Abstract

To examine young adult smoking patterns, we interviewed 732 smokers (from five U.S. upper Midwestern states) via telephone in 2006. We first defined two groups of intermittent smokers—low (smoked 1–14 days in past 30) and high (smoked 15–29 days in past 30), and then analyzed differences between these two groups and daily smokers. Low intermittent smokers were much less likely than high intermittent smokers to consider themselves smokers, feel addicted, or smoke with friends. Daily smokers were more likely than high intermittent smokers to feel addicted and have trouble quitting. Implications, limitations and ideas for future studies are discussed.

Keywords: young adults, occasional smoking, intermittent smoking, daily smokers, non-daily smoking

Introduction

In recent years, tobacco researchers have given increased attention to a subset of smokers who do not smoke on a daily basis, but rather smoke intermittently or occasionally. This research has shown that intermittent/occasional smoking is a risk factor for transitioning to more regular smoking and for acute and chronic health problems (DiFranza et al., 2007; Kenford et al., 2005; McDermott et al., 2007; Bjerregaard, et al. 2006; Van der Vaart et al., 2005). Intermittent smoking among young adults is of particular interest because recent research shows that about 25% to 35% of smokers in this age group are non-daily smokers (e.g., smoked ≥ 100 cigarettes in lifetime but do not smoke every day; Lawrence et al., 2007; Minnesota Department of Health et al., 2008). Although young adults have the highest smoking rates of any age group in the U.S. (CDC, 2007; SAMHSA, 2007), little research has further described young adult smoking patterns, particularly daily versus intermittent/occasional smoking.

Most studies examining intermittent smokers in the U.S. have focused on the general adult population, showing that approximately 15–20% of adult smokers are intermittent smokers (i.e., non-daily smokers who have smoked ≥ 100 cigarettes in lifetime; Evans et al., 1992; Gilpin et al., 1997; Hassmiller et al., 2003; Hennrikus et al., 1996; Husten et al., 1998; Tong et al., 2006; Wortley et al., 2003; Zhu et al., 2003). These studies found that intermittent/occasional smokers (compared to daily smokers) tend to be younger, non-White, more highly educated, and smoke fewer cigarettes per day.

Several earlier studies have focused on intermittent smoking among college students specifically, finding that intermittent smoking is common among college students and is linked to a desire to avoid addiction and health consequences (Hines et al., 1998; Wetter et al., 1998). More recent studies describe a trend among college students termed “social smoking”—smoking that is largely limited to social situations (Moran et al., 2004; Waters et al., 2006). Social smokers tend to smoke with less frequency and intensity, have less tobacco dependence, and may have fewer intentions to quit than regular smokers (Moran et al., 2004; Waters et al., 2006).

In this study, we examine intermittent versus daily smoking among a young adult sample that includes both college students and those not attending college. Our primary aim is to determine the factors that distinguish intermittent smokers from daily smokers. Our study provides a more thorough examination than previous studies of intermittent smoking among young adults and our findings will help guide tobacco prevention, treatment, and research efforts.

Methods

Data for this study are from the Minnesota Adolescent Community Cohort (MACC) project that includes participants from Minnesota and four other upper Midwestern states (chosen as comparison states based on their demographic and cultural similarities to Minnesota). Participants were nested within 60 randomly-selected areas (i.e., geo-political units; GPUs) based on boundaries thought to reflect local tobacco control environments. A combination of probability and quota sampling methods was used to recruit participants from the 60 GPUs using modified random digit dialing. Households were called to identify those with at least one teen between 12 and 16—223,065 numbers were called to reach our sample size goals. There were 7251 known eligible households at baseline in 2000 (58.5% response rate).

In the recruitment process, standard consent procedures were followed for both parents and participants. Participants were also told the purpose of the survey (“to learn more about what kinds of things affect whether or not teenagers try or use tobacco”), that they would received $15 for each completed interview, and that they would not otherwise directly benefit from their participation. The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board approved this study.

The MACC study followed participants via telephone surveys for 15 rounds (6 month intervals) from early adolescence into young adulthood. Data for the present study were collected between April and September 2006 (round 12). Of the original 4241 participants at baseline, 3754 participated in round 12 (89% retention rate). For our analyses, we included participants who were at least 18 years old, not in high school, and who smoked at least one day in the past 30, for a final sample of 732 (47% female; 90% White). Comparisons at baseline between participants and non-respondents (who would 18–22 years old as of round 12) showed no significant differences in gender, region (urban vs. rural), or past 30-day smoking, but non-respondents were more likely to be non-White (26% vs. 10%) and slightly younger (mean = 14.6 vs. 15.0 years).

Variables

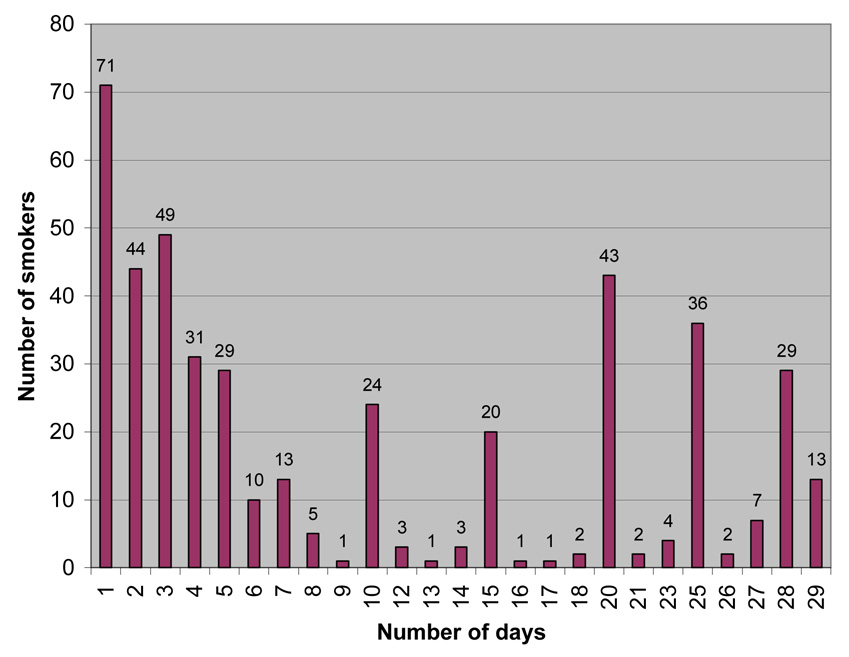

Our outcome variable was smoking status (intermittent vs. daily smoking), based on the number of days in the past 30 that the participant smoked a cigarette. We initially created a two-level variable, with those who smoked on all days in the past 30 being ‘daily smokers’ and those who smoked less than daily being ‘intermittent smokers.’ To further understand the intermittent smoking group, we examined the frequency distribution of the number of days smoked in the past 30 (Figure 1). Based on the clustering of smokers on the left end of the distribution and considering that 15 days represented a midpoint, we divided the intermittent smokers into two groups—low intermittent smokers (smoked 1–14 days in the past 30) and high intermittent smokers (smoked 15–29 days in the past 30).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Intermittent Smokers

We chose independent variables based on both theory and previous studies pertaining to factors associated with smoking behaviors. We grouped variables into six blocks: (1) Demographics. Age, gender, college (currently enrolled vs. not), region (rural vs. urban); (2) Addiction: Whether consider themselves a smoker (yes, no), how addicted to cigarettes (5-point scale), how sure they can quit (5-point scale), number of times they tried to quit (never, once, more than once), number of cigarettes per day; (3) Smoking History: Age of first cigarette, number cigarettes smoked in lifetime; (4) Alcohol Consumption: How many days in past 30 they drank at least one alcoholic beverage (1–4, 5–8, 9+); (5) Smoking in Social Situations: How often they smoke when at parties (usually, sometimes, rarely/never, don’t go), how often they smoke when at bars/clubs (usually, sometimes, rarely/never, don’t go), how often they smoke when hanging out with friends (usually, sometimes, rarely/never); (6) Smoking Exposure: Number of four closest friends that smoke, number of people in household who smoke (0 vs. ≥1).

Analyses

We conducted bivariate analyses (Chi-squares) between the three-level smoking outcome variable (low intermittent, high intermittent, and daily) and each independent variable, with all significant relationships (p < .10) included in multivariate analyses. We also conducted pair-wise tests of groups of smokers (low vs. high intermittent, and high intermittent vs. daily; p < .033 with Bonferroni correction (0.1/3)).

For multivariate analyses, we first ran models to determine which independent variables (individually and as blocks) were significantly associated with the three-level smoking variable (high intermittent as referent). Independent variables (and blocks) that were significant in these models (p < .05) were included in a second set of multivariate analyses used to determine the variance explained by adding each block of variables sequentially, starting with the demographics block and adding blocks based on theoretical proximity to our outcome variable: (1) Smoking history, (2) Addiction, (3) Smoking exposure, and (4) Smoking in social situations (Note: the alcohol consumption block was not included because it was not significant in first set of multivariate analyses). For each model, we calculated an Aldrich-Nelson pseudo-R2 and incremental F-statistic. We also calculated odds ratios for each independent variable in the final model, comparing low vs. high intermittent, and high intermittent vs. daily. To have a consistent sample size between all models, we eliminated missing values for all multivariate analyses (n = 680). We conducted all analyses in SAS 9.1 (SAS, 2004) using Proc Glimmix for generalized mixed models with GPU treated as a random effect to adjust for clustering in the sample.

Results

Among our sample of 732 young adults, 39% (n = 284) were low-intermittent smokers, 22% (n = 160) were high-intermittent smokers, and 39% (n = 288) were daily smokers. All independent variables except age were significantly associated (p < .10) with the 3-level outcome variable in bivariate analyses. Most of the pair-wise tests were also significant (Table 1; Note: To highlight differences between the groups of smokers, four variables are presented as categorical variables that were treated as continuous variables in analyses: (1) How addicted?; (2) How sure can quit?; (3) Number of cigarettes per day; and (4) Number of four closest friends who smoke).

Table 1.

Bivariate Analyses: Intermittent vs. Daily Smokers

| Type of smoker (Number days smoked in last 30) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low intermittent (1–14 days) n=284 | Hi intermittent (15–29 days) n=160 | Daily (30 days) n=288 | ||

| Independent Variables | Column Percents1 | |||

| Age | ||||

| 18 (n=69) | 10.2 | 7.5 | 9.8 | |

| 19 (n=179) | 25.7 | 29.4 | 20.5 | |

| 20 (n=211) | 29.6 | 26.9 | 29.2 | |

| 21 (n=193) | 25.0 | 26.3 | 27.8 | |

| 22 (n=80) | 9.5 | 10.0 | 12.9 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (n=388) | 57.8 | 53.8 | 47.9 | |

| Female (n=344) | 42.3 | 46.3 | 52.1 | |

| Enrolled in college a,b | ||||

| Yes (n=378) | 70.1 | 54.4 | 31.9 | |

| No (n=354) | 29.9 | 45.6 | 68.1 | |

| Region b | ||||

| Rural (n=396) | 54.9 | 45.6 | 58.0 | |

| Urban(n=336) | 45.1 | 54.4 | 42.0 | |

| Consider self a smoker? a,b | ||||

| Yes (n=426) | 6.3 | 80.0 | 98.6 | |

| No (n=301) | 93.7 | 20.0 | 1.4 | |

| How addicted? a,b | ||||

| Not at all (n=189) | 62.7 | 6.9 | 0 | |

| 2 (n=121) | 25.4 | 21.9 | 4.9 | |

| 3 (n=194) | 10.9 | 46.9 | 30.6 | |

| 4 (n=158) | 0.7 | 21.3 | 42.4 | |

| Very (n=70) | 0.4 | 3.1 | 22.2 | |

| How sure can quit? a,b | ||||

| Not at all (n=33) | 1.1 | 1.3 | 9.7 | |

| 2 (n=60) | 0.7 | 5.0 | 17.4 | |

| 3 (n=195) | 4.9 | 35.0 | 43.4 | |

| 4 (n=140) | 15.1 | 28.1 | 18.1 | |

| Very (n=304) | 78.2 | 30.6 | 11.5 | |

| Number of times tried to quit a,b | ||||

| Never (n=250) | 62.3 | 23.9 | 12.9 | |

| 1 time (n=98) | 11.7 | 16.4 | 13.5 | |

| > 1 time (n=380) | 26.0 | 59.8 | 73.6 | |

| Number of cigarettes per day a,b | ||||

| 0 (n=87) | 27.0 | 3.8 | 1.7 | |

| 1–5 (n=322) | 69.9 | 59.4 | 10.4 | |

| 6–10 (n=163) | 2.1 | 25.6 | 40.3 | |

| 11–20 (n=71) | 0.7 | 4.4 | 21.5 | |

| >20 (n=87) | 0.4 | 6.9 | 26.0 | |

| Age of first cigarette a,b | ||||

| 1–11 (n=76) | 5.7 | 7.0 | 17.0 | |

| 12–14 (n=307) | 30.4 | 44.3 | 53.7 | |

| 15–17 (n=242) | 41.1 | 34.2 | 25.8 | |

| 18+ (n=97) | 22.9 | 14.6 | 3.5 | |

| Number of cigarettes in lifetime a,b | ||||

| < 100 (n=168) | 51.4 | 11.1 | 2.9 | |

| ≧100 (n=536) | 48.6 | 88.9 | 97.1 | |

| Number of days drank in last 30 b | ||||

| None (n=104) | 12.0 | 9.4 | 19.1 | |

| 1–4 (n=224) | 27.6 | 25.6 | 36.5 | |

| 5–8 (n=161) | 26.2 | 21.9 | 18.1 | |

| 9 or more (n=242) | 34.3 | 43.1 | 26.4 | |

| Number of 4 closest friends who smoke a,b | ||||

| 0 (n=51) | 13.0 | 5.0 | 2.1 | |

| 1 (n=120) | 27.1 | 13.8 | 7.3 | |

| 2 (n=202) | 33.8 | 31.8 | 19.1 | |

| 3 (n=172) | 16.9 | 29.4 | 26.7 | |

| 4 (n=187) | 9.2 | 20.0 | 44.8 | |

| Number in household who smoke a | ||||

| 0 (n=304) | 52.8 | 39.4 | 31.9 | |

| ≧1 (n=426) | 47.2 | 60.6 | 68.1 | |

| Smoke at parties a,b | ||||

| Usually (n=370) | 10.9 | 68.8 | 79.5 | |

| Sometimes (n=171) | 39.1 | 23.1 | 8.0 | |

| Rarely/Never (n=136) | 45.1 | 3.1 | 1.0 | |

| Don’t go to parties (n=55) | 4.9 | 5.0 | 11.5 | |

| Smoke at bars a,b | ||||

| Usually (n=259) | 8.1 | 42.5 | 58.3 | |

| Sometimes (n=108) | 19.4 | 19.4 | 7.6 | |

| Rarely/Never (n=132) | 40.3 | 7.5 | 2.1 | |

| Don’t go to bars (n=232) | 32.2 | 30.6 | 32.0 | |

| Smoke with friends a,b | ||||

| Usually (n=334) | 5.0 | 48.1 | 85.6 | |

| Sometimes (n=181) | 26.0 | 44.4 | 13.0 | |

| Rarely/Never (n=210) | 69.0 | 7.5 | 1.4 | |

Values listed are percent of smoker type at each level of independent variable

Pair-wise association between low intermittent and high intermittent smokers is significant at p <.033

Pair-wise association between high intermittent and daily smokers is significant at p <.033

Pair-wise tests: Low-intermittent vs. high-intermittent smokers

Low- and high-intermittent smokers demonstrated significant differences for all independent variables except alcohol consumption and gender, with some differences markedly larger than others. A higher percentage of low-intermittent smokers were in college (70% vs. 55%), considerably fewer considered themselves smokers (6% vs. 80%) and considerably more felt they were "not at all addicted" to cigarettes (67% vs. 7%). The low intermittent group tended to start smoking at an older age, and many more of the high intermittent smokers (89% vs. 49%) smoked over 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. A higher proportion of high intermittent smokers usually smoked when at parties (69% vs. 11%), bars (43% vs. 8%), and when hanging out with friends (48% vs. 5%). More of the high intermittent smokers encountered smokers in their normative environments, with 81% (vs. 60%) reporting that at least two of their closest friends smoked and 61% (vs. 47%) having at least one smoker in their household.

Pair-wise tests: High-intermittent vs. daily smokers

High-intermittent and daily smokers demonstrated significant differences for all independent variables with two exceptions—gender and number in household who smoke—with some of the differences more striking than others. In contrast to high-intermittent smokers, most daily smokers were not college students (68% vs. 46%), more reported feeling "very addicted" (22% vs. 3%), and more tended to start smoking at an earlier age. Many more of daily smokers reported they “usually smoked” when hanging out with friends (86% vs. 48%) and said all four of their four closest friends were smokers (45% vs. 20%).

Multivariate models

In our first set of multivariate models (results not shown), the only individual independent variables that were not significant were region, "number of times tried to quit", and “number in household who smoke.” These three variables, the alcohol consumption block (which was also not significant) and age were excluded in subsequent analyses. Results of our second set of multivariate models (Table 2) show that addition of each subsequent block of independent variables explained significant additional variance, with the final model explaining 70%. Several odds ratios in the final model were also significant (Table 3). Compared to high intermittent smokers, low intermittent smokers had much higher odds of not considering themselves smokers (OR=19.57), and lower odds of being addicted (OR=0.55) and of usually (OR=0.13) or sometimes (OR=0.24) smoking with friends (vs. never). Daily smokers compared to high intermittent smokers had lower odds of being male (OR=0.55), being sure they can quit (OR=0.68) and rarely/never smoking at bars (vs. not going to bars; OR=0.16), but had higher odds of being addicted (OR=1.80) and of smoking more cigarettes per day (OR=1.14).

Table 2.

Multivariate Models: Adding Blocks of Independent Variables Sequentially

| Modela | Pseudo-R2 | Fb | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | .0580 | -- | -- |

| Demographics + Smoking history | .1560 | 15.73 | <.0001 |

| Demographics + Smoking history + Addiction | .6417 | 90.48 | <.0001 |

| Demographics + Smoking history + Addiction + Smoking exposure | .6588 | 13.33 | <.0001 |

| Final model: Demographics + Smoking history + Addiction + Smoking exposure + Smoking in social situations | .7025 | 4.73 | <.0001 |

Demographics block does not include urban/rural variable; Addiction block does not include “number times tried to quit” variable’”; Smoking exposure block does not include “number in household who smoke”

F compares model with the model one row above

Table 3.

Odds ratios of independent variables in final multivariate model

| Independent variables | Odds Ratio Low vs. High (95% CI) | Odds Ratio Daily vs. High (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender male | 0.96 (0.43, 2.14) | 0.55 (0.31, 0.95) | ||

| female | Referent | Referent | ||

| College no | 0.91 (0.40, 2.09) | 1.40 (0.80, 2.43) | ||

| yes | Referent | Referent | ||

| Age of first cig | 0.88 (0.75, 1.04) | 0.90 (0.81, 1.01) | ||

| Cigs/lifetime < 100 | 1.23 (0.44, 3.40) | 2.73 (0.83, 8.97) | ||

| ≥ 100 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Consider self a smoker? no | 19.57 (7.13, 53.75) | 0.35 (0.10, 1.32) | ||

| yes | Referent | Referent | ||

| How addicted? (1= not at all, 5=very) | 0.55 (0.33, 0.92) | 1.80 (1.27, 2.58) | ||

| How sure can quit? (1= not at all, 5=very) | 1.38 (0.87, 2.18) | 0.68 (0.52, 0.90) | ||

| Cigs/day | 1.04 (0.92, 1.18) | 1.14 (1.08, 1.21) | ||

| No. of 4 closest friends who smoke (0–4) | 1.12 (0.78, 1.62) | 0.96 (0.74, 1.25) | ||

| Smoke at parties | ||||

| 1=Usually | 0.29 (0.04, 1.91) | 0.63 (0.23, 1.75) | ||

| 2=Sometimes | 0.72 (0.11, 4.70) | 0.86(0.25, 2.99) | ||

| 3=Rarely/Never | 2.26 (0.24, 21.23) | 1.81 (0.21, 15.58) | ||

| 4=Don’t go | Referent | Referent | ||

| Smoke at bars | ||||

| 1=Usually | 0.51 (0.17, 1.51) | 1.13 (0.61, 2.10) | ||

| 2=Sometimes | 0.62 (0.22, 1.75) | 0.61 (0.25, 1.50) | ||

| 3=Rarely/Never | 2.83 (0.75, 10.63) | 0.16 (0.03, 0.78) | ||

| 4=Don’t go | Referent | Referent | ||

| Smoke with friends | ||||

| 1=Usually | 0.13 (0.33, 0.50) | 3.87 (0.59, 25.42) | ||

| 2=Sometimes | 0.24 (0.09, 0.68) | 1.47 (0.23, 9.43) | ||

| 3=Rarely/Never | Referent | Referent | ||

Note: values in bold are significant at p < .05

Discussion

Among our many findings perhaps the most important is that, unlike previous studies, we identified two distinct groups of intermittent smokers, with low intermittent smokers differing sharply from high intermittent smokers and high intermittent smokers being distinctly different from daily smokers on most characteristics. However, for some characteristics high intermittent smokers aligned more closely with daily smokers and on others they represent a clear midpoint between daily smokers and low intermittent smokers. Interestingly, contrary to studies among the general adult population, intermittent smokers did not differ from daily smokers on age. This may be in part due to our sample being limited to young adults (a somewhat narrow age range).

In our final multivariate model, a high proportion of variance (70%) between levels of smoking is explained by our independent variables, with the addiction block explaining most of this variability. We also found that the addition of each block of independent variables explained additional variance, indicating that all the factors were important in distinguishing the three groups. Odds ratios further confirm the distinctions between groups. Clearly, tobacco prevention and treatment programs must not consider intermittent young adult smokers as one homogeneous group with the same characteristics and behaviors.

Furthermore, unlike previous studies that suggest many young adult intermittent smokers are social smokers, we found that nearly all of the low-intermittent smokers do not usually smoke when they are with friends, at bars, or at parties, and nearly one-third of the low and high intermittent smokers don’t even go to bars. Although our survey did not specifically ask if smoking is largely limited to social situations, high intermittent smokers may more closely resemble social smokers, as most usually smoke when they go to parties and about half usually smoke when they are at bars or with friends.

The tobacco industry has long known that the young adult period is the time when daily consumption of cigarettes increases until solidifying into heavy smoking as older adults (Ling & Glantz, 2002). Our sample of 18–22 year-old adults exemplifies these unsettled smoking patterns, with roughly equal numbers in each group of low intermittent, high intermittent and daily smokers. Our data emphasize that it is important for researchers and intervention professionals to recognize the varied smoking patterns among this age group and how they differ from the more stable patterns of adult smokers and the experimental patterns of adolescents (Adelman, 2006).

Several limitations should be noted. First, our sample is from the Midwestern U.S. which limits the generalizability to the U.S. as a whole and other countries. However, our sample, unlike others examining non-daily smoking among young adults, does include both college students and those not attending college, and includes participants from rural and urban regions. Secondly, we were not able to analyze how race/ethnicity differed among smoking groups of young adults because our sample was largely White. Finally, our study is cross-sectional which prevents us from determining how intermittent smoking patterns change over time.

Future studies are underway using MACC data to determine intermittent smoking patterns from adolescence through young adulthood. Our study provides valuable information to guide future studies on intermittent smoking, as well as to guide tobacco prevention and treatment professionals in addressing intermittent smoking patterns and behaviors among the young adult population, particularly given that intermittent smokers are at risk for escalation to more frequent and heavier smoking.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institute of Health R01-CA086191, Jean Forster, Principal Investigator. We thank Rose Hilk for her assistance with data management, and Clearwater Research Inc. for conducting the telephone surveys.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adelman WP. Tobacco use cessation for adolescents. Adolescent Medicine Clinics. 2006;17(3):697–717. doi: 10.1016/j.admecli.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerregaard BK, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Sorensen M, Frederiksen K, Tjonneland A, Rohrmann S, Linseisen J, Bergman MM, Boeing H, Sieri S, Palli D, Tumino R, Sacerdote C, Bueno-De-Mesquita HB, Buchner FL, Gram IT, Braaten T, Lund E, Hallmans G, Agren A, Riboli E. The effect of occasional smoking on smoking-related cancers - in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Cancer Causes & Control. 2006;17(10):1305–1309. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vol. 56. 2007. Nov 9, Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2006; p. 44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, O'Loughlin J, Pbert L, Ockene JK, McNeill AD, Hazelton J, Friedman K, Dussault G, Wood C, Wellman RJ. Symptoms of tobacco dependence after brief intermittent use: the development and assessment of nicotine dependence in Youth-2 study. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(7):704–710. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans NJ, Gilpin E, Pierce JP, Burns DM, Borland R, Johnson M, Bal D. Occasional smoking among adults: Evidence from the California Tobacco Survey. Tobacco Control. 1992;1(3):169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin E, Cavin SW, Pierce JP. Adult smokers who do not smoke daily. Addiction. 1997;92(4):473–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassmiller KM, Warner KE, Mendez D, Levy DT, Romano E. Nondaily smokers: Who are they? American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(8):1321–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennrikus DJ, Jeffery RW, Lando HA. Occasional smoking in a Minnesota working population. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(9):1260–1266. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.9.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines D, Fretz AC, Nollen NL. Regular and occasional smoking by college students: Personality attributions of smokers and nonsmokers. Psychological Reports. 1998;83(3):1299–1306. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.83.3f.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husten CG, Mccarty MC, Giovino GA, Chrismon JH, Zhu BP. Intermittent smokers: A descriptive analysis of persons who have never smoked daily. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(1):86–89. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenford SL, Wetter DW, Welsch SK, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Progression of college-age cigarette samplers: What influences outcome. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(2):285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence D, Fagan P, Backinger CL, Gibson JT, Hartman A. Cigarette smoking patterns among young adults aged 18–24 years in the United States. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(6):687–697. doi: 10.1080/14622200701365319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: Evidence from industry documents. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(6):908–916. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdermott L, Dobson A, Owen N. Occasional tobacco use among young adult women: A longitudinal analysis of smoking transitions. Tobacco Control. 2007;16(4):248–254. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.018416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clearway Minnesota, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota, and Minnesota Department of Health. Creating a healthier Minnesota: Progress in reducing tobacco use. Minneapolis, Minnesota: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moran S, Wechsler H, Rigotti NA. Social smoking among U.S. college students. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):1028–1034. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0558-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. SAS/STAT 9.1 User's guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville MD: Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. 2008 (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-34, DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4343)

- Tong EK, Ong MK, Vittinghoff E, Perez-Stable EJ. Nondaily smokers should be asked and advised to quit. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Vaart H, Postma DS, Timens W, Hylkema MN, Willemse BWM, Boezen HM, Vonk JM, De Reus DM, Kauffman HF, Ten Hacken NHT. Acute effects of cigarette smoking on inflammation in healthy intermittent smokers. Respiratory Research. 2005;6(22) doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters K, Harris K, Hall S, Nazir N, Waigandt A. Characteristics of social smoking among college students. Journal of American College Health. 2006;55(3):133–139. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.3.133-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter DW, Kenford SL, Welsch SK, Smith SS, Fouladi RT, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Prevalence and predictors of transitions in smoking behavior among college students. Health Psychology. 2004;23(2):168–177. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortley PM, Husten CG, Trosclair A, Chrismon J, Pederson LL. Nondaily smokers: A descriptive analysis. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5(5):755–759. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000158753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SH, Sun JC, Hawkins S, Pierce J, Cummins S. A population study of low-rate smokers: quitting history and instability over time. Health Psychology. 2003;22(3):245–252. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]