Abstract

Down-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the mouse leads to progressive and selective degeneration of motor neurons similar to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). In mice expressing ALS-associated mutant superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), VEGF mRNA expression in the spinal cord declines significantly prior to the onset of clinical manifestations. In vitro models suggest that dysregulation of VEGF mRNA stability contributes to that decline. Here, we show that the major RNA stabilizer, Hu Antigen R (HuR), and TIA-1-related protein (TIAR) colocalize with mutant SOD1 in mouse spinal cord extracts and cultured glioma cells. The colocalization was markedly reduced or abolished by RNase treatment. Immunoanalysis of transfected cells indicated that colocalization occurred in insoluble aggregates and inclusions. RNA immunoprecipitation showed a significant loss of VEGF mRNA binding to HuR and TIAR in mutant SOD1 cells, and there was marked depletion of HuR from polysomes. Ectopic expression of HuR in mutant SOD1 cells more than doubled the mRNA half-life of VEGF and significantly increased expression to that of wild-type SOD1 control. Cellular effects produced by mutant SOD1, including impaired mitochondrial function and oxidative stress-induced apoptosis, were reversed by HuR in a gene dose-dependent pattern. In summary, our findings indicate that mutant SOD1 impairs post-transcriptional regulation by sequestering key regulatory RNA-binding proteins. The rescue effect of HuR suggests that this impairment, whether related to VEGF or other potential mRNA targets, contributes to cytotoxicity in ALS.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)2 is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder of motor neurons that inexorably leads to progressive weakness and death. Approximately 10% of ALS cases are familial, and mutation of copper-zinc superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) is the most commonly identified genetic defect (1). Cumulative evidence points to a toxic effect of mutant SOD1 rather than loss of enzyme activity (2). Several mechanisms for this toxic effect have been proposed, including endoplasmic reticulum stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and improper processing of misfolded proteins, but no consensus has been reached (3). We have identified post-transcriptional dysregulation as another mechanism of toxicity by showing that mutant SOD1 expression leads to destabilization and down-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) mRNA (4). VEGF is an essential neuroprotective factor of motor neurons as genetic depletion, independent of SOD1 status, produces an ALS phenotype in mice (5). We previously found that mutant but not wild-type SOD1 was present in the ribonucleoprotein complex associated with adenine- and uridine-rich stability elements (ARE) in the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of VEGF mRNA (4). The 3′-UTR can positively regulate RNA stability and translation, often in response to stressors such as hypoxia and cytokine exposure, through interaction with RNA stabilizers such as Hu Antigen R (HuR) and D (HuD) that bind specifically to the ARE (6–8). Regulation of RNA stability has long been considered a critical pathway in cell response to stress (7, 8). Recently we found that mutant SOD1 acquires a high binding affinity for AREs in the VEGF 3′-UTR and can compete with HuR for VEGF binding (9). In the current study, we show that HuR and the translational regulator, TIA-1-related protein (TIAR), form a complex with mutant but not wild-type SOD1 in transgenic mouse spinal cord and cultured glioma cells. There was sequestration of HuR and TIAR into insoluble aggregates with a concomitant decline in VEGF mRNA binding and a dissociation of HuR from polysomes. Ectopic expression of HuR rescued the adverse effects of mutant SOD1 on VEGF mRNA stability, expression, and cellular function. These findings support a pathogenic role for dysregulation of mRNA processing in mutant SOD1-linked ALS.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

DNA Constructs, Cell Culture, Transfection, and Mouse Tissues

The maintenance, propagation, and transfection of U251 Tet-On cells are described elsewhere (10). The G37R Tet-On clone was prepared identically to the G93A clone (4). For preparation of HuR-SOD1 double clones, inserts for G93A, G37R, and wild-type SOD1 cDNAs, all containing a Flag epitope, were excised with NotI and EcoRV from pcDNA 3.1 (4), and cloned into pcDNA6/Myc-His B vector (Invitrogen). Plasmids were verified by sequencing and then transfected into a HuR Tet-On clone (10) by lipofection. Clones were selected with blasticidin and verified for transgene expression by Western blot using an anti-Flag antibody as described elsewhere (4). Wild-type and G93A transgenic mouse (124-day-old) spinal cord tissues were kindly provided by Dr. Alavaro Estevez.

RNA Kinetics and Endogenous RNA Association

RNA was isolated using RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and quantitated by the RiboGreen fluorometric assay (Invitrogen). For RNA kinetic analysis, we used actinomycin D (ActD) and followed our previously published protocol (4). Degradation curves and estimated half-lives were generated with Graphpad (Graphpad Software). For quantification of endogenous RNA binding, 200 μg of cytosolic and nuclear extracts from cultured cells were prepared using N-PER kit (Pierce Endogen), equally divided into four aliquots and immunoprecipitated with HuR, TIAR, or control IgG using methods described previously (11). The fourth aliquot was used for RNA quantitation. After IP, RNA was eluted from protein G beads using the RNeasy kit and analyzed by qRT-PCR for VEGF mRNA (4). Standard real-time PCR amplification curves were generated (r2 > 0.98) for VEGF mRNA and S9 control using the threshold cycle (Ct) method. GAPDH primers and probe were obtained from Assays on Demand (Applied Biosystems). All qRT-PCR analyses were performed on an ABI 7900 PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems).

Immunoprecipitation, Western Analysis, and ELISA

Cytosolic or whole cell lysates from mouse lumbar spinal cord tissues and cultured cells were prepared in the presence of protease inhibitors and sodium orthovanadate using the T-PER or M-PER kit (Pierce Endogen). 100 μg of cell extract were incubated with 1 μl of antibody overnight at 4 °C. The following antibodies were used: HuR and TIAR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:1000, SOD1 (Stressgen) at 1:1000, and KSRP (kindly provided by Dr. Ching-Yi Chen) at 1:50. Equivalent amounts of control IgG were tested: mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and goat and rabbit IgG (Southern Biotechnology Association). One-fifth of the supernatant served as a loading control. Protein G beads were added, and the antibody-antigen complex was then precipitated, washed, eluted in 1× Laemmli sample buffer (62 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.05% bromphenol blue), and subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis. Western blot analysis was performed as described elsewhere (11). Additional antibodies used were: α-tubulin (Sigma Aldrich) at 1:1500, and actin at 1:1000 (Sigma Aldrich). Band densities were quantified using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). For ELISA analysis, 1 × 104 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and induced with doxycycline (Dox). Secreted VEGF was quantified from the medium using a commercial ELISA kit (4). Total extracts were prepared from each well and quantified using the bicinchoninic acid kit (BCA, Pierce Endogen). All ELISA values were normalized to total protein concentration.

Immunofluorescence Studies

G93A, G37R, and wild-type SOD1 U251 Tet-On clones were seeded on 18-mm coverslips and treated with 0.1 μg/ml Dox for 48 h. Cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 10 min at 25 °C. Fixed cells were blocked in buffer containing 5% fetal bovine serum and 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h at 25 °C and then incubated at 4 °C overnight with the following primary antibodies: Flag (1:300, Cell Signaling), HuR (1:300), and/or TIAR (1:200). Cells were washed in PBS and then incubated at 25 °C for 1 h with secondary antibodies (Invitrogen): Alex fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:100), Alex fluor 568 goat anti-mouse antibody (1:300), and/or Alex fluor 594 donkey anti-goat antibody (1:300). After rinsing in PBS, cells were stained with DAPI (1:20,000) for 5 min and then visualized under an Olympus fluorescence microscope equipped with a digital camera. Monochrome images from each color channel were acquired separately, colorized, and then merged. Fluorescence images were processed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems).

Protein Aggregation Assay

Methods were based on those published elsewhere with some modifications (12). Cells were induced with 0.1 μg/ml Dox for 48 h, washed, and then placed on ice for 15 min in PBS containing 0.5% nonidet P-40, 0.2% digitonin, 0.23 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and a protease inhibitor mixture. Lysed cells were scraped off the plate and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was centrifuged at 55,000 rpm for 1 h at 4 °C to separate insoluble material. The pellet was resuspended in 1× Laemmli sample buffer. Protein concentrations of the supernatants were measured by the BCA assay.

Polysome Gradient Analysis

Polysome gradients were performed based on published methods (13) with minor modifications. Briefly, 5 × 107 cells from wild-type, G93A, and G37R U251 Tet-On clones were cultured in medium with 0.1 mg/ml cycloheximide at 37 °C for 5 min, washed twice with cold PBS containing 0.1 mg/ml cycloheximide, resuspended in 300 μl of PEB lysis buffer (0.3 m NaCl, 15 mm MgCl2, 15 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mg/ml heparin, 0.1 mg/ml cycloheximide) and lysed on ice for 10 min. Lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. Approximately 2.5 mg of cytoplasmic lysate was layered on top of a linear 10–50% (w/v) sucrose gradient and centrifuged in a Beckman SW41 rotor at 35,000 × g for 90 min at 4 °C. Polysome profiles were obtained by absorbance measurements at 260 nm during fraction collection (1 ml each). Equal volumes from each fraction were used for Western blotting (see above) for HuR or ribosomal protein S6 (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). RNA from each fraction was extracted using the RNeasy kit and treated with DNase I. RNA quality was assessed by monitoring 28 S and 18 S rRNA bands on a denaturing agarose gel. VEGF mRNA levels were quantitated and normalized to S9 in the same sample by qRT-PCR.

shRNA-mediated HuR Knockdown

To generate the pLVTHM- shHUR vector, shHuR primers (targeting the sequence TGCCGTCACCAATGTGAAAGT) were annealed and cloned into the Mlu1 and Cla1 sites of the pLVTHM vector. The control pLVTHM plasmid was obtained from Addgene, plasmid 12247. Viral particles were packaged by transfection of 293T cells with either pLVTHM-shHuR or pLVTHM-control together with the virus-packaging plasmids (Addgene plasmid 12259) and (Addgene plasmid 12263), using Lentiphostm HT Transfection Reagent (Clontech). Culture supernatants were collected every 24 h and filtered through the Millex-HV filter unit (Millipore). A total of 106 U251 cells were infected with 2 ml of viral supernatant in a final volume of 4 ml. At 48 h postinfection, cells were washed with DMEM-F12 medium. Protein extracts and RNA from control and shHuR cells were obtained and analyzed.

Proliferation, Cell Viability, and Apoptosis

Cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 in a 96-well plate overnight and induced with various doses of Dox for 48 h. Cells were harvested, and ATP levels were assessed by the ViaLight Plus kit (CAMBREX). This assay measured ATP levels in the lysates by a luciferase-catalyzed production of light from luciferin. Emitted light, which is linearly related to the amount of ATP present in the lysates, was measured in a Spectrafluor Plus machine (Tecan). Cell viability was assessed by Trypan Blue exclusion. For oxidative stress, 225 μm H2O2 was added to the culture medium for 48 h. Apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometry using CytoGLO Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection kit (IMGENEX). Flowjo analytical software (Tree Star) and WinMDI software (Scripps Institute) were used for data analysis.

Statistics

A Student's t test was used for comparing wild type versus each of the mutant clones for endogenous VEGF mRNA binding, expression, cell proliferation, and apoptosis. One-way analysis of variance (with Tukey's multiple comparison test) was used for multiple comparisons within each clone for proliferation and flow cytometry experiments.

RESULTS

HuR and TIAR Colocalize with Mutant SOD1

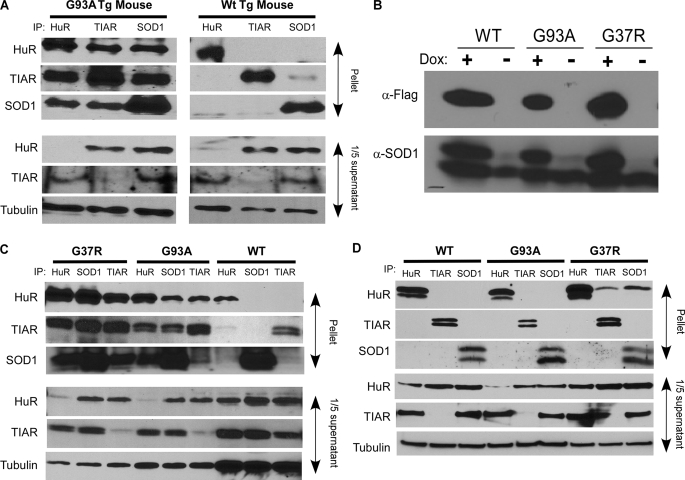

Previously, we observed destabilization of VEGF mRNA in cells expressing G93A SOD1 (4), which suggested that HuR, a major regulator of VEGF mRNA stability, was impaired. One known mechanism of mutant SOD1-induced toxicity is through aberrant interaction with normal cellular proteins (3). To test this possibility, we prepared lysates from spinal cords of normal and G93A mutant mice and performed pull-down assays with antibodies to HuR, TIAR, and SOD1 (Fig. 1A). In G93A spinal cord lysates, we observed coprecipitation of SOD1 with TIAR and HuR antibodies. Similarly, the SOD1 antibody immunoprecipitated HuR and TIAR, confirming the presence of a complex between SOD1, HuR, and TIAR. In wild-type spinal cords, however, there was essentially no coprecipitation with any of the antibodies. Each of the antibodies pulled down its respective target. Supernatants of wild-type and mutant immunoprecipitations (IP) showed equal amounts of HuR, TIAR, and tubulin (lower three panels). IgG controls did not immunoprecipitate any of the targets (supplemental Fig. S1). We next determined if a similar pattern of association occurred in cultured glioma cells expressing SOD1. We tested wild-type, G93A, and G37R SOD1 stably transfected into U251 Tet-On cells (4). After induction with doxycycline, ectopic SOD1 expression was assessed by Western blot using a Flag antibody and found to be similar among the clones (Fig. 1B). Cell lysates were subjected to IP, and like the transgenic spinal cord extracts, each antibody pulled down the HuR-TIAR-SOD1 complex when mutant but not wild-type SOD1 was expressed (Fig. 1C). No proteins were pulled down with IgG (supplemental Fig. S1). We next determined whether the complex could be disrupted by RNA degradation by treating the immunoprecipitates with RNase prior to elution. With G93A, there was total loss of the complex for each antibody (Fig. 1D). For G37R, no colocalization was observed with TIAR or SOD1 antibodies. Faint HuR bands could still be detected with SOD1 and TIAR antibodies, although substantially diminished compared with no RNase treatment. The presence of strong bands for the specific antibody targets suggests that the RNase did not affect the integrity of the antigen-antibody complex or the IP in general. We also tested for the presence of another ARE-RNA-binding protein (ARE-RBP), KH- type splicing regulatory protein (KSRP), which is associated with RNA destabilization (6). IP of lysates from glioma clones using a KSRP antibody did not pulldown HuR, TIAR, or KSRP (supplemental Fig. S2A). Similarly, SOD1, TIAR, and HuR antibodies did not coprecipitate KSRP from glioma cell lysates or transgenic mouse spinal cord extracts (supplemental Fig. S2, B and C). This finding underscores the specificity of the mutant SOD1 complex.

FIGURE 1.

Mutant SOD1 colocalizes with HuR and TIAR. A, pull-down assay with Western blot of lysates from spinal cords of G93A and WT SOD1 transgenic mice. Antibodies used in the immunoprecipitation (IP) are shown at the top, and those used for Western blot to the left. B, Western blot analysis of U251 Tet-On clones stably transfected with Flag-tagged SOD1 plasmids. The blot was probed with anti-Flag and SOD1 antibodies as shown. C, pull-down assay of lysates derived from U251 Tet-On SOD1 clones as described in A. D, same as C except that the immunoprecipitates were treated with RNase A and T1 prior to elution. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

HuR and TIAR Colocalize with Insoluble SOD1 Aggregates

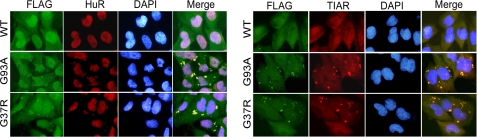

To determine where SOD1, HuR, and TIAR colocalized, we analyzed mutant and wild-type SOD1 glioma clones by immunofluorescence. After Dox induction, cells were stained with a Flag antibody to identify ectopic wild-type or mutant SOD1, and TIAR or HuR antibodies to localize endogenous protein. In mutant clones, we identified cytoplasmic inclusions containing mutant SOD1, HuR, and TIAR (Fig. 2). We further investigated the presence of inclusions/aggregates by biochemical analysis. We prepared cell lysates and separated them into detergent-soluble and -insoluble fractions based on previously published methods (12). As expected, mutant but not wild-type SOD1 was present in detergent-insoluble fractions as detected by an anti-Flag antibody (Fig. 3). We also observed prominent bands for HuR and TIAR in these fractions but not with wild-type SOD1. Both ARE-RBPs were present in soluble fractions with G37R, and to a lesser extent G93A, showing fainter bands than wild-type SOD1. With the tubulin signals equal, this finding is consistent with relocalization of these proteins to the insoluble fraction.

FIGURE 2.

HuR and TIAR colocalize with mutant SOD1 in intracellular inclusions. Immunofluorescence analysis of HuR (left panel set) and TIAR (right panel set) in U251 Tet-On clones induced to express WT, G93A or G37R SOD1 fused to a Flag epitope. Antibodies are depicted at the top.

FIGURE 3.

HuR and TIAR colocalize with mutant SOD1 in detergent-insoluble aggregates. Western blot analysis of detergent soluble and insoluble fractions from U251 SOD1 Tet-On clones induced to express WT or mutant SOD1 (see “Experimental Procedures”). Antibodies used are shown to the left of the blot. These results are representative of three experiments.

Decreased Association of HuR and TIAR with VEGF RNA and the Absence of HuR from Polysomes in SOD1 Mutant Cells

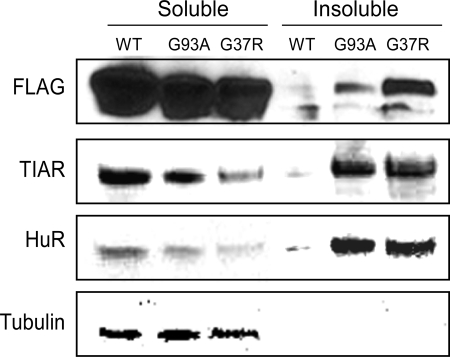

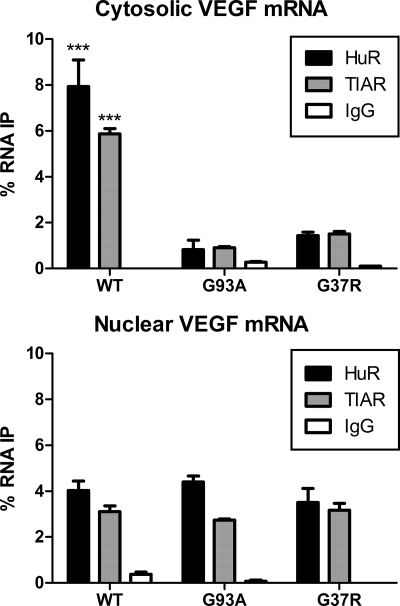

The positive effect of HuR on mRNA stability and translation is linked to increased target mRNA binding and association with polysomes (7, 14–19). Thus, if sequestration of HuR by mutant SOD1 had a significant impact on its function, there should be loss of RNA binding and dissociation from polysomes. To address these possibilities we analyzed endogenous HuR and TIAR binding to VEGF mRNA and the association of HuR with polysomes. We induced the SOD1 clones with Dox and prepared cytoplasmic and nuclear lysates under non-denaturing conditions. Equal amounts of lysate were used for IP with anti-HuR, TIAR, or IgG control antibodies. RNA was extracted from the immunoprecipitate and quantitated for VEGF mRNA by qRT-PCR (Fig. 4). Because overall VEGF mRNA levels are significantly lower in clones expressing mutant SOD1 (4), we expressed the levels as a percent of total VEGF mRNA in the lysate prior to IP. We observed a significant reduction of VEGF mRNA binding to cytosolic HuR and TIAR in mutant compared with wild-type cells (dark bars in graph, p < 0.0001). No significant binding was observed with IgG. In the nuclear compartment, however, there was equivalent binding to HuR and TIAR among all the clones (Fig. 4). No significant pull-down of GAPDH mRNA was observed, indicating the specificity of the IP (supplemental Fig. S3A). To ensure that mRNA was not nonspecifically removed by aggregated mutant SOD1 protein in the preclearing step of IP, we quantitated GAPDH levels in the supernatant after IP and expressed it as a ratio to total GAPDH in the lysate. For both antibodies, we found no significant lowering of the ratio in the mutant clones (supplemental Fig. S3B).

FIGURE 4.

Loss of VEGF mRNA binding to HuR and TIAR in SOD1 mutant cells. Following induction with doxycycline, cytoplasmic, and nuclear lysates from U251 WT, G93A, and G37R SOD1 Tet-On clones were immunoprecipitated with anti-HuR, TIAR, or control IgG antibodies. RNA was extracted from the precipitates and quantified by real-time PCR. Values for cytoplasmic HuR or TIAR were expressed as a percent of total VEGF mRNA present in the lysate. ***, p < 0.0001 comparing WT to G93A and G37R.

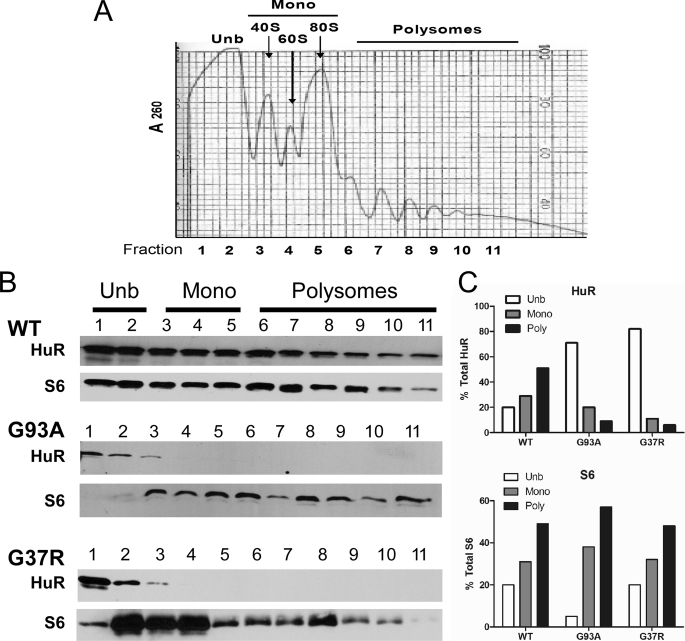

For polysome analysis, we performed sucrose gradient fractionation of cytoplasmic extracts. Fraction collection was monitored by spectrophotometry (Fig. 5A), Western analysis of S6 ribosomal protein (Fig. 5B), and agarose gel electrophoresis of ribosomal RNA (supplemental Fig. S4A). Fractions 1–2 represented non-ribosomal components followed by ribosomal subunits that corresponded to peak levels of 18 S and 28 S rRNAs (fractions 3–5). Fractions 6–11 represented polysomes. In cells expressing wild-type SOD1, HuR was associated with monosomal and polysomal fractions as well as non-ribosomal components (Fig. 5B). In G93A and G37R cells, there was a marked shift of HuR away from mono and polysomal fractions (Fig. 5B). This observation was confirmed by densitometric analysis of HuR bands in each fraction expressed as a percent of total HuR (Fig. 5C). For S6, on the other hand, the distribution was similar among the three clones (Fig. 5C). We also analyzed VEGF mRNA levels and found overall lower levels in the mutant fractions compared with wild-type SOD1 (supplemental Fig. S4B); however, the overall VEGF distribution, based on the percent of total levels within each clone, was similar (supplemental Fig. S4C).

FIGURE 5.

Dissociation of HuR from polysomes in cells expressing mutant SOD1. A, representative polysome profile of a cytoplasmic lysate fractionated by sucrose gradient centrifugation (see “Experimental Procedures”). Profiles for each clone were monitored and found to be similar. From left to right, fractions lacking ribosomes or ribosomal subunits (fractions 1 and 2), fractions that contained ribosome subunits or single ribosomes (fractions 3–5), fractions spanning polysomes of increasing molecular weight (fractions 6–11). B, Western analysis of protein prepared from each of the fractions with antibodies to HuR and the ribosomal protein S6. C, densitometric analysis of HuR and S6 bands from the Western blots shown in B. Values for each protein were totaled and used to calculate the percent of protein present in unbound (Unb) monosomal (mono) or polysomal fractions.

Ectopic HuR Reverses RNA Destabilization and Down-regulation of VEGF

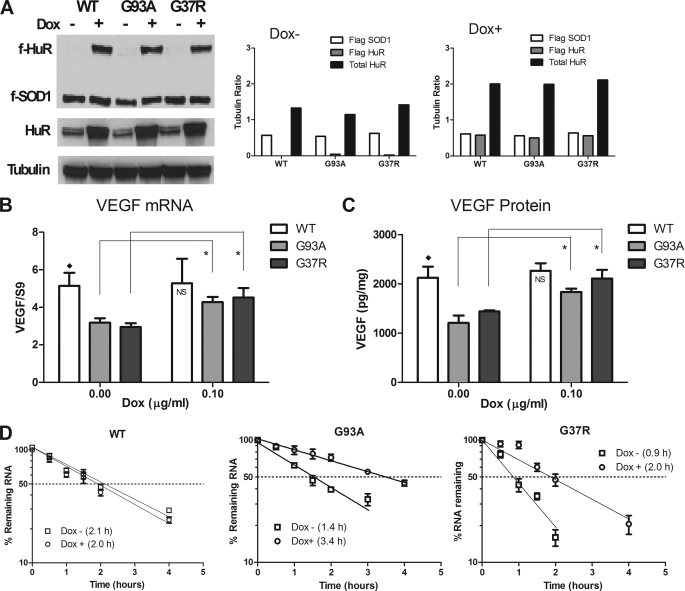

Because the data suggested an inactivation of HuR by sequestration into mutant SOD1 aggregates, we determined whether the adverse effects on VEGF mRNA stability and expression could be reversed by ectopic expression of HuR. A HuR-U251 Tet-On clone was used to test this possibility (10). With Dox treatment, this clone expresses HuR fused to a Flag epitope. We stably transfected these cells with mutant or wild-type SOD1 under the control of a constitutive promoter. Clones were selected for each SOD1 construct and assessed for protein expression by Western blot (Fig. 6A). Because HuR and SOD1 were tagged with Flag, both proteins could be tested in the same blot. Densitometric analysis of band densities indicated similar expression of SOD1, Dox-induced HuR, and total HuR in all clones (Fig. 6A). We next assessed VEGF mRNA and protein expression. At baseline, there was a significant reduction of VEGF mRNA levels in both mutant clones compared with wild-type (Fig. 6B, p < 0.03). With induction of HuR, VEGF mRNA expression significantly increased in the mutant clones compared with baseline (p < 0.03) to a level not significantly different from wild-type SOD1. VEGF protein expression, as assessed by ELISA, followed a similar trend (Fig. 6C). At baseline, protein levels were significantly reduced in mutant clones compared with wild-type (p < 0.04). With HuR induction, there was a significant increase in VEGF protein production (p < 0.02) and the difference with wild-type became nonsignificant. We next assessed the effects of HuR induction on the kinetics of VEGF mRNA (Fig. 6D). Dox-induced or uninduced cells were pulsed with Actinomycin D at different time intervals, and VEGF mRNA levels were quantified by qRT-PCR. Values were expressed as a percentage of VEGF mRNA prior to the pulse. In mutant SOD1 cells, there was a clear separation in curves between Dox-induced and uninduced cells compared with wild-type SOD1. For G37R and G93A, the baseline half-lives (∼0.9 h and 1.4 h, respectively) were similar to what we previously reported in a G93A tet-on clone (4). With G37R, the half-life more than doubled to 1.9 h whereas with G93A the half-life increased by ∼2.6-fold to 3.4 h. VEGF mRNA half-life in wild-type SOD1 remained ∼2.0 h for both conditions. Thus, HuR up-regulation reversed the biochemical effects of mutant SOD1 on VEGF mRNA stability and expression. To determine whether HuR dysfunction alone could explain the biochemical changes, we knocked down HuR by infecting the parent cell (U251 Tet On) and the wild-type SOD1 clone with a lentivirus containing shRNA directed against HuR (supplemental Fig. S5). We achieved 100% transfection efficiency, as determined by fluorescence microscopy, which detected green fluorescent protein in the lentivirus (supplemental Fig. S5A). We obtained excellent knockdown of HuR mRNA and protein (supplemental Fig. S5, B and C) compared with control. We then analyzed VEGF mRNA kinetics and expression (supplemental Fig. S5, D and E). We observed a diminution of half-life in both cell types with HuR knockdown, but did not see any significant declines in VEGF mRNA levels. In fact, control cells showed lower levels than the knockdown cells. These data indicate that the adverse effect of mutant SOD1 on VEGF expression is not solely based on HuR dysfunction.

FIGURE 6.

Reversal of mutant SOD1-induced VEGF down-regulation and destabilization by ectopic HuR. A, Western blot of Dox-induced (0.1 μg/ml) or uninduced U251 cells stably transfected with constitutively expressed Flag-SOD1 and Dox-inducible Flag-HuR. The blot was hybridized with anti-Flag, anti-HuR, and anti-tubulin antibodies as depicted on the left. Band densitometry is shown to the right of the blots. All band densities were expressed as a ratio to the tubulin control. B, analysis of VEGF mRNA expression by qRT-PCR before and after Dox induction. All values were normalized to the housekeeping mRNA, S9, and represent the mean ± S.E. of five independent measurements. ♦, p < 0.03 comparing WT to G93A and G37R at baseline; *, p < 0.03; NS, no significant difference between WT and mutant clones after Dox induction. C, analysis of secreted VEGF by ELISA. Values were normalized to total cellular protein in the well and represent the mean ± S.E. of three independent measurements. ♦, (p < 0.04) comparing WT to G93A and G37R at baseline; *, p < 0.02; NS, no significant difference between WT and the mutant clones after Dox induction. D, analysis of VEGF mRNA kinetics in the SOD1 clones at baseline (Dox−) and following treatment with 0.1 μg/ml of Dox (Dox+). Cells were treated with actinomycin D for the time interval indicated followed by measurement of VEGF mRNA levels using qRT-PCR. All values were expressed as a percentage of baseline RNA levels prior to actinomycin treatment and represent the mean ± S.D. of four independent experiments.

HuR Rescues the Cytotoxic Effects of Mutant SOD1

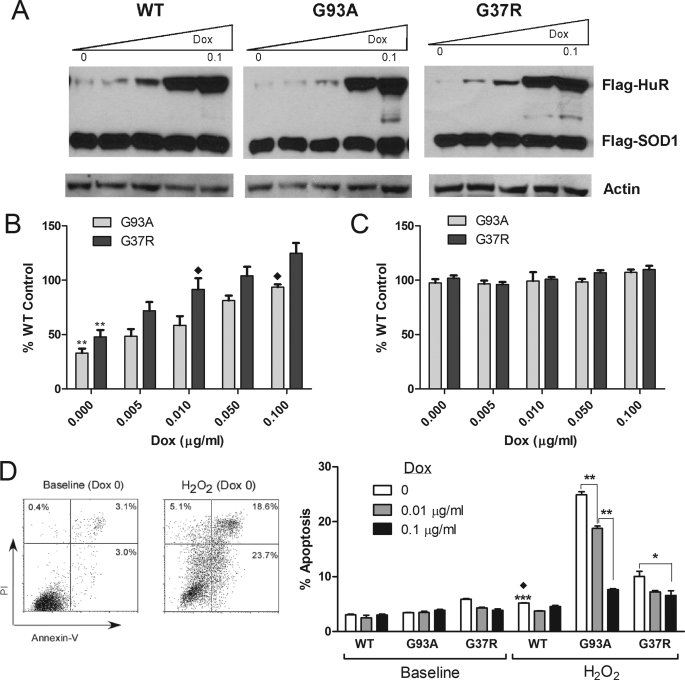

We next investigated cellular toxicity of mutant SOD1 and the potential for reversal by HuR using the SOD1 clones. For these experiments, we chose a range of Dox concentrations (0.01–0.1 μg/ml) that produced a dose-dependent increase in HuR expression (Fig. 7A). Expression of ectopic SOD1, as determined by densitometry, was equivalent in the different clones (supplemental Fig. S6). Ectopic HuR expression in the mutant clones was also equivalent, but somewhat less than wild-type. We first examined the clones for changes in proliferation using a luciferase-based assay (20). In this assay, ATP present in cells drives production of oxyluciferin and light by exogenously added luciferase. This assay reflects cell proliferation and viability, but can also be a measure of mitochondrial function (21, 22). Equal numbers of cells from wild-type, G93A, and G37R clones were induced with Dox at different concentrations for 48 h. Luminescence values for mutant clones were expressed as a percent of the wild-type clone. Under basal conditions we observed significantly decreased luminescence (p < 0.005) in mutant versus wild-type SOD1 clones (Fig. 7B). With increasing doses of Dox, there was a gradual increase in luminescence for both mutant clones. The difference between wild-type and mutant SOD1 clones became nonsignificant at 0.01 μg/ml of Dox for G37R and 0.1 μg/ml for G93A. To determine whether these differences resulted from different cell numbers (i.e. loss of proliferation or cell viability), we performed viable cell counts using Trypan Blue exclusion (Fig. 7C). Dox concentrations and length of induction were identical to the bioluminescence assay. There was no significant difference in viable cell counts among the three clones over the range of Dox concentrations. The finding is consistent with impaired mitochondrial function as previously linked to mutant SOD1 (3, 23). We next produced oxidative stress by adding H2O2 to the culture medium and measured apoptosis by dual flow cytometry using annexin V and propidium iodide. A representative plot is shown for G93A cells before and after H2O2 treatment in the absence of Dox (Fig. 7D, left panel). At baseline, we observed no significant difference among the clones at low or high doses of Dox (Fig. 7D, right panel). With addition of H2O2, however, we observed nearly a 5-fold increase in apoptosis for G93A (p < 0.0001) and 2-fold for G37R (p < 0.007) compared with wild-type SOD1. For G93A, the percent of apoptotic cells progressively and significantly declined with low and high doses of Dox (p < 0.001); however, the difference remained significant compared with wild-type SOD1. With G37R, the percent of apoptotic cells declined significantly at a high dose of Dox (p < 0.05) to a level that was not significantly different from wild-type SOD1. In summary, HuR up-regulation reversed the cytotoxic effects of mutant SOD1 on ATP production and stress-induced apoptosis.

FIGURE 7.

Reversal of mutant SOD1-induced cellular toxicity by HuR. A, Western blot with an anti-Flag antibody showing a Dox dose-dependent induction of Flag-HuR in clones expressing mutant or wild-type SOD1. Dox doses were 0.005, 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1 μg/ml. B, proliferation assay using an ATP-based luciferase system (see “Experimental Procedures”). Equal number of cells were seeded and then induced with Dox for 48 h. Luminescence values for mutant SOD1 clones were expressed as a percentage of wild-type SOD1 at each dose of Dox and are the mean ± S.E. of four independent measurements. **, p < 0.005 compared to wild-type; ♦, indicates loss of significance compared with wild-type SOD1 control. C, cell viability as measured by Trypan Blue exclusion. Experimental conditions were identical to the luminescence experiments. Values were expressed as a percent of wild-type SOD1 control at each Dox dose and represent the mean ± S.E. of two independent experiments, each done in duplicate. D, analysis of oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in SOD1 clones by flow cytometry. The left panel shows a typical result of dual annexin-V and propidium iodide flow cytometry (G93A clone at baseline and with 225 μm H2O2 treatment). The right panel summarizes results of flow cytometry for wild-type and mutant SOD1 clones at baseline and with H202 treatment after different doses of Dox induction. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001; ***, p < 0.0001 (G93A versus wild-type SOD1 with no Dox induction); ♦, p < 0.007 (G37R versus wild-type SOD1 with no Dox induction). Values are the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

HuR and TIAR are essential components of the post-transcriptional apparatus governing localization, translation, and stability of VEGF and other mRNA targets. These molecular pathways are closely connected, and key determinants for regulation are the AREs in the 3′-UTR (6, 7, 18). Typically, HuR, TIAR, and other RNA-binding proteins bind to these elements and modulate mRNA half-life and translation. Because as many as 5–8% of all mRNAs have AREs, the potential impact of ARE-RBPs on cellular function is large (24). We have shown that ALS-associated mutant SOD1 forms a complex with HuR and TIAR with evidence of relocalization to insoluble fractions (Figs. 1–3). This aberrant complex, which we believe is the crux of VEGF post-transcriptional dysregulation, may relate to the RNA binding capability of mutant SOD1. We recently showed that ALS-associated mutations of SOD1, including the ones analyzed here, confer a high binding affinity for AREs in the 3′-UTR of VEGF and other ARE-containing mRNAs in a pattern similar to HuR (9). In that study, mutant SOD1 effectively competed with HuR in vitro for VEGF RNA binding. In the current study, disruption of mutant SOD1 colocalization by RNase treatment suggests that RNA binding is important for complex formation (Fig. 1). VEGF, as with a number of other growth factor and cytokine mRNAs, contains multiple ARE loci within a lengthy 3′-UTR. Different ARE-RBPs, including mutant SOD1, can bind to the ARE concomitantly (4, 9, 25–29). Thus, the RNA ligand may serve as a link between mutant SOD1, HuR, TIAR, and potentially other ARE-RBPs such as hsp70. Mutant SOD1 molecules brought in close proximity, vis-à-vis the 3′-UTR, may promote their oligomerization, aggregation, and the sequestration of nearby ARE-RBPs. The absence of KSRP, an ARE-RBP that was not coprecipitated in mutant or WT SOD1 cells, suggests that RNA bridging is not the sole basis for complex formation (supplemental Fig. S2). Sequestration of cellular proteins has previously been postulated as a mechanism of mutant SOD1 toxicity (3). Examples include heat shock proteins hsp70 and αB-crystallin and the anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-2, all of which coprecipitate with mutant SOD1 or are present in intracellular aggregates (12, 30, 31). From our data, however, we cannot conclude how much HuR or TIAR was sequestered in insoluble fractions.

For VEGF mRNA, the consequences of the aberrant SOD1 complex were 2-fold. First, there was a significant reduction in VEGF mRNA binding to HuR and TIAR in the cytoplasmic but not nuclear compartment (Fig. 4). This dissociation indicates that when these ARE-RBPs cycle into the cytoplasm where mutant SOD1 is located, there is disruption of RNA binding. This may relate to a direct competition with mutant SOD1 for RNA binding or sequestration of the ARE-RBP. The second consequence was a shift of HuR away from polysomes. This depletion occurred even with increased HuR nucleocytoplasmic translocation associated with mutant SOD1 expression (4). For VEGF, HuR typically binds to the ARE and promotes mRNA stabilization and protein up-regulation under certain conditions of cellular stress such as hypoxia, cytokine exposure, glucose deprivation, or oxidative stress (10, 27, 32, 33). Because the positive regulatory effect of HuR is directly related to mRNA binding in the cytosol and its polysomal association (7, 18), our data suggest that the aberrant VEGF kinetics and expression, in part, is related to HuR dysfunction. This observation is further supported by the rescue of VEGF expression with ectopic HuR (Fig. 6). HuR dysfunction, however, is not the sole explanation for the biochemical phenotype, because its silencing did not significantly affect VEGF mRNA levels (supplemental Fig. S5). A similar finding was reported elsewhere for hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α mRNA where silencing of HuR had no effect on its abundance (34). The number of potential targets affected by HuR is broad and includes other ARE-RBPs, such as KSRP, that can negatively regulate mRNAs post-transcriptionally (6, 18, 35, 36). Thus, alternative pathways could be activated because of HuR silencing that restore VEGF mRNA levels. On the other hand, could dysfunction of TIAR, which was in the mutant SOD1 complex and had diminished VEGF mRNA binding, contribute to the biochemical phenotype? TIAR has been shown to bind the VEGF 3′-UTR, but no biochemical phenotype has been described (37). TIAR is associated with stress-induced translational silencing, and thus its dysfunction would be expected to produce an opposite effect on VEGF expression (38). We did not do knockdown experiments to confirm or exclude this possibility. Finally, it is possible that other ARE-RBPs critical for VEGF regulation colocalize to the mutant SOD1 complex and become impaired.

Reversal of the cytotoxic effects of mutant SOD1, including oxidative stress-induced apoptosis, paralleled the biochemical rescue by HuR (Fig. 7). This rescue was dependent on the amount of ectopic HuR expression. When mutant SOD1 cells were not stressed, there was evidence of sublethal mitochondrial dysfunction that was reversed by HuR. Again, the basis for this rescue is likely complex because of the many potential mRNA targets that HuR can affect (6). In fact others have shown that silencing endogenous VEGF or its receptors in glioma cells like the ones used in this study did not affect cell proliferation (39). Thus, restoration of VEGF expression is likely a marker for reversal of other critical factors related to cell survival. In HeLa cells, for example, HuR promotes translation of prothymosin α, a regulator of cell proliferation and inhibitor of the apoptosome, through increased association with the polysome (19). Silencing HuR in that cell system significantly increased apoptosis after UV irradiation whereas ectopic expression was cytoprotective. Likewise, Bcl2 and survivin contain class II AREs that confer mRNA destabilization and down-regulation during apoptosis (40–42). Bcl-2, interestingly, is down-regulated in spinal cord tissues of mice expressing mutant SOD1 (43). Additional analyses are underway to determine whether these potential HuR targets are altered in our cell model.

To date, HuR has been characterized extensively as a positive regulator of cancer cell growth (44). Many of the targets up-regulated by HuR through RNA stabilization and enhanced translation are growth and survival factors critical to tumor progression. ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases, however, are the flipside of cancer where cells die prematurely and tissues atrophy. Impairment of HuR, as we have linked to mutations of SOD1, may accelerate the degenerative process by blocking an essential pathway of stress response and cell survival.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants NS058538, NS064133 (to P. H. K.), NS057664 (to L. L.) from the NINDS, R01 CA112397 (to L. B. N.) from the NCI, and a Merit Review award from the Dept. of Veterans Affairs (to P. H. K.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6.

- ALS

- amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ARE

- adenine- and uridine-rich element

- ARE-RBP

- ARE-RNA-binding protein

- Dox

- doxycycline

- ELAV

- embryonic lethal abnormal visual

- HuR

- Hu antigen R

- IL

- interleukin

- KSRP

- KH-type splicing regulatory protein

- RNP

- ribonucleoprotein

- SOD

- copper/zinc superoxide dismutase

- TIAR

- TIA-1-related protein

- TNF-α

- tumor necrosis factor α

- TTP

- tristetraprolin

- UTR

- untranslated region

- VEGF

- vascular endothelial growth factor

- WT

- wild-type

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosen D. R., Siddique T., Patterson D., Figlewicz D. A., Sapp P., Hantati A., Donaldson D., Goto J., O'Regan J. P., Deng H. X. (1993) Nature 362, 59–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruijn L. I., Houseweart M. K., Kato S., Anderson K. L., Anderson S. D., Ohama E., Reaume A. G., Scott R. W., Cleveland D. W. (1998) Science 281, 1851–1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boillée S., Vande Velde C., Cleveland D. W. (2006) Neuron 52, 39–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu L., Zheng L., Viera L., Suswam E., Li Y., Li X., Estévez A. G., King P. H. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 7929–7938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oosthuyse B., Moons L., Storkebaum E., Beck H., Nuyens D., Brusselmans K., Van Dorpe J., Hellings P., Gorselink M., Heymans S., Theilmeier G., Dewerchin M., Laudenbach V., Vermylen P., Raat H., Acker T., Vleminckx V., Van Den Bosch L., Cashman N., Fujisawa H., Drost M. R., Sciot R., Bruyninckx F., Hicklin D. J., Ince C., Gressens P., Lupu F., Plate K. H., Robberecht W., Herbert J. M., Collen D., Carmeliet P. (2001) Nat. Genet. 28, 131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barreau C., Paillard L., Osborne H. B. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 7138–7150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan C. M., Steitz J. A. (2001) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58, 266–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross J. (1995) Microbiol. Rev. 59, 423–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X., Lu L., Bush D. J., Zhang X., Zheng L., Suswam E. A., King P. H. (2009) J. Neurochem. 108, 1032–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nabors L. B., Suswam E., Huang Y., Yang X., Johnson M. J., King P. H. (2003) Cancer Res. 63, 4181–4187 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suswam E. A., Nabors L. B., Huang Y., Yang X., King P. H. (2005) Int. J. Cancer 113, 911–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shinder G. A., Lacourse M. C., Minotti S., Durham H. D. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 12791–12796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawai T., Fan J., Mazan-Mamczarz K., Gorospe M. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 6773–6787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lal A., Mazan-Mamczarz K., Kawai T., Yang X., Martindale J. L., Gorospe M. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 3092–3102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallouzi I. E., Brennan C. M., Stenberg M. G., Swanson M. S., Eversole A., Maizels N., Steitz J. A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3073–3078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doller A., Pfeilschifter J., Eberhardt W. (2008) Cell. Signal 20, 2165–2173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keene J. D. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 7018–7024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdelmohsen K., Kuwano Y., Kim H. H., Gorospe M. (2008) Biol. Chem. 389, 243–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lal A., Kawai T., Yang X., Mazan-Mamczarz K., Gorospe M. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 1852–1862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crouch S. P., Kozlowski R., Slater K. J., Fletcher J. (1993) J. Immunol. Methods 160, 81–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slater K. (2001) Curr. Opin. Biotech. 12, 70–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keil U., Scherping I., Hauptmann S., Schuessel K., Eckert A., Müller W. E. (2006) Br. J. Pharmacol. 147, 199–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasinelli P., Brown R. H. (2006) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 710–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakheet T., Williams B. R., Khabar K. S. (2006) Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D111–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen C. Y., Shyu A. B. (1995) Trends Biochem. Sci. 20, 465–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy A. P., Levy N. S., Wegner S., Goldberg M. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 13333–13340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy N. S., Chung S., Furneaux H., Levy A. P. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6417–6423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakheet T., Frevel M., Williams B. R., Greer W., Khabar K. S. (2001) Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 246–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King P. H. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28, E20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okado-Matsumoto A., Fridovich I. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 9010–9014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pasinelli P., Belford M. E., Lennon N., Bacskai B. J., Hyman B. T., Trotti D., Brown R. H., Jr. (2004) Neuron 43, 19–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cherradi N., Lejczak C., Desroches-Castan A., Feige J. J. (2006) Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 916–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yun H., Lee M., Kim S. S., Ha J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9963–9972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galbán S., Kuwano Y., Pullmann R., Jr., Martindale J. L., Kim H. H., Lal A., Abdelmohsen K., Yang X., Dang Y., Liu J. O., Lewis S. M., Holcik M., Gorospe M. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 93–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pullmann R., Jr., Kim H. H., Abdelmohsen K., Lal A., Martindale J. L., Yang X., Gorospe M. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 6265–6278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim H. H., Gorospe M. (2008) Cell Cycle 7, 3124–3126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suswam E. A., Li Y. Y., Mahtani H., King P. H. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 4507–4518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Förch P., Valcárcel J. (2001) Apoptosis 6, 463–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong X., Jiang F., Kalkanis S. N., Zhang Z. G., Zhang X., Zheng X., Mikkelsen T., Jiang H., Chopp M. (2007) J. Exp. Ther. Oncol. 6, 219–229 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schiavone N., Rosini P., Quattrone A., Donnini M., Lapucci A., Citti L., Bevilacqua A., Nicolin A., Capaccioli S. (2000) FASEB J. 14, 174–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lapucci A., Donnini M., Papucci L., Witort E., Tempestini A., Bevilacqua A., Nicolin A., Brewer G., Schiavone N., Capaccioli S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 16139–16146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mita A. C., Mita M. M., Nawrocki S. T., Giles F. J. (2008) Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 5000–5005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vukosavic S., Dubois-Dauphin M., Romero N., Przedborski S. (1999) J. Neurochem. 73, 2460–2468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.López de Silanes I., Lal A., Gorospe M. (2005) RNA Biol. 2, 11–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.