Abstract

Osteoclasts are multinucleated giant cells with bone resorbing activity. We previously reported that the expression of the transcription factor NFAT2 (NFATc1) induced by receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) is essential for the formation of multinucleated cells. We subsequently identified l-Ser in the differentiation medium as necessary for the expression of NFAT2. Here we searched for serine analogs that antagonize the function of l-Ser and suppress the formation of osteoclasts in bone marrow as well as RAW264 cells. An analog thus identified, H-Ser(tBu)-OMe·HCl, appeared to suppress the production of 3-ketodihydrosphingosine by serine palmitoyltransferase, and the expression and localization of RANK, a cognate receptor of RANKL, in membrane lipid rafts was down-regulated in the analog-treated cells. The addition of lactosylceramide, however, rescued the osteoclastic formation. When administered in vivo, the analog significantly increased bone density in mice and prevented high bone turnover induced by treatment with soluble RANKL. These results demonstrate a close connection between the metabolism of l-Ser and bone remodeling and also the potential of the analog as a novel therapeutic tool for bone destruction.

Introduction

Osteoclasts are multinucleated giant cells with bone resorbing activity and play a key role in bone remodeling in conjunction with osteoblasts (1, 2). It is well established that receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) plays a central role in osteoclastogenesis through its cognate receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK) (3, 4). We previously found, using an in vitro model of osteoclastogenesis consisting of mouse cells and recombinant RANKL, that the expression of the transcription factor NFAT2 (NFATc1) induced by stimulation with RANKL is essential for the formation of mature osteoclasts (5). Interestingly, culture at high cell density in the in vitro differentiation system blocked progression to the multinucleated (MN)3 cell stage. Subsequently, a high cell density was found to cause a change in the composition/state of the culture medium accompanying down-regulation of NFAT2 expression, and we eventually identified l-Ser as a key component for the phenomenon (6). Although the differentiation medium contained seven nonessential amino acids (l-Ala, l-Asn, l-Asp, l-Glu, l-Gly, l-Pro, and l-Ser), no other amino acid showed such a characteristic property. In fact, no osteoclasts formed when only l-Ser was depleted from the differentiation medium with dialyzed serum. In this regard, d-Ser was completely inert, and moreover, when d-Ser was added together with l-Ser, there was a suppressive effect on NFAT2 expression/osteoclastic formation, implying certain analog(s) to be useful for suppressing osteoclastogenesis through the down-regulation of NFAT2 expression. Unfortunately, however, d-Ser had a toxic effect in RAW264 cells.

Here we systematically searched for analogs with more effective suppressive activity and less toxicity. We consequently identified a novel serine analog, H-Ser(tBu)-OMe·HCl (or O- t.-Butyl-l-serine methyl ester hydrochloride), that suppressed osteoclastogenesis in vitro by down-regulating RANK expression as well as its localization in membrane lipid rafts and the subsequent RANKL/RANK signaling cascade. The analog appeared to inhibit the production of 3-ketodihydrosphingosine (KDS) by serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT), and the addition of lactosylceramide (LacCer) rescued the osteoclastic formation. The analysis using the analog thus shed light on the significance of serine metabolism through SPT in osteoclastogenesis. Moreover, this effect was confirmed in vivo; namely, administration of the analog appeared to increase bone density in control mice and to prevent high bone turnover in soluble RANKL-treated mice. Therefore, the findings may be useful for developing a novel therapeutic tool for bone diseases such as osteoporosis, which is known to be accelerated by enhanced bone resorbing activity and/or the formation of osteoclasts. The significance of the findings is discussed.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and Reagents

RAW264 cells were cultured in Eagle's minimum essential medium (Nissui, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), 0.1 mm l-glutamine (Nissui), and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). GST-RANKL was prepared as described previously (5). Anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (AC-74) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Rabbit anti-ERK, anti-pERK, anti-p38, and anti-phosphop38 were from Promega and Cell Signaling Technology, respectively. Anti-RANK antibody (sc-9072), anti-NFAT2 monoclonal antibody (sc-7294), and anti-c-Fos (sc-52) rabbit polyclonal antibody were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated protein A were purchased from GE Healthcare UK Ltd. FB1 and myriocin were obtained from Calbiochem. LacCer and H-Ser(tBu)-OMe·HCl were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Merck, respectively.

Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of d-Ser or analog was assessed with a WST-8 assay kit (TAKARA BIO, Shiga, Japan). The cells were incubated in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well in triplicate in the presence of increasingly higher concentrations of d-Ser or the analog. After 72 h, 10 μl of the solution provided with WST-8 was added to each well, and the cells were cultured for another 2 h. The absorbance of each well was measured at 450 nm.

Isolation of Bone Marrow Cells and Osteoclastogenesis

For examining osteoclastogenesis in vitro, either RAW264 cells or bone marrow macrophages were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 cells/ml and incubated for 24 h. Purified GST-RANKL or GST, prepared as described (5), was added to the culture medium at a final concentration of 400–500 ng/ml (RANKL) or 200 ng/ml (GST). The medium was replaced every 3 days with Eagle's medium containing RANKL or GST. Bone marrow macrophages were prepared as described previously (7) with some modifications. In brief, bone marrow cells were collected by flushing the femurs and tibias of 6–8-week old wild-type mice with α-minimum essential medium (Invitrogen), and red blood cells were removed by treatment with ammonium chloride solution. After being washed, the cells were cultured in α-minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% conditioned medium of NIH3T3/pCAhMCSF cells (macrophage colony-stimulating factor conditioned medium) (6). After 12–16 h, nonadherent cells were collected and cultured a further 1–3 days in α-minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 3% macrophage colony-stimulating factor conditioned medium.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

The cells were lysed with radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS, 150 mm NaCl, and 1 mm EDTA) containing 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mm Na3VO4, 20 mm NaF, and 100 KIU/ml aprotinin. Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting were carried out essentially as described using protein A-Sepharose (GE Healthcare Bioscience KK, Tokyo, Japan). The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, MA), and detected by Western blotting using Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent horseradish peroxidase substrate (Millipore).

Preparation of Membrane Lipid Rafts

This was essentially performed as reported (8). Flotilin was used as a raft marker protein.

Screening of Serine Analogs

We tested ∼100 types of l-serine analogs including dipeptides. Substances that either caused cell death or showed osteoclast inducing activity were eliminated at the first screening. The candidates were then added at concentrations of 0.1, 1, and 10 mm to the in vitro osteoclastogenesis system as described above, and the numbers of TRAP-positive multinucleated cells formed were counted after 4 days.

Tests of Acute Toxicity in Mice

Test substances were administered intraperitoneally to a group of female mice (n = 5). The dose levels were selected in such a way that 0–100% of the animals would die. The LD50 with 95% confidence limits and function was determined as described (9).

Induction of High Bone Turnover in Mice

This was carried out essentially as described (10, 11). Female C57BL/6JJc1 mice, aged 7 weeks, were intraperitoneally injected with 100 μg of GST or GST-RANKL three times at intervals of 24 h. The l-Ser analog (analog 290) was injected twice a day with the first injection 1 h before the GST-RANKL treatment, and the second injection was 8 h after the first. One day after the last injection, all of the mice were sacrificed and subjected to pQCT and micro-CT analyses.

Micro-CT Analysis

Right tibiae were dissected out from 6–8-week old female mice of vehicle-, RANKL-, or analog 290-treated mice and stored in 70% ethanol. The imaging of proximal metaphyses of the tibiae was performed by micro focus x-ray computed tomography (Scan X-mate; Comscan Techno). Three-dimensional micro-CT images were analyzed and quantified using TRI/3D-BON image analysis software (Ratoc System Engineering).

Bone Histomorphometry

Histomorphometric parameters on proximal metaphyses of left tibiae were measured at the Ito Bone Histomorphometry Institute (Niigata, Japan) and described according to the nomenclature system (12).

pQCT

The right tibiae were dissected out from mice to be examined as described above and stored in 70% ethanol. The proximal metaphysis and midshaft of each tibial sample were scanned with a peripheral quantitative computer tomography (pQCT) system (XCT Research SA; Norland Stratec Medizintechnik GmbH). The growth cartilage at the distal epiphysis of the tibia was used as a reference line, and two sites, at 1 and 7 mm medial to the line, were selected as the point of the analysis for trabecular BMD and cortical BMD, respectively. The following set-up was used for the measurement; voxel size = 0.08 mm, slice thickness = 0.46 mm, contour mode = 2, peel mode = 2, inner threshold for trabecular bone analysis = 395 mg/cm3, cortical mode = 1, and threshold for cortical analysis = 690 mg/cm3.

Preparation of SPT and SPT Assay

Cell and microsomal fractions containing SPT were prepared from CHO-K1 cells and LY-B cells (as a negative control of SPT activity) and mouse tissues, respectively (14–16). CHO-K1 cells were cultivated in spinner bottles containing 1 liter of ES medium (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine, NaHCO3 (1 g/liter), 10 mm Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.4), and 5% (v/v) FBS at 37 °C. The membrane fraction was prepared essentially as described previously (14). The presence of SPT was monitored by Western blotting using anti-SPT antibody (Cayman Chemical, MI). For mouse tissues, the mice were killed by cervical dislocation, and the liver, kidney, and lung were removed, minced with scissors, and homogenized with a glass homogenizer under isotonic conditions with Hepes (pH 7.4), sucrose, and EDTA. The microsomal pellet was prepared by serial centrifugation and finally suspended in 1 ml/g of tissue with 50 mm Hepes (pH 7.4), 5 mm EDTA, 5 mm dithiothreitol, and 20% (w/v) glycerol and stored at −80 °C (13). Either the cell or microsomal fraction containing SPT was incubated in 200 μl of a standard SPT reaction buffer (50 mm Hepes-NaOH buffer, pH 7.5, containing 5 mm EDTA, 5 mm dithiothreitol, 50 μm pyridoxal phosphate, 25 μm palmitoyl-CoA, and 0.1 mm l-Ser) at 37 °C for 10 min; for labeling of the product, either l-[3H]Ser (50 mCi/mmol: Amersham Biosciences, NJ) or [14C]palmitoyl-CoA (Amersham Biosciences) was used. After the reaction was stopped, the lipids were extracted, and the radioactively labeled KDS was measured as described (14, 15).

Ethics

The mice were purchased from CLEA Japan Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) and bred and maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the Nara Institute of Science and Technology Animal Ethics Committee.

RESULTS

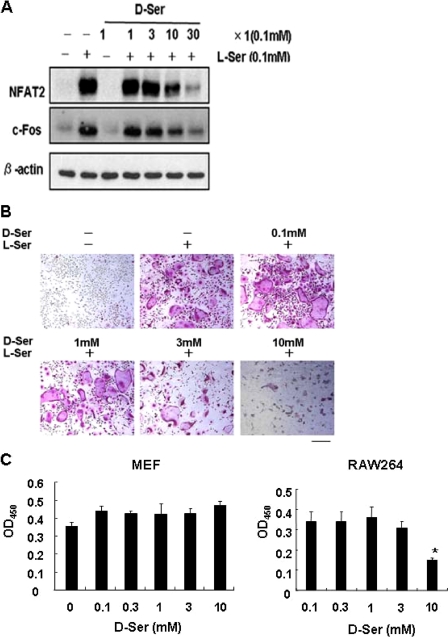

l-Ser Is Indispensable for Osteoclasts to Form in Vitro, and d-Ser Cancels Out the Effect of l-Ser

We reported previously that l-Ser was indispensable for osteoclasts to form in vitro (6). Namely, when l-Ser was depleted from the regular medium, the expression of c-Fos as well as NFAT2 was significantly down-regulated in both RAW264 cells and bone marrow macrophages. Conversely, the addition of l-Ser without another NEAA restored the expression of NFAT2, and the retroviral transfer of NFAT2 appeared to compensate for the depletion of l-Ser (6). Regarding this, d-Ser was found to be unable to substitute for l-Ser, and instead, when d-Ser was added together with l-Ser up to a 390-fold excess, there was a suppressive effect on NFAT2/c-Fos expression (Fig. 1A). In fact, when the effect of d-Ser was monitored by the formation of TRAP-positive MN cells, only a few corresponding cells were observed in the presence of 3 mm d-Ser, and even entire viable cells became limited with 10 mm d-Ser (Fig. 1B), suggesting the toxicity of d-Ser. This inhibitory effect of d-Ser was unique to osteoclastic cells in that it little influenced the proliferation of mouse embryonic fibroblasts even in the presence of 10 mm d-Ser (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Competitive effect of d-Ser on formation of osteoclasts and expression of c-Fos/NFAT2. A, effects of d-Ser on c-Fos and NFAT2. RAW264 cells were cultured for 4 days after RANKL treatment in the absence or presence of 0.1 mm l-Ser and various amounts of d-Ser as indicated. The cell extracts were prepared, and the expression of c-Fos and NFAT2 was monitored by Western blotting. Anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody was used for monitoring the amount of protein applied. B, effects of d-Ser on MN cell formation. RAW264 cells were cultured for 4 days after RANKL treatment under regular conditions except for the absence or presence of 0.1 mm l-Ser with the indicated amount of d-Ser. The morphology of TRAP-stained cells is shown. Bar, 200 μm. C, effects of d-Ser on proliferation or survival of MEF and RAW264 cells. Indicated concentrations of d-Ser were included in the medium for the culture of MEF or RAW264 cells as described under “Experimental Procedures.” *, p < 0.05.

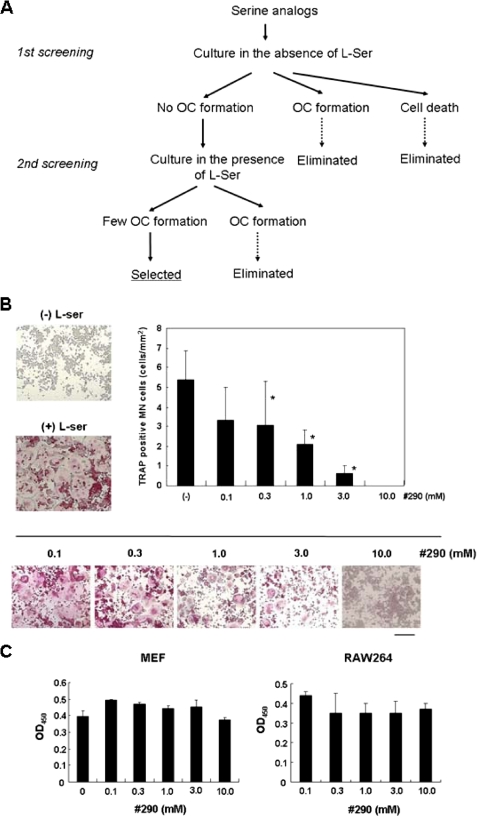

Search for Antagonists of l-Ser and Identification of Analog 290

The above results implied that compounds with antagonistic activity against l-Ser might be useful for modulating osteoclastogenesis. However, because d-Ser showed toxicity to preosteoclastic cells (Fig. 1B), we conducted a systematic search focusing on serine analogs with effective suppressive activity but less toxicity.

To this end, we tested ∼100 substances according to the procedure shown in Fig. 2A. The analogs could be classified into three groups based on their characteristics at the first screening step: namely, (i) those that could substitute for l-Ser and formed MN cells, (ii) those that caused cell death, and (iii) those that did not affect cell viability but little influenced the formation of TRAP-positive MN cells. We then examined the inhibitory activity of the third group in the presence of l-Ser. H-Ser(tBu)-OMe·HCl, given analog 290, showed the most desirable properties in terms of solubility in water and effects on differentiation and viability and was mainly used in subsequent experiments. Actually, as shown in Fig. 2B, the addition of analog 290 to the regular differentiation system significantly suppressed the formation of TRAP-positive MN cells but had little effect on the proliferation or viability of MEF and RAW264 cells at 10 mm, in contrast to d-Ser (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Identification of analogs with an inhibitory effect on osteoclastogenesis. A, schematic diagram of the screening strategy. RAW264 cells were cultured under regular conditions in the absence of l-Ser together with 0.1 mm of each substance to be tested for the first screening. Cell morphology was judged after 4 days. Substances that produced few TRAP-positive MN cells were subjected to further screening. At the second screening, RAW264 cells were cultured in the presence of 0.1 mm l-Ser together with various concentrations (0.1–3.0 mm) of candidate substances, and cell morphology was examined after 4 days. B, concentration-dependent effect of analog 290 on MN cell formation. Bone marrow cells were prepared and induced to form MN cells in the presence of each substance at the indicated concentration, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The morphology of cells and numbers of TRAP-positive MN cells are shown. *, p < 0.05 versus analog 290-free condition. Bar, 200 μm. C, effects of analog 290 on proliferation or survival of MEF and RAW264 cells. These were carried out as described for Fig. 1C.

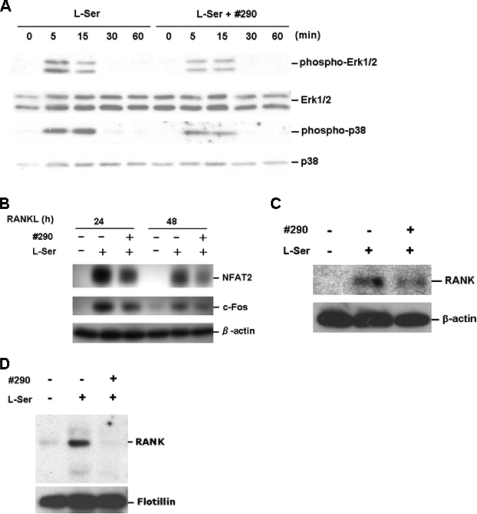

Analog 290 Modulates RANK Expression and Down-regulates the RANKL/RANK Signaling Cascade

RANKL is known to activate a signaling cascade leading to the induction of NFAT2 expression/activity, and MAPK and c-Fos play essential roles in this cascade (16). Actually, l-Ser-depleted conditions caused the down-regulation of this cascade (Ref. 6 and Fig. 1A). When 3 mm of analog 290 was included in the regular reaction mixture, the activation of ERK and p38 as well as the expression of c-Fos and NFAT2 were found to be significantly down-regulated (Fig. 3, A and B), suggesting that the analog functions by suppressing the RANKL/RANK signaling cascade under conditions similar to those caused by the depletion of l-Ser. Regarding this, the expression of RANK was found to be down-regulated in the analog-treated cells (Fig. 3C), and moreover, its localization in membrane lipid rafts appeared to be significantly reduced (Fig. 3D). Overall, it is conceivable that this down-regulation causes the suppression of the downstream signaling machinery.

FIGURE 3.

Effects of the analog on RANKL signaling cascade. A, RAW264 cells were cultured in the presence of l-Ser (0.1 mm) without analog 290 (left panel) and with (right panel) 3 mm of the analog, respectively, for the periods indicated after RANKL treatment. Cell lysate was prepared, and the expression and phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 were monitored by Western blotting, using anti-ERK, anti-pERK, anti-p38, and anti-pp38 antibodies, respectively. B, RAW264 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 0.1 mm l-Ser and analog 290 (3 mm), and cell lysate was prepared at 24 h after RANKL treatment. The expression of c-Fos and NFAT2 was monitored by Western blotting, using anti-Fos and anti-NFAT2 antibody, respectively. Anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody was used for monitoring the amount of protein applied. C, effect of analog 290 on RANK. RAW264 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 0.1 mm l-Ser and 3 mm analog 290 for 24 h as indicated at the top of the panel, then stimulated with RANKL, and cultured for another 24 h. Cell lysate was prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures” and immunoprecipitated using anti-RANK antibody, followed by Western blotting using the same antibody. Anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody was used for monitoring the amount of protein applied. D, localization of RANK in membrane lipid rafts. The cells were prepared as in C, and the membrane lipid rafts were prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures.” RANK was detected as in C.

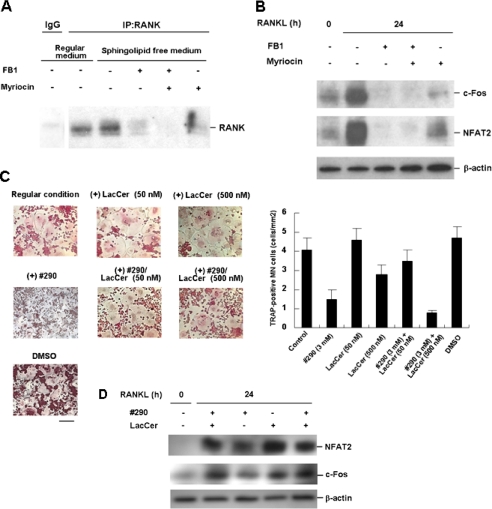

l-Ser Metabolism Is Important for Osteoclastogenesis, and the Analog Inhibits KDS Production by SPT

To understand the functional mechanism of the analog, we examined the effect of its dosage on the metabolism of l-Ser. l-Ser is known to be metabolized to ceramide/sphingolipids in mammalian cells through the condensation of serine and palmitoyl-CoA by SPT as a first step, producing KDS. In this regard, an important role for glycosphingolipid in osteoclastogenesis was reported (17). The involvement of this pathway in the formation of MN cells was actually confirmed in our system using myriocin, an SPT inhibitor. When 1.0 μm of myriocin was added to the RAW264 cells, the expression of c-Fos and NFAT2 as well as RANK was found to be significantly down-regulated (Fig. 4, A and B), suggesting that the metabolism of l-Ser through SPT plays an essential role in the activation of the RANKL/RANK signaling cascade. Because l-Ser was present in the medium, the results obtained with the use of myriocin also suggested that l-Ser per se does not act directly. Moreover, FB1, an inhibitor of ceramide synthase acting at the salvage pathway of ceramide synthesis as well as at the second last step of the de novo synthesis pathway, had a similar effect to myriocin on c-Fos, NFAT2, and RANK. These results, combined with those in Fig. 3, strongly suggested that metabolites, in particular ceramide and/or its derivatives, play a role in the activation of the RANKL/RANK signaling cascade through the modulation of RANK expression.

FIGURE 4.

Role of l-Ser metabolism in RANK/RANKL signaling. A, effects of myriocin and FB1 on RANK expression. RAW264 cells were cultured under regular conditions using 10% FBS. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with one containing sphingolipid-free serum instead of normal FBS and also either 1 μm myriocin or 50 μm FB1, and incubation continued for another 24 h. Immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blotting were done as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Normal mouse IgG was used as a control. B, effects of myriocin and FB1 on c-Fos and NFAT2 expression. The cell culture and preparation of cell lysate were carried out as in A. Western blotting was then carried out using anti-c-Fos and anti-NFAT2 antibodies. C, LacCer rescues the analog-treated cells. RAW264 cells were cultured under regular conditions containing 0.1 mm l-Ser in the absence or presence of 50 or 500 nm LacCer and 3 mm analog 290 for 4 days. The morphology is shown (left panels). Bar, 200 μm. The numbers of TRAP-positive MN cells were counted. The data are the means ± S.E. for three independent experiments (right panel). D, effects of LacCer on the expression of c-Fos and NFAT2 in RAW264 cells. RAW264 cells were cultured under regular conditions in the absence or presence of 1 mm analog 290 for 24 h. The expression of c-Fos and NFAT2 before and after RANKL treatment was examined by Western blotting.

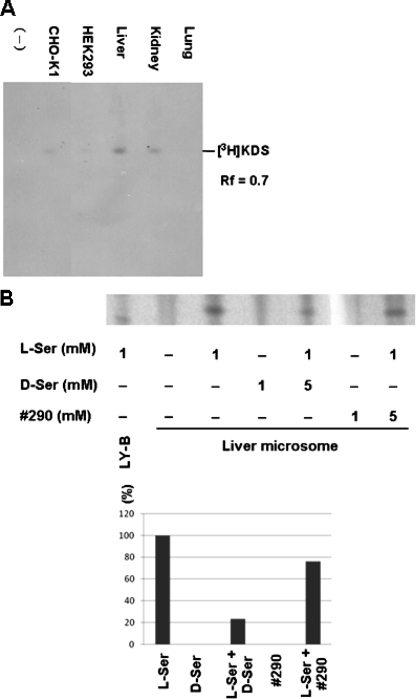

To test the involvement of SPT as a target of analog 290 more directly, we purified SPT and examined the effect of the analog on the formation of KDS. As shown in Fig. 5A, we measured the production of KDS using [14C]palmitoyl-CoA as a substrate. When 1 mm l-Ser was included in the reaction mixture containing the microsomal fraction of mouse liver, the production of KDS was clearly observed, in contrast to the fraction from LY-B cells, which are known to lack SPT activity (18). Neither d-Ser nor the analog produced KDS, and when a 5-fold excess of either was added together with l-Ser, the production of KDS was reduced to 20 and 75% of the control level, respectively (Fig. 5B); a 5-fold excess of neither d-Ser nor analog 290 was a saturated concentration (data not shown). Regarding this, d-Ser was reported to inhibit KDS production in a competitive manner (19). Together, the analog seems to function at SPT reducing l-Ser metabolism, affecting osteoclastogenesis. In fact, when LacCer, a glycosphingolipid, was added exogenously to the analog-treated cells, the formation of TRAP-positive MN cells recovered (Fig. 4, C and D).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of analog 290 on SPT activity. A, enzymatic activity of SPT in microsomal fractions prepared from several cell lines and mouse tissues. Microsomal fractions were prepared, and SPT activity was measured as described previously (14). [3H]l-Ser was used as a substrate in a reaction mixture containing palmitoyl-CoA with or without the microsomal fraction as indicated at the bottom, and the production of KDS was observed at Rf = 0.7. B, effects of d-Ser and the analog on production of KDS. The SPT reaction was carried out using partially purified SPT as in A and [14C]-palmitoyl-CoA in the presence of the indicated amount of l-Ser or the analog. The production of KDS was detected by thin layer chromatography (upper panel) and quantified using a BAS2500 system (bottom panel).

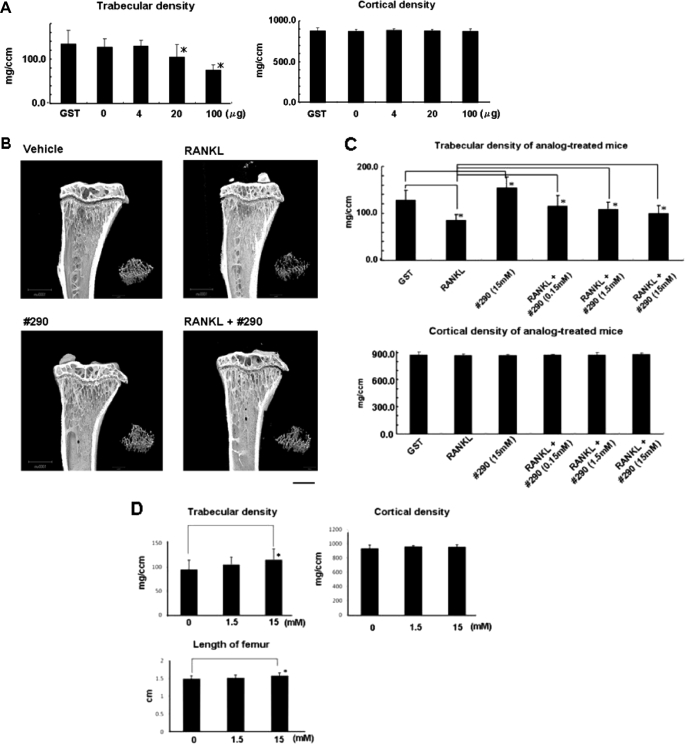

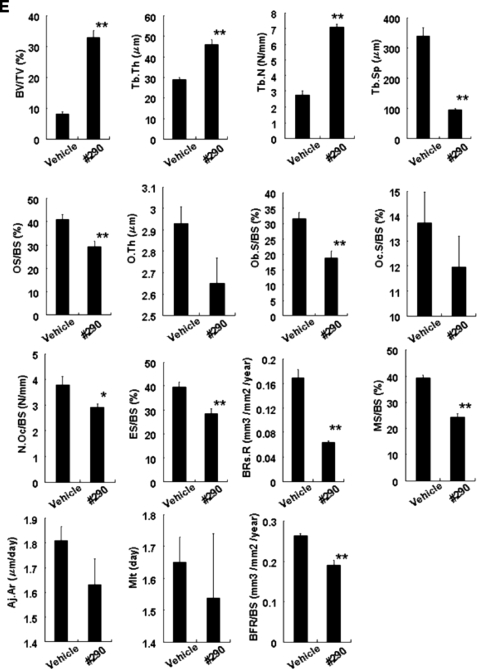

Effects of the Analog on Bone Structure and Turnover

Given the potential of the analog as an inhibitor of osteoclastogenesis in vitro, we wanted to examine its effect in vivo, aiming to answer two questions; does the analog actually suppress osteoclastogenesis in vivo, and does it regulate bone turnover? To this end, we first prepared mice whose bone turnover was enhanced by introducing recombinant RANKL via an intraperitoneal injection. This procedure was previously reported as useful for studying the consequences of high bone turnover for bone quality and strength in animals (10, 11). The administration of 100 μg of RANKL/day for 3 days in C57BL/6 mice was found to induce a loss of bone density in trabecular bone of tibiae as shown in Fig. 6 (A and B), when assessed using pQCT and micro-CT. The density in cortical bone, on the other hand, was unaffected under such conditions (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Effects of analog 290 on bone structure and histomorphometry. A, preparation of high bone turnover mice. The indicated amount of recombinant soluble RANKL was administered to C57BL/6 mice (n = 10) every day for 4 days. Trabecular and cortical densities of tibiae were measured using pQCT as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The bars represent the means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05. B, effects of RANKL treatment and dosage of analog 290 on bone structure: micro-CT analysis. Tibiae of mice treated with RANKL (100 μg) or/and analog 290 (15 mm) for 4 days were scanned by micro-CT and representative images are shown. Bar, 1,000 μm. C, effects of dosage of analog 290 on bone density in control and RANKL-administered mice. Indicated concentrations of the analog were injected intraperitoneally twice a day for 4 days into mice (n = 10) treated with either GST or 100 μg RANKL as in A, and bone density was measured. The bars represent the means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05. D, 90-day treatment with the analog. The analog was injected in C57BL/6 mice for 90 days, and the bone density of trabecular as well as cortical section of tibiae was measured as in C. E, histomorphometry analysis of tibiae metaphyses. C57BL/6 mice (n = 6) were treated with either vehicle or analog 290 (15 mm) for 4 weeks, and left tibiae were used for static and dynamic histomorphometric assay. BV/TV, bone volume/tissue volume; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Sp, trabecular separation; OS/BS, osteoid surface/bone surface; O.Th, osteoid thickness; Ob.S/BS, osteoblast surface/bone surface; Oc.S/BS, osteoclast surface/bone surface; N.Oc/BS, number of osteoclasts/bone surface; ES/BS, eroded surface/bone surface; BRs.R, bone resorption rate; MS/BS, mineralizes surface/bone surface; Aj.AR, adjusted apposition rate; Mlt, mineralization lag time; BFR/BS, bone formation rate/bone surface. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, respectively, versus vehicle-treated mice.

We then examined the effect of the analog dosage on bone turnover in terms of bone density using RANKL-treated as well as control (GST-treated) C57BL6 mice. The LD50 of the analog in C57BL6 mice was examined and determined as 2,845 mg/kg of body weight (data not shown). When 15 mm of the analog was administered to the control mice for 3 days, a significant increase in bone density was observed (Fig. 6C), suggesting an apparent effect on bone resorption. Bone architecture appeared normal as a whole, and yet no osteopetrotic status was observed in analog 290-treated mice (Fig. 6B). Subsequently, we tested its effect in RANKL-treated mice. When the analog was administered twice a day prior to the RANKL treatment and the following 3 days at three different concentrations, the loss of bone density in trabecular bone was significantly prevented (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, the administration of analog 290 for 3 months apparently had no significant effect on the condition of C57BL/6 mice such as body weight, whereas bone density remained high (Fig. 6D).

Furthermore, histomorphometry was performed on cancellous bones of vehicle- and analog 290-treated mice, and indices are shown in Fig. 6E. Parameters concerning osteoclasts and resorbing activity such as osteoclast surface/bone surface, number of osteoclasts/bone surface, eroded surface/bone surface, and bone resorption rate appeared to be suppressed as expected. Slight reductions in mineralization of surface/bone surface and bone formation rate/bone surface may reflect the decreased coupling and/or bone turnover. As a result, a significant increase in total bone volume/tissue volume as well as in trabecular structure (trabecular thickness, trabecular number, and trabecular separation) was noted as a whole.

DISCUSSION

Previous findings that l-Ser was required in the in vitro differentiation system and that the introduction of d-Ser suppressed the formation of osteoclasts suggested a novel method of regulating osteoclastogenesis and prompted us to search for serine analogs with more desirable properties. We consequently identified the analog 290, H-Ser(tBu)-OMe HCl, containing a l-Ser backbone and forming methyl ester but have been unable to identify the structural characteristics distinguishing analog 290 from the rest. Therefore, at this moment, we cannot make predictions based solely on structure. Analog 290 showed solubility in water and relatively strong inhibitory activity; it had not only an inhibitory effect on osteoclastogenesis in vitro but a significant and rapid suppressive effect on bone turnover in mice.

Another characteristic feature of the analog was that it showed a competitive effect with l-Ser on SPT that catalyzes the condensation of palmitoyl-CoA and l-Ser to produce KDS (20). d-Ser was reported to inhibit KDS production in a competitive manner (19). Incubation of SPT with [palmitoyl-14C]palmitoyl-CoA and the analog did not produce [14C]KDS. An analysis of the production of KDS from l-Ser using partially purified SPT and [14C]palmitoyl-CoA revealed the analog to be ∼50% as effective as d-Ser, suggesting that the analog has weaker activity than d-Ser as an inhibitor of SPT. Combined with the results obtained using the SPT inhibitor myriocin, these findings strongly suggest that the analog exerts its effect by down-regulating the production by SPT of the initial metabolite in the metabolism of l-Ser, and this may be the cause of the inhibitory effect on osteoclastogenesis. Hanada et al. (13) reported that all of the amino, carboxyl, and hydroxyl groups of l-Ser are responsible for the substrate's regulation of SPT. Because only the amino group is conserved intact in the analog, the weaker activity could be due to a lack of both carboxyl and hydroxyl groups at appropriate positions. However, detailed analyses may be required for understanding the functional mechanism of analog 290. Furthermore, d-Ser at 3 mm had a toxic effect on differentiating RAW264 cells but little effect on fibroblastic cells, suggesting a high turnover of serine metabolism to be a prerequisite for osteoclastogenesis.

We observed that the analog treatment caused the reduction of RANK expression and the relocalization of RANK from membrane lipid rafts. This may explain the down-regulation of MAPK activity and the expression level of c-Fos and NFAT2 in those cells. The expression of RANK was also significantly suppressed by 1.0 μm myriocin administration. Therefore, it seems that reduced levels of sphingolipid metabolites caused by the down-regulation of SPT activity by the analog resulted in the down-regulation of RANK expression and the modulation of its localization in membrane lipid rafts. Regarding this, glycosphingolipid was reported to play an important role in osteoclastogenesis (17, 21). d-threo-1-phenyl-2-decanoylamino-3-morpholino-1-propanol, a gycosylceramide synthase inhibitor, was shown to completely inhibit the formation of osteoclasts among bone marrow cells, and the addition of LacCer rescued the formation of TRAP-positive mononucleated cells but not multinucleated cells (17). Here the addition of LacCer to the analog-treated RAW264 cells rescued the suppressed formation of TRAP-positive MN cells accompanying an up-regulation of NFAT2 expression. Therefore, the recovery obtained with LacCer observed in this study may reflect either the difference in cell-type used or the partial inhibition of SPT by analog 290. In any case, how LacCer regulates RANK expression is an intriguing question and awaits further analysis.

The usefulness of the analog as a modulator of osteoclastogenesis was further tested in vivo. In fact, we observed the effect of the dosage of analog 290 in vivo using control and high bone turnover mice. Osteoporosis and rheumatoid arthritis are considered major diseases in the field of bone metabolism in terms of the number of patients affected as well as the severity of their effect on ordinary life. Various approaches and drugs have been used to treat these diseases. The l-Ser analog with the inhibitory activity of SPT thus identified may have unique potential as a therapeutic tool, given that it is completely different from currently available drugs in terms of its chemical as well as biological properties and has low production costs. Importantly, because l-Ser is considered a nonessential amino acid in mammals, and the methodology described below does not modify the l-Ser biosynthetic pathway at the genetic level, there should be little damage to homeostasis. Although treatment for 3 months did not cause any obvious change in mice, a more precise analysis may be needed if the analog is to be used for therapeutic purposes.

Footnotes

- MN

- multinucleated

- KDS

- 3-ketodihydrosphingosine

- SPT

- serine palmitoyltransferase

- LacCer

- lactosylceramide

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- TRAP

- tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Väänänen H. K., Laitala-Leinonen T. (2008) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 473, 132–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teitelbaum S. L. (2007) Am. J. Pathol. 170, 427–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle W. J., Simonet W. S., Lacey D. L. (2003) Nature 423, 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyce B. F., Xing L. (2008) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 473, 139–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishida N., Hayashi K., Hoshijima M., Ogawa T., Koga S., Miyatake Y., Kumegawa M., Kimura T., Takeya T. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 41147–41156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogawa T., Ishida-Kitagawa N., Tanaka A., Matsumoto T., Hirouchi T., Akimaru M., Tanihara M., Yogo K., Takeya T. (2006) J. Bone Miner. Metab. 24, 373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishida N., Hayashi K., Hattori A., Yogo K., Kimura T., Takeya T. (2006) J. Bone Miner. Res. 21, 48–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ha H., Kwak H. B., Lee S. K., Na D. S., Rudd C. E., Lee Z. H., Kim H. H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 18573–18580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akhila J., Deepa S., Alwar M. (2007) Curr. Sci. 93, 917–920 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lloyd S. A., Yuan Y. Y., Kostenuik P. J., Ominsky M. S., Lau A. G., Morony S., Stolina M., Asuncion F. J., Bateman T. A. (2008) Calcif. Tissue Int. 82, 361–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomimori Y., Mori K., Koide M., Nakamichi Y., Ninomiya T., Udagawa N., Yasuda H. (2009) J. Bone Miner. Res. 24, 1194–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parfitt A. M., Drezner M. K., Glorieux F. H., Kanis J. A., Malluche H., Meunier P. J., Ott S. M., Recker R. R. (1987) J. Bone Miner. Res. 2, 595–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanada K., Hara T., Nishijima M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 8409–8415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merrill A. H., Jr. (1983) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 754, 284–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams R. D., Wang E., Merrill A. H., Jr. (1984) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 228, 282–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka S., Nakamura K., Takahasi N., Suda T. (2005) Immunol. Rev. 208, 30–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwamoto T., Fukumoto S., Kanaoka K., Sakai E., Shibata M., Fukumoto E., Inokuchi J., Takamiya K., Furukawa K., Kato Y., Mizuno A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 46031–46038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanada K., Hara T., Fukasawa M., Yamaji A., Umeda M., Nishijima M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 33787–33794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanada K., Hara T., Nishijima M. (2000) FEBS Lett. 474, 63–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanada K. (2003) Biochim. Bipphys. Acta 1632, 16–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitatani K., Idkowiak-Baldys J., Hannun Y. A. (2008) Cell Signal. 20, 1010–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]