Abstract

MecA is an adaptor protein that regulates the assembly and activity of the ATP-dependent ClpCP protease in Bacillus subtilis. MecA contains two domains. Although the amino-terminal domain of MecA recruits substrate proteins such as ComK and ComS, the carboxyl-terminal domain (residues 121–218) has dual roles in the regulation and function of ClpCP protease. MecA-(121–218) facilitates the assembly of ClpCP oligomer, which is required for the protease activity of ClpCP. This domain was identified to be a non-recycling degradation tag that targets heterologous fusion proteins to the ClpCP protease for degradation. To elucidate the mechanism of MecA, we determined the crystal structure of MecA-(121–218) at 2.2 Å resolution, which reveals a previously uncharacterized α/β fold. Structure-guided mutagenesis allows identification of surface residues that are essential for the function of MecA. We also solved the structure of a carboxyl-terminal domain of YpbH, a paralogue of MecA in B. subtilis, at 2.4 Å resolution. Despite low sequence identity, the two structures share essentially the same fold. The presence of MecA homologues in other bacterial species suggests conservation of a large family of unique degradation tags.

Introduction

Proteolysis regulated by the AAA+ superfamily is important to both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. It is an important regulatory mechanism to biological processes such as stress responses or protein quality control under non-stress conditions (1). In prokaryotic cells, ClpP and its associated adaptor ATPases form distinct proteolytic complexes with an architecture that is similar to the eukaryotic 26 S proteasome. The closely related ATPases include ClpA, ClpB, ClpC, ClpE, ClpL, ClpV, ClpX, and HslU (ClpY) (2). The active, hexameric ATPases unfold and translocate the substrate proteins to the proteolytic chamber within the double ring of ClpP heptamers for degradation (3). Among these ATPases, ClpC is particularly intriguing because it requires an adaptor protein to stimulate its ATPase activity and to facilitate its oligomerization and activation. In Bacillus subtilis, MecA or its paralogue YpbH is required for assembly of the active protease complex ClpCP and recruitment of substrate proteins such as ComK and ComS (4–9).

MecA contains two domains, the N-terminal domain and the C-terminal domain, which are connected by a flexible linker sequence. The N-terminal domain of MecA is essential for substrate recognition, whereas the C-terminal domain was reported to mediate the interaction with ClpC and to stimulate the ATPase activity of ClpC (9, 10). In the accompanying article (23), we identified MecA-(121–218) to be a structure entity that plays dual roles. On one hand, MecA-(121–218) is the minimal domain that by itself is sufficient to induce ClpC oligomerization, to stimulate the ATPase activity of ClpC, and to facilitate the assembly and activation of the ClpCP complex. On the other hand, we demonstrated that MecA-(121–218) is a non-recycling degradation tag that targets heterologous fusion proteins for degradation by the ClpCP protease. As indicated by the term non-recycling, MecA-(121–218) is also degraded together with the substrate fusion protein. The association and degradation of MecA-(121–218) result in dynamic cycles of assembly and disassembly of the ClpCP complex. We also showed that the C-terminal domain of YpbH (residues 101–194), which share a sequence identity of 31% and sequence similarity of 63% with MecA-(121–218), functions similarly as MecA-(121–218), both for assembly of the ClpCP protease and as a non-recycling degradation tag.

The biochemical observations raised the following questions. First, how does the structure of MecA-(121–218) support its function? Second, given the moderate sequence identity and similarity between MecA-(121–218) and YpbH-(101–194), do they have a similar structure? Third and more importantly, does the prokaryotic degradation tag, MecA-(121–218), exhibit any structural similarity to the eukaryotic degradation tag ubiquitin?

To address these questions, we crystallized and determined the structures of MecA-(121–218) and YpbH-(101–194) at 2.2 and 2.4 Å resolution, respectively. The two structures share essentially the same fold, a previously uncharacterized α/β fold. We also performed structure-guided mutagenesis for MecA and identified surface residues that may mediate ClpC binding and ComK degradation. The structural study, together with the biochemical observations reported in the accompanying article (23), provides important insights into the mechanistic understanding of MecA-regulated assembly and activation of the ClpCP protease.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Preparation

All clones were generated using a standard PCR-based cloning strategy, and the identities of individual clones were verified through double-strand plasmid sequencing. ClpC, MecA, and YpbH variants were subcloned into pGEX-6P-1 vector (GE Healthcare) with an N-terminal glutathione S-transferase tag or PKTG vector with a C-terminal glutathione S-transferase tag and overexpressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) at 22 °C. The soluble fraction of the E. coli lysate was purified through a glutathione-Sepharose column and cleaved by the PreScissionTM protease (GE Healthcare) wherever necessary. ClpP was overexpressed in E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) as a C-terminal His6-tagged protein using the pET-21b vector (Novagen). The soluble fraction of ClpP-His6 in the E. coli lysate was purified with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (Qiagen). ComK was overexpressed in E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) in a PLM303 vector (a derivative of pET-27a). The soluble fraction of maltose-binding protein fusion ComK in the E. coli extracts was purified over amylose resin (New England Biolabs) and then cleaved by the PreScission protease (GE Healthcare). After affinity purification, all proteins were further purified by anion-exchange chromatography (Source 15Q, GE Healthcare) and gel filtration chromatography (Superdex 200, GE Healthcare). Protein concentration was determined by UV spectroscopic measurement at 280 nm.

ClpCP Degradation Assay

In vitro degradation assays were reconstituted as described previously (7, 8). ClpC and ClpP were added at 4 μm final concentration. All MecA variants and ComK were added at 6 μm final concentration. All protein concentrations reported in this study refer to those of the monomers, regardless of the oligomerization states of the proteins.

Interaction Assay by Gel Filtration

Size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200, 10/30, GE Healthcare) was employed to examine potential protein-protein interaction. In all cases, proteins were incubated at 4 °C for at least 45 min to allow equilibration. The assay buffer contained 10 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, and 2 mm dithiothreitol. The eluted fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining.

Crystallization of MecA-(121–218) and YpbH-(101–194)

Crystals were grown using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method. Crystals of MecA-(121–218) were grown at 18 °C by mixing an equal volume of the protein (10 mg/ml) with reservoir solution containing 14% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 3350, 300 mm CaCl2, 4% ethylene glycol, and 0.1 m Bis-Tris,4 pH 6.2. Crystals of YpbH-(101–194) were grown at 18 °C by mixing an equal volume of the protein (10 mg/ml) with reservoir solution containing 1.85 m (NH4)2SO4, 2% polyethylene glycol 400, and 100 mm HEPES at pH 7.5.

Structure Determination

MecA crystals were soaked into 200 mm NaI for 30 s and flash-frozen in the cold nitrogen stream. Single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) data were measured on a Rigaku FR-E system. All diffraction data were integrated and scaled using DENZO and SCALEPACK (11). Further processing was carried out using programs from the CCP4 package (12). Full data collection and processing statistics are shown in Table 1. The heavy atom positions in the iodine-soaked mutant crystal were determined using SHELXD (13). Heavy atom parameters were then refined, and initial phases were generated in the program PHASER (14) with the SAD experimental phasing module. Density modification, including solvent flattening and histogram matching, was performed using DM (15). The initial model was built with BUCCANEER (16). Additional missing residues in the auto-built model were added in COOT (17) manually. The structure was refined with PHENIX (18).

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

I-SAD, iodine-based; MR, molecular replacement.

| Proteina |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| MecA 121–218 | YpbH 104–194 | YpbH 101–194 | |

| Data collection | |||

| X-ray source | Rigaku FR-E | Rigaku MM-007HF | BL41XU, SPring-8 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.5418 | 1.5418 | 1.0000 |

| Space group | C2221 | P21 | I4122 |

| Unit cell (Å) | a = 69.52, b = 107.27, c = 109.61 | a = 28.93, b = 71.66, c = 39.33, β = 95.35 | a = 162.06, c = 142.85 |

| Number of molecules in ASU | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Resolution (outer shell) (Å) | 2.17 (2.25-2.17) | 2.09 (2.21-2.09) | 2.4 (2.49-2.4) |

| Rmergeb (outer shell) (%) | 6.9 (43.1) | 7.9 (73.2) | 8.4 (78.2) |

| I/σ (outer shell) | 36.75 (4.55) | 9.09 (2.6) | 25.3 (3.0) |

| Completeness (outer shell) (%) | 99.4 (98.7) | 94.1 (88) | 99.7 (100) |

| Redundancy (outer shell) | 8.5 (7.9) | 2.9 (2.7) | 8.1 (8.3) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 50.3 | 37.7 | 54.0 |

| Phasing protocol | I-SAD | I-SAD | MR |

| Refinement | |||

| R/Rfreec (%) | 22.2/27.9 | 21.8/30.4 | 23.0/27.0 |

| Number of atoms/B-factor: | |||

| Protein | 3063/51.3 | 1422/43.1 | 4332/50.0 |

| Water | 86/52.9 | 60/45.8 | 153/45.8 |

| Iodine | 35/69.1 | 14/62.0 | |

| All | 3184/51.5 | 1496/43.4 | 4485/49.8 |

| Ramachandran plot | |||

| Most favored (%) | 86.6 | 91.0 | 89.1 |

| Additional allowed (%) | 11.4 | 9.0 | 10.9 |

| Generously allowed (%) | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Disallowed (%) | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| r.m.s.d. | |||

| Bond distances (Å) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.007 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.31 | 1.16 | 1.161 |

| Omega values (°) | 1.103 | 0.858 | 1.034 |

aValues in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

bRmerge = ΣhΣi|Ih,i − Ih|/ΣhΣiIh,i, where Ih is the mean intensity of the i observations of symmetry related reflections of h.

c R = Σ|Fobs − Fcalc|/ΣFobs, where Fcalc is the calculated protein structure factor from the atomic model. Rfree was calculated with 5% of the reflections selected randomly.

YpbH-(104–194) crystals were soaked into 500 mm NaI for 60 s and flash-frozen in the cold nitrogen stream. SAD data were measured at a Rigaku MicroMax-007HF system and processed with the XDS package (14). YpbH-(101–194) native data were collected at the SPring-8 beamline BL41XU at the wavelength of 1.0 Å using MX-225 CCD detector, integrated, and scaled using DENZO and SCALEPACK (11). Full data collection and processing statistics are shown in Table 1. The iodine sites in the YpbH-(104–194) crystal were determined using SHELXD (13). Heavy atom parameters were then refined, and initial phases were generated in the program PHASER (14). The real-space constraints, including solvent flattening, histogram matching, and non-crystallographic symmetry averaging, were applied using DM (15). The initial model was built with BUCCANEER (16). Additional missing residues in the auto-built model were added in COOT (17) manually. The YpbH-(104–194) model was used for molecular replacement with the program PHASER (17) into the YpbH-(101–194) crystal form. The YpbH-(101–194) structure was refined with PHENIX (18).

RESULTS

Structure of MecA-(121–218)

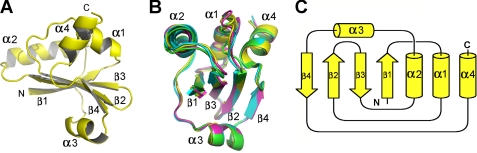

To decipher the mechanism by which MecA-(121–218) functions, we crystallized this domain and determined its three-dimensional structure at 2.2 Å resolution using iodine-based SAD (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The final atomic model of MecA-(121–218) contains amino acids 127–218, with the N-terminal 6 residues disordered. The compact structure comprises a central β-sheet of four antiparallel β-strands, which is surrounded by three α-helices (α1, α2, and α4) on one side and a single α-helix (α3) on the other side (Fig. 1A). There are four molecules of MecA-(121–218) in each asymmetric unit; these four molecules exhibit identical structure and can be very well superimposed with one another (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Structure of the carboxyl-terminal domain of MecA (residues 121–218). A, overall structure of MecA-(121–218). The structure contains four α-helices and four antiparallel β-strands, which form a central β-sheet surrounded by α-helices. B, the four molecules of MecA-(121–218) in one asymmetric unit are structurally identical. C, the topology diagram of MecA-(121–218).

Exhaustive search of the Protein Data Bank (PDB) using the program DALI (19) did not identify any continuous polypeptide or isolated domain that exhibits a similar fold as MecA-(121–218) (Fig. 1C). However, the search identified a large number of structures that display partial similarity to MecA-(121–218). The entry with the highest Z-score (a measure of structural similarity) of 5.3 is the structure of the protein alkyl-dihydroxyacetone phosphate synthase (20), of which a discontinuous portion can be aligned with MecA-(121–218) with a root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) of 2.9 Å for 78 aligned Cα atoms (Fig. 2, A and B). The second closest entry, with a Z-score of 5.2, is the structure of a small, hypothetical protein from Thermotoga maritima (PDB code 2NZC) (Fig. 2, A and C). We conclude that MecA-(121–218) represents a previously uncharacterized fold (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 2.

Structure of MecA-(121–218) defines a previously uncharacterized fold. A, a ribbon diagram of MecA-(121–218). B, a portion (colored red) of the structure of alkyl-dihydroxyacetone phosphate synthase (PDB code 2UUV) shows limited homology with that of MecA-(121–218). C, structure of a hypothetical protein from T. maritima (PDB code 2NZC, colored blue) shows limited homology with that of MecA-(121–218).

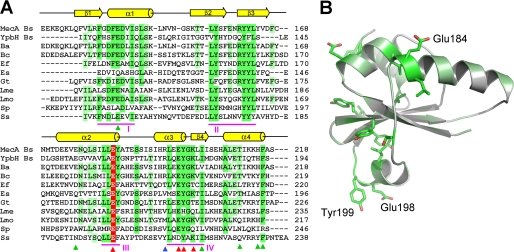

Given the sequence conservation of the C-terminal domain of MecA in other bacterial species (Fig. 3A), we propose that, in analogy to MecA, these proteins use their C-terminal domain as a degradation tag. We further posit that each of these proteins may facilitate assembly of the ClpCP protease in its cognate bacterial species.

FIGURE 3.

Sequence alignment identifies conserved regions in MecA. A, sequence alignment of MecA with 10 other homologous proteins. Conserved amino acids are colored green and light green. Red, blue, and green arrows denote those residues whose mutations result in loss, partial loss, and no loss of MecA degradation, respectively. YpbH (accession code: GenBankTM CAB14213) is also from B. subtilis. The other MecA homologues are from: Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (Ba, ABS73516), Bacillus coahuilensis (Bc, ABFU01000021), Geobacillus thermodenitrificans (Gt, ABO66079), Enterococcus faecalis (Ef, AAO82382), Exiguobacterium sibiricum (Es, ACB61267), Leuconostoc mesenteroides (Lme, ABJ62794), Listeria monocytogenes (Lmo, CAD00268), Streptococcus pneumoniae (Sp, ACH47966), and Staphylococcus saprophyticus (Ss, BAE18932). B, highly conserved amino acids map to one side of the MecA-(121–218) structure. The three labeled amino acids, Glu-184, Glu-198, and Tyr-199, are likely to play a key role in binding to ClpC. Mutation of these amino acids led to weakened interaction with ClpC and subsequent loss of functions.

Functional Characterization of the MecA Fold

The advent of structural information on MecA-(121–218) greatly facilitated understanding of its function. Sequence alignment of 11 MecA homologues revealed four patches (I, II, III, and IV) of highly conserved amino acids (Fig. 3). Patch II contains mostly hydrophobic amino acids on strands β2 and β3, which likely contribute to the structural stability of the MecA fold. The other three patches are exposed on the surface and may play an important role in MecA function.

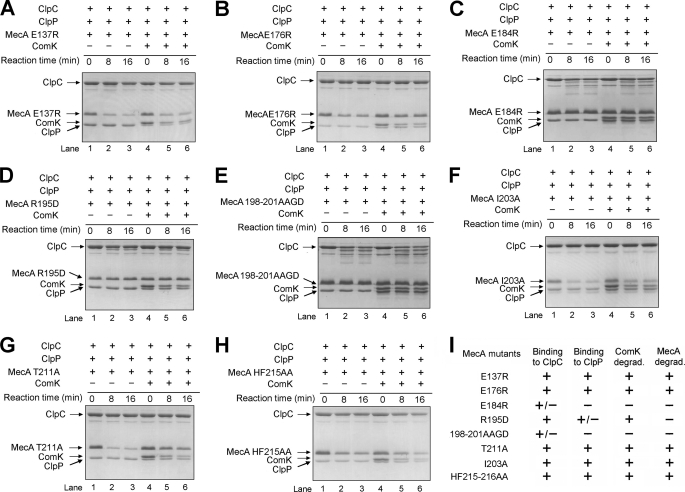

To understand the biochemical function of these conserved residues, we generated eight full-length, mutant MecA proteins. For six of the eight mutant proteins, there is only a single point mutation in each protein. The other two each contains more than one point mutation. We purified these eight mutant proteins to homogeneity and evaluated their abilities to interact with ClpC and to mediate ClpCP degradation of themselves and ComK (Fig. 4, A–H). The same assays were performed for the wild-type MecA and are reported in the accompanying article (23). When compared with the wild-type protein, five mutations, E137R in patch I, E176R in patch III, I203A in patch IV, and T211A and H215A,F216A, had little or no impact on ClpCP degradation of the cognate MecA mutant and ComK (Fig. 4, A, B, F, G, and H). Subsequent characterization demonstrated that these mutant proteins retained the ability to oligomerize ClpC and to interact with the ClpCP protease (Fig. 4I). Two mutations, E184R in patch III and E198A,Y199A,K201D in patch IV, led to complete abrogation of ClpCP degradation of the associated MecA mutant and ComK (Fig. 4, C and E). Although still interacting with ClpC, these two mutations abolished the ability to mediate formation of a stable ClpC hexamer (data not shown), thus disrupting assembly of a functional ClpCP complex. Interestingly, the missense mutation R195D eliminated degradation of MecA itself but only weakened degradation of ComK (Fig. 4D). MecA R195D retained interaction with ClpC and weak interaction with the ClpCP protease.

FIGURE 4.

Functional characterization of surface residues in the degradation tag MecA-(121–218). The mutations are E137R (A), E176R (B), E184R (C), R195D (D), E198A,Y199A,K201D (E), I203A (F), T211A (G), and H215A,F216A (H). I, a summary of the functional characterization of surface residues in MecA-(121–218).

These results identified two regions of the MecA surface that are important for its function: one around Glu-184 in patch III and the other around the sequence EYGK in patch IV. These two regions are located on the opposite sides of the MecA fold (Fig. 3B), yet mutations in either region led to compromised ability of MecA to interact with ClpC, suggesting direct involvement of both regions in binding to ClpC.

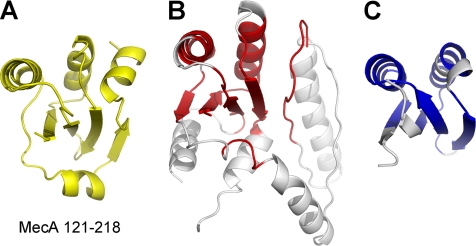

Structure of YpbH-(101–194)

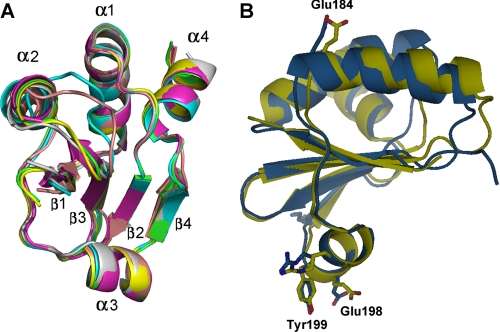

YpbH is a paralogue of MecA. It targets different substrate proteins such as Spx, but not ComK or ComS, to ClpCP for degradation (6). Similar to MecA-(121–218), YpbH-(101–194) is able to target the BIR1 domain (residues 31–145) of DIAP1 (21) for degradation as a heterologous fusion protein (supplemental Fig. 1). YpbH-(101–194) and MecA-(121–218) share sequence identity of 31% and sequence similarity of 63%. To examine whether YpbH-(101–194) is structurally similar to MecA-(121–218), we crystallized the C-terminal fragment of YpbH (residues 101–194) and determined its structure at 2.4 Å resolution. Due to the relatively moderate sequence similarity between MecA and YpbH, molecular replacement using MecA-(121–218) as the starting model did not result in an apparent solution. We had to solve the phase problem using the iodine-SAD data collected on crystals of YpbH residues 104–194. Upon completion of the structural refinement, it became obvious that YpbH-(101–194) shares the same fold as MecA-(121–218). There are six molecules of YpbH-(101–194) in each asymmetric unit. The structures of the six molecules are almost identical (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

YpbH-(101–194) and MecA-(121–218) share an identical structural fold. A, the six molecules of YpbH-(101–194) in one asymmetric unit are superimposed with each other. They are structurally identical. B, YpbH-(101–194) can be superimposed to MecA-(121–218) with an r.m.s.d. of 1.16 Å over 75 aligned Cα atoms. YpbH and MecA are displayed in blue and yellow, respectively. Key residues identified in MecA-(121–218) are highlighted in both molecules.

Despite the moderate sequence similarity, YpbH-(101–194) can be closely superimposed with MecA-(121–218), with an r.m.s.d. of 1.16 Å over 75 aligned Cα atoms. The only apparent differences exist in some of the surface loop regions. The positions of the conserved amino acids are very similar in both structures. In particular, all of the crucial residues identified in MecA-(121–218) are located at nearly identical positions in YpbH-(101–194) (Fig. 5B). The structural conservation further suggests the important role of these residues.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we reported the crystal structures of MecA-(121–218) and YpbH-(101–194). Despite the moderate sequence similarity, the two structures share an almost identical, previously uncharacterized α/β fold. The distinct α/β fold of MecA-(121–218) is reminiscent of ubiquitin (22), but close examination revealed little structural similarity between these two degradation tags. BLAST search of the non-redundant protein data base resulted in more than 100 entries, mostly from Gram-positive bacteria, that share significant sequence similarity with MecA-(121–218), suggesting the existence of a large family of unique degradation tags with this novel fold.

Preliminary biochemical characterization suggests the involvement of two separate surface regions that are located on opposing sides of the MecA C-terminal domain. It is possible that each MecA molecule may interact with two neighboring ClpC molecules through distinct interfaces, hence strengthening the interactions between neighboring ClpC molecules. Another possibility is that MecA binding to ClpC causes a conformational change in ClpC that allows oligomerization.

The structural study reported in this study and biochemical characterizations reported in the accompanying article (23) allow us to propose a working model of the MecA-ClpCP system, as discussed in the accompanying article. Despite these tantalizing clues, many important questions remain to be answered. At present, it is mechanistically unknown how MecA facilitates the oligomerization of ClpC and the assembly of ClpCP complex or how MecA binds and delivers the substrate protein to the ClpCP protease. The structure of a MecA-ClpC complex should provide critical insights into these processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Shimizu, T. Kumasaka, and S. Baba at the SPring-8 beamline BL41XU for on-site assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology (Grant 2009CB918801), Tsinghua University 985 Phase II funds, Project 30888001 supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and Beijing Municipal Commissions of Education and Science and Technology.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3JTP, 3JTO, and 3JTN) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- Bis-Tris

- 2-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino-2-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-propanediol

- SAD

- single-wavelength anomalous dispersion

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prepiak P., Dubnau D. (2007) Mol. Cell 26, 639–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zolkiewski M. (2006) Mol. Microbiol. 61, 1094–1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sauer R. T., Bolon D. N., Burton B. M., Burton R. E., Flynn J. M., Grant R. A., Hersch G. L., Joshi S. A., Kenniston J. A., Levchenko I., Neher S. B., Oakes E. S., Siddiqui S. M., Wah D. A., Baker T. A. (2004) Cell 119, 9–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlothauer T., Mogk A., Dougan D. A., Bukau B., Turgay K. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2306–2311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Persuh M., Mandic-Mulec I., Dubnau D. (2002) J. Bacteriol. 184, 2310–2313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakano S., Zheng G., Nakano M. M., Zuber P. (2002) J. Bacteriol. 184, 3664–3670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turgay K., Hamoen L. W., Venema G., Dubnau D. (1997) Genes Dev. 11, 119–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turgay K., Hahn J., Burghoorn J., Dubnau D. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 6730–6738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirstein J., Schlothauer T., Dougan D. A., Lilie H., Tischendorf G., Mogk A., Bukau B., Turgay K. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 1481–1491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Persuh M., Turgay K., Mandic-Mulec I., Dubnau D. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 33, 886–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods in Enzymology: Macromolecular Crystallography, part ACarter C. W., Jr., Sweet R. M. eds. Vol. 276, pp. 307– 326, Academic Press, New York: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collaborative Computational Project, Number Four ( 1994) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760– 76315299374 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider T. R., Sheldrick G. M. (2002) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1772–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2005) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 61, 458–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cowtan K., Main P. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 547, 487–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cowtan K. (2006) Acta Crystallogr. D. 62, 1002–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L. W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Terwilliger T. C. (2002) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holm L., Sander C. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 233, 123–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Razeto A., Mattiroli F., Carpanelli E., Aliverti A., Pandini V., Coda A., Mattevi A. (2007) Structure 15, 683–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan N., Wu J. W., Chai J., Li W., Shi Y. (2004) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 420–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vijay-Kumar S., Bugg C. E., Wilkinson K. D., Cook W. J. (1985) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 3582–3585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mei Z., Wang F., Qi Y., Zhou Z., Hu Q., Li H., Wu J., Shi Y. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 34366–34375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.