN evaluation study (Jansen-van der Weide, Onwuteaka-Philipsen, and van der Wal 2007). The first part asked about the physician's sociodemographics and end-of-life care experience and training. The second part asked about their activities as LEIF physicians during the past year regarding (1) consultation in euthanasia requests; (2) consultation in other end-of-life decisions (including palliative care) such as nontreatment decisions and terminal sedation; and (3) the provision of information to physicians, patients and their family, and others. Regarding the consultations in cases of requests for euthanasia, the LEIF physicians were asked in more detail about their involvement in the decision-making process.

RESULTS

Response

Four physicians were no longer active as LEIF physicians. Of the remaining 128, 96 (75 percent) participated in the study. Analyses for nonresponse bias showed no significant differences for gender, age, province, specialty, and number of modules from the LEIF training program followed.

Characteristics of LEIF Physician

Almost 65 percent of them were 50 years or older (not in table). The age group 30–39 years is underrepresented compared with all physicians in Flanders and Brussels (p<.01). LEIF physicians have a proportional distribution over all provinces of Flanders. Of all respondents, 73 percent are general practitioners (GPs), significantly more than in the total population of physicians in the regions studied (p<.01).

End-of-Life Care Training and Experience

About 73 percent of respondents followed some education in end-of-life care additional to the LEIF training (Table 1). They attended on average four seminars (SD=11.5) and 9 entire study days (SD=45.4) on end-of-life care (not in table). Almost 41 percent followed the 30-hour postgraduate interuniversity training in palliative care. A quarter are part of a hospital or home care multidisciplinary palliative care team (Table 1).

Table 1.

End-of-Life Care Training and Experience of Life End Information Forum (LEIF) Physicians (N=96)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Additional training in end-of-life care | 69 (73.4) |

| Postgraduate studies in palliative care* | 39 (40.6) |

| Study days in end-of-life care | 48 (50.0) |

| Seminars in end-of-life care | 52 (54.2) |

| Training weekends on end-of-life care and bereavement … | 17 (17.7) |

| End-of-life care training during internship | 8 (8.3) |

| LEIF training: number of modules followed† | |

| 2 modules | 12 (12.5) |

| 3 modules | 16 (16.7) |

| 4 modules | 26 (27.1) |

| 5 modules | 42 (43.8) |

| Member of palliative team‡ | 25 (26.0) |

| Number of incurably ill patients cared for at their end of life in the past year | |

| <5 patients | 42 (43.8) |

| 5–9 patients | 21 (21.9) |

| 10–19 patients | 17 (17.7) |

| ≥20 patients | 13 (13.5) |

Notes. The numbers mentioned are N physicians (%).

The postgraduate studies in palliative care are organized in cooperation with several Flemish universities and the Federation of Palliative Care Flanders. This course of 30 hours training in 1 year is for physicians.

Data were provided by the LEIF secretariat. The maximum number of modules in the LEIF training is 5. We chose to select the physicians who followed at least two modules for this study because this is the minimum being requested for practicing as LEIF physician.

A palliative team in Belgium is a multidisciplinary team consisting of one or more physicians, nurses, psychologist, and other paramedics that is active in a hospital setting or at home.

Over 30 percent cared for 10 or more terminal patients during the past year. This differed per specialty: GPs had care of, on average, 6 patients and specialists of 72 patients.

About 5 percent were not part of a palliative team, had not attended any kind of training in end-of-life care besides the LEIF courses, and had not cared for any terminally ill patients in the last year.

Requests for Consultation and Information

Nearly three quarters of all responding LEIF physicians had been contacted for consultation as a second physician in a euthanasia request in the past year, on average almost four times per LEIF physician. The majority (63.5 percent) were contacted directly by the attending physician (Table 2). Fewer were contacted by the LEIF secretariat (35.4 percent), by the patient (17.7 percent), or via another route (e.g., family of patient, psychologist: 5.2 percent). Almost 27 percent had not been contacted for consultation in euthanasia requests during the past year. Having been contacted for consultation was not related to gender, age, region, specialty, and number of LEIF training modules attended, but physicians with additional education in end-of-life care were contacted more often than those without (p=.03) (not in table).

Table 2.

Type and Frequency of Initial Consultation Requests to Life End Information Forum (LEIF) Physicians (N=96) during a 1-Year Period

| Number of LEIF Physicians Who Were Contacted (%)* | Average per LEIF Physician (SD)† | |

|---|---|---|

| Consultation | ||

| For consultation in euthanasia requests‡ | 70 (72.9) | 3.70 (4.93) |

| Contacted by LEIF secretariat | 34 (35.4) | 0.94 (1.71) |

| Contacted directly by attending physician | 61 (63.5) | 2.28 (3.63) |

| Contacted directly by patient | 17 (17.7) | 0.28 (0.75) |

| Contacted in other way | 5 (5.2) | 0.07 (0.33) |

| For consultation in other ELDs | 28 (29.2) | 2.12 (5.06) |

| Nontreatment decision | 16 (17.4) | 1.03 (3.05) |

| Continuous sedation until death | 15 (17.4) | 0.54 (1.81) |

| Alleviation of pain and symptoms | 24 (26.1) | 1.12 (3.13) |

| Life-ending act where patient consent is no longer possible | 5 (5.4) | 0.10 (0.49) |

| Information about§ | ||

| Legal procedure euthanasia | 78 (90.7) | 12.51 (2.18) |

| By physicians | 62 (70.1) | 3.72 (6.32) |

| By patients | 59 (68.6) | 7.33 (13.9) |

| By others¶ | 18 (20.9) | 1.56 (3.95) |

| Living will arrangement | 75 (87.2) | 12.21 (1.85) |

| By physicians | 39 (45.3) | 2.93 (6.99) |

| By patients | 63 (73.3) | 7.63 (12.38) |

| By others¶ | 19 (22.1) | 1.65 (4.43) |

| Palliative care | 55 (64) | 10.79 (1.87) |

| By physicians | 28 (32.6) | 3.41 (11.98) |

| By patients | 47 (54.7) | 6.20 (9.96) |

| By others¶ | 13 (15.1) | 1.19 (3.36) |

| Practical performance of euthanasia | 54 (62.8) | 4.71 (0.87) |

| By physicians | 46 (53.5) | 2.62 (6.02) |

| By patients | 30 (34.9) | 1.57 (3.59) |

| By others¶ | 6 (7.0) | 0.52 (2.47) |

| The LEIF association | 50 (58.1) | 6.64 (1.18) |

| By physicians | 40 (46.5) | 2.87 (6.59) |

| By patients | 31 (36.0) | 2.85 (6.17) |

| By others¶ | 10 (11.6) | 0.92 (2.70) |

| Other medical end-of-life decisions besides euthanasia | 47 (54.7) | 6.41 (1.16) |

| By physicians | 25 (29.1) | 1.79 (4.22) |

| By patients | 36 (41.9) | 3.79 (8.14) |

| By others¶ | 9 (10.5) | 0.83 (2.89) |

Percentages of physicians are calculated for total responding in each category.

Average number of demands by physician for all responding physicians (standard deviation of average number).

Multiple responses possible.

Ten missing observations.

Others can be anyone (except colleague physicians, patients, and patients' family) who asks the LEIF physician for information, for example, the physician's entourage, careworkers, etc.

ELDs, end-of-life decisions.

Almost 30 percent of LEIF physicians were contacted for consultation in end-of-life decisions other than euthanasia, on average twice per LEIF physician per year (Table 2). They reported 103 consultations for possibly life-shortening alleviation of symptoms and pain, 95 within the context of a nontreatment decision, 50 for continuous deep sedation until death, and 9 for life-ending acts with no explicit request from the patient (not in table).

About 86 percent were contacted to provide information. In 1 year they received 2,518 requests for information by patients, mostly about living wills (n=656), the legal procedure of euthanasia (n=623) or palliative care (n=533), and 1,491 requests by physicians, of which 37 percent (n=545) were about the legal procedure or practical performance of euthanasia (not in table).

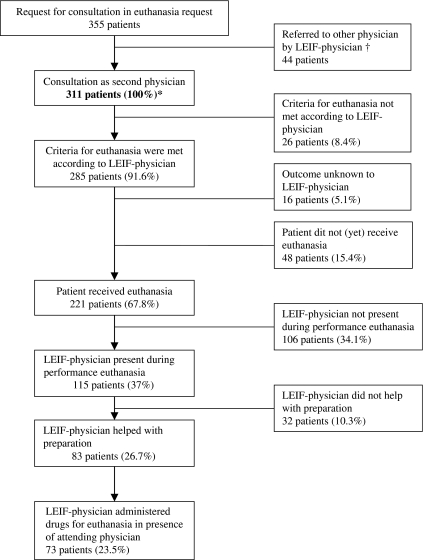

Involvement of LEIF Physicians in Euthanasia Cases

The responding LEIF physicians were asked to consult as a second physician in 355 cases of euthanasia requests (Figure 1). Of these, 311 resulted in an actual consultation with the LEIF physician. In 285 cases (91.6 percent of the consultations) the LEIF physician evaluated all due care criteria to have been met and 221 (67.8 percent) resulted in euthanasia. LEIF physicians were present at the time of euthanasia in 115 cases (37 percent) and helped with the preparation in 83 (26.7 percent). In 73 (23.5 percent) cases, they administered the drugs themselves in the presence of the attending physician. In the open question at the end of the questionnaire, some physicians reported reasons for performing the euthanasia themselves, for example, because the attending physician did not want to do it for personal or medico-technical reasons.

Figure 1.

Involvement of Life End Information Forum (LEIF) Physicians in Euthanasia Cases

*The numbers mentioned in the figure are N patients and percentages from total consultations N=311.

†Reasons for referring to another physician could be that the LEIF physician was not available at the time of contact, that the LEIF physician considered him/herself not independent from the attending physician, etc.

At the level of physicians, 69.8 percent of the LEIF physicians did at least one consultation as a second or third physician in a euthanasia request during the past 12 months. One-third had been present at least once at the time of euthanasia, 38.5 percent had helped at least once with the preparation of the act, and 27.1 percent had administered the drugs for euthanasia at least once.

DISCUSSION

This study describes the characteristics and activities of the physicians of the LEIF, which was initiated as a specialized supporting health service for euthanasia and other end-of-life decision making in Flanders. We found that 73 percent are GPs and nearly all LEIF physicians have relevant experience in end-of-life care, whether in the form of training (73 percent), being a member of a palliative team (26 percent), or having cared for terminally ill patients within the past year (90 percent). An important part of their work consists of giving information about a wide spectrum of topics in end-of-life care to health care providers as well as to patients and their families. They provide consultation in euthanasia cases but also in other end-of-life decisions. For consultation as a second physician in euthanasia requests most of them were contacted directly by the attending physician, but 27 percent were not contacted at all over a 1-year period. In this period, LEIF physicians were involved as consultants in 311 euthanasia requests resulting in 221 performed euthanasia cases and administered the euthanasia drugs in 23 percent of cases.

This is the first study to describe the Belgian consultation service for euthanasia. The response rate of 75 percent enhances the generalizability of the results for the whole population of LEIF physicians in Flanders, Belgium. Limitations of the study are that due to the low absolute number of trained LEIF physicians, the absolute number included—and hence the statistical power—is rather low, while the retrospective design of this study may have caused recall bias, which we can expect to apply in particular to the number of contacts for provision of information on end-of-life care. This study does not include any expert evaluation of the quality of the consultations and the results are entirely self-reported.

An important finding is that LEIF physicians seem to be well educated in end-of-life care beyond the LEIF training, which itself covers issues on palliative care as well as on euthanasia (Distelmans 2008). Compared with physicians in Belgium from specialties that are more likely to provide end-of-life care, the percentage of LEIF physicians who attended a postgraduate medical course in palliative care is much higher (Lofmark et al. 2006). A quarter were also actually members of a palliative care team. Some authors think that consulting another physician in euthanasia cases is not necessarily a good safeguard of careful practice if the consultant has no competence in end-of-life care (Pollard 2001; Broeckaert and Janssens 2002;). While the Belgian law does not specify that the second physician should have such a competence, it does specify that the possibilities of palliative care need to be discussed with the patient. It seems therefore preferable that physicians who work for such a health service are well educated in end-of-life care, which is the case with LEIF physicians, and also have significant experience. As LEIF physicians seem not to have significantly more clinical experience than average physicians (Van den Block 2008), this could be a possible weakness, although their functioning as consultants will increase their experience. This can benefit a careful euthanasia practice in which the options of palliative care and the choice of euthanasia are well balanced, contributing to the quality of end-of-life decision making in general.

Our results show that the LEIF secretariat is often bypassed as LEIF physicians are contacted directly by the attending physician more often than via the secretariat. An advantage of this is accessibility. However, the attending physicians may always call the same consultant (REF; Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al. 1999), which might be detrimental to independence. The Belgian and Dutch euthanasia laws state that the consulting physician should be independent from patient and attending physician but what is meant by independence is not specified (Law Concerning Euthanasia 2002; Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide [Review Procedures] Act 2002;). The intention of the law is that the consultant should always be able to formulate advice independently from the views of the attending physician and the patient. A consultant service with strict guidelines for contact through a central point, as is the case in the Netherlands, can reduce the chances that a physician will use the same consultant several times. Above that, it can ensure the building-up of experience for all trained consultants.

By sometimes being present when euthanasia takes place and administering the drugs themselves, the involvement of LEIF physicians goes further than officially outlined by LEIF. As we learned from the commentaries in the open-ended questions, this happens for psychological reasons, for example, the unwillingness of the attending physician to administer the drugs, and for didactical reasons, for example, if the attending physician is inexperienced or unfamiliar with the drugs used. The Belgian law does not specify that the attending physician should perform the act of euthanasia (it can be done by any physician), but the roles between the attending physician and the consultant are not intended to be reversed when the former does not want to perform euthanasia (Law Concerning Euthanasia 2002).

The numbers of notified euthanasia cases in Flanders (Federale Controle—en Evaluatiecommissie 2007) combined with our results suggest that LEIF physicians are involved in more than half of all euthanasia cases in Flanders, assuming that these cases were notified (Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al. 2007). This further stresses the potential importance of a provision such as LEIF and the need for further research to provide insight into the quality of consultations. For other countries considering a law on life-ending on request, a service like LEIF could be beneficial, albeit preferably with strict guidelines concerning contact and consultation procedures. It is also important that the consultants have sufficient education and experience in end-of-life care, although there is no standard as to how much would be sufficient. Providing a service like LEIF where help in end-of-life care issues is freely available can be valuable in any country, regardless of the existence of a euthanasia law, and can contribute toward guaranteeing the competence necessary to the provision of accurate information and support in the range of difficult care situations that can arise at the end of life.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This study is part of the “Monitoring Quality of End-of-Life Care (MELC) Study,” a collaboration between the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Ghent University, Antwerp University, the Scientific Institute of Public Health, Belgium, and VU University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. This study is supported by a grant from the Institute for the Promotion of Innovation by Science and Technology in Flanders (Instituut voor de aanmoediging van Innovatie door Wetenschap en Technologie in Vlaanderen) (SBO IWT nr. 050158).

We would like to thank all LEIF physicians for their participation in this study and the LEIF secretariat (especially P. Destrooper and K. Van de Gaer) for providing their assistance in the mailing procedure of the questionnaires.

Disclosure: The fifth author, W. Distelmans, is the present director of the LEIF project. He contributed to the organization of the survey and the interpretation of the data, but he did not have an influence on the decision as to which data would be presented.

Disclaimers: None.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

REFERENCES

- Board of the Royal Dutch Medical Association. “Vision on Euthanasia” Euthanasia in the Netherlands. 5th Edition. Utrecht: Board of the Royal Dutch Medical Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Broeckaert B, Janssens R. Palliative Care and Euthanasia. Belgian and Dutch Perspectives. Ethical Perspectives. 2002;9(2–3):156–75. doi: 10.2143/ep.9.2.503854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Bilsen J, Fischer S, Lofmark R, Norup M, van der Heide A, Miccinesi G, Deliens L and on behalf of the EURELD Consortium. End-of-Life Decision-Making in Belgium, Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland: Does Place of Death Make a Difference? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2007;61(12):1062–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.056341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deliens L, Mortier F, Bilsen JEA. End-of-Life Decisions in Medical Practice in Flanders, Belgium: A Nationwide Survey. Lancet. 2000;356(9244):1806–11. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deliens L, van der Wal G. The Euthanasia Law in Belgium and the Netherlands. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1239–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14520-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman D. The Design and Administration of Mail Surveys. Annual Review of Sociology. 1991;17:225–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dillmann R, Krug C, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Van der Wal G, Wigersma L. “Support and Consultation in Cases of Euthanasia in Amsterdam.” Medisch Contact, 52: 743 (in Dutch)

- Distelmans W. Een Waardig Levenseinde. Vierde Geactualiseerde Druk. Antwerpen; Belgium: Houtekiet; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Distelmans W, Bauwens S, Destrooper P. Life End Information Forum-Physicians (LEIFartsen): Improvement of Communication Skills in End-of-Life Issues among Physicians. Psycho Oncology. 2006;15(2, Suppl):226–7. [Google Scholar]

- Federale Controle—en Evaluatiecommissie. Derde Verslag Aan De Wetgevende Kamers. 2007. Federal Control and Evaluation Committee Euthanasia. Third Report to Parliament (2006–2007) (in Dutch and French)

- Jansen-van der Weide M, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, van der Wal G. Implementation of the Project ‘Support and Consultation on Euthanasia in the Netherlands’ (SCEN) Health Policy. 2004;69(3):365–73. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen-van der Weide M. Quality of Consultation and the Project ‘Support and Consultation on Euthanasia in the Netherlands’ (SCEN) Health Policy. 2007;80(1):97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law Concerning Euthanasia. May 28. 2002. “Wet Betreffende Euthanasie, 28 Mei 2002” Belgisch Staatsblad 2002 juni 2002 (Belgian official collection of the laws June 22 2002) 2002009590.

- Lofmark R, Mortier F, Nilstun T, Bosshard G, Cartwright C, Van der Heide A, Norup M, Simonato L, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. Palliative Care Training: A Survey of Physicians in Australia and Europe. Journal of Palliative Care. 2006;22(2):105–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Gevers J, van der Heide A, van Delden J, Pasman R, Rietjens J, Rurup M, Buiting H, Hanssen-de Wolf J, van der Maes P. Evaluatie Wet Toetsing Levensbeeindiging Op Verzoek En Hulp Bij Zelfdoding. Den Haag: Zon/Mw; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, van der Wal G. Support and Consultation for General Practitioners Concerning Euthanasia: The SCEA Project. Health Policy. 2001a;56(1):33–48. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(00)00128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. A Protocol for Consultation of Another Physician in Cases of Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2001b;27(5):331–7. doi: 10.1136/jme.27.5.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, van der Wal G, Kostense P, van der Maas P. Consultants in Cases of Intended Euthanasia or Physician-Assisted Suicide. Medical Journal of Australia. 1999;170(8):360–3. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb139166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard B. Can Euthanasia Be Safely Legalized? Palliative Medicine. 2001;15(1):61–5. doi: 10.1191/026921601668201749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarterly Right to Die with Dignity. “Kwartaalblad Recht Op Waardig Sterven.” June: 18–19 (in Dutch)

- Royal Dutch Medical Association. “Spiegelinformatie Scen 2006” (in Dutch, KNMG)

- Royal Dutch Medical Association (KNMG) Euthanasia Workgroup. “Discussion Note of the Euthanasia Workgroup [Discussienota Van De Werkgroep Euthanasie].” Medisch Contact, 30: 9 (in Dutch)

- Smets T, Bilsen J, Cohen J, Rurup M, De Keyser E, Deliens L. The Medical Practice of Euthanasie in Belgium and the Netherlands: Legal Notification, Control and Evaluation Procedures. Health Policy. 2009;90(2):181–7. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide (Review Procedures) Act April 1, 2002. “Wet Toetsing Levensbeeindiging Op Verzoek En Hulp Bij Zelfdoding 1 April, 2002.”.

- Van den Block L. End-of-Life Care and Medical Decision-Making in the Last Phase of Life. Brussels, Belgium: VUB Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- van der Heide A, Deliens L, Faisst K, Nilstun T, Norup M, Paci E, van der Wal G, van der Maas P. End-of-Life Decision-Making in Six European Countries: A Descriptive Study. Lancet. 2003;362(9381):345–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyers H. Euthanasia: The Process of Legal Change in the Netherlands. The Making of the ‘Requirement of Careful Practice’. In: Klijn A, Otlowski M, Trappenburg M, editors. Regulating Physician-Negotiated Death. Gravenhage, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2001. pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.