Abstract

Increasing access to, and use of, health promotion strategies and health care services for diverse cultural groups is a National priority. While theories about the structural determinants of help seeking have received empirical testing, studies about cultural determinants have been primarily descriptive, making theoretical and empirical analysis difficult. This article synthesizes concepts and research by the author and others from diverse disciplines to develop the mid-range theoretical model called the Cultural Determinants of Help Seeking (CDHS). The multidimensional construct of culture, which defines the iterative dimensions of ideology, political-economy, practice and the body, is outlined. The notion of cultural models of wellness and illness as cognitive guides for perception, emotion and behavior; as well as the synthesized concept of idioms of wellness and distress, are introduced. Next, the CDHS theory proposes that sign and symptom perception, the interpretation of their meaning and the dynamics of the social distribution of resources, are all shaped by cultural models. Then, the CDHS model is applied to practice using research with Asians. Lastly, implications for research and practice are discussed.

Keywords: Asian Immigrants, Cultural Models, Help Seeking, Cross Cultural Mental Health, Theoretical Models

The analysis and elimination of health disparities has reached the National priority level. Calls for multilevel, multidisciplinary studies that integrate biological, small group and system-level processes are common across the National Institutes of Health (National Institutes of Health, 2000; OBSSR, 2001). Research such as this is challenging because it is difficult to grasp the mechanisms by which the phenomenon of culture (which is system-level processes) becomes incorporated into community, family and individual-level patterning of illness experience and help seeking. To further complicate this integration, these multiple levels are examined from different fields of study. One recent initiative has suggested a new field called Clinical Social Science (Kleinman, Eisenberg & Good, 2006), that synthesizes and translates social science concepts into clinical strategies with direct application in practice and teaching. Until that time, nursing science can synthesize developed concepts from diverse literatures, identify their linkages, and assemble them into theory that can guide research and practice in health care.

In this article, theoretical concepts are synthesized from divergent disciplines to formulate the Cultural Determinants of Help Seeking (CDHS) theoretical model. Help seeking is an appropriate outcome variable for this mid-range theory because the adoption of health promotion strategies and the effective and satisfying use of health care services by culturally-diverse peoples are critical to reducing and eliminating health disparities. The theoretical model proposed in this article explores the cultural determinants of help seeking to maintain wellness and relieve distress. The model does not attempt to include the structural barriers that affect access to care for diverse cultural groups, such as poverty, social class or education. This is an extremely important research focus, and readers interested in these are urged to examine literature in medical sociology and critical medical anthropology, both lines of inquiry that operationalize race, gender, social class and culture from a political and economical vantage point. Culture in this paper is understood to be a system-level, multidimensional construct that describes the social processes of beliefs and values, rules about social behavior, and social practice.

Background

Culture affects all aspects of health and illness, including the perception of it, the explanations for it, and the behavioral options to promote health or relieve suffering. Anthropologists and transcultural nurses have demonstrated that people from all cultural groups seek help for their suffering based on the meaning that culture assigns to the suffering. Medical anthropology has used the phrase “idioms of distress” to describe the culturally specific experience of psychosocial and physical suffering. However, nursing is also interested in health promotion activities; our interests extend equally to those processes by which people experience health, understand the sources of it, and act to optimize or promote it for themselves and others. Therefore, in this theory, the concept of idioms of distress is expanded into the concept of “idioms of wellness or distress.” An idiom of wellness or distress is a collection of physical, emotional and interpersonal sensations and experiences labeled by the individual as optimal or abnormal, and identified as important. Using this new concept allows for the recognition of culturally distinct patterns of health promotion, wellness and illness experience, meaning interpretation and help seeking, avoiding the premature and/or possibly erroneous conclusion that specific signs of wellness and symptoms of distress or illness are identified and interpreted the same way across cultures. Help seeking in this theory is defined as attempts to maximize wellness or to ameliorate, mitigate, or eliminate distress.

Understanding the ways that people experience and respond to wellness and distress has been a challenging endeavor. Defining the theoretical underpinnings of this theory have involved a journey to study diverse bodies of literature including philosophy, social psychology, medical and psychological anthropology, and transcultural psychiatry and nursing. Each body of work has strengths and limitations. However, this search for culturally relevant practice guidelines has revealed that there has been little integration of social science theories into practice models. This CDHS theory was developed first by examining the literature from these diverse fields to identify concepts that might have practical clinical relevance. Next, these theoretical concepts were synthesized into a model based on their predictive assumptions. In this article, research with the Asian population conducted by the author and others supports these proposed linkages and demonstrates how this theory can guide practice with a given cultural group. However, the author has also made use these concepts for similar analyses with other cultural groups, especially Native Americans and Mexicans. This theory is presented, not as a finished product, but as a stimulus for discussion, elaboration, testing and application.

Conceptual Definitions

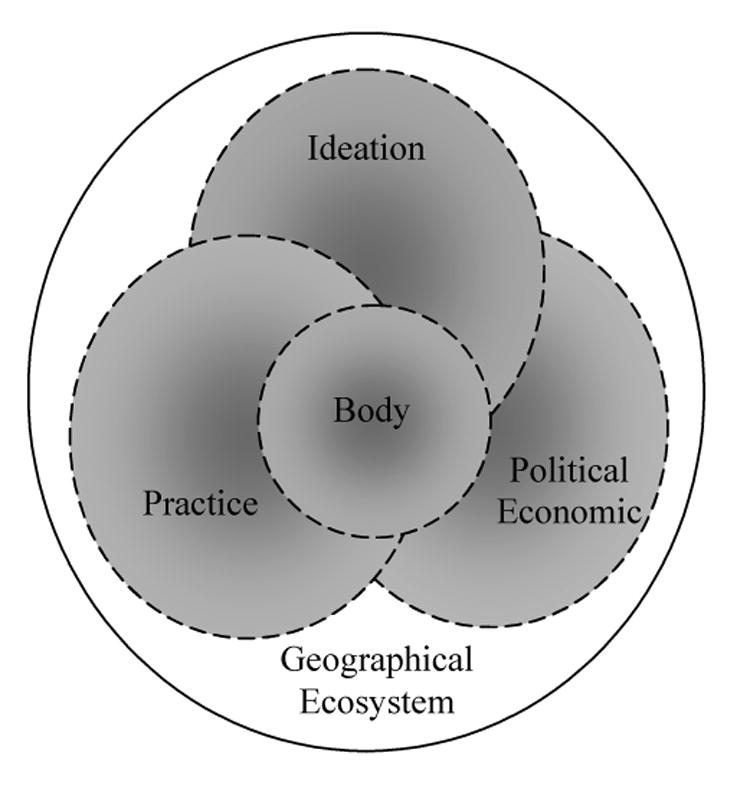

Culture is a set of interacting, system-level, social processes that include four interrelated dimensions (Saint Arnault, 2001) (see Figure 1). Cultural ideology is the beliefs and values held by a people are about what is good, right and normal. The ideology of a culture refers to the available symbols, meanings, and values about what is important and what behaviors are right and correct. Of course, ideologies are about ideals, and are only behavioral guides; the average person rarely achieves these ideals in practice (D'Andrade, 1995; Geertz, 1977; Hodder, 1986; Lutz, 1988; Schneider, 1980; Turner, 1969). Another important and often overlooked element of culture is the political/economic dimension. The political/economic dimension of culture includes the social structures of the society; how families, groups and institutions distribute resources, divide labor, and acquire and distribute wealth. The political/economic dimension of culture also includes how those in power define proper social conduct, as well as how public behavior will be regulated. The political/economic dimension is informed by the cultural ideology, because it is the cultural beliefs and values about “good” and “right” that justify positions about who will hold power over whom (Dirks, Eley & Ortner, 1993; Grimasi, 1992; Harris, 1979; Lindenbaum & Lock, 1993). The final dimension of culture is practice, which includes the traditional behaviors, spatial organization, and interpersonal behaviors. The practice aspect of culture includes both power and ideals—these two forces are acted out in even the smallest gestures, speech patterns, manners of dress, social distances, food choices, and health behaviors. Practice is the embodiment of “tradition.” Thus, cultural practices are the enactments of both cultural ideology and political/economy at the small group or personal level (Berger & Luckmann, 1967; Bourdieu, 1977; Foucault, 1982).

Figure 1.

Overlapping Dimensions of Culture

While the social forces of ideology, political-economy and practice shape belief and behavior, and are enacted by groups and individuals, the body remains crucial in understanding cross-cultural health and illness. As a forth dimension of culture, Scheper-Hughes and Lock (1987) propose that the body is cultural in three important ways: individuals experience the body as the “individual body-self” based on cultural prescriptions and templates; each person experiences themselves as having as a social body, which is a natural symbol for culturally-based thinking about relationships among nature, society and culture; and finally, the body is political, in that it is an artifact of, and is subject to, culturally-based social and political control.

In Figure 1, culture is depicted as mutually iterative dimensions. The body is situated in the middle of the overlapping cultural dimensions, showing how they exert their effects upon the body, and how they are enacted or lived out through the body. Finally, all of these cultural forces occur within, and are shaped, by the geographic ecosystem in which people live, including interacting plants, animals, and physical components such as sunlight, soil, air and water.

The collection of social patterns of interpretation and expectations that are provided for people by their prevailing, local cultural milieu are referred to as cultural models (Holland & Quinn, 1987; Markus, Kitayama & Heiman, 1996; Moscovici, 1988). Cultural models provide specific and consensual guidelines about ideals, values, motivations, goals, social roles and preferred social behaviors. While people may have several cultural models available to guide their perception, thinking, emotions and behavior, unconscious and conscious processes operate that create a coherent cognitive map that is shared by small groups such as families and reference groups. Also, individuals within any given cultural model vary in countless personality dimensions, temperaments, life histories and a host of other variables; future research is needed to illuminate the impact of these personality variables on individual help seeking. In the discussion that follows, the system-level processes of culture relevant to health and help seeking are understood as operationalized at the small-group and individual levels as cultural models of health and illness.

Cultural Determinants of Help Seeking Model

Cultural models direct cognition, emotion and action (Holland & Quinn, 1987; Markus et al., 1996; Moscovici, 1988; Nisbett & Norenzayan, 2002). Perceptions of salient physical or emotional sensations, or relevant aspects of the social environment, are encouraged in individuals in early infancy through the processes of enculturation. The cultural model “tells” the person to attend to certain aspects of his or her experience, what to ignore, what things mean and what should be done about them. Understanding how a given cultural model might direct attention is a starting point for making predictions about how the sensations within the body, emotions and social situations will be perceived, and therefore how health is maintained, or distress is experienced.

Perception and labeling

Studies about how people experience, interpret and label internal sensations and their environment have been conducted within a number of interrelated fields. Ethnobiology is the study of how people of any cultural tradition interpret, conceptualize, represent, cope with, utilize, and generally manage their knowledge of their environmental experience (Ellen, 2006). Interpretative medical anthropology focuses on metaphorical conceptions of the body and shows the social, political, and individual uses to which these conceptions are applied (Waldstein and Adams, 2006). Ethnophysiological theory proposes that, once a sensation is noticed, individuals evaluate them in terms of their normalcy and severity (Hinton and Hinton, 2002).

In short, the attention people give to any given physical or emotional sensation is “filtered through” cultural models. To provide a more complete understanding, cultural models provide a complex set of templates for arousal, attention, and expectation. Cultural models guide attentional amplification of physiological shifts. A person exists as an experiential agent of the cultural model, such that processes of sensation amplification alter their perception and awareness of arousal sensations; this amplification and elaboration are affected by numerous variables, including local ethnophysiology, cultural metaphor, and culturally-based cognitive templates. These, in turn, affect self-surveillance, sensation amplification, and experience labeling (Hinton and Hinton, 2002). For example, some cultures have a rich and varied understanding of subtle changes in the body, such as skin sensitivity, digestive patterns, and tongue characteristics; other cultures have less sophisticated attention to the body, but have a rich and varied emotional awareness.

The CDHS theory proposes that physical or emotional sensations are labeled “signs of wellness” when they are interpreted as desired, valued, ideal or optimal states. Physical sensations or emotions are labeled “symptoms” when they are interpreted as a sign of an abnormal state, a disturbance, pathology or an illness. Along with labeling, individuals and groups evaluate the level of importance or severity of the sign or symptom. Often signs and symptoms are experienced as a collection, constellation or cluster (Kirmayer, 2001).

Interpretations of Meaning

Once wellness signs or distress symptoms are experienced and labeled, people consider the meanings of what they have noticed in terms of what the cultural model “tells” them might have caused the signs or symptoms. People also consider what this means about them as a person based on the ideals of the culture, and about themselves as a member of the group.

Causal attributions

Cultural models influence shared conceptualizations about the body, the nature of the healthy self, and what symptoms signify a condition outside the range of normal. In addition, cultural models provide explanations about the cause of wellness and distress, referred to as explanatory models (Kleinman, 1988, 1995). Explanatory models provide culturally-specific explanations about how health and wellness are achieved, as well as the causes of distress and illness. In addition, explanatory models allow groups to develop shared and meaningful patterns of health promotion, need and care that are natural and predictable within the larger cultural model.

Individuals make three types of interpretations of causes of signs or symptom clusters that affect help seeking (Kirmayer, Dao and Smith, 1998). A somatic interpretation is the attribution of a physical sources of wellness or distress; a psychological interpretation is about emotional sources; and an environmental interpretation posits social or physical environment sources (Robbins and Kirmayer, 2001). In general, we can predict that people will attempt to match their help seeking behavior to their interpretations about the sources of wellness or causes of distress (Chrisman & Kleinman, 1993).

Social significance

Individuals also make estimations about the positive or negative social significance of their signs of wellness and distress symptoms based on cultural models (Kleinman and Good, 1986; Corrigan, 2005). Signs of wellness may be positively evaluated and may be a source of pride because they are evaluated as meaning that the person is good, or happy, or in some way, socially desirable. Wellness may be interpreted as an indication that one has achieved individual, group or social goals. Symptoms of distress or illness can be interpreted as indicating signs of moral weakness, physical frailty, or failure to carry out important social roles. Illnesses may be evaluated negatively when they signify that a person (or a family member) has failed in some important social role. When people evaluate their distress or illness as negative, they will have emotional responses of shame, humiliation, anxiety or fear. These people will avoid disclosing it out of fear of the social consequences.

Social Context Dynamics

The interpretation of the meaning of an experience of wellness or distress occurs within an individual with reference to the cultural model. However, help seeking requires the engagement of the social network. These networks include relationships of power that operate to exchange social resources, including division of the labor of care and support. Cultural models differ in terms of whether they emphasize the group or the individual. Therefore, the next step in the help seeking process involves an analysis of the rules that regulate resource exchange.

Availability of resources

The emphasis of a cultural model on the group or the individual can greatly impact the availability of social resources (Bruner, 1991; Fiske, Kitayama, Markus & Nisbett, 1998; Geertz, 1993; Lawson & McCauley, 1990; Markus, Mullally & Kitayama, 1997; Shweder, 1991). Within a group-oriented system, there is a cultural emphasis on behaviors that foster group harmony and solidarity. Within a group-oriented cultural model, the focus is on the family as the primary vehicle of support and nurturance of the individual. Resources are understood to be available to group members for the benefit of the group as a whole. In a group-oriented model, health is considered the result of, and a resource of, the well-functioning group, rather than a solely an individual asset. Also, illness can be seen as the result of a poorly functioning group, and a detriment to the group as a whole.

Individually-oriented cultural models have a cultural emphasis on the needs, feelings and attributes of the individual. Within these individually-oriented cultural models, the focus is on the individual as an agent of his or her own circumstances. Resources are distributed by the group to the individual, and while gratitude is expected, the resource is primarily for the benefit of the individual, thereby promoting his or her success. Wellness in an individually-oriented cultural model is an individual achievement based on moral character, daily habits or personal success. Alternately, while illness affects others, it is primarily an individual failure. The responsibility for health falls upon the individual.

Exchange rules

Cultural models also include guidelines about the exchange of support and help within the perceived social resources. Reciprocity refers to expectations about the give and take of instrumental, social and emotional support, and rules about who should engage in these exchanges, and under what circumstances. Because group-oriented cultural models believe that health and illness arise from, and are the responsibility of, the group, they may expect their members to seek help only from known, intimate or in-group members. These cultural models also have edicts that each favor incurs a reciprocal exchange, but that reciprocity may be repaid to other people within the in-group. In addition, some group-oriented cultural models have specific rules about the situations in which reciprocity between people who are not members of the same family or in-group is appropriate, and what the exchange should be (Backnik, 1994; Hendry, 1992; Saint Arnault, 1998, 2002, 2004). Experiences of wellness are a group-level asset that may be seen as a situational factor that can be considered when reciprocity is expected. For example, someone old, frail or ill who needs help might not be expected to repay based on social exchange rules. Rather, other members of the group, who are healthy, are responsible to repay those favors.

Individually-oriented cultural models foster individual autonomy, and have contractual exchange rules, in which autonomous individual agents repay debts in-kind within a proximate span of time. These individually-oriented cultural models may expect that people will only ask for assistance when they cannot do for themselves and will repay the favor within a short time frame (Antonucci, 1990; Gouldner, 1960; Klein Ikkink, 1999; Neufeld & Harrison, 1995; Rusbult, 1993). The expectation for repayment might be suspended or lifted until the individual regains health and strength.

Model Description

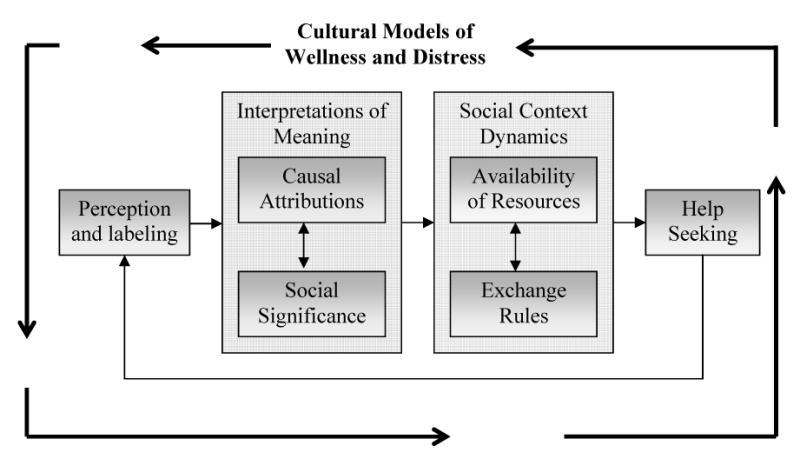

In summary, the CDHS model (figure 2) proposes that the processes of perception, meaning interpretation, as well as resource exchange, are filtered through cultural models of wellness and distress. The help seeking process begins when there is a perception of physical or emotional sensations. In the model, wellness or distress perceptions are identified and labeled as important, optimal or abnormal, beginning of a series of interpretations and evaluations used by people to determine if (and what) additional help is needed (perception and labeling).

Figure 2.

Cultural Determinants of Help Seeking Model

Once wellness signs or distress symptoms are experienced and labeled, people interpret the meaning of them. When a person deems the wellness signs or distress symptoms to be significant, the person then determines what the possible source or cause might be (causal attribution). Sometimes individuals may determine that their experiences are caused by their ways of thinking, and reinforce them or institute internal adjustments to eliminate them. Alternatively, individuals may interpret their wellness or distress to be caused by personal habits or behaviors. In this case, people will try to strengthen them to maintain or support their wellness, or alter daily habits to try to eliminate symptoms. The causes for these signs or symptoms are related to the interpretation of the social significance (social significance). People may decide that their wellness is a sign that they are living the good life, are moral and right, and believe that they can be examples to others. Sometimes people may decide that their symptoms suggest that they have committed a social failure, and choose to hide them. A person may decide that their condition is not amenable to help, or that it is simply too shameful to acknowledge their needs.

After this interpretation of the cause and social significance of wellness signs or distress symptoms, people begin evaluating the rules that govern the resources available within their social network. The person may be in a social network that sees wellness as a group asset and may therefore expect that resource to be shared for the benefit of all members. Others may be in a social network in which wellness represents a personal achievement (availability of resources).

Next, the social network has rules about the exchange of the resources they posses. People assess their relationships to determine who will support their wellness, or from whom they can ask for help; determining what type of help they can request, and at what cost (reciprocity rules). They consider the forms and strategies they should use to access support. They may find that closeness and supports regarding their distress are unavailable, or decide that asking for help creates too many social complications, deciding to keep quiet. When people suffer from symptoms that they have deemed to be of negative social significance, social rules may dictate that they can only share those feelings with people who are in a reciprocal helping relationship with them, such as immediate or extended family. Other cultures prohibit burdening ones family with problems and prescribe that one should seek a paid professional for troubles and needs, leaving the family as the place where good feelings are shared.

CDHS Theory and Practice with Asians

For over 20 years, the health care community has struggled to respond to the mandate for cultural sensitivity in their provision of care. Mastery of all of the relevant cultural variants demonstrated by a diverse population makes this task overwhelming for busy practitioners. This CDHS is one response to this need, providing health care providers the assessment categories that they can use regardless of the cultural group, and by providing suggestions about how these might operate to affect help seeking. Most practices are based in communities with established cultural groups. Using these assessment categories, health care providers can begin to discover themes within commonly contacted groups, and develop strategies to address them. Therefore, it is helpful to look at research data from one group to demonstrate how the CDHS can be used to understand the relationships among the theoretical concepts and the implications of these for practice. It should be clear, however, that these cultural concepts and processes could be used to analyze any cultural group.

Of course, most clinical cultural research focuses on distress and illness. However, assessment of symptoms of distress requires understanding of what conceptions of normalcy and health are for that group. In general, people enculturated within many Asian countries share the belief that health is part of a holistic system of experience in which the spiritual realm (including ancestors and gods), society, the body, thinking activities and emotions are intertwined. In a system such as this, experiences of health are understood to be the result of a person who has respectful and appropriate relationships with the spirits, with others, especially those in ones family, whose diet is appropriate for the season and ones constitution, and whose thoughts and emotions are balanced and harmonious. In this system, physical sensations are closely monitored because they are understood as signs of emerging disharmony in one of more of these areas. For many Asians, attending to disharmony and restoration of harmony or balance is the key to health. Therefore, attention to subtle physical sensations, diet patterns, sleep patterns, social rules and spiritual activities are attended to daily (Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations, 1995; Kleinman, 1982, 1983, 1988; Lock, 1987; Ohnuki-Tierney, 1984; Sue, 1999).

Somatic symptoms in Asians

Complaints of physical symptoms can be seen in any population; however Asian groups from many countries describe their distress in somatic forms (Draguns, Phillips, Broverman & Caudill, 1970; Gureje, Simon, Ustun & Goldberg, 1997; Hinton & Hinton, 2002; Hong, Lee & Lorenzo, 1995; N. Iwata & Roberts, 1996; Kanno, 1981; Kawanishi, 1992; Kirmayer, Dao & Smith, 1998; Kirmayer & Groleau, 2001; Lock, 1987a; Maeno et al., 2002; Pang, 1998; Parsons & Wakeley, 1991; Simon et al., 1999). In Japanese clinics, 13% to 15% of patients had both depression and co-occurring physical symptoms (Maeno et al., 2002; Mino, Aoyama & Froom, 1994).

Ethnographic and ethnophysiological studies have explored this somatic distress in Asians in more detail. In a review of interactions between Chinese physicians and their patients, Ots found that both physicians and patients related internal organs with emotions, and carefully examined bodily perceptions (Ots, 1990). For example, the liver was believed to be the cause of headaches, epigastric pain, hypertension and anger, while the heart was thought to cause anxiety, uncertainty and fear. In a sample of Koreans with depression, Pang found that people connected internal organs, emotions and bodily sensations. These patients described depression as a symptom cluster that included anger, physical pain and social discord (Pang, 1998). Finally, Lock (1987b) explains that futeishūso (non-specific physical complaints) includes symptoms such as coldness, shoulder pain, palpitations and nervousness. Both the physicians and patients in her study related these symptoms with social discontent, problems with the autonomic nervous system, pelvic inflammatory disease, and general personality sensitivity.

Saint Arnault, Sakamoto and Moriwaki (2006) tested whether the symptoms found in ethnographic studies might be seen in a larger sample of 50 female Japanese college students using standardized measures. Using a broad physical symptom inventory (Pennebaker, 1982), as well as a Japanese version of the Beck Depression Inventory, the authors found that the Japanese women who scored above 15 on the Beck had significantly higher mean scores for the neurological (weakness, faintness, dizziness, lightheadedness, numbness), gastrointestinal (abdominal pain, stomachache, abdominal cramps), neuromuscular (pain in the shoulders, stiff joints), and cardiac symptoms (inability to breathe, and palpitations) (p < .03) than their non-depressed counterparts (Saint Arnault, Sakamoto & Moriwaki, 2006). They also found that the Japanese had higher somatic distress means than Americans, which they interpreted this finding as related to a culturally-patterned perceptual focus on the body rather than a difference in levels of distress.

Causal Interpretation as Social and Environmental

As stated above, many people enculturated in Asian cultures tend to have a holistic view of the body as in balance with natural, social and spiritual forces. Experiences of wellness are believed to be caused by this harmonious integration. Research has shown that Asians may attribute their somatic experiences, whether wellness or distress, to environmental and somatic causes. In situations of distress, this causal attribution may explain the tendency for Asians to primarily use medical care and social support (Guarnaccia, Rivera, Franco & Neighbors, 1996; Hinton, Um & Ba, 2001; Jenkins, Kleinman & Good, 1991; Kirmayer, 1993; Kirmayer et al., 1998; Kirmayer & Young, 1999; Kleinman, 1988, 1996, 2003; Pang, 1998).

The Symptom Interpretation Questionnaire (Robbins & Kirmayer, 1991) measures whether people attribute commonly occurring physical symptoms to somatic, psychological, or environmental causes. There have been very few studies that examine the relationship between symptom interpretation and service use. An example of such a study was conducted by Parker & Parker (2003), examined symptom interpretation and use of mental health services for 698 patients in Sydney, Australia. They found that psychological interpretation for somatic symptoms was related to both a history of depression and use of mental health services (unfortunately, ethnicity was not reported). However, we do not know whether those Asians who seek help from primary care clinics are more likely to hold physical interpretations about their distress, while those who do not use such services believe that their distress is somatic or environmental. This is a challenging area for nursing research.

Social Evaluation as Shameful

Research about Asian philosophy has shown that people from many Asians countries share Confucian collectivist values. These values foster a focus on the in-group, especially ones family. In a philosophical system such as this, wellness is attributed to fulfillment of ones social roles, the existence of mutually supportive relationships within the family, as well as proper respect and conduct with ancestors.

Research has suggested that these shared beliefs also cast shame onto the families of those who experience mental illness because the experience of distress signifies a lack of a supportive network, inability to fulfill social roles or improper relationships with family or ancestors (Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations, 1995; Iwamasa & Hilliard, 1999; Lin & Cheung, 1999; Ma, 1999). While this negative evaluation is assumed to inhibit the use of mental health care, very few studies have examined specifically how this relates to cultural models. One effort to systematize the assessment of the social evaluation of distress is the development of the Beliefs toward Mental Illness Scale (BMI) (Hirai & Clum, 2000). These authors operationalize the socially significant cultural beliefs about mental illness to be beliefs about dangerousness, incurability and poor social skills. For one Asian sample, high scores for beliefs about dangerousness were positively correlated with seeking medical care instead of psychological care; high scores for beliefs about incurability were negatively correlated with seeking medical care; and scores for beliefs about poor social skills were positively correlated with use of folk medicine (Hirai & Clum, 2000). Furthermore, while many studies have made assumptions about how the social evaluation of distress affects help seeking, no published studies have documented the relationship between symptom perceptions, interpretation, resource-related social dynamics, and help seeking.

Perception of Social Resources: In-group and Hierarchical Social Networks

As noted earlier, a core aspect of the Confucian philosophy is the prescriptions about the nature of interpersonal relationships, especially the belief that the individual's primary or ideal concern is with their family (Kim, Atkinson & Yang, 1999; Rozman, 1991; Sue, 1999). Confucian philosophy also specifically structures society along hierarchal-status lines. Within this social system, the individual knows that smooth functioning within the group requires sensitively to one's role within the group. For these Asian cultures, the primary social unit is the family and the primary reference group. A reference group is the group that the person feels identification with, and may include a peer group or ones co-workers. Wellness signifies that an Asian person is engaged in mutually interdependent relationships with the people in their primary reference group and their family, sharing responsibility for the support and security with all of the other members. A well person understands and respects their obligations both to family, and to the harmony within his or her primary reference group. Research has shown that many Japanese favor reliance on the primary family or group for emotional support (Fetters, 1998) and that they simultaneously fear stigmatizing or shaming the family if they use professional mental health care (Alem et al., 1999; Atkinson & Gim, 1989; Bekker, Hentschel & Fujita, 1996; Flum, 1998; Hom, 1998; Kagawa-Singer, Wellisch & Durvasula, 1997; Kim, 1998; W. Kim, 2003; Narikiyo & Kameoka, 1992; Ono et al., 2001; Suan & Tyler, 1990; Yeh, Inose, Kobori & Chang, 2001).

One effort to measure ideas about ones relations is the Asian Values Scale (Kim, Atkinson and Yang, 1999). Studies that examine adherence to Asian values find that high adherence is negatively associated with the actual use of counseling. In general, research has found that low levels of acculturation, however it is defined, is related to a tendency not to use psychological services (Atkinson & Gim, 1989; Hom, 1998; H. H. W. Kim, 1998; Le, 1996; Lee, 2002; Schwartz, 1998; Zhang & Dixon, 2003)

Social exchange rules and norms

Above, research was presented that illuminated the relationship between some Asian values and the social resources relevant to health and distress. In addition to these interpretations, these cultural values also relate to rules regarding social exchange of those resources. The values described above foster group harmony by encouraging social exchange within the family and the primary reference group. A well person is one who understands and engages in this mutual exchange of resources. Autonomy is fostered in the sense that one cares for ones own needs to avoid over tapping these limited reserves. Therefore, a well person is one who handles their own needs and who works with others to benefit the strength and capabilities of everyone in the group.

In contrast, within that same system, group harmony rules may also discourage the open display of emotions, and may sanction the expression of negative emotion because they may disrupt the harmony and solidarity of the group. Research has also shown that Asians may deny the experience and expression of emotions, or may conform to social emotion display rules that favor showing somatic rather than emotional or interpersonal distress (Kirmayer, 2001; Kleinman, 1982, 1983, 1988; Lin, 1996; Lock, 1987; Ohnuki-Tierney, 1984).

The social structure described above serves to modify and inhibit support-giving and help seeking. A reciprocity norm for the Japanese is to ask for help only within one's intimate social group (Backnik, 1994; Hendry, 1992; Saint Arnault, 1998, 2002, 2004). Therefore, people need to be self-reliant to avoid overtaxing limited support reserves. Appropriate role behavior includes indirect communication of personal needs, and limited negative and positive emotional expression outside of ones intimate social circle. Behaviors that foster conflict or indicate deviance are frowned upon, and may result in ostracism (Bestor, 1996; Johnson, 1995; Lebra, 1976; Saint Arnault, 1998, 2002; Smith, 1961). Very little research has been done to examine the effects of reciprocity rules on help seeking (See Klein Ikkink, 1999; Neufeld & Harrison, 1995; and Rusbult, 1993 for examples of such work on care giving and receiving). However, Saint Arnault found that Japanese expatriate spouses felt unable to freely express emotional distress within their general social network, as well as cultural rules dictating reciprocity in the exchange of social support (Saint Arnault, 2002).

Implications for Research and Practice

The CDHS model has implications for cross-cultural health promotion, primary health care and psychiatry. First, the model illustrates how and why we must integrate ethnographic, epidemiological, survey and clinical methods and data to understand these complex cultural questions. One example seen here is the need for identification of culturally relevant symptom sets in large groups. Perhaps we can discover symptom clusters in large populations that can improve the sensitivity of our assessments, thereby increasing the accuracy of our community-based screening efforts. Improved assessments will also lead to more appropriate referrals and interventions for our culturally diverse clients. In order to do this, we must move systematically between the small-scale interviews common in ethnophysiological research toward the use of surveys that can examine these in wider populations, enabling us to compare symptom sets across cultural groups. These surveys, however, must be based on the logic of cultural system in question, instead of using the western cultural system as a norm.

Second, understanding the interaction among culturally based intra- and inter-personal factors may help researchers and practitioners target their efforts toward the forces that inhibit help seeking. General notions about stigma and language issues in health care utilization have yielded little in the way of removing the interacting obstacles that prevent service utilization, especially in the areas of mental health and other socially significant diseases. We need to identify how symptom perceptions, meaning interpretations and the exchange of social resources interact to fully understand and predict culturally-related help seeking strategies. This detailed knowledge will help service providers identify risk groups and develop culturally relevant services for them.

We have seen that the symptoms that warrant help seeking from a health care professional will not be experienced, understood and/or communicated in the same way across cultural groups. Health care providers must understand the cultural groups that they serve. Most clinics service people from predictable cultural groups. Groundwork outside of clinic time is time well spent when the providers can be conversant in the experiences and interpretations of important symptom sets. In addition, securing the services of cultural translators that can help providers learn more within the clinic setting can also be extremely helpful. A cultural translator is someone who understands and can articulate the dominant idioms of wellness and distress of their cultural group. Often, volunteers from communities can serve in this capacity. However, the cultural model presented here also illustrates how understandings and social evaluations will vary by gender, class and religion, so that the careful choice of cultural translators is essential.

The symptom sets used in American and international assessments to evaluate distress have relied on somatic indicators such as sleep, appetite and fatigue, which may have been based on the idioms of distress for western samples. As we have seen, focusing on these symptoms may be systematically overlooking symptoms that may be important for members of other groups—symptoms such as headache, neurological symptoms, muscular and joint pain and abdominal distress. The construct validity of western derived notion that the important emotions in depression are exclusively happiness, sadness, hopeless and guilt are vigorously critiqued in both Native American and Asian studies (See Iwata & Buka, 2002, Iwata, Roberts & Norito, 1995 and Manson & Kleinman, 1998 for examples of this critique).

The nature of culture lends itself to multidisciplinary and mixed-method research strategies. Only by working across disciplinary lines can we succeed in creating synthesized theories that can guide practice. As we have seen, while culture is a system-level phenomenon, it becomes part of an individual's cognition, and is therefore enacted at the small group and individual levels. Culture necessarily affects health and distress perceptions, interpretation, communication and social support, and ultimately all help seeking behaviors. Within each of these domains, one can use qualitative and quantitative methods to document mechanisms and explicate dynamics (Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, 2001). Readers are encouraged to take up this challenge to deepen our nursing research about the complexity of culture and help seeking.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research and the National Institute of Mental Health MH071307).

References

- Alem A, Jacobsson L, Araya M, Kebede D, Kullgren G. How are mental disorders seen and where is help sought in a rural Ethiopian community?: A key informant study in Butajira, Ethiopia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplementum. 1999;100 397:40–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC. Social supports and social relationships. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. New York: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations. Taking action: Improving access to health care for Asians and Pacific Islanders. Oakland, CA: Author; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson DR, Gim RH. Asian-American cultural identity and attitudes toward mental health services. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1989;36(2):209–212. [Google Scholar]

- Backnik J. Introduction: Uchi/Soto: Challenging our concept of self, social order and language. In: Backnik JM, Quinn C, editors. Situated Meanings: Inside and outside in Japan: Self, society and language. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bekker FJ, Hentschel U, Fujita M. Basic cultural values and differences in attitudes towards health, illness and treatment preferences within a psychosomatic frame of reference. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics. 1996;65(4):191–198. doi: 10.1159/000289074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger P, Luckmann T. The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. New York: Doubleday; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Outline of a theory of practice. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung F. Conceptualization of psychiatric illness and help-seeking behavior among Chinese. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 1987;11(1):97–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00055011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrisman N, Kleinman A. Popular health care, social networks and cultural meaning: the orientation of medical anthropology. In: Mechanic D, editor. Handbook of health, health care and the health professionals. NY: The Free Press; 1993. pp. 569–590. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. On stigma and mental illness: Practical strategies for research and social change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrade R. The development of cognitive anthropology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dirks N, Eley G, Ortner S. Culture/Power/History: A reader in contemporary social theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Draguns JG, Phillips L, Broverman IK, Caudill W. Social competence and psychiatric symptomatology in Japan: A cross-cultural extension of earlier American findings. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1970;75(1):68–73. doi: 10.1037/h0028787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner J. The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry. 1991;18(121) [Google Scholar]

- Ellen R. Introduction. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 2006;12(s1):siii–s22. [Google Scholar]

- Fetters M. Cultural Clashes: Japanese patients and U.S. maternity care. Japanese International Institute, Winter. 1997;17 [Google Scholar]

- Fetters MD. The family in medical decision-making: Japanese perspectives. Journal of Clinical Ethics. 1998;9(2):132–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske AP, Kitayama S, Markus HR, Nisbett RE. The cultural matrix of social psychology. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4. Vol. 2. Boston, MA: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 915–981. [Google Scholar]

- Flum ME. Attitudes toward mental health and help-seeking preferences of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean international college students. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities & Social Sciences. 1998;59(5A):1470. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. The archeology of knowledge. New York: Pantheon Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. Religion as a cultural system. In: Geertz C, editor. The interpretation of cultures: selected essays. Fontana Press; 1993. pp. 87–125. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. The interpretation of culture. New York: Basic Books; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner AW. The norms of reciprocity: a preliminary statement. American Sociological Review. 1960;25:161–179. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein B, Rosselli F. Etiological paradigms of depression: The relationship between perceived causes, empowerment, treatment preferences, and stigma. Journal of Mental Health. 2003;12(6):551–563. [Google Scholar]

- Grimasi A. Prison notebooks. New York: Columbia University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaccia PJ, Rivera M, Franco F, Neighbors C. The experiences of Ataques de Nervios: Towards an anthropology of emotions in Puerto Rico. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 1996;20(3):343–367. doi: 10.1007/BF00113824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O, Simon GE, Ustun TB, Goldberg DP. Somatization in cross-cultural perspective: A World Health Organization study in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154(7):989–995. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M. Cultural Materialism: The struggle for a science of culture. New York: Random House Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hendry J. Individualism and individuation: entry into a social world. In: Goodman R, Refsing K, editors. Ideology and practice in modern Japan. NY: Routledge; 1992. pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton D, Hinton S. Panic disorder, somatization, and the new cross-cultural psychiatry: the seven bodies of a medical anthropology of panic. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 2002;26(2):155–178. doi: 10.1023/a:1016374801153. [comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton D, Um K, Ba P. A unique panic-disorder presentation among Khmer refugees: the sore-neck syndrome. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 2001;25(3):297–316. doi: 10.1023/a:1011848808980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai M, Clum G. Development, reliability, and validity of the Beliefs toward Mental Illness Scale. Journal of psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2000;22(3):221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder I. Reading the past: Current approaches to interpretation in archeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Holland D, Quinn N, editors. Cultural models in language and thought. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hom KL. Investigating the influence of individualism-collectivism and acculturation on counselor preference and attitudes toward seeking counseling among Asian-Americans. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering. 1998;58(8B):4451. [Google Scholar]

- Hong GK, Lee BS, Lorenzo MK. Somatization in Chinese American clients: Implications for psychotherapeutic services. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 1995;25(2):105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Iwamasa GY, Hilliard KM. Depression and anxiety among Asian American elders: a review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 1999;19(3):343–357. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N, Buka S. Race/ethnicity and depressive symptoms: A cross-cultural/ethnic comparison among university students in East Asia, North and South America. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55(12):2243–2252. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N, Roberts C, Norito K. Japan-US comparison of responses to depression scale items among adult workers. Psychiatry Research. 1995;58:237–245. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02734-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N, Roberts R. Age differences among Japanese on the Center for Epidiologic Studies Depression scale: An Ethnocultural perspective on somatization. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;43(6):967–974. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JH, Kleinman A, Good BJ. Cross-cultural studies of depression. In: Becker J, Kleinman A, editors. Psychosocial aspects of depression. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1991. pp. 67–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa-Singer M, Wellisch D, Durvasula R. Impact of breast cancer on Asian women and Anglo American women. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 1997;21:449–480. doi: 10.1023/a:1005314602587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno S. On the somatization of symptom in psychosomatic disease: consideration of Rorschach score (author's transl) Shinrigaku kenkyu: The Japanese Journal of Psychology. 1981;52(1):30–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawanishi Y. Somatization of Asians: An artifact of Western Medicalization. Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review. 1992;29:5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Atkinson DR, Yang PH. The Asian Values Scale: Development, factor analysis, validation, and reliability. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46(3):342–352. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HHW. Asian-American students: Ethnicity, acculturation, type of problems and their effect on willingness to seek counseling and comfort level in working with different types of counselors. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities & Social Sciences. 1998;58(9A):3417. [Google Scholar]

- Kim W. Ethnic variations in mental health symptoms and functioning among Asian Americans. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities & Social Sciences. 2003;63(8A):3004. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ. Culture and psychiatric epidemiology in Japanese primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1993;15(4):219–223. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(93)90036-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ. Cultural variations in the clinical presentation of depression and anxiety: Implications for diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62 13:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Dao T, Smith A. Somatization and psychologization: Understanding cultural idioms of distress. In: Okpaku S, editor. Clinical methods in transcultural psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1998. pp. 233–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Groleau D. Affective disorders in cultural context. Psychiatric Clinics of North America Special Issue: Cultural psychiatry: International perspectives. 2001;24(3):465–478. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Young A. Culture and context in the evolutionary concept of mental disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108(3):446–452. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.3.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein Ikkink KK, van Tilberg T. Broken ties: reciprocity and other factors affecting the termination of older adult's relationships. Social Networks. 1999;21:131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Neurasthenia and depression: A study of somatization and culture in China. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 1982;6(2):117–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00051427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. The cultural meanings and social uses of illness: A role for medical anthropology and clinically oriented social science in the development of primary care theory and research. Journal of Family Practice. 1983;16(3):539–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Rethinking psychiatry: From cultural category to personal experience. New York, NY: Free Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Do psychiatric disorders differ in different cultures? The methodological questions. In: Kleinman A, editor. The culture and psychology reader. New York, NY: New York University Press; 1995. pp. 631–651. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. How is culture important for DSM-IV? In: Mezzich JE, Kleinman A, Fabrega H, Parron DL, editors. Culture and psychiatric diagnosis: A DSM-IV perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1996. pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Introduction: Common mental disorders, primary care, and the global mental health research agenda. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2003;11(3) doi: 10.1080/10673220303953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good BJ. Culture, illness, and care: Clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Focus. 2006;4(1):140. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-2-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A, Good BJ. Culture and Depression. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson ET, McCauley R. Rethinking Religion: Connecting Cognition and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Le M. Factors affecting the help-seeking preference of Asian-American college students experiencing depressive symptoms. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering. 1996;57(4B):2872. [Google Scholar]

- Lee DY. The influence of acculturation and racial identity upon Asian Americans' attitudes toward seeking psychological help. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering. 2002;63(5B):2591. [Google Scholar]

- Lin K. Asian American perspectives. In: Mezzich JE, Kleinman A, editors. Culture and psychiatric diagnosis: A DSM-IV perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1996. pp. 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lin K, Cheung F. Mental health issues for Asian Americans. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:774–780. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.6.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenbaum S, Lock M. Knowledge, power, and practice: the anthropology of medicine and everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lock M. Introduction: Health and medical care as cultural and social phenomena. In: Norbeck E, Lock M, editors. Health, illness, and medical care in Japan: Cultural and social dimensions. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press; 1987a. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lock M. Protests of a good wife and wise mother: The medicalization of distress in Japan. In: Norbeck E, Lock M, editors. Health, illness, and medical care in Japan: Cultural and social dimensions. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press; 1987b. pp. 130–157. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz C. Universal emotions: Every day sentiments on a Micronesian atoll and their challenge to western theory. Chicago: Chicago University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ma G. Access to health care for Asian Americans. In: Ma G, Henderson G, editors. Ethnicity and Health care: A socio-cultural approach. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1999. pp. 99–121. [Google Scholar]

- Maeno T, Kizawa Y, Ueno Y, Nakata Y, Sato T. Depression among primary care patients with complaints of headache and general fatigue. Primary Care Psychiatry. 2002;8(2):69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM, Kleinman A. DSM-IV, culture and mood disorders: A critical reflection on recent progress. Transcultural Psychiatry. 1998;35(3):377–386. [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, Mullally P, Kitayama S. Selfways: Diversity in modes of cultural participation. In: Neisser U, Jopling DA, editors. The conceptual self in context: Culture, experience, self-understanding. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 13–61. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S, Heiman RJ. Culture and “basic” psychological principles. In: Higgins E, Kruglanski A, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 857–913. [Google Scholar]

- Mino Y, Aoyama H, Froom J. Depressive disorders in Japanese primary care patients. Family Practice. 1994;11(4):363–367. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovici S. Notes towards a description of social representations. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1988;18(3):211–250. [Google Scholar]

- Narikiyo TA, Kameoka VA. Attributions of mental illness and judgments about help seeking among Japanese-American and White American students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1992;39(3):363–369. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. Strategic research plan to reduce and ultimately eliminate health disparities: fiscal year 2002-2006. 2000 Retrieved June 1, 2007 from http://obssr.od.nih.gov/Content/Strategic_Planning/Health_Disparities/HealthDisp.htm.

- Neufeld A, Harrison MJ. Reciprocity and social support in caregivers' relationships: variations and consequences. Qualitative Health Research. 1995;5:348–365. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett RE, Norenzayan A. Culture and cognition. In: Pashler H, Medin D, editors. Steven's handbook of experimental psychology. 3. 2: Memory and cognitive processes. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2002. pp. 561–597. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. Progress and Promise in Research on Social and Cultural Dimensions of Health: A Research Agenda. 2001 Retreived June 1, 2007 from http://obssr.od.nih.gov/Documents/Conferences_And_Workshops/HigherLevels_Final.PDF.

- Ohnuki-Tierney E. Illness and culture in contemporary Japan: An anthropological view. London: Cambridge University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ono Y, Tanaka E, Oyama H, Toyokawa K, Koizumi T, Shinohe K, et al. Epidemiology of suicidal ideation and help-seeking behaviors among the elderly in Japan. Psychiatry & Clinical Neurosciences. 2001;55(6):605–610. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2001.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ots T. The angry liver, the anxious heart and the melancholy spleen: The phenomenology of perceptions in Chinese culture. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 1990;14(1):21–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00046703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang KYC. Symptoms of depression in elderly Korean immigrants: Narration and the healing process. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 1998;22(1):93–122. doi: 10.1023/a:1005389321714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons CD, Wakeley P. Idioms of distress: Somatic responses to distress in everyday life. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 1991;15(1):111–132. doi: 10.1007/BF00050830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. The psychology of physical symptoms. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins J, Kirmayer L. Attributions of common somatic symptoms. Psychological Medicine. 1991;21:1029–1045. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozman G. The East Asian Region: Confucian Heritage and Its Modern Adaptation. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Bunk AP. Commitment processes in close relationships: an interdependence analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1993;10:175–204. [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault D. Unpublished Dissertation. Wayne State University; Detroit: 1998. Japanese Company Wives living in America: Culture, social relationships, and self. [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault D. Help seeking and social support in Japanese company wives. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2002;24(3):295–306. doi: 10.1177/01939450222045914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault D. The Japanese. In: Ember M, Ember C, editors. The encyclopedia of medical anthropology. Vol. 2. Amherst: Yale University; 2004. pp. 765–776. [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault D, Sakamoto S, Moriwaki A. Somatic and Depressive Symptoms in Female Japanese and American Students: A Preliminary Investigation. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2006:275–286. doi: 10.1177/1363461506064867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz PY. Depressive symptomatology and somatic complaints in the acculturation of Chinese immigrants. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering. 1998;59(5B):2434. [Google Scholar]

- Scheper-Hughes N, Lock MM. The mindful body: A prolegomenon to future work in medical anthropology. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1987;1(1):6–41. [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, VonKorff M, Piccinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J. An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341(18):1329–1335. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider D. American kinship: A cultural account. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Shweder RA. Thinking through cultures: Expeditions in cultural psychology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Suan LV, Tyler JD. Mental health values and preference for mental health resources of Japanese-American and Caucasian-American students. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice. 1990;21(4):291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Sue S. Asian American Mental Health. In: Lonner W, Dinnel D, editors. Merging past, present, and future in cross-cultural psychology. Lisse, Netherlands: Swets and Zeitlinger; 1999. pp. 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Turner V. The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Waldstein A, Adams C. The interface between medical anthropology and medical ethnobiology. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 2006;12(s1):s95–s118. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh C, Inose M, Kobori A, Chang T. Self and coping among college students in Japan. Journal of College Student Development. 2001;42(3):242–256. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Dixon DN. Acculturation and Attitudes of Asian International Students Toward Seeking Psychological Help. Journal of Multicultural Counseling & Development. 2003;31(3):205–222. [Google Scholar]