Abstract

Previous studies have shown declining rates of pulpal anesthesia over 60 minutes when a cartridge of 4% articaine is used with 1∶100,000 epinephrine for buccal infiltration in the mandibular first molar. The authors conducted a prospective, randomized, single-blind, crossover study comparing the degree of pulpal anesthesia obtained with 2 sets of mandibular first molar buccal infiltrations, given in 2 separate appointments, to 86 adult subjects: an initial infiltration of a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine plus a repeated infiltration of the same anesthetic and dose given 25 minutes following the initial infiltration versus an initial infiltration of a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine plus a mock repeated infiltration given 25 minutes following the initial infiltration. The authors used an electric pulp tester to test the first molar for anesthesia in 3-minute cycles for 112 minutes after the injections. The repeated infiltration significantly improved pulpal anesthesia from 28 minutes through 109 minutes in the mandibular first molar. A repeated infiltration of a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine given 25 minutes after an initial infiltration of the same type and dose of anesthetic significantly improved the duration of pulpal anesthesia, when compared with only an initial buccal infiltration, in the mandibular first molar.

Keywords: Infiltration, Articaine, Mandibular, Repeated infiltration

INTRODUCTION

Infiltration anesthesia is a common method used to anesthetize maxillary teeth. However, only recently has infiltration with an articaine formulation been used to anesthetize mandibular first molars.1–4

In 2000, articaine was introduced in the United States.5 Haas and colleagues6,7 compared infiltrations of 4% articaine and 4% prilocaine formulations in the mandibular canines and second molars. They found no statistical differences between the 2 anesthetic formulations. Success rates (achieving a pulp test reading of 80) were 65% for the canine infiltration and 63% for the second molar infiltration when a 4% articaine formulation was used. Kanaa and colleagues1 compared a cartridge of 2% lidocaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine versus a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine for buccal infiltration anesthesia of the mandibular first molar. The articaine formulation had a significantly higher success rate (achieving 2 consecutive pulp test readings of 80) of 64% when compared with the 39% success rate of the lidocaine formulation. Jung et al3 (achieving 2 consecutive pulp test readings of 80) reported a success rate of 54% using a buccal infiltration of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine in mandibular first molars. Corbett et al4 (achieving 2 consecutive pulp test readings of 80) had success rates that ranged from 64% to 70% when using articaine as a buccal infiltration of the mandibular first molar. They did not find a difference between buccal and buccal plus lingual infiltrations using articaine. Robertson and colleagues2 compared the degree of pulpal anesthesia achieved with mandibular first molar buccal infiltrations of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine and 2% lidocaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine. They found, using a lidocaine formulation, successful pulpal anesthesia (achieving 2 consecutive pulp test readings of 80) was 57% for the first molar. When the articaine formulation was used, successful pulpal anesthesia was 87%. A significant difference (P < .05) was reported between the 2% lidocaine and 4% articaine formulations. Therefore, 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine is superior to 2% lidocaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine in mandibular buccal infiltration of the first molar. However, Robertson and colleagues2 found that pulpal anesthesia with both the 4% articaine and 2% lidocaine formulations declined slowly over 60 minutes. Therefore, when only an initial infiltration is used, duration of pulpal anesthesia can be a significant clinical problem in the mandibular first molar if pulpal anesthesia is required for 60 minutes.

In the anterior maxilla, Scott et al8 found that a repeated infiltration of 1.8 mL of 2% lidocaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine given 30 minutes following the initial infiltration significantly improved the duration of pulpal anesthesia in the maxillary lateral incisor. No objective study has addressed the addition of a repeated infiltration of articaine after an initial infiltration to increase the duration of pulpal anesthesia in the mandibular first molar.

The purpose of this prospective, randomized, single-blind, crossover study was to compare the degree of pulpal anesthesia obtained with 2 sets of mandibular, first molar infiltrations: an initial buccal infiltration of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine plus a repeated buccal infiltration of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine given 25 minutes following the initial infiltration versus an initial buccal infiltration of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine plus a mock, repeated buccal infiltration given 25 minutes following the initial infiltration. We also recorded the pain of injection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eighty-six adult subjects participated in this study. All subjects were in good health and were not taking any medication that would alter pain perception as determined by a written health history and oral questioning. Exclusion criteria were as follows: younger than 18 or older than 65 years of age; allergies to local anesthetics or sulfites; pregnancy; history of significant medical conditions (American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] Class II or higher); taking any medications (over-the-counter pain-relieving medications, narcotics, sedatives, antianxiety or antidepressant medications) that may affect anesthetic assessment; active sites of pathosis in area of injection; and inability to give informed consent. The Ohio State University Human Subjects Review Committee approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from each subject.

Under a crossover design, 86 subjects received 2 sets of mandibular first molar infiltrations at 2 separate appointments spaced at least 1 week apart. The 2 sets of injections consisted of (1) an initial buccal infiltration of a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine plus a repeated buccal infiltration of a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine given 25 minutes following the initial infiltration, and (2) an initial buccal infiltration of a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine plus a repeated, mock buccal infiltration given 25 minutes following the initial infiltration.

With the crossover design, 172 infiltrations were administered for the first molar and each subject served as his or her own control. Forty-three sets of infiltration injections were administered on the left side and 43 sets of infiltrations were administered on the right side. The same side chosen for the first infiltration was used again for the second infiltration. The mandibular contralateral canine was used as the control to ensure that the pulp tester was operating properly and that the subject was responding appropriately. A visual and clinical examination was conducted to ensure that all teeth were free of caries, large restorations, crowns, and periodontal disease, and that none had a history of trauma or sensitivity.

Before the injections were given at both appointments, the experimental tooth and the contralateral canine (control) were tested 3 times with the electric pulp tester (Analytic Technology Corp, Redmond, Wash) to obtain baseline information. The teeth were isolated with cotton rolls and dried with an air syringe. Toothpaste was applied to the probe tip, which was placed in the middle third of the buccal surface of the tooth being tested. The value at the initial sensation was recorded. The current rate was set at 25 seconds to increase from no output (0) to maximum output (80). Trained personnel, who were blinded to the infiltration injections, administered all preinjection and postinjection tests.

Before the experiment, the 2 sets of infiltration injections were randomly assigned 6-digit numbers from a random number table. Each subject was randomly assigned to each of the 2 sets of injections to determine which injection set was to be administered at each appointment. Only the random numbers were recorded on the data collection sheets to further blind the experiment.

Before the injection was given, each subject was instructed on how to rate the pain for each phase of the injection: needle insertion, needle placement, and deposition of anesthetic solution using a Heft-Parker visual analogue scale (VAS).9 The VAS was divided into 4 categories. No pain corresponded to 0 mm. Mild pain was defined as greater than 0 mm and less than or equal to 54 mm. Mild pain included the descriptors of faint, weak, and mild pain. Moderate pain was defined as greater than 54 mm and less than 114 mm. Severe pain was defined as equal to or greater than 114 mm. Severe pain included the descriptors of strong, intense, and maximum possible. During each phase of the injection, the principal investigator informed the subject when each phase of the injection was complete. Immediately after the infiltration, the subject rated the pain for each injection phase on the VAS.

Before each injection was given, topical anesthetic gel (20% benzocaine, Patterson Dental Supply Inc, St Paul, Minn) was passively placed with a cotton tip applicator for 60 seconds at the injection site. A mandibular infiltration injection was administered with an aspirating syringe and a 27-gauge 1½″ needle (Monoject, St Louis, Mo) using a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine (Septocaine, Septodont, New Castle, Del). The target site was centered over the buccal root apices of the mandibular first molar. The 27-gauge needle was gently placed into the alveolar mucosa (needle insertion phase) and advanced within 2 to 3 seconds until the needle was estimated to be at or just superior to the apices of the tooth (needle placement phase). The anesthetic solution was deposited over a period of 1 minute (solution deposition phase). All infiltrations were given by the senior author (L.P.).

The depth of anesthesia was monitored with the electric pulp tester. At 1 minute after the initial infiltration injection, pulp test readings were obtained for the mandibular first molar. At 3 minutes, the contralateral mandibular canine was tested. The testing continued in 3-minute cycles for a total of 25 minutes. At every third cycle, the control tooth, the contralateral canine, was tested by an inactivated electric pulp tester to test the reliability of the subject. That is, if subjects responded positively to an inactivated pulp tester, then they were not reliable and could not be used in the study.

At 25 minutes after the initial infiltration, a repeated infiltration or a mock infiltration was given. New needles were used for both mock and repeated injections. The repeated infiltration was given at the same site and in the same manner as the initial infiltration using a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine. The mock infiltration used a standard syringe with a 27-gauge 1½″ needle. The needle normally engaging the anesthetic cartridge was bent over so it did not enter the rubber diaphragm. The mock infiltration mimicked the repeated infiltration using the same time period as was used for the repeated infiltration. However, there was only needle penetration into the alveolar mucosa. We did not inject saline because it may have diluted the initial anesthetic solution given 25 minutes earlier. Additionally, we do not believe that the deposition of a liquid would provide a greater degree of blinding because the subjects already had soft tissue anesthesia and would not perceive injection of the additional volume. All subjects were blindfolded during the repeated and mock infiltrations. Subjects rated needle insertion, needle placement, and solution deposition for the repeated and mock infiltrations, as was done for the initial infiltration. Pulp testing then commenced at the 28th minute and continued until the 112th minute so the length of time the repeated infiltration would provide pulpal anesthesia could be evaluated.

All subjects were asked to complete postinjection surveys after each appointment using the same VAS as was described previously, immediately after the numbness wore off, and again each morning upon arising for the next 3 days. Patients also were instructed to describe and record any problems, other than pain, that they experienced. Subjects' report of swelling was only subjective and was not based on any quantifiable measures.

No response from the subject at the maximum output (80 reading) of the pulp tester was used as the criterion for pulpal anesthesia. Anesthesia was considered successful when 2 consecutive 80 readings with the pulp tester were obtained within 10 minutes of the initial injection. With a nondirectional alpha risk of 0.05 and assumption of an anesthetic success rate of 60%, a ±15 percentage point difference in anesthetic success could be detected with a sample size of 86 subjects per group. The time for onset of pulpal anesthesia was recorded as the first of 2 consecutive 80 readings.

Between-group comparisons between initial and repeated infiltrations for anesthetic success were analyzed using the McNemar test. Incidence of anesthesia (80 readings) was analyzed using multiple McNemar tests with P values adjusted by using the step-down Bonferroni method of Holm. Between-group comparisons for onset time, needle insertion, needle placement, solution deposition pain, and postoperative pain were made using multiple Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks tests with P values adjusted by using the step-down Bonferroni method of Holm. Comparisons were considered significant at P < .05.

RESULTS

Eighty-six adult subjects, 43 men and 43 women ranging in age from 20 to 41 years, with an average age of 26 years, participated in this study.

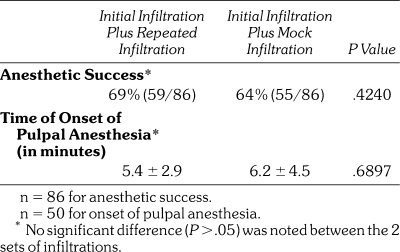

Table 1 demonstrates the percentages of successful pulpal anesthesia. For both initial infiltrations, anesthetic success ranged from 64 to 69%. No significant difference (P = .4240) was noted between the initial infiltration injections. The time of onset of pulpal anesthesia for the 2 initial infiltrations ranged from 5.4 to 6.2 minutes (Table 1). No significant difference (P = .6897) was observed between the initial infiltration injections.

Table 1.

Percentages and Numbers of Subjects Who Experienced Anesthetic Success and the Time of Onset of Pulpal Anesthesia for the 2 Sets of Infiltrations

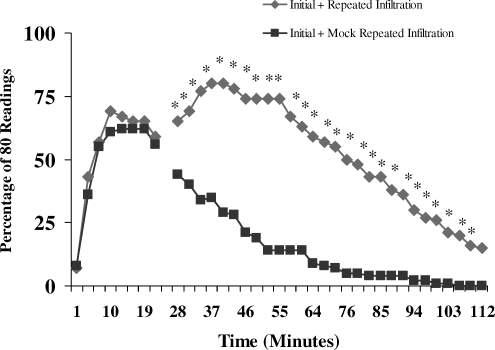

The incidence of pulpal anesthesia (80 readings across time) for the 2 sets of infiltrations is presented in the Figure. The repeated infiltration injection statistically improved pulpal anesthesia from 28 minutes through 109 minutes.

Incidence of mandibular first molar pulpal anesthesia as determined by lack of response to electrical pulp testing at the maximum setting (percentage of 80 readings), at each postinjection time interval, for the repeated infiltration and mock infiltration. Significant differences are marked with asterisks.

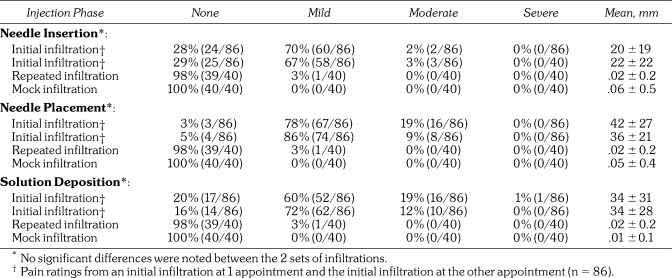

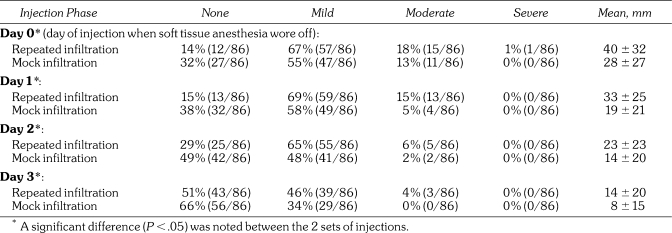

The pain of injection is presented in Table 2. None of the repeated infiltrations, or mock infiltrations, produced moderate or severe pain; only 1 incidence of mild pain was reported. Postoperative pain ratings are presented in Table 3. For the repeated infiltration, 22% (19/86) reported tenderness, and 22% (19/86) reported tenderness with the mock infiltration. Sixteen percent (14/86) reported slight swelling with repeated infiltration, and 9% (8/86) reported slight swelling with the mock infiltration.

Table 2.

Pain Ratings for Each Injection Phase for the 2 Sets of Infiltrations

Table 3.

Postinjection Pain Ratings for the 2 Sets of Infiltrations (n = 86)

DISCUSSION

We based our use of the electric pulp test reading of 80—signaling maximum output—as a criterion for pulpal anesthesia on the studies of Dreven and colleagues10 and Certosimo and Archer.11 These studies10,11 showed that no patient response to an 80 reading ensured pulpal anesthesia in vital, asymptomatic teeth. Additionally, Certosimo and Archer11 demonstrated that electric pulp test readings of less than 80 resulted in pain during operative procedures in asymptomatic teeth. Therefore, using the electric pulp tester before beginning dental procedures on asymptomatic, vital teeth will provide the clinician a reliable indicator of pulpal anesthesia.

The success of the initial infiltrations of the articaine formulation was 64 to 69% (Table 1). Various authors1–4 have evaluated the success of mandibular first molar infiltrations, using asymptomatic subjects, a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine, and an electric pulp tester to evaluate pulpal anesthesia. Kanaa et al,1 Jung et al,3 Corbett et al,4 and Robertson et al2 used a similar method to that used in the current study and demonstrated 64%, 54%, 64 to 70%, and 87% success rates, respectively, for the buccal infiltration of the mandibular first molar. Except for the results of Robertson et al,2 our success rates of 64 to 69% are similar to those of the other studies. Therefore, the initial infiltration success rates would not be predictable in providing profound pulpal anesthesia. Further research needs to improve the success rate of mandibular first molar infiltration with an articaine formulation. Because we studied a young adult population, the results of this study may not apply to children or the elderly.

One solution to the lower success rate of the initial infiltration with articaine would be to combine the infiltration with an inferior alveolar nerve block. Haase et al12 added an infiltration of articaine or lidocaine in the mandibular first molar following an inferior alveolar nerve block in asymptomatic subjects. They found statistically higher success rates (2 consecutive 80 readings were obtained within 10 minutes following the inferior alveolar nerve block plus infiltration injections, and the 80 reading was continuously sustained through the 60th minute) of 88% with the articaine formulation compared with 71% for the lidocaine formulation. Kanaa et al13 also found that the inferior alveolar nerve block supplemented with a buccal articaine infiltration was more successful (92% success rate—2 consecutive 80 readings) than an inferior alveolar nerve block alone (56% success rate).

The time of onset of pulpal anesthesia averaged 5.4 to 6.2 minutes for the initial infiltrations (Table 1). Jung et al,3 Corbett et al,4 and Robertson et al,2 using 1 cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine, reported onset times for the mandibular first molar of 6.6 minutes, 6.5 minutes, and 4.2 minutes, respectively. Except for Robertson et al,2 the results of the current study are similar to the onset times recorded by the other 2 authors. In general, onset times for buccal infiltration of the mandibular first molar with a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine would range from 4 to 7 minutes. Pulp testing the tooth with an electric pulp tester or a cold refrigerant will give the clinician a reliable indicator of onset of pulpal anesthesia.

The Figure demonstrates the decline in pulpal anesthesia over 60 minutes for the initial infiltration plus the mock infiltration. For both sets of infiltrations, approximately 57% of subjects had pulpal anesthesia at 22 minutes. However, at 45 minutes, approximately 28% of subjects had pulpal anesthesia following the mock infiltration. At 60 minutes, only 14% had pulpal anesthesia. Robertson et al2 also showed a declining rate of pulpal anesthesia when using a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine for mandibular buccal first molar infiltrations. Therefore, when only an initial infiltration is used, duration of pulpal anesthesia could be a significant clinical problem in the mandibular first molar if pulpal anesthesia is required for 60 minutes.

The 25-minute time frame for the repeated infiltration was based on previous studies by Robertson et al2 showing that pulpal anesthesia for the mandibular first molar declined from initial high levels at 25 to 30 minutes. Naturally, a repeated infiltration could be administered before 25 minutes or after 25 minutes. Future research could evaluate anesthetic success with repeated infiltrations at different times.

The onset of pulpal anesthesia gradually increased for the initial injection and averaged around 5 minutes. Pulpal anesthesia for the repeated infiltration also showed a gradual onset of effect, with steadily increasing levels of pulpal anesthesia from 28 minutes until around 37 minutes (Figure).

The repeated infiltration of a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine significantly increased the incidence of pulpal anesthesia from 28 minutes through 109 minutes (Figure). At 45 minutes, approximately 78% of the subjects had pulpal anesthesia with the repeated infiltration compared with only 28% with the mock infiltration. As is shown in the Figure, pulpal anesthesia slowly declined after 60 minutes for the repeated infiltration, with approximately 50% of the subjects anesthetized at 75 minutes and 38% anesthetized at 90 minutes. In general, the repeated infiltration significantly increased the duration of pulpal anesthesia but would not provide predictable pulpal anesthesia because the initial infiltration was successful only 64 to 69% of the time. If the success of the initial injection could be increased, the addition of a repeated infiltration could provide a duration of pulpal anesthesia that would be clinically predictable. For example, Scott et al8 found that repeated infiltration of 1.8 mL of 2% lidocaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine given 30 minutes following the initial infiltration of the same type and amount of anesthetic significantly improved the duration of pulpal anesthesia (from 37 through 90 minutes) in the maxillary lateral incisor. The initial infiltration was successful (absence of response to 2 consecutive 80 readings) from 95 to 100% of the time. With only the initial infiltration, approximately 78% of the subjects had pulpal anesthesia at 30 minutes; at 45 minutes, approximately 60% of the subjects had pulpal anesthesia, and at 60 minutes, 33% had pulpal anesthesia. With the repeated infiltration, 90% of the subjects had pulpal anesthesia at 60 minutes. Therefore, the success of the initial injection will have a significant effect on the success of the repeated injection.

A drug's enhanced effectiveness when given repeatedly is referred to as augmentation.14,15 Tachyphylaxis is a declining effectiveness when a drug is given repeatedly.14,15 The Figure shows a higher level of pulpal anesthesia than occurred initially after administration of the repeated infiltration. If the repeated infiltration provided the same effect as the initial infiltration, we would not necessarily expect a higher incidence of pulpal anesthesia. Therefore, it would seem that augmentation might be occurring. A prime consideration in whether augmentation or tachyphylaxis occurs is timing.14,15 If an infiltration is given within a reasonable time as anesthesia wears off, augmentation is likely to occur.14,15 However, if the infiltration is given some time after anesthesia wears off, tachyphylaxis frequently occurs.14,15

Needle insertion for the initial infiltrations resulted in 2 to 3% of subjects reporting moderate pain and none reporting severe pain (Table 2). Robertson et al2 found the mean pain ratings following a buccal infiltration of a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine to be 24 mm, which is similar to our results (Table 2).

Needle placement pain for the initial infiltrations resulted in 9 to 19% of subjects reporting moderate pain and none reporting severe pain (Table 2). The mean pain rating was 34 to 42 mm (Table 2). Robertson et al2 reported an incidence of needle placement pain of 33 mm for an articaine formulation, which is similar to our results.

Solution deposition resulted in an incidence of 12 to 19% moderate pain and a 1% incidence of severe pain even though 1 minute was used to deposit the anesthetic solution (Table 2). The mean pain rating was 34 to 36 mm. Robertson et al2 found that an incidence of solution deposition pain was 36 mm, which is similar to our results. Kanaa et al1 and Corbett et al,4 using a similar design to the current study, found that pain ratings for buccal infiltration of the mandibular first molar were in the mild range. Therefore, in general, some moderate pain may be experienced with the buccal infiltration of a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine, but most subjects will have mild pain.

None of the repeated infiltrations, or mock infiltrations, produced moderate or severe pain; only 1 incidence of mild pain was reported. The most likely reason for this finding would be that soft tissue anesthesia from the initial infiltration was still present when the repeated injection was given 25 minutes later.

Postinjection pain ratings, at the time anesthesia wore off, were statistically different between repeated and mock infiltrations for day 0 through day 3 (Table 3). Because a 2-cartridge volume was deposited, more postinjection pain was experienced with the repeated infiltration. However, the mean pain ratings were still in the mild pain range and the incidence of pain decreased over the 3 days (Table 3). Robertson et al2 found that the mean pain ratings following a buccal infiltration of a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine for day 0, day 1, day 2, and day 3 were, respectively, 20 mm, 15 mm, 11 mm, and 5 mm. These mean pain values were a little lower than our results for the initial plus the mock infiltration but generally followed the pattern of decreasing pain over the 3 days (Table 3).

Postinjection complications reported were tenderness and slight swelling in the area of the injection. For the repeated infiltration, 22% (19/86) reported tenderness, and 22% (19/86) reported tenderness with the mock infiltration. Sixteen percent (14/86) reported slight swelling with repeated infiltration, and 9% (8/86) reported slight swelling with the mock infiltration. Robertson et al2 found that 4% of subjects reported swelling with the mandibular first molar buccal infiltration of a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine, which resolved by the third day. In the current study, most complications resolved within 3 days, except for 7 subjects who still reported tenderness and 5 who still reported slight swelling on day 3. Although paresthesia associated with articaine use has been reported,16–18 no subjects reported any paresthesia in our study even though the injection site approximated the mental nerve.

In conclusion, repeated infiltration of a cartridge of 4% articaine with 1∶100,000 epinephrine given 25 minutes after an initial infiltration of the same type and dose of anesthetic significantly improved the duration of pulpal anesthesia when compared with only an initial infiltration in the mandibular first molar.

REFERENCES

- Kanaa M.D, Whitworth J.M, Corbett I.P, Meechan J.G. Articaine and lidocaine mandibular buccal infiltration anesthesia: a prospective randomized double-blind cross-over study. J Endod. 2006;32:296–298. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson D, Nusstein J, Reader A, Beck M, McCartney M. The anesthetic efficacy of articaine in buccal infiltration of mandibular posterior teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:1104–1112. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y, Kim J.H, Kim E.S, Lee C.Y, Lee S.J. An evaluation of buccal infiltrations and inferior alveolar nerve blocks in pulpal anesthesia for mandibular first molars. J Endod. 2008;34:11–13. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett I.P, Kanaa M.D, Whitworth J.M, Meechan J.G. Articaine infiltration for anesthesia of mandibular first molars. J Endod. 2008;34:514–518. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamed S.F, Gagnon S, Leblanc D. Articaine hydrochloride: a study of the safety of a new amide local anesthetic. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:177–185. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas D.A, Harper D.G, Saso M.A, Young E.R. Lack of differential effect by Ultracaine (articaine) and Citanest (prilocaine) in infiltration anesthesia. J Can Dent Assoc. 1991;57:217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas D.A, Harper D.G, Saso M.A, Young E.R. Comparison of articaine and prilocaine anesthesia by infiltration in maxillary and mandibular arches. Anesth Prog. 1990;37:230–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Drum M, Reader A, Nusstein J, Beck M. The efficacy of a repeated infiltration in prolonging duration of pulpal anesthesia in maxillary lateral incisors. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:318–324. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heft M.W, Parker S.R. An experimental basis for revising the graphic rating scale for pain. Pain. 1984;19:153–161. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(84)90835-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreven L, Reader A, Beck M, Meyers W, Weaver J. An evaluation of the electric pulp tester as a measure of analgesia in human vital teeth. J Endod. 1987;13:233–238. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(87)80097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Certosimo A, Archer R. A clinical evaluation of the electric pulp tester as an indicator of local anesthesia. Oper Dent. 1996;21:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase A, Reader A, Nusstein J, Beck M, Drum M. Comparing anesthetic efficacy of articaine versus lidocaine as a supplemental buccal infiltration of the mandibular first molar after an inferior alveolar nerve block. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1228–1235. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaa M.D, Whitworth J.M, Corbett I.P, Meechan J.G. Articaine buccal infiltration enhances the effectiveness of lidocaine inferior alveolar nerve block. Int Endod J. 2009;42:238–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong R.H. Local Anesthetics. St Louis, Mo: Mosby-Year Book Inc; 1994. pp. 243–244. [Google Scholar]

- Choi R.H, Birknes J.K, Popitz-Bergez F.A, Kissin I, Strichartz G.R. Pharmacokinetic nature of tachyphylaxis to lidocaine: peripheral nerve blocks and infiltration anesthesia in rats. Life Sci. 1997;61:177–184. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00664-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas D.A, Lennon D. A 21 year retrospective study of reports of paresthesia following local anesthetic administration. J Can Dent Assoc. 1995;61:319–320. 323–326, 329–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller P, Lennon D. Incidence of local anesthetic-induced neuropathies in Ontario from 1994–1998 (abstract 3869) J Dent Res. 2000;79:627. [Google Scholar]

- Pogrel M.A. Permanent nerve damage from inferior alveolar nerve blocks—an update to include articaine. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:271–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]