Alternating hemiplegia of childhood (AHC) is a neurodevelopmental syndrome of uncertain etiology.1 It is characterized by onset of hemiplegic, tonic, or dystonic episodes occurring before the age of 18 months. Progressive ataxia and cognitive impairment are frequent. AHC has been reported to be caused by mutations in the ATP1A2 and the CACNA1A genes,2,3 but most cases of AHC remain genetically undiagnosed.

Glut1 deficiency syndrome (Glut1 DS, OMIM 606777) is a disorder of brain energy metabolism caused by impaired glucose transport into the brain mediated by the facilitative glucose transporter Glut1, encoded by the GLUT1 gene.4 The hallmark of the disease is low CSF glucose concentration.5 Classic presentation of Glut1 DS includes epilepsy, developmental delay, acquired microcephaly, cognitive impairment, spasticity, ataxia, and dystonia. Paroxysmal movement disorders with or without epilepsy have been described as well, such as paroxysmal episodes of abnormal head or eye movements, intermittent ataxia,4 and paroxysmal exercise-induced dyskinesias.5 The ketogenic diet may have a beneficial effect on symptom control and development.4

We report a child with AHC found to have a mutation in the GLUT1 gene.

Case report.

The patient is now 10 years old. There is no pertinent family history. The perinatal period and initial development were normal. He walked unassisted at 14 months and was noted to fall more frequently than his peers. At 2 years he began having episodes of ataxia and slurred speech, lasting for 10–15 minutes. From 2.5 years asymmetry was noted during the episodes, with right or left sided hemiplegia, unilateral facial weakness, and slurred speech lasting for 3–4 hours. The episodes included pallor and irritability. Upon awakening he was asymptomatic, and within an hour would start to show unilateral weakness. Episodes were mitigated or aborted by beverages or candy. There were no eye movement abnormalities. He was diagnosed with AHC. Treatment with flunarizine made the events milder and shorter. He has shown gradual cognitive deterioration. Current neuropsychologic evaluation showed full-scale IQ of 51. He has gradually developed a mild ataxic gait. Head circumference has decreased from the 50th percentile to below the third percentile. Brain MRI was normal. Two lumbar punctures showed CSF glucose concentrations of 35 and 39 mg/dL, and serum glucose concentrations of 99 and 80 mg/dL. CSF lactate was 1.07 mM. The ketogenic diet was poorly tolerated with severe weight loss. The patient is currently supplementing his diet with cornstarch, which has made the events milder and less frequent. We evaluated him at age 10 years for Glut1 DS.

Methods.

Erythrocyte 3-O-methyl-d-glucose uptake and GLUT1 mutational analysis were performed as described elsewhere.4

Results.

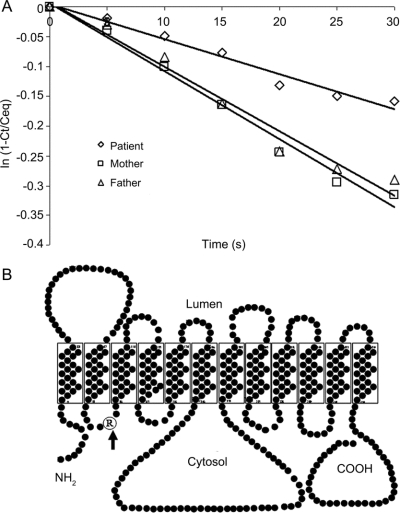

Patient uptake of 3-O-methyl-d-glucose was 53% (figure, A), Vmax for 3-O-methyl-d-glucose uptake was 52% (patient: 500 fmol/s/106 cells, controls:1,000 fmol/106 cells, 909 fmol/106 cells), and Km was 97% (patient: 1.3 mM, controls: 1.4 mM and 1.3 mM). GLUT1 mutational analysis revealed a single nucleotide replacement CGG>TGG at nucleotide 277, resulting in a heterozygous R93W missense mutation in exon 4. Parents’ analysis was normal. This mutation is located in the first cytosolic loop of Glut1 (figure, B). R93W or R93Q mutations have been described previously in Glut1 DS associated with a typical epileptic phenotype.6

Figure Glut1 protein: Functional and structural analysis

(A) 3-O-methyl-d-glucose uptake into red blood cells, which was performed as described elsewhere.4 Decreased uptake rate in patient is shown compared with parents serving as control. The data are expressed as the natural logarithm of the ratio of intracellular radioactivity at time T/equilibrium vs time in seconds (2 determinations/data point). (B) The proposed Glut1 protein configuration with the R93W mutation (arrow) situated in the first cytosolic loop.

Discussion.

AHC patients may have cerebral glucose deficiency. Low glucose metabolism was found in the frontal lobes, putamen, and cerebellum of patients with AHC as measured by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET.7 This pattern of cortical and cerebellar glucose hypometabolism also has been described in Glut1 DS.6 We describe a child with Glut1 DS presenting with episodes of alternating hemiplegia, progressive ataxia, cognitive deterioration, and decelerating head growth. Other than the episodes starting after the age of 18 months, the phenotype is typical for AHC.2 The hallmark of Glut1 DS is low CSF glucose concentration, usually below 40 mg/dL.4,5 A literature search of AHC cases failed to show CSF findings in this population. Episodes of AHC are triggered by physical activity, environmental stress, and certain foods but not by fasting.2 We recommend that children with AHC be tested for hypoglycorrhachia, especially if symptoms are induced by physical activity or fasting. If the glucose concentration is low, further evaluation as described in this case should be performed. Early treatment with the ketogenic diet should be considered in all children with Glut1 DS.

Disclosure: Dr. Rotstein receives research support from the Pediatric Neurotransmitter Disease Association (fellowship grant). Dr. Doran, Dr. Yang, Dr. Ullner, and Dr. Engelstad report no disclosures. Dr. De Vivo serves on scientific advisory boards for Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) Foundation, the Colleen Giblin Foundation, the Pediatric Neurotransmitter Disease Association, and the International Reye Syndrome Foundation; receives royalties from publishing The Molecular Basis and Genetic Basis of Neurologic and Psychiatric Disease, 4th ed. (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008); and receives research support from the NIH [1 UL1 RR024156-01 (investigator), NINDS 5K12NS01698 (program director) and 5R01NS37949 (PI), and NICHD 5P01HD32062 (PI)], the SMA Foundation, and the Colleen Giblin Foundation.

Received April 29, 2009. Accepted in final form August 19, 2009.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Darryl C. De Vivo, Columbia University, Neurological Institute, 710 West 168th Street, New York, NY 10032; dcd1@columbia.edu

&NA;

- 1.Sweney MT, Silver K, Gerard-Blanluet M, et al. Alternating hemiplegia of childhood: early characteristics and evolution of a neurodevelopmental syndrome. Pediatrics 2009;123:e534–e541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swoboda KJ, Kanavakis E, Xaidara A, et al. Alternating hemiplegia of childhood or familial hemiplegic migraine? A novel ATP1A2 mutation. Ann Neurol 2004;55:884–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Vries B, Stam AH, Beker F, et al. CACNA1A mutation linking hemiplegic migraine and alternating hemiplegia of childhood. Cephalalgia 2008;28:887–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang D, Pascual JM, Yang H, et al. Glut1 deficient syndrome: clinical, genetic, and therapeutic aspects. Ann Neurol 2005;57:111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Vivo DC, Wang D. Glut1 deficiency: CSF glucose. How low is too low? Rev Neurol Paris 2008;164:877–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pascual JM, Van Heertum RL, Wang D, Engelstad K, De Vivo DC. Imaging the metabolic footprint of Glut1 deficiency on the brain. Ann Neurol 2002;52:458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasaki M, Sakuma H, Fukushima A, Yamada K, Ohnishi T, Matsuda H. Abnormal cerebral glucose metabolism in alternating hemiplegia of childhood. Brain Dev 2009;31:20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]