Abstract

The present study examined the relationships between ethnicity, peer-reported bullying and victimization, and whether these relationships were moderated by the ethnic composition of the school classes. Participants were 2386 adolescents (mean age: 13 years and 10 months; 51.9% boys) from 117 school classes in the Netherlands. Multilevel analyses showed that, after controlling for the ethnic composition of school class, ethnic minority adolescents were less victimized, but did not differ from the ethnic majority group members on bullying. Victimization was more prevalent in ethnically heterogeneous classes. Furthermore, the results revealed that ethnic minority adolescents bully more in ethnically heterogeneous classes. Our findings suggest that, in order to understand bullying and victimization in schools in ethnically diverse cultures, the ethnic background of adolescents and the ethnic composition of school classes should be taken into account.

Keywords: Victimization, Bullying, Ethnicity, Adolescents, Multilevel analyses

The Netherlands have a multi-ethnic population and Dutch politicians encourage ethnic integration and try to stimulate interethnic contacts in several ways. For example, they try to prevent the emergence of schools in which more than 50% of the pupils are from ethnic minorities and try to create school classes that comprise members of different ethnic groups. The question is, however, whether bringing together members of ethnic minorities with the ethnic majority will always result in positive interethnic contacts or whether it contributes to bullying. Bullying is often defined as frequent negative actions by one peer or a group of peers toward another child, who is unable to defend itself. Moreover, bullying involves a real or perceived imbalance in physical or social power (Olweus 1991). Peer bullying and victimization are highly prevalent in the Western and non-Western world. In a large-scale multinational study, Eslea et al. (2003) reported prevalence rates of victimization ranging from 5.2% in Ireland to 25.6% in Italy, whereas prevalence rates of bullying ranged from 2.0% in China to 16.9% in Spain. In the United States, prevalence rates of bullying and victimization seem to be even higher (Seals and Young, 2003). Such prevalence rates are alarming given the relationships of bullying and victimization with various psychosocial problems such as depression and loneliness (see for an overview Hawker and Boulton 2000).

Many studies have reported on antecedents for bullying and victimization, such as self-esteem (e.g., DioGuardi and Theodore 2006; Egan and Perry 1998; Olweus 1993), and social status (e.g., Hodges et al. 1997; Hodges and Perry 1999). Informative as previous research has been, it has not often taken the ethnic backgrounds of the children into account. As Cohen et al. (1990) made clear, ethnicity may function as a status characteristic and can lead to an imbalance of power, especially between members of ethnic minorities on the one hand and ethnic majority group members on the other. Since an imbalance of power is known to be a prerequisite of peer bullying (Olweus 1991), ethnicity may play a role in peer bullying and victimization. Moreover, during adolescence peers become more important and adolescents try to define their identity based on affiliations with similar others (Bellmore et al. 2004; Graham and Juvonen 2002), which makes ethnicity especially relevant. The first aim of the present study was therefore to examine whether being a member of the ethnic minority or the ethnic majority group in society was related to bullying and victimization among adolescents.

Previous studies have yielded mixed findings concerning the relationship between ethnicity and victimization. Although some studies did not find significant relationships between ethnicity and victimization (Seals and Young 2003; Moran et al. 1993; Siann et al. 1994), others reported that members of ethnic minority groups were more victimized than members of ethnic majority groups (Mouttapa et al. 2004; Wolke et al. 2001; Verkuyten and Thijs 2002). In contrast, Hanish and Guerra (2000), Nansel et al. (2001), and Graham and Juvonen (2002) found that ethnic minority group members were less victimized than ethnic majority group members. Earlier research also reported mixed findings for ethnicity and bullying, with some studies reporting non-significant associations (Seals and Young, 2003; Moran et al. 1993; Wolke et al. 2001), while others found that bullying was more prevalent among members of ethnic minority groups than among members of ethnic majority groups (Nansel et al. 2001; Graham and Juvonen 2002).

A possible explanation for these mixed findings on the role of ethnicity may be that the school classes under study differed in ethnic composition, that is, in the proportion of children from ethnic minorities relative to the ethnic majority. Usually, studies have not accounted for class-level variables like the ethnic composition of school classes. However, classes may differ in the occurrences of victimization and bullying. In classes that are ethnically more heterogeneous, ethnicity may be a more visible and important status characteristic. Higher proportions of ethnic minorities might emphasize the status differences and imbalance of power between ethnic minority and ethnic majority group members. Numerical differences in ethnic groups in one’s class might intensify perceptions of “us” versus “them” and disparities between groups (Graham and Juvonen 2002). Such disparities were found to be precursors of interpersonal conflicts (see Hewstone 1989), that might be expressed by bullying. In other words, the ethnic composition of school classes may be related to bullying and victimization. The second aim of the present study was to examine—by means of multilevel analyses—whether the ethnic composition of the school class was related to bullying and victimization.

The ethnic composition of a school class not only may be directly related to bullying and victimization, but also may moderate the relationship between ethnicity and bullying and victimization. With regard to victimization, the “misfit” theory suggests that children who are victimized are often children who in some way do not fit in and deviate from the group norm (Nadeem and Graham 2005). Ethnicity can serve as a characteristic to identify children who do not fit in with the general school class (Jackson et al. 2006). Ethnic minority students in school classes with only a small proportion of ethnic minority classmates might not fit in and can therefore be more at risk of victimization compared to ethnic minorities in school classes with higher proportions of classmates with ethnic minority backgrounds. Similarly, victimization of ethnic majority group members might also depend on the ethnic constellation of the school class. As Verkuyten and Thijs (2002) found, in school classes with low proportions of native Dutch children, the native Dutch children were more often victimized than in school classes with high proportions of native Dutch children. In addition, Hanish and Guerra (2000) showed at a more general level that white children in the United States were more victimized in schools with low proportions of white children than in schools with high proportions of white children.

With regard to bullying, the ethnic composition of the school class could moderate the relationships between ethnicity and bullying in different ways. First, according to the ethnic group competition theory (e.g., Coenders et al. 2004), ethnic majority students feel more threatened by high proportions of ethnic minorities, resulting in more negative attitudes toward minorities. Vervoort et al. (2008) indeed showed that ethnic majority adolescents in school classes with high proportions of ethnic minorities reported more negative attitudes toward ethnic minorities than adolescents in classes with low proportions. Majority group adolescents in classes with high proportions of ethnic minorities might not only report more negative attitudes toward ethnic minorities, but they might also execute more bullying behaviors in order to diminish social threat or acquire social dominance (Hawley et al. 2002; Pellegrini and Long 2002). Bullying may be perceived as an effective means, as it is related to social dominance, especially in early adolescence (Hawley et al. 2002; Pellegrini and Long, 2002). On the other hand, it is also possible that ethnic minorities in classes with a high number of ethnic minority students show more bullying behavior, because they might feel more confident being in a larger group of peers who could collectively challenge the dominant status position of the ethnic majority group. Testing whether and how the ethnic composition of a school class moderated the relationship between ethnicity and bullying and victimization was the third aim of the present study.

Many studies showed that gender is significantly related to bullying and victimization in that boys more often bully and are more often victimized than girls (e.g., Pepler et al. 2008; Scholte et al. 2007). Consequently, the relationships between ethnicity and victimization and bullying might be different for boys and girls too. Since in different ethnic groups different sex roles can exist (Sigal and Nally 2004), gender in one ethnic group might have other effects on bullying and victimization than in the other. Very few studies paid attention to possible interaction effects between gender and ethnicity, only Verkuyten and Thijs (2002) showed that Turkish boys and girls, who have an ethnic minority background in the Netherlands, reported equal levels of victimization, while studies in general showed that boys bully more and are also more victimized (e.g., Pepler et al. 2008; Scholte et al. 2007). Further exploration of possible interaction effects between ethnicity and gender with respect to bullying and victimization seems therefore warranted.

Finally, a study of Verkuyten and Thijs (2002) demonstrated that in the Netherlands school classes with a high proportion of ethnic minorities were often smaller. Turkenburg and Gijsberts (2007) showed that ethnic minorities in the Netherlands are overrepresented in the lower educational levels. As a consequence, we controlled for the number of classmates and educational level in the present study.

In sum, previous studies reported contrasting findings about the relationship between ethnicity on the one hand and bullying and victimization on the other. This might be due to the fact that most studies did not account for factors on the level of the classroom or did not make use of multilevel analyses. This is important, since in addition to the direct relationships between ethnicity and bullying and victimization, also direct and moderating effects of ethnic composition of school classes might be at work. Interactions between ethnicity and gender may also play an additional role in the explanation of bullying and victimization levels. Moreover, studies often used different informants to measure bullying and victimization. Most studies relied on self-reports, which seem to reflect the more subjective experience of one individual. Another alternative is the use of peer nominations, which is assumed to be the more objective measure, for it is based on multiple informants. In the present study we examined by means of multilevel analyses whether and how both ethnicity and ethnic composition of school classes were related to bullying and victimization among early adolescents based on peer nominations.

Hypotheses

With regard to victimization, we expected that native Dutch adolescents would be more victimized in classes with high proportions of ethnic minority pupils, and that ethnic minority adolescents would be more victimized in classes with low proportions of ethnic minorities. We also expected the ethnic proportions of school classes to affect frequency of bullying behaviors among ethnic majority and minority students. Finally, we expected boys to bully and be victimized more than girls. Since the present study is one of the first to explore the interactions between ethnicity and gender in relation to bullying and victimization, we did not specify hypotheses concerning the possible interaction effects between ethnicity and gender beforehand.

Method

Participants

The sample of the present study was comprised of 2798 adolescents with a mean age of 13 years and 10 months (SD = 6.77 months) of 117 school classes1 in 43 secondary schools. Of the adolescents, 51.9% were male and 48.1% were female. All adolescents were in the 8th grade (second year of secondary school). With regard to educational levels, 47.9% of the adolescents followed lower vocational or intermediate vocational training (which prepares for secondary vocational education), 19.5% followed high-school education (which prepares for higher professional education) and 32.6% followed pre-university education (which prepares for university).2 Ethnic background was recorded, showing that in the initial sample (n = 2,798) 68.3% of the participants were of Dutch origin (n = 1,911), 17.0% were non-western ethnic minorities (n = 475), 7.5% (n = 209) were western ethnic minorities, and of 203 adolescents (=7.3%) whose ethnic backgrounds were unknown. From the non-western minorities 40.8% were Turkish, 26.9% Moroccan, 9.5% were Surinam, Antillean or Aruban, and 22.7% had a different non-western ethnic background. We focused on the non-western ethnic minorities since these non-western ethnic minorities were more visible and issues of integration and ethnic conflicts in the Netherlands concerned especially these non-western ethnic minority groups. Therefore, the analyses included only native Dutch and non-western ethnic minority adolescents. Attrition analyses (chi-square tests and independent t-tests) showed that the excluded participants did not differ from the other participants in gender, number of classmates, bullying, and victimization. The group excluded from the analyses were, however, in lower educational levels (χ² (2, N = 2731) = 14.16, p < .001) and older (t (397) = 2.53, p < .01) compared to the group of adolescents that was retained for analyses.

Procedure

We randomly selected 38 secondary schools within a range of 100 km from the research institute. Moreover, to ascertain whether the variation in class’ proportions of ethnic minorities was sufficient, we randomly selected five extra secondary schools out of the pre-selected secondary schools with high proportions of ethnic minority pupils, also within a range of 100 km from the research institute. All selected schools received letters through the mail, in which we explained the research project and asked for permission to collect data in some of their classes. All schools were willing to participate in the research project. Consent was also obtained from the adolescents and their parents. The schools gave their students a letter to take home to inform their parents about the study. The parents could contact the research team in case they did not want their child to participate. None of the parents refused participation. After recruitment, the research team visited all participating school classes in November and December 2006 and January 2007 for data collection. During the visits, we asked all the children of the participating classes to fill out questionnaires that included items about ethnicity, bullying, and victimization. Data collection took place in the classrooms during one regular school lesson.

Measures

Ethnicity

To measure ethnicity, the adolescents had to indicate the country of birth of both parents and their own. Answer categories were (1) “The Netherlands”, (2) “Morocco”, (3) “Surinam, Dutch Antilles or Aruba”, (4) “Turkey”, and (5) “Elsewhere, namely…<indicate the country>“. If at least one of the parents was born abroad, the respondent was classified an ethnic minority member, which is the official definition used by Statistics Netherlands (2006a). In addition, we asked to which ethnic group the adolescents assigned themselves. However, this measure appeared to correlate highly with the more “objective” measure of ethnicity (Cramer’s V = .82). Due to this overlap and the higher number of missing cases in the variable on the “subjective” ethnicity, we decided to use the objective definition of ethnicity for the analyses.

Respondents with a western ethnic minority background were excluded from analysis. We used the definition of non-western ethnic minorities from Statistics Netherlands (2006b), which included every adolescent with at least one parent from Turkey or a country in Africa, Latin America or Asia—with the exception of Japan and Indonesia.

Proportion of Ethnic Minorities in Class

The proportion of ethnic minorities in class was calculated by dividing the number of ethnic minority pupils by the total number of adolescents in that class. The proportions ranged from .00 to .91 with a mean of .17 (SD = .18). Proportions of ethnic minorities in school classes were used as dummy variables in the analyses, since preliminary analyses had shown that the linear assumption was violated. To make it possible to examine whether the proportion of .50, the breakpoint of being a numerical majority or minority in class, was especially important in relation to bullying and victimization, we categorized the proportions in quartiles. The dummy variables were a proportion of ethnic minorities in a class of .00–.25 (reference group), a proportion of .25–.50 and a proportion of more than .50. There was no separate dummy variable for the proportion of .75–1.00 since the sample size of this group was too small for analyses (N = 38 pupils).

Bullying and Victimization

Bullying and victimization were assessed using peer nominations, which seems to comprise a more objective measure since it is based on multiple informants (M = 24.3 pupils per school class). The adolescents were provided with a list of names and numbers of their classmates. They were asked to write down the numbers of classmates who best fitted the description given in the items that referred to bullying and victimization. These questions were “Which classmates are being bullied by other classmates?” and “Which classmates bully other classmates?”. Cross-gender nominations were allowed, but self-nominations were not. For each adolescent, the number of received nominations on each of the peer nomination items was calculated. Based on these received nominations, the proportion of victim and bully nominations were calculated for each child (number of nominations divided by number of classmates), which indicated the relative involvement in bullying, either as a perpetrator or a victim. These proportions were converted into standard scores for the entire group and were subsequently used for analysis. As we were interested in differences at the class level, like Jackson et al. (2006), in the present study the scores were not standardized within classrooms, because then there would be no variance between classes.

Data Analysis

All relations between gender, educational levels, number of classmates, and bullying and victimization as well as the interactions between ethnicity and proportions of ethnic minorities and ethnicity by gender were examined using MLwiN (e.g., Rasbash et al., 2000), software for multilevel analyses. A multilevel analytic strategy is most appropriate when testing the roles of both individual-level (i.e., ethnicity, gender, educational level) and class-level variables (i.e., number of classmates, proportion of ethnic minorities in class) than the conventional techniques such as t-tests and regression analyses. A problem of using these conventional techniques when examining classroom effects is that they ignore the hierarchically ordered structures of the data as students are nested in school classes, resulting in standard errors that come out smaller in the analyses than they are likely to be in reality (Lee 2000; see also Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). The advantage of multilevel analyses is that they control for dependencies in the data that are the results of participants sharing the same classroom context. This makes it possible to test individual-level predictors while controlling for variability related to the classroom.

Conducting multilevel analyses thus allowed us to estimate bullying and victimization by student characteristics (gender, ethnicity, educational level), group characteristics (number of classmates, proportion of ethnic minorities), and interactions (ethnicity by proportion of ethnic minorities, ethnicity by gender), taking both the variances between classes and within classes into account. The classroom and school levels would partly overlap since sometimes only one school class participated (N = 38 school classes). Therefore, it was not possible to define a third school level. Moreover, we did not collect any data on the school level. Separate analyses were conducted for bullying and victimization.

Results

Victimization

To study whether and how ethnicity was related to victimization, first an Intercept Only Model was estimated (see Model 1, Table 1). The variance between classes (.02) was significant (p < 001) and explained 2.30% of the total variance in victimization. This means that there were significant differences between school classes in victimization scores, which make multilevel analyses useful. Model 2 (Table 1) included the individual variables gender, educational levels, and ethnicity. Girls were less victimized than boys according to their peers (−.08, p < .05). Adolescents with high-school and pre-university educational levels showed lower victimization scores than adolescents with a low or intermediate education according to their peers (−.15, p < .05; −.27, p < .001). Ethnicity was not directly related to victimization. Differences in these individual variables explained 65.22% of the variance in victimization scores between school classes.

Table 1.

Results of the multilevel analysis for peer-reported victimization scores (unstandardized coefficients). Standard errors in parentheses (N = 2,386)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | .01 (.03) | .18 (.04) | .09 (.04) | .11 (.04) |

| Individual variables | ||||

| Gendera | ||||

| Girl | −.08 (.04)* | −.09 (.04)* | −.13 (.05)* | |

| Educational levelb | ||||

| High-school | −.15 (.06)* | −.02 (.06) | −.02 (.06) | |

| Pre-university | −.27 (.05)*** | −.16 (.05)* | −.16 (.05)** | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Ethnic Minoritiesc | −.08 (.05) | −.20 (.06)*** | −.26 (.09)** | |

| Classroom variables | ||||

| Number of classmates | −.06 (.03)* | −.05 (.03)* | ||

| Proportion of ethnic minoritiesd | ||||

| .25–.50 | .16 (.07)* | .22 (.09)* | ||

| .50< | .35 (.09)*** | .38 (.15)* | ||

| Interactions | ||||

| Ethnicity * .25–.50 | −.18 (.15) | |||

| Ethnicity * .50< | −.08 (.18) | |||

| Ethnicity * gender | .22 (.10)* | |||

| Variance | ||||

| Between classes | .02 (.01) | .01 (.01) | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) |

| (∆ variance) | (65.22) | (100.00) | (100.00) | |

| Between individuals | .98 (.03) | .99 (.03) | .98 (.03) | .98 (.03) |

| (∆ variance) | (.00) | (.00) | (.00) | |

| Df | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| χ² deviance difference | 105.53*** | 26.12*** | 5.91 | |

Notes: * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

aReference group is boy, b reference group is low/intermediate, c reference group is ethnic majority, d reference group is .00–.25; ∆ variance = % explained variance compared to Model 1

The class-level variables were added in Model 3 (Table 1), showing that adolescents in classes with higher numbers of classmates were less victimized (−.06, p < .05). Proportions of ethnic minorities higher than .25 (i.e., .25–.50 and .50 or more) were significantly related to victimization scores (.16, p < .05; .35, p < .001). Adolescents in classes with a proportion of ethnic minorities higher than .25 had significantly higher scores on victimization than adolescents in classes with a proportion of ethnic minorities less than .25. Taking these classroom variables into account, ethnicity also came out as a significant predictor of victimization (−.20, p < .001). Apparently, a suppressor effect was at work here. The relations between ethnicity and victimization were suppressed if the classroom variables were not taken into account. But controlling for variations in the number of classmates and ethnic composition of the school classes, ethnicity thus indeed showed to be significantly related to victimization. Ethnic minorities were less victimized than ethnic majority members. The explained variance of this Model shows that the variance between school classes is 100%. Differences in individual variables, number of classmates, and ethnic composition of school classes seem to explain all the differences in victimization between school classes.

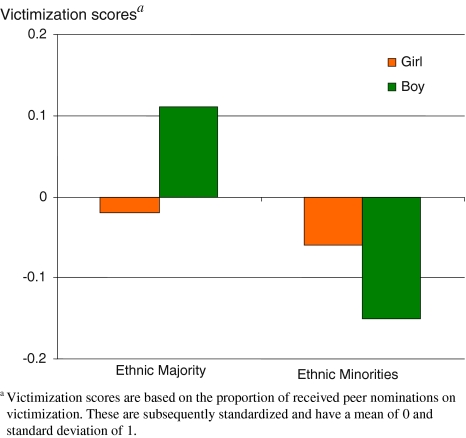

Finally, Model 4 (Table 1) included the interactions between ethnicity and the proportions of ethnic minorities and the interactions between ethnicity and gender. The interaction terms with the proportion of ethnic minorities in class were non-significant. The proportions of ethnic minorities in class did not moderate the relations between ethnicity and victimization. Although ethnic majority group members were more victimized than ethnic minority members in general, ethnic majority group members were not significantly more victimized in classes with higher proportions of ethnic minority pupils compared to ethnic majority group members in classes with low proportions of ethnic minorities. The interactions between ethnicity and gender appeared significant. Figure 1 demonstrates the interactions. The difference in victimization between boys and girls is smaller for ethnic minorities than for the ethnic majority group. Further, the found interaction shows that ethnic majority boys are more victimized than ethnic majority girls, but that ethnic minority girls are more victimized than ethnic minority boys.

Fig. 1.

Victimization scores of ethnic majority and ethnic minorities boys and girls

Bullying

With regard to peer-reported bullying, the Intercept Only Model (see Model 1, Table 2) showed that the variance between classes was .10, which was significant (p < .001). Differences between classes explained 10.24% of the total variance of the bullying scores. Differences between classes explain more of the variance in bullying than they explain of the variance in victimization (which was 2.30%). This means that variables at the class-level are more important in predicting bullying than they are for predicting victimization. Model 2 (Table 2) included the individual variables. Girls had significantly lower scores on bullying than boys (−.53, p < .001). Adolescents with high-school and pre-university educational levels scored significantly lower on bullying than adolescents with low or intermediate educational levels (−.28, p < .001; −.29, p < .001). Ethnicity was also related to bullying (.11, p < .05). Ethnic minorities scored significantly higher on bullying than ethnic majority group members. Differences in these individual variables explained 20.19% of the variance between classes.

Table 2.

Results of the multilevel analysis for peer-reported bullying scores (unstandardized coefficients). Standard errors in parentheses (N = 2,386)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | .04 (.04) | .40 (.05) | .28 (.06) | .29 (.06) |

| Individual variables | ||||

| Gendera | ||||

| Girl | −.53 (.04)*** | −.53 (.04)*** | −.54 (.04)*** | |

| Educational levelb | ||||

| High-school | −.28 (.08)*** | −.10 (.08) | −.11 (.08) | |

| Pre-university | −.29 (.07)*** | −.13 (.08)† | −.14 (.08)† | |

| Ethnicityc | ||||

| Ethnic minorities | .11 (.05)* | .06 (.06) | −.03 (.08) | |

| Classroom variables | ||||

| Number of classmates | −.12 (.03)*** | −.12 (.03)*** | ||

| Proportion of ethnic minoritiesd | ||||

| .25–.50 | .12 (.10) | .04 (.11) | ||

| .50< | .18 (.12) | .16 (.16) | ||

| Interactions | ||||

| Ethnicity * .25–.50 | .25 (.14)† | |||

| Ethnicity * .50< | .07 (.17) | |||

| Ethnicity * gender | .06 (.10) | |||

| Variance | ||||

| Between classes | .10 (.02) | .08 (.02) | .06 (.01) | .06 (.01) |

| (∆ variance) | (20.19) | (41.35) | (41.35) | |

| Between individuals | .91 (.03) | .84 (.03) | .84 (.03) | .84 (.03) |

| (∆ variance) | (8.22) | (8.11) | (8.22) | |

| Df | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| χ² deviance difference | 306.76*** | 19.88*** | 3.63 | |

Notes: † p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

aReference group is boy, b reference group is low/intermediate, c reference group is ethnic majority; d reference group is .00–.25; ∆ variance = % explained variance compared to Model 1

The following model, Model 3 (Table 2), included the classroom level variables, number of classmates, and the proportions of ethnic minorities. The number of classmates was negatively related to bullying, which indicated that adolescents in classes with high numbers of classmates scored lower on bullying (−.12, p < .001). The relations between the proportions of ethnic minorities in class and bullying were not significant. Ethnic minorities and members of the ethnic majority group did not differ in bullying, if number of classmates and proportions of ethnic minorities in class were taken into account. The explained variances showed that by including the classroom variables the model explained 41.35% of the differences between classes in bullying scores.

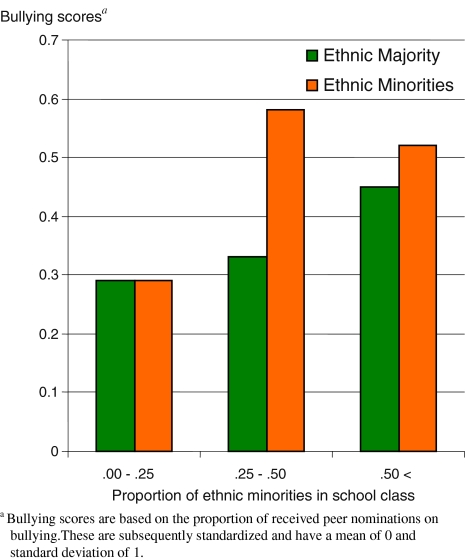

Finally, in Model 4 (Table 2) the interactions between ethnicity and the proportions of ethnic minorities in the class and the interactions between ethnicity and gender were added. The interactions between ethnicity and the proportion of ethnic minorities in classes of .25–.50 were marginally significant (.25, p < .10). Ethnic minority adolescents in classes with a proportion of ethnic minorities of .25–.50 scored higher on bullying than ethnic minorities in classes with a proportion of ethnic minorities less than .25. In line with Holmbeck (2002) we subsequently calculated the formulas for both ethnic minorities and ethnic majority group members for school classes with proportions of ethnic minorities of .00–.25, .25–.50, and <50. Figure 2 demonstrates the interactions. The figure shows that there is no difference in bullying scores between ethnic minorities and ethnic majority group members in classes with a proportion of ethnic minorities in school class of .00–.25, but that ethnic minorities in school classes with a proportion of .25–.50 of ethnic minority classmates clearly have higher bullying scores than the ethnic majority group members in those school classes. The interactions between ethnicity and gender were not significant. The differences between boys and girls in bullying were not significantly different for ethnic minority and majority group members.

Fig. 2.

Bullying scores of ethnic majority and ethnic minorities adolescents in school classes with different proportions of ethnic minorities

Discussion

The present study examined whether ethnicity was related to bullying and victimization in Dutch secondary school classes, taking both the direct and moderating effects of the proportion of ethnic minorities in school classes into account. Our findings reveal that it is indeed necessary to account for the ethnic composition of the school classes if the relationships between ethnicity and bullying and victimization are to be studied.

With regard to victimization, we found that the relationship between ethnicity and victimization only became significant after including the ethnic composition of the school class into the model. Controlling for the ethnic composition of school classes, ethnic minorities were less often victimized than native Dutch classmates. Moreover, the direct effects of the ethnic composition of the school class were significantly related to victimization. School classes in which at least 25% of the classmates were of an ethnic minority background were characterized by higher levels of victimization compared to school classes with fewer ethnic minorities. Although Verkuyten and Thijs (2002) and Hanish and Guerra (2000) did not find a significant relationship between the ethnic composition of the school (classes) and victimization, the results of other studies are in line with our findings. Rowe et al. (1999) showed that the related levels of aggressive behaviors were higher in more ethnic heterogeneous schools and Sampson (1984) found that ethnic heterogeneity in the neighborhood was strongly and positively related to intergroup victimization. The finding that more ethnically heterogeneous classes were related to higher levels of victimization might be explained by the idea that numerical differences in ethnically heterogeneous classes will intensify adolescents’ perceptions of “us” and “them”, disparities between groups (Graham and Juvonen 2002), and status differences, which may result in higher levels of victimization. However, the ethnic composition of school classes did not moderate the relationships between ethnicity and victimization, as could be expected on the basis of the misfit theory (e.g., Nadeem and Graham, 2005). Students who did not “fit in” with the general school class due to their ethnicity were not more often victimized than others. Native Dutch students were more victimized than ethnic minorities in general, but this was not related to the ethnic composition of the school classes. Higher levels of victimization in ethnically heterogeneous classes seem thus not directed at ethnic minorities or native Dutch students in particular.

With regard to bullying, it again became apparent that it was important to take the ethnic composition of school classes into account. Although it first seemed that ethnic minorities bullied more than native Dutch adolescents, this relationship became non-significant after including the number of classmates and the proportion of ethnic minorities in the class. This indicates that the relation between ethnicity and bullying is dependent on the ethnic composition of the school class. The marginally significant interaction effects between ethnicity and the proportion of ethnic minorities in the class of .25–.50 suggest that ethnic minorities in these ethnically heterogeneous classes display more bullying behavior than ethnic minorities in classes with fewer ethnic minority classmates. Related results of Jackson et al. (2006) were in line with our findings. They found that Black children (a minority group in American society) in classes with 34–66% of Black children scored higher on “Fights” than Black children in classes with lower percentages of Black children (0–33%). Ethnic minorities in classes with higher proportions of ethnic minorities might feel more confident to challenge the position of the ethnic majority group and obtain more dominance by means of bullying (Hawley et al. 2002; Pellegrini and Long 2002). However, our findings pointed out that the higher occurrence of bullying of ethnic minorities in these classes was not necessarily directed at ethnic majority group members (i.e., native Dutch adolescents) in particular. However, combining the findings that ethnic minority members were reported to be victimized less often than the ethnic majority group in general and scored higher on bullying in more ethnically heterogeneous classes than ethnic majority members may imply that bullying behavior in classroom settings is at least partly an ingroup-outgroup phenomenon. Furthermore, in more ethnically heterogeneous school classes bullying between students of different ethnic minority groups might also be more likely to occur. Verkuyten et al. (1996) showed that there is a hierarchy in ethnic status within ethnic minority groups in the Netherlands. Students of different ethnic minority groups may therefore also bully each other in more heterogeneous school classes in order to acquire social dominance.

Finally, we also explored whether gender and ethnicity interact in relation to bullying and victimization. Similar to other research (e.g., Pepler et al. 2008; Scholte et al. 2007). we found that in general boys are more victimized and bully more than girls. However, in the present study gender appeared to interact with ethnicity in relation to victimization. In line with Verkuyten and Thijs (2002), our results suggest that the difference between boys and girls in the levels of victimization is smaller for ethnic minorities than for the ethnic majority group. Moreover, ethnic minority girls appeared to be more at risk for victimization than ethnic minority boys.

It is difficult to compare results of existing studies concerning ethnicity and bullying and victimization. While our study highlighted that the relationships between ethnicity and bullying and victimization depended on taking the ethnic composition of school class, a class-level variable, into account, previous studies often did not account for ethnic composition of school classes and did not use multilevel analyses. Our study also showed that the interaction between ethnicity and gender, which most previous studies did not include, play a role in the explanation of victimization. Further, studies differed in the informants (self-reports or peer nominations) used to measure bullying and victimization. Moreover, some studies (e.g., Verkuyten and Thijs 2002) concerned racist victimization, which is not completely comparable with our measurement of general bullying and victimization (see Moran et al. 1993). Furthermore, studies differed in the ethnic groups they included, which made the comparison of results even more difficult, since it can be questioned whether the same relationships are apparent for different ethnic minority groups in different host countries. We need more research to further unravel these relationships with the use of both self and peer-reported measures of general and racist bullying and victimization, and by taking the ethnic composition of school classes and possible interaction effects between ethnicity and gender into account.

Our study has some limitations. A first limitation is that we did not differentiate between different ethnic minority groups due to their small sample sizes. Differentiating might be worthwhile, because of the hierarchy in ethnic status between ethnic minority groups in the Netherlands (Verkuyten et al. 1996), this might play a role in bullying and victimization processes. It can be expected that bullying and victimization not only occur among members of the ethnic majority group and ethnic minorities, but also among members of different ethnic minority groups. In our study, we were not able to test this possibility. To obtain a more detailed description of the significance of ethnicity in bullying or victimization, future research should distinguish between the different ethnic minorities present in society.

A second limitation is that our study only comprised of adolescents in the 8th grade with a mean age of around 14. It has to be examined whether our findings can be generalized to other grades and ages. Nansel et al. (2001) found that the frequency of bullying was higher in grades 6–8 than in the 9th and 10th grade and according to Seals and Young (2003) 7th graders were more involved in bullying than 8th graders. Furthermore, the importance of ethnicity may be different before and after adolescence, since it is expected that ethnicity is especially relevant in the period of adolescence (Bellmore et al. 2004; Graham and Juvonen 2002).

Despite these limitations, our study shows that in today’s societies with increasing numbers of ethnic minorities it is important to be aware of the roles of the students’ ethnicity and the ethnic composition of the school classes when studying peer bullying and victimization. An important implication of our findings is that schools should be aware that ethnicity can play a role in bullying and victimization. Our study suggests that bringing ethnic minorities and ethnic majority group members together in one school class does not automatically lead to positive interethnic contacts. As we found that victimization was more prevalent in more ethnically heterogeneous school classes and ethnic minorities displayed more bullying behaviors in these classes, it may be important to undertake efforts to diminish perceived status differences and disparities among ethnic groups. Moreover, one should find ways to increase opportunities for positive social interactions between members of the ethnic majority and minority groups and intergroup friendships. These friendships are shown to be at least related to less negative attitudes toward other ethnic groups (Pettigrew and Tropp 2006) and might also be related to less perceived status differences between ethnic groups.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Biographies

Miranda H. M. Vervoort

received her Research Master’s degree from the Behavioral Science Institute in 2007 and is currently working on her dissertation at the Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP) and the Interuniversity Center for Social Science Theory and Methodology (ICS). Her major research interests include ethnic concentration, social-cultural integration, interethnic contacts, and interethnic attitudes.

Ron H. J. Scholte

received his Ph.D. in the Social Sciences from the Radboud University of Nijmegen, the Netherlands. He currently works as Assistant Professor at the Behavioral Science Institute of the Radboud University Nijmegen. His areas of interest include social relationships in adolescence, primarily friendships and bullying. In addition, he conducts research on the links between parents, genes, and adolescent substance use.

Geertjan Overbeek

worked on his dissertation, studying the development of internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors in adolescence and young adulthood from 1999 to 2003. Currently, Geertjan Overbeek is an Assistant Professor at the Behavioral Science Institute of the Radboud University Nijmegen. His research interests primarily focus on social-emotional development in adolescence and young adulthood.

Footnotes

In our study, a school class consisted of around 25 pupils of the same educational level with whom they have most of their lessons.

In the Dutch school system, children make the transition to secondary school at an age of around twelve. At this point they have to choose between several levels; VMBO (“low/intermediate vocational level”) prepares pupils for secondary vocational education, HAVO (“high-school”) prepares pupils for higher professional education and VWO (“pre-university”) is the level one needs to go to university (Kuhry et al. 2004). In the first 2 years of secondary education, adolescents spend most of the time in school with their root class.

Contributor Information

Miranda H. M. Vervoort, Phone: +31-704307411, Email: m.vervoort@scp.nl

Ron H. J. Scholte, Phone: +31-243612123, FAX: +31-243612776, Email: r.scholte@bsi.ru.nl

Geertjan Overbeek, Phone: +31-243612123, FAX: +31-243612776, Email: g.overbeek@bsi.ru.nl.

References

- Bellmore AD, Witkow MR, Graham S, Juvonen J. Beyond the individual: The impact of ethnic context and classroom behavioral norms on victims’ adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:1159–1172. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenders M, Gijsberts M, Hagendoorn L, Scheepers P. Introduction: Nationalism and exclusionist reactions. In: Gijsberts M, Hagendoorn L, Scheepers P, editors. Nationalism and exclusion of migrants: Cross-national comparisons. Aldershot: Ashgate; 2004. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen EG, Lotan R, Catanzarite L. Treating status problems in the cooperative classroom. In: Sharan S, editor. Cooperative learning: Theory and research. New York, NY: Praeger Publishers; 1990. pp. 203–229. [Google Scholar]

- DioGuardi RJ, Theodore LA. Understanding and addressing peer victimization among students. In: Jimerson SR, Furlong M, editors. Handbook of school violence and school safety: From research to practice. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2006. pp. 339–352. [Google Scholar]

- Egan SK, Perry DG. Does low self-regard invite victimization? Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:299–309. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eslea M, Menesini E, Morita Y, O’Moore M, Mora-Merchán JA, Pereira B, Smith PK. Friendship and loneliness among bullies and victims: Data from seven countries. Aggressive Behavior. 2003;30:71–83. doi: 10.1002/ab.20006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Juvonen J. Ethnicity, peer harassment, and adjustment in middle school: An exploratory study. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2002;22:173–199. doi: 10.1177/0272431602022002003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Guerra NG. The roles of ethnicity and school context in predicting children’s victimization by peers. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:201–223. doi: 10.1023/A:1005187201519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker DSJ, Boulton MJ. Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analyctic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:441–455. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley PH, Little TD, Pasupathi M. Winning friends and and influencing peers: Strategies of peer influence in late childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2002;26:466–474. doi: 10.1080/01650250143000427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hewstone M. Causal attributions: From collective processes to collective beliefs. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Malone MJ, Perry DG. Individual risk and social risk as interacting determinants of victimization in the peer group. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:1032–1039. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Perry DG. Personal and interpersonal antecedents and consequences of victimization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;67:677–685. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.76.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MF, Barth JM, Powell N, Lochman JE. Classroom contextual effects of race on children’s peer nominations. Child Development. 2006;77:1325–1337. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhry, B., Herweijer, L., & Heesakker, R. (2004). Education. In Social and Cultural Planning Office, Public sector performance: An international comparison of education, health care, law and order and public administration (pp.74–119). The Hague: Social and Cultural Planning Office.

- Lee VE. Using hierarchical linear modeling to study social contexts: The case of school effects. Educational Psychologist. 2000;35:125–141. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3502_6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moran S, Smith PK, Thompson D, Whitney I. Ethnic differences in experiences of bullying: Asian and white children. The British Journal of Educational Psychology. 1993;63:431–440. [Google Scholar]

- Mouttapa M, Valente T, Gallaher P, Rohrbach LA, Unger JB. Social network predictors of bullying and victimization. Adolescence. 2004;39:315–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Graham S. Early puberty, peer victimization and internalizing symptoms in ethnic minority adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2005;25:197–222. doi: 10.1177/0272431604274177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Craig W, Overpeck MD, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviours among U.S. youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;16:2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bully/victim problems among school children: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. In: Pepler D, Rubin K, editors. The development and treatment of childhood aggression. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 411–448. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Victimization by peers: Antecedents and long-term outcomes. In: Rubin KH, Asendorf JB, editors. Social withdrawal, inhibition, and shyness in childhood. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1993. pp. 315–341. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD, Long JA. A longitudinal study of bullying, dominance, and victimization during the transition from primary to secondary school. The British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2002;20:259–2280. doi: 10.1348/026151002166442. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pepler D, Jiang D, Craig W, Connolly J. Developmental trajectories of bullying and associated factors. Child Development. 2008;79:325–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasbash J, Browne W, Goldstein H, Yang M, Plewis I, Healy M, Woodhouse G, Draper D, Langford I, Lewis T. A user’s guide to MLwiN. United Kingdom: Institute of Education; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk SA. Hierarchical linear models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC, Almeida DM, Jacobson KC. School context and genetic influences on aggression in adolescence. Psychological Science. 1999;10:277–280. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. Group size, heterogeneity, and intergroup conflict: A test of Blau’s inequality and heterogeneity. Social Forces. 1984;62:618–639. doi: 10.2307/2578703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scholte RHJ, de Kemp RAT, Haselager GJM, Engels RCME. Longitudinal stability in bullying and victimisation in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:217–238. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9074-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals D, Young J. Bullying and victimization: Prevalence and relationship to gender, grade level, ethnicity, self-esteem, and depression. Adolescence. 2003;38:735–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siann G, Callaghan M, Glissov P, Lockhart R, Rawson L. Who gets bullied? The effect of school, gender and ethnic group. Educational Research. 1994;36:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Sigal J, Nally M. Cultural perspectives on gender. In: Pauludi MA, editor. Praeger guide to the psychology of gender. Westport, CT.US: Prager Publisher/Greenwood Publishing Group; 2004. pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Netherlands. (2006a). Retrieved 12 December 2006 from http://www.cbs.nl/nl-NL/menu/themas/dossiers/allochtonen/methoden/begrippen/default.htm?conceptid=37.

- Statistics Netherlands. (2006b). Retrieved 12 December 2006 from http://www.cbs.nl/nl-NL/menu/themas/dossiers/allochtonen/methoden/begrippen/default.htm?conceptid=1013.

- Turkenburg M, Gijsberts M. Opleidingsniveau en beheersing van de Nederlandse taal. (Educational level and command of Dutch language) In: Dagevos J, Gijsberts M, editors. Jaarrapport Integratie 2007 (Annual Report Integration 2007) The Hague, The Netherlands: Netherlands Institute for Social Research; 2007. pp. 72–101. [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten M, Hagendoorn L, Masson K. The ethnic hierarchy among majority and minority youth in The Netherlands. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1996;26:1104–1118. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1996.tb01127.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten M, Thijs J. Racist victimization among children in The Netherlands: The effect of ethnic group and school. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2002;25:310–331. doi: 10.1080/01419870120109502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort, M. H. M., Scholte, R. H. J., & Scheepers, P. L. H. (2008). The ethnic composition of school class, majority–minority friendships and adolescents’ intergroup attitudes (submitted). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wolke D, Woods S, Stanford K, Schulz H. Bullying and victimization of primary school children in England and Germany: Prevalence and school factors. The British Journal of Psychology. 2001;92:673–696. doi: 10.1348/000712601162419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]