Abstract

Objective

We sought to directly compare the effects of type 1 and type 2 diabetes on post-ischemic neovascularization and evaluate the mechanisms underlying differences between these groups. We tested the hypothesis that type 2 diabetic mice have a greater reduction in eNOS expression, greater increase in oxidative stress, and reduced arteriogenesis and angiogenesis resulting is less complete blood flow recovery than type 1 diabetic mice after induction of hindlimb ischemia.

Methods

Hindlimb ischemia was generated by femoral artery excision in streptozotocin-treated mice (model of type 1 diabetes), in db/db mice (model of type 2 diabetes), and in control (C57BL/6) mice. Dependent variables included markers of arteriogenesis and angiogenesis, as well as eNOS and markers of oxidative stress.

Results

Post-ischemia recovery of hindlimb perfusion was significantly less in type 2 than in type 1 diabetic mice; however, neither diabetic group demonstrated a significant increase in collateral artery diameter or collateral artery angioscore in the ischemic hindlimb. The capillary/myofiber ratio in the gastrocnemius muscle decreased in response to ischemia in control or type 1 diabetic mice, but remained the same in type 2 diabetic mice. Gastrocnemius muscle eNOS expression was lower in type 1 and 2 diabetic mice than in control mice; this expression decreased after induction of ischemia in type 2, but not type 1 diabetic mice. The percentage of endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) in peripheral blood failed to increase in either diabetic group after induction of ischemia, whereas this variable significantly increased in the control group in response to ischemia. EPC eNOS expression decreased after induction of ischemia in type 1, but not type 2 diabetic mice. EPC nitrotyrosine accumulation increased after induction of ischemia in type 2, but not type 1 diabetic mice. EPC migration in response to VEGF was reduced in type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice than in control mice. EPC incorporation into tubular structures was less effective in type 2 diabetic mice. Extensive fatty infiltration was present in ischemic muscle of type 2, but not type 1 diabetic mice.

Conclusion

We conclude that type 2 diabetic mice displayed a significantly less effective response to hindlimb ischemia than type 1 diabetic mice.

Keywords: collateral artery, arteriogenesis, angiogenesis, nitrotyrosine, nitric oxide

Introduction

Vascular dysfunction underlies many of the complications of diabetes mellitus, including peripheral artery disease.1 However, the basis for this dysfunction is dissimilar in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Type 1 diabetes is characterized by hypoinsulinemia and profound hyperglycemia. The latter circumstance is particularly injurious to endothelial cells, which lack the capacity to regulate glucose influx.1 Uncontrolled glucose influx results in activation of protein kinase C, and the accumulation of advanced glycation end products and oxidants within the endothelial cell, processes that instigate endothelial dysfunction.1 In contrast, type 2 diabetes is characterized by insulin resistance, moderate hyperglycemia, and an atherogenic dyslipidemia; consequently, the vascular dysfunction in type 2 diabetes reflects the effects of hypercholesterolemia, and not just hyperglycemia on the endothelium.1–3 This distinction may be relevant in the design of treatments for diabetic vascular disease, such as peripheral artery disease. An important gap in knowledge, however, is the lack of a direct comparison between the effects of type 1 and 2 diabetes on the response to vascular injury, i.e., an assessment carried out by applying the identical experimental paradigm to both types of diabetes.

Assessment of hindlimb hemodynamics following ligation or excision of the common femoral artery is a widely used approach to study post-ischemic perfusion recovery and neovascularization.4 By this means Tamarat et al.5 reported significant compromise in post-ischemic hindlimb flow recovery in streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetic mice, while Emaueli et al.6 described similar findings in the Leprdb/db mouse model oftype 2 diabetes. Methodological differences between these studies, however, preclude their use as instruments to directly compare neovascularization responses between types 1 and 2 diabetes.

Bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) are critical participants in post-ischemic neovascularization.7–9 EPC are mobilized from bone marrow and home to sites of vascular injury where they contribute to arteriogenesis within existing collateral arteries and to angiogenesis within capillary networks. Dysfunction in EPC mobilization and function has been reported in type 1 and 2 diabetes.10–13 Deficiencies in generation of eNOS-derived NO14,15 and an increased level of oxidant stress16,17 have been proposed as mechanisms responsible for EPC dysfunction in diabetes. Again, however, direct comparison of these circumstances between type 1 and 2 diabetes has not been reported.

The aim of this study was to compare the effects of type 1 versus type 2 diabetes on blood flow recovery and neovascularization after induction of severe hindlimb ischemia using streptozotocin-induced hypoinsulinemia as a model of type 1 diabetes and the Leprdb/db mouse as a model of type 2 diabetes. We tested the hypothesis that type 2 diabetic mice have greater reduction in eNOS expression, greater increase in oxidative stress, and reduced arteriogenesis and angiogenesis resulting in less complete blood flow recovery than type 1 diabetic mice after induction of hindlimb ischemia.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and reagents

Streptozotocin, Dil-Ac-LDL, Histopaque 1083, Matrigel, and the monoclonal antibody for smooth muscle actin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Monoclonal antibodies for CD31, eNOS, and nitrotyrosine were obtained from BD Bioscience (San Diego, CA). Monoclonal antibodies for CD34, Flk-1, and CD133 were obtained from eBioscience (San Jose, CA). VEGF was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Oil Red O was obtained from Poly Scientific (Bay Shore, NY).

Experimental animals and procedures

C57BL/6 mice were used as the control group. Type 1 diabetes was generated in 8 week old C57BL/6 mice by intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin (50 mg/Kg daily for 5 days). Streptozotocin generates significant, predictable, and reproducible hypoinsulinemia and profound hyperglycemia within 1 week after the onset of treatment. The Leprdb/db (db/db) mouse, generated on a C57BL/6 background, was used as a model of type 2 diabetes. db/db are deficient in the Ob-Rb leptin receptor, critical in regulation of satiety and hence food intake; consequently, db/db mice become significantly obese. db/db mice fully express a type 2 diabetic phenotype of insulin resistance, moderate hyperglycemia, and dyslipidema by 2 months of age.18,19 All mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), were housed in an environmentally controlled room, and were fed standard chow and water before and during the course of study. The care of mice complied with the National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All protocols were approved by the Committees on Animal Research at the University of California, San Francisco and University of Massachusetts Medical School. Hindlimb ischemia was induced as previously described.20 Briefly, mice were anesthetized using 2% isoflurane and the left femoral artery and its associated branches were isolated, ligated, and excised. The contra-lateral hindlimb served as an internal control within each mouse.

Measurement of hindlimb blood flow

A laser Doppler perfusion imager (Moor Instruments, Ltd., Devon, UK) was used to estimate dermal blood flow in calf and foot. Hindlimb fur was removed by depilatory cream and studies were conducted under 1.5% isoflurane anesthesia. Mice were studied while on a heated surface (37 °C) and in a darkened room to minimize the effects of ambient light and temperature on measurements. Blood flow was expressed as a ratio of the ischemic and non-ischemic hindlimbs.

Measurement of collateral artery enlargement and number

Twenty-eight days after induction of hindlimb ischemia, mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane and a contrast medium was injected into the abdominal aorta through a catheter. Images were taken by a digital X-ray transducer. Two observers independently scored the images by counting the number of vessels that crossed a standardized grid overlying the image. The number of vessels was then divided by the lines of the grid in the area of interest to produce an angioscore. It was not possible to completely blind these measurements because the obesity of the db/db type 2 diabetic mice was obvious on the radiographs.

Measurement of collateral artery diameter

Thigh muscle was harvested 28 days after induction of ischemia and frozen at −80°C in OCT. 10 μM cryosections were prepared and incubated with CD31 and smooth muscle actin antibodies for the identification of endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells, respectively, to identify collateral arteries. Collateral artery diameter was measured using precalibrated microscope scale bars. Three sections were reviewed per animal and collateral diameters were quantified in 5 randomly selected low power (200×) fields per section; the mean value of these measurements was taken as a single data point for each animal.

Measurement of capillary density

Gastrocnemius muscle was harvested 28 days after induction of ischemia and frozen at −80°C in OCT. 10 μM cryosections were prepared and incubated with CD31 antibody to identify endothelial cells. Capillary density was expressed as the ratio of CD31+ cells to myofibers. This measurement was determined in 5 randomly selected low power (200×) fields from each animal, and the average value taken and used as a single data point for each mouse.

Assessment of muscle histology

Tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles were harvested on day 28 after induction of ischemia, weighed, and frozen at −80°C in OCT. 10 μM cryosections were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. To identify adipocytes, some cryosections were fixed in 10% formalin for 10 minutes, stained with oil red O at 60 °C for 8 minutes, and then counterstained briefly with eosin. Five low power (200×) fields were randomly selected on each slide and the degree of necrosis and adipocyte infiltration noted in each.

Measurement of eNOS and nitrotyrosine

Muscle tissue was harvested 7 days after induction of ischemia, whereas EPC were obtained from bone marrow or peripheral blood 7 days after induction of ischemia. Tissue (muscle or EPC) was homogenized in buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1% NP40). Protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to pure nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with antibodies to eNOS, nitrotyrosine, or α-tubulin. Enhanced chemiluminescence detection was used to visualize bands. Band intensity was determined by densitometry. Densitometry data for the eNOS and nitrotyrosine bands were expressed as a ratio to α-tubulin band.

EPC studies

Quantitation of EPC in bone marrow and peripheral blood

Bone marrow and peripheral blood were harvested 7 days after induction of ischemia. Mononuclear cells were isolated by gradient centrifugation using Histopaque 1083. 106 mononuclear cells were incubated for 10 minutes with monoclonal antibodies for CD34, Flk-1, and CD133. Isotype antibodies were used as negative controls. Cells were analyzed on a fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) Calibur Flow Cytometer. Each analysis consisted of 500,000 events. Data were analyzed with FloJo software.

Cultivation of EPC

Bone marrow and peripheral blood were harvested 7 days after induction of ischemia. Mononuclear cells were isolated by gradient centrifugation and cultured on fibronectin-coated plates in endothelial cell basal medium supplemented with endothelial growth medium. After 3 days nonadherent cells were removed by washing plates with PBS. Adherent cells were used for in vitro functional analysis.

Measurement of EPC migration

In vitro migration was evaluated in bone marrow-derived EPCs with the use of a modified Boyden’s chamber. Cell suspensions (5×104 cells per well) were placed in the upper chamber and the lower chamber was filled with medium (control) or medium containing human recombinant VEGF (50ng/ml). The chamber was incubated for 16 hours (37°C). Migration activity was evaluated by counting the number of cells on the lower chamber surface. This count was replicated in 3 high power (400×) fields per chamber. The mean count was determined an taken as an individual data point for each assay.

Measurement of EPC tubular incorporation

Matrigel was thawed and placed in 4 well glass slides at room temperature for 30 minutes to allow solidification. Dil-Ac-LDL labled EPCs (2×104) were co-plated with 4×104 human umbilical vein endothelial cells and incubated at 37 °C for 12 hours. The incorporation of EPCs in tubules was determined in 5 random high power (400×) fields. The mean was determined and taken as an individual data point for each assay.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by one way analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test. Statistical significance was accepted at the 95% level (P <0.05) for all analyses.

Results

Blood glucose and body weight

Blood glucose was measured in all mice prior to the onset of study to confirm a diabetic phenotype. Streptozotocin treated type 1 diabetic mice had a fasting blood glucose of 460 ± 36 mg/dl, while, as anticipated, db/db type 2 mice had a more moderate fasting hyperglycemia of 264 ± 14 mg/dl (m ± sd; P<.05). Fasting glucose in control mice was 112 ± 12 mg/dl (m ± sd, P<.05 vs. type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice). Plasma insulin and serum lipids were not measured because it is well established that streptozotocin induces profound hypoinsulinemia and that the db/db mutation results in insulin resistance and an atherogenic dyslipidemia.18,19 Type 2 diabetic mice were significantly heavier than their type 1 counterparts or control mice (type 2 diabetic mice 52 ± 6 g; type 1 diabetic mice 22 ± 1 g; control mice 24 ± 2 g; m ± sd; P<.05 for type 2 diabetic mice vs. type 1 diabetic mice or control mice).

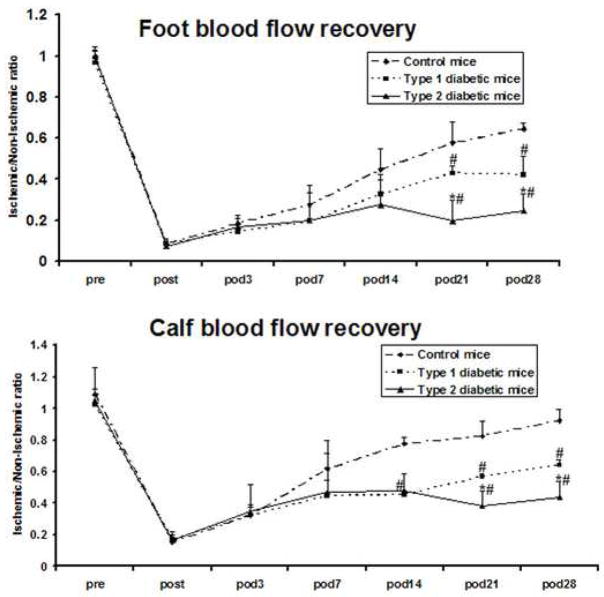

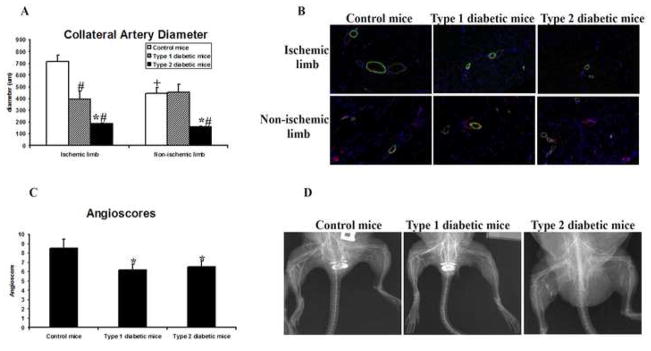

Effect of ischemia on arteriogenesis

Blood flow recovery after induction of severe hindlimb ischemia was significantly less in both type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice than in control mice. In the calf, these differences became significant on day 14 after induction of ischemia, whereas significance was attained on day 21 in the foot (figure 1). Blood flow recovery was thus less complete in type 2 than in type 1 diabetic mice: maximal recovery reached 22% and 43% in the foot and calf, respectively, in type 2 diabetic mice, compared to 42% and 63% in the foot and calf, respectively, in type 1 diabetic mice (P<.05). Type 2 diabetic mice had collateral arteries of significantly smaller diameter in the non-ischemic hindlimb than type 1 diabetic mice or control mice (figure 2A,B). Collateral artery diameter was significantly greater in the ischemic than non-ischemic hindlimb in control mice. In contrast, the collateral artery diameter was similar in the ischemic and non-ischemic hindlimb of type 1 and 2 diabetic mice. Angiography revealed the presence of a well developed collateral artery network in the ischemic thigh of control mice (figure 2C,D). Both type 1 and 2 diabetic mice demonstrated fewer collateral arteries visible on angiography in the ischemic hindlimb and no difference between diabetic groups was observed. Consequently, the angioscores of both diabetic groups were lower than that of the control group.

Figure 1. Blood flow in the calf and foot.

Dermal blood flow in the calf and foot was measured in the same animal at multiple time points before and after induction of ischemia. Flow data represent the ratio of the ischemic to non-ischemic hindlimb. Pre = preoperative; Post = immediately post-operative, POD = post-operative day; m ± sd; n = 5 animals in each group; # P<0.05 type 1 or type 2 diabetic mice vs. control mice; * P<0.05 type 2 diabetic mice vs. type 1 diabetic mice.

Figure 2. Effect of ischemia on collateral arteries.

Studies were undertaken 28 days after the induction of ischemia. (A) Collateral artery diameter in thigh muscles. Collateral artery data are expressed in μM. m ± sd; n = 5 animals in each group; # P<0.05 type 1 or type 2 diabetic mice vs. control mice; * P<0.05 type 2 diabetic mice vs. type diabetic 1 mice; + P<.05 ischemic hindlimb vs. non-ischemic hindlimb. (B) Representative photomicrographs. CD31 is stained red, smooth muscle actin is stained green, and nuclei are stained blue; all photomicrographs were taken at a magnification of 200×. (C) Angioscores. Data represent the number of collateral arteries crossing fixed points on a grid superimposed upon the radiograph. m ± sd; n = 5 animals in each group; * P<0.05 type 1 or type 2 diabetic mice vs. control mice. (D) Representative radiographs.

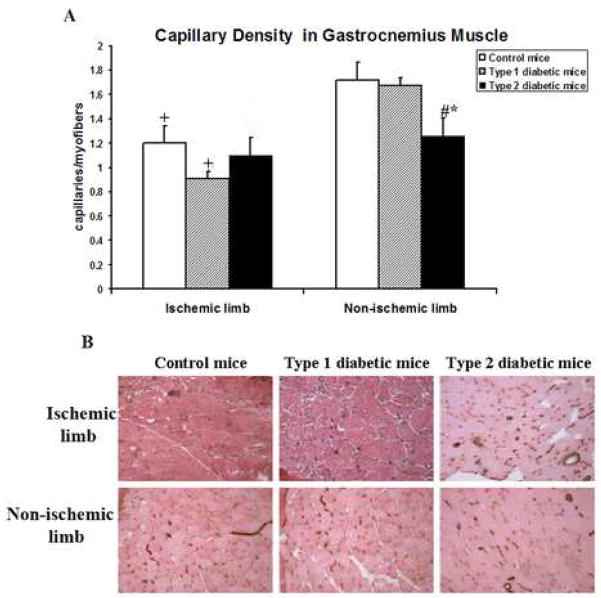

Effect of ischemia on angiogenesis

Capillary density was greater in the ischemic than the non-ischemic hindlimb in control mice (figure 3A,B). A similar pattern was evident in type 1 diabetic mice. In contrast, no difference between the ischemic and non-ischemic limbs was present in type 2 diabetic mice; moreover, the level of capillary density in the non-ischemic hindlimb in this group was less than in either the control group or type 1 diabetic mice.

Figure 3. Effect of ischemia on capillary density.

Studies were undertaken 28 days after the induction of ischemia. (A) Capillary density in gastrocnemius muscle. Data are expressed as the number of C31+ cells per myofiber. m ± sd; n = 5 animals in each group; # P<0.05 type 1 or type 2 diabetic mice vs. control mice; * P<0.05 type 2 diabetic mice vs. type 1 diabetic mice; +P<.05 for ischemic hindlimb vs. non-ischemic hindlimb. (B) Representative photomicrographs. CD31+ cells are stained brown. All photomicrographs were taken at a magnification of 200×.

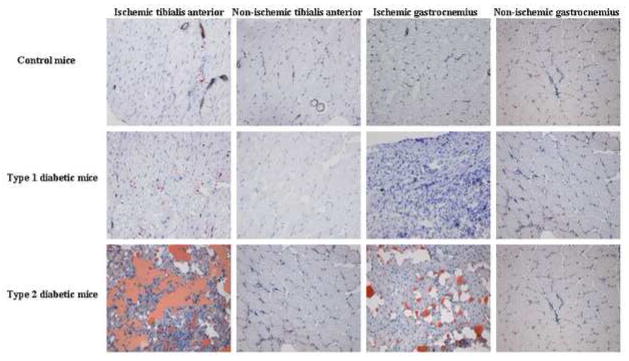

Effect of ischemia on tissue integrity and muscle histology

The rate of incisional wound healing was not different among the 3 study groups; all wounds healed completely by 5–7 days after surgery. No evidence of toe gangrene or digit autoamputation was evident in any study group. Histological evidence of muscle necrosis was evident in the calf muscles from the ischemic hindlimb in all three study groups, as evidenced by the presence of reduced myofiber number and size on H&E staining (not shown). Oil Red O staining revealed extensive fat infiltration in ischemic calf muscles from type 2 diabetic mice. Fat infiltration was never observed in the ischemic hindlimb of control mice and while present, was minimal in the ischemic calf muscles from type 1 diabetic mice (figure 4). Neither fat infiltration nor muscle necrosis was observed in non-ischemic muscles in any group. Weights of the tibialis anterior (TA) and gastrocnemius (GC) muscles from the ischemic hindlimb were different among the three study groups (g): Control, TA 1.04 ± 0.12, GC 0.92 ± 0.15; type 1 diabetes, TA 0.52 ± 0.03*, GC 0.57 ± 0.09*; type 2 diabetes, TA 1.90 ± 0.45*†, GC 1.15 ± 0.14† (m ± sd; *P<.05 type 1 or type 2 diabetic groups vs. control group, †P<.05 type 2 diabetic group vs. type 1 diabetic group). Based on muscle histology, particularly the degree of fat, the greater muscle weight in type 2 diabetic mice was most likely due to fat infiltration rather than skeletal muscle recovery.

Figure 4. Representative oil red O staining of hindlimb muscles.

Muscle was harvested 28 days after induction of ischemia. Fat is stained red by means of Oil Red O; counterstained with hematoxylin. All photomicrographs were taken at a magnification of 200×. These photomicrographs are representative of observations made in 5 animals from each group.

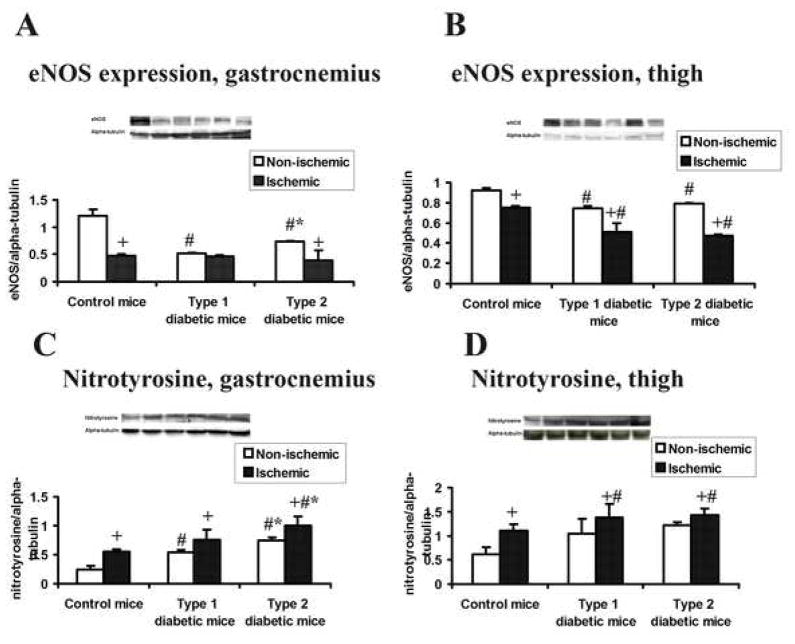

Effect of ischemia on muscle eNOS expression and nitrotyrosine accumulation

eNOS expression in the non-ischemic thigh and gastrocnemius muscles from type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice was less than in control mice (figure 5A,B). Following ischemia, eNOS expression significantly decreased in hindlimb muscles of all three groups, with one exception: expression of eNOS was not significantly different between ischemic and non-ischemic gastrocnemius muscles from type 1 diabetic mice. Nitrotyrosine accumulation was significantly greater in the ischemic than non-ischemic gastrocnemius and thigh muscles in all study groups (figure 5C,D). In the gastrocnemius muscle, nitrotyrosine accumulation was greater in both type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice than in control mice; moreover, nitrotyrosine expression in the ischemic gastrocnemius muscle was greater in type 2 than in type 1 diabetic mice. No differences between diabetic groups were noted in thigh muscles

Figure 5. eNOS and nitrotyrosine expression after induction of ischemia in hindlimb muscle.

Muscle was harvested 28 days after induction of ischemia. m ± sd; n = 3 animals in each group; # P<.05 type 1 or type 2 diabetic mice vs. control mice, * P<.05 type 2 diabetic mice vs. type 1 diabetic mice, + P<.05 ischemic hindlimb vs. non-ischemic hindlimb. Insets present representative western blots; lane designations from left to right: control, non-ischemic hindlimb; control, ischemic hindlimb; type 1 diabetes, ischemic hindlimb; type 1 diabetes, non-ischemic hindlimb; type 2 diabetes, non-ischemic hindlimb; type 2 diabetes, ischemic hindlimb. (A) eNOS expression, gastrocnemius. (B) eNOS expression, thigh muscles. (C) Nitro-tyrosine expression, gastrocnemius. (D) Nitrotyrosine expression, thigh muscles.

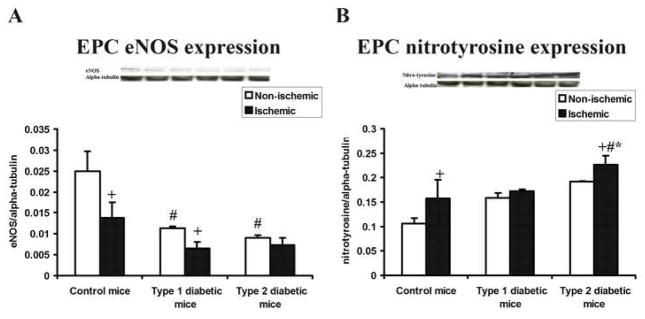

Effect of ischemia on eNOS expression and nitrotyrosine accumulation in bone marrow-derived EPCs

eNOS expression in EPC harvested from the bone marrow from the femur and tibia of the non-ischemic limb was significantly less in type 1 or type 2 diabetic mice than in control mice (figure 6A). In control mice and type 1 diabetic mice, EPCs harvested from the femur and tibia of the ischemic hindlimb demonstrated less eNOS expression than marrow-derived EPC from the non-ischemic hindlimb. In contrast, eNOS expression in marrow-derived EPC from the ischemic hindlimb from type 2 diabetic mice was not different from the relatively low level present in the non-ischemic limb in this group. Nitrotyrosine accumulation was greater in bone marrow-derived EPCs harvested from the ischemic hindlimb in control mice and type 2 diabetic mice. No difference was noted in this variable in type 1 diabetic mice (figure 6B).

Figure 6. eNOS and nitrotyrosine in bone marrow-derived EPCs.

EPCs were harvested from the bone marrow derived from the femur and tibia from ischemic and non-ischemic hindlimbs 7 days after induction of ischemia. m ± sd; n = 3 animals in each group; # P<.05 type 1 or type 2 diabetic mice vs. control mice, * P<.05 type 2 diabetic mice vs. type 1 diabetic mice, + P<.05 ischemic hindlimb vs. non-ischemic hindlimb. Insets present representative western blots; lane designations from left to right: control, non-ischemic hindlimb; control, ischemic hindlimb; type 1 diabetes, ischemic hindlimb; type 1 diabetes, non-ischemic hindlimb; type 2 diabetes, non-ischemic hindlimb; type 2 diabetes, ischemic hindlimb. (A) eNOS expression. (B) Nitrotyrosine expression.

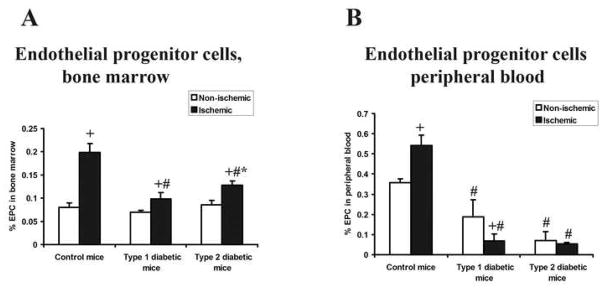

Effect of ischemia on the concentration of EPC in bone marrow and peripheral blood

The number of EPC (CD34+, Flk-1+, CD133+) in the bone marrow from the femur and tibia of the non-ischemic hindlimb was similar among all three study groups. All three study groups also demonstrated a greater number of bone marrow EPC in the femur and tibia of the ischemic than non-ischemic hindlimb; however, the magnitude of this difference was significantly greater in control mice than in either diabetic group. Moreover, the percentage of EPC in bone marrow from the ischemic hindlimb was greater in type 2 than type 1 diabetic mice (figure 7A). EPC concentration in peripheral blood was greater in control mice than in either diabetic group and this value was significantly less in type 2 than type 1 diabetic mice. The concentration of EPC in peripheral blood increased after induction of ischemia in control mice. In contrast, this level decreased in type 1 diabetic mice and remained unchanged in type 2 diabetic mice. Consequently, the peripheral blood EPC concentration following induction of ischemia was significantly lower in both diabetic groups than in control mice (figure 7B).

Figure 7. Percentage of EPCs in bone marrow and peripheral blood samples.

Peripheral blood and bone marrow (harvested from the femur and tibia of the non-ischemic or ischemic hindlimbs) was obtained 7 days after induction of ischemia. EPCs were characterized as CD34+, Flk-1+, CD133+ and cell quantitation was carried out by FACS analysis. m ± sd; n = 6 animals in each group; # P<.05 type 1 or type 2 diabetic mice vs. control mice; * P<.05 type 2 diabetic mice vs. type 1 diabetic mice, + P<.05 ischemic hindlimb vs. non-ischemic hindlimb.

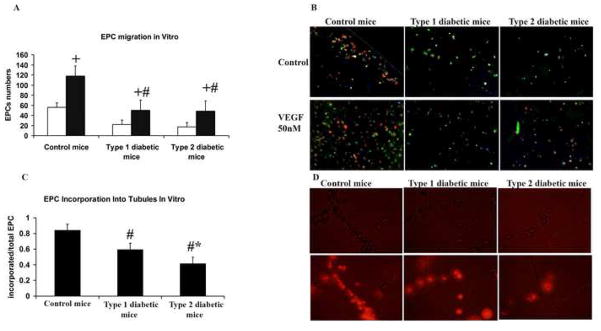

Effect of ischemia on EPC function

VEGF-induced EPC migration was significantly greater in control mice than in type 1 or type 2 diabetic mice (figure 8A). EPCs from both type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice showed significantly impaired EPC incorporation into tubular structures than control mice. However, the magnitude of this impairment was greater in EPC from type 2 than type 1 diabetic mice (Figure 8C).

Figure 8. EPC in vitro functional assays.

EPCs were harvested from the femur and tibia of ischemic and non-ischemic hindlimbs 7 days after the induction of ischemia and grown in culture for 3 days. (A) EPC migration assay. Open bars represent migration in response to medium alone (baseline), while filled bars represent migration in response to VEGF. m ± sd; n = 6 animals in each group; + P<.05 migration in response to VEGF vs. migration in response to medium; # P<.05 type 1 or type 2 diabetic mice vs. control mice. (B) Representative photomicrograph of migration assay. UE lectin is stained green, Dil-Ac-LDL is stained red, and nuclei are stained blue. All photomicrographs were taken at a magnification of 200×. (C) Incorporation of EPCs into tubular structures. m ± sd; n = 6 animals in each group; # P<.05 for type 1 or type 2 diabetic mice vs. control mice. (D) Representative photomicrograph of tubular incorporation studies. The upper panels are bright field images. The lower panel are fluorescent images. EPCs are stained red. All photomicrographs were taken at a magnification of 200×.

Discussion

The present report offers the first evidence that type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice demonstrate different vascular responses to severe hindlimb ischemia under identical experimental conditions. This difference was best evidenced by less effective hindlimb blood recovery in type 2 than in type 1 diabetic mice; as well, marked adipocyte infiltration was evident in the ischemic hindlimb muscle of type 2, but not type 1 mice. We propose that differences in eNOS expression and oxidant stress, both within ischemic muscle and in EPC, as well as differences in EPC function between type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice explain, in part, the disparate vascular responses between groups.

Arteriogenesis is defined as the anatomic enlargement of collateral artery diameter in response to occlusion or obstruction of a major conduit artery.21 The physiological effect of this remodeling is increased collateral vascular conductance, resulting in restoration of downstream blood flow.21 This definition was fully satisfied in the ischemic limb of control mice indicating the presence of arteriogenesis in this group; thus, collateral diameter was 58% greater in the ischemic versus the non-ischemic hindlimb, while foot perfusion was restored to 65% of baseline. The response was less clear in the diabetic groups. Collateral artery diameter was smaller in type 2 than in type 1 diabetic mice in both the ischemic and the non-ischemic hindlimb. The latter finding might indicate that the effect of type 2 diabetes on collateral artery dimension is longstanding, i.e., that it might reflect an effect on collateral artery development, possibly a deficiency in the responsiveness to shear stress, a critical stimulus for collateral development.21 Anatomic evidence of arteriogenesis in response to ischemia was not present in type 1 or type 2 diabetic mice as neither group demonstrated a difference in collateral diameter between the ischemic and non-ischemic hindlimbs, a finding consistent with the studies of Schiekofer et al.22 in db/db mice and Tamarat et al.5 in streptozoticin-treated mice. However, we found that post-ischemic recovery of hindlimb perfusion was clearly greater in type 1 than in type 2 diabetic mice, i.e., there was a disparity between anatomic (collateral diameter) and physiologic (hindlimb perfusion) data. Reconciliation of this inequality cannot be achieved based on existent findings. We speculate that a more concentrated study of collaterals, categorizing vessel dimension as a function of anatomic location between specific muscles or increasing the number of collaterals measured in each mouse, might generate anatomic evidence of arteriogenesis in type 1 diabetic mice.

Angiogenesis is defined as the de novo generation of capillaries in tissue downstream from the site of conduit vessel occlusion or obstruction.21 The capillary/myofiber ratio was less in the ischemic than in the non-ischemic gastrocnemius muscle from control mice and type 1 diabetic mice, indicating that post-ischemic angiogenesis did not occur in either group. Type 2 diabetic mice exhibited a ratio lower than type 1 or control mice in both ischemic and non-ischemic gastrocnemius muscles, signifying a reducing capillary density in these mice. Interestingly, in contrast to type 1 diabetic or control mice, the capillary/myofiber ratio in type 2 mice was similar between the ischemic and non-ischemic hindlimbs. One interpretation of this finding is that the existent capillary density was protected in type 2 mice, an effect that might reflect the reduced post-ischemic perfusion recovery in type 2 mice. Tissue O2 delivery is directly proportional to flow rate and one compensation for reduced O2 delivery is increased capillary density, which yields an increased rate of diffusion of available capillary O2 to cells.23 Moreover, reduced tissue O2 delivery increases tissue hypoxia, the primary stimulus for angiogenesis.24 Type 2 diabetic mice experienced the post-ischemic lowest flow rate and we speculate that this circumstance may have provided a greater stimulus for angiogenesis, thus precluding the reduction in the capillary/myofiber ratio noted in the ischemic gastrocnemius in type 1 diabetic and control mice. It remains, however, that type 2 diabetic mice did not demonstrate an increased capillary/myofiber ratio in the ischemic versus non-ischemic muscle and, in the strictest sense, we cannot conclude that post-ischemic angiogenesis occurred in this group

EPCs are bone marrow-derived progenitor cells that are mobilized into the peripheral blood circulation in response to vascular injury and are essential participants in both arteriogenesis and angiogenesis within ischemic tissue.7–9 Prior to induction of hindlimb ischemia, the percentage of EPCs in peripheral blood was lower in both type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice than in the control group, despite the presence of similar levels of these cells in bone marrow prior to induction of ischemia in all three groups. This finding is consistent with observations previously made in patients with type 1 diabetes, where the percentage of circulating EPCs was noted to be depressed and the severity of diabetic vasculopathy was inversely correlated with the presence of EPCs in peripheral blood.25 The percentage of EPCs in peripheral blood in control mice increased 39% after induction of ischemia, whereas this percentage decreased in type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice at this time, indicating a failure of bone marrow mobilization of EPCs in response to hindlimb ischemia in both types of diabetic mice. Fadini et al.11 and Gallagher et al.10 reported similar finding in streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes in rat and mice, respectively. The present report, however, provides the first evidence of impaired EPC mobilization in type 2 diabetic mice.

Impairment of EPC in vitro function has been reported in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.12,13 The present findings indicate impaired VEGF-induced migration in marrow-derived EPCs from type 1 and 2 diabetic mice, as well as impaired incorporation of EPCs into tubular structures that was less effective in type 2 than type 1 diabetic mice. EPC participate in both arteriogenesis and angiogenesis.7 Impairment of EPC mobilization and function was evident in both type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice and these effects may explain, in part, the lack of a post-ischemic increase in collateral artery diameter (arteriogenesis) and capillary/myofiber ratio (angiogenesis) in these study groups. Huang et al.26 reported compromised arteriogenesis and angiogenesis in KKAy mice, a genetic model of type 2 diabetes. This group also noted significant improvement in the post-ischemic vascular response, in association with normalization of VEGF levels, and increased activation of eNOS and Akt following treatment with the PPARγ agonist pioglitazone. In this context, it is possible that the reduced EPC eNOS expression noted in both type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice may have contributed to the deficiency in arteriogenesis and angiogenesis in these mice and that treatment with a thiazolidinedinone, such as pioglitazone, might restore these post-ischemic responses.

An original and important observation made in this study was that extensive fat infiltration occurred in the ischemic calf muscles of type 2 diabetic mice. db/db mice are obese 18 and it might thus be argued that the observed fat infiltration was a reflection of this obesity; however, this fat infiltration only occurred in the ischemic hindlimb. We speculate that this change may reflect adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC). MSC are a bone marrow-derived progenitor cells that, like EPC, home to the site of vascular injury where they participate in arteriogenesis and angiogenesis.27,28 MSC are pluripotent cells that can differentiate into several cell types including chondrocytes, adipocytes, and endothelial cells.29 We propose that MSC which homed to the ischemic hindlimb in type 2 mice were stimulated to an adipocytic lineage, a fate that would effectively nullify their involvement in vascular repair or adaptation.

Multiple mouse models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes have been described. We selected the streptozotocin-induced hypoinsulinemic mouse as a model of type 1 diabetes because it reproducibly duplicates the rapid development of β-cell insulinitis and subsequent hypoinsulinemia characteristic of human type 1 diabetes.18 An alternative model is the non-obese diabetic mouse, a genetic model of type 1 diabetes.31 The NOD mouse, however, does not manifest full expression of the diabetic phenotype until 4 – 5 months of age and this expression is not robust in male mice. These conditions were deemed unacceptable as we wished to generate hindlimb ischemia at 2–3 months of age in male mice to facilitate comparison of our data with published reports. We selected the Leprdb/db mouse as a model for type 2 diabetes because it5 recapitulates the insulin resistance, moderate hyperglycemia, and atherogenic dyslipidemia characteristic human type 2 diabetes. A potential disadvantage of the db/db mouse is that leptin may directly affect the proinflammatory immune responses32 and affect T cell function,33 phenomena that may be relevant in angiogenesis.34 We recognize that animal models that faithfully duplicate human type 1 and type 2 diabetes do not exist. We contend, however, that this caveat does not nullify the importance of the present findings, particularly in light of the frequency with which these diabetic mouse models have been used by others.

An important methodological caveat is the means used to generate hindlimb ischemia. We utilized extirpation of the femoral artery, a commonly used experimental model but one which generates acute severe limb ischemia and inflammation.4 This circumstance does not recapitulate the progressive narrowing of the iliac, femoral, or popliteal arteries that characterizes peripheral arterial disease, and comparison between acute versus chronic occlusion of the femoral artery in rats indicates that muscle hypoxia and necrosis were greater, and angiogenesis less effective following acute occlusion.20 Unfortunately, the ameroid constrictor used to generate chronic hindlimb ischemia in that study is too large for use in mice. It is possible that the lack of post-ischemic collateral artery enlargement (arteriogenesis) noted in diabetic mice may reflect the abrupt generation of ischemia used herein, insofar as collateral development appears to occur in diabetics with peripheral arterial disease. A second caveat to the study design was the use of the contralateral, non-ischemic hindlimb as an internal control for each mouse. It is possible that incision of a hindlimb and subsequent femoral artery extirpation therein generates a systemic response that affects the contralateral, non-operated hindlimb. Indeed, this effect might explain the finding that muscle eNOS expression in the contralateral, non-ischemic hindlimb in type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice was less than that of the control group.

We conclude that the vascular response to hindlimb ischemia in diabetic mice is contingent upon the type of diabetes present. Type 2 diabetic mice demonstrated significantly less restoration of hindlimb perfusion 28 days after induction of hindlimb ischemia. Both type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice failed to mobilize bone marrow-derived EPCs to the peripheral circulation in response to hindlimb ischemia, whereas type 2 diabetic mice displayed greater reduction of EPC function in vitro (incorporation into tubules) than type 1 diabetic mice.

Acknowledgments

Supported by HL75353 (to LMM). The authors acknowledge the assistance of Robert Raffai in the development of the type 1 diabetes model in our laboratory.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications. A unifying hypothesis. Diabetes. 2005;54:1615–1624. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazzone T, Chait A, Plutzky J. Cardiovascular disease risk in type 2 diabetes mellitus: insights from mechanistic studies. Lancet. 2008;371:1800–1809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60768-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Weel V, de Vries M, Voshol P, Verloop R, Eilers P, van Hinsbergh V, van Bockel H, Quax P. Hypercholesterolemia reduces collateral artery growth more dominantly than hypergylcemia or insulin resistance in mice. Arterioscler Thrombv Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1383–1390. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000219234.78165.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waters R, Terjung R, Peters K, Annex B. Preclinical models of human peripheral arterial occlusive disease: implications for investigating therapeutic agents. Am J Physiol. 2004;97:773–780. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00107.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamarat R, Silvestre JS, Ricousse-Roussanne SL, Barateau V, Lecomte-Raclet L, Clergue M, Duriez M, Tobelem G, Levy BI. Impairment in ischemia-induced neovascularization in diabetes. Bone marrow mononuclear cell dysfunction and therapeutic potential of placenta growth factor treatment. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:457–466. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63136-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emanueli C, Caporali A, Krankel N, Cristofaro B, Van Linthout S, Madeddu P. Type-2 diabetic Lepr (db/db) mice show defective microvascular phenotype under basal conditions and an impaired response to angiogenesis gene therapy in the setting of limb ischemia. Front Biosci. 2007;12:2003–2012. doi: 10.2741/2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urbich C, Dimmeler S. Endothelial progenitor cells. Characterization and role in vascular biology. Circ Res. 2004;95:343–354. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000137877.89448.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, Silver M, van der Zee R, Li T, Witzenbicher B, Schatterman G, Isner JM. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi T, Kalka C, Masuda H, Chen DH, Silver M, Kearney M, Magner M, Isner JM, Asahara T. Ischemia- and cytokine-induced mobilization of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells for neovascularization. Nature Medicine. 199(5):434–438. doi: 10.1038/7434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallagher KA, Liu ZJ, Xiao M, Chen HY, Goldstein LJ, Buerk DG, Nedeau A, Thom SR, Velazquez OC. Diabetic impairments in NO-mediated endothelial progenitor cell mobilization and homing are reversed by hyperoxia and SDF-1α. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1249–1259. doi: 10.1172/JCI29710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fadini GP, Sartore S, Schiavon M, Albiero M, Baesso I, Cabrelle A, Agostini C, Avogaro A. Diabetes impairs progenitor cell mobilization after hindlimb ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Diabetologia. 2006;49:3075–3084. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tepper OM, Galiano RD, Capla JM, Kalka C, Gagne PJ, Jacobowitz GR, Levine JP, Gurtner GC. Human endothelial progenitor cells from Type II diabetic patients exhibit impaired proliferation, adhesion, and incorporation into vascular structures. Circulation. 2002;106:2781–2786. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039526.42991.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loomans CJ, de Koning EJP, Staal FJT, Rookmaaker MB, Verseyden C, de Boer HC, Verhaar MC, Braam B, Rabelink TJ, van Zonneveld AJ. Endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction—A novel concept in the pathogenesis of vascular complications of Type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53:195–199. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aicher A, Heeschen C, Mildner-Rihm C, Urbich C, Ihling C, Technau-Ihling K, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Essential role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase for mobilization of stem and progenitor cells. Nature Medicine. 2003;9:1370–1376. doi: 10.1038/nm948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lloyd P, Yang H, Terjung R. Arteriogenesis and angiogenesis in rat ischemic hindlimb: role of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:H2528–H2538. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.6.H2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorrentino SA, Bahlmann FH, Besler C, Muller M, Schulz S, Kirchhoff N, Doerries C, Horvath T, Limbourg A, Limbourg F, Fliser D, Haller H, Drexler H, Landmesser U. Oxidative stress impairs in vivo reendothelialization capacity of endothelial progenitor cells from patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus-restoration by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor- agonist rosiglitazone. Circulation. 2007;116:163–173. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.684381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thum T, Fraccarollo D, Schultheiss M, Froese S, Galuppo P, Widder J, Tsikas D, Ertl G, Bauersachs J. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling impairs endothelial progenitor cell mobilization and function in diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:666–674. doi: 10.2337/db06-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rees D, Alcolado J. Animal models of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Med. 2005;22:359–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hummel K, Dickie M, Coleman D. Diabetes, a new mutation in the mouse. Science. 1966;153:1127–1128. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3740.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang GL, Chang DS, Sarkar R, Wang R, Messina LM. The effect of gradual or acute arterial occlusion on skeletal muscle blood flow, arteriogenesis, and inflammation in rat hindlimb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaper W, Scholz D. Factors regulating arteriogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1143–1151. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000069625.11230.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiekofer S, Glasso G, Sato K, Kraus BJ, Walsh K. Impaired revascularization in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes is associated with dysregulation of a complex angiogenic-regulatory network. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1603–1609. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000171994.89106.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Granger H, Goodman A, Granger D. Role of resistance and exchange vessels in local microvascular control of skeletal muscle oxygenation in dog. Circ Res. 1976;38:379–385. doi: 10.1161/01.res.38.5.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito W, Arras M, Scholz D, Winkler B, Htun P, Schaper W. Angiogenesis but not collateral growth is associated with ischemia after femoral artery occlusion. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H1255–H1265. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.3.H1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fadini G, Sartore S, Albiero M, Baesso I, Murphy E, Menegolo M, Grego F, Kreutzenberg S, Tiengo A, Agostini C, Avogaro A. Number and function of endothelial progenitor cells as a marker of severity for diabetic vasculopathy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2140–2146. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000237750.44469.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang P-H, Sata M, Nishimatsu H, Sumi M, Hirata Y, Nagai R. Pioglitazone ameliorates endothelial dysfunction and restores ischemia-induced angiogenesis in diabetic mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2008;62:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schatteman GC, Hanlon HD, Jiao CH, Dodds SG, Christy BA. Blood-derived angioblasts accelerate blood-flow restoration in diabetic mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:571–578. doi: 10.1172/JCI9087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinnaird T, Stabile E, Burnett M, Shou M, Lee W, Barr S, Fuchs S, Epstein S. Local delivery of marrow-derived stromal cells augments collateral perfusion through paracrine mechanisms. Circulation. 2004;109:1543–1549. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124062.31102.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pittenger M, Mackay A, Beck S, Jaiswal R, Douglas R, Mosca J, Moorman M, Simonetti D, Craig S, Marshak D. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–146. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kikutani H, Makino S. The murine autoimmune diabetes model: NOD and related strains. Adv Immunol. 1992;51:285–322. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60490-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leiter E. The genetics of diabetic susceptibility in mice. FASEB J. 1989;3:2231–2241. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.11.2673897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loffreda S, Yang S, Lin H, Karp C, Brengman M, Wang D, Klein A, Bulkley G, Bao C, Noble P, Lane M, Diehl A. Leptin regulates proinflammatory immune responses. FASEB J. 1998;12:57–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin-Romero C, Santos-Alvarez J, Goberna R, Sánchez-Margalet V. Human leptin enhances activation and proliferation of human circulating T lymphocytes. Cell Immunol. 2000;199:15–24. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stabile E, Kinnaird T, la Sala A, Hanson S, Watkins C, Campia U, Shou M, Zbinden S, Fuchs S, Kornfeld H, Epstein S, Burnett M. CD8+ T lymphocytes regulate the arteriogenic response to ischemia by infiltrating the site of collateral development and recruiting CD4+ mononuclear cells through expression of IL-16. Circulation. 2006;113:118–124. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.576702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]