Abstract

Pain and substance abuse co-occur frequently, and each can make the other more difficult to treat. A knowledge of pain and its interrelationships with addiction enhances the addiction specialist’s efficacy with many patients, both in the substance abuse setting and in collaboration with pain specialists. This article discusses the neurobiology and clinical presentation of pain and its synergies with substance use disorders, presents methodical approaches to the evaluation and treatment of pain that co-occurs with substance use disorders, and provides practical guidelines for the use of opioids to treat pain in individuals with histories of addiction. The authors consider that every pain complaint deserves careful investigation and every patient in pain has a right to effective treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Pain is integral to life; it is a critical component of the body’s natural defense system, signaling threats to body integrity and provoking self-preservation behaviors to further survival. Because pain often signals an urgent need to act (e.g., to flee, strike back, or otherwise respond aggressively to a threat), significant pain is typically associated with strong feelings (e.g., combinations of fear, anxiety, anger, or rage). Pain also sometimes occurs in the absence of any discernible threat or identifiable tissue damage, due to alterations in normal neural processing. It is not uncommon, therefore, to encounter distressed patients complaining of pain for which the origin is elusive.

When pain is complicated by a co-occurring addictive disorder, particularly in a patient using opioids for pain control, evaluation and treatment may present a complex clinical challenge to care providers and generate considerable frustration and prolonged suffering for the patient. In this as in other contexts, all complaints of pain must be taken seriously and carefully evaluated, because pain alone can impair health, function, and quality of life. Addiction professionals can contribute valuable perspective and skills to the care of these patients, and more so if they possess a working understanding of pain’s mechanisms, evaluation and management, and interrelationships with substance use.

The Prevalence of Pain

Virtually everyone experiences moderate to severe acute pain at some time, most often in association with surgical procedures, medical conditions, or physical trauma. Untreated acute pain causes unnecessary suffering, prolongs hospital stays, increases medical costs, and may progress to chronic pain (Young Casey et al., 2008). Epidemiological studies indicate that more than 50 million Americans are experiencing chronic pain at any given time. Chronic pain decreases quality of life and work productivity, and the societal costs of untreated chronic pain are high (Collins et al., 2005; McCarberg and Billington, 2006). The economic burden of untreated pain in the United States is estimated to be more than $100 billion per year (see men.webmd.com/features/price-tag-on-pain).

The Nexus of Substance Use Problems and Pain

The lifetime prevalence of alcohol abuse disorders in the U.S. general population is estimated at 16 to 24 percent (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 1998), and about 8 percent of Americans aged 12 and older report use of an illicit substance within the past month (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2007). Substance use disorders are significantly more common in many medical populations and, for example, reach 19 to 26 percent among hospitalized patients (e.g., Brems et al., 2002), 40 to 60 percent among persons sustaining major trauma (Heinemann et al., 1988; Norman et al., 2007), and 5 to 67 percent among persons being treated for depression (Sullivan et al., 2005). Because the same populations are at high risk for experiencing acute and chronic pain, the prevalence of substance use problems among persons treated for pain is high.

Conversely, pain is common in populations seeking treatment for addictive disease. A recent study found that 37 percent of patients in methadone maintenance treatment programs (MMTPs) and 24 percent of patients admitted for treatment of addiction experienced severe chronic pain (Rosenblum et al., 2003). In this study, 80 percent of MMTP patients and 78 percent of inpatients reported pain of some type and duration.

Clinical and Ethical Challenges

Persons with substance use disorders are less likely than others to receive effective pain treatment (Rupp and Delaney, 2004). The primary reason is clinicians’ concern that they may misuse opioids. Although mild to moderate pain can often be treated effectively with a combination of physical modalities (e.g., ice, rest, and splints) and nonopioid analgesics (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], acetaminophen, or other adjuvant medications), management of severe pain, especially when cancer-related, often requires opioids. Moreover, physicians are increasingly using opioids to treat chronic non-cancer-related pain, and an emerging body of evidence suggests that, for some patients, this approach both reduces pain and may foster modest improvements in function and quality of life (Devulder, Richarz, and Nataraja, 2005; Haythornthwaite et al., 1998; Kalso et al., 2004; Martell et al., 2007; Noble et al., 2008; Passik et al., 2005; Portenoy et al., 2007; Portenoy and Foley, 1986).

The use of opioids in persons with a history of substance use disorders raises not only complex clinical issues, but also ethical issues. The principles of beneficence and justice demand that all persons have equal access to effective pain treatment; however, the obligation to provide relief can come into tension with the principle of nonmaleficence (primum non nocere, “first, do no harm”) when a patient’s substance use problem raises concerns about potential medication misuse and resulting harmful consequences (Cohen et al., 2002).

THE EXPERIENCE OF PAIN

Chronic pain complicates the efforts of many individuals with substance use disorders to enter and sustain recovery (Passik et al., 2006a). An understanding of the nature and components of pain can help addiction professionals to understand the relation of each client’s pain to his or her addiction and thereby to provide more effective assistance on the path to recovery.

The Multidimensional Nature of Pain

In the early 1970s, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) adopted a definition of pain that is still widely accepted. It states that pain is “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience, associated with actual or threatened tissue damage, or described in terms of such” (IASP Task Force on Taxonomy, 1994, p. 213). This definition honors the understanding that pain is subjective, an experience rather than an objectively verifiable occurrence; it recognizes that pain has both sensory and affective dimensions; and it affirms that pain can exist in the absence of actual tissue pathology. In affirming the subjective, emotional, and sensory nature of pain and the fact that it may occur in the absence of an identifiable cause, the definition encourages clinicians to address all complaints of pain seriously.

Although some persons may feign pain in order to obtain opioids for non-pain-related purposes, and persons with co-occurring pain and addiction sometimes may have difficulty knowing where pain ends and a craving for opioids begins, most pain complaints are driven by real distress, the components of which usually can be defined with careful evaluation. Dynamic radiological studies such as positron emission tomography (PET) scans and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) yield useful objective anatomical and physiological information about pain in experimental contexts and hold promise for future clinical use in pain documentation (Mackey and Maeda, 2004). However, given the complex nature of the experience of pain, such technology is unlikely to be a reliable clinical tool to distinguish actual from feigned or mislabeled pain in the near future, if ever.

The spectrum of chronic pain disorders experienced by persons with addictive disorders is similar to that of the general population. Common syndromes include headache, low-back and neck pain, myalgias and arthralgias, dental pain, neuropathies, and abdominal/pelvic pain. Regardless of its anatomical focus, all pain draws from a shared pool of etiological mechanisms and shares general principles of evaluation and management.

The Classification of Pain

Pain can be classified in terms of its physiological mechanisms and its duration. Physiologically, an individual’s pain derives from a nociceptive, neuropathic, or mixed mechanism. Temporally, the pain is acute if it resolves along with its initiating physical causes, and chronic if it persists.

Physiological Basis of Pain

Nociceptive Pain

Nociceptive pain is induced by actual tissue damage. It is evoked by intense stimulation of sensory receptors that alert the body to a potential for physical harm. Usually, the pain occurs at the site of the insult (Figure 1). The sensation most often reflects the type of stimulus (e.g., spasms feel tight; cuts feel sharp; and burns feel hot). Nociceptive pain is often self-limited, resolving spontaneously as the threat passes or the injury heals. It may persist, however, if tissue damage persists (for example, in chronic degenerative arthritis or advancing cancer). Nociceptive pain may be intermittent when the cause is intermittent, for example, in acute recurrent pancreatitis or sickle cell anemia. The cause of nociceptive pain usually becomes apparent from the patient’s history, a physical examination, and/or imaging or laboratory studies.

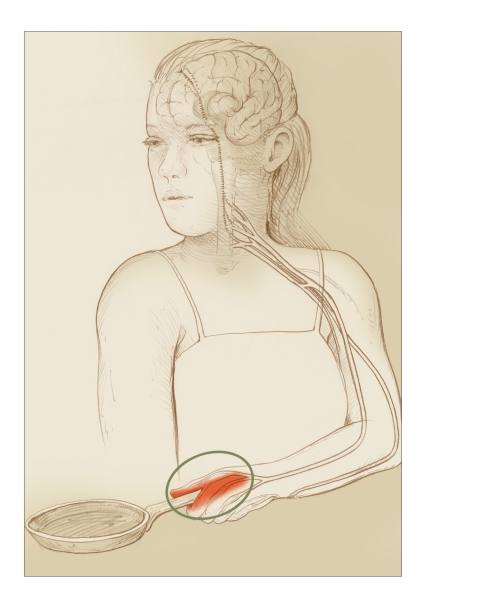

FIGURE 1.

Nociceptive Pain

In nociceptive pain, sensory nerves function normally. The place where pain signals originate and the place that hurts are the same—in this case, a hand that has come into contact with a hot object.

Neuropathic Pain

Neuropathic pain results from aberrant functioning along the neural pathways that normally conduct nociceptive pain (Figure 2). There are numerous types of neuropathic pain. Among the more common:

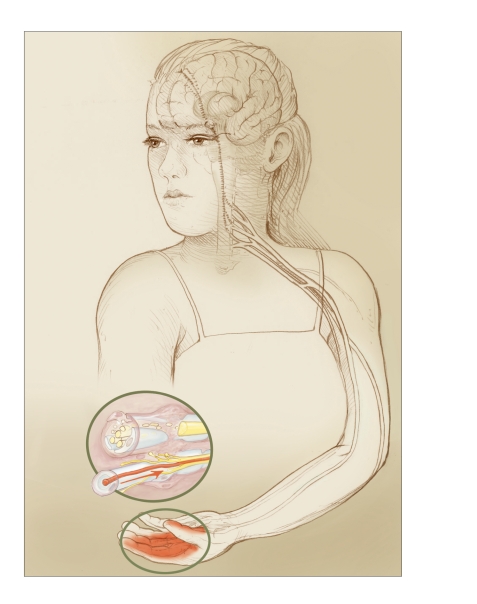

FIGURE 2.

Neuropathic Pain

In neuropathic pain, injury to nerves (inset) or changes in processing of nerve signals may spontaneously generate pain signals, though no fresh injury or insult is occurring. Here, changes in nerve processing at different points along the pain pathways may cause the woman’s hand to hurt even after her tissues have otherwise healed.

Tissue may compress a nerve, as in a lumbar disc rupture or carpal tunnel syndrome, which causes pain in the area served by the nerve.

Peripheral nerve fibers that have been injured by laceration or prolonged compression may regenerate in a disorganized manner, producing either neuritis (resulting in abnormal signal conduction) or a neuroma (clumped aggregation of neural fibers) that perpetuates pain with minimal or no stimulus. (For another example, see Figure 3.)

Impaired blood supply associated with peripheral vascular disease or hyperglycemia associated with diabetes may impair small nerve fiber function in the hands or feet, causing bilateral symmetrical pain (peripheral neuropathy).

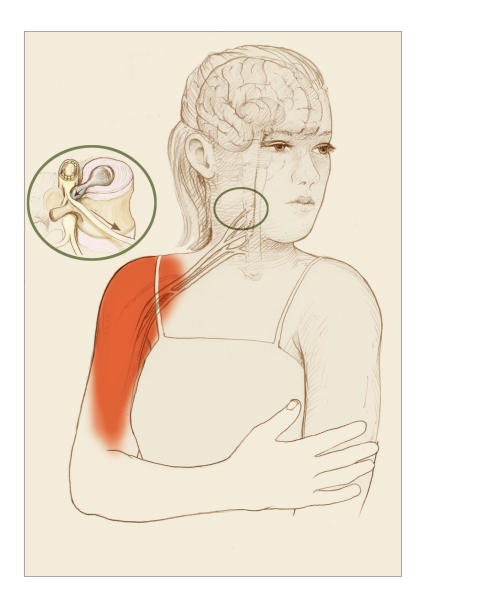

FIGURE 3.

Displaced Sensation of Neuropathic Pain

In some types of neuropathic pain, the source of the pain and the sensation of hurt occur in different locations. In this example, one of the spongy discs that alternate with the spinal vertebrae has ruptured, leaking material that presses on an adjacent large nerve fiber (inset). Pain signals travel from the pinched fiber to the brain, which interprets them as coming from the peripheral tissues served by the fiber.

Neuropathic pain also can result from disruption of the normal relationship between peripheral neurons and the secondary neurons in the spinal cord that relay sensory signals to the brain and other sites. Thus, untreated severe nociceptive pain may cause a continuing barrage of stimuli to secondary neurons, resulting in hyper-reactivity or central sensitization of the nerves, which may then translate nonpainful signals into pain, sometimes termed “wind-up phenomena” (Curatolo et al., 2006). Conversely, loss of neural input into the spinal cord—for example, following loss of a limb—may result in amplification of signals coming from the periphery and lead to deafferentation or “phantom” pain.

Still other types of neuropathic pain have central or regional origins. Injury to certain parts of the central nervous system—such as the thalamus, a prominent pain-processing center in the brain, due to a stroke (Jensen and Lenz, 1995) or the dorsal horn, a pain-processing center of the spinal cord, due to herpes zoster or shingles—may cause pain in body areas whose neural signals travel through the injured area (Figure 4). Aberrant central neural processing of nonpain signals due to abnormal neurotransmitter activity is now thought likely to be responsible for fibromyalgia syndrome, which presents with diffuse, generalized, or multifocal pain (Mease, 2005). Persistent arousal of a localized region of the sympathetic nervous system may contribute to a complex regional pain syndrome, a neuropathic pain of complex etiology (Burton, Bruehl, and Harden, 2005).

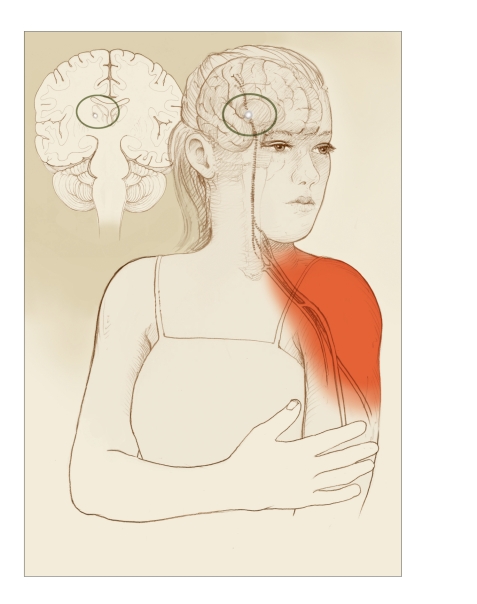

FIGURE 4.

Neuropathic Pain With Damaged Pain-Processing Areas of the Brain

Damage to pain-processing areas in the brain also can result in neuropathic pain that is “referred”—that is, felt elsewhere. In this example, an injury to the thalamus (inset) causes pain in a shoulder.

Neuropathic pain has variable presentations, but most often is described as burning, shooting, aching, tingling, electrical, or “pins and needles,” often with an associated sense of numbness. Objective physical findings in neuropathic pain are sometimes subtle or nonexistent, making the patient’s history and pain description especially important to the diagnosis. This may lead to skepticism on the part of care providers that becomes the basis for a mistrustful therapeutic relationship, particularly when the patient has a history of substance use and opioids may be indicated for treatment.

Mixed Pain Mechanisms

Many common pain syndromes combine nociceptive and neuropathic pain. Back pain due to severe degenerative arthritis may be associated with referred leg pain caused by degenerative changes that are compressing or injuring a lumbar nerve root. Neck pain following a cervical strain may be due to spinal facet joint irritation and to cervical muscle spasm, which in turn may cause brachial plexus irritation and referred arm pain. A person with a peripheral neuritis due to nerve injury in the leg may have an abnormal gait that leads to mechanical back pain. A cancer tumor may cause pain due to both local tissue invasion and neural compression. Headaches have many different etiologies, but some are due to cervical muscular tension with irritation of the greater occipital nerves that radiates pain to the back of the head and temples. Generalized neuropathic pain may be superimposed on a focal pain syndrome, for example, when a severely painful nondisplaced bone fracture is undetected, no pain treatment is provided, and secondary sensitization develops, presenting as a generalized pain syndrome in which “everything hurts.”

Acute and Chronic Pain

Acute pain has an abrupt onset and can be severe (see www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/paincontrol/page2). It is usually associated with an acute physical condition, and its etiology is usually—though not always—known or identifiable. The pain is self-limited and generally resolves as the underlying injury or disease process resolves. Acute pain is often primarily nociceptive, but may have a neuropathic component if nerves are affected by a lesion or process. Severe acute pain frequently is associated with sympathetic responses reflected in signs such as increased blood pressure and pulse, sweating, blanching of the skin, and hyperventilation. An individual in acute pain often appears distressed.

Chronic pain differs from acute pain in that it no longer serves survival or any other beneficial purpose and has lingered past the limits normally associated with tissue healing (Mersky and Bogduk, 2004). It may persist because of chronic ongoing tissue pathology (e.g., degenerative arthritis, persistent muscle spasm, chronic pancreatitis, or progressive cancer), an established neuropathic pain mechanism, or a combination of the two.

Pain that persists for a prolonged period of time often engenders secondary problems, such as sleep disturbance; anxiety; depressive symptoms; loss of normal function in work, social situations, and recreation; and increased stress associated with these losses. In turn, fatigue, mood disturbance, and stress may expand the experience of pain; such cycles often sustain the experience of chronic pain even when the physiological basis improves. Sometimes, the underlying physiological basis of chronic pain is difficult to determine with precision, because it is wrapped in many layers of associated problems and distress. Effective treatment of chronic pain often must address the context in which the pain occurs, the multidimensional impact of the pain, and the feedback cycles that may serve to sustain it.

Chronic pain is not usually associated with sympathetic arousal. Therefore, objective signs of physiological stress are often absent, and persons with chronic pain may not appear to be hurting. In such cases, observers are sometimes skeptical, particularly when substance problems or opioid medications are involved. However, persons with chronic pain also may experience periods of acute exacerbation that are associated with sympathetic responses and more obvious physical distress.

The Synergy of Pain and Addiction

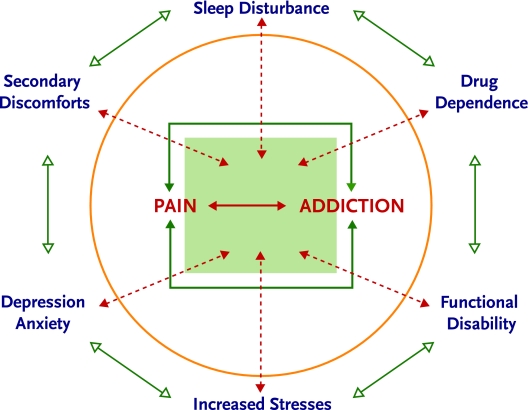

Addiction may affect the experience of pain in a number of ways. Although an addicted individual may perceive that alcohol or drug use helps him or her cope with ongoing pain, the reality is generally otherwise. When chronic pain and addiction co-occur, each may reinforce components of the other (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Synergy of Pain and Addiction

Like chronic pain, addiction often results in non-restorative sleep, anxiety and/or depression, inability to function in important life roles, and resultant stress. In addition, persons who are addicted to a substance rarely use it in a manner that creates a steady state and physiological homeostasis. Rather, they tend to experience periods of intoxication, followed by periods of withdrawal. The alternation of periods of relative autonomic and psychomotor inactivity during intoxication with periods of physiological stress, sympathetic arousal, and muscular tension during withdrawal has been characterized as “on–off” or rebound phenomenon, and may increase pain (Dunbar and Katz, 1996; Pud et al., 2006; Savage, 1993). Also, addicted individuals may have difficulty complying with pain treatment recommendations because of intoxication and time spent pursuing drugs. Clearly, treatment of an active addiction is critical to the effective management of chronic pain. The individual with both pain and addiction, however, may perceive his or her drug use as transiently reducing pain or improving coping; thus, it is important for addiction professionals to provide education on the synergy of pain and addiction.

In the acute pain setting, the pain treatment plan must accommodate physical dependence on alcohol, opioids, or other drugs, because initiating withdrawal may increase pain and interfere with compliance and efficacy. At the same time, acute pain associated with trauma, surgery, and illness may present an opportunity for intervention in substance abuse or addiction, because patients are confronted with possible withdrawal and their overall vulnerability related to substance use.

The Uniqueness of Each Pain Experience

Whatever the physiological basis of pain, the experience is filtered through the individual’s biopsychosocial context. The same pain generator may therefore be experienced very differently by different individuals, depending on their biogenetic makeup, sociocultural expectations, gender, co-occurring medical and psychiatric conditions, and other factors (Kim et al., 2004).

PRINCIPLES OF PAIN ASSESSMENT

Addiction professionals may need to evaluate pain and consider pain management approaches for their patients in a number of situations. Some patients in addiction treatment struggle to enter recovery because of persistent pain that interferes with substance cessation; some patients in recovery develop pain that threatens sobriety; and some patients have difficulty discerning whether prescribed opioids continue to be necessary for their underlying pain or whether their continued need is related to craving that is masquerading as pain. Although addiction clinicians will not employ all elements of pain assessment and treatment, they will be better able to support effective pain management if they possess a broad understanding of the relevant principles.

In acute settings, where pain is consistent with an identified or suspected cause and is likely to be self-limited, the only critical assessment is often pain intensity, which provides a basis for evaluating the effectiveness of interventions. Clinicians usually ask patients to rate their pain intensity with a numerical rating scale of 0 to 10 or a visual analog scale. Sometimes verbal descriptor scales and facial distress image scales may be useful, particularly in children or persons with cognitive challenges.

When pain is persistent, clinicians must assess not only the pain itself, but its overall impact on the individual, including associated psychosocial factors. The workup should include a detailed assessment of the pain, including its intensity, quality, location, and radiation; identification of factors that increase and decrease the pain; and a review of the effectiveness of any interventions that have been tried to relieve the pain. The intensity of chronic pain often fluctuates, and knowledge of the pattern may help guide treatment; therefore, it may be helpful to inquire not only about current pain, but also about the worst, least, and typical pain experienced over the past week. In addition, it is important to ask the patient what level of pain permits a good quality of life, as different individuals find widely varying levels of pain acceptable or debilitating.

The impact of chronic pain on sleep; mood; level of stress; and function in work, relationships, and recreational activities should be assessed, because improvement in these domains may be a goal of pain treatment and a measure of the efficacy of interventions. Numerous screening instruments are available to assist in these assessments, including, among many others, the Brief Pain Inventory; the Roland Morris Disability Scale; and the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire, which is a brief measure to identify depression, the most common psychiatric problem seen among pain patients. Assessment of co-occurring medical and psychiatric conditions is important in order to appreciate variables that may impede pain recovery. A physical examination and imaging and laboratory studies may be helpful diagnostically, but these are not generally included in a non-medical addiction professional’s assessment.

Assessment of medication and other drug use is critical to understanding and addressing pain, particularly in persons at risk for or with a history of substance use disorders. Useful information includes:

What substances, including alcohol, illicit drugs, or prescription drugs, is the individual currently using? At what dosages? How often?

What substances does the individual believe ease, or help him or her cope with, the pain?

How does each substance affect the pain?

Do the substances have effects other than analgesia that the individual identifies as beneficial, such as reward/euphoria, sedation, relief of anxiety or depression, or sleep induction?

What unwanted effects or side effects does each substance have?

Does the individual experience withdrawal symptoms if he or she does not use the substance?

How is each substance obtained (e.g., prescribed, over the counter, borrowed, or bought on the street)?

Is the individual using any nonprescribed medications or street drugs that he or she does not relate to pain management?

PRINCIPLES OF PAIN TREATMENT

The armamentarium of pain treatment tools is vast and varied. The most appropriate interventions will depend on a number of variables, including the location and nature of the patient’s pain and its psychosocial context, the availability of specific interventions, the patient’s preferences, the treatment provider’s clinical orientation, and the relative risks and benefits of particular interventions vis-à-vis the patient’s other co-occurring conditions, including previous or ongoing substance use. Whenever possible, it is important to identify and address the underlying pain generator; this is the key to reducing all acute pain and many cases of chronic pain as well, although “fixing” the problem is not always possible in chronic pain.

Tools for managing pain fall into four broad categories: physical interventions, psychobehavioral approaches, interventionist treatments (invasive procedures), and medications (Table 1). Often a combination of approaches is most effective. Combining interventions that act at different points along the pathways of pain—for example, in the peripheral tissues, the nerves, the spinal cord, or the brain—may yield complementary additive or synergistic effects.

TABLE 1.

Common Pain Treatments

| PHYSICAL | PSYCHOBEHAVIORAL | INTERVENTIONIST | MEDICATION CLASSES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal: heat and ice | Relaxation, biofeedback | Nerve blocks and ganglion injections | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen |

| Counterstimulation: transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), vibration | Stress reduction, psychotherapy for co-occurring psychological stress issues | Steroid joint injections | Anticonvulsants |

| Exercise: stretching, strengthening, conditioning | Cognitive restructuring | Trigger point injections | Antidepressants with noradrenergic effects (e.g., tricyclics, duloxetine, venlafaxine) |

| Manual therapies: massage, manipulation | Pacing, behavioral modification | Epidural steroids | Topicals: lidocaine, capsaicin, aromatics |

| Orthotics, braces, pillows, splints | Treatment of mood disturbance | Spinal cord stimulation | Opioids |

| Acupuncture | Sleep management | Spinal infusions | Miscellaneous |

In general, addiction clinicians do not bear primary responsibility for directing pain treatment, but a familiarity with pain management options will enable them to advocate for appropriate treatment and to help patients identify and apply self-management strategies for pain. A knowledgeable and supportive advocate may be a patient’s most important asset in receiving effective care. In many cases, unfortunately, the greatest challenges lie in identifying skilled clinicians willing to work with patients with co-occurring pain and addiction and in finding financial support for treatment.

Treating Acute Pain

Mild to moderate acute pain is often relieved by physical interventions—such as the application of ice, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), massage or stretching, and/or bracing—along with a mild analgesic such as an NSAID or acetaminophen. More severe pain often requires opioid therapy, which will be discussed in depth below. When appropriately skilled clinicians are available in a system that is comfortable supporting such treatments, nerve blocks or spinal infusions can sometimes control more severe acute pain. Examples of common acute pain procedures are rib blocks for rib fractures or thoracic incisions; epidural infusions for thoracic, abdominal, or lower body surgery or trauma; and brachial plexus infusions for upper extremity postsurgical or trauma-related pain.

Clinicians should generally not let concerns about addiction deter them from using opioids that are needed for severe acute pain. Carefully supervised short-term use of opioids in the context of time-limited treatment of such pain has not been documented to affect the long-term course of addictive disorders. Rather, inadequate pain control and treatment that frustrates, stresses, or confuses patients may lead to relapse (Wasan et al., 2006).

Managing Chronic Pain

Although opioid therapy is sometimes a component of chronic pain management, nonopioid interventions control many cases of mild to moderately severe chronic pain. A specific treatment can sometimes significantly reduce or resolve chronic pain, but successful treatment is frequently a multidimensional process that demands the patient’s active engagement. Addiction treatment clinicians, as they work to induce and support recovery, are in an excellent position to help patients implement components of the pain management process. Common components include:

Raising the patient’s awareness of factors that increase and relieve the pain, and accommodating behaviors to reduce pain (e.g., cognitive-behavioral approaches);

Improving physical fitness, including flexibility, strength, and conditioning, while respecting any limits imposed by the pain;

Reducing stress and the associated muscular/autonomic tension;

Selectively using specific therapeutic interventions such as injections, therapeutic exercise, and orthotics;

Making strategic use of self-administered care interventions, such as the application of ice or heat, TENS, stretching, relaxation, and splints; and

Using nonopioid analgesic medications, such as acetaminophen, NSAIDs, tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and topically applied agents, singly or in combinations that take advantage of complementary mechanisms of action.

The goals of chronic pain treatment most often include, along with reduction of pain, relief of associated symptoms such as anxiety, depression, or sleep disturbance and increased function in valued social, vocational/avocational, creative, and recreational roles. Helping the patient to identify alternative avenues to satisfaction in these domains is sometimes necessary when pain or disability prevents participation in prior roles.

OPIOID CONSIDERATIONS IN PAIN TREATMENT

Despite important advances in pain treatment, opioids remain the most potent class of analgesic medications available. They relieve most types of pain, are widely available, and are generally safe when used appropriately. Unlike some other analgesics, opioids do not cause organ toxicity when used appropriately; in contrast, NSAIDs and acetaminophen can cause serious gastric, hepatic, and renal toxicities, which are responsible for 15.3 deaths per 100,000 users per year (Lanas et al., 2005; Nourjah et al., 2006). However, opioids may be misused by individuals to obtain an opioid high or to self-medicate mood disturbances, and in vulnerable individuals, use of opioids may lead to addiction. When misused, opioids can cause death through respiratory suppression leading to cardiac arrest. There is growing evidence that in some individuals, long-term opioid use may alter pain processing in a way that actually increases pain (Angst and Clark, 2006; Baron and McDonald, 2006; Chang, Chen, and Mao, 2007). Finding a balance between the benefits and risks of opioid use is often challenging and requires a fundamental understanding of opioid actions and conditions related to their use.

Prevalence of Opioid Misuse

The therapeutic use of opioids has increased significantly in recent years. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, which monitors the distribution of opioids through legitimate channels from manufacturer to pharmacy, recorded more than a quadrupling in annual quantities of oxycodone products and methadone distributed for therapeutic use between 1997 and 2002. Distribution of most other opioids increased as well, though less markedly. In a similar timeframe, between 1996 and 2001, emergency room visits related to misuse of prescription opioids more than doubled (Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2002). In 2003, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that 4.9 percent of adults and 7.7 percent of children between the ages of 12 and 17 acknowledged nonmedical use of a prescription opioid in the past month (SAMHSA, 2005). The number of people admitted to federally funded treatment centers with a primary diagnosis of prescription opioid addiction more than tripled, from 0.9 to 3.5 percent, between 1992 and 2004 (SAMHSA, 2005).

Diversion of prescription opioids from legitimate therapeutic channels is clearly occurring, but it is uncertain which points in the distribution system are leaking the most. Diversion at the level of patient prescriptions likely contributes substantially to illicitly available medications, but it appears that truck and pharmacy robberies also contribute (Joranson and Gilson, 2005). Individuals with substance use disorders appear to be at greatest risk for misuse of prescription opioids, but other variables carry a risk as well, including youth, smoking, a family history of addiction, and comorbid psychiatric problems associated with impulsivity (Kahan et al., 2006; Webster and Webster, 2005).

Opioid Analgesic Considerations

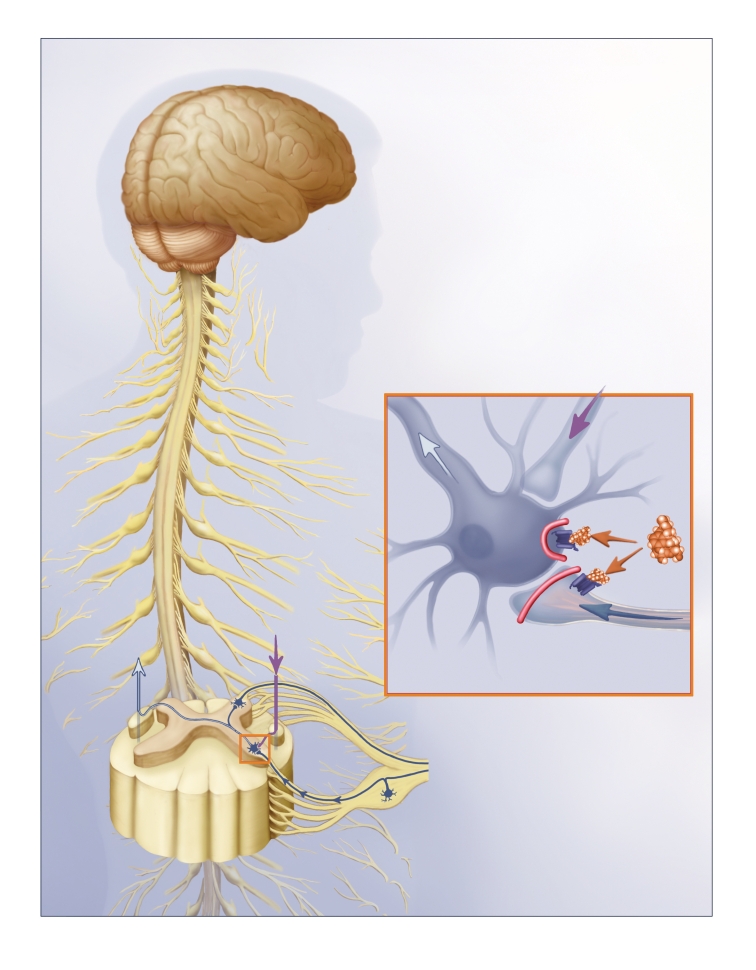

Opioids provide pain relief (analgesia) through action at mu, kappa, and/or delta receptors distributed throughout the central nervous system, including both the brain and spinal cord, and, to a lesser degree, the peripheral nervous system (Amabile and Bowman, 2006). Clinically available opioid medications act predominantly at mu or kappa receptors. Opioid receptor activation at different sites contributes to analgesia through several mechanisms, including direct inhibition of pain transmission at the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, activation of brain centers that transmit pain-inhibiting signals downward through pathways (serotonergic and noradrenergic) in the spinal cord, inhibition of pain receptors in the peripheral tissues, and stimulation of limbic activity that alters perceptual and affective responses to pain (Inturrisi, 2002).

Mu Opioids

The most commonly used opioid analgesics act at mu opioid receptors (Table 2; Figure 6). Most of these mu opioids can be titrated as needed to achieve relief of acute pain and have no ceiling of analgesia. Exceptions are tramadol (Ultram), which is dose-limited because it lowers the seizure threshold; meperidine (Demerol), whose metabolite, normeperidine, may be neurotoxic at high doses; codeine, which relies on metabolism to morphine for much of its analgesia but is not metabolized fast enough for unlimited pain control; and buprenorphine, which is a partial mu agonist that has an intrinsic ceiling effect. Recent evidence suggests that methadone at higher doses may contribute to cardiac arrhythmia in some patients; hence, titration to higher levels may require special cardiac monitoring (Peles et al., 2007). Opioids can relieve both somatic and neuropathic pain; however, there appears to be a shift in the dose–response curve in neuropathic pain syndromes, such that a higher dose of the opioid is required to achieve analgesia.

TABLE 2.

Mu Agonist Opioids and Kappa Opioids

| OPIOID | EXAMPLE BRANDS/PREPARATIONS | SPECIAL PAIN ISSUES | SPECIAL MISUSE ISSUES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mu Agonist Opioids | |||

| Morphine | MS Contin (12-hour CR), Kadian, Avinza (24-hour CR), Oramorph (IR) | CR mechanism provides relatively stable blood levels | CR mechanism may be altered for misuse |

| Oxycodone | Percocet (IR and acetaminophen), Percodan (IR and aspirin), OxyContin (12-hour CR) | CR mechanism provides relatively stable blood levels | CR mechanism may be altered for misuse |

| Hydrocodone | Vicodin (IR and acetaminophen), Lortab (IR and acetaminophen) | The most commonly prescribed opioid (Hughes, Bogdan, and Dart, 2007) | Most commonly misused opioid |

| Hydromorphone | Dilaudid (IR) | Quick onset; relatively high reward value | |

| Fentanyl | Duragesic (72-hour CR patch), Actiq (IR lozenge) | Patch provides very stable blood levels when used as prescribed | Misuse of patch can be particularly dangerous due to concentrated 3-day supply of opioid |

| Methadone | Methadose, Dolophine | Mu opioid; in addiction, promotes analgesia by a second mechanism: NMDA receptor antagonism; produces tolerance less readily than other mu opioids | Misuse and mortality related to misuse have recently increased; pharmacological properties make misuse particularly risky |

| Tramadol | Ultram (IR), Ultracet (IR with acetaminophen) | Promotes analgesia by a second mechanism: increasing serotonin/norepinephrine; doses are limited due to risk of seizures | Relatively low rates of abuse and reward documented in some persons |

| Buprenorphine | Subutex (used for pain, but not FDA approved for pain) | Partial agonist; ceiling effect; used off label for pain | Approved for treatment of opioid addiction; some IV abuse reported |

| Codeine | Tylenol #3 (IR with acetaminophen) | Metabolism to morphine is a rate-limiting step that creates a ceiling of analgesia in most people | |

| Kappa Opioids | |||

| Butorphanol | Stadol (IV or intranasal) | Rapid onset of intranasal; ceiling analgesic effects | Some patients experience less reward than with mu opioids, but intranasal route is quick onset |

| Nalbuphine | Nubain (IV only) | Ceiling analgesic effects | Some patients experience less reward than with mu opioids |

| Pentazocine | Talwin, Talwin NX (with naltrexone) (oral only) | Ceiling analgesic effects | Some patients experience less reward than with mu opioids; formulated with naltrexone due to IV abuse in 1960s |

Abbreviations: CR, controlled release; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; IR, immediate release; IV, intravenous; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartic acid.

FIGURE 6.

Opioids’ Analgesic Activity

Mu opioids block pain mainly by activating mu opioid receptors. An important site of opioid pain suppression is the dorsal horn (inset). Here, mu opioids (shown in gold) attach to receptors (dark blue), inhibiting peripheral fibers from transmitting incoming pain signals (blue arrow), and spinal neurons from receiving them. Simultaneously, signals (purple arrow) triggered by mu opioid activation in the brain further inhibit the responsiveness of spinal neurons. As a result of these actions, pain signals relayed up the spine (white arrow) are weakened or abolished.

Individuals vary in their analgesic responses and the side effects they experience with different mu opioids. The main reason appears to be that each mu opioid acts more strongly at certain mu subreceptors and more weakly at others, and people differ genetically in the proportions of the various subreceptors present in their systems (Mercadante, 1999; Pasternak, 2005; Thomsen, Becker, and Eriksen, 1999).

Kappa Opioids

Kappa opioid analgesics, though not widely used, provide analgesia through kappa opioid receptors (Table 2). Kappa opioids are usually antagonists at the mu receptors; they cannot be used in combination with mu opioids, as they reverse mu opioid analgesia and may cause withdrawal in physically dependent persons. Kappa opioid analgesics have a ceiling of analgesic effect and are appropriate for use in moderate, but not severe, pain.

Opioid Side Effects

Side effects of mu opioids are dose-related and include sedation, cognitive blurring, respiratory depression, meiosis (pupillary constriction), nausea, urinary retention, constipation, and reward. Except for constipation, side effects tend to be transient and generally resolve within a few days at a stable dosage. Side effects may reemerge with an increase in dosage.

Compared with mu opioids, kappa agonists have a lower incidence of side effects such as sedation, respiratory depression, and nausea. Reward appears less common as well, although some individuals do misuse these medications for euphoria. Dysphoria is a relatively common side effect of kappa agonists.

Effective treatments are available for most opioid side effects when they persist. Many studies have documented that cognitive and sedative side effects of opioids are negligible in most persons using a stable dose over a prolonged period of time. Therefore, most persons who use opioids on a long-term basis for analgesia may perform high-level mental and physical work without compromise of function (e.g., Gaertner et al., 2006; Zacny, 1996).

The possibility of opioid-induced hyperalgesia (increasing pain or pain sensitivity) must be considered when pain continues to worsen without any other identifiable cause in a patient using high doses. One possible cause of this phenomenon is that opioids may activate N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors, which has been shown to cause neuropathic pain experimentally. The relationship between opioid tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia is a subject of intense interest among opioid researchers and pain clinicians (Chang, Chen, and Mao, 2007).

Patients must sometimes be tapered off opioids when continued upward titration is not feasible due to increasing side effects, pain, or other concerns, and switching to another opioid does not help. Sometimes patients improve clinically with lower doses or cessation of opioids (Baron and McDonald, 2006). If pain increases during a taper from opioids, alternative approaches to pain management should be intensified.

Tolerance to Opioids

Tolerance is a state of adaptation in which exposure to a drug induces changes that result in diminution of one or more of its effects over time (American Society of Addiction Medicine [ASAM], 2001). Individuals commonly become tolerant to the analgesic effects and side effects of opioids; this should not be considered an indicator of addiction in the context of the pain treatment. Most often, tolerance to side effects such as respiratory depression, nausea, and sedation develops more rapidly than tolerance to analgesia, permitting doses to be escalated as necessary with appropriate monitoring to achieve effective pain control. Constipation, however, may be a persistent problem requiring specific treatment.

Tolerance to the opioid analgesia may be addressed in several ways. Often, the physician simply increases the dosage. However, if a patient appears to develop rapid or persistent tolerance to a particular opioid, or if persistent side effects occur at higher doses, switching to an alternative opioid may sustain or improve analgesia while alleviating the problematic effect. A caveat with this strategy is that rotation from methadone to other opioids does not routinely improve analgesia. It has been hypothesized that methadone is a “broader spectrum” opioid (i.e., activates a more complete spectrum of mu subreceptors; Pasternak, 2005) or that methadone maximally activates the opioid receptors to which it binds, such that there is a loss of relative opioid effect with substitution of other mu opioids, which decrease relatively the number of receptors activated (Kreek, 1973).

Opioid Physical Dependence

Physical dependence is a state of physiological adaptation that manifests in a drug-class-specific withdrawal syndrome that could result from abrupt cessation, rapid dose reduction, a fall in blood level, or administration of an antagonist (ASAM, 2001). Many medications produce physical dependence, including those that have potential reward effects, such as opioids or benzodiazepines, and some that do not, such as prednisone, tricyclic antidepressants, and many antihypertensive medications. Physical dependence on opioids, like tolerance, is common after continuous use for pain and, in this context, does not indicate addiction. Physical dependence and tolerance may or may not be present with misuse of or addiction to opioids; they do not, in and of themselves, indicate misuse or addiction.

Reward Considerations

The potential for patients receiving opioids for pain treatment to experience reward is a critical factor to consider when assisting patients with co-occurring pain and substance use disorders. A clear understanding of the potential issues that drive opioid reward will allow addiction professionals to better understand their patients’ subjective experiences of these medications and to think through options for reducing negative impact.

Mechanisms of Reward

Opioids produce reward by binding to GABAergic interneurons that normally inhibit dopamine production in the limbic reward system and preventing them from doing so (Hurd, 2006). The resulting increase in dopamine and the cascade of secondary effects produce feelings of reward. These feelings may occur along with analgesia when opioids are used for pain and are not in themselves harmful. In some contexts, particularly terminal illness, they may, in fact, be a valued side effect. However, when euphoria becomes the focus of the use of opioids, especially in a person with addictive disease, it may undermine pain treatment and become a problem in its own right. Understanding how to limit opioid reward effects therefore may be helpful.

Most of what is known about the mechanisms that determine reward intensity derives from addiction literature; this information may, however, also apply and provide some guidance in clinical pain treatment settings. Relevant considerations include the rate of increase in brain levels of a drug, blood levels of the drug relative to individual tolerance, fluctuations in drug blood levels, and the specific receptor profile of the drug with respect to individual receptor variability.

Rate of Increase

Both animal drug self-administration studies and human drug-liking studies have demonstrated that reward increases with the rate of rise in drug blood levels; the faster the influx of drug into the blood, the better the rush or high (Marsch et al., 2001). A recent study to determine which properties of prescription opioids make them more attractive for purposes of getting high supported the speed of onset as a key value (Butler et al., 2006).

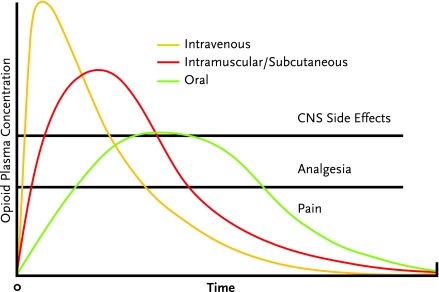

In the setting of therapeutic opioids, the intravenous route of administration causes a more rapid rise in blood levels and is expected to provide more euphoria than the oral route. Intramuscular and subcutaneous administration provides an intermediate effect. Among opioids given orally, those with an inherently slower time to peak effect (such as methadone or levorphanol [Levo-Dromoran]) are expected to produce weaker reward effects than opioids with relatively rapid onset, such as immediate-release oxycodone (in Percocet or OxyContin), hydrocodone (in Vicodin or Lortab), or hydromorphone (Dilaudid).

Peak Blood Level Attained

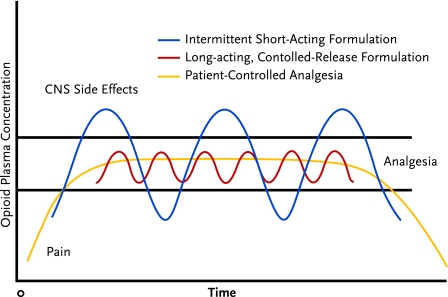

The higher the opioid blood level relative to the individual’s tolerance for the drug, the greater the reward. An opioid-naive individual with little or no tolerance may experience euphoria with a drug blood level that would cause no significant reward effect in a more tolerant individual. A dose of an opioid given intravenously achieves a higher peak in blood level than the same dose administered by the oral route; the effect with subcutaneous and intramuscular administration is, again, intermediate (Figure 7). As the rise in the blood level of a drug is associated with onset of euphoria, stable levels generally produce less euphoria than intermittently rising and falling levels. This key principle underlies the effectiveness of methadone maintenance therapy for opioid addiction. It also follows that continuous intravenous infusion of an opioid will likely trigger less reward than intermittent boluses, and controlled-release opioids (used by the intended route at the intended time interval) or intrinsically long-acting opioids (such as methadone or levorphanol) should be less rewarding than frequently dosed short-acting medications.

FIGURE 7.

Routes of Opioid Administration

The appropriate route of opioid administration depends on the clinical goal. The intravenous route yields the swiftest but briefest pain control, compared with oral and intramuscular/subcutaneous administration, and has the most central nervous system (CNS) side effects. Oral administration maximizes the duration of analgesia and minimizes CNS side effects, but has the longest time to onset of relief.

An exception to this rule is patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), which is not expected to provide significant reward because the incremental doses are very small and spaced at intervals that do not permit a rapid, high rise in the blood level of the drug (Figure 8). However, when persons with an active addiction to opioids receive PCA or any intravenous infusion, close supervision is critical to ensure that there is no tampering with the system.

FIGURE 8.

Schedule of Opioid Administration

Both controlled-release opioids and patient-controlled opioid analgesia (PCA) can avoid the central nervous system (CNS) side effects and periods of breakthrough pain that may occur during cycles of intermittent short-acting opioid administration. PCA provides the steadiest level of pain control.

Receptor Effects

As previously discussed, mu opioids are more likely to cause reward than kappa opioids. Emerging knowledge of mu opioid subreceptors indicates that individuals may experience varying reward effects as well as unequal analgesic effects from a given opioid. Theoretically, this would correlate with the clinical fact that patients treated for opioid addiction identify different opioids of choice.

Interference of Pain With Reward

Some research suggests that people feel less euphoria if they are in pain when given opioids and that, therefore, clinicians need not be as concerned about reward in the context of pain treatment (Zacny et al., 1996). This hypothesis is supported by reports from many patients who say that opioids relieve their pain without any psychic effects. Further, many patients experience dysphoria or other aversive feelings, rather than euphoria, when given opioids for their pain.

Modulation of Reward Through Drug Selection and Dosing

Many experts recommend that patients who require opioid therapy to manage around-the-clock pain be placed on long-acting medications. The experts believe that, in these circumstances, long-acting opioids provide more consistent pain relief, more convenience, reduced clock watching for pain relief, and theoretically, less reward. In addition, there is concern that fluctuating blood levels associated with short-acting opioids may produce intermittent physiological withdrawal in patients who become physically dependent—as most do who use these medications continuously. Withdrawal could actually increase pain through arousal of the sympathetic nervous system and increasing muscular tension.

Despite these theoretical advantages of long-acting or sustained-release opioids, few studies have directly compared reward effects or misuse-related outcomes in persons prescribed different opioids or different formulations of a specific opioid for pain. One such study found no significant difference in misuse among patients receiving short-acting hydrocodone and others taking longer acting hydrocodone (Manchikanti et al., 2005). The theoretical advantages of long-acting opioids, therefore, must be weighed against other clinical indications. For example, persons who experience intermittent severe pain may do better with intermittent short-acting opioids to cover periods of pain, rather than long-acting medications that would provide continuous opioid receptor stimulation even in the absence of pain.

Most controlled-release opioids can have immediate-release effects through chewing, crushing, snorting, or extracting and injecting. Most persons who use prescription opioids to get high do, in fact, alter them in some way (Passik et al., 2006a, 2006b). Currently, many pharmaceutical companies are pursuing abuse-resistant formulations, though it is not likely that any system will be entirely abuse-proof.

If short-acting opioids are used for intermittent pain, or with a longer acting medication for incident or crescendo pain, there may be advantages to providing these drugs on the basis of timing or activity rather than perceived pain severity. This practice may serve both to preempt pain and to avoid pairing the subjective experience of pain with a potentially reinforcing reward. Theoretically, such a pairing might increase the experience of pain, justifying increased opioid dosing in persons vulnerable to addiction or addiction relapse and leading to a cycle of increasing pain and increasing opioid use and distress (Højsted et al., 2006).

In time-contingent dosing, a patient who routinely develops pain in the afternoon and evening, for example, might receive a dose of a short-acting opioid at noon and 5 p.m. only. In activity-contingent dosing, someone who has unmanageable pain in association with certain valued activities, such as sitting on hard wooden pews through a church service, might be instructed to take medication 30 minutes before the activity.

Although concerns regarding drug reward may be relevant for persons at risk for opioid misuse or addiction, such concerns should not deter effective and immediate treatment when opioids are required for relief of significant acute pain. The long-term outcome of addiction is not likely to be strongly affected by the use of the indicated medications in the short term (Ballantyne, 2007).

Differential Diagnosis of Opioid Misuse in Pain Treatment

Patients misuse opioids for a variety of reasons that are associated with a wide range of implications (Table 3). It is important to distinguish clinically between different causes of opioid misuse in order to address each case appropriately. The most common cause, probably, is simply misunderstanding how opioids are supposed to be used; clear written instructions can reduce this type of misuse. Patients may misuse opioids prescribed for pain to obtain relief from depressed feelings, anxiety, insomnia, or discomforting memories; these patients usually will have a greater benefit from more specific treatments. Patients who have become physically dependent on opioids provided for pain may continue to use the drugs once the pain has resolved in order to avoid withdrawal symptoms; tapering of opioids can usually eliminate dependency without significant withdrawal distress.

TABLE 3.

Differential Diagnosis of Misuse of Analgesic Opioids

|

Patients sometimes exhibit distress and engage in behaviors aimed at obtaining more medication because their pain treatment is inadequate (Weissman and Haddox, 1989). This scenario has been called “pseudoaddiction,” because it is easy to misinterpret the behaviors as indications of addiction rather than as reflections of their true underlying cause—a desire for analgesia (Weissman and Haddox, 1989). The solution is to provide adequate pain control, with or without opioids.

A subset of patients who have a biogenetic vulnerability and who use opioids electively in a manner that induces euphoria will trigger addiction. This leads to continued compulsive use of opioids in a potentially self-destructive manner that poses significant personal risk. A final type of opioid misuse occurs when individuals divert opioids from therapeutic channels to share or sell them for recreational use, for treatment of untreated pain in others, or for financial gain. Such diversion creates a significant public health risk.

Incidence of Addiction in Pain Treatment

The actual rate of occurrence of opioid addiction in the course of opioid therapy for pain is uncertain, as no studies have examined this issue prospectively. Most studies that measure substance misuse have excluded persons with addictive disorders (Furlan et al., 2006).

Some studies suggest that a relatively high percentage of persons treated for opioid addiction first took the drugs in the course of pain treatment. For example, a recent study (Passik et al., 2006a) found that 47 percent (51 of 109) of persons presenting for treatment of oxycodone addiction had their first exposure to opioids through a prescription for pain, and 31 percent of this subgroup had prior histories of problems with alcohol or another substance. This study did not comment on the participants’ biogenetic risks as reflected in their family histories of addiction and thus shed no light on whether these apparent de novo addictions occurred in the presence or absence of identifiable biogenetic risk. No case reports have been identified of patients with no known family or personal risk factors presenting with de novo addiction to opioids related to use of prescription opioids for pain, though it certainly may occur.

Studies of the incidence of addiction occurring in the context of pain treatment have been variable in quality and methodology, and have tended to examine a wide spectrum of “aberrant drug behaviors” rather than clear diagnoses of addiction. The prevalence of identified misuse of opioids that are prescribed for pain varies widely in different studies, from 1 to 38 percent (Adams et al., 2001; Ives et al., 2006; Katz and Fanciullo, 2002; Michna et al., 2007). The etiology of addiction likely involves an interplay between opioids’ reward effects; the individual’s biogenetic vulnerability; and modulatory factors such as the presence of pain, stress, and the psychosocial context of use (Hurd, 2006; Kahan et al., 2006).

Identification of Addiction in Pain Treatment

Patients who use opioids on a long-term basis for the treatment of pain can easily meet five of the seven criteria for substance dependence listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) without manifesting the craving or behaviors that most addiction professionals regard as the core phenomena of addiction (Savage, 1993; Sees and Clark, 1993; Table 4). Thus, when DSM-IV-TR criteria are used to assess for addiction in the context of pain, clinicians must look for two critical criteria: (i) important functions or valued activities given up because of drug use, and (ii) continued use despite knowledge of persistent physical or psychological harm because of use.

TABLE 4.

Applicability of DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Addiction to Patients Receiving Opioid Analgesia

| CRITERION | APPLICABILITY |

|---|---|

| Tolerance | Limited—tolerance is expected with prolonged analgesic use |

| Physical dependence/withdrawal | Limited—dependence is expected with prolonged regular analgesic use |

| Used in greater amounts or longer than intended | Limited—emergence of pain may demand increased dose or prolonged use |

| Unsuccessful attempts to cut down or discontinue | Limited—emergence of pain may deter dose taper or cessation |

| Much time spent pursuing or recovering from use | Limited—difficulty finding pain treatment may drive time spent seeking analgesics |

| Important activities reduced or given up | Valid criterion—activity engagement is expected to increase, not decline, with pain treatment |

| Continued use despite knowledge of persistent physical or psychological harm | Valid criterion—no harm is anticipated from analgesic opioid use for pain |

Abbreviation: DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., Text Revision (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

ASAM, the American Pain Society, and the American Academy of Pain Medicine have developed a definition of addiction that reflects current clinical and scientific understanding and facilitates assessment for addiction in diverse medical contexts, including pain treatment (Table 5). The definition lists specific behavioral indicators whose presence may prompt further assessment for addiction in the context of pain treatment. Many patients with pain who use opioids as a component of care will demonstrate one or more of these behaviors from time to time for reasons not related to addiction, but a persistent pattern of the behaviors suggests the need for a fuller evaluation.

TABLE 5.

Criteria Suggestive of Misuse or Addiction in Patients With Pain

| ASAM-APS-AAPM BEHAVIORAL CRITERIA | EXAMPLES OF SPECIFIC BEHAVIORS IN OPIOID THERAPY OF PAIN |

|---|---|

| Impaired control over use, compulsive use | Frequent loss/theft reported, calls for early renewals, withdrawal noted at appointments |

| Continued use despite harm due to use | Declining function, intoxication, persistent oversedation |

| Preoccupation with use, craving | Nonopioid interventions ignored, recurrent requests for opioid increase/complaints of increasing pain in absence of disease progression despite titration |

The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), American Pain Society (APS), and American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM) define addiction as a primary, chronic, neurobiological disease with genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestations characterized by one or more of the behaviors listed above (ASAM, 2001).

The patient who is prescribed opioids for pain and who reports reasonably sustained pain control; demonstrates improving or stable function; participates in other recommended evaluations or treatments; discusses the need for dose increases at regularly scheduled appointments; has no, or rare, issues with prescription; and exhibits no evidence of other drug or alcohol misuse is not likely to be addicted to opioids. However, persons who divert medications for sale may sometimes present as model patients.

Clinicians must be vigilant in looking for patterns of behavior that may suggest diversion. These include known contact with a drug-using population, inability to produce the remainder of a partially used prescription when asked, noncompliance with other treatment recommendations, preference for drugs with a high street value, preference for nongeneric drugs, and negative urine screens when the drug should be detectable in the urine based on dosage and pharmacology.

Clinical Management of Opioids in Persons With Substance Use Problems

Addiction professionals can make valuable contributions to safe and desirable outcomes when individuals in their care receive opioids as a component of treatment for acute or chronic pain. The addiction professional’s role varies in different settings but often includes providing support for recovery and helping patients minimize their risk of misusing medications through cognitive, behavioral, and other strategies. Cognitive-behavioral and Twelve-Step approaches may also be helpful in the management of pain per se—sometimes directly improving pain control and at other times helping to reduce anxiety and fears that might otherwise exacerbate perceptions of pain (Turner, Holtzman, and Mancl, 2007). An understanding of the principles of opioid therapy of pain, when integrated with the clinician’s existing counseling skills, makes a good basis for assisting patients in pain management.

Opioids in Acute Pain

Principles of Care

When significant pain can be anticipated, such as after elective surgery or with intermittent relapsing pain syndromes (e.g., sickle cell anemia or pancreatitis), it is helpful for patients with known addictive disease or with physical dependence on licit or illicit opioids to develop a pain treatment plan in advance and to document this plan in the medical record. The objectives are to ensure that addiction or physical dependence will be addressed as a co-occurring medical issue, that issues such as tolerance and increased medication requirements will be appropriately accommodated, and that the patient will be treated respectfully.

Several key principles guide effective opioid therapy of acute pain in individuals with physical dependence on opioids:

The patient’s established daily doses of chronically used opioids will not provide analgesia for additional acute pain, and additional analgesia, either opioid or nonopioid, must be provided;

Persons who are physically dependent on opioids usually also have tolerance and require higher doses at more frequent intervals than nondependent persons;

Prescribing scheduled, long-acting, or continuous opioids, while reserving the use of pro re nata (prn) medication primarily for dose titration, provides analgesia and avoids compelling the patient to request opioids frequently, which may be misinterpreted as drug seeking;

For individuals in recovery from addiction, intensification of recovery activities supports safe use of therapeutic opioids and may reduce the risk that medical challenges and opioid therapy will trigger relapse; and

In periods of medical challenge (e.g., illness, surgery, trauma), patients with active addiction may be especially amenable to entering addiction treatment.

Methadone-Maintained Patients

Clinical consensus holds that patients receiving methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) of addiction should generally continue their daily dose of methadone and receive a different medication for acute pain (Scimeca et al., 2000). This practice keeps the purpose of each medication clear and allows simple tapering of the pain medication as acute pain resolves. In addition, there have been case reports of opioid withdrawal upon cessation of methadone and substitution of other opioids. The reasons for this phenomenon are unclear but may be related either to methadone’s putative action on a broad spectrum of mu subreceptors or to its full agonist properties (Inturrisi, 2005). Although methadone can be titrated for acute pain, doing so requires expertise and careful patient monitoring, because the medication’s slow onset and long half-life not only make it difficult to titrate rapidly and effectively for pain, but also create a potential for unexpected high blood levels and overdose.

Pain treatment providers should confirm the patient’s daily maintenance dose of methadone with his or her treatment program. If this is not possible, the physician should prescribe a quarter of the reported regular daily dosage at 6-hour intervals with observation for sedation to ensure safety, as some maintenance doses may be lethal in less tolerant patients. If intravenous dosing of methadone is required, it should be given at half of the usual oral dosage.

Buprenorphine-Maintained Patients

Strategies for managing acute pain in individuals taking buprenorphine for the treatment of addiction are emerging as experience accumulates. Buprenorphine binds avidly to opioid receptors and thus tends to block the action of other opioids that may be provided for pain. As a result, it is difficult, though not impossible, to obtain analgesia by adding another opioid to buprenorphine. In addition, buprenorphine has kappa opioid receptor antagonist activity that may interfere with the actions of other opioids (Vadivelu and Hines, 2007). When individuals being treated with buprenorphine face surgery or other predictably pain-generating procedures, it is often advisable to discontinue buprenorphine a few days beforehand. Carefully dosed methadone can be added if withdrawal symptoms emerge after the patient stops taking buprenorphine or if continued opioid maintenance therapy is needed to block craving while waiting for surgery.

If a patient on buprenorphine develops pain requiring opioid therapy owing to an accident or other unexpected event, mu opioids can usually be aggressively titrated to sufficiently high doses to overcome the buprenorphine blockade. The intravenous use of an opioid such as fentanyl, which also binds very tightly to mu opioid receptors, is often recommended. Opioid titration for acute pain in this setting should be done by an experienced clinician with an intravenous catheter; an opioid antagonist such as naloxone should be on hand, and the patient should be closely monitored.

Alternatively, a patient’s low maintenance dose of buprenorphine (e.g., 2 to 8 mg per day) can sometimes be increased and given at 6-hour intervals to control pain. However, because buprenorphine doses of 16 to 32 mg per day saturate the mu receptors while only partially activating them, buprenorphine’s analgesic effect may have a ceiling. It is not clear whether doses higher than 16 to 32 mg per day will control more severe pain. Understanding of the analgesic properties of buprenorphine is still evolving.

Opioids in Chronic Pain

Some experts suggest that when opioids are a necessary component of chronic pain treatment, a set of universal precautions be used in managing all patients. The rationale for this recommendation parallels that for the use of universal precautions in infectious disease settings: The risk that an individual patient will misuse opioids cannot be reliably predicted; the misuse of opioids has potentially serious consequences for both the patient and the prescriber; and applying precautions only to selected patients risks stigmatizing those patients. Therefore, it is argued that, for all patients, care providers should:

Conduct a careful assessment guided by a differential diagnosis of the pain;

Assess psychological and substance use issues;

Obtain informed consent for treatment;

Reach a clear treatment agreement;

Set up a trial treatment period with clear goals;

Assess and periodically reassess pain level (Gourlay, Heit, and Almahrezi, 2005), function, and other salient issues; and

Document care thoroughly.

Most clinical experts and regulatory boards agree that it is important to screen all patients for risk of opioid misuse before initiating long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain (ASAM, 2001). Standard assessment of substance use history, when performed in medical settings, most often includes questions about past and present alcohol, tobacco, and street drug use, including treatment, as well as screening with “cutting down, annoyance by criticism, guilty feeling, and eye-openers” (CAGE), Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST), or other common instruments (Brown and Rounds, 1995).

A number of screens to assess the risk of medication misuse in pain treatment settings are being developed (Akbik et al., 2006; Friedman, Li, and Mehrotra, 2003). Two that appear promising are the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients in Pain, which has been validated as a 14- and 20-question screen and is now undergoing testing in a shorter form, and the Opioid Risk Tool, a user-friendly, five-question screen that discriminates well between high- and low-risk patients (Webster and Webster, 2005). An important caveat concerning these tools is that none has been specifically validated for use in populations with substance use disorders. During treatment for pain, clinicians can use measures such as the Addiction Behaviors Checklist to track behaviors of concern (Wu et al., 2006).

Adapting the Structure of Care to Match Risks

When a risk of opioid misuse is perceived, individualizing and tightening the structure of clinical care beyond universal precautions may enhance safety. In this situation, it is helpful to think in terms of five domains of structure:

Setting of care (primary versus specialty care, clinical care team membership);

Selection of treatment (risk/benefit assessment of specific medications and treatments);

Supply of medications (controls on and amounts of medications dispensed);

Supports for recovery (implementation and documentation of recovery activities); and

Supervision and monitoring (frequency of visits, toxicology screens, pill counts, other).

Although there is some overlap in these areas, attention to each ensures that the clinician has thought through the best options of care for the particular patient.

Setting of Care

Some patients with pain are best managed in a primary care setting with support from specialists; others are best managed in a specialty care setting by a clinician with specific skills in an area of need, for example, a pain specialist, addiction specialist, or psychiatrist (Gourlay, Heit, and Almahrezi, 2005). There are advantages and disadvantages to each setting. Primary care providers tend to have broader and more longitudinal knowledge of the patient and are in a better position to integrate pain care with other medical care issues. Specialists tend to have a greater depth of knowledge and expertise in the management of a particular aspect of the patient’s medical care and may provide better management when a particular problem is prominent, such as addiction or psychiatric instability.

Many variables may contribute to the determination of the best setting of care for an individual patient. No formula can dictate which professional should manage a particular clinical pain problem, but the consideration of a number of variables may be helpful in decision making (Table 6). The most appropriate management setting may change as the patient’s presentation changes.

TABLE 6.

Proposed Algorithm for Determining the Appropriate Setting for Pain Management

| CLINICAL PARAMETER | GENERALIST CARE ↔ SPECIALIST CARE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Etiology | Clear, straightforward etiology of pain | Uncertain etiology, but some physiological clues or a suggestive pattern of pain | Etiology unknown, no physiological clues, no familiar pattern, or complex treatment needs |

| Psychiatric Disorder | No history of psychiatric disorder | Stable, well-compensated psychiatric disorder | Psychiatric instability |

| Addiction | No history of substance abuse or addiction | In recovery or history of major substance abuse | Active addiction, current illicit use |

| Social Support | Good social support | Some social discord or challenging social net | Isolated, major social distress, destructive associates |

| Activity Engagement | Rich work or avocational life | Some engagement with meaningful activities | No satisfying work, recreation, or other activities |

Selection of Treatment

The selection of pain treatments, as with most medical treatments, is usually based on a determination of which would likely provide the most benefit for the patient with the least risk. The patient’s preferences and the care provider’s skills and clinical opinions are also important factors that shape treatment selection. In a patient with relapsing opioid addiction, cognitive limitations, or certain psychiatric disorders, opioid analgesics may represent a greater risk than for persons without these conditions. In such patients, a treatment that is relatively invasive or expensive might be preferable early in the course of pain treatment, when other patients might receive instead a trial of opioid therapy. For example, patients with unilateral radiculopathy usually receive a trial of pharmacological therapy, including opioid therapy, prior to consideration of spinal cord stimulation (SCS), as the latter is considerably more invasive and costly. However, SCS might justifiably be tried first when a patient has relapsing opioid addiction, because the addiction shifts the risk/benefit/cost balance. Similarly, knowing that a patient experiences reward from short-acting opioids (referred to by one recovering patient as “dancing with an old lover”) could warrant the prompt choice of slow-onset, long-acting opioids, although they cost more and typically are given only after the shorter acting opioids fail to control pain.

Supply of Medications

Making opioids available in quantities that relieve pain but do not invite misuse is a key factor in successful opioid therapy of pain in persons with substance use problems. The number of units of opioid medications available to the patient and the frequency with which they are dispensed are two variables that can be controlled.

In current practice, patients commonly receive a month’s supply of analgesic opioids, and some clinicians provide stable patients who have no detected risks with up to a 3-month supply. For persons who have addictive disorders or tend to overuse medications for other reasons, however, it is often prudent to dispense smaller quantities of medications more frequently, for example, weekly or even daily. This practice can help a patient avoid overuse (“a little extra won’t hurt and may help”), because it is easier to see that taking two of seven one-a-day tablets will deplete the supply before week’s end than it is to see that taking five rather than the prescribed four tablets per day will exhaust a supply of 120 before month’s end.

Frequent dispensing of small doses can also preserve safety by ensuring that persons prone to harmful misuse do not have a potentially lethal supply available. Applying a signed and dated transdermal fentanyl patch in the physician’s office every 72 hours may be a helpful procedure for some patients considered at risk. However, it is important to note that all long-acting medications can be altered to cause release of the full dose immediately, and injection or transmucosal use of the opioid contained in any 3-day fentanyl patch could be lethal to most persons. In the final analysis, the only method that fully protects a patient who is at risk for major overuse is keeping the total dose dispensed sub-lethal.

Frequent dispensing can be done by a pharmacy, a clinician’s office, or a trusted surrogate, such as a family member. In the last instance, care must be taken to avoid potential resentment and conflict over the surrogate caregiver’s carrying out of his or her charge.

Supports for Recovery

Many persons who are recovering from an addictive disorder and require opioids for pain treatment benefit from active cultivation of their recovery. What constitutes a meaningful array of recovery activities varies between individuals but may include, for example, attendance at self-help meetings, close interaction with a sponsor, work with a counselor, or active participation in a faith community. Addiction professionals may provide an important service to patients and their pain treatment providers by recommending ways to enrich recovery and by supervising the recovery plan while patients are using opioids for pain. Persons with other conditions that may put them at risk for misuse of medications, such as psychiatric disorders or cognitive impairment, generally will benefit from engagement of appropriate professionals to assist in management of or accommodation to their illness.