Abstract

As described by the authors, a recovery-oriented system of care for drug-abusing criminal offenders is one that provides for continuity of treatment, using evidence-based interventions at every stage as clients progress through the justice system. Treatment Alternatives for Safe Communities of Illinois has partnered with criminal justice and treatment programs to establish a basic recovery-oriented system, with programs that span pre-adjudication, probation or incarceration, and parole.

For most addicted individuals, sustained recovery requires long-term involvement in abstinence-directed activities and support networks (Brewer, 2006; Vaillant, 1995). Accordingly, clinicians and researchers have begun to develop recovery management models that incorporate interventions for use across the many stages of personal growth, setbacks, and transformation that individuals pass through on the way to long-term recovery (White, Kurtz, and Sanders, 2006). In our view, these approaches will realize their full potential only if they can be integrated into a broader recovery-oriented system of care. Such a system will match treatments and support services to individual needs, provide an appropriate mix of incentives and sanctions, engage clients in treatment with beneficial effects that are cumulative across treatment episodes, and link clients to ongoing support in the community. It will:

coordinate the delivery of services throughout the recovery process, from detoxification and treatment to ongoing support for a productive, drug-free life in the community;

coordinate ancillary services, such as employment and housing assistance; and

help clients achieve a phased integration or reintegration into employment, education, and family relationships based on their stage in recovery (McLellan et al., 2005).

A full recovery-oriented system will also feature programs attuned to the situations and special needs of various subpopulations. Individuals who begin or continue recovery while under criminal justice supervision make up one of the largest of such subpopulations. More than two of every three individuals tested at 39 sites by the National Institute of Justice’s Arrestee Drug Monitoring Program in 2003 had illegal substances in their systems when they were arrested (Zhang, 2004).

Between 56 and 66 percent of the 2.2 million people incarcerated in U.S. prisons and jails in 2005 were estimated to have a diagnosable substance use disorder (James and Glaze, 2006). Of the 5 million individuals on probation or parole in 2006, 27 percent of probationers had drug violations as their most serious offense, and 37 percent of parolees had served a sentence for a drug offense (Glaze and Bonczar, 2007). A recovery-oriented system for this population must balance inter-linked issues of public safety and public health to facilitate clients’ recovery from criminality as well as drug abuse. Together with fulfilling the general requirements for a recovery-oriented system, it must:

hold clients responsible to both the criminal justice and treatment systems;

integrate each client’s recovery into a legal framework and identify the most critical points of intervention to satisfy both community safety and case-processing needs;

provide access to evidence-based drug treatment interventions suitable for individual offenders at each stage of their recovery and justice processes; and

ensure that clients do not receive isolated interventions and fragmented care, but coherent care that builds cumulatively toward sustained recovery.

Treatment Alternatives for Safe Communities (TASC) of Illinois is one of numerous TASC organizations founded since the 1970s to reduce criminal recidivism by linking offenders on probation and parole to drug abuse treatment and other services in the community. As one of the oldest and currently the largest of these organizations, Illinois TASC every year reaches more than 20,000 probationers, parolees, and other offenders statewide. Our operational model incorporates the critical elements and clinical components specified by national TASC; our size and resources have enabled us to extend and elaborate this model. Over the years, we have worked with partners in the criminal justice and treatment systems to develop a comprehensive, unified, statewide model that has the essential features of a recovery-oriented system for substance-abusing offenders. We propose that an independent mediating agency, on the scale of Illinois TASC, is vital to the interface between criminal justice and treatment systems that is a prerequisite to recovery-oriented care. We then describe the Illinois model.

IMPASSE AND ANSWER

The importance of integrating substance abuse treatment with criminal justice activities has been evident for some time (e.g., Center on Evidence-Based Interventions for Crime and Addiction, 2007; DeLeon, 2007; Taxman and Bouffard, 2000). In terms of infrastructure, neither a treatment system nor a criminal justice system is equipped to manage a recovery-oriented system of care for drug-abusing offenders. Treatment systems lack the ability to remain in contact with individual clients over the extended periods of time that stable recovery and community reintegration often require. Although justice systems track people for much longer, they are segmented, and each component maintains contact during only one stage of an offender’s progress through the system. Hence, police, courts, drug courts, jails, prisons, and parole agencies each may be able to support individual episodes of care, but none has the ability to address recovery from addiction as a years-long process. Moreover, their different mandates, legal frameworks, authorities, and funding limit their ability to coordinate with each other to the degree necessary to support continuity of care.

To date, the most successful and widely accepted example of integration between justice and treatment has been the growing use of drug courts. These special venues effectively engage and retain offenders in substance abuse treatment (Marlowe, DeMatteo, and Festinger, 2003); they are especially suited for individuals with significant treatment needs (Marlowe, Patapis, and DeMatteo, 2003). Drug courts are a positive development, but they are an exception to what has generally been a checkered history of cooperation between justice and treatment. Although both systems may recognize that their objectives of public safety and client recovery are mutually reinforcing—and to a significant extent interdependent—they often have difficulty coordinating the use of their respective tools of social control and clinical intervention. Structural and cultural differences hinder communication and produce friction, especially when events such as relapse to substance abuse occur that elicit potentially discordant responses from the two systems.

Based on our experience at Illinois TASC, we believe that an independent agency to manage recovery-oriented care is an optimal answer to this impasse. The primary objective of such an agency and measure of its success must be the prevention of recidivism, as the goal of public safety takes precedence over that of client recovery in instances where the two may come into conflict. The agency’s primary function would be to leverage judicial authority and clinical interventions in an optimal way to induce lasting behavioral change. By building strong relationships with both justice and treatment, an independent agency can mediate cultural differences, emphasizing the complementary nature of the goals and methods of the two systems, and maintain continuity of care as clients proceed from one to another.

A DEVELOPING RECOVERY-ORIENTED SYSTEM

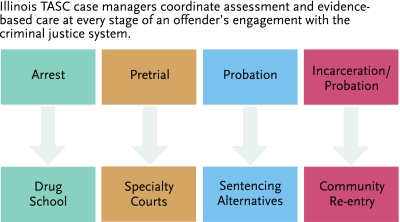

Illinois TASC provides individual case management for offenders with substance use disorders throughout Illinois. The Illinois TASC organizational structure intersects with every criminal justice component, including courts, jails, juvenile and adult prisons, and probation and parole agencies. Illinois TASC has worked for many years with the State of Illinois and Cook County, which encompasses Chicago, to develop and implement services and treatment programs for clients under supervision by each component (Figure 1).Our goal is to create a complete recovery-oriented system that offers appropriate services to offenders with all types and intensities of drug involvement in all stages of recovery anywhere in the criminal justice system. Although existing programs do not yet match the scale of need, the infrastructure and programs have been established to serve clients in each phase of criminal justice processing:

FIGURE 1.

Criminal Justice System Components and Corresponding Illinois TASC Programs

Pre-Adjudication—The Cook County State’s Attorney’s Drug Abuse Program (SADAP): SADAP provides drug-involved arrestees who have limited criminal records with a basic drug education curriculum that includes information on the science of drug addiction and the criminal justice consequences of drug abuse. Successful graduates have their charges dismissed. Among defendants who register for the program, 80 to 90 percent graduate, and 83 percent of graduates have no arrests for drug crimes in the 3 years after program completion (outcomes comparisons here and below are based on unpublished Illinois TASC administrative data). Illinois TASC coordinates program logistics, such as location, dates, and time; communicates expectations and benefits to participants; monitors participants’ attendance; and reports outcomes to all court personnel, including state’s attorneys, private attorneys, public defenders, and/or probation officers.

Adjudication and Sentencing—Cook County Mental Health Court (MHC):This program diverts offenders with mental illness into a structured probation program with mandated services that are supervised by a judge. The MHC’s basic premise is that mental health and substance abuse treatment will help clients escape the cycle of addiction, arrest, and conviction. Illinois TASC works with the MHC to assess clients prior to sentencing, coordinate their enrollment in mental illness–substance abuse programs and other care, and monitor their progress. Unlike many specialty courts, the Cook County MHC accepts clients with lengthy felony arrest and conviction histories. It has been very successful in reducing crime and hospitalizations within this high-risk population: Although 45 percent of all felony offenders in Cook County are rearrested on new felony charges during their probationary period, the figure for those under MHC supervision is only 20 percent. MHC participants averaged 12 days per year in custody while in the program, compared with 112 during the year before their arrest.

Adjudication and Sentencing—Drug Court: In several Illinois jurisdictions, drug courts team with the State’s Attorney’s Office, Public Defender’s Office, Adult Probation Department, Illinois TASC, and agencies providing treatment and recovery services. Substance abuse treatment, mandatory drug testing, comprehensive recovery services, and intense supervision are combined for drug court participants. Illinois TASC provides case management, including recovery coach and trauma support services, in addition to placement and monitoring in substance abuse treatment.

-

Probation—Treatment Alternatives Via Designated Program: Perhaps the greatest potential for beneficial change through a recovery-oriented system of care lies with the millions of Americans who are sentenced to probation for nonviolent, drug-related crimes. In Illinois, the legislature has provided for access to treatment as an alternative to prison for nonviolent offenders with substance abuse or dependence disorders. Under the statute, Illinois TASC assesses defendants to determine whether they have a substance use problem related to their criminal activity. Those who meet legal and clinical criteria may receive probation with TASC supervision. In fiscal year 2008, Illinois TASC assessed approximately 6,000 defendants and made 4,000 placements into treatment, followed by ongoing case management. Felony probationers in Cook County who received treatment and TASC supervision were less likely than other probationers to be rearrested while under supervision—31 percent compared with 49 percent.

AndrewWard/©Life File Prison and Probation—The Sheridan Model for Integrated Recovery Management: To date, this program most fully exemplifies the recovery-oriented principle of continuity of care across transitions in offender status. Sheridan engages participants upon their entry into the prison system and continues to work with them until they complete parole. It serves more than 1,000 inmates at any given time, providing substance abuse treatment, education, employment coaching, and vocational training. Illinois TASC provides prerelease planning and post-release case management services in the community, and it coordinates with parole authorities to monitor treatment compliance and ongoing recovery (Illinois Department of Corrections, 2006). Sheridan inmates who successfully completed aftercare in the community were 67 percent less likely to return to prison than a group of parolees with similar characteristics and criminal histories who did not receive aftercare (Olson et al., 2006).

MANAGING RECOVERY, ONE BY ONE

The point persons in Illinois TASC’s operations are our front-line case managers. They are a cadre with diverse backgrounds; some have bachelor’s or master’s degrees, others have criminal justice or addiction training, and some are in recovery. Each Illinois TASC case manager works closely with the courts, probation agencies, and parole officers to create an individualized case management plan for each client. The plan includes assistance with the spectrum of needs—for example, HIV infection and other health issues, documentation, employment— that can affect recidivism and relapse. With respect to substance abuse, the case manager’s role is to weave together correctional and substance treatment agendas, ensuring that interventions are coordinated and timed for maximum long-term effectiveness. Prior to a client’s release on probation or parole, the case manager assesses the client’s risks for criminality and drug abuse with instruments such as the Texas Christian University Drug Screen and the Client Evaluation of Self and Treatment with Criminal Thinking Scales (see www.ibr.tcu.edu).

To the extent possible, the case manager assigns each client to a provider that has demonstrated competency in treating individuals with the client’s particular constellation of issues. For example, a client may go to a provider that specializes in treating adults or adolescents, individuals with mental illness, or those with more or less entrenched criminal lifestyles. To facilitate appropriate placement, Illinois TASC collects information and outcomes data from treatment providers throughout the State and develops long-term partnerships with those that use evidence-based practices and have demonstrable records of effectiveness.

Together, the case manager, justice entity, and treatment provider formulate the specific treatment and recovery approach. The case manager’s primary function in these conversations is to mediate; he or she explains the goals and methods of the treatment provider to the justice partner in justice language and those of the justice partner to the treatment provider in treatment language. Illinois TASC’s independent status ensures that the case manager is perceived as committed equally to justice and treatment and thus a trustworthy intermediary. The aim of the recovery plan is to deploy the combined powers of social control and clinical intervention optimally to bring about prompt, complete, and long-lasting reduction in criminality and substance abuse. The plan determines the type and intensity of treatment the client will receive; in addition, it stipulates measures to be taken in case of client infractions. Usually, all parties understand that relatively mild relapses are not unusual early in the recovery process and often are better treated as intervention opportunities rather than triggers for immediate incarceration.

The case manager maintains periodic contact with the client throughout the client’s term of justice supervision, linking him or her to new services (e.g., housing or employment) as the client’s progress or changing situation alters needs. Lapses, relapses, or other deteriorating behaviors are treated as indicated by the initial recovery plan and may lead to a change in the intensity of treatment, reassignment to a different treatment program or setting, or criminal sanctions. If a client lapses repeatedly or relapses severely, the case manager meets with the justice and treatment partners to reassess the plan. Along with mediating between justice and treatment, the case manager functions generally—and most pointedly in these meetings—as an advocate for the client.

The client is held responsible for lapses and relapses. The consequences are more serious for someone who does not engage in treatment, for example, than for someone who works hard in treatment. However, sometimes new problems reveal unsuspected underlying issues that must be addressed, such as previously undetected mental illness, and sometimes justice and treatment have failed to use all the tools indicated by the agreed-upon plan. In such cases, plan revision or better plan adherence rather than mechanical invocation of sanctions may be appropriate.

Illinois TASC’s information systems are able to track clients throughout the criminal justice system. In many cases, a client who is rearrested remains on the case manager’s client roster. An even more critical point arises when the client leaves jail or prison, a transition that is a focus of the Sheridan program (Olson et al., 2006). Clients graduate from the TASC program when they complete their probation or parole successfully, have stable income and housing, and are engaged in recovery activities.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images News/©Getty Images

Over the 2-year period of 2007–2008, 67 percent of the 15,500 probation clients and 49 percent of the 3,100 clients in prison re-entry programs successfully completed all TASC requirements. Overall, approximately 59 percent of all Illinois TASC clients successfully complete program requirements.

CURRENT INITIATIVES AND CHALLENGES

The programs of Illinois TASC and our partners constitute the framework for a recovery-oriented system of care for substance-involved off enders. Cooperation, continuity, and comprehensiveness can always be taken further. Routine Illinois TASC activities aimed at strengthening our system include drug abuse education for criminal justice professionals, training in evidence-based practices for treatment providers, and dissemination of top-performing providers’ effective practices to other providers. We are currently implementing “recovery checkups” with clients no longer in active case management; fully electronic tracking and case files for every client; and prevention services. We are also developing a program, called Halfway Back, that allows individuals who have been released from prison and placed in community-based treatment programs, but are faltering, to enter a residential facility without being rein-carcerated.

The system must be strengthened in rural areas, where available treatment and recovery supports, including transportation and employment, are limited. To better implement evidence-based and specialized practices in these communities, there is a need for training, clinical tools, and resource management to meet the needs of small case loads over large distances. Illinois TASC benefits from committed staff in rural areas who apply techniques such as strengths-based assessments and behavioral contracting with clients (Clark, Leukefeld, and Godlaski, 1999) and intensive case management. In a pilot project involving Illinois TASC clients with mental illness and substance use disorders, intensive case management was associated with reduced legal problems and symptoms (Godley et al., 2000).

CONCLUSION

Illinois TASC works with Illinois criminal justice and substance treatment systems to coordinate the use of their respective tools and capabilities. Our guiding concept is that of a recovery-oriented system of care that combines criminal justice authority, substance treatment interventions, and case management to best effect against recidivism and for recovery throughout an offender’s criminal justice involvement. The system that is evolving from this partnership currently includes programs for offenders in pre-adjudication, sentencing, prison, and parole status. Illinois TASC’s role is to mediate between justice and treatment, assess clients and assign them to treatment programs that meet their individual needs, monitor clients and advocate for them, and evaluate and provide quality improvement services to treatment providers. An independent mediating agency can balance criminal justice and treatment goals in order to reduce recidivism and increase recovery success among substance-involved offenders.

REFERENCES

- Brewer MK. The contextual factors that foster and hinder the process of recovery for alcohol dependent women. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2006;17(3):175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Center on Evidence-Based Interventions for Crime and Addiction. Implementing Evidence-Based Drug Treatment in Criminal Justice Settings: Final Conference Report. 2007. www.tresearch.org/centers/CEICAFinalReport2006.pdf.

- Clark JJ, Leukefeld C, Godlaski T. Case management and behavioral contracting: Components of rural substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1999;17(4):293–304. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon G. Therapeutic community treatment in correctional settings: Toward a recovery-oriented integrated system(ROIS) Offender Substance Abuse Report. 2007;7(6):81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Glaze LE, Bonczar TP. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin. Washington, DC: Department of Justice; 2007. Probation and parole in the United States, 2006. NCJ Publication No. 220218. [Google Scholar]

- Godley SH, et al. Case management for dually diagnosed individuals involved in the criminal justice system. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;18(2):137–148. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Department of Corrections. Sheridan Correctional Center National Drug Prison & Reentry Therapeutic Community: Integrated Standard Operation Procedure Manual. Chicago, IL: Department of Corrections; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- James DJ, Glaze LE. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. Washington, DC: Department of Justice; 2006. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates . NCJ Publication No. 213600. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB, DeMatteo DS, Festinger DS. A sober assessment of drug courts. Federal Sentencing Reporter. 2003;16:153–157. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB, Patapis NS, DeMatteo DS. Amenability to treatment of drug offenders. Federal Probation. 2003;67:40–46. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, et al. Improving continuity of care in a public addiction treatment system with clinical case management. The American Journal on Addictions. 2005;14(5):426–440. doi: 10.1080/10550490500247099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson DE, et al. Sheridan Correctional Center Therapeutic Community: Year 2. Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority: Program Evaluation Summary. 2006;4(2):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Taxman F, Bouffard J. The importance of systems in improving offender outcomes: New frontiers in treatment integrity. Justice Research and Policy. 2000;2(2):37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE. The Natural History of Alcoholism Revisited. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- White WL, Kurtz E, Sanders M. Recovery Management. Chicago, IL: Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. Drug and Alcohol Use and Related Matters Among Arrestees, 2003. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Justice; 2004. NCJ Publication No 212900. [Google Scholar]