Abstract

Anionic lipids influence the ability of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor to gate open in response to neurotransmitter binding, but the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. We show here that anionic lipids with relatively small headgroups, and thus the greatest ability to influence lipid packing/bilayer physical properties, are the most effective at stabilizing an agonist-activatable receptor. The differing abilities of anionic lipids to stabilize an activatable receptor stem from differing abilities to preferentially favor resting over both uncoupled and desensitized conformations. Anionic lipids thus modulate multiple acetylcholine receptor conformational equilibria. Our data suggest that both lipids and membrane physical properties act as classic allosteric modulators influencing function by interacting with and thus preferentially stabilizing different native acetylcholine receptor conformational states.

Introduction

Cys loop receptors are a superfamily of membrane proteins that mediate synaptic transmission in both the central and peripheral nervous systems (1). They respond to the binding of the neurotransmitter by transiently opening an ion channel across the cell membrane. The resultant influx of ions into the cell alters the membrane potential leading to either the generation or the inhibition of an action potential. Any factor that influences the duration or magnitude of the neurotransmitter-induced response will alter the efficiency of synaptic transmission with important biological and potentially pathological consequences (2, 3).

Lipids are potent modulators of Cys loop receptor function (4). The lipid sensitivity of one Cys loop receptor, the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR)3 from Torpedo, has been particularly well studied. The ability of the nAChR to undergo allosteric transitions, and thus conduct cations across the membrane in response to agonist binding, is highly dependent upon the lipid composition of the membrane in which it is embedded (5–12). In native Torpedo membranes, a complex mixture of lipids works synergistically to stabilize predominantly the agonist-activatable resting nAChR (9). In contrast, the nAChR reconstituted into phosphatidylcholine membranes (PC-nAChR) does not undergo agonist-induced allosteric transitions unless neutral and/or anionic lipids are present (5–13).

PC-nAChR is unresponsive to agonist because it adopts an uncoupled conformation where allosteric communication between the agonist-binding and transmembrane pore domains is lost, even though both domains adopt structures suggestive of the activatable resting state (14). Lipids are thought to influence coupling by interacting with the highly lipid-exposed M4 transmembrane α-helix. M4 extends beyond the lipid bilayer toward the eponymous Cys loop, which is central for coupling agonist binding to channel gating (15, 16). M4 may act as a “lipid sensor” relaying membrane properties to the coupling interface between the agonist binding and transmembrane pore domains. By interacting preferentially with M4 in the coupled resting conformation, lipids may stabilize the resting state (14).

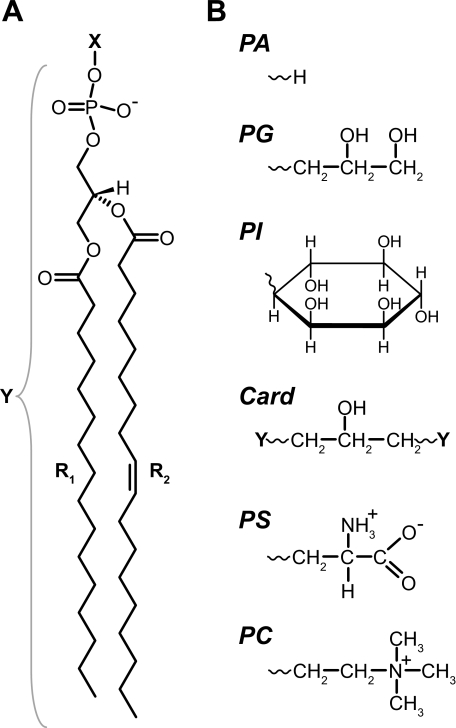

Most studies suggest that the nAChR requires both anionic and neutral lipids in a PC membrane to adopt an agonist-activatable conformation (6, 11, 12). Of the many natural anionic lipids, phosphatidic acid (PA) is particularly effective. High levels of PA in a PC membrane are sufficient to stabilize an agonist-activatable nAChR (9, 17). In contrast, the nAChR in a PC membrane containing the anionic lipid, phosphatidylserine (PS), is not responsive to agonist unless cholesterol (Chol) is present (18). The strikingly different efficacies of PA and PS suggest that PA imparts a unique chemical and/or physical property onto the reconstituted membranes that is required to stabilize the resting conformation. One obvious chemical difference is the charge distribution within the two lipid headgroups (Fig. 1), which could lead to essential interactions between PA and polar side chains in the resting conformation. Alternatively, the PA headgroup is much smaller than the headgroup of PS and will have a larger influence on lipid packing/bilayer physical properties (19). Membrane physical properties could influence transmembrane helix:helix associations to favor the resting nAChR.

FIGURE 1.

Chemical structures of anionic phospholipids. A, phospholipid molecules studied here contain palmitoyl (R1) and oleoyl (R2) acyl chains attached to a phosphoglycerol backbone. The headgroup (X) connects to the phosphate moiety. For PI, both R1 and R2 are oleoyl chains. B, structures of various headgroups (X). Cardiolipin (Card) is composed of two phospholipid moieties (Y in A) linked through a single glycerol moiety.

The initial goal of this work was to probe the mechanism(s) by which PC/PA membranes stabilize an agonist-activatable nAChR. We examined a variety of reconstituted PC/anionic lipid membranes and found that anionic lipids with relatively small headgroup cross-sectional areas, and thus the greatest ability to influence lipid packing/bilayer physical properties, are the most effective at stabilizing an agonist-activatable resting conformation. This suggests that membrane physical properties play a role in stabilizing the resting nAChR.

More importantly, we also found that the differing abilities of PC/anionic lipid membranes to stabilize an activatable nAChR stem from differing abilities to preferentially stabilize resting over both uncoupled and desensitized conformations. In other words, anionic lipids modulate multiple nAChR conformational equilibria. Our findings suggest that both lipids and membrane physical properties act as classic allosteric modulators influencing nAChR function by preferentially interacting with and thus stabilizing native conformational states.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Frozen Torpedo californica electroplax tissue was obtained from Aquatic Research Consultants (San Pedro, CA). 1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol (PG), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine (PS), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoinositol (PI), and cardiolipin (tetraoleoyl) were from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). Cholesterol, ethidium bromide (EtBr), and carbamylcholine chloride (Carb) were from Sigma.

nAChR Purification and Reconstitution

The nAChR was affinity-purified on a bromoacetylcholine bromide-derivatized Affi-Gel 102 column (Bio-Rad) as described elsewhere (17). The column-bound nAChR was washed extensively with dialysis buffer (100 mm NaCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 0.02% w/v NaN3, pH 7.8) containing 1% cholate and supplemented with 3.2 mm of the desired lipid. The nAChR was then eluted from the column with a 0.13 mm lipid solution in 250 mm NaCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 0.02% NaN3, 5 mm phosphate, pH 7.8, with 0.5% cholate and 10 mm Carb. After elution from the column, the nAChR was dialyzed five times against 2 liters of dialysis buffer with buffer change approximately once every 12 h. The final lipid composition of each membrane was assessed by thin layer chromatography as described below. The reconstituted membranes have lipid:protein ratios in the 150–300 mol/mol range, as estimated by Fourier transform infrared (20) and enzymatic assays (phospholipid C/choline assay, Wako Chemicals).

Thin Layer Chromatography

TLCs were performed using high performance silica gel plates (60 Å, 4.5-μm particle size; Whatman) as described (14), but with the following modifications. A dual solvent system was used for development to better resolve individual lipid species. Plates were initially developed halfway in a chloroform/methanol/formic acid/H2O (50:37.5:3.5:2, v/v) solvent system. After air drying, the plates were developed further in a benzene/2-propanol/ethyl acetate/formic acid (72.5:3.5:22:2) solvent system. The TLC analysis shows that each of the reconstitutions exhibited the expected PC:anionic lipid ratio, although PC/PA-nAChR contains small amounts of diacylglycerol (see supplemental Fig. S5 and supplemental discussion for details).

Infrared Spectroscopy

All infrared spectra were recorded on either an FTS-575c or an FTS-40 spectrometer (Varian, Randolph, MA) as described previously (17). Both spectrometers were equipped with a DTGS detector. For the analysis of protein secondary structure, the extent of peptide hydrogen/deuterium exchange, and lipid thermotropic phase behavior, each nAChR sample was first incubated at 4 °C in 2H2O phosphate buffer for precisely 72 h to exchange peptide N-1H for N-2H. The samples were then stored at −80 °C. Prior to infrared analysis, samples were individually thawed, centrifuged, resuspended in 30 μl of 2H2O phosphate buffer, and subjected to five freeze-thaw vortex cycles. All infrared spectra were recorded in Torpedo Ringer buffer (TRB: 5 mm Tris, 250 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, and 3 mm CaCl2, pH 7.0). Where necessary, trace water vapor absorptions were subtracted as described elsewhere (21). All spectral deconvolution was performed using GRAMS/AI version 7.01 software (Galactic, Salem, NH).

The data acquisition protocols for assessing the thermotropic phase behavior of the membranes have been described previously (17). Briefly, 128 scans at 2 cm−1 resolution were acquired at 1° intervals as the sample was cooled from 35 to −10 °C. Note that all of the 2H2O buffers were prepared by drying the corresponding H2O buffers, pH 7.0, and then rehydrating them with the appropriate volume of 2H2O. The pD values were then verified with litmus paper.

Infrared difference spectra were recorded at 22.5 °C using the attenuated total reflectance technique as described in detail elsewhere (22, 23). Briefly, two spectra were recorded while flowing TRB past nAChR film that was deposited on the surface of a germanium internal reflection element. The flowing buffer was switched to an identical buffer containing 50 μm Carb, and after 1 min a spectrum was recorded of the Carb-bound state. The nAChR film was then washed with TRB for 20 min to remove nAChR-bound Carb, and the data acquisition protocol was repeated. All spectra were recorded at 8 cm−1 resolution, signal-averaging 512 scans per spectrum, which takes ∼7–8 min per spectrum. Each presented difference spectrum is the average of more than 40 individual difference spectra recorded from several different reconstituted nAChR films. The difference spectra were base-line corrected between 1800 and 1000 cm−1 and were interpolated to an effective resolution of 4 cm−1.

Ethidium Fluorescence Measurements

All fluorescence experiments were performed on a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer equipped with the Cary Eclipse version 1.1 software package (Varian). The data in Figs. 4 and 5 were acquired by monitoring the fluorescence emission intensity at 590 nm as a function of time (2.0-s sampling time) while ethidium bromide was continuously excited at 500 nm (excitation and emission slits are described in the associated figure legends). The data in Fig. 6 were acquired with 530 nm excitation to enhance the emission intensity arising from nAChR-bound ethidium and reduce the intensity of the signal arising from ethidium in solution.

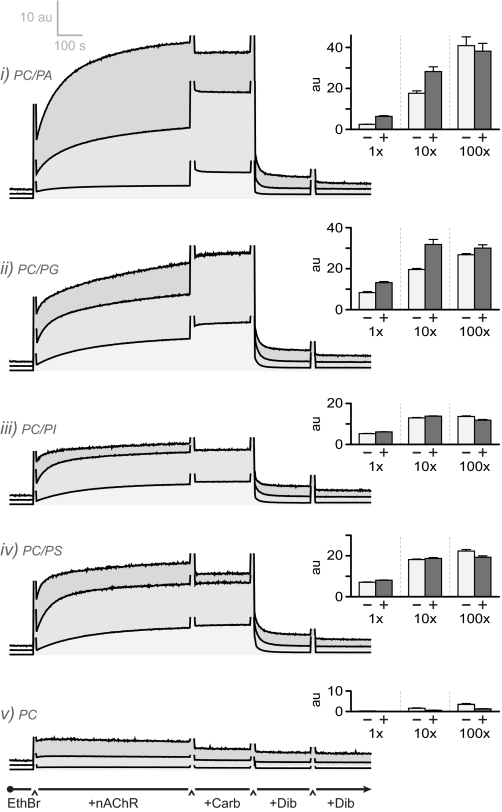

FIGURE 4.

Anionic lipids influence conformational transitions involving the nAChR pore. Conformational transitions of the nAChR pore were probed by monitoring the fluorescence of dibucaine-displaceable ethidium binding. The fluorescence emission of ethidium at 590 nm was monitored in the presence of the nAChR reconstituted into the following: trace i, 3:2 PC/PA; trace ii, 3:2 PC/PG; trace iii, 3:2 PC/PI; trace iv, 3:2 PC/PS; and trace v, PC membranes, using 20 nm excitation and emission slit widths. A, at the indicated times, ∼50 nm nAChR, 500 μm Carb, and 500 μm dibucaine were added to a 0.3 μm ethidium solution. The light gray fluorescence traces were recorded using nAChR preincubated with a large excess of α-bungarotoxin (α-Btx; final concentration = 1.0 μm). The fluorescence traces in the presence and absence of α-bungarotoxin are offset slightly to improve clarity. The sharp spikes in each fluorescence emission trace reflect the scattering of light upon insertion of the pipette into the cuvette. EthBr, ethidium bromide; Dib, dibucaine. B, dibucaine-displaceable ethidium fluorescence emission intensity at 590 nm in the presence (+) or absence (−) of Carb. Error bars are the mean ± S.E. for n = 6 experiments, three measurements each from two different reconstitutions at the indicated lipid composition. a.u., absorbance units. C, schematic for the ethidium (Eth) fluorescence measurements. Ethidium fluoresces weakly in solution (left and right) but with greater intensity when bound to the desensitized nAChR pore (middle).

FIGURE 5.

Agonist-activatable PC/PA-nAChR undergoes a rapid transient Carb-induced transition leading to increased accessibility to the ion channel pore. The fluorescence emission of ethidium at 590 nm was monitored with PC/PA-nAChR, using 20 nm excitation and emission slit widths. Trace i, at the indicated times, ∼50 nm nAChR, 500 μm Carb, and 500 μm dibucaine (Dib) were added to a 0.3 μm ethidium solution. Trace ii, nAChR was preincubated with 500 μm Carb for 30 min. At the indicated time, ∼50 nm nAChR + Carb were added to a 0.3 μm ethidium solution. Trace iii, at the indicated time, ∼50 nm nAChR was added to a solution containing both 0.3 μm ethidium and 500 μm Carb. EthBr, ethidium bromide; a.u., absorbance units.

FIGURE 6.

Ethidium binding to the nAChR provides a measure of the relative proportions of resting, desensitized, and uncoupled conformations. The fluorescence emission of ethidium at 590 nm was monitored in the presence of the nAChR reconstituted into the following: trace i, 3:2 PC/PA; trace ii, 3:2 PC/PG; trace iii, 3:2 PC/PI; trace iv, 3:2 PC/PS; and trace v, PC membranes. At the indicated times, ∼50 nm nAChR, 500 μm Carb, and two times 500 μm dibucaine (Dib) were added to ethidium at either 1× KD (0.3 μm; lowest trace), 10× KD (3.0 μm; middle trace), or 100× KD (30 μm; top trace). The fluorescence traces are offset and shaded to improve clarity. Inset, dibucaine-displaceable ethidium fluorescence emission intensity at 590 nm in the presence (+) or absence (−) of Carb. Error bars are the mean ± S.E. for n = 6 experiments; three measurements are each from two different reconstitutions at the indicated lipid compositions except for trace iii, which is n = 3 from one reconstitution. These traces were recorded with 5 nm excitation and 20 nm emission slit widths to allow comparison of the fluorescence intensities at all three ethidium concentrations. A 530 nm excitation wavelength maximizes the fluorescence intensity arising from nAChR-bound versus solution ethidium (see under “Experimental Procedures”). EthBr, ethidium bromide; a.u., absorbance units.

For each experiment in Fig. 4, 1.8 ml of 0.3 μm ethidium bromide in TRB was equilibrated at 22.5 °C inside the spectrophotometer. At the indicated times, 30 μg of nAChR suspended in 200 μl of TRB was added, followed by 10 μl of 100 mm carbamylcholine and then 10 μl of 100 mm dibucaine (i.e. ∼500 μm final concentration for both ligands). For the experiments in Fig. 5, the nAChR was either preincubated for 30 min with 5 mm Carb in 200 μl of TRB (Fig. 5, trace ii, final Carb concentration ∼500 μm) or added directly to a TRB solution containing both 0.3 μm ethidium and 555 μm Carb (Fig. 5, trace iii, final Carb concentration also ∼500 μm).

In the variable ethidium bromide concentration experiments (i.e. Fig. 6), 30 μg of nAChR was added to either a 0.3 μm (1× KD), 3.0 μm (10× KD), or 30.0 μm (100× KD) ethidium bromide/TRB solution. As above, both Carb and dibucaine were added at the indicated times. Due to higher concentrations of ethidium (i.e. 30 μm), a greater concentration of dibucaine was necessary for competitive displacement of ethidium, and a second 10-μl addition of 100 mm dibucaine was included in these experiments (i.e. final dibucaine concentration ∼1 mm).

RESULTS

Reconstitution of nAChR into PC/Anionic Lipid Membranes

To test if PA is unique among anionic lipids in its ability to stabilize an agonist-activatable nAChR, the structural and functional properties of the nAChR were examined in a broader range of PC/anionic lipid mixtures. We initially focused on PC membranes containing the anionic lipid, phosphatidylglycerol (PG), because the cross-sectional area of the PG headgroup and its effects on bilayer physical properties are more similar to that of PA than to that of PC or other anionic lipids (Fig. 1) (24, 25). Conversely, the anionic lipids phosphatidylinositol (PI) and cardiolipin have larger headgroups. If the anionic lipid headgroup cross-sectional area, and thus ability to influence the physical properties of a PC bilayer, contributes to the efficacy of PA, then mixtures of PC and PG should be more effective than mixtures of PC and either PI or cardiolipin at stabilizing an agonist-activatable nAChR.

Effects of Anionic Lipids on nAChR Structure and Peptide Hydrogen Exchange

Infrared spectroscopy has shown that the lipid composition of a reconstituted membrane does not affect the overall secondary structure of the nAChR, but it does influence nAChR peptide hydrogen exchange kinetics (26). Lipid environments that stabilize an allosterically responsive nAChR typically slow peptide hydrogen exchange suggesting that the resting/coupled conformation has a less solvent-exposed tertiary/quaternary structure than the lipid-dependent uncoupled nAChR (14, 27).

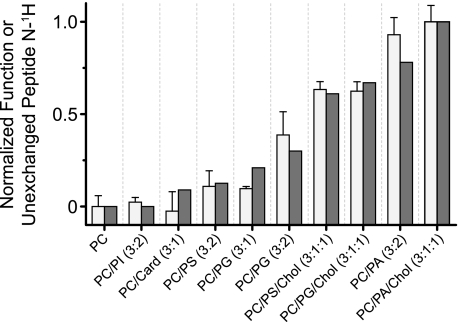

The effects of PG, PI, and cardiolipin on nAChR secondary structure and peptide hydrogen exchange were examined by recording infrared spectra of each reconstituted membrane after 72 h of exposure to 2H2O. Representative deconvolved amide I/I′ bands show that the nAChR exhibits the same mixed α-helix/β-sheet secondary structure in PC membranes with or without PG, PI, or cardiolipin (supplemental Figs. S1A and S2A). Reconstituted PG-containing membranes, however, exhibit a slightly increased intensity because of protiated versus deuterated α-helices, suggesting a reduced level of nAChR peptide hydrogen/deuterium exchange in the presence of PG. The residual amide II band intensity, which is directly proportional to the number of peptide hydrogens that remain in the protiated form, confirms that the inclusion of PG, but not PI or cardiolipin, in a reconstituted PC membrane reduces the level of peptide hydrogen/deuterium exchange. Addition of Chol to the PG-containing bilayers further slows the exchange kinetics (Fig. 2 and supplemental Fig. S1B).

FIGURE 2.

Ability of the nAChR to undergo agonist-induced allosteric transitions is correlated with reduced nAChR solvent accessibility. Solvent accessibility was assessed from the extent of nAChR peptide hydrogen/deuterium exchange in each membrane environment (white bars), as measured from the residual amide II band in spectra recorded after 72 h in 2H2O at 4 °C (supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). The relative abilities of the nAChR to undergo agonist-induced resting-to-desensitized transitions was determined from the relative intensities of the conformationally sensitive difference band centered at 1655 cm−1 (gray bars) observed in Carb difference spectra recorded from each reconstituted membrane (Fig. 3). Both nAChR activity/function and the extent of unexchanged hydrogens were normalized to the values obtained with PC-nAChR (0) and PC/PA/Chol-nAChR (1.0). For PC-nAChR, ∼20% of the peptide hydrogens are resistant to exchange after 72 h in 2H2O at 4 °C. For the PC/PA/Chol-nAChR, ∼40% of the peptide hydrogens are resistant to peptide hydrogen/deuterium exchange. The error bars for the extent of hydrogen/deuterium exchange are the mean ± S.E. for n = 2–5 measurements.

As noted, previous studies have shown an inverse correlation between the levels of nAChR peptide hydrogen exchange in a given membrane environment and the ability of the nAChR in that environment to undergo allosteric transitions (14, 27). Based on the levels of peptide hydrogen/deuterium exchange (Fig. 2), we predict the relative abilities of the PC/anionic lipid membranes for stabilizing the agonist-activatable resting state to be 3:1:1 PC/PG/Chol > 3:2 PC/PG > 3:1 PC/PG > 3:2 PC/PI ≅ 3:1 PC/cardiolipin. These predictions are borne out by direct measurements of nAChR function (see below and Fig. 2).

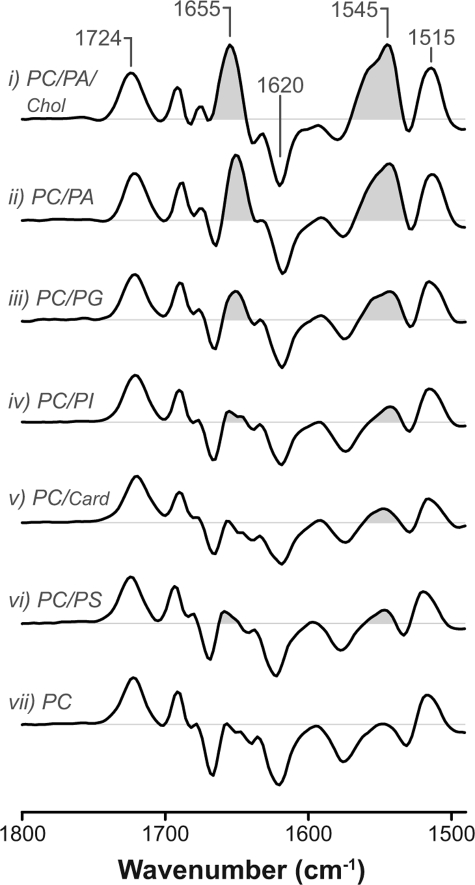

Effects of Anionic Lipids on nAChR Allosteric Transitions

Infrared difference spectroscopy probes directly agonist-induced allosteric transitions (22, 28). Carb difference spectra recorded from each of the PC/PG, PC/PI, and PC/cardiolipin membranes exhibits vibrations due to both nAChR-bound Carb (1724 cm−1) and the formation of cation-aromatic interactions between Carb and putative binding site tryptophan and tyrosine residues (1620 and 1516 cm−1, respectively) (Fig. 3 and supplemental Fig. S1) (23, 29). Carb binds to the nAChR in each of the different PC/anionic lipid membranes and does so with a similar pattern of recognition.

FIGURE 3.

Anionic lipids influence the ability of the nAChR to undergo Carb-induced structural transitions from the resting to the desensitized state. Infrared difference spectra were recorded from the nAChR in the following: trace i, 3:1:1 PC/PA/Chol; trace ii, 3:2 PC/PA; trace iii, 3:2 PC/PG; trace iv, 3:2 PC/PI; trace v, 3:1 PC/cardiolipin; trace vi, 3:2 PC/PS; and trace vii, PC membranes. The vibration near 1724 cm−1 is due to nAChR-bound Carb. Vibrations near 1620 and 1515 cm−1 reflect the formation of Carb-aromatic residue interactions in the binding site. The amide I (1655 cm−1) and II (1545 cm−1) vibrations reflect changes in the polypeptide backbone upon Carb-induced conformational change (shaded). Increasing intensity of the amide I and II difference bands correlates with an increasing proportion of nAChRs stabilized in a coupled resting conformation that undergoes desensitization. Traces i, ii, vi, and vii are from Refs. 17, 18.

Carb difference spectra recorded from the nAChR in all PG-containing lipid membranes also exhibit moderate positive amide I and amide II band intensities near 1655 and 1545 cm−1, respectively (Fig. 3, trace iii, and supplemental Fig. S1C). These vibrations, which are markers of the resting-to-desensitized structural change, show that the inclusion of PG in a PC membrane is sufficient to stabilize a small proportion of agonist-activatable resting nAChRs, even in the absence of Chol. Consistent with the hydrogen exchange data, the inclusion of Chol makes a PC/PG membrane even more effective at stabilizing a resting nAChR (Fig. 2).

In contrast, Carb difference spectra recorded from both PC/PI-nAChR and PC/cardiolipin-nAChR (Fig. 3, traces iv and v) essentially lack positive intensity near 1655 and 1545 cm−1, suggesting that the nAChR in both environments is stabilized predominantly in a conformation that does not undergo the resting-to-desensitized transition. It appears that PC/PI-nAChR and PC/cardiolipin-nAChR adopt predominantly the uncoupled conformation.

The infrared data show that membranes composed of PC with the anionic lipids PA or PG are more effective at stabilizing an agonist-activatable resting nAChR than PC membranes containing PS, PI, or cardiolipin. An additional physical or chemical property imparted onto the reconstituted membranes by PA and, to a lesser extent, PG, must play a role in modulating nAChR conformational equilibria.

Agonist-activatable PC/PA-nAChR Undergoes Rapid Allosteric Transitions

We examined further the abilities of PC/anionic lipid membranes to stabilize an agonist-activatable nAChR using the conformationally sensitive probe, ethidium bromide. Ethidium binds with high affinity to a hydrophobic site within the ion channel pore of the desensitized (KD ≅ 0.3 μm), but not the resting (KD ≅ 1 mm) nAChR (30). Relative to aqueous ethidium, nAChR-bound ethidium exhibits a greater fluorescence emission intensity, and its emission maximum shifts from 605 (aqueous solution) to 590 nm (nAChR-bound).

Addition of PC/PA-nAChR to a 0.3 μm aqueous solution of ethidium leads to an increase in dibucaine-displaceable fluorescence emission intensity (Fig. 4, trace i). At this concentration, ethidium binds to ∼50% of the pre-existing desensitized receptors but not appreciably to the resting state. Also, 0.3 μm concentrations of ethidium are not sufficient to shift a large proportion of nAChRs from the resting to the desensitized conformation (the equilibrium dissociation constant in the absence of Carb is in the 7–11 μm range) (30). The dibucaine-displaceable fluorescence observed at 0.3 μm ethidium in the absence of Carb thus represents primarily ethidium binding to pre-existing desensitized nAChRs (see also below).

Subsequent addition of 500 μm Carb leads to a substantial further increase in dibucaine-displaceable fluorescence showing that Carb binding allosterically shifts the population of resting nAChRs into the desensitized conformation. In contrast, there are essentially no changes in the fluorescence emission intensity upon the addition of PC-nAChR to aqueous ethidium, even after the addition of 500 μm Carb (Fig. 4, trace v). Consistent with the infrared difference measurements, the fluorescence data show that a substantial proportion of PC/PA-nAChR adopts a resting conformation that undergoes agonist-induced desensitization, whereas PC-nAChR is stabilized predominantly in the nonresponsive low ethidium affinity uncoupled conformation (14).

Note that the increase in fluorescence observed upon mixing PC/PA-nAChR with ethidium in the absence of Carb is slow and occurs on the seconds to minutes time scale (Figs. 4 and 5, trace i at time = 100 s). A similar slow increase in fluorescence is also observed upon mixing ethidium with PC/PA-nAChR that has been desensitized by pre-equilibration with 500 μm Carb (Fig. 5, trace ii). The slow increase in fluorescence is thus due primarily to slow binding of ethidium to the ion channel pore of the desensitized nAChR.

In contrast, the increase in fluorescence observed upon addition of Carb to PC/PA-nAChR pre-equilibrated with ethidium (Figs. 4 and 5, trace i at time = 750 s) occurs instantaneously on the seconds to minutes time scale of these experiments. Rapid binding could reflect either increased availability of ethidium to the nAChR because of prior ethidium “equilibration” with the PC/PA-nAChR vesicles or a transient Carb-induced change in nAChR conformation that dramatically increases the rate of ethidium binding. Significantly, the same rapid increase in fluorescence is also observed upon mixing PC/PA-nAChR with a solution containing both ethidium and Carb (Fig. 5, trace iii). The rapid Carb-induced increase in ethidium binding is thus due to a Carb-induced change in nAChR conformation leading to transient increased ethidium accessibility to the ion channel site. Given that ethidium is an open channel blocker (8), the transient increased ethidium accessibility most likely results from channel opening. The simplest explanation is that the “agonist-activatable” PC/PA-nAChR undergoes rapid Carb-induced conformational transitions that include channel opening and subsequent desensitization.

Effects of Anionic Lipids on Multiple nAChR Conformational Equilibria

Slow ethidium binding to pre-existing desensitized nAChRs is also observed upon mixing PC/PG-nAChR, PC/PI-nAChR, and PC/PS-nAChR with ethidium, but the magnitude of the predesensitized component varies from one PC/anionic lipid membrane to another (Fig. 4). A different proportion of nAChRs is thus stabilized in the pre-existing desensitized state in each PC/anionic lipid membrane. PC/PG-nAChR stabilizes the largest proportion of pre-existing desensitized nAChRs followed by PC/PS-nAChR, PC/PI-nAChR, and finally PC/PA-nAChR.

Even though a relatively large proportion of PC/PG-nAChR is desensitized, the addition of Carb leads to a further increase in fluorescence emission intensity confirming, in agreement with the infrared data, that some receptors are stabilized in an agonist-activatable resting conformation. The Carb-induced increase in fluorescence is rapid and likely reflects transient increased ethidium accessibility to the open state prior to desensitization. In contrast, both PC/PI-nAChR and PC/PS-nAChR show reduced response to Carb. In agreement with the infrared data, the proportion of agonist-activatable resting nAChRs that undergoes channel gating and subsequent desensitization is small in these membranes (see also below).

Relative Proportions of Resting, Desensitized, and Uncoupled nAChRs

To estimate the relative proportions of resting versus desensitized and uncoupled conformations, we studied ethidium binding at ethidium concentrations equivalent to KD, 10× KD, and 100× KD for the desensitized state (∼0.3, ∼3.0, and ∼30 μm, respectively) (Fig. 6). Control kinetic traces show that the uncoupled ion channel of PC-nAChR binds minimal ethidium at these concentrations, although a small amount of ethidium binding to the neurotransmitter sites is observed (see Carb-displaceable fluorescence at 100× KD, Fig. 6, trace v). The uncoupled PC-nAChR has a lower ethidium binding affinity that may be similar to the resting nAChR (∼1 mm).

Increasing concentrations of ethidium shift an increasing proportion of PC/PA-nAChR into the desensitized state. As noted, 50% of the pre-existing desensitized nAChRs bind ethidium at 0.3 μm ethidium concentrations. Conversely, 30 μm ethidium (100× KD for the desensitized state) is sufficient to essentially saturate all desensitized binding sites. The fluorescence intensity observed at 30 μm ethidium in the presence of 500 μm Carb thus reflects ethidium binding to essentially all “coupled” nAChRs, i.e. those pre-existing in both resting and desensitized conformations. The ratio of the dibucaine-displaceable fluorescence intensities observed at 0.3 μm (−Carb) and 30 μm (+Carb) ethidium approximately reflects the ratio of pre-existing desensitized to coupled receptors. From this, the ratio of resting to desensitized (R:D) receptors in PC/PA membranes was estimated to be similar to that found in native membranes (PC/PA-nAChR R:D ≅90:10; native-nAChR R:D ≅85:15) (31, 32). The ratios of resting to desensitized nAChRs in PC/PG-nAChR, PC/PI-nAChR, and PC/PS-nAChR are roughly 35:65, 15:85, and 30:70, respectively. Although these estimates show that PC/anionic lipid membranes have strikingly different abilities to stabilize resting versus desensitized conformations, more comprehensive studies are required to define the precise ratios of resting and desensitized nAChRs in each membrane environment.

Note that the magnitude of the maximal fluorescence intensity observed at 30 μm ethidium in the presence of Carb, which reflects the total number of coupled receptors, also varies substantially from one membrane to another. As uncoupled nAChRs do not bind ethidium appreciably at this concentration, it can be concluded that the different PC/anionic lipid membranes also stabilize different proportions of coupled versus uncoupled receptors.

According to the infrared data, PC/PA-nAChR contains ∼20% fewer agonist-activatable resting nAChRs than PC/PA/Chol-nAChR (Fig. 3). Assuming that this reduction is due to the presence of 20% uncoupled nAChRs, the ratio of resting to desensitized and uncoupled receptors in PC/PA-nAChR is roughly 70:10:20. Comparing the fluorescence data obtained from the other membranes to that of PC/PA-nAChR, the relative proportions of the three conformations in PC/PG-nAChR, PC/PI-nAChR, and PC/PS-nAChR are roughly 15:35:50, 5:20:80, and 10:25:65, respectively.

Although these are rough estimates, they do emphasize the different abilities of the PC/anionic lipid membranes to modulate multiple nAChR conformational equilibria. The estimates also show the close correlation between the infrared and fluorescence data. The number of agonist-activatable receptors in a given reconstituted nAChR membrane, as detected by infrared difference spectroscopy, is dependent upon the ability of that membrane to stabilize resting nAChRs at the expense of both uncoupled and coupled-desensitized nAChRs.

Effects of nAChR on Lipid Packing in the Presence of Anionic Lipids

Finally, one of the interesting features of lipid-nAChR interactions is that lipids not only influence nAChR structure/function, the nAChR also influences the physical properties of the membrane in which it is embedded, and does so in a lipid-selective manner. The nAChR may thus be able to influence the packing of specific lipids into its surrounding micro-environment. Given that the nAChR is thought to be associated with lipid rafts (33, 34), interactions between the nAChR and specific lipids may play an important role in raft association and thus ultimately in trafficking the nAChR to the synaptic membrane. Although not the focus of this study, we did examine the effects of the nAChR on the physical properties of the PC/PG, PC/PI, and PC/cardiolipin membranes (supplemental Figs. S3 and S4 and Table S1). Our data, which are presented and discussed in the supplemental material, show that incorporation of the nAChR leads to an increase in the lateral packing density of all three PC/anionic lipid membranes. Consistent with spin-labeling studies, the nAChR appears to interact preferentially with different anionic lipids (35, 36).

DISCUSSION

Cation flux through the nAChR is usually interpreted in the context of a conformational model involving resting, open, and desensitized states. In this model, the magnitude of an agonist-induced macroscopic flux depends on the relative proportions of pre-existing activatable/resting versus nonactivatable desensitized conformations, as well the ability of an agonist to transition the nAChR to an open state (Fig. 7). The observation that PC-nAChR adopts a distinct uncoupled conformation adds complexity to this conformational scheme (14). The macroscopic response of the nAChR in a reconstituted membrane must be interpreted in terms of a model that includes resting, desensitized, open, and uncoupled conformations (Fig. 7) (14).

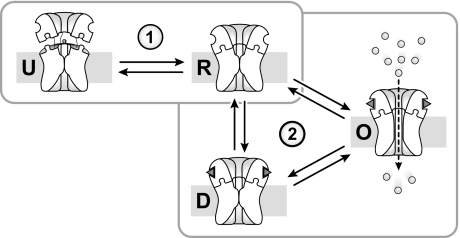

FIGURE 7.

Conformational scheme for the nAChR in reconstituted membranes. The effects of lipids on nAChR function have been interpreted previously using a conformational scheme involving resting (R), open (O), and desensitized (D) conformations (scheme 2). The nAChR in reconstituted membranes can be stabilized in an uncoupled conformation (14). Lipid effects on nAChR function in reconstituted membranes must therefore include equilibria between uncoupled (U) and coupled (R, O, and D) states (scheme 1).

Previous studies have shown that the addition of both PA and Chol to a reconstituted PC membrane stabilizes predominantly a resting nAChR (6, 10, 13, 14). This shows that Chol and PA together modulate the equilibrium between uncoupled and resting conformations (14). We show here that anionic lipids influence the equilibria between uncoupled, resting, and desensitized conformations. Different PC/anionic lipid membranes have different abilities to stabilize the nAChR in an agonist-activatable resting conformation because they have different abilities to stabilize resting over both uncoupled and desensitized states. For example, PC/PA membranes stabilize a large proportion of resting nAChRs because they limit the numbers of both uncoupled and desensitized receptors. PC/PG membranes are less effective at stabilizing an agonist-activatable nAChR because they stabilize a large proportion of both uncoupled and desensitized nAChRs. In contrast, PC/PS and PC/PI membranes are relatively ineffective because both membranes favor the uncoupled state.

The finding that lipids influence multiple nAChR conformational equilibria leads to an important shift in how we both interpret and investigate nAChR-lipid interactions. Many studies have focused on elucidating how specific lipids influence “function,” typically as measured by a single assay that probes the ability of the nAChR to flux cations or undergo an allosteric transition from one conformation to another. This approach implies that there is a single mechanism by which each lipid interacts and thus influences nAChR function.

The fact that lipids influence multiple conformational equilibria, however, raises the possibility that there are a number of mechanisms by which lipids alter function. Lipids may interact preferentially with, and thus preferentially stabilize, either resting, desensitized, or uncoupled conformations. Note that this does not necessarily require distinct lipid-binding sites on each conformation; it may simply suggest that lipids at a single site interact more strongly with one conformation over another. Also, the membrane-exposed surface of the nAChR transmembrane domain may itself act as an “allosteric site,” which is sensitive to bulk membrane mechanical properties, such as hydrophobic mismatch, intrinsic curvature, etc. To understand how lipids influence the proportions of activatable (resting) versus nonactivatable (uncoupled and desensitized) conformations, one must characterize how lipids and different membrane mechanical properties interact with each individual conformational state. In fact, some lipids may have complex interactions with the nAChR in that they preferentially stabilize one conformation by binding to a specific lipid-binding site, while preferentially stabilizing another via effects on bulk membrane mechanical properties.

Although we have studied equilibrium conditions, our fluorescence data also show a rich complexity to the rates of ethidium binding, suggesting that lipids influence the rates of transitions between conformational states. To understand how lipids influence these rates, one must elucidate how lipids interact with transition states to alter the activation energies governing conformational transitions.

The fact that lipids influence multiple conformations also impacts on our understanding of lipid specificity at the nAChR. Some studies have concluded that neutral and anionic lipids are both essential, with considerable research focusing on the role of Chol (6, 8, 37). It has been suggested that Chol and anionic lipids influence nAChR secondary (38, 39) or tertiary/quaternary structure (26, 40). The implication is that lipids are required for the nAChR to “fold” into a native conformation.

The hypothesis that specific lipids are required to stabilize a native structure contrasts with an allosteric model, which implies that lipids interact with and preferentially stabilize pre-existing conformational states. There are many different nAChR conformations in reconstituted membranes. Each of these may interact differently with different lipids or lipid properties. Given the diversity of lipids found in biological membranes and their potentially complex effects on membrane physical properties, it is likely that many lipids influence nAChR conformational equilibria. Although some, such as Chol, may have a greater influence than others, no specific lipid may be absolutely essential for function. In agreement with this hypothesis, all PC/anionic lipid membranes studied here stabilize a proportion of agonist-activatable nAChRs, although the proportions vary substantially from one membrane to another.

The relative efficacies of the PC/anionic lipid membranes for stabilizing an agonist-activatable resting state that undergoes both gating and desensitization are PC/PA > PC/PG > PC/PS > PC/PI ≅ PC/cardiolipin, with the latter two being relatively ineffective. A similar rank potency was found in the efficacy of PA, PS, and PI to stabilize a functional nAChR in reconstituted membranes containing PC and Chol (10). Why do anionic lipids vary in their abilities to stabilize a functional nAChR?

One possible explanation is that the charge distribution within the anionic lipid headgroups may dictate their ability to interact preferentially with the resting conformation. It has been suggested that the nAChR stabilizes PA in a dianionic state and that dianionic PA is particularly effective at stabilizing the nAChR in an agonist responsive conformation (41). A recent study, however, showed the contrary.4 The nAChR stabilizes PA in a reconstituted membrane in the mono-anionic state, possibly by concentrating cations, including protons, at the membrane surface.

Another possible explanation stems from the observation that the efficacy of an anionic lipid is related to the surface area of the headgroup. Those anionic lipids that have smaller headgroup cross-sectional areas (24, 25) are more effective at stabilizing an agonist-activatable resting nAChR (i.e. PA and PG) than those with larger headgroups (PI and PS). For example, one study estimated the relative surface areas of PA, PG, and PC to be 5.20 ± 0.04, 5.48 ± 0.04, and 6.41 ± 0.06 Å2 (24). Lipids with small headgroup surface areas, such as PA and diacylglycerol, exhibit a negative intrinsic curvature (see below), although lipids with larger headgroup, such as PC and PS, exhibit minimal intrinsic curvature (19). The most effective anionic lipid, PA, thus has a substantially smaller headgroup than any other anionic lipid.

The relative cross-sectional areas of the headgroup and acyl chain regions of a phospholipid influences the ability of a lipid to pack effectively into a bilayer (19, 42–44). Lipids with smaller headgroups, such as phosphatidylethanolamine, exhibit inverted cone-like shapes that tend to favor hexagonal phases. When forced into a bilayer, phosphatidylethanolamine leads to curvature stress, a form of potential energy essentially stored within the bilayer. Given that PA (and to a lesser extent PG) has a headgroup that is relatively small, one would expect incorporation of large amounts of PA (or PG) into a planar PC bilayer to result in curvature frustration. In contrast, anionic lipids with headgroups similar in size to that of the PC choline group (i.e. PS and PI) should pack relatively seamlessly into PC bilayers. Curvature frustration may drive transmembrane helix associations leading to effective nAChR coupling. Both anionic lipids and an appropriate physical environment may preferentially stabilize a resting conformation over uncoupled and desensitized nAChRs. Tightly associated lipids have been identified in the crystal structure of a prokaryotic homolog of the nAChR (45). The possible links between membrane mechanical properties and nAChR function require further investigation.

In conclusion, our data show that anionic lipids exhibit strikingly different abilities to stabilize the nAChR in an agonist-activatable resting conformation because they stabilize different proportions of resting, desensitized, and uncoupled states. Bulk membrane physical properties, related to headgroup size, appear to play a role in the efficacies of some anionic lipids. Lipids and membrane physical properties act as allosteric modulators influencing nAChR function by interacting with and preferentially stabilizing native nAChR conformations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Martin Pelchat for the extensive use of the fluorescence spectrometer.

This work was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to J. E. B.) and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Canadian Graduate Scholarship (to C. J. B. D.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6, Table S1, and “Discussion.”

R. M. Sturgeon and J. E. Baenziger, submitted for publication.

- nAChR

- nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- PA

- 1,2-diacyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate

- PC

- 1,2-diacyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- PG

- 1,2-diacyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol

- PI

- 1,2-diacyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoinositol

- PS

- 1,2-diacyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine

- Chol

- cholesterol

- Carb

- carbamylcholine chloride.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sine S. M., Engel A. G. (2006) Nature 440, 448–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen X. M., Deymeer F., Sine S. M., Engel A. G. (2006) Ann. Neurol. 60, 128–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engel A. G., Ohno K., Sine S. M. (2002) Mol. Neurobiol. 26, 347–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrantes F. J. (2004) Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 47, 71–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Criado M., Eibl H., Barrantes F. J. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259, 9188–9198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fong T. M., McNamee M. G. (1986) Biochemistry 25, 830–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan S. E., Demers C. N., Chew J. P., Baenziger J. E. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 24590–24597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rankin S. E., Addona G. H., Kloczewiak M. A., Bugge B., Miller K. W. (1997) Biophys. J. 73, 2446–2455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baenziger J. E., Morris M. L., Darsaut T. E., Ryan S. E. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 777–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamouda A. K., Sanghvi M., Sauls D., Machu T. K., Blanton M. P. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 4327–4337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sunshine C., McNamee M. G. (1992) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1108, 240–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sunshine C., McNamee M. G. (1994) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1191, 59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy M. P., Moore M. A. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 7655–7663 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.daCosta C. J., Baenziger J. E. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 17819–17825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouzat C., Gumilar F., Spitzmaul G., Wang H. L., Rayes D., Hansen S. B., Taylor P., Sine S. M. (2004) Nature 430, 896–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen X. M., Ohno K., Tsujino A., Brengman J. M., Gingold M., Sine S. M., Engel A. G. (2003) J. Clin. Invest. 111, 497–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.daCosta C. J., Ogrel A. A., McCardy E. A., Blanton M. P., Baenziger J. E. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 201–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.daCosta C. J., Wagg I. D., McKay M. E., Baenziger J. E. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 14967–14974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kooijman E. E., Chupin V., Fuller N. L., Kozlov M. M., de Kruijff B., Burger K. N., Rand P. R. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 2097–2102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.daCosta C. J., Baenziger J. E. (2003) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59, 77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reid S. E., Moffat D. J., Baenziger J. E. (1996) Spectrochimica Acta, Part A 52, 1347–1356 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baenziger J. E., Miller K. W., Rothschild K. J. (1992) Biophys. J. 61, 983–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan S. E., Hill D. G., Baenziger J. E. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 10420–10426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickey A., Faller R. (2008) Biophys. J. 95, 2636–2646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elmore D. E. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 144–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Méthot N., Demers C. N., Baenziger J. E. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 15142–15149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baenziger J. E., Darsaut T. E., Morris M. L. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 4905–4911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baenziger J. E., Miller K. W., Rothschild K. J. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 5448–5454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baenziger J. E., Ryan S. E., Goodreid M. M., Vuong N. Q., Sturgeon R. M., daCosta C. J. (2008) Mol. Pharmacol. 73, 880–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herz J. M., Johnson D. A., Taylor P. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 7238–7247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heidmann T., Changeux J. P. (1979) Eur. J. Biochem. 94, 281–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyd N. D., Cohen J. B. (1980) Biochemistry 19, 5344–5353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brusés J. L., Chauvet N., Rutishauser U. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 504–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marchand S., Devillers-Thiéry A., Pons S., Changeux J. P., Cartaud J. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22, 8891–8901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellena J. F., Blazing M. A., McNamee M. G. (1983) Biochemistry 22, 5523–5535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mantipragada S. B., Horváth L. I., Arias H. R., Schwarzmann G., Sandhoff K., Barrantes F. J., Marsh D. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 9167–9175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Criado M., Barrantes F. J. (1984) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 798, 374–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fong T. M., McNamee M. G. (1987) Biochemistry 26, 3871–3880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernandez-Ballester G., Castresana J., Fernandez A. M., Arrondo J. L., Ferragut J. A., Gonzalez-Ros J. M. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 4065–4071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brannigan G., Hénin J., Law R., Eckenhoff R., Klein M. L. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14418–14423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhushan A., McNamee M. G. (1993) Biophys. J. 64, 716–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee A. G. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1666, 62–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alley S. H., Ces O., Barahona M., Templer R. H. (2008) Chem. Phys. Lipids 154, 64–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cullis P. R., Fenske D. B., Hope M. J. (1996) in Biochemistry of Lipids, Lipoproteins and Membranes (Vance D. E., Vance J. E. eds) pp. 1–33, Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bocquet N., Nury H., Baaden M., Le Poupon C., Changeux J. P., Delarue M., Corringer P. J. (2009) Nature 457, 111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.