Abstract

Social theorists have long recognized that changes in social order have cultural consequences but have not been able to provide an individual-level mechanism of such effects. Explanations of human behavior have only just begun to explore the different evolutionary dynamics of social and cultural inheritance. Here we provide ethnographic evidence of how cultural evolution, at the level of individuals, can be influenced by social evolution. Sociocultural epistasis—association of cultural ideas with the hierarchical structure of social roles—influences cultural change in unexpected ways. We document the existence of cultural exaptation, where a custom's origin was not due to acceptance of the later associated ideas. A cultural exaptation can develop in the absence of a cultural idea favoring it, or even in the presence of a cultural idea against it. Such associations indicate a potentially larger role for social evolutionary dynamics in explaining individual human behavior than previously anticipated.

Keywords: Taiwan Aborigines, cultural evolution, demographic change, marriage customs

One of the greatest challenges of social science is to account for the unintended consequences of human actions (1). Social theorists (2–6) have long recognized that changes in social order—for example, from feudalism to capitalism—have consequences for cultural content. However, they have not been able to provide a mechanism at the level of individual behavior which can explain how it has such effects. Recently, evolutionary perspectives have converged on a possible solution: society as an evolutionary inheritance track distinct from genes, culture, and the ecological environment (7–10).

Human social order is a series of overlapping, hierarchical structures of roles (11–13), sometimes referred to broadly as stratification or power. Such structures are defined by expectations of behavior for role holders. Epistemologically, a role is the set of shared expectations of behavior of individuals grouped under that role's label. People ordinarily refer to specific role structures in terms of the character of the ties that connect the role holders, for example, political ties (such as police–community relations). Being a competent member of any society requires understanding the specific expectations associated with the roles one holds and with the roles one regularly encounters.

Culture is a series of overlapping, nested sets of meaningful ideas (14), often referred to as symbolic or meaning systems. Such ideas are expressed and learned behaviorally, yet internalized in individual minds (15–16). Every part of these meaning systems is in constant flux, and meaning systems do not lead unambiguously to human behavior. Epistemologically, a cultural idea is a shared abstraction, represented by a symbol, which derives from ideas that are similar enough to be considered versions of one another and that are held by individuals in a population (17). A specific culture may be referenced in terms of an idea set shared by its individual members; e.g., American culture by “rugged” individuals. Being a competent member of any culture requires understanding the specific cultural ideas associated with the symbols one regularly uses and encounters.

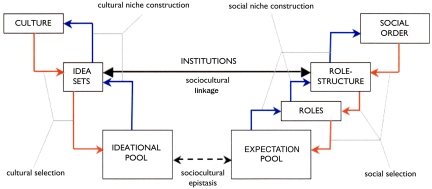

Culture and social order are group-level properties. Cultural ideas aggregate to idea sets, and to “the culture” of a population (Fig. 1), but the important group-level property of culture is the way that cultural ideas depend on belief and perception of others' belief. Cultural ideas are (i) shared by some percentage of a population and (ii) meaningful because they are either believed (i.e., considered truth) by some percentage of that population or else associated with one or more other ideas believed by some percentage of that population. For example, spirits of the dead need offerings. Many—but nowhere near all—people in Taiwan and China believe this cultural idea. Meaningful ideas have the potential to motivate individuals' behavior—for example, in ancestor worship—due to an individual's belief or perception that a significant number of other people in the population believe.

Fig. 1.

Cultural inheritance track and social inheritance track with cross-track associations. Cultural epistasis and social epistasis are not shown here but occur within the ideational pool and the expectation pool, respectively.

By contrast, although role expectations must be shared by some percentage of a population, their most important group-level property occurs through aggregation—to roles, role structures, and “the social order” of a population, sometimes called “political economy” or “mode of production” (Fig. 1) (cf. ref. 18). Role expectations must accurately indicate how an individual can achieve a specific role or how, as a holder of a specific role, an individual can maintain that role through appropriate interactions with others (cf. ref. 19).

Social and cultural units relate to different informational categories (roles versus beliefs); they are learned in different ways (experience versus interpretation), and have different accuracy and consistency requirements (necessary versus unnecessary). Cultural units may also masquerade as social units. For example, the cultural idea of supernatural forces is distinct from role expectations of a religious specialist and a believer's expectations of a deity. Christians and non-Christians alike can comprehend the idea of Jesus as God and expect that a priest will know how to serve communion. However, believers' expectations of a deity are cultural, even though they mimic the form of social units. Non-Christians do not share believers' expectations about Jesus' involvement in people's lives. Such distinctions can also be made outside the realm of religion. Elderly Han women who once had their feet bound, their unbound descendants, and outside observers can all comprehend the cultural idea that girls ought to have bound feet and expect that Han mothers knew how to bind feet. However, whether the expectation that footbinding would improve a girl's marital opportunities was a true role expectation or a cultural idea masquerading as a role expectation requires empirical evidence that most footbound girls did marry “better” than girls who never bound feet.

Social order and culture are intertwined in daily life, but they have different dynamics of transmission and influence on human behavior. Cultural transmission occurs not merely when individuals learn of a cultural idea from another person but when they internalize the idea as meaningful (they believe it or think others generally believe it). Cultural transmission thus has three aspects: broadcasting, reception, and internalization (7, 9; cf. refs. 15, 20–21). Any of these transmission aspects can be affected by natural selection (of the individuals who carry cultural ideas) or cultural selection, where the ideas that an individual already has internalized influence his/her broadcasting, reception, or internalization of subsequent ideas to which she/he is exposed (Fig. 1) (7, 21–24; cf. refs. 4–6). There is a feedback from individuals to the larger culture—cultural niche construction—via the back-influence of belief (or disbelief) on whether particular ideas are accepted as meaningful in a population (8, 24; cf. ref. 25). It benefits individuals to pass on cultural ideas that they hold because it maintains their cultural competence and ensures that their behavior remains culturally approved.

Social transmission occurs when individuals internalize expectations that they abstracted from observation (or reports) of the negotiated outcomes of social interactions. Individuals bring to each specific interaction expectations about the behavior of others, and the expectations people already have will influence the behavior(s) that they accept from others. What behavior actually ensues depends on a negotiation process via speech and actions (26); this process constitutes social selection. Individuals benefit by perpetuating existing expectations because it maintains their social competence and may improve or defend their social rank. Thus, people resist unexpected behavior. Ease, cost, and degree of resistance are based on the relative rank of the interacting individuals. Nevertheless, individuals can successfully negotiate an unexpected ability to achieve a role or unexpected behavior for a role holder. For example, some Han Chinese virilocal brides successfully negotiated having fewer children and getting more help with child care than their mothers-in-law initially wanted (27). Social precedents constitute social niche construction because they feedback to change shared expectations of roles (Fig. 1). They can potentially influence the entire social order via the behavior of a few individuals positioned at pivotal points in the hierarchy or via the aggregated behavior of many individuals.

Social dynamics and cultural dynamics refer to processes—e.g., transmission and selection—that result in persistence or change in the role-related expectations held by a population over time (an expectation pool) and the content or frequency of cultural ideas held by a population over time (an ideational pool), respectively (Fig. 1). However, such changes can also result from association, which occurs within each track and also across tracks. Associations can be seen quantitatively. For example, as discussed in Results, the shift in marriage form for plains Aborigines in early 20th-century Taiwan was strongly associated with enforcement of a ban on footbinding among the Han, which the Japanese colonial government began in 1915. Between 1906 and 1915, 33 of the 95 marriages recorded by the Japanese police for all plains Aborigines in Danei Township were uxorilocal (where a man married to his wife's natal home). (See refs. 28 and 29 for a description of these records.) However, after footbinding was banned, only 37 of 269 plains Aborigine marriages during the remainder of the colonial period, 1916–1945, were uxorilocal. In other words, there is a statistically very significant association (P < 0.001 using χ12) between the frequency of uxorilocal marriages among Aborigines and the presence or absence of footbinding among the Han.

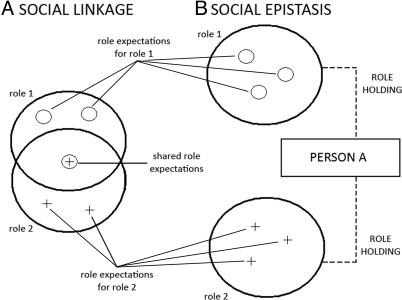

However, because most available quantitative data are about practices and because the frequency of practices do not reliably predict the frequency of related ideas (28), understanding the association of the underlying cultural or social units requires further qualitative interpretation. Within the cultural track, cultural linkage occurs when two ideas transmit together (Fig. S1). For example, the idea of Jesus as God and the idea that humans are sinners generally transmit together, as do the ideas of counting and whole numbers. In cultural epistasis, the content of one idea is a logical consequence of the content of the associated idea(s) (Fig. S1). For example, the idea of presenting offerings to the dead logically requires the idea that people have spirits which continue to exist after death. Just as physical proximity on a chromosome can lead to genetic association during the transmission process (which can affect evolution), the semiotic overlap of one idea necessarily implying subsequent ideas leads to cultural epistasis. Within the social track, role expectations related to a single role are associated by definition, but the association of two roles can lead to unexpected associations between specific role expectations. Social linkage occurs when expectations for two (or more) roles are “transmitted” together—because they share at least one role expectation explicitly linking them (Fig 2). For example, the roles can be simultaneously recruited and filled, as in the roles of bride and groom. In social epistasis, expectations for two or more roles overlap for the structural reason that one individual holds multiple roles (Fig. 2). For example, a young woman who is both a bride and a spirit medium is subject to expectations for both roles.

Fig. 2.

Social linkage and social epistasis. (Left) Linkage occurs because Role 1 and Role 2 may be held by the same person or different people. They are linked by a shared role expectation that explicitly associates them. (Right) Epistasis entails that Role 1 and Role 2 are structurally associated because they are both held by Person A.

Two important associations occur across the social and cultural inheritance tracks. An institution is the integration of an idea set into a social role structure, such that the cultural ideas and role expectations reinforce each other (cf. refs. 11, 16). Institutional associations exemplify sociocultural linkage (Fig. 1), because ideas and role expectations are transmitted together. This linkage confers moral weight on role expectations—the movement from “is” to “ought” against which Hume warned. Sociocultural epistasis is an association between cultural ideas and role expectations due to structural overlap, as when one individual is associated with multiple sets of role expectations (by holding multiple roles or the same role in multiple role structures) or the same individual holds multiple cultural ideas (Fig. 1). Strings of epistatic association are possible, as in the example of marriage and footbinding (discussed in Analysis).

One consequence of cross-track associations is cultural exaptation, a practice that is currently cultural (in other words, currently associated with a cultural idea assumed to be motivational) but was not associated with that cultural idea when the practice was adopted (Fig. S2).* Each practice has a specific history: If, after its origin, a practice becomes associated with a cultural idea, then the idea is historically extrinsic to that practice's origin and the practice is a cultural exaptation. The practice may have been social upon adoption or it may have been associated with a different cultural idea than the one currently associated with it. Another way to conceptualize it is that a cultural exaptation is a practice in a population in the absence of a cultural idea directly motivating the practice or even in the presence of a cultural idea against such a practice; the practice later comes to have an association with a cultural idea, which may post hoc be assumed to motivate it (31; cf. ref. 32). The later association with the cultural idea can occur through a string of associations between ideas and role expectations. For example, a Taiwanese spirit medium is connected both to the religious practices she/he conducts but can also be connected to marriage practices as a bride or groom.

The cultural adaptiveness of particular ideas is the degree to which those ideas motivate practices by individuals holding them (i.e., they are “functional” strictly within the cultural environment of ideas). In other words, cultural adaptiveness requires both a regularly practiced behavior (which occurs with a reasonable frequency across the population) and an association of that behavior with a “motivationally charged idea” (16) resulting in that practice. Cultural exaptation, then, is a cultural practice whose origin does not derive from the success of the associated idea via cultural transmission and cultural selection.†

It is much easier to identify and model the frequency of behaviors than to identify or model the association of behaviors with specific ideas (but see refs. 16, 28, 31, and 33–35). Indeed, although it is commonly known, and occasionally documented, that what people say is often different from what they do (36–37), there are very few empirical data across individuals in any population about the association of presumptive motivational ideas with cultural practices. It is a question for further investigation how empirically common cultural exaptations are, but their presence suggests that some aspects of culture will have a different evolutionary dynamic from any previously explored.

Results

Footbinding and Religious Practices.

Here we present an ethnographic case study showing sociocultural epistasis and cultural exaptation via the unexpected association of footbinding with two kinds of religious practices—Thai Tsoo worship and grave-site rituals—in early 20th-century Taiwan (7, 9, 38–39). These associations occur via the connection of each practice to marriage, an institution that structures recruitment for kinship roles, which are among the most fundamental roles in any society (40).

Footbinding was associated with marriage because footbinding identified the ethnic border between Han and plains Aborigines, an endogamous boundary.‡ By 1900, three Aborigine communities in southwestern Taiwan had already adopted Han Chinese language and many Han social and cultural practices, but they had not adopted the locally common practice of binding their daughters' feet. This absence marked them as Aborigine. Neighboring Han would not marry their daughters into these communities (as first-time brides), nor would they accept Aborigine brides for their sons in the preferred virilocal form of marriage (where women marry to their husband's household). Some poor Han men, who could not get a bride any other way, did marry into the Aborigine villages uxorilocally (to their wife's home), a form of marriage Han generally consider shameful (29, 41, cf. ref. 18).

Footbinding's structural connections are most readily seen by its removal. After the 1915 ban on footbinding, the ethnic identity and marriage patterns of these (formerly) Aborigine communities changed. Nearby Han communities began to exchange brides in virilocal marriages with them. It took three years to negotiate one prominent virilocal marriage of a first-time Han bride into one of these plains Aborigine communities. The groom's father—a Han man who had himself married uxorilocally into the plains Aborigine community—wanted a Han daughter-in-law. Bride exchange became frequent, as more parents in the (formerly) Aborigine villages arranged virilocal marriages for their children. (Some plains Aborigine parents wanted to keep daughters nearby by having them marry local Han, a very different motivational idea for virilocal marriages than those expressed by Han.) Whereas both virilocal and uxorilocal marriage forms had once been common (and neither had been stigmatized) in these villages, after 1930 or so, virilocal marriage became close to universal. Between 1936 and 1945, 81 of 85 marriages recorded for (former) Aborigines in Danei Township were virilocal.

These structural changes in marriage yielded immediate consequences for women and subsequent consequences in one village for the religious practices dedicated to the Aborigine deity Thai Tsoo (Fig. S3). Because of competition between the traditionally female religious specialist role of Thai Tsoo spirit medium and the new recruitment of most women as virilocal brides, this spirit-medium role passed from women to men. Changing bridal recruitment, which can also be thought of as changing frequencies of marriage form, overcame widespread agreement among villagers that the role ought to be held by a woman.

In the 1930s, “Tan A-lien” (the last female spirit medium) sought to train as her successor “Lim Mui-moe” (a younger village woman). Lim reported that she had refused Tan because she was unmarried at the time and expected to marry virilocally out of her natal village. This refusal was based on a structural consideration: Lim expected the new virilocal recruitment process for becoming a bride to preclude her from being able to fulfill the role expectations of spirit medium. Lim did marry virilocally but within the village (to the son of the woman who assisted Tan in rituals). Nevertheless, Lim still refused to train as a spirit medium because she would have small children that would prevent her from traveling to perform the healing rites expected of the Thai Tsoo spirit medium. This second refusal reflects Lim's expectations regarding childcare in an extended household. Women in a virilocal household included not only the bride herself and her mother-in-law but potentially also sisters-in-law—women who had also married virilocally into the household. Lim's refusal reflected her assessment—which ethnographic data on virilocal Han brides in Taiwan (42) supports as accurate—of the low probability that her sisters-in-law would care for her young children while she traveled to perform rituals. (Lim's mother-in-law was not available to provide childcare because, as Tan's assistant, she too would be leaving the house to attend rituals.) Had Lim married uxorilocally, within her natal household, the outcome might have been different because she could have asked her own mother or sisters to care for her children. Expectations were different for an uxorilocal bride and a virilocal bride.

The change in marriage recruitment, to nearly universal virilocal bride exchanges, necessitated a shift in recruitment for the role of Thai Tsoo spirit medium. Tan could not find a woman to train, even though many villagers reported community agreement that the role should have passed to a woman (born in the village). Finally, she trained her son. Passing this influential community role to men (no woman has held it since) had consequences. Male spirit mediums appointed male ritual assistants (changing recruitment for yet another role) and made changes in the practices of Thai Tsoo worship. They added incense in the temples, raised altars from floor to chest level, increased the number of vases representing the deity, introduced a written banner, and modified temple architecture (Fig. S3). Many of the new practices were drawn from Han folk religion. By the 1990s, most villagers spoke of these Han-derived practices as neighboring Han did. Adoption of Han practices strengthened the association of males with the Thai Tsoo spirit-medium role because Han spirit mediums are usually men.

Increasing virilocal bridal recruitment also affected grave-site rituals (Fig. S4). Before these marital exchanges, the plains Aborigine communities had not practiced Han tombsweeping rituals common among Han in Taiwan. Some plains Aborigines did not even mark burial sites, thereby precluding later grave-site rituals. After virilocal bridal recruitment became common, grave-site rituals jumped from rare to annual for the three years after the kinds of events that brought households into increased contact with their Han in-laws: funerals, marriages, and the birth of a son. The ability to perform such annual rites required the foresight of marking graves sufficiently to locate the grave site after a year's plant growth (Fig. S4 and Fig. S5). By the 1990s, the cultural idea that families ought to provide annual grave-site rituals had become widespread.

Analysis: Institutional Association and Sociocultural Epistasis.

A string of associations connects the practice of footbinding to bridal role to spirit-medium role to religious practices. Whether the association between footbinding and marriage for the Han population is seen as institutional or epistatic divides the current debate in China studies over footbinding. Analysis of elite views of footbinding suggests that it was related to cultural ideas about beauty, sexuality, and gender construction (43) and necessary for a woman to marry. Thus, this set of cultural ideas was integrated into the kinship role structure—an institutional association which conferred moral weight on bridal role expectations of footbinding. Although this conclusion may hold for the top 5% or 10% of China's late-imperial-period Han population (but see ref. 44), analysis suggests that, for Han commoners, footbinding was institutionally associated not with marriage but with handcraft production (45). Thus, for commoners, footbinding's association with marriage was epistatic because footbound, unmarried girls who constituted the handcraft labor force were also recruited for the role of (virilocal) bride. The overlap created by the same category of person—footbound, unmarried girls—holding crucial roles in both role structures allowed social epistasis (Table S1).

For plains Aborigines and Han, footbinding was institutionally associated with the social role of bride because it defined an ethnic endogamous boundary. Han cultural ideas regarding what constituted civilization were integrated with the kinship role structure in a way that restricted the category of woman who could be recruited as a virilocal (first-time) bride for a Han groom: The woman had to be Han, as indicated by having bound feet. Interestingly, footbinding may have remained the final ethnic marker for epistatic reasons because who held parental roles influenced whether binding occurred. Han mothers bound their daughters' feet, and as a consequence, it was Han women who held the knowledge of how to enact the practice, but most intermarriage was between Han men and Aborigine women, neither of whom knew how to bind feet (7, 39).

The association between the bridal role and Thai Tsoo spirit-medium role was also social epistasis: Both roles recruited holders from the same category of person (young women). This association was influenced by tensions among sisters-in-law, which were not institutionalized. In fact, they went against cultural ideas about how sisters-in-law ought to treat each other, but such tensions were common enough that there must have been an observationally based role expectation about them shared by many people. Marriage—which occurred for almost all rural women (29)—placed young women into a specific, hierarchically networked social role (virilocal bride). That placement affected which other roles young women could hold due to direct competition between the expectations of different roles. Bridal role expectations may have won because of either social or cultural dynamics, but it was a change in the social niche (due to precedents) that created the competition, because two roles could not be held at the same time.

The association of the Thai Tsoo spirit-medium role with Han religious practices is sociocultural epistasis because once men held the Thai Tsoo spirit-medium role they claimed a spirit-medium role in the Han folk religious structure. As a first consequence, these men became subject to role expectations for Han spirit mediums. For example, they could join pilgrimages to Han temples but would be expected to behave like Han spirit mediums, using incense offerings (Fig. S3) and self-flagellaton. As a second consequence, they brought these Han religious practices into Thai Tsoo worship.

A second string of associations occurs in this ethnographic case: The practice of footbinding to bridal role to grave-site rituals to grave markers. The first association, between footbinding and brides, has been discussed. The second association, between brides and grave-site rituals, was sociocultural epistasis because the spread of grave-site rituals in the Aborigine villages came as a consequence of changes in bridal recruitment. Bringing Han women into the villages as virilocal brides brought women with different cultural ideas and different role-expectations from their Aborigine in-laws on many topics, including grave-site rituals. Han brides—and their natal families—would have expected momentous events, such as a son's birth, to be presented to the ancestors during annual grave-site rituals, and noted the absence of such rituals. These role expectations held by affines apparently led plains Aborigine families to adopt grave-site rituals (in which they did not necessarily believe). The third association is cultural epistasis because grave-site rituals necessitated grave markers. Rituals could only be performed a year or more after a burial if grave sites could be found (Fig. S4 and Fig. S5).

In both of these strings, structurally induced changes occurred because there was a newly recruited category of person in crucial roles: Han as affinal kin and men as Thai Tsoo spirit medium. Evolution of specific practices, and (as we discuss in Analysis: Cultural Exaptation) of cultural ideas, occurred because their association with role expectations changed due to a renegotiation of role-holder recruitment.

Analysis: Cultural Exaptation.

This ethnographic case provides three examples of two different kinds of cultural exaptation. First, practices spread in the absence of a supporting idea. The adoption of grave markers and the performance of grave-site annual rituals spread based on the expectations of a newly recruited category of person—Han—in the role of affinal kin. Han cultural ideas about ancestor worship may have motivated Han in-laws' own practice of grave-site rituals and their expectations of its practice by their new kin. However, the former plains Aborigines appear to have adopted the practice without themselves believing. It could be that they were motivated by structural concerns—maintaining the good opinion of their Han affines—or it could be the former plains Aborigines' referent population shifted to include their Han affines, who did believe. In the latter case, the ideas would have become meaningful and so cultural, even without the former plains Aborigines themselves believing in them.

In the second kind of cultural exaptation, a practice appeared in the presence of an antithetical cultural idea. The fact that elderly villagers decades later clearly and uniformly remembered the belief that a woman ought to be Thai Tsoo spirit medium suggests that cultural selection pressure against a man taking over the role must have been strong. Thus, a male as spirit medium did not merely have no cultural adaptiveness in the 1930s; it was culturally maladaptive (likely to be eliminated because of competing cultural ideas). However, men took over the role of Thai Tsoo spirit medium. The change in social recruitment is a cultural exaptation because it was driven not by the idea that men ought to hold the role but by changes in marriage.

The third example, which shows both types of cultural exaptation, occurred once men held the role of Thai Tsoo spirit medium. In the first type, men instituted changes in daily religious practices, which spread without being driven—or even accompanied—by the later associated idea. In the second type, some practices may have even spread in the presence of a cultural idea opposing the practice. A few elderly residents in 1991 criticized the introduction of incense and the multiplication of vases as an inappropriate borrowing of Han practices, even though most of the community had long since accepted these practices (Fig. S3). Most villagers regularly provided incense offerings and viewed these offerings as meaningful and appropriate (7, 9, 38–39).

These practices all represent cultural exaptations because their origins were not due to acceptance of the later associated ideas. Rather, they owe their origins to sociocultural or social epistasis: The practices were linked to specific social roles embedded in one of the hierarchical yet dynamic role structures that constitutes society. When forces shifted the categories of individuals regularly recruited to those roles, it had unintended consequences for at least some of the practices associated with those roles. With time, the associated ideas spread in the population. However, these ideas followed—rather than preceded—the practices, because in 1991 and 1992 the frequency of the ideas was still unexpectedly lower than the frequency of the practice (31). Such ideational variation in relation to an accepted cultural practice may be a general indicator of cultural exaptation.

Discussion: Evolutionary Cultural and Social Dynamics.

No one would have predicted that changes in footbinding in southwestern Taiwan would lead to changes in religious and grave-site rituals. One reason these unintended consequences seem unintuitive is that people are unaware of how associations across distinct social and cultural inheritance tracks—which have different evolutionary dynamics—affect behavior.

Here, we have focused on human practices—actions by individuals that are similar enough to be considered versions of one another and that are regularly repeated. Practices can be motivated by beliefs or role expectations, and they have the potential to feedback on and influence the informational units from which they come (Fig. S1). Observers may assume that practitioners believe the associated ideas, thus perceiving these ideas as meaningful; this is an example of cultural niche construction (24). Such an effect on perception is implied by neo-Confucian promotion of orthopraxy (31). Practices can also influence role expectations—via social niche construction when a social precedent becomes a practice, and via social epistasis when a structural overlap leads to the association of practices from one role with another role.

Cross-track associations add complexity. Institutions integrate an idea set and a role tructure via the linkage (cotransmission) of cultural ideas and social role expectations (Fig. 1). This linkage contributes to persistence because practices that are simultaneously motivated by both beliefs and role expectations are more resistant to change. By contrast, sociocultural epistasis facilitates change by associating practices motivated by one cultural idea (or idea set) with a new role or with an institution to which it had not been previously connected (Fig. 1). Such associations may lead to new logical implications (e.g., 9, 31) and thus variation in cultural epistasis. Cultural exaptations indicate that such associated changes have occurred.

We suggest the most important dynamic of social evolution (evolution in the social inheritance track) may be the recruitment process (40). In other words, changes in expectations about how to recruit individuals to fill roles (including which category of individuals may fill a particular role) may be the selection process that contributes most to the descent with modification of the social order. Such social selection is often driven by individuals pursuing their social self-interest—negotiating to improve or maintain their position in the hierarchical networked structure of roles. Specific successful negotiations introduce microlevel variation in expectations. For example, the uxorilocally married Han father-in-law took three years to negotiate a virilocal bride for his son, a marriage that would have improved his position with Han and that other villagers would recognize once enacted. At the community level, the apparent transformation in marriage form required a change in the recruitment of many individuals to the same bridal role in different households; this transformation is an aggregation of negotiations across individuals. How many individual events of the new recruitment process were needed to reach a tipping point that sparked a rapid increase in such negotiations remains an interesting question (31). We speculate that such tipping points depend on the relative position and connections of the individual broadcasters (innovators) and acceptors in the role structure (20).

Social structure is crucial to cultural evolution (evolution in the cultural inheritance track) (see Table S1). To be transmitted, ideas must be enacted—put into behavioral form—by individuals who are necessarily embedded in a social role structure. Role holders simultaneously have multiple connections across the structure, hierarchical positions relative to other roles, associated cultural ideas, and practices. Thus, practices are both associated with—and potentially constrained by—social roles. Marriage—a recruitment process for certain kin roles—affected the cultural ideas that could be enacted, both by individuals in specific roles and, sometimes, by an entire category of people regularly recruited to a role. Being a daughter-in-law or a married daughter—basic household-level structure—“changed everything” (as one elderly woman remarked) with respect to carrying out daily obligations, such as child care, and led to appointing a male Thai Tsoo spirit medium against the belief of villagers. Maintenance of men as role holders has threatened the perpetuation of the belief in the Thai Tsoo spirit medium as a female role. Change in marriage drove the role takeover, and our analysis offers an explanation of how and why the takeover occurred as well as why marriage changed. We consider individuals' motivations to analyze the origins of behavioral practices. Associations among roles, practices, and ideas can create unexpected consequences due to a change at any of the connection points. These associations deserve further consideration in the evolutionary assessment of human behavior.

Materials and Methods

M.J.B. collected the ethnographic data presented here (in human-subjects-approved research) during semistructured interviews in four communities in southwestern Taiwan from August 1991 to July 1992. These abbreviated life histories focused on personal and observed practice of marriages, funerals, burials, worship, and other customs (7, 38). A few interviews focused exclusively on religious traditions and community oral history. Most people interviewed had themselves been considered plains Aborigine (the rest Han).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank William H. Durham, Joseph Felsenstein, Hill Gates, K. Ann Horsburgh, David Laitin, Kylea Liese, Mikhail Lipatov, John Odling-Smee, Allison Rhines, Deborah Rogers, Damian Satterthwaite-Phillips, James Truncer, and students in ANTHRO 302 for useful discussion and comments. We thank Yang Wen-shan, current director of the Program for Historical Demography at the Academia Sincia in Taiwan, as well as Arthur Wolf and Chuang Ying-chang, for permission to use the Danei demographic database. The ethnographic research was funded by the American Council of Learned Societies, the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation for Scholarly Exchange, the Pacific Cultural Foundation, and the Institute of Ethnology at the Academia Sinica. Research was also supported in part by Stanford University's Institute for Research in the Social Sciences and the Morrison Institute for Population and Resource Studies. M.W.F. is supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant GM28016

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0907520106/DCSupplemental.

Gould and Vrba (30) originally defined exaptation broadly as a morphological trait whose (genetic) evolutionary origin is distinct from its current, adaptive function. Currently in population genetics, exaptation has a more focused definition: when a change in fitness of one trait in one set of environments (caused externally to the organism) leads to the sudden importance to fitness of another (possibly genetic) trait previously present in the organism but not relevant or functional. In defining cultural exaptation, we follow Gould and Vrba's broader approach.

There may also be social exaptations: practices that are currently social—i.e., currently associated with a role expectation assumed to be motivational— that were not associated with that social role expectation when the practice was adopted. We do not address them here.

Han is the Chinese term for those most Westerners think of as ethnic Chinese. Aborigines are the indigenous Austronesian peoples of Taiwan.

References

- 1.Popper K. The Myth of the Framework. London: Routledge; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marx K. Karl Marx: Selected Writings. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber M. Weber: Selections in Translation. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge Univ Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durkheim E. Emile Durkheim: Selected Writings. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge Univ Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourdieu P. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge Univ Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foucault M. Power/Knowledge. New York: Pantheon; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown MJ. Seattle: Univ Washington; 1995. “We Savages Didn't Bind Feet”—The Implications of Cultural Contact and Change in Southwestern Taiwan for an Evolutionary Anthropology. PhD. dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Odling–Smee FJ, Laland KN, Feldman MW. Niche Construction: The Neglected Process in Evolution. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown MJ. In: Explaining Culture Scientifically. Brown MJ, editor. Seattle: Univ Washington Press; 2008. pp. 162–183. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durham WH. In: Explaining Culture Scientifically. Brown MJ, editor. Seattle: Univ Washington Press; 2008. pp. 139–61. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsons T. The Social System. Glencoe, IL: Free Press; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radcliffe–Brown AR. Structure and Function in Primitive Society. New York: Free Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nadel SF. The Foundations of Social Anthropology. New York: Free Press; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geertz C. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strauss C. In: Motives and Cultural Models. D'Andrade R, Strauss C, editors. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge Univ Press; 1992. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 16.D'Andrade R. In: Explaining Culture Scientifically. Brown MJ, editor. Seattle: Univ Washington Press; 2008. pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sperber D. Explaining Culture: A Naturalistic Approach. Oxford: Blackwell; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gates H. China's Motor: A Thousand Years of Petty Capitalism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomasello M, Carpenter M, Call J, Behne T, Moll H. Understanding and sharing intentions: The origins of cultural cognition. Behav Brain Sci. 2005;28:675–735. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cavalli–Sforza LL, Feldman MW. Cultural Transmission and Evolution: A Quantitative Approach. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyd R, Richerson PJ. Culture and the Evolutionary Process. Chicago: Univ Chicago Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durham WH. Coevolution: Genes, Culture, and Human Diversity. Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ihara Y, Feldman MW. Cultural niche construction and the evolution of small family size. Theor Popul Biol. 2004;65:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.tpb.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harrell S. Modes of belief in Chinese folk religion. J Sci Stud Relig. 1977;16:55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goffman E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gates H. In: Chinese Families in the Post-Mao Era. Davis D, Harrell S, editors. Berkeley, CA: Univ California Press; 1993. pp. 251–274. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipatov M, Brown MJ, Feldman MW. Human Social and Cultural Niche Construction in Taiwan: Modeling Changes in Belief and Marriage Form. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0303. forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolf AP, Huang CS. Marriage and Adoption in China, 1845–1945. Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gould SJ, Vrba E. Exaptation—A missing term in the science of form. Paleobiology. 1982;8:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown MJ. Ethnic identity, cultural variation and processes of change: Rethinking the insights of standardization and orthopraxy. Mod China. 2007;33:91–124. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laitin DD. Nations, States, and Violence. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.D'Andrade R. The Development of Cognitive Anthropology. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge Univ Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strauss C. In: Human Motives and Cultural Models. D'Andrade R, Strauss C, editors. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge Univ Press; 1992b. pp. 197–224. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Astuti R, Harris PL. Understanding mortality and the life of the ancestors in rural Madagascar. Cog Sci. 2008;32:713–740. doi: 10.1080/03640210802066907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Astuti R. Are we all natural dualists? A cognitive developmental approach. J R Anthropol Inst. 2001;7:429–447. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borofsky R. In: Explaining Culture Scientifically. Brown MJ, editor. Seattle: Univ Washington Press; 2003. pp. 275–296. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown MJ. The cultural impact of gendered social roles and ethnicity: Changing religious practices in Taiwan. J Anthropol Res. 2003;59:47–67. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown MJ. Is Taiwan Chinese? The Impact of Culture, Power, and Migration on Changing Identities. Berkeley, CA: Univ California Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gellner E. The Concept of Kinship and Other Essays. Oxford: Blackwell; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolf AP. In: Explaining Culture Scientifically. Brown MJ, editor. Seattle: Univ Washington Press; 2008. pp. 232–252. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolf M. Women and the Family in Rural Taiwan. Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ko D. Cinderella's Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding. Berkeley, CA: Univ California Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gates H. Bound feet: How sexy were they? Hist Family. 2008;13:58–70. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gates H. Footloose in Fujian: Economic correlates of footbinding. Comp Stud Soc Hist. 2001;43:130–148. doi: 10.1017/s0010417501003619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.