Abstract

The Drosophila lymph gland, the source of adult hemocytes, is established by mid-embryogenesis. During larval stages, a pool of pluripotent hemocyte precursors differentiate into hemocytes that are released into circulation upon metamorphosis or in respon to immune challenge. This process is controlled by the posterior signaling center (PSC), which is reminiscent of the vertebrate hematopoietic stem cell niche. Using lineage analysis, we identified bona fide hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the lymph glands of embryos and young larvae, which give rise to a hematopoietic lineage. These lymph glands also contain pluripotent precursor cells that undergo a limited number of mitotic divisions and differentiate. We further find that the conserved factor Zfrp8/PDCD2 is essential for the maintenance of the HSCs, but dispensable for their daughter cells, the pluripotent precursors. Zfrp8/PDCD2 is likely to have similar functions in hematopoietic stem cell maintenance in vertebrates.

Keywords: Hematopoiesis, Stem cells, Zfrp8/PDCD2, Lineage analysis, Somatic clones, Drosophila

INTRODUCTION

Stem cells are found in most if not all multi-cellular organisms. They have the capacity to self-renew and to give rise to a cell lineage that ultimately forms a diversity of cell types. Stem cells are found in direct contact with a niche made up of cells that signal to the stem cells and control their asymmetric divisions. A primary example is vertebrate hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) residing in the bone marrow niche, which give rise to different blood cells throughout the life of an animal. Many similarities between vertebrate and fly hematopoiesis have been established and the existence of HSCs in Drosophila has been postulated, but never demonstrated (Evans and Banerjee, 2003; Jung et al., 2005; Krzemien et al., 2007; Mandal et al., 2007; Meister and Lagueux, 2003; Sinenko et al., 2009).

The difference between a stem cell and a non-stem cell can be ascertained experimentally by marking a single cell; for instance, by inducing a recombination event during mitosis, and by following the development of the marked cell (Fox et al., 2008; Harrison and Perrimon, 1993; Lee and Luo, 2001; Margolis and Spradling, 1995). A stem cell will give rise to a persistent clone because it maintains its ability to replenish the population of pluripotent daughter cells. A clone induced in a non-stem cell will be transient. The marked cell will divide, and all marked cells will ultimately mature into differentiated cells and will be lost from the population of precursor cells (Fox et al., 2008; Margolis and Spradling, 1995).

Similar to vertebrate hematopoiesis, Drosophila blood cell development occurs in two phases. In the first, ‘primitive’ phase, hemocytes develop from the early embryo head mesoderm and supply the pool of circulating blood cells (de Velasco et al., 2006; Tepass et al., 1994; Wood and Jacinto, 2007). The second phase gives rise to adult hemocytes, produced in a small organ, the lymph gland. The larval lymph gland and the differentiation of hemocytes have been studied using a range of cell-specific markers (Jung et al., 2005; Krzemien et al., 2007; Kurucz et al., 2007; Mandal et al., 2007; Sinenko et al., 2009). The primary, largest lobe of the larval lymph gland is sub-divided into the posterior signaling center (PSC), the medullary zone (MZ) and the cortical zone (CZ; see Fig. 1H). The MZ has been thought to contain a relatively uniform population of pluripotent prohemocytes (PH), sometimes called stem-like cells (Jung et al., 2005; Sinenko et al., 2009). These cells migrate into the CZ as they differentiate into plasmatocytes (PM), crystal cells (CC) and lamellocytes (LM) (Jung et al., 2005). The homeostasis between prohemocytes and differentiated blood cells is maintained by the PSC (Krzemien et al., 2007; Mandal et al., 2007).

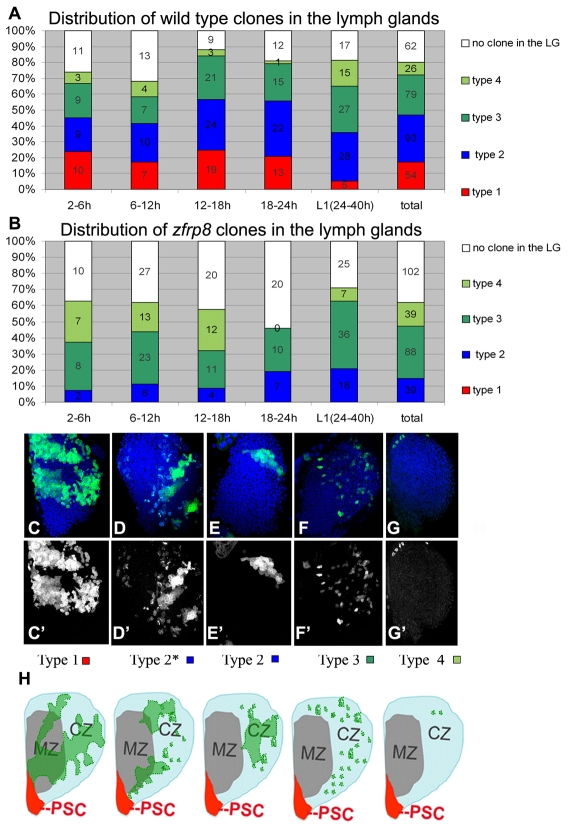

Fig. 1.

Four types of clones are identified in wild-type third instar larval lymph glands. (A) Wild-type clones. Proportion of MARCM clones generated at different time points after fertilization. Numbers of glands with each clone type and glands from mosaic animals with no clones are shown. Percentage (y axis) and numbers of each clone type (on column) are indicated. (B) Zfrp8 mutant clones. No type 1 clones are detected, and the percentage of type 2 clones is reduced. (C-G′) Confocal projections of mid-third instar lymph glands. (C,C′) Type 1 are cohesive clones, typically stretching from the medulla into the cortex and across all or some of the three to four cell layers (see intensity of GFP), occupying 10-30% of the lobe. (D-E′) Two examples of mixed population type 2 clones, located in different parts of the lymph gland, encompassing 4-8% of the lobe. (F,F′) Type 3 clones mainly consist of cells scattered in the cortex. (G,G′) Type 4 clones consist of one to eight cells, always in the cortex. (H) Schematics of third instar larval lymph gland primary lobes with different types of typical clones (green), based on multiple clones. (For more information, see Fig. 2.) PSC, posterior signaling center (red); MZ, medullary zone (gray); CZ, cortical zone (light blue).

The signaling pathways regulating fly blood development involve orthologs of proteins functioning in vertebrate hematopoiesis (Evans and Banerjee, 2003; Hartenstein, 2006; Krzemien et al., 2007; Mandal et al., 2007). Mutations in these conserved genes often alter the larval hemocyte differentiation program and the immune response. Until recently the genes affecting lymph gland development from the embryo onward remained largely unexplored owing to their pleiotropic effects and early lethality. Now novel clonal and RNAi approaches allow the exploration and characterization of the function of such genes specifically in hematopoiesis.

To investigate the existence of stem cells in the Drosophila lymph gland, we induced clones in embryos and first instar larvae, using the MARCM technique combined with UAS-GFP reporters (Lee and Luo, 2001). This technique results in marking a single cell and its progeny, and revealed that in wild-type lymph glands both persistent and transient clones are induced, indicating the presence of hematopoietic stem cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clonal analysis

Clones were generated either by the MARCM or the FRT/FLP techniques. In both cases, mitotic clones were induced by heat-shock at 38°C for 1 hour at the indicated time points. Third instar larval lymph glands were dissected and stained. Wild-type clones were induced in y w hsFLP Tub-GAL4 UAS-GFP:myc-nls/(+ or Y); FRTG13 tubP-GAL80/FRTG13 UAS-mCD8-GFP (WT), and mutant clones in y w hsFLP Tub-GAL4 UAS-GFP:myc-nls/(+ or Y); FRTG13 tubP-GAL80/FRTG13 UAS-mCD8-GFP Zfrp8Df(2R)SM206 (Zfrp8) animals. Zfrp8Df(2R)SM206 was previously described by Minakhina et al. (Minakhina et al., 2007). MARCM, and GFP stocks were obtained from Ken Irvine (Rutgers University) and the Bloomington Stock Center. To verify that clones were generated from one progenitor cell, we performed control experiments with shorter heat-shock times (15 and 30 minutes). Under both conditions, all four types of clones were observed, but the frequencies were three to five times reduced. In control lymph glands, without heat-shock treatment, there was a low incidence of MARCM clones (about one clone per 50 animals), which should not have significantly affected the results.

Immunochemistry and imaging

Embryos and larval lymph glands were dissected, fixed, immunostained and analyzed as described (Jung et al., 2005; Minakhina et al., 2007). Antibodies specific for lamellocytes (L1) and for plasmatocytes (P1) were obtained from Dr I. Ando (Biological Research Center, Szeged, Hungary) and used at 1:400 dilution; rabbit anti-PPO2 antibody from George Christophides (Imperial College, London, 1:2000), rabbit anti-Pxn antibody from John Fessler and Sergey Sinenko (UCLA, 1:700), and anti-Antp antibody from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (Glicksman and Brower, DSHB, 1:20) were used as CC, PH and PSC markers, respectively. Samples were examined with a Zeiss Axioplan-2 microscope. Images were captured using a Leica DM IRBE laser scanning confocal microscope (objectives 40× and 63× oil), analyzed with Leica Microsystems software and further processed using Adobe PhotoShop.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Because stem cells usually represent only a small fraction of the cells in an organ, they are difficult to identify and study. We chose to use the MARCM technique because it marks cells undergoing mitosis, such as stem cells, which are particularly active in young animals. Clones were produced at four embryonic stages, 2-6 hours, 6-12 hours, 12-18 hours and 18-24 hours, and in first instar larvae, by exposing animals to 38°C for one hour to activate the heat-inducible FLP-recombinase (see Materials and methods). 2-6 hour embryos contain about nine precursor cells that will form one lymph gland lobe and the cardioblasts (Mandal et al., 2004). In 6-12 hour embryos, a lymph gland lobe contains about 12 cells, and at stage 16, 20-25 cells. By late first instar larval stage cells have undergone, on average, one additional division (Sinenko et al., 2009). In the absence of infection, hemocytes remain in the lymph gland until metamorphosis when they are released into circulation. This aspect of hemocyte development allowed us to follow wild-type and Zfrp8 clones from the embryo to the third instar larval stage by noting the distribution of marked cells in the lymph glands. As expected, wild-type and mutant PSC clones were obtained with similar frequency (about 6-9%) after induction between 6-18 hours. They had comparable phenotypes and did not mix with non-PSC hemocytes (Jung et al., 2005; Mandal et al., 2007).

Except for the cells in the PSC, the hemocyte precursors within the embryonic lymph glands appear identical and were therefore expected to have similar lineage potential, and to produce clones of comparable size and appearance. However, we recovered a large variety of non-PSC clones that we subdivided into four types according to their size, shape and location (Fig. 1C-H; Fig. 2). Type 1 are large clones encompassing 10-30% of all of the lymph gland cells that form cohesive clusters (Fig. 1C,C′,H; Fig. 2A-C). They occupy a large part of the medulla and extend into the cortex, where they scatter into secondary small clusters. All ten type 1 clones that we stained with the PSC marker Antp contained cells, probably the founder cells, and were in immediate contact with the PSC (Fig. 2C). The frequency of type 1 clones remained about the same (18-29%) independent of when they were induced during embryogenesis. But their frequency was strongly reduced when the clones were induced in first instar larvae.

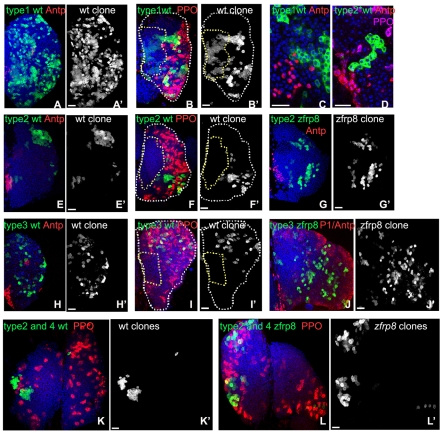

Fig. 2.

Distribution of wild-type and Zfrp8 mutant lymph gland clones. (A,A′) The largest type 1 clones generated in early embryogenesis (2-6 hours) might be derived from a primordial cell. (B-C) Type 1 clones characteristically originate in the central part of the medulla (outlined with yellow dotted line) and extend into the cortex (between yellow and white dotted lines). (C,D) All type 1 clones investigated (10/10) and some of the type 2 clones (4/10) contain cells that are in immediate contact with the PSC. (E-G′) The majority of wild-type and mutant type 2 clones are located in the cortex, but can also be found in medullar cells next to the cortex. (H-J′) Wild-type and Zfrp8 mutant type 3 clones develop scattered patterns in the cortical zone of mid-(H,H′) and late (I-J′) third instar glands. (K-L′) Type 2 and 4 wild-type and Zfrp8 clones in the two lobes of one lymph gland. Clones are shown in green, PSC is marked by nuclear Antp staining (A,C-E,G,H,J, red), and the cortical zone is marked by membrane P1 (J, red), and cytoplasmic PPO staining (B,F,I,K,L, red). Scale bars: 20 μm.

Type 2 was the most heterogeneous class of clones (Fig. 1D-E′,H; Fig. 2E-G′). It included clones encompassing 4-8% of lymph gland hemocytes subdivided into clusters of 20 to 100 cells each. Some clones were partially located in the medullary zone (Fig. 2D,E,G), while most formed islands of hemocytes in the cortical zone (Fig. 2F). Type 3 clones contained only dispersed cells, mostly in the cortex (Fig. 1F,F′,H; Fig. 2H-J′). Some of the cells were in small clusters of two to 12 cells. Type 4 clones were very small, included one to eight cells and were found exclusively in the cortex (Fig. 1G,G′,H; Fig. 2K-L′).

Type 1 clones showed the characteristics of ‘persistent’ clones that are expected when the clone is induced in HSCs or their precursors (primordial cells; see Fig. 2A, Fig. 3C). Founder cells in these clones were in contact with the PSC hematopoietic niche (Fig. 2C), they could self-renew and were pluripotent, meaning that they could differentiate into plasmatocytes, crystal cells and probably lamellocytes (there are too few lamellocytes in a normal lymph gland to establish this positively; Figs 2, 3) (Jung et al., 2005; Mandal et al., 2007). By contrast, type 3 and 4 clones clearly arose from cells that have no self-renewal properties, cells that divide, migrate into the cortex, and differentiate. Because these cells are gradually removed from the medulla, we consider type 3 and 4 clones to be ‘transient,’ as per the nomenclature of Fox et al. (Fox et al., 2008). The types of clones obtained are consistent with the existence of stem cells that can self-renew and replenish the population of pluripotent hemocyte precursors, while their daughter cells divide several times and commit to differentiation. The four types of clones also indicate that the hematopoietic lineage contains at least three developmental stages in addition to the stem cells. All persistent and most transient clones consisted of one or several contiguous patches and scattered cells, indicating that cell mixing was prevalent, especially when cells moved into the cortex.

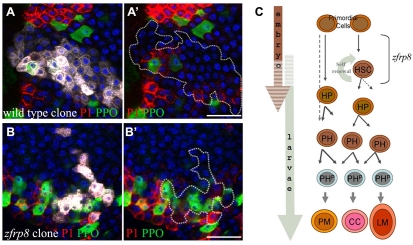

Fig. 3.

Lack of Zfrp8 affects HSCs but not prohemocyte pluripotency. (A-B′) Confocal crossections of wild-type (A,A′) and Zfrp8 mutant (B,B′) clones (white in A,B; outlined in A′,B′) encompassing prohemocytes (no marker), plasmatocytes (P1, red) and crystal cells (PPO, green). Scale bars: 20 μm. (C) Hematopoiesis in the Drosophila lymph gland. During embryogenesis primordial cells form hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and hemocyte precursors (HP). HSCs undergo an asymmetric division, self renewing and giving rise to HPs, which undergo a number of mitotic divisions, migrate towards cortex and undergo gradual differentiation (Jung et al., 2005; Mandal et al., 2007). We call committed cells at intermediate stages of differentiation prohemocytes (PHs). Advanced PHs (PHP) express the early cortical marker Pxn, and during the third instar larval stage differentiate into plasmatocytes (PM), crystal cells (CC) and lamellocytes (LM). Zfrp8 functions in HSC maintenance.

All four types of clones were observed in wild-type glands, independently of when the clones were induced, suggesting that already at the earliest embryonic stage the lymph gland cells have different developmental potentials (Figs 1, 2 and 3), and that all cell types persist at least through the first larval instar. These observations suggest that some of the primordial cells do not form stem cells but undergo differentiation similar to what is observed in the ovary, where some prestem cells fail to form stem cells and instead undergo differentiation (King, 1970). The proportion of type 1 clones was significantly lower in first instar larvae than in early embyos, indicating that the number of stem cells stays relatively constant while their daughter cells multiply. Stem cells are likely to be present still in later larval stages, but they would be difficult to detect because of their relatively low numbers and because their mitotic activity may be reduced. Furthermore, if clones were induced in second and third instar larvae, the short time between the induction of the clones and their analysis would not be sufficient to see a clear difference beween persistent and transient clones.

Our results show that embryonic and first instar larval lymph glands contained HSCs (type 1 clones), transient pluripotent progenitors (type 2 and 3 clones), and cells with limited mitotic potential (type 4). The presence of HSCs in wild-type glands was further validated by the fact that these cells were lost in the absence of Zfrp8.

Zfrp8, also called PDCD2, is highly conserved from flies to humans, and its molecular and physiological function is generally not well understood. Loss of Zfrp8 causes a unique phenotype in Drosophila. The lymph gland is enlarged already in mid-embryogenesis and by the late third instar larval stage, the lymph gland size is increased 10 to 50 times, accompanied by lamellocyte overproliferation (Minakhina et al., 2007).

To study the function of Zfrp8 throughout hematopoiesis, we induced GFP-labeled homozygous mutant Zfrp8 clones in Zfrp8 heterozygous animals (Materials and methods). Analysis of the Zfrp8 mutant lymph gland clones showed that their occurrence differed remarkably from that of wild type. The most striking result was that no type 1 (HSC) clones were detected. The percentage of type 2 clones was reduced, whereas that of type 3 and 4 clones was increased, especially when induced in young embryos. The percentage of mosaic animals with no lymph gland clones was double that of wild type.

In spite of this shift, the phenotypes of type 2, 3 and 4 clones were indistinguishable from that of wild type (Fig. 2E-L′). Lack of Zfrp8 did not result in hemocyte or lamellocyte overproliferation within the clone. The pluripotency of Zfrp8 mutant prohemocytes was the same as that of wild-type cells (Fig. 3A-B′), indicating that Zfrp8 is not required in cells that give rise to transient clones. A similar result was found in other tissues where the clonal loss of Zfrp8 resulted in cells that looked indistinguishable from their wild-type neighbors. Cell proliferation, viability or differentiation was not affected (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material; data not shown).

The absence of persistent clones, the decrease of animals with clones in the lymph gland, the increase of type 3 and 4 clones in young animals, and the absence of a phenotype within the clones, all suggest that Zfrp8 is required specifically in stem cells. Stem cells lacking Zfrp8 loose their ability to self-renew and instead behave like more mature prohemocytes.

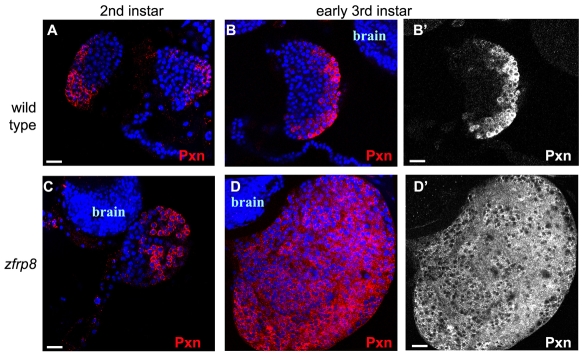

To ascertain whether the Zfrp8 mutant phenotype was consistent with the loss of HSCs, we examined mutant lymph gland growth and hemocyte differentiation during several stages of larval development. Peroxidasin (Pxn) is an early cortex marker expressed in cells committed to differentiation (Jung et al., 2005; Nelson et al., 1994; Sinenko et al., 2009). As in wild type, in second instar mutant glands we detected Pxn-negative cells in the medulla and positive cells in the cortex (Fig. 4,A,C), indicating that these Zfrp8 mutant glands contain hemocyte precursors and prohemocytes (HP and PH in Fig. 3C). But in early third instar mutant larvae, all lymph gland cells had become Pxn-positive (PHP, Fig. 3C), indicating that all hemocyte precursor cells, normally present in the medulla, had matured (Fig. 4D,D′). The absence of hemocyte precursors is consistent with our finding that HSCs, which would replenish this hemocyte population throughout development, were missing in Zfrp8 mutant lymph glands. Thus, the lack of Zfrp8 explains the absence of HSCs and the subsequent loss of the medulla. Larvae without a PSC also lack medulla. The overlap of these two phenotypes is consistent with the PSC controlling the development of the HSCs (Krzemien et al., 2007; Mandal et al., 2007). Conversely, the massive Zfrp8 mutant hemocyte overgrowth was not seen in animals without a PSC, which indicates the existence of an additional signal, possibly also originating in the PSC, that controls hemocyte proliferation and differentiation.

Fig. 4.

Hemocyte differentiation in lymph glands. Wild-type (A-B′) and Zfrp8 mutant (C-D′) lymph glands. Pxn (red) is expressed in the cortex of wild type (A) and Zfrp8 mutant (C) second instar lymph glands. The medulla of wild-type glands (A-B′) is defined by the absence of Pxn, whereas the cortex shows a sharp gradient of staining. Zfrp8 mutants show relatively normal Pxn staining in second instar lymph glands (C,C′) and rapid loss of medulla cells in early third instar glands (D,D′), where virtually all cells are Pxn-positive (note shallow gradient of staining attaining inner cortex levels of wild type). Scale bars: 20 μm.

We have found evidence for a Drosophila hematopoietic lineage established by a stem cell and, further, that the identity of the HCS is dependent on the function of Zfrp8 (Fig. 3C). It is possible that the Zfrp8 human homolog, the PDCD2 protein, has a similar function. PDCD2 is more highly expressed in a CD34+ bone marrow fraction, enriched in HSCs, than in a sample of total bone marrow cells (our unpublished data). Consistent with this observation, transcriptional profiling of mouse embryonic, neural and hematopoietic stem cells showed an enrichment of PDCD2 mRNA in all three stem cells (Ramalho-Santos et al., 2002).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Girish Deshpande, Cordelia Rauskolb, Trudi Schupbach and Abram Gabriel for reading the manuscript, and Istvan Ando, Sergey Sinenko and Kenneth Irvine for fly stocks and antibodies. This work was supported by grants from the New Jersey Commission on Cancer Research (NJCCR) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH; NIHD018055), and by the Goldsmith Foundation. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Footnotes

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.043943/-/DC1

References

- de Velasco B., Mandal L., Mkrtchyan M., Hartenstein V. (2006). Subdivision and developmental fate of the head mesoderm in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Genes Evol. 216, 39-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans C. J., Banerjee U. (2003). Transcriptional regulation of hematopoiesis in Drosophila. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 30, 223-228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox D., Morris L., Nystul T., Spradling A. C. (2008). Lineage analysis of stem cells. In Stem Book (ed. Girard L.). Initiative in Innovative Computing at Harvard University in collaboration with the Harvard Stem Cell Institute; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison D. A., Perrimon N. (1993). Simple and efficient generation of marked clones in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 3, 424-433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartenstein V. (2006). Blood cells and blood cell development in the animal kingdom. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 677-712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S. H., Evans C. J., Uemura C., Banerjee U. (2005). The Drosophila lymph gland as a developmental model of hematopoiesis. Development 132, 2521-2533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King R. C. (1970). Ovarian development in Drosophila melanogaster New York: Academic Press; [Google Scholar]

- Krzemien J., Dubois L., Makki R., Meister M., Vincent A., Crozatier M. (2007). Control of blood cell homeostasis in Drosophila larvae by the posterior signalling centre. Nature 446, 325-328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurucz E., Vaczi B., Markus R., Laurinyecz B., Vilmos P., Zsamboki J., Csorba K., Gateff E., Hultmark D., Ando I. (2007). Definition of Drosophila hemocyte subsets by cell-type specific antigens. Acta. Biol. Hung. 58Suppl, 95-111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T., Luo L. (2001). Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) for Drosophila neural development. Trends Neurosci. 24, 251-254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal L., Banerjee U., Hartenstein V. (2004). Evidence for a fruit fly hemangioblast and similarities between lymph-gland hematopoiesis in fruit fly and mammal aorta-gonadal-mesonephros mesoderm. Nat. Genet. 36, 1019-1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal L., Martinez-Agosto J. A., Evans C. J., Hartenstein V., Banerjee U. (2007). A Hedgehog- and Antennapedia-dependent niche maintains Drosophila haematopoietic precursors. Nature 446, 320-324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis J., Spradling A. (1995). Identification and behavior of epithelial stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Development 121, 3797-3807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister M., Lagueux M. (2003). Drosophila blood cells. Cell Microbiol. 5, 573-580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakhina S., Druzhinina M., Steward R. (2007). Zfrp8, the Drosophila ortholog of PDCD2, functions in lymph gland development and controls cell proliferation. Development 134, 2387-2396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R. E., Fessler L. I., Takagi Y., Blumberg B., Keene D. R., Olson P. F., Parker C. G., Fessler J. H. (1994). Peroxidasin: a novel enzyme-matrix protein of Drosophila development. EMBO J. 13, 3438-3447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho-Santos M., Yoon S., Matsuzaki Y., Mulligan R. C., Melton D. A. (2002). “Stemness”: transcriptional profiling of embryonic and adult stem cells. Science 298, 597-600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinenko S. A., Mandal L., Martinez-Agosto J. A., Banerjee U. (2009). Dual role of wingless signaling in stem-like hematopoietic precursor maintenance in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 16, 756-763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepass U., Fessler L. I., Aziz A., Hartenstein V. (1994). Embryonic origin of hemocytes and their relationship to cell death in Drosophila. Development 120, 1829-1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood W., Jacinto A. (2007). Drosophila melanogaster embryonic haemocytes: masters of multitasking. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 542-551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.