Abstract

Using an ‘at-risk’ sample of African American girls, the present study examined the link between girls' retrospective reports of pubertal timing, girls' perceived relative pubertal timing, and their behavioral and emotional problems as rated by the girls themselves (N = 102; 11 to 17 years), as well as teachers and parents. Structural equation modeling results indicated that the girls' retrospective reports of menarche were significantly related to their perceived relative menarche, whereas the girls' retrospective reports of development of their breasts were not related to their perceived relative development of breasts. Girls who perceived their breasts developing early relative to their peers were more likely to engage in delinquent behaviors according to teacher report. Significant effects of teacher reported adolescent internalizing problems also were found for girls who retrospectively reported either early or late development of breasts. The study's findings underscore the importance of teasing apart the effects of different indicators of girls' pubertal development on psychosocial adjustment and including teachers' reports of girls' emotional and behavioral problems, particularly among girls with the additional risks associated with residing in an economically disadvantaged urban setting.

Keywords: perceived pubertal timing, pubertal timing, ‘at-risk’ populations, African American adolescent girls, internalizing-, externalizing-problems, development of breasts, menarche

Research findings consistently show a significant link between pubertal timing and adolescent girls' behavioral and emotional problems. Girls who experience puberty early display more problem behaviors and signs of emotional distress than their peers who experience puberty either on-time or late (e.g., Brooks-Gunn, Paikoff, & Warren, 1994; Caspi & Moffitt, 1991; Ge, Conger, & Elder, 1996, 2001). This link has been established mainly in samples of European American girls (see Buchanan, Eccles, & Becker, 1987; Connolly, Paikoff, & Buchanan, 1996, Ellis, 2004, for reviews). Research using samples of African American girls is sparse. The little work that has been conducted has yielded inconsistent findings (e.g., Ge, Brody, Conger, Simons, & Murray, 2002; Ge, Kim, Brody, Conger, Simons, Gibbons et al., 2003; Michael & Eccles, 2003; Siegel, Yancey, Aneshensel, & Schuler, 1999). Some studies report similar findings as those obtained with European American girls (Ge et al., 2002; Ge et al., 2003; Siegel et al., 1999); other studies (Michael & Eccles, 2003; Striegel-Moore, McMahon, Biro, Schreiber, Crawford, & Voorhees, 2001) have not found a link between early pubertal development and behavioral and emotional problems in African American girls.

Because the physical changes associated with puberty tend to occur earlier in African American girls (Herman-Giddings, Slora, Wasserman, Bourdony, Bhapkar, & Koch et al., 1997), improved understanding about the nature of the link between early pubertal timing and behavioral and emotional problems within this population is needed. A further reason to improve understanding about the link stems from research indicating that the physical changes associated with puberty may hold different meanings for African American girls due to ethnic variations in standards of physical attractiveness (Halpern, Udry, Campbell, & Suchindran, 1999). For example, African American adolescent girls tend to describe their beauty ideals in terms of personality characteristics (e.g., style, attitude, pride, confidence); whereas European American adolescent girls tend to describe their beauty ideal in terms of fixed physical attributes (e.g., tall, thin, high cheekbones) (Parker, Nichter, Vuckovic, Sims, & Ritenbaugh, 1995). The effects of pubertal timing on African American girls' psychosocial adjustment may therefore vary depending on the extent to which African American girls depart from the African American subculture standards of “feminine” physical attractiveness. As such, the main purpose of the present study was to clarify the nature of the link between early pubertal timing and behavioral and emotional problems among adolescent African American girls.

Age of Menarche and Development of Breasts: Distinct Constructs with Distinct Ramifications

Most research on pubertal development and adolescent girls' behavioral and emotional problems has focused on age of menarche (see Hayward, 2003). Although some studies have used multiple indicators of development, such as age of menarche, development of breasts, changes in height, and changes in skin, these indicators have usually been combined into a single index of pubertal development. The present study proposes, however, that different types of physical development may have different effects on girls' behavioral and emotional problems. As a consequence, the study focuses on two aspects of girls' pubertal development: (1) age of menarche and (2) development of breasts (Brooks-Gunn & Warren, 1985; Slap, Khalid, Paikoff, Brooks-Gunn, & Warren, 1994; Swarr & Richards, 1996). Development of breasts is distinct from menarche because the former is a visible event likely to draw public reactions. Menarche, in contrast, is a private event and may not be a factor in girls' social interactions. Given that the development of breasts has a distinctively social impact, it is important to separate the experience of developing breasts from the experience of menarche. The present study thus explored the independent influence of the development of breasts and age of menarche on behavioral and emotional problems in African American adolescent girls.

Beyond Girls Retrospective Reports of Pubertal Timing: Perceived Relative Pubertal Timing and Girls' Psychosocial Adjustment

Distinct from age at menarche is a girl's perception of her pubertal timing relative to her peer group. Perceived relative pubertal timing indexes whether girls see themselves as being nonnormative in one direction (early) or the other (late), which can affect girls images of themselves and in turn, their adjustment. Studies of relative pubertal timing suggest more difficulties among adolescents who perceive themselves to be either early or late in their pubertal development relative to adolescents who perceive themselves to be on-time (e.g., Michael & Eccles, 2003; Siegal et al., 1999). Michael and Eccles (2003) examined the influence of ethnicity/race, perceived relative pubertal timing, retrospective self-reports of pubertal timing (i.e., age of menarche) on adolescent girls' psychosocial adjustment (i.e., depressive symptoms, eating disturbance, anger, problem behaviors, and total internalizing and externalizing behavior problems). Results indicated that both African American and European American girls who perceived their pubertal timing as either early or late relative to their peers had significantly more depressive symptoms, eating disturbance, anger, and problem behaviors than girls who perceived their development as on time. Interestingly, girls' retrospective reports of pubertal timing were not significantly related to depressive symptoms, eating disturbance, anger, and problems behaviors among the African American girls.

Pubertal Timing and Theoretical Frameworks

One explanation for the relation between pubertal timing and behavioral and emotional problems is the Stage Termination Hypothesis (Peskin & Livson, 1972; Petersen & Taylor, 1980). This hypothesis states that early pubertal timing does not allow girls sufficient time to complete prior developmental tasks before the onset of puberty and new developmental pressures (e.g., moving into older mixed-sex peer groups, entering romantic relationships). The physical changes that occur during puberty may compound early developing girls' difficulties because other individuals (e.g., peers, parents, teachers) may view the girls as older and more socially and cognitively advanced than the girls, in fact, are (Caspi, 1995; Caspi & Moffitt, 1991).

An alternative explanation is the Social Deviance Hypothesis (Alsaker, 1992, 1995). This hypothesis states that early and late pubertal timing place adolescents out of sync with the normative experiences of their peers during a developmental period that is already characterized by heightened vulnerabilities. As a result, both early and late developing girls are anticipated to be at greatest risk for adjustment difficulties due, in part, to the perceived lack of shared experience with others. Recall that in Michael and Eccles (2003), both African American and European American girls who perceived their pubertal timing as either early or late relative to their peers had significantly more psychosocial adjustment problems than girls who perceived their development as on time, thus supporting the Social Deviance Hypothesis. Michael and Eccles (2003), however, did not address the development of breasts.

The Nature of Behavioral and Emotional Outcomes: What One Source Sees Another Does Not

Past research in this area has relied almost exclusively on either parent or youth as informants of the youths' psychosocial adjustment (Alsaker, 1996). However, findings from Latinen-Krispijn, Van der Ende, Hazebroek-Kampschreur, and Verhulst (1999) suggest links between pubertal timing and outcomes in adolescents may depend on the informant. Disparate results as a function of the informant source has been well documented in the literature (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987). Adolescent reports can differ from parent reports for many reasons. First, what is memorable to a parent may not be memorable to an adolescent and vice versa. Second, the behavioral universe to which a parent has access to is not the same as the universe of behaviors to which the adolescent has access.

In addition, because girls function in multiple settings, using just youth and/or parents as informants may not adequately capture the domains that are affected by pubertal timing. An important setting for youth is the school, as this is a setting that parents have limited access. We could not locate any study on pubertal timing and social and behavioral adjustment that used teachers as informants of the girls' behavioral and emotional problems despite the apparent advantages in having teachers provide information about girls' functioning in the school setting (Achenbach, 1999). The present study thus used parents, adolescents, and teachers as sources of ratings of girls' psychosocial adjustment, and in doing so, extends past research. Based on the common observation that adolescents are more accurate in reporting their internalizing problems than externalizing problems while parents and teachers are more accurate in reporting youths' externalizing problems than internalizing problems (Achenbach, 1999), we expected internalizing problems such as anxiety and depression would be linked to pubertal timing when rated by the adolescent. Conversely, we expected behavioral problems such as delinquency and aggression would be linked to pubertal timing when rated by the parent and teacher.

A Structural Equation Model: A Multivariate Perspective

In summary, the present study examined how girls' retrospective reports of pubertal timing and perceived relative pubertal timing are linked to behavioral and emotional problems among African American adolescent girls. The study also examined how girls' retrospective reports of the development of their breasts and perceived relative development of breasts are related to behavioral and emotional problems, independent of girls' retrospective reports of age of menarche and perceived age of menarche. These relations were examined for behavioral and emotional problems as rated by adolescents, parents, and teachers, thus adding a new source dimension into the literature. Further, because girls' perceptions of their pubertal timing are subjective and based in part on their own sense of development relative to their peers, it was of interest to examine how girls' perceptions of relative pubertal timing related to the girls' retrospective reports of pubertal timing.

A final innovation of the current research was its focus on a sample of vulnerable African American adolescent girls who reside in an economically disadvantaged urban setting. Such girls are at increased risk of engaging in problem behaviors, including substance use and mental health conditions (e.g., depression; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). Given the challenges that adolescent girls in disadvantaged urban settings face, a better understanding of the effects of pubertal timing on psychosocial adjustment within this population is needed. This study's sample thus focused on a subset of these youth who had been referred to a counseling center for having conflicts in school or home (e.g., truancy, running away).

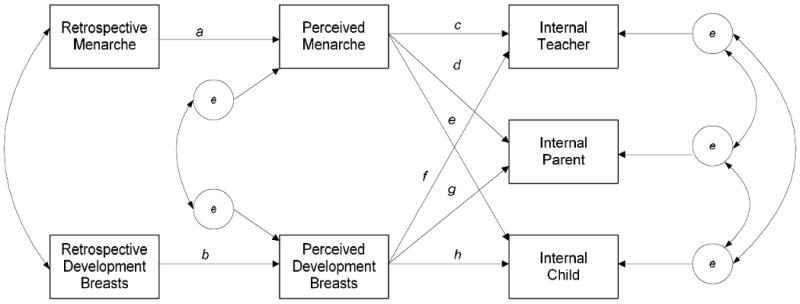

The hypothesized dynamics of the current study are captured in the path diagram in Figure 1. Girls' retrospective reports of menarche are assumed to influence girls' perceived relative menarche (path a) and girls' retrospective reports of development of breasts are assumed to influence girls' perceived relative development of breasts (path b). Perceived relative menarche and perceived relative development of breasts are seen as potentially influencing the outcome variables as characterized by each of the three sources -- parent, teacher, and adolescent (see paths c through h). Although different associations were expected as a function of the behavior and source, Figure 1 represents the most general formulation that includes potential effects on all three source reports.

Figure 1. Theoretical Model.

In addition, Figure 1 assumes that the effects of girls' retrospective reports of menarche on outcomes are mediated completely by girls' perceived relative menarche and that the effects of girls' retrospective reports of the development of breasts are mediated by the girls' perceived relative development of breasts. In point of fact, these mediators may be only partial rather than complete. No study has tested this possibility. The present study will provide perspectives on these mediational dynamics. Figure 1 also includes correlated error where it is reasonable to assume that factors other than the common cause are impacting the correlation between variables. For example, factors other than perceived relative menarche and perceived relative development of breasts can contribute to the correlation between the outcome variables (e.g., hormone action, genetics, and ethnicity). Lastly, Figure 1 illustrates the case of a single outcome variable (e.g., externalizing as reported by the parent, teacher, and adolescent). In the modeling, multiple outcomes were pursued.

Method

Participants

Parents of 102 African American adolescent girls enrolled in an educational and counseling center within a public school that serves an urban population provided informed consent. The girls' ages ranged from 11 to 17 years (M = 14.69 years SD = 1.49), with most in the 8th grade (M = 8.38 grade, SD = 1.39). The primary caregivers' educational level, taken from school records, was predominately some high school or less (69.2%). Fifty-eight percent of the adolescents resided with their biological mother, 7% with a legal guardian, 14%, lived with both parents, and 12% had some other living arrangement (e.g., foster parents).

Measures

Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 (CBCL), Youth Self-Report (YSR) and Teacher Report Form (TRF) (Achenbach, 1991)

The CBCL contains 113 items on which parents rate their child's behavioral and emotional problems. Scoring yields two broadband internalizing and externalizing factors and eight specific narrow-band factors (Aggressive Behavior, Anxious/Depressed, Attention Problems, Delinquency, Social Problems, Somatic Complaints, Thought Problems, and Withdrawn). For this study, T-scores were used from the two broadband Internalizing and externalizing factors and the eight specific narrow-band factors. For reliability and validity data, which is extensive, see Achenbach and Edelbrock (1983). The YSR and TRF each contain items that parallel the CBCL. Both have been used extensively and have excellent reliability and validity empirical bases (Achenbach, 1991, Achenbach, 1999; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983).

Girls' Retrospective Reports of Pubertal Timing and Development of Breasts

Self-reported age of menarche and development of breasts were used as two separate indexes of girls' retrospective reports of pubertal timing. In individual interviews, the adolescent girls were asked to provide their age in years at “the time of [your] first period” and “the time when [you] started developing breasts. Although previous research (e.g., Bisaga et al., 2002) has defined “Early” and “Late” pubertal timing as two standard deviations below or above the relative distribution of age at menarche within the total sample, this study's analyses used age of menarche as a continuous construct rather than imposing artificial cutoff values that undermine the continuous nature of the construct. Other studies have suggested that adolescent girls tend to be accurate in reporting their menstrual age (Brooks-Gunn, Warren, Rosso, & Gargiulo, 1987; Caspi & Moffitt, 1991; Dubas, Graber, & Petersen, 1991; Graber, Brooks-Gunn, & Warren, 1995, Graber, Lewinsohn, Seeley, Brooks-Gunn, 1997). In this study, the mean age of menarche within the sample was 11.91 years (SD = 1.21).

For development of breasts, the black and white drawings (Tanner, 1972) and written descriptions of the lateral breasts development for Tanner Stages Category 2 were used as a guide to assist girls in self-reporting their age of development of breasts. Artificial cutoffs on reported age of development of breasts were not imposed and instead age of development of breasts was treated as a continuous construct. The mean age of development of breasts within this sample was M = 11.65 years (SD = 1.59).

Girls' Perceived Relative Pubertal Timing

Participants were asked two questions to assess girls' perceived relative pubertal timing. The first question focused on menarche: “Compared to other girls your age, did your period come (1) much earlier, (2) somewhat earlier, (3) about the same time, (4) somewhat later or (5) much later?” The second question focused on development of breasts: “Compared to other girls your age, do you consider your development of breasts to be (1) much earlier, (2) somewhat earlier, (3) about the same time, (4) somewhat later or (5) much later?” Studies have demonstrated reasonable reliability coefficients for girls' perceptions of their pubertal timing (Dubas et al., 1991; Graber et al., 1997). Graber et al. (1997), for example, found acceptable test-retest reliability of girls' perceived pubertal timing over 1-year (r = 0.61).

Procedure

The girls' caregivers completed the CBCL either during a scheduled school visit with the school social worker or during the girls' school admission intake. A female African American (the first author) at the school conducted interviews with all adolescents. Questions assessed the girls' perceived pubertal timing (menarche and development of breasts) and retrospective information about the girls' age of menarche and development of breasts. Upon completion of the interview, the adolescents completed the measures during school hours in small groups of about 8 to 10 participants. Although experimenter assistance in completing the measures was available, participants needed little or no assistance. A female teacher from the educational and counseling center, who served as the homeroom teacher for all the adolescents, completed the TRF for each adolescent.

Results

Table 1 presents proportions of the socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., youths' history of problem behavior), means, and standard deviations for the key continuous variables in the study for the total sample. No statistically significant differences were found. Three (2.9%) girls indicated they had not reached menarche and one (1%) indicated their breasts had not yet begun to develop; hence they were treated as providing missing data. Thirty-three percent perceived their breasts as developing at the same time as their peers and 35% perceived their age of menarche as developing at the same time as their peers.

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Proportions for Socio-demographics and Key Study Variables for the Total Sample (N = 102).

| Source of the Rating Scale | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL | YSR | TRF | ||||||

| Variable | % | n | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Below grade level | 63 | 64 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Youths' history of substance use | 11 | 11 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Youths' history of drug use | 15 | 15 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Youths' history of physical abuse | 9 | 9 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Youths' history of running away | 29 | 30 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Parents' history of substance use | 31 | 32 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Parents' history of drug use | 28 | 29 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Anxiety/depression subscale | -- | -- | 56 | 8.1 | 57 | 8.1 | 56 | 6.5 |

| Withdrawn subscale | -- | -- | 57 | 9.9 | 58 | 9.8 | 60 | 8.3 |

| Delinquency subscale | -- | -- | 63 | 8.2 | 61 | 8.4 | 65 | 9.4 |

| Internalizing behavior subscale | -- | -- | 55 | 13.2 | 55 | 11.1 | 56 | 8.4 |

| Externalizing behavior subscale | -- | -- | 56 | 12.2 | 56 | 12.1 | 62 | 10.5 |

Note: CBCL = parent report; TRF = teacher report form; YSR = youth self report

Preliminary analyses showed no notable non-normality and no outliers. Missing data was minimal and imputations were made using Expectation-Maximization (EM) approach. Table 2 presents the correlations between behavioral and emotional problems as reported by different sources. In general, the correlations were low; a result that was expected and that is consistent with past research. These correlations justify treating the reports from different sources as separate outcomes.

Table 2. Correlations Between Reports from Different Sources.

| Teacher Report Anxiety/Depression | Parent Report Anxiety/Depression | |

|---|---|---|

| Child Report Anxiety/Depression | - 0.035 | 0.258* |

| Parent Report Anxiety/Depression | 0.079 | - |

| Teacher Report Withdrawn | Parent Report Withdrawn | |

| Child Report Withdrawn | - 0.084 | 0.153 |

| Parent Report Withdrawn | 0.229* | - |

| Teacher Report Delinquency | Parent Report Delinquency | |

| Child Report Delinquency | 0.276** | 0.162 |

| Parent Report Delinquency | 0.063 | - |

| Teacher Report Internalizing | Parent Report Internalizing | |

| Child Report Internalizing | - 0.023 | 0.234* |

| Parent Report Internalizing | 0.249* | - |

| Teacher Report Externalizing | Parent Report Externalizing | |

| Child Report Externalizing | 0.402** | 0.013 |

| Parent Report Externalizing | - 0.033 | - |

Note:

p < 0.05;

p < 0.001

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

Because of the large number of outcome variables, two separate models on conceptually driven groups of outcomes were pursued, one focused on delinquency, social withdrawal, and depression/anxiety and the second focused on externalizing/internalizing outcomes. Each set of analyses are discussed, in turn.

Delinquency, Withdrawn, and Depression/Anxiety

A variant of the path model in Figure 1 was tested, which differed from it in the following ways: (1) The three outcome variables for each source (teacher, adolescent, parent) were included in the model, (2) chronological age was included as a covariate for all endogenous variables, and (3) direct causal paths were included from girls' retrospective reports of menarche and development of breasts directly to each outcome (i.e., girls' perceived relative menarche and perceived relative development of breasts were modeled as only partial mediators rather than complete mediators of these effects). Correlated errors for the outcomes were permitted within a source but not across sources.

The overall fit of the model was good. The chi square for model fit was nonsignificant (chi square = 30.6, df = 29, p < 0.39) and all of the traditional indices of overall fit were satisfactory (GFI = 0.96; CFI = 0.99 RMSEA = < 0.02; close fit test p value < 0.71; standardized RMR = 0.02). In addition, more focused fit tests all suggested good fit.

The social deviance model predicts that the relation between the pubertal development variables and outcome variables will be nonlinear in form, with early and late developers showing higher propensities for negative outcomes. This possibility was tested using polynomial regression methods that added both quadratic and cubic terms as potential predictors to all cases where a given maturation variable was predicting an endogenous variable. In no case did the cubic terms yield a statistically significant result, nor did any of the quadratic terms when the cubic terms were dropped from the linear equation.

Rows 1 through 5 of Table 3 present the key path coefficients. Girls' retrospective reports of age of menarche were predictive of girls' perceived age of menarche (controlling for age); such that earlier age of menarche was associated with perceptions that one achieved menarche earlier than one's peers. Later ages of menarche were also associated with perceptions that one achieved menarche later than one's peers. Interestingly, such a relation was not observed for girls' retrospective reports of development of breasts. That is, the girls' retrospective reports of development of breasts were not significantly associated with their perceptions that they started developing breasts earlier or later than their peers.

Table 3. Selected Path Coefficients for the Analysis of Delinquency, Withdrawn, and Depression/Anxiety and for the Analysis of Internalizing and Externalizing.

| Path |

Unstandardized Coefficient |

Standardized Coefficient |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retrospective menarche to perceived menarche | 0.35 | 0.36 | <0.01 |

| Retrospective development of breasts to perceived development of breasts | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.31 |

| Perceived development of breasts to teacher report – Delinquency | -1.49 | -0.22 | 0.05 |

| Retrospective menarche to teacher report - Delinquency | -1.81 | -0.23 | 0.08 |

| Perceived menarche to parent report - Delinquency | 1.45 | 0.21 | 0.08 |

| Retrospective development of breasts to teacher report -Internalizing | -11.59 | na | 0.02 |

| Squared retrospective development of breasts to teacher report – Internalizing | 0.56 | na | <0.01 |

| Retrospective menarche to teacher report - Internalizing | -1.91 | -0.23 | 0.05 |

| Perceived development of breasts to teacher report – Externalizing | -1.50 | -0.18 | 0.08 |

With respect to the teachers' reports of the girls' delinquency, girls who perceived their breasts as developing earlier than their peers were rated significantly higher in delinquency than girls who perceived their breasts as developing on-time or later than their peers (controlling for age). Two effects that approached significance also involved the outcome of delinquency but in relation to girls' retrospective age of menarche, as reported by the teachers and parents. With respect to the teachers' reports of the girls' delinquency, girls' who self-reported an earlier age of menarche than their peers were rated significantly higher in delinquency than girls who self-reported an on-time or later age of menarche (controlling for age). With respect to the parents' reports of girls' delinquency, girls who perceived their age of menarche earlier than their peers were rated significantly lower in delinquency than girls who perceived their age of menarche as either on-time or later than their peers (controlling for age).

Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior Problems

The same SEM model described above was tested but using the outcomes of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems as assessed on the Achenbach scales, as rated by the adolescents, teachers, and parents. Using the same approach as earlier, one quadratic term was found to be statistically significant; hence, it was included in the SEM analysis. The overall fit of the model was good. The chi square for model fit was nonsignificant (chi square = 17.84, df = 18, p < 0.47) and all the traditional fit indices were satisfactory (GFI = 0.97; CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = <0.01; close fit test p value < 0.72; standardized RMR = 0.02). Rows 6 through 9 of Table 3 present path coefficients that linked the sexual maturation variables to the outcomes that achieved statistical significance or were near statistical significance.

Row 6 represents the nonlinear effect noted above. The quadratic effect was observed between girls' retrospective reports of development of breasts and teacher reported internalizing (controlling for age). Using decompositional methods discussed in Jaccard, Wan, and Turrisi (1990), results revealed a J shaped relationship, with internalizing behavior problems achieving a minimum when development of breasts was reported starting at age 10.4 years. After that time, increasingly later ages of development of breasts were associated with accelerated internalizing problems as reported by the teacher. Prior to the age of 10.5 years, reported earlier ages of development of breasts had more minimal impact on internalizing, but as one moved to very early ages (e.g., 7 or 8 years) internalizing behavior problems showed a definite upward trend. This result is consistent with the social deviance theory.

All of the path coefficients in Table 3 that achieved statistical significance were statistically significant without the Holm's-based modified Bonferroni correction. When Holm's modified Bonferroni tests were invoked, the effects that remained statistically significant were the girls' retrospective reports of menarche to perceive menarche path, the girls' perceive development of breasts to teacher reported delinquency path, and the curvilinear effect of girls' retrospective reports of development of breasts to teacher reported internalizing path.

Discussion

Although menarche is the most commonly used index of puberty, results of this study suggest significant effects of pubertal timing on girls' psychosocial adjustment using development of breasts as an independent indicator, not just menarche. The study's findings further emphasize the importance of including both girls' retrospective reports of pubertal timing and girls' perceived relative pubertal timing when interpreting timing effects on girls' psychosocial adjustment. Girls' retrospective reports of menarche were significantly related to girls' perceived menarche; whereas girls' retrospective reports of development of breasts were not related to their perceived development of breasts. Lastly, the results highlight the importance of including teacher reports of girls' emotional and behavioral problems in this area of research.

The results of the present study are consistent with previous studies on European American adolescent girls (Graber et al., 1997; Swarr & Richards, 1996) and adolescent girls of color (Siegel et al., 1999), which used perceived pubertal timing to assess pubertal timing. Girls who perceived their developing breasts as early relative to their peers were more likely to engage in delinquent behaviors according to teacher report. Results vary from previous findings because the link between early pubertal timing and girls' delinquent behaviors was established in the present study using a single pubertal indictor (i.e., development of breasts) of girls' perceived pubertal timing; past research combined multiple pubertal indicators (e.g., development of breasts, skins changes, growth spurt).

This finding contrasted with the study hypotheses that early and late perceived relative pubertal timing would influence behavioral and emotional problems in African American adolescent girls. Instead, it appears that African American girls who perceive their developing bodies (i.e., breasts) to be early may be exposed to older peers, some of whom may be delinquent, and engage in non-normative behaviors (Caspi & Moffitt, 1991; Stattin & Magnusson, 1990). Perceived early development of breasts may therefore change the social context of African American adolescent girls, in part, from their tendency to match their behavior to that of their older peers. These behaviors observed in older peers may appear appropriate to early developing girls given their physical appearance, but are inappropriate given the girls' level of cognitive and coping abilities.

Results of this study also demonstrated significant effects of teacher reported internalizing problems among girls who retrospectively reported their breasts developing either early or late compared to girls who retrospectively reported their breasts developing on-time. This finding is consistent with previous studies on European American adolescent girls (e.g., Brooks-Gunn et al., 1994; Caspi & Moffitt, 1991; Petersen & Crocket, 1985; Susman, Dorn, & Chrousos, 1991) and African American adolescent girls (Ge et al., 2002; Ge et al., 2003). The present study's results go beyond past research, however, because the findings focused not only on the influence of early pubertal timing but also on the influence of late pubertal timing. Research is sparse on the effects of late pubertal timing on girls' psychosocial adjustment relative to research on the effects of early pubertal timing on girls' psychosocial adjustment (Dorn, Susman, & Ponirakis, 2003; Martin, 1996; Michael & Eccles, 2003; Striegel-Moore et al., 2001). It thus is of interest that late pubertal timing was found to be similarly problematic as early pubertal timing with respect to internalizing problems in this sample of African American adolescent girls. The observed link between late pubertal timing and girls' internalizing problems may reflect social and contextual factors not apparent in European American girls. It is possible that African American girls whose breasts develop later than their peers feel dissatisfied with the pace of their developing bodies due to their bodies' childlike appearance. As such, the cultural benefits that may accrue from breast development may not yet be realized by late breast developing African American girls (Parker et al., 1995; Rucker & Cash, 1992; Thompson, Sargent, & Kemper, 1996).

Interestingly, a clear pattern emerged from the study findings regarding both the Stage Termination Hypothesis and the Social Deviance Hypothesis. The Stage Termination Hypothesis supports perceived relative pubertal timing (breasts) effects on adjustment difficulties in the externalizing (i.e., delinquency) behavioral domain. African American adolescent girls who perceive their development of breasts as early may interact with older peers, particularly older males, for whom behaviors such as truancy are already normative. Perhaps early developing girls in this study were involved in problem behaviors before they developed the necessary coping skills to manage interactions involving older peers.

The Social Deviance Hypothesis was supported however by the girls' retrospective reports of their pubertal timing (breasts) effects on their adjustment difficulties in the internalizing (i.e., anxiety, depression) domain. African American adolescent girls whose breasts developed earlier than their peers may feel upset that they are experiencing these external changes in temporal isolation from their peers. Further, late developing African American girls may be rejected by their peers. This may be particularly relevant if the immediate peer group for girls in this sample is other African American girls with similar sociocultural standards of beauty.

Another notable result is the failure to find a significant link between girls' retrospective reports of menarche and girls' perceived menarche and girls' behavioral and emotional problems in this sample of African American girls. Given some path coefficients approached significance (e.g., girls' retrospective reports of menarche to teacher report of delinquency), our sample may have been too heterogeneous (ethnocultural) to examine fully the role of retrospective self-reports and perceived menarche on girls' psychosocial adjustment. Nevertheless, the study's findings illustrate that the development of breasts may have stronger effects on psychosocial functioning in African American adolescent girls than menarche. The individual effects of development of breasts on girls' psychosocial outcomes remain relatively unexplored in the puberty literature. Further research is needed to delineate the mechanisms through which development of breasts lead some African American adolescent girls to subsequent maladjustment.

There are several study limitations that should be noted. First, the study relied primarily on self-report data measures to assess girls' retrospective reports of pubertal timing and perceived relative pubertal timing. Although most studies in this area of research have used adolescent self-report data to assess girls' pubertal timing, recent findings from Dorn et al. (2003) demonstrate that the effects of pubertal timing on adolescent psychosocial adjustment vary depending upon who rates the adolescents' pubertal development (i.e., parent, adolescent, physician). Future studies should include an even broader source assessment approach than that used in this study. Second, the present study was cross-sectional. It is unclear whether the observed link between girls' retrospective reports of pubertal timing and perceived relative pubertal timing and girls' delinquent and internalizing problems has implications for long-term adjustment problems.

Third, other factors not measured in this study could have accounted for variance when interacting with the measure of pubertal timing. For example, Caspi and Moffitt (1991) proposed that prior problem behaviors in adolescent girls lead to greater psychosocial adjustment problems in early developing girls, not early pubertal timing per se. In addition, the study findings may differ as a function of acculturation and enculturation factors. Certainly, the discontinuity between cultural values in the family and those of the extrafamilial settings such as schools may provide challenges with implications for girl's psychosocial adjustment. Indeed, African American adolescent girls may experience additional stress related to living in the United States as an ethnic minority and discrimination that is not experienced by European American adolescent girls.

A final limitation lies with the study's method of assessing girls' retrospective reports of pubertal timing and perceived relative pubertal timing using age at development of breasts. Although few studies have used development of breasts as a means to assess pubertal timing, many studies use menarche to examine the effects of pubertal timing on behavior. Given research findings have shown ethnic differences in standards of physical attractiveness (Halpern et al., 1999; Hayward, Gotlib, Schraedley, & Fitt, 1999), we felt examining the external physical changes linked to puberty in African American adolescent girls would help to clarify the inconsistent findings in the existing literature on samples of African American girls. Additional research is needed using age of development of breasts as the pubertal timing indicator to examine its effects on behavioral and emotional problems in adolescent girls, particularly African American girls. Moreover, future research is needed to determine whether the results of this study generalize to other ‘at-risk’ African American adolescent girls living in urban and rural environments.

Despite these limitations, this study adds to the relatively small body of literature linking girls' retrospective reports of pubertal timing and perceived relative pubertal timing to emotional and behavioral problems in African American adolescent girls (Ge et al., 2002; Ge et al., 2003; Michael & Eccles, 2003; Siegel et al., 1999; Striegel-Moore et al., 2001). The present findings go beyond past work because they highlight the importance of both early and late retrospective self-reports and perceived relative pubertal timing, the use of external and internal indicators of puberty, and the use of different informants of adolescent girls' emotional and behavioral problems.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a PRIME (Psychology Research Initiatives Mentorship Experience) Fellowship sponsored by the American Psychological Association and the National Institute for General Medicines to Rona Carter. We gratefully acknowledge the cooperation and contributions of the young adolescents who participated in the research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Rona Carter, Child and Family Psychosocial Research Center, Child Anxiety and Phobia Program (CAPP), Department of Psychology, University Park Campus, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199. rcart003@fiu.edu, (305) 348-1937, fax: (305) 348-1939

James Jaccard, Florida International University, Department of Psychology, University Park Campus, Miami, FL 33199. jjaccard@gmail.com, (305) 348-2064, fax: (305) 348-3879

Wendy K. Silverman, Child and Family Psychosocial Research Center, Child Anxiety and Phobia Program (CAPP), Department of Psychology, University Park Campus, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199. silverw@fiu.edu, (305) 348-2064, fax: (305) 348-1939

Armando A. Pina, Arizona State University, Department of Psychology, PO Box 871104, Temple, AZ 85287-1104. apina01@asu.edu, (480) 965-0357, fax: (480) 965-8544

References

- Achenbach TM. Program manual for the 1991 child behavior checklist/4-18 profile. Burlington, VT: University Associates in Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. The child behavior checklist and related instruments. In: Maruish ME, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. 2nd. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 1999. pp. 429–466. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Checklist. Burlington, VT: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaker FD. Pubertal timing, overweight, and psychological adjustment. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1992;12:396–419. [Google Scholar]

- Alsaker FD. Timing of puberty and reaction to pubertal changes. In: Rutter M, editor. Psychosocial disturbances in young people: Challenges for prevention. Cambridge, U. K.: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 37–82. [Google Scholar]

- Alsaker FD. Annotation: the impact of puberty. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1996;37:249–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisaga K, Petkova E, Cheng J, Davies M, Feldman J, Whitaker A. Menstrual functioning and psychopathology in a county-wide population of high school girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:1197–1204. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200210000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Newman DL, Holderness C, Warren MP. The experiences of breast development and girls' stories abut the purchase of a bra. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1994;23:539–565. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP. Measuring physical status and timing in early adolescence: A developmental perspective. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1985;14:163–189. doi: 10.1007/BF02090317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP, Rosso J, Gargiulo J. Validity of self-report measures of girls' pubertal status. Child Development. 1987;58:829–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan CM, Eccles JS, Becker JB. Are adolescents the victims of raging hormones? Evidence for activational effects of hormones on moods and behavior at adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;111:62–107. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A. Puberty and the gender organization of schools: How biology and social context shape the adolescent experience. In: Crockett LJ, Crouter AC, editors. Pathways through adolescence: Individual development in relation to social contexts The Penn State series on child & adolescent development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1995. pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Individual differences as accentuated during periods of social changes: the sample case of girls at puberty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:157–168. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly SD, Paikoff RL, Buchanan CM. Puberty: the interplay of biological and psychosocial processes in adolescence. In: Adams GR, Montemayor R, Gullota TP, editors. Psychosocial development during adolescence: progress in developmental contextualism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. pp. 259–299. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn LD, Susman EJ, Ponirakis A. Pubertal timing and adolescent adjustment and behavior: Conclusions vary by rater. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2003;32:157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Dubas JS, Graber JA, Petersen AC. A longitudinal investigation of adolescents' changing perceptions of pubertal timing. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:580–586. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ. Timing of pubertal maturation in girls: An integrated life history approach. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:920–958. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Brody GH, Conger RD, Simons RL, Murray V. Contextual amplification of pubertal transition effects on deviant peer affiliation and externalizing behavior among African American children. Developmental Psychology. 2002;39:430–439. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Coming of age too early: Pubertal influences on girls' vulnerability to psychological distress. Child Development. 1996;67:3386–3400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:404–417. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Kim IJ, Brody GH, Conger RD, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Cutrona CE. It's about timing and change: Pubertal transition effects on symptoms of major depression among African American youths. Developmental Psychology. 2003;38:42–54. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP. The antecedents of menarcheal age: Heredity, family environment, and stressful life events. Child Development. 1995;66:346–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Brooks-Gunn J. Is psychopathology associated with the timing of pubertal development? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:1768–1776. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199712000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Udry JR, Campbell B, Suchindran C. Effects of body fat on weight concerns, dating, and sexual activity: A longitudinal analysis of black and white adolescent girls. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:721–736. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.3.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward C. Methodological concerns in puberty-related research. In: Hayward C, editor. Gender differences at puberty. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward C, Gotlib IH, Schraedley MA, Fitt IF. Ethnic differences in the association between pubertal status and symptoms of depression in adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;25:141–149. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Giddings ME, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC, Bourdony CJ, Bhapkar MV, Koch GG, Hasemeier CM. Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in an office practice: A study from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings network. Pediatrics. 1997;99:505–512. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Wan C, Turrisi R. The detection and interpretation of interaction effects between continuous variables in multiple regression. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:467–478. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2504_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latinen-Krispijn S, Van der Ende J, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AAJM, Verhulst FC. Pubertal maturation and the development of behavioral and emotional problems in early adolescence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1999;99:16–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb05380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin KA. Puberty, sexuality and the self: Girls and boys at adolescence. New York: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Michael A, Eccles JC. When coming of age means coming undone: Links between puberty and psychosocial adjustment among European American and African American girls. In: Hayward C, editor. Gender differences at puberty. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 277–303. [Google Scholar]

- Parker S, Nichter M, Vuckovic N, Sims C, Ritenbaugh C. Body-image and weight concerns about African American and white adolescent females-differences that make a difference. Human Organization. 1995;54:103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Peskin H, Livson N. Pre-and post-pubertal personality and adult psychological functioning. Seminars in Psychiatry. 1972;4:343–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crocket LJ. Pubertal timing and grade effects on adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1985;14:191–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02090318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Taylor B. Puberty: biological change and psychological adaptation. In: Adelson J, editor. Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York: Wiley; 1980. pp. 117–158. [Google Scholar]

- Rucker CE, Cash TF. Body images, body size perceptions, and eating behaviors among African American and white college woman. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1992;12:291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JM, Yancey AK, Aneshensel CS, Schuler R. Body image, perceived pubertal timing, and adolescent mental health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;25:155–165. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slap GB, Khalid N, Paikoff RL, Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP. Evolving self-image, pubertal manifestations, and pubertal hormones: Preliminary findings in young adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1994;15:327–335. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(94)90606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Magnusson D. Pubertal development in female development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, McMahon RP, Biro FM, Schreiber G, Crawford PB, Voorhees C. Exploring the relationship between timing of menarche and eating disorders symptoms in black and white adolescent girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;30:421–433. doi: 10.1002/eat.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susman EJ, Dorn LD, Chrousos GP. Negative affect and hormone levels in young adolescents: concurrent and predictive perspectives. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20:167–190. doi: 10.1007/BF01537607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarr AE, Richards MH. Longitudinal effects of adolescent girls' pubertal development, perceptions of pubertal timing, and parental relations on eating problems. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:636–646. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner JM. Sequence, tempo, and individual variation in growth and development of boys and girls aged 12 to 16. In: Kagan J, Coles R, editors. Twelve to sixteen: Early adolescence. New York: Norton; 1972. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SH, Sargent RG, Kemper KA. Black and white adolescent males' perceptions of ideal body size. Sex Roles. 1996;34:391–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity – A supplemental to mental health: A report of Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse, and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]