Abstract

Background

The neural substrates regulating sensorimotor gating in rodents are studied in order to understand the basis for gating deficits in clinical disorders such as schizophrenia. N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) infusion into the ventral temporal lobe, including caudal parts of the ventral hippocampal region and amygdala, has been shown to disrupt sensorimotor gating in rats, as measured by prepulse inhibition of startle (PPI). One working model is that reduced PPI after infusion of NMDA into this region is mediated via its efferents to ventral forebrain structures, i.e., medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens. Yet, PPI-disruptive effects persist after lesions of the precommissural fornix, the principal output pathway of the hippocampal formation. Here, we aimed to characterize non-fornical forebrain projections from this region that might mediate the PPI-disruptive effects of the ventral temporal lobe.

Methods

Electrolytic lesions of the precommissural fornix in male Sprague Dawley rats were followed by infusions of fluorogold into the medial prefrontal cortex or by infusions of biotinylated dextan amine into the ventral temporal lobe.

Results

Projections from the ventral subiculum and CA1 regions of the ventral hippocampus to the medial prefrontal cortex and accumbens core and shell were interrupted by fornix lesions. Projections to the medial prefrontal cortex and accumbens from other regions of the ventral temporal lobe, particularly the lateral entorhinal cortex and the embedded olfactory and vomeronasal parts of the caudal amygdala, survived fornix lesions. These additional projections coursed rostrally through the amygdala and emerged via the stria terminalis, interstitial nuclei of the posterior limb of the anterior commissure, and the ventral amygdalofugal pathway.

Conclusions

PPI-regulatory portions of the ventral temporal lobe innervate the accumbens and medial prefrontal cortex via multiple routes. It remains to be determined which of these non-fornical projections may be responsible for the persistent regulation of PPI after fornix lesions.

Keywords: nucleus accumbens, prefrontal cortex, prepulse inhibition, schizophrenia, sensorimotor gating

INTRODUCTION

Prepulse inhibition (PPI) is an operational measure of sensorimotor gating, in which a weak lead stimulus inhibits the motor response to an intense, startling stimulus (Graham 1975). PPI in laboratory animals has been used to understand the neural and genetic basis for PPI deficits in several neuropsychiatric disorders. For example, PPI is potently regulated by portions of the ventral hippocampal region (VH) in rats, and this regulation has been studied to understand the potential contribution of hippocampal pathology to PPI deficits in schizophrenia patients (Braff et al. 1978; cf. Swerdlow et al. 2008). Using the terminology of Witter and Amaral (2004), the “hippocampal region” consists of the hippocampal formation (dentate gyrus, hippocampus (CA1, CA2, CA3), subiculum) and parahippocampal region (entorhinal, perirhinal, and postrhinal cortices, presubiculum, parasubiculum).

Because PPI is impaired in several brain disorders, substantial effort has been dedicated towards understanding the efferent projections from the VH to ventral forebrain targets - including the nucleus accumbens (NAC) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) - that might mediate the loss of PPI after intra-VH infusion of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) (Wan et al. 1996). Based on the potent regulation of PPI by the NAC (cf. Swerdlow et al. 2001a, 2008) and the known interplay of the VH and NAC in the regulation of other behaviors in rats (e.g., Mogenson and Nielsen, 1984), a seemingly simple explanation was that the PPI-regulatory effects of the VH were mediated by their projections to the NAC via the fimbria/fornix, the principal source of fibers from the hippocampal formation. However, this simple model was incompatible with our findings that the PPI-disruptive effects of intra-VH NMDA infusion remained intact after transection of the precommissural fornix (Swerdlow et al. 2004), but were opposed by electrolytic lesions of the mPFC (Shoemaker et al. 2005). Clearly, these findings forced a reassessment of the simplest model whereby the ventral forebrain might mediate the PPI-disruptive effects of intra-NMDA infusion: any such role of the ventral forebrain must rely on the presence of non-fornical projections of the ventral temporal lobe.

While there are a wealth of studies that show, in some instances, strong projections to portions of mPFC from parahippocampal regions, such as entorhinal cortex (reviewed in Witter and Amaral, 2004), and from adjacent structures of the caudal amygdala (reviewed in de Olmos, et al., 2004), the actual course of the fibers that connect these structures to mPFC is less clear. The goal of the present study was to characterize the non-fornical pathways by which the VH and its neighboring amygdaloid structures might access medial forebrain structures. Once characterized, these non-fornical projections could be targeted to determine which, if any, mediate the loss of PPI after intra-NMDA infusion.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Experimental Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (total n = 58; 225–250 g; Harlan, Livermore) were housed in groups of 2–3 and maintained on a reversed 12-h light/dark schedule with ad libitum food and water. Behavioral testing was performed during the dark phase of the cycle. Rats were handled individually within 2 days of arrival. All surgery occurred between 7 and 14 days after arrival. Maximal care was taken to minimize animal suffering and reduce the number of animals used. All experiments conformed to guidelines of the National Institutes of Health for the use of animals in biomedical research (NIH Publication No. 80-23) and were approved by the Animal Subjects Committee at the University of California, San Diego (Protocol S01221).

Surgical Preparations

Wherever possible, methods for tracer infusion and lesions closely mimicked those for drug infusion in our published behavioral studies. Rats were administered 0.1 ml atropine (Vedco, 0.054 mg/ml) subcutaneously 15–30 min prior to being anesthetized using sodium pentobarbital (Nembutal, Abbot, 60 mg/kg, i.p.), and were then placed in a Kopf stereotaxic instrument in the flat-brain position (tooth bar 3.3 mm below the interaural line). In rats used for retrograde tract-tracing, fluorogold (hydroxystilbamidine methanesulfonate, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA) was infused (2% in saline, 0.2 µl /5 min) into the ventral mPFC (A/P: +3.2, M/L: ±0.7, D/V: −5.5; n = 10). In rats used for anterograde tract-tracing (n = 29), biotinylated dextran amine (BDA – lysine fixable, 10K MW, Invitrogen) was infused (5% in saline, 0.2 µl / 5 min) unilaterally into the ventral subicular (VS) or lateral entorhinal (LEnt) areas of the VH (A/P: −6.0, M/L: ±4.4 [VS] or ±5.4 [LEnt], D/V: −8.1). Infusions were made using a Hamilton micro-syringe pump (Razel Scientific Instruments) attached to polyethylene tubing and a 30 GA infusion needle identical to that used for drug delivery in our behavioral studies. The needle was lowered to the D/V coordinate, and then raised 0.5 mm to create a pocket to accept the tracer and reduce the likelihood of tracer backflow along the injector-needle tract. In some rats, unilateral electrolytic lesions of the precommisural fornix (A/P: −1.6, L: ±1.7, D/V: −5.0) were made prior and ipsilateral to tracer infusion, by twice passing a 2.0 mA × 15 s current (Ugo Basile, 3500 Lesion Producing Device, Varese, Italy). The remaining rats received no lesion, i.e., no puncture of the brain or skull. A subset of the lesioned rats (n = 6) received bilateral infusions of BDA with unilateral electrolytic lesions of the fornix. An additional 16 rats were tested for disruption of PPI by bilateral infusion of NMDA (0.8 µg / 0.5 µl) at coordinates identical to those used for the VS (n = 8) and LEnt (n = 8) BDA infusions, as per our published methods (Swerdlow et al. 2001b), to confirm the appropriateness of these BDA targets.

Histology

After surgery, a 2-week postoperative period was used to allow for proper uptake and transport of the tracer. Rats were then administered a pentobarbital overdose and perfused with a rinsing solution (0.9% NaCl solution, 1 min), followed by fixative (4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 2.5 min). Brains were removed after 1 h and immersed in fixative for 24 h at 4°C, trimmed in the coronal plane posterior to the midbrain, and post-fixed in cold fixative containing 30% sucrose for 3 days. Brains were sectioned (40 µm) on a freezing stage sliding microtome (Leica, SM 2000R). Sections were collected in tris-buffered saline (TBS, pH 7.4) for subsequent fluorogold or BDA histochemistry (below), and Nissl-staining.

BDA Histochemistry

Sections were first exposed to 0.525% H2O2 in TBS for 20 min, to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. After several rinses, tissue was exposed overnight to an ABC reagent (Vectastain, PK-6100 Standard Elite Kit, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA; diluted 1:100) in TBS with 0.33% Triton X-100. Sections were rinsed and incubated in a diaminobenzidine/NiCl solution (Vector Labs SK-4100 kit) for 10 min without and 10 min with H2O2. Sections were rinsed in ice-cold TBS to terminate the reaction, mounted immediately onto microscope slides and air-dried.

Fluorogold Histochemistry

Sections were exposed to H2O2 in TBS as above and placed in a blocking solution (10% horse serum (Invitrogen) + 0.33% Triton-X in TBS) for 2 h, then exposed to a rabbit anti-fluorogold antibody (AB153, Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA; diluted 1:8000) dissolved in the blocking solution overnight. The next day, tissue was incubated with a biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA; diluted 1:800) dissolved in blocker for 4 h, and exposed overnight to the ABC reagent in TBS with 0.33% Triton X as described above. The remaining steps were as described above for BDA histochemistry.

Microscopy and Histological Analysis

For the anterograde tract-tracing cases, the extent of fornix lesions was assessed according to the amount of downstream labeling that occurred in the postcommissural fornix. Retrograde cases were assessed according to amount of somatic CA1/VS labeling, as well as the observed damage to the fornix. BDA infusion sites were demarcated according to the region most densely labeled and the distribution of cell bodies that had taken up the BDA. Fluorogold infusion sites were demarcated solely by the region of dense fluorogold deposit, excluding contiguous areas of retrogradely labeled cell bodies that had actively transported the tracer from the injection site. Micrographs were obtained with a Polaroid (DMC) digital microscope camera and software attached to a Leitz Laborlux S microscope. Micrographs presented in this report were digitally processed to correct for background illumination and contrast only.

RESULTS

The goals of the present study were to determine: 1) whether projections from the VH and adjacent amygdaloid structures to the mPFC and NAC survive lesions of the precommissural fornix; and 2) what pathways do these surviving projections use to reach the mPFC and NAC. Injections into the mPFC were large in order to maximize retrograde labeling in the VH and adjacent structures. Because these projections have all been described previously in detailed published reports, the present report focuses primarily on structures and connections that have been shown to regulate sensorimotor gating in the rat (cf. Swerdlow et al. 2008). Comprehensive reports on other connections pertaining to the present injection targets can be found elsewhere (e.g., mPFC: Hoover and Vertes, 2007; VH: Witter and Amaral, 2004; caudal amygdala: de Olmos et al., 2004).

1. Fluorogold Injections into Medial Prefrontal Cortex

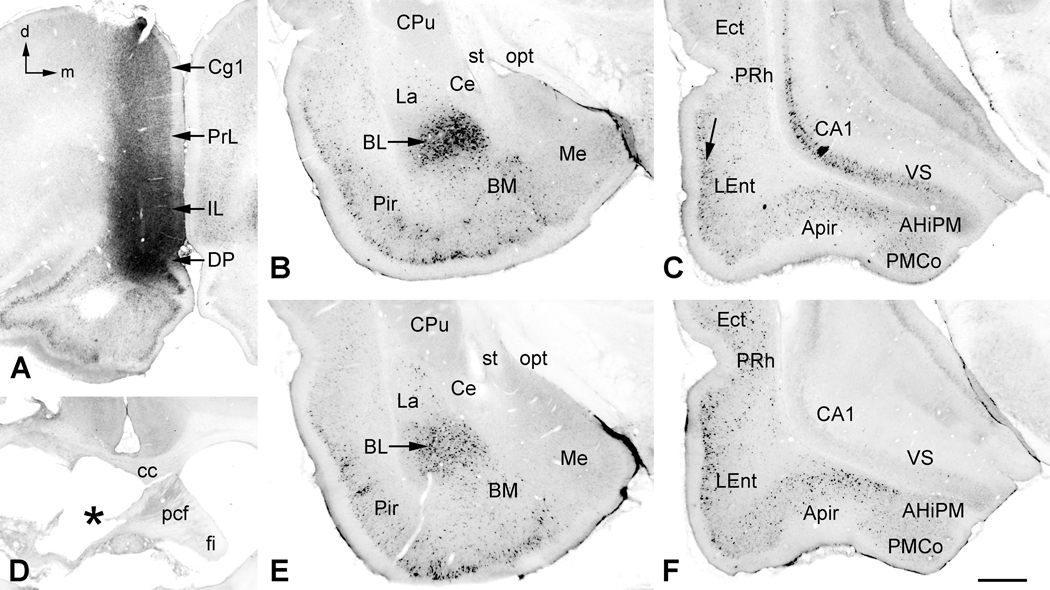

In all 10 of these cases, the core of the injection site was in the infralimbic cortex of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, between bregma A/P levels +3.70 to +3.20 (Paxinos and Watson 1998). From there, the tracer spread dorsally to the prelimbic cortex, ventrally to the dorsal peduncular cortex and, less significantly, rostrally to the medial and ventral orbital cortices (Fig. 1). A halo of retrogradely labeled neuronal cell bodies extended the dorsoventral length of the mPFC, ipsilaterally, and to a lesser extent, contralaterally (Fig. 1A). It is assumed that most of this local retrograde label was due to axonal transport from the injection site, but transport from the injection needle tract likely contributed to some degree.

Figure 1.

Fluorogold injections in medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). A. Core of the injection site in this case was in the dorsal peduncular (DP) and infralimbic (IL) cortices of the mPFC. Retrogradely labeled neurons were found throughout the mPFC on both sides with a heavy ipsilateral concentration in the overlying prelimbic (PrL) and cingulate (Cg1) cortices. B. In the ipsilateral amygdala, large numbers of neurons were retrogradely labeled in the basolateral nucleus (BL), with fewer numbers in the lateral (La) and basomedial (BM) nuclei. Labeling in the medial (Me) and central (Ce) nuclei was sparse to nonexistent, resp. Many neurons in the piriform cortex (Pir) also transported label. C. At the level of the ventral hippocampus, nearly all major structures contained retrogradely labeled neurons, including the CA1 and ventral subiculum (VS), the amygdalopiriform transition area (APir), posteromedial cortical nucleus (PMCo) of the caudal amygdala, and the lateral entorhinal (LEnt), perirhinal (PRh) and ectorhinal (Ect) cortices. In LEnt there was a concentration of labeled neurons along the external granular layer (arrow), with fewer in the deeper layers. D. In a similarly injected case, an electrolytic lesion (asterisk) caused severe damage to the precommissural fornix (pcf) on the side ipsilateral to the fluorogold injection. E. In this case, retrograde labeling in the amygdala and piriform cortex appeared unaffected by the fornix lesion. F. In the ventral hippocampal complex, transport by neurons in the CA1 and VS regions was severely disrupted by the lesion, whereas retrograde labeling in the remaining structures appeared unaffected. Additional abbreviations: AHiPM, posteromedial part of the amygdalohippocampal area; cc, corpus callosum; CPu, caudate/putamen; fi, fimbria; opt, optic tract; st, stria terminalis. Orientation arrows: d, dorsal (for A–F); m, medial (for A–C, E and F). Scale Bar: 0.72 mm (for A), 0.78 mm (for D), 0.5 mm (for B, C, E and F).

In the VH (Fig. 1C), there was extensive retrograde labeling of pyramidal neurons in the CA1 and subicular regions and, to a lesser extent, in neighboring regions, including the LEnt, perirhinal and ectorhinal cortices. In the LEnt, labeled neurons formed a dense band in the superficial cellular layers, with decreased labeling in deeper layers. Structures of the caudal olfactory and vomeronasal amygdala, which lie ventral to the hippocampal formation and ventromedial to the LEnt at this level, also contained labeled neurons. These areas included the amygdalopiriform transition area (APir) and, to a lesser extent, the posteromedial cortical amygdaloid nucleus (PMCo). These structures are mentioned because each lies within range of VH drug infusions used in our behavioral studies, and thus any or all could contribute to the observed suppression of PPI by NMDA infusions into this region of the temporal lobe. Very sparse contralateral labeling was found in the perirhinal and ectorhinal cortices and occasionally in the ventromedial-most part of the PMCo. Five of the cases with mPFC fluorogold injections also had lesions of the precommissural fornix, ipsilateral to the mPFC tracer injection (Fig. 1D). In these cases retrograde labeling in the hippocampal formation (CA1 and VS) all but disappeared (Fig. 1F). Projections from other regions of the VH and caudal amygdala appeared to remain intact, including the meager contralateral projections.

Other structures that have been implicated in the regulation of PPI also contained significant numbers of retrogradely labeled neurons. These included: the dorsal and ventral pallidum (presumed cholinergic projections (e.g., Mesulam et al., 1983; Rye et al., 1984)), medial dorsal thalamic nucleus, ventral tegmental area, and amygdala. The most densely labeled amygdaloid structure was the basolateral nucleus (Fig. 1B). Other structures with labeled neurons, in decreasing order of labeling, were the basomedial, lateral, and medial amygdaloid nuclei. The central nucleus did not label in these cases. Only the basolateral amygdaloid nuclear complex showed light contralateral labeling. As expected, all of these amygdaloid projections survived the fornix lesions (e.g., Fig. 1E).

2. Biotinlylated Dextran Amine Injections into the Ventral Hippocampus Region

Injection placements in the VH ranged from A/P Bregma levels −6.00 to −6.30 (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). Qualitative analysis is focused on structures involved in the regulation of PPI, including the amygdala, NAC, and mPFC. Witter and Amaral (2004) provide a detailed report of intra/extra-hippocampal connectivity in the rat.

Behavioral Confirmation of VH Infusion Sites

Separate behavioral studies (n=16) confirmed previous findings (Swerdlow et al., 2001b) that bilateral NMDA infusions (0.8 µg/0.5 µl) at either of the target coordinates used for the BDA infusions (i.e., VS vs. LEnt) had significant PPI-disruptive effects (VS: p < 0.0001; LEnt: p < 0.001) with no significant effect of infusion site or dose×site interaction (data available at http://psychiatry.ucsd.edu/swerdlow/index.html).

Ventral Subiculum BDA Injections

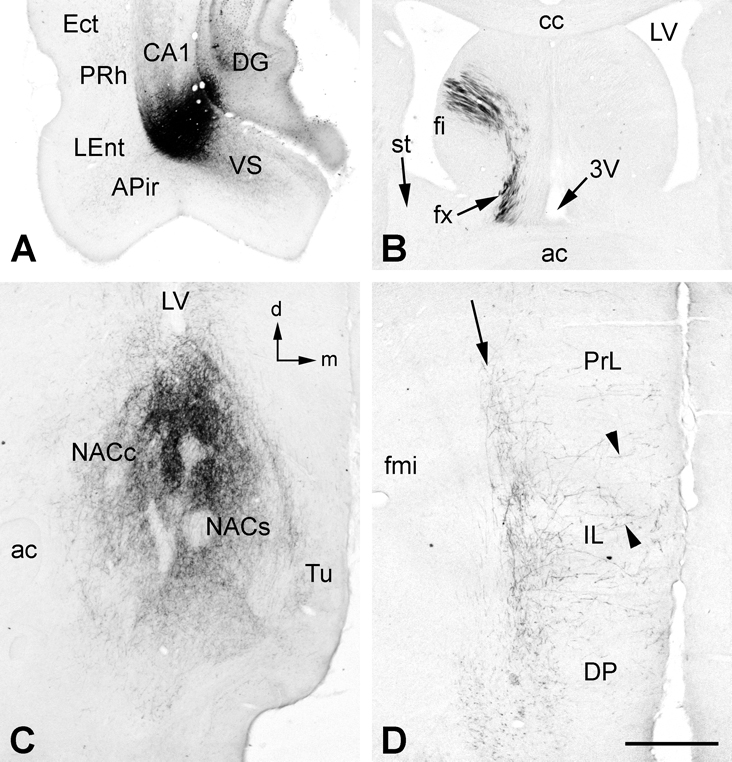

In 4 cases, BDA uptake by somata around the injection site was confined to the VS and the laterally adjacent CA1 (Fig. 2A). In agreement with previous studies (e.g., Canteras and Swanson, 1992; Witter and Amaral, 2004), labeled fibers exiting the hippocampus emerged dorsally within the alveus and proceeded rostrally within the lateral fimbria, or emerged rostrally and proceeded as a ventral projection toward the main body of the amygdala. Of those exiting via the alveus/fimbria, few if any BDA-labeled fibers crossed within the commissure (Fig. 2B), and instead continued ipsilaterally via the septum to innervate the medial shell and the medial part of the NAC core (Fig. 2C), and deep layers of the mPFC (Fig. 2D), including the dorsal peduncular, prelimbic, infralimbic, medial orbitral, and ventral orbital cortices, though less distinctly in the latter two cortices. Fibers exiting rostrally from the injection site proceeded within the posteromedial (AHiPM) and then anterolateral (AHiAL) parts of the amygdalohippocampal area, and in some cases the PMCo, to innervate the posterior and anterior parts of the basal nuclear complex of the amygdala. Rarely did these ventrally situated fibers extend beyond the amygdala after injections confined to the VS/CA1.

Figure 2.

A. An injection of BDA labeled neuronal cell bodies primarily at the CA1/ventral subiculum (VS) border with slight involvement of the overlying dentate gyrus (DG). Locally, BDA-labeled fibers were found in the VS, lateral entorhinal (LEnt), perirhinal (PRh) and ectorhinal (Ect) cortices and the amygdalopiriform transition area (APir), as well in other areas (see text for details). B. Downstream, BDA-labeled fibers passed from the fimbria (fi) to the postcommissural fornix and into the descending column of the fornix (fx). No BDA-labeled fibers were found in the stria terminalis (st) in this case. C. BDA-labeled fibers heavily innervated the medial parts of nucleus accumbens core (NACc) and shell (NACs), with scant innervation of the medial tubercle (Tu). D. In medial prefrontal cortex, BDA-labeled fibers formed a band (arrow) in deep layers of dorsal peduncular (DP), infralimbic (IL) and prelimbic (PrL) cortices, with scattered fibers projecting orthogonally toward more superficial layers (arrowheads). Additional abbreviations: 3V, third ventricle; fmi, forceps minor of corpus callosum. Orientation arrows: d, dorsal (for A, B, C, D); m, medial (for A, C, D). Scale bar = 1 mm (for A and B), 0.5 mm (for C and D).

In 2 additional cases, in which there was a complete or nearly complete lesion of the precommissural fornix in combination with BDA injections confined to the VS and CA1, little if any fiber labeling could be found in the postcommissural column of the fornix and no labeling was observed in either the NAC or mPFC. Fiber labeling normally found in the hypothalamus, thalamus, and mammillary nuclei after VS/CA1 injections of BDA was also absent. In these 2 cases, the only fiber labeling that appeared to survive the lesions was intrahippocampal and in the precommissural fimbria and ipsilateral amygdala.

An additional 2 cases were injected dorsal to the VS, in the overlying dentate gyrus and CA3, to account for any confounding label due to transport from these areas, which lay along the injector tract in the cases described above. Fibers labeled in these 2 cases were seen in CA1 and CA2 ipsilaterally and the dentate gyrus/CA3 bilaterally. Labeled fibers traveled medially in the fimbria and decussated in the commissure of the fornix. The only other innervation was a weak projection to the septal nuclei. Only three of the cases described in the previous and subsequent paragraphs exhibited these additional projections, though weakly labeled, and all had an intact fimbria/fornix.

Lateral Entorhinal Cortex BDA Injections

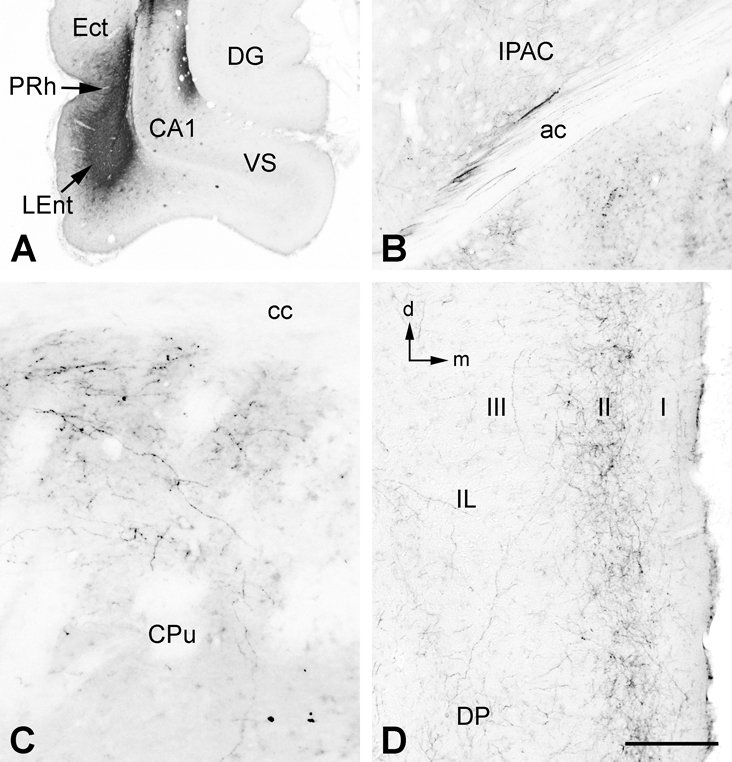

Four cases will be discussed in this section. One case had a unilateral BDA injection that was entirely confined to the lateral part of the LEnt (Fig. 3A). The others had BDA injections in the ventral part of the LEnt including the overlying VS/CA1, and two of these cases had bilateral BDA injections, each with a unilateral lesion of the precommissural fornix. In the first case, the injection site was more lateral than all others and targeted a region that has been referred to as the dorsal intermediate entorhinal field (Insausti et a., 1997) or the dorsolateral entorhinal area (McDonald and Mascagni, 1997). This case was the only one that did not involve some portion of the VS or CA1 and consequently it was the only case that exhibited no labeled fibers in the fimbria or fornix. This case also had a lesion of the precommissural fornix which would have eliminated any fornical projections had any been labeled.

Figure 3.

A. An injection of BDA confined primarily to the dorsal and lateral parts of the lateral entorhinal cortex (LEnt), with some involvement of the perirhinal (PHr) and ectorhinal (Ect) cortices. B. Rostral to the amygdala, some fibers of the ventral amygdalofugal pathway were found entering the posterior limb of the anterior commissure (ac) and innervating its interstitial nucleus (IPAC). C. In this case, BDA-labeled fibers were also found in the dorsal and dorsomedial parts of the rostral caudate/putamen (CPu), immediately adjacent to the external capsule and corpus callosum (cc). D. In medial prefrontal cortex, BDA-labeled fibers formed a band in the superficial cellular layer (II), with sparser label in the molecular layer (I) and deeper layers (e.g., III). Additional abbreviations: DG, dentate gyrus; DP, dorsal peduncular cortex; IL infralimbic cortex. Orientation arrows: d, dorsal; m, medial. Scale bar = 1 mm (for A), 0.2 mm (for B and D), 0.1 mm (for C).

Labeled efferent projections in this case were very similar to cases described by Swanson and Köhler (1986) and Insausti et al. (1997). Fibers within the lateral part of the temporal lobe proceeded rostrally from the injection site through the piriform cortex where they gradually diminished. More ventromedial fibers projected through the lateral and basal nuclear complexes of the amygdala, and then separated into 3 groups. One group of labeled fibers entered the posterior limb of the anterior commissure (AC) and its interstitial nucleus (IPAC – Fig. 3B). Fibers in the IPAC continued on through the bed nuclei of the stria terminalis (BST) and emerged rostrally to produce a significant innervation of the medial shell and medial part of the core of the NAC. At the level of the NAC this group of fibers appeared to merge with a second group that proceeded rostrally from the amygdala as a ventrally situated cluster (the ventral amygdalofugal pathway) which projected rostrally within medial forebrain bundle of the ventral tubercle. This second group of fibers appeared to be the main source of a dense innervation of the medial tubercle, although at the level of the NAC it was impossible to distinguish which of these two groups of fibers was innervating which structure. A third group of fibers exited the amygdala rostrally and entered the caudate/putamen (CPu) and projected forward along the dorsal and dorsomedial rim of the CPu, internal to the external capsule and corpus callosum (Fig. 3C). These fibers appeared to be the source of a dense innervation of the superficial-most cellular layer of the mPFC (Fig. 3D), although fibers continuing from the NAC may also have contributed to this innervation. The band of fibers extended though all regions of the mPFC and the cingulate cortex. A similar, but much less dense, band was present in the contralateral mPFC, and at least one source of this innervation appears to be fibers that entered the posterior limb of the AC (Fig. 3B). These fibers crossed within the decussation of the AC and some were seen to pass from the contralateral posterior limb of the AC into the contralateral external capsule and proceed dorsally toward the contralateral mPFC.

Three other cases had LEnt injections, and in these cases the injection sites were more medial and ventral, in a region that has been referred to as the ventral intermediate entorhinal field (Insausti et a., 1997) or the ventrolateral entorhinal area (McDonald and Mascagni, 1997). All five BDA injections (2 cases had bilateral injections) also significantly labeled the overlying VS/CA1. However, since the two bilateral cases each had a unilateral lesion of the precommissural fornix, we were able to compare projections from the two sides after having eliminated the postcommissural VS/CA1 projection to the NAC and mPFC on one side. Projections were similar to those described above with one significant exception. No BDA-labeled fibers in these cases, or any of the other cases examined in this study, were observed to enter the CPu from the emerging ventral amygdalofugal pathway and proceed toward the mPFC. That particular projection appears to be unique to the more dorsal and lateral region of the LEnt. There was a strong projection to the basal nuclear complex of the amygdala in these cases, most likely due to the projections from the VS/CA1 (described above). Similarities with the previously described case included projections via the IPAC and ventral amygdalofugal pathway that terminated in the medial shell and medial part of the core of the NAC and the medial tubercle. On the lesioned side, however, labeling in the NAC was considerably reduced, reflecting the lost contribution of the VS/CA1 projection. In the mPFC, labeled fibers terminated throughout most layers of the IL but fibers separated into two distinct bands in the PrL, one deep and the other superficial. On the lesioned side, labeled fibers were much diminished, especially in the deep layers of the PrL, again reflecting the lost contribution of the VS/CA1 projection (described above).

BDA Injections Involving the Caudal Amygdala

In 5 cases, the BDA injections penetrated the VS and were taken up also by somata in deeper structures – AHiPM (5 of 5 cases) and PMCo (2 of 5 cases). These latter structures are the caudal part of the vomeronasal amygdala and have clearly defined projections within the amygdala and extended amygdala (e.g., Canteras et al., 1992; de Olmos et al., 2004; Ubeda-Bañon et al., 2008). In these cases, fibers were more prominent in the AHiPM, AHiAL, and PMCo proceeding rostrally, and there was labeling of fibers that entered the stria terminalis. Other fibers continued in the ventral amygdalofugal pathway to innervate the medial tubercle. Some of these appeared to converge in the BST with fibers emerging from the stria terminalis and postcommissural fornix. No noticeable differences were observed in the labeled projections to the NAC and mPFC when compared to those from injections confined to the VS (described above).

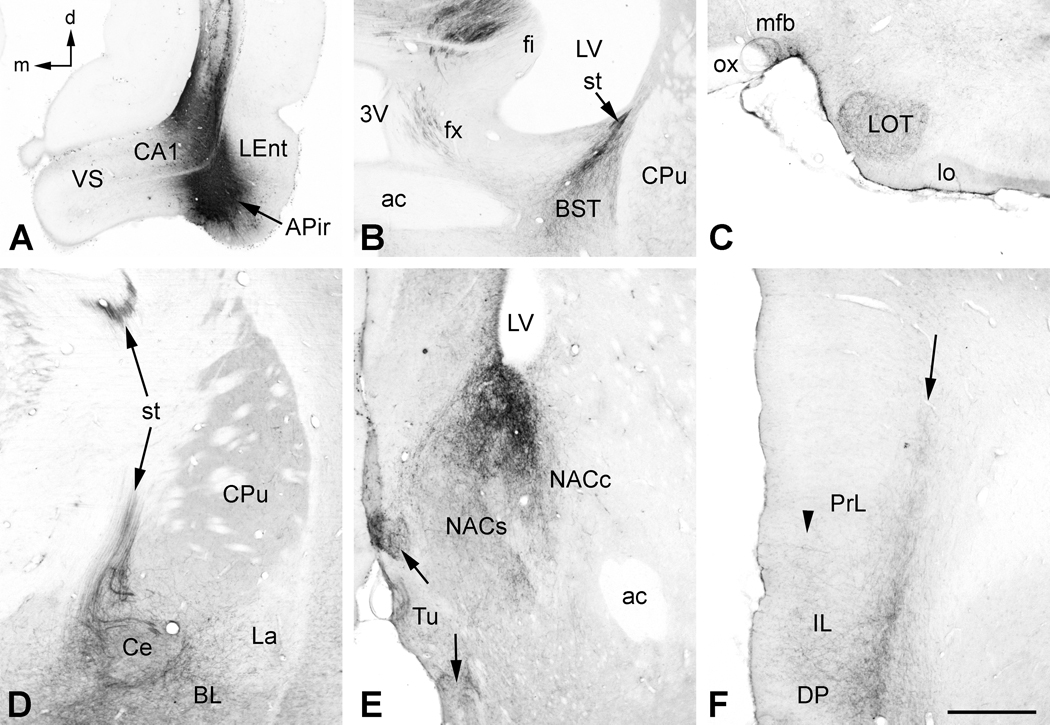

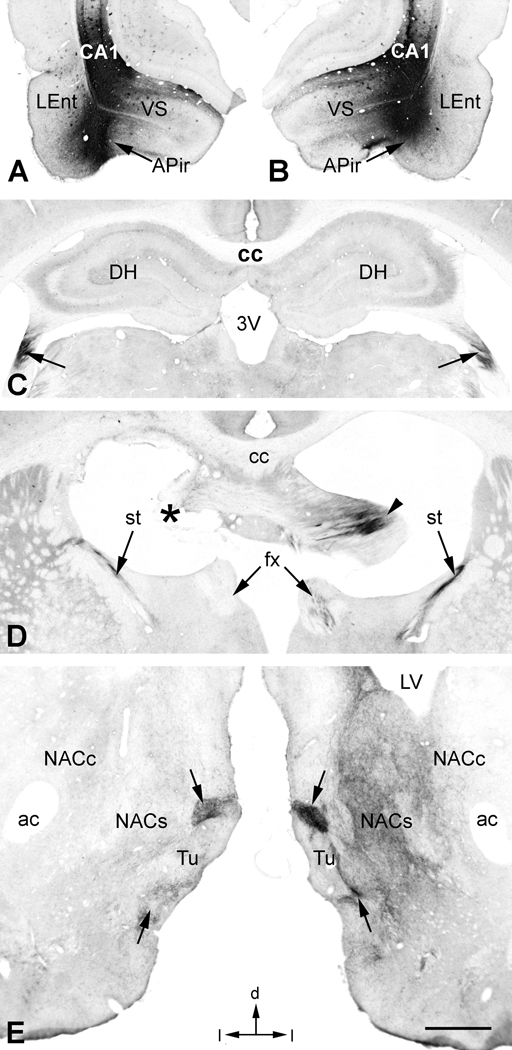

In 3 cases, somatic uptake of BDA was largely confined to the ventrolateral LEnt and adjacent APir, as well as the overlying CA1 region (Fig. 4A). The APir is the caudal most part of the olfactory amygdala and has extensive connections within the amygdala, extended amygdala, and hippocampus (e.g., de Olmos et al., 2004). Much of the labeling in these cases resembled that described above for the ventrolateral LEnt. One major difference was that tightly packed clusters of labeled fibers could be seen passing around and through the central nucleus of the amygdala and entering the stria terminalis (Fig. 4D). These fibers projected to the BST where they merged with fibers exiting the descending column of the fornix (Fig. 4B). Fibers projecting within the ventral amygdalofugal pathway gave rise to a prominent labeling of the nucleus of the lateral olfactory tract (Fig. 4C). Labeling in the NAC (Fig. 4E) and mPFC (Fig. 4F) resembled that seen in other cases with combined LEnt/CA1 injections. The major difference was the prominent labeling of fiber bundles in the medial forebrain bundle entering the medial tubercle (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

A. In this case, the BDA injection was centered in the lateral entorhinal cortex (LEnt) and amygdalopiriform transition area (APir), and also included the ventral CA1. B. In addition to labeling in the precommissural and descending column of the fornix (fx) seen in the previous example, BDA-labeled fibers were also found in the stria terminalis (st) ipsilateral to the injection (compare with Fig 2B). Labeled fibers in the st appeared to mingle with those from the fx to innervate the bed nuclei of the st (BST). C. Additional BDA-labeled fibers projected anteriorly in the ventral part of the medial forebrain bundle (mfb) and a dense plexus of fibers innervated the nucleus of the lateral olfactory tract (LOT). D. BDA-labeled fibers in the st arose from multiple small bundles of fibers that enveloped and innervated the central nucleus of the amygdala (Ce). The basolateral (BLA) and ventral part of the lateral (La) nuclei of the amygdala also contained labeled fibers and terminals. E. In addition to the core (NACc) and shell (NACs) of the nucleus accumbens, there was a strong innervation of the medial tubercle (Tu) in this and similar cases with injections of LEnt/APir. Dense pockets of labeled fibers and terminals in the Tu appeared to be elaborations of fibers of the mfb (arrows). F. Also in this case, there was a more dense innervation of the superficial layers in medial prefrontal cortex (arrowhead), especially in DP and IL, in addition to the deep band of labeling (arrow) compared with Fig. 2D. Additional abbreviations: lo, lateral olfactory tract; ox, optic chiasm. Orientation arrows: d, dorsal; m, medial (for A–F). Scale bar = 1 mm (for A–C), 0.5 mm (for D–F).

After fornix lesions in 8 cases that involved multiple regions, including structures of the caudal amygdala, projections to the NAC and mPFC were severely diminished and sometimes absent altogether. Labeling in other structures, e.g., LOT, IPAC, BST, and the medial tubercle, survived the fornix lesions, presumably due to their separate innervations via the stria terminalis, IPAC and ventral amygdalofugal pathway. This is illustrated in a case that received matched bilateral injections of BDA in the LEnt/APir region (Fig. 5A and B) and a unilateral lesion of the fornix. BDA-labeled fibers could be clearly traced within the fimbria on both sides (Fig. 5C) up to the precommissure (Fig. 5D). At this point, precommissural fibers were evident only on the unlesioned side, some of which continued into the descending column of the postcommissural fornix on that side. BDA-labeled fibers in the stria terminalis bilaterally were unaffected by the lesion. At the level of the NAC (Fig. 5E), fiber labeling in the core and shell was severely depleted on the lesioned side relative to the unlesioned side, whereas labeling in the medial tubercle remained strong on both sides.

Figure 5.

A and B. Matching infusions of BDA in the ventral hippocampus on both sides in this case included the CA1/ventral subiculum (VS) boundary and amygdalopiriform transition area (APir) adjacent to the lateral entorhinal cortex (LEnt). C. BDA-labeled fibers were clearly seen projecting rostrally within the fimbria on both sides (arrows). D. Just upstream of the commissure of the fornix, BDA-labeled fibers were clearly visible on the right side (arrowhead), but were largely obliterated by the electrolytic lesion on the left side (asterisk). Beyond the level of the lesion, postcommissural fibers survived in the descending column of the fornix (fx) only on the right side, although BDA-labeled fibers advancing via the stria terminalis (st) survived on both sides. E. At the level of the nucleus accumbens, BDA-labeled fibers and terminals proliferated in the core (NACc) and shell (NACs) of the nucleus accumbens on the right side, but were severely depleted on the left side by the lesion. Within the medial tubercle (Tu) region, however, dense clusters of BDA labeled fibers and terminals survived on both sides (arrows). Additional abbreviations: DH, dorsal hippocampus. Orientation arrows: d, dorsal; l, lateral (for A–E). Scale bar: 1 mm (for A and B), 0.93 mm (for C), 0.8 mm (for D), 0.5 mm (for E).

To identify transport that may have been due to tracer uptake along the injection needle track, 3 additional cases received injections superficial to the LEnt/APir. These were targeted in the CA1/CA2 area of the ventral hippocampus, immediately above the LEnt/APir and just dorsolateral to the VS injections described above. Labeling patterns were similar to the aforementioned VS injections. These cases were notable because they were the only ones in which significant somatic uptake was found outside of the injected hippocampus or occasionally in the diagonal band nuclei. In two of these cases, there was significant retrograde somatic labeling in the CA3 region of the contralateral hippocampus. In one case, labeled fibers could clearly be seen decussating within the commissure of the fornix. Similar but weak labeling in the contralateral CA3 was found in only one case in which the LEnt/APir was the primary target.

Finally, the absence of somatic (retrograde transport) BDA-labeling in the laterobasal nuclear complex (BLA) of the amygdala was a prerequisite for including cases in these analyses, because this additional labeling is a potentially confounding factor when interpreting projections to regions innervated by both the VH and the BLA, e.g., the mPFC and NAC (e.g., Krettek and Price, 1977; Jay and Witter, 1991; Conde et al., 1995, and present study). Only one case was excluded by this criterion; that case had bilateral BDA injections in the VH together with a unilateral fornix lesion. That case and several others were produced primarily for illustrative purposes, i.e., to compare BDA transport between sides with and without a fornix lesion in the same animal (e.g., Fig. 5). Projections from these bilaterally injected cases were indistinguishable from those with unilateral injections when one considered projections ipsilateral to the injection site, and whether or not the projections were ipsilateral or contralateral to the fornix lesion.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies by our group reported that the PPI-disruptive effects of intra-VH NMDA persisted after bilateral lesions of the fornix, but were opposed by lesions of the mPFC (Swerdlow et al., 2004; Shoemaker et al. 2005). One implication of these studies was that the PPI-disruptive effects of intra-NMDA infusion appeared to be mediated via VH projections to the mPFC that did not involve the fornix. The VH, as used in this report, includes the ventral structures of the hippocampal formation (dentate gyrus, hippocampus (CA1, CA2, CA3), and subiculum) as well as those of the parahippocampal region (entorhinal, perirhinal, and postrhinal cortices, presubiculum, and parasubiculum), after Witter and Amaral (2004). Essentially, it includes all non-amygdaloid structures ventral to the rhinal fissure at this A/P level. Our present findings confirm that the CA1/subiculum projections of the hippocampal formation reach the mPFC and NAC via a fornical route. However, additional connections from neighboring structures of the VH and amygdala reach their targets in the ventral forebrain via several additional routes, including the stria terminalis (caudal amygdala), ventral amygdalofugal pathway (LEnt and caudal amygdala), and the IPAC (LEnt). Moreover, there is a large projection from the dorsolateral part of the LEnt that projects to mPFC along the dorsal and dorsal medial rim of the CPu (see also Swanson and Köhler, 1986; Isausti et al., 1997).

The goal of this study was not to compile a comprehensive description of the fibers connecting the ventral temporal lobe with the forebrain. Rather, it was to clearly identify the pathways used by non-fornical projections from caudal parts of the ventral temporal lobe in the rat that might mediate the PPI-disruptive effects of intra-VH NMDA infusion. Findings from an abundance of retrograde studies (e.g., Witter and Amarl, 2004; de Olmos et al. 2004) were uninformative in this regard, since the actual pathways are not labeled in such studies. Our own retrograde findings confirmed these previous reports, and allowed us to clearly identify which structures adjacent to the hippocampal formation might contribute to the behavioral effects observed by our group (e.g., Wan et al. 1996) and others (e.g. Zhang et al. 1999; Bast et al. 2001) when NMDA is injected into this part of the rat brain. Injections were large to maximize retrograde labeling in the temporal lobe, though were still only 40% of the volume of infusions typically used in studies of the PPI-disruptive effects of intra-VH NMDA infusion. While the injection techniques surely damaged fibers of passage, we were less concerned with potential issues of damaged axons, since these connections have been well described in detailed studies.

Findings from our anterograde tracing studies are generally consistent with other studies that examined efferent projections of the LEnt and caudal amygdala, but detailed anterograde studies of the region of the ventral temporal lobe injected in our behavioral studies are few and generally confined to efferent targets unrelated to the behaviors that we study. For example, two studies have examined the efferent projections of the APir with the anterograde tracer, PHA-L, but only as they relate to intra-amygdaloid connections (McDonald et al., 1999; Jolkkonen et al., 2001). Another study (Shammah-Lagnado and Santiago, 1999) describes a projection to the infralimbic cortex of the mPFC from a case in which the middle third of the APir was injected with PHA-L, but that case was injected well rostral to the A/P level that we use in our behavioral experiments. An anterograde tracer study of projections from PMCo using fluorescent dextran amines (Ubeda-Bañon et al., 2008) reported fibers terminating in the olfactory tubercle and islands of Calleja with sparse labeling in the medial accumbens shell. Fibers were not followed beyond this level. A detailed anterograde tracing study with PHA-L by Canteras et al., (1992) examined the projections of the AHi transition area and the PMCo and found projections via the stria terminalis and, to a lesser extent, the ventral amygdalofugal pathway that terminated in the medial parts of the accumbens and in the infralimbic region of mPFC. But, again, these injections were 2+ mm rostral to the level that we use in our behavioral studies. Beyond the present report, we know of no clear description of the pathways taken by projections from the caudal amygdala at the A/P level of the temporal lobe from which we gather our behavioral data. It should be noted, however, that the reduced PPI after infusion of NMDA into the ventral temporal lobe is not likely to reflect a significant contribution of amygdaloid structures, since PPI is reduced after blockade (rather than stimulation) of NMDA receptors in the basolateral amygdala (Wan and Swerdlow 1997).

Regarding the LEnt, two well illustrated studies by Swanson and Köhler (1986) and Insausti et al. (1997) with PHA-L as an anterograde tracer described a projection from LENT to prefrontal cortex. Both studies indicated fibers proceeding rostrally either within or adjacent to the corpus callosum. We observed fibers projecting along the rim of the CPu just beneath the corpus callosum in only one case, and that injection was the only one in which the dorsolateral part of the LEnt was included in the injection site. Drug infusion sites used in our behavioral experiments are typically more ventral than this and may not involve this pathway; yet, the extent of drug diffusion that takes place in those behavioral studies is unclear. Our studies indicate that the ventromedial part of the LEnt does not project to mPFC via that more dorsal route, but rather by way of the IPAC and/or ventral amygdalofugal pathway. Finally, a study by Totterdell and Meredith (1997) with biocytin and BDA as tracers reports that a few fibers pass into the stria terminalis to reach the accumbens from the LEnt. We have also observed this, but found that fibers in the stria terminalis were most heavily labeled when the caudal amygdala, particularly the APir, was included in the injection site.

While the 10 kDa BDA is taken up and transported primarily in the anterograde direction, it can produce some retrograde labeling as well (Veenman et al., 1992). In our material we found only one case with retrogradely labeled neurons beyond those labeled near the injection site and the few occasionally found in the diagonal band nuclei. As mentioned above, that case was excluded from the study. This is significant, for it has been demonstrated that 10 kD BDA can be transported anterogradely in collaterals of axons that are initially labeled retrogradely. Such collateral transport from retrogradely labeled neurons can give rise to “false anterograde transport”. While direct collateral to collateral transfer of the BDA has been suggested as one possible mechanism (Chen and Aston-Jones, 1998), given the survival times used in the present study, it is unlikely that the neuronal cell body in such cases would not also be retrogradely labeled. In any event, the amount of retrograde transport (and, consequently, “false anterograde transport”) is expected to be minor in the present study compared to the amount of true anterograde transport from our injection sites. Another issue is false transport by neurons with cut axons passing through in the injection site. Our injections were deliberately large to maximize pathway labeling and mimic infusion parameters in behavioral studies and, undoubtedly, this caused considerable mechanical damage. This is typically a confound when interpreting retrograde transport of a tracer, since the transected axon is capable of taking up tracer and transporting it back to the cell body (e.g., Novikov, 2001). In the case of our BDA injections in the ventral temporal lobe, retrograde labeling, possibly resulting from damaged axons, was typically seen caudal to but in the same region of the temporal lobe as the injection site. Consequently, we would not expect any “false anterograde transport” by these neurons to significantly confound our interpretation of the results. Retrograde transport by cut axons could also account for the occasional labeling of neurons that we observed in the diagonal band (presumed source of cholinergic innervation – c.f. Shute and Lewis, 1967), which were seen in cases with an intact fornix.

Although we have shown that the mPFC (and NAC) are innervated from the ventral temporal lobe by projections that do not pass through the fornix, this non-fornical innervation is considerably weaker than that provided by the hippocampal formation. It could be argued that the labeling that survives fornix lesions is due to incomplete lesions of the fornix. Yet our retrograde studies after fluorogold injections in mPFC indicate that even when transport by neurons in the VS and CA1 is completely eliminated by fornix lesions, there is still robust retrograde labeling in the LEnt and caudal amygdala.

The present findings suggest a mechanism whereby the VH might access PPI-regulatory circuitry in the ventral forebrain – particularly the NAC and mPFC – via non-fornical routes. At present, there is direct evidence for a role of the mPFC in mediating the PPI-disruptive effects of intra-VH NMDA infusion, while a similar role for the NAC is based only on indirect evidence, e.g. NAC c-Fos activation by intra-VH NMDA infusion (Klarner et al. 1998). It remains to be determined which structures and pathways are ultimately responsible for the PPI-disruptive effects of intra-VH NMDA infusion after fornix lesions. Studies in progress will assess the role of the identified non-fornical forebrain projections in regulating these effects.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by MH53484. The authors acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Ms. Niveditha Thangaraj.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- AC

anterior commissure

- AHiAL

amygdalohippocampal area, anterolateral part

- AHiPM

amygdalohippocampal area, posteromedial part

- APir

amygdalopiriform transition area

- BDA

biotinylated dextran amine

- BLA

basolateral amygdaloid nucleus

- BST

bed nuclei of the stria terminalis

- CPu

caudate/putamen of the striatum

- IPAC

interstitial nucleus of the posterior limb of the anterior commissure

- LEnt

lateral entorhinal cortex

- LOT

nucleus of the lateral olfactory tract

- mPFC

medial prefrontal cortex

- NAC

nucleus accumbens

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartate

- PMCo

posteromedial cortical amygdaloid nucleus

- PPI

prepulse inhibition

- TBS

tris-buffered saline

- VH

ventral hippocampal region

- VS

ventral subiculum

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure

In the past 3 years, NRS has had grant support from Allergan, Inc., and was a paid Consultant to Sanofi/Aventis.

REFERENCES

- Bast T, Zhang WN, Heidbreder C, Feldon J. Hyperactivity and disruption of prepulse inhibition induced by N-methyl-D-aspartate stimulation of the ventral hippocampus and the effects of pretreatment with haloperidol and clozapine. Neuroscience. 2001;103:325–335. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff D, Stone C, Callaway E, Geyer M, Glick I, Bali L. Pre-stimulus effects on human startle reflex in normals and schizophrenics. Psychophysiology. 1978;15:339–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1978.tb01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canteras NS, Swanson LW. Projections of the ventral subiculum to the amygdala, septum, and hypothalamus: a PHA-L anterograde tract-tracing study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1992;324:180–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.903240204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canteras NS, Simerly RB, Swanson LW. Connections of the posterior nucleus of the amygdala. J Comp Neurol. 1992;324:143–179. doi: 10.1002/cne.903240203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Aston-Jones G. Axonal collateral-collateral transport of tract tracers in brain neurons: false anterograde labelling and useful tool. Neuroscience. 1998;82:1151–1163. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00336-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde F, Maire-Lepoivre E, Audinat E, Crepel F. Afferent connections of the medial frontal cortex of the rat: cortical and subcortical afferents. J Comp Neurol. 1995;352:567–593. doi: 10.1002/cne.903520407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Olmos JS, Beltramino CA, Alheid G. Amygdala and extended amygdala of the rat: A cytoarchitectonical, fibroarchitectonical, and chemoarchitectonical survey. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. 3rd Edition. Academic Press; 2004. pp. 509–603. [Google Scholar]

- Graham F. The more or less startling effects of weak prestimuli. Psychophysiology. 1975;12:238–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1975.tb01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover WB, Vertes RP. Anatomical analysis of afferent projections to the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat. Brain Struct Funct. 2007;212:149–179. doi: 10.1007/s00429-007-0150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insausti R, Herrero MT, Witter MP. Entorhinal cortex of the rat: Cytoarchitectonic subdivisions and the origin and distribution of cortical efferents. Hippocampus. 1997;7:146–183. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1997)7:2<146::AID-HIPO4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay TM, Witter MP. Distribution of hippocampal CA1 and subicular efferents in the prefrontal cortex of the rat studied by means of anterograde transport of Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin. J Comp Neurol. 1991;313:574–586. doi: 10.1002/cne.903130404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolkkonen E, Miettinen R, Pitkanen A. Projections from the amygdalo-piriform transition area to the amygdaloid complex: a PHA-L study in rat. J Comp Neurol. 2001;432:440–465. doi: 10.1002/cne.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klarner A, Koch M, Schnitzler HU. Induction of Fos-protein in the forebrain and disruption of sensorimotor gating following N-methyl-D-aspartate infusion into the ventral hippocampus of the rat. Neuroscience. 1998;84:443–452. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krettek JE, Price JL. Projections from the amygdaloid complex to the cerebral cortex and thalamus in the rat and cat. J Comp Neurol. 1977;172:687–722. doi: 10.1002/cne.901720408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Mascagni F. Projections of the lateral entorhinal cortex to the amygdala: A Phaseolus vulgaris Leucoagglutinin study in the rat. Neuroscience. 1997;77:445–459. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Shammah-Lagnado SJ, Shi C, Davis M. Cortical Afferents to the extended amygdala. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;877:309–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M-M, Mufson EJ, wainer BH, Levey AI. Central cholinergic pathways in the rat: An overview based on an alternative nomenclature (Ch1–Ch6) Neuroscience. 1983;10:1185–1201. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogenson GJ, Nielsen M. A study of the contribution of hippocampal-accumbenssubpallidal projections to locomotor activity. Behav Neural Biol. 1984;42:38–51. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(84)90412-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novikov LN. Labeling of central projections of primary afferents in adult rats: A comparison between biotinylated dextran amine, neurobiotin™ and Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin. J Neurosci Meth. 2001;112:145–154. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 4th Edition. San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rye DB, Wainer BH, Mesulam M-M, Mufson EJ, Saper CB. Cortical projections arising from the basal forebrain: A study of cholinergic and noncholinergic components employing retrograde tracing and immunohistochemical localization of choline acetyltransferase. Neuroscience. 1984;13:627–643. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shammah-Lagnado SJ, Santiago AC. Projections of the amygdalopiriform transition area (APir): a PHA-L study in the rat. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;877:655–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker JM, Saint Marie RL, Bongiovanni MJ, Neary AC, Tochen LS, Swerdlow NR. Prefrontal D1 and ventral hippocampal NMDA regulation of startle gating in rats. Neuroscience. 2005;135:385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shute CCD, Lewis PR. The ascending cholinergic reticular system: neocortical, olfactory and subcortical projections. Brain. 1967;90:497–520. doi: 10.1093/brain/90.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Köhler C. Anatomical evidence for direct projections from the entorhinal area to the entire cortical matle in the rat. J Neurosci. 1986;6:3010–3023. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-10-03010.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Geyer MA, Braff DL. Neural circuit regulation of prepulse inhibition of startle in the rat: Current knowledge and future challenges. Psychopharm. 2001a;156:194–215. doi: 10.1007/s002130100799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Hanlon FM, Henning L, Kim YK, Gaudet I, Halim ND. Regulation of sensorimotor gating in rats by hippocampal NMDA: anatomical localization. Brain Res. 2001b;898:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02143-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Shoemaker JM, Noh HR, Ma L, Gaudet I, Munson M, Crain S, Auerbach PP. The ventral hippocampal regulation of prepulse inhibition and its disruption by apomorphine in rats are not mediated via the fornix. Neuroscience. 2004;123:675–685. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Weber M, Qu Y, Light GA, Braff DL. Realistic expectations of prepulse inhibition in translational models for schizophrenia research. Psychopharm. 2008;199:331–388. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1072-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totterdell S, Meredith GE. Topographical organization of projections from the entorhinal cortex to the striatum of the rat. Neuroscience. 1997;78:715–729. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00592-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubeda-Bañon I, Novejarque A, Mohedano-Moriano A, Pro-Sistiaga P, Insausti R, Martinez-Garcia F, Lanuza E, Martinez-Marcos A. Vomeronasal inputs to the rodent ventral striatum. Brain Res Bull. 2008;75:467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenman CL, Reiner A, Honig MG. Biotinylated dextran amine as an anterograde tracer for single- and double-labeling studies. J Neurosci Meth. 1992;41:239–254. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(92)90089-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan FJ, Caine SB, Swerdlow NR. The ventral subiculum modulation of prepulse inhibition is not mediated via dopamine D2 or nucleus accumbens non-NMDA glutamate receptor activity. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;314:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00535-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan FJ, Swerdlow NR. The basolateral amygdala regulates sensorimotor gating of acoustic startle in the rat. Neuroscience. 1997;76:715–724. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witter MP, Amaral DG. Hippocampal formation. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. 3rd Edition. Academic Press; 2004. pp. 635–670. [Google Scholar]

- Yee BK, Feldon J, Rawlins JN. Latent inhibition in rats is abolished by NMDA-induced neuronal loss in the retrohippocampal region, but this lesion effect can be prevented by systemic haloperidol treatment. Behav Neurosci. 1995;109:227–240. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.109.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Pouzet B, Jongen-Rêlo AL, Weiner I, Feldon J. Disruption of prepulse inhibition following N-methyl-D-aspartate infusion into the ventral hippocampus is antagonized by clozapine but not by haloperidol: a possible model for the screening of atypical antipsychotics. Neuroreport. 1999;10:2533–2538. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199908200-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]