Abstract

We studied the effectiveness of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (OFC) treatment of bipolar depressive episode (7 weeks, study period 1 [SP1]). Study period 1 responders (mean modal daily OFC dosage, 10.8/27.8 mg) were randomized to OFC continuation treatment or olanzapine (OLZ) monotherapy starting at 10 mg (12 weeks, SP2). Seventy-three percent of the 114 patients who entered into SP2 completed the trial. The Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total score changes from baseline in SP1 (primary outcome) were significant (−20 ± 10, P < 0.001) and, during SP2, worsened for patients in the OLZ group (OFC vs OLZ, −0.4 ± 7.55 vs +8.2 ± 14.1, respectively; P < 0.001). During SP1, 69% responded and 59% remitted. During SP2, significantly more patients in the OFC group maintained response (31.3% vs 12.5%) and remission (71.4% vs 39.6%) than patients in the OLZ group. Treatment-emergent adverse events with OFC (SP1 and SP2) included increased appetite, increased weight, somnolence, anxiety, insomnia, and depressed mood. Since visit 1, the mean weight increases (in pounds) were 4.8 ± 6.8 for SP1 (P < 0.001) and 6.3 ± 10.3 (OFC) or 10.7 ± 11.3 (OLZ) for SP2; 50% (OLZ) and 33% (OFC) of the patients had a 7% or higher weight increase. For cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein levels and some hepatic enzymes, there were statistically and clinically significant changes in both study periods but no differences between the SP2 groups. Study limitations included the open-label design and exclusion of the SP1 nonresponders from SP2. These study results suggest that improvements resulting from 7 weeks of acute OFC treatment of a bipolar depressive episode are maintained in responders for an additional 12 weeks with OFC, but switching to OLZ alone may result in symptom worsening.

Keywords: bipolar depression, continuation treatment, fluoxetine, OFC, olanzapine

Compared with manic episodes, depressive episodes of bipolar disorder are more common, have a higher risk of suicide, and are of longer duration.1 Control is difficult, usually results in considerable morbidity and resource use, and may be complicated by the possible risk of switching to mania and induction of rapid cycling.2,3

Although olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (OFC)4 and quetiapine5 are currently the only Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments for acute bipolar depression (BD), current guidelines recommend either lithium or lamotrigine as first-line treatment3 or combination with selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors or bupropion.6 Olanzapine (OLZ) monotherapy has not been approved for the treatment of BD but has demonstrated efficacy in bipolar depressive episodes, albeit with a lower effect size for the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score than for OFC.7

Latinos make up 14.2%8 of the US population, and estimates of bipolar disorder (types 1 and 2) lifetime prevalence in Puerto Ricans living in the island are approximately 2%.9 Our study is the first, to our knowledge, to evaluate the effectiveness of OFC and its comparison versus OLZ in a Latino (Puerto Rican) population. A previous subanalysis in Latinos with acute mania showed that OLZ is efficacious and comparable to haloperidol and to the effectiveness observed in the white population.10

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients were treated with OFC for 7 weeks (SP1) following an open-label design, and those achieving a Clinical Global Impressions of Severity of Bipolar Depression (CGI-BP-D) score of 3 or lower plus a reduction of 50% or greater in the MADRS total score were randomized for 12 weeks to take either OLZ or continued OFC (SP2). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional review board at each site, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study Objectives

The primary objective was to assess the effectiveness of variable once-daily doses of OFC after 7 weeks, measured by the mean change from baseline in the MADRS total score. Secondary objectives included the following: For SP1, (a) treatment effectiveness measured by the mean change from baseline in the CGI-BP-D score,11 the mean change from baseline in each item of the MADRS scale, the rate of response (reduction of at least 50% in the total score of MADRS12 and a CGI-BP-D11 score < 3 at end point), and the rate of remission (an end point MADRS total score ≤12)12; (b) emergence of mania (CGI-BP-Mania score11 ≥3 or hospitalization for mania at any time) in patients with BD; (c) changes in the health-related quality of life and functional states in patients using the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12)13; and (d) safety based on spontaneously reported adverse events, changes in vital signs, changes in laboratory analytes, and incidence of treatment-emergent abnormal laboratory analytes.

For SP2, the secondary objectives included (a) differences in continuing treatment based on the proportion of patients remaining in the trial at the end point, (b) differences in maintaining control of bipolar symptoms by comparing the proportion of patients who experienced symptomatic depressive relapse (MADRS score14 ≥20 plus a CGI-BP-D score11 ≥3) or hospitalization for depression, (c) differences in emergence of mania (CGI-BP-Mania score11 ≥3 or hospitalization for mania at any time), (d) differences in the health-related quality of life and functional states in patients using the SF-12,13 and (e) differences in safety as for SP1.

Selection of Patients and Daily Starting Doses

Patients in this study met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision, Bipolar Disorder disease criteria, bipolar type 1 or 2; were outpatients; were 21 years or older; were without communication problems; had experienced hypomanic, manic, or mixed episode for 1 year or more; and had a MADRS total score of 20 or higher at visit 1. The following patients were excluded: site/Lilly personnel or their immediate families; poor responders to OLZ and/or fluoxetine; pregnant or breast-feeding; patients with current substance dependence; patients with serious or unstable nonpsychiatric illness; patients who had taken clozapine or electroconvulsive therapy within 90 days, OLZ, depot antipsychotics within 30 days, fluoxetine within 35 days or a monoamine oxidase inhibitor within 14 days before visit 1; patients who were on any other medication with primary central nervous system activity; patients who were considered at serious suicidal risk; or rapid-cycling patients. Daily starting drug dosages were 12/25 mg of OFC (range, 6/25–12/50 mg) for SP1 and the OFC final dose of SP1 (range, 6/25–12/50 mg) for SP2; the daily starting drug dosage for OLZ was 10 mg (range, 5–20 mg).

Statistical Methods

Primary Analyses

The mean changes from baseline to the last observation carried forward (LOCF) end point of the MADRS during SP1 were compared with zero change using a paired t test. During SP2, LOCF changes from baseline (V4) on the MADRS score were compared across groups using an analysis of covariance with terms for baseline score, treatment, and investigator in the model.

Secondary Analyses

Changes over time in the MADRS, the CGI-BP-D, and the CGI-BP-Mania were analyzed using a mixed models repeated measures (MMRM) approach with terms for baseline score, investigator, and visit during SP1. During SP2, changes over time in CGI-BP-D and CGI-BP-Mania were compared across treatment groups using an MMRM model with terms for baseline score (at V4), investigator, treatment, visit, and the treatment by visit interaction. Changes from baseline to LOCF end point for secondary measures were analyzed using the same methodology as for the primary analysis. Analyses of LOCF changes from baseline for safety outcomes during SP2 were repeated using V1 as baseline to assess changes over the entire course of the treatment. Categorical variables (eg, sex, ethnicity, and baseline characteristics) and outcome measures (eg, incidence of response, compliance, and treatment-emergent adverse events [TEAEs]) were summarized during SP1 and compared across groups during SP2 using Fisher exact test. For discontinuation purposes, patient noncompliance was defined as missing all doses either for 5 consecutive days or for 14 cumulative days; for analyses purposes, it was defined as not taking the medication as prescribed. Continuous patient characteristics were compared across groups who were randomized at V4 using analysis of variance with treatment and investigator in the model. Time to relapse during SP2 was compared across groups using the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and the log-rank test.

RESULTS

Demographics

Most enrolled patients (92.5%) had a diagnosis of bipolar type 1, and 34% were men. Other SP1 baseline characteristics (mean ± SD) include age of 42.4 ± 11.2 years, a MADRS total score of 32.3 ± 7.4, a CGI-BP-D score of 4.5 ± 1.0, and a CGI-BP-Mania score of 1.1 ± 0.4. No significant differences were observed in demographics at randomization for SP2 (OFC and OLZ, respectively): male sex, 42% and 32%; origin (Latino), 93% and 86%; and mean ± SD age of 44.4 ± 11.9 years and 41.6 ± 10.7 years; body mass index of 29.5 ± 5.0 and 29.8 ± 6.7; MADRS score of 32.1 ± 7.1 and 32.9 ± 7.7; CGI-BP-D score of 4.5 ± 1.0 and 4.5 ± 1.2; and CGI-BP-Mania score of 1.1 ± 0.3 and 1.2 ± 0.4.

Effectiveness Measures

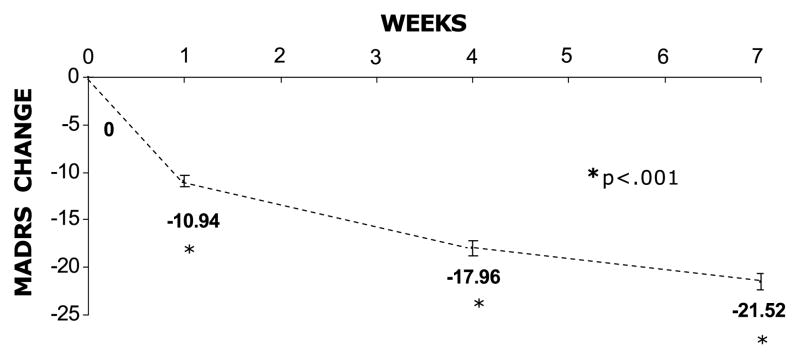

In SP1, 161 patients were enrolled and 29.2% discontinued (3.7% because of adverse events); drug compliance was 86%; the mean modal dosage of OFC was 10.8/27.8 mg/d (n = 160); the mean ± SD OFC exposure was 48 ± 18 days; and rates of mania, response, and remission were 4.3%, 69%, and 58.7%, respectively. The OFC was associated with a statistically significant mean ± SD reduction on the MADRS total score from the baseline (−20.0 ± 10.0; P < 0.001) and the CGI-BP-D (−2.5 ± 1.4; P < 0.001) to LOCF end point over 7 weeks. The initial 12:25 mg/d dosage resulted in a statistically significant reduction on the MADRS and the CGI-BP-D scores in the first treatment week (−10.94 and −1.12, respectively; P < 0.001; Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

SP1: MMRM MADRS total score change.

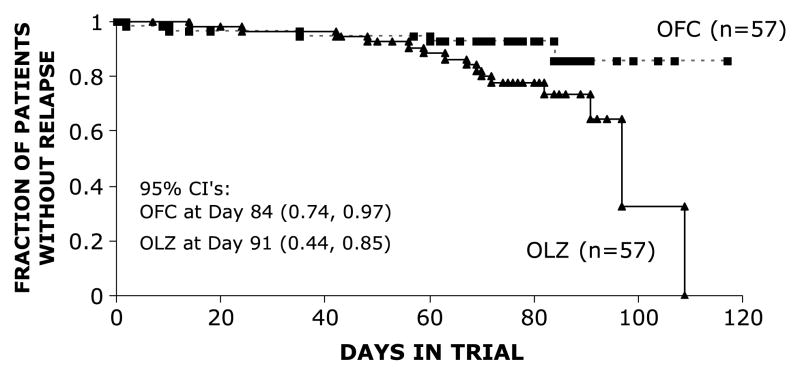

In SP2, discontinuation rates were similar between groups OLZ, 31.6% (1.8% due to adverse events), and OFC, 22.8% (5.3% due to adverse events). Mean modal daily doses were 10.3/33.6 mg (OFC, n = 55) and 10.8 mg (OLZ, n = 55). Mean ± SD drug exposure was 72 ± 26 days (OFC) and 70 ± 24 days (OLZ), and drug compliance was 77% (OFC, n = 57) and 77% (OLZ, n = 57; P value, non-significant). The MADRS change from baseline (V4) was −0.4 ± 7.55 for the OFC arm (n = 49) but worsened by + 8.2 (±14.1) in the OLZ arm (n = 48; LOCF P < 0.001). Other than for suicidal ideation, reduced appetite, and reduced sleep, there was a statistically different worsening in 7 of the 10 MADRS individual items from baseline in the OLZ versus the OFC arm. The OLZ arm had a statistically significant increase in the CGI-BP-D score (1.3; MMRM, P < 0.001). Response rates were 31.3% (OFC) and 12.5% (OLZ, P < 0.05), and remission rates were 71.4% (OFC) and 39.6% (OLZ, P < 0.01). The mania emergence rates were low in each group (OFC, 1.8%; OLZ, 0%; P value, NS). The relapse rates were 28.1% OLZ versus 10.5% OFC (P < 0.05). The median days to relapse was not estimable for the OFC arm because of the low relapse rate but was 97 days in the OLZ arm (Fig. 2, P [log-rank] = 0.0196).

FIGURE 2.

SP2: Relapse defined as a MADRS total score of 20 or higher and a CGI-S-D score of 3 or higher or hospitalization for depression (log rank, P = 0.0196).

Safety Measures

There were 16 serious adverse events (SAEs) in 6 patients during SP1: adhesions (intestinal), aggression, appendectomy, appendicitis, blood triglycerides increased, cholelithiasis, hallucination (auditory), impulse-control disorder, judgment impaired, mania, pancreatitis, platelet count decreased, positive pregnancy test result, pyrexia, suicidal ideation, viral infection, and 5 SAEs in 3 OFC patients (asthenia, decreased interest, depressed mood, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt), and 1 SAE in an OLZ patient (pregnancy) during SP2. There were no deaths. The TEAEs reported in 10% or more of the patients during SP1 (N = 161) were increased appetite (28%), increased weight (18.6%), somnolence (16.1%), anxiety (14.9%), tremor (12.4%), sedation (11.8%), and dry mouth (11.2%). During SP2 (V4 as baseline), there was a similar (P = 0.417) incidence of patients with at least 1 TEAE among the groups: 37/57 (64.9%, OFC) and 42/57 (73.7%, OLZ). Depressed mood was the only significantly different TEAE in SP2 (19.3% OLZ vs 5.3% OFC, P = 0.043). There was a statistically significant increase during SP1 in the mean body weight (4.8 lb; P < 0.001). Differences in mean ± SD weight change were not statistically significant between OFC and OLZ arms during SP2 using visit 1 as baseline (6.3 ± 10.3 lb vs 10.7 ± 11.3 lb, respectively). From V1 to any post-V4 visit, there was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of patients with a clinically significant increase (≥7%) in body weight (18/54 [33.3%] for OFC versus 27/54 [50.0%] for OLZ, P = 0.118). When measured from the point of randomization (V4) to any post-V4 visit, there was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of patients with a clinically significant increase (≥7%) in body weight (OFC, 3/53 [5.7%]; OLZ, 6/54 [11.1%]; P = 0.489). We observed several clinically relevant treatment-emergent abnormal laboratory values (defined as values exceeding laboratory reference ranges after initiation of treatment among patients who were within normal limits before treatment) after baseline (V1) in SP1 with significant increases (mean ± SD) for cholesterol (14.4 ± 36.6 mg/dL), low-density lipoprotein (9.9 ± 31.6 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (2.7 ± 7.7 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (5.2 ± 12.9 U/L), and alkaline phosphatase levels (5.5 ± 12.7 U/L). The differences in laboratory values between OLZ and OFC during the SP2 were significant for aspartate aminotransferase increase (5/44 vs 0/47, respectively; P = 0.023) and for alkaline phosphatase (OLZ vs OFC, mean ± SD, 3.2 ± 11.67 vs 3.3 ± 14.55, respectively; P = 0.009). There were no clinically significant changes in vital signs, but some statistically significant within-group increases were observed in standing pulse and standing diastolic blood pressure using V1 as baseline. Additional study details are reported elsewhere.15

Health Outcomes

During SP1, there was a statistically significant mean ± SD improvement from baseline on the SF-12 Mental and Physical Component scores for OFC-treated patients (12.7 ± 11.6, P < 0.001, and 3.9 ± 10.9, P = 0.001, respectively). During SP2, compared with the OLZ arm (n = 41), the OFC arm (n = 43) showed significantly less worsening on the SF-12 total score (−1.5 versus −8.7, P = 0.021), and mental (−0.8 vs −6.7, P = 0.039) and physical components (−0.7 vs −2.1; P value, NS).

DISCUSSION

During SP1, a mean change of −20.0 ± 10.0 in the MADRS total score (OFC treatment at a starting once-daily dose of 12/25 mg; mean modal daily dosage, 10.8/27.8) was observed, with 71% completing the study period and a few patients experiencing an emergence of mania. The mean weight increase (SP1) was 4.8 ± 6.8 lb, and 17% had a 7% or higher weight increase. Our data also suggests that OFC treatment for an additional 12 weeks may be more effective than switching to OLZ monotherapy in maintaining response in patients with BD with similar tolerability.

These results in Latinos supplement evidence from 2 white population studies. In one, 86 patients were randomized to OFC for 8 weeks starting at 6/25 (mean modal dose was 7.4/39.3 mg/d).7 Results included an MADRS mean change of −18.5; response and remission rates of 56% and 49%, respectively; a mania emergence of 6.4%; 64% completing the study; a mean weight gain of 7.09 ± 8.20 lb; and 19.5% having a 7% or higher weight gain. The other study used OFC (n = 205; mean modal dosage, 10.7/38.3 mg/d; 25% of the patients on the 12/25 mg/d dosage) and lamotrigine (n = 205)12 for 7 weeks. Results included an MADRS mean change of −14.91; response and remission rates of approximately 69% and 56%, respectively; a rate of affective switch of 4%; 67% completing the study; a mean weight gain of 3.1 ± 3.4 kg; and 23% of the patients having a 7% or higher weight gain. In the 25-week study extension phase,16 the completion rate was 33%, 64% responded, 56% remitted, and the incidence of mania emergence was 5%. The MADRS and CGI-S improvements were maintained over the extension phase.

Acknowledging differences in study characteristics, there were similar MADRS reductions, response and remission rates, mania emergence rates, and study completion rates. However, numerically less weight increase in our Puerto Rican study contrasts a previous analysis where Latinos had significantly higher weight increases with OLZ than in whites.10 Reasons for the worsening MADRS in SP2 in those switched from OFC could (1) suggest an advantage of OFC over OLZ in maintenance of response, (2) indicate a worsening with OLZ, (3) be specific to the Latinos studied, or (4) be a biased assessment due to the open-label design.

Our study outcomes differ from the recent effectiveness study (Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder)17 in which antidepressants plus mood stabilizers neither improved the depressive symptoms nor increased the risk of a switch to mania in 366 patients with BD. This was likely because of options for psychotherapy and different drugs and objectives. Still, the antidepressant plus mood stabilizer combination in BD maintenance has shown encouraging results,14,18,19 and our study clearly supports OFC treatment. In addition, we found that the continuation treatment with this combination is more effective than switching to OLZ monotherapy, and concerns about induction of mania or rapid cycling are not warranted if fluoxetine is combined with OLZ. In light of currently available data, there is strong support for future large clinical studies to elucidate the role of antidepressants in the treatment of a bipolar depressive episode.19

There were several limitations to our study. First, the open-label design may have led to investigator and patient expectation effects and biases. Second, all SP1 nonresponders were excluded from SP2, which produced an enriched sample that would not generalize to the population of all patients with BD but to those who would meet the response criteria to OFC treatment. In addition, the exclusion of nonresponders from SP2 prevented an investigation of patients who might have reached the response criteria with longer than 7 weeks of exposure to OFC. Third, psychotic and rapid-cycling patients were excluded. Fourth, the Young Mania Rating Scale was not collected; thus, remission was defined as a single pole assessment measure. Nevertheless, only 1 patient demonstrated an emergence of mania defined as a CGI-S-Mania score of 3 or more or hospitalization for mania during SP2, suggesting that many patients were in mania remission. Lastly, the unique characteristics of care/support in Puerto Rico may limit the generalizability of results in other regions.

This study suggests that acute treatment gains and safety in Puerto Rican patients with BD treated with OFC are maintained for up to 19 weeks. Patients switched to OLZ after 7 weeks demonstrated significantly worse outcomes on depressed mood, relapse rates, times to relapse, and SF-12 scores. Future double-blind, controlled, long-term studies with OFC treatment of BD in Latinos or switching from OFC to OLZ in other populations are needed to confirm these findings.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the investigators, Ellen Syphers, Wei Zhou, and the Lilly Puerto Rico Study Team.

Financial support was provided by Lilly USA, LLC.

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00191399.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE INFORMATION

Drs Tamayo and Sutton were employees of Lilly USA, LLC, during the study. Dr Tamayo is currently a speaker for Lilly, Biocodex-EuroEtika, Pfizer, and Wyeth. Mr Mattei and Mr Jamal are employees of Lilly USA, LLC. Dr Zarate has no conflict of interest to report and receives no funding from industry. Dr Diaz has received grants from Lilly and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), has been a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) and Wyeth, and is a speaker for Lilly, GSK, Pfizer, Janssen, Wyeth, Forest, and BMS. Dr Vieta has been a consultant, has received grants from, or has been a speaker for the following companies: Almirall, AstraZeneca, Bial, BMS, Forest Research Institute, Lilly, GSK, Janssen-Cilag, Jazz, Lundbeck, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Qualigen, Sanofi Aventis, Servier, Shering-Plough, UCB, Wyeth, the Spanish Ministry of Health, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, CIBERSAM, and the Stanley Medical Research Institute. Dr Fumero has been a speaker for Lilly, BMS, Forest, Pfizer, Cyberonics, Wyeth, and Janssen and has received grants from Novartis and Lilly. Dr Tohen was an employee of Eli Lilly and Company and is currently a consultant or has received honoraria from Johnson and Johnson, Lilly, AstraZeneca, GSK, and BMS. His spouse is currently with Lilly USA, LLC, and an Eli Lilly and Company stockholder.

References

- 1.Thase ME. Bipolar depression: diagnostic and treatment considerations. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18:1213–1230. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cousins DA, Young AH. The armamentarium of treatments for bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006:1–21. doi: 10.1017/S1461145706007413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirschfeld RMA. American Psychiatric Association; 2006. [Accessed June 22, 2007]. Guideline watch: practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. Available at: http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/treatg/pg/prac_guide.cfm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Symbyax [package insert] Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.AstraZeneca. Seroquel [package insert] Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan C, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2007. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:721–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1079–1088. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Census Bureau. The American Community—Hispanics: 2004. US Census Bureau; 2007. [Accessed on April 16, 2007]. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/GRTTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-_box_head_nbr=R0504&-ds_name=ACS_2005_EST_G00_&-format=US-30. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canino G, Bird H, Rubio-Stipec M, et al. The epidemiology of mental disorders in the adult population of Puerto Rico. P R Health Sci J. 1997;16:117–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamayo JM, Mazzotti G, Tohen M, et al. Outcomes for Latin American versus white patients suffering from acute mania in a randomized, double-blind trial comparing olanzapine and haloperidol. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:126–134. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318033bd4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spearing MK, Post RM, Leverich GS, et al. Modification of the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scale for use in bipolar illness (BP): the CGI-BP. Psychiatry Res. 1997;73:159–171. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown EB, McElroy SL, Keck PE, Jr, et al. A 7-week, randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination versus lamotrigine in the treatment of bipolar I depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1025–1033. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawley CJ, Gale TM, Sivakumaran T. Defining remission by cut off score on the MADRS: selecting the optimal value. J Affect Disord. 2002;72:177–184. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00451-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Study F1D-SU-HGMA: Bipolar Depression Assessment Study on Treatment Response (BiDAS-TR) [Accessed on February 27, 2009];2007 Available at: http://pdf.clinicalstudyresults.org/documents/company-study_3066_0.pdf.

- 16.Brown E, Dunner D, Adams DH, et al. Olanzapine/fluoxetine combination versus lamotrigine in the long term treatment of bipolar I depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;(suppl 59):25S. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1711–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altshuler LL, Suppes T, Black DO, et al. Lower switch rate in depressed patients with bipolar II than bipolar I disorder treated adjunctively with second-generation antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:313–315. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salvi V, Fagiolini A, Swartz HA, et al. The use of antidepressants in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1307–1318. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]