Abstract

TRPC5 forms non-selective cation channels. Here we studied the role of internal Ca2+ in the activation of murine TRPC5 heterologously expressed in human embryonic kidney cells. Cell dialysis with various Ca2+ concentrations (Ca2+i) revealed a dose-dependent activation of TRPC5 channels by internal Ca2+ with EC50 of 635.1 and 358.2 nm at negative and positive membrane potentials, respectively. Stepwise increases of Ca2+i induced by photolysis of caged Ca2+ showed that the Ca2+ activation of TRPC5 channels follows a rapid exponential time course with a time constant of 8.6 ± 0.2 ms at Ca2+i below 10 μm, suggesting that the action of internal Ca2+ is a primary mechanism in the activation of TRPC5 channels. A second slow activation phase with a time to peak of 1.4 ± 0.1 s was also observed at Ca2+i above 10 μm. In support of a Ca2+-activation mechanism, the thapsigargin-induced release of Ca2+ from internal stores activated TRPC5 channels transiently, and the subsequent Ca2+ entry produced a sustained TRPC5 activation, which in turn supported a long-lasting membrane depolarization. By co-expressing STIM1 plus ORAI1 or the α1C and β2 subunits of L-type Ca2+ channels, we found that Ca2+ entry through either calcium-release-activated-calcium or voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels is sufficient for TRPC5 channel activation. The Ca2+ entry activated TRPC5 channels under buffering of internal Ca2+ with EGTA but not with BAPTA. Our data support the hypothesis that TRPC5 forms Ca2+-activated cation channels that are functionally coupled to Ca2+-selective ion channels through local Ca2+ increases beneath the plasma membrane.

Introduction

The transient receptor potential (TRP)2 channel proteins comprise six transmembrane domains and multimerize to form ion channel complexes. Among the known families of ion channels, TRPs are unique in displaying an impressive diversity of cation selectivities, activation mechanisms, and functions (1). Specifically, members of the “canonical” TRP (TRPC) subfamily are non-selective cation channels that cause eventually Ca2+ entry and collapse of the cell membrane potential (2). TRPCs are readily activated after stimulation of receptor-tyrosine kinases or G-protein-coupled receptors that activate the phospholipase C signaling pathway (3). It is believed that diacylglycerol, a product of the phospholipase C signaling pathway, activates ion channels formed by TRPC3, TRPC6, and TRPC7 (4), although the activation mechanisms of TRPC1, TRPC4, and TRPC5 appear to be more complex (5, 6).

TRPC5 is enriched in the brain, where it is believed to control neurite extension and growth cone morphology (7, 8). TRPC5-deficient mice exhibit diminished innate fear levels, suggesting an essential role for TRPC5 in the function of the amygdala (9). Furthermore, TRPC5 has been implicated in endothelial and mast cell function as well as in rheumatoid arthritis (2). In growth cones TRPC5 forms homomeric channels, but it forms heteromultimers with TRPC1 to build TRPC1/TRPC5 ion channels in the soma of neurones (8). Numerous stimuli are apparently able to control the activity of TRPC5 channels. By interacting with extracellularly located binding sites, thioredoxin, protons, and lanthanides enhance TRPC5 channel currents (10–13). Acting intracellularly, nitric oxide enhances TRPC5 channel currents as well (14). Lysophospholipids and hypoosmotic- and pressure-induced membrane stretch act also as activators of TRPC5 channels (15, 16). Under some circumstances, the externalization of TRPC5 contributes substantially to the overall enhancement of TRPC5 channel currents (17, 18). All in all, TRPC5 are apparently target molecules of both extracellular and intracellular signals (5). As for other TRPC channels (e.g. Ref. 19), however, a central question is whether TRPC5 participates in store-operated Ca2+ entry. Previous studies have shown that maneuvers that activate store-operated Ca2+ entry also activate TRPC5 channels (20, 21). In mast cells the Ca2+ entry is apparently dependent on the presence of TRPC5 as well as on STIM1 and ORAI1, the key components of store-operated Ca2+ entry (22). Our understanding of the role of TRPC5 in store-operated Ca2+ entry was advanced by the finding that STIM1 binds to TRPC5 and is obligatory for TRPC5 channel activation via membrane receptor stimulation (23). Thus, it is likely that TRPC5 is part of the protein complex responsible for store-operated Ca2+ entry. However, it has been recently reported that knockdown of STIM1 does not reduce the agonist-induced activation of TRPC5 channels (24). Certainly, TRPC5 does not form store-operated ion channels in the classical sense (13, 25, 26). In contrast to store-operated ion channels, the activation of TRPC5 channels via receptor stimulation is abolished in the absence of internal Ca2+, and moderate increases of the internal Ca2+ concentration (Ca2+i) enhance TRPC5 channel currents (13, 20, 26–29). Disruption of the binding site for calmodulin and IP3 receptors in TRPC5 makes TRPC5 channels irresponsive to receptor stimulation (28, 30). Furthermore, internal Ca2+ potentiates agonist-activated TRPC5 channels in a voltage-dependent manner, suggesting an important role for internal Ca2+ in the activation of TRPC5 channels (27). As for all other putative modulators of TRPC5 channels, however, it is not known whether increases of internal Ca2+ are sufficient and necessary to activate TRPC5 channels.

Using a TRPC5 cell line as a model for homomeric TRPC5 channels, here we show that submicromolar Ca2+i suffices to enhance TRPC5 channels currents in a dose-dependent manner. Using photolysis of caged Ca2+, we demonstrate that stepwise Ca2+i increases activate TRPC5 channels in a millisecond time scale, i.e. long before the propagation of intracellular signaling cascades. Taking advantage of the fact that the opening of a non-selective cation channels depolarizes the cell membrane, we use membrane potential imaging to study the activation of TRPC5 in non-voltage-clamped cells and found that TRPC5 channels are transiently activated by the Ca2+ release from internal stores, whereas Ca2+ entry supports a sustained activation of TRPC5 channels. In co-expression experiments with calcium-release-activated-calcium (CRAC) and L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, we found that the local rise of internal Ca2+ induced by the opening of these Ca2+-selective ion channels is sufficient to activate TRPC5 channels, suggesting that TRPC5 channels represent Ca2+-activated channels functionally coupled to Ca2+-selective channels.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids, Transfection, and Cell Culture

The murine TRPC5, STIM1, and ORAI1 were cloned from brain and subcloned in a bicistronic expression vector, which contains the cDNA of the green fluorescence protein as expression marker (21, 31). To obtain a mutation in the murine ORAI1 that resembles the Scid mutation in human ORAI1 (32), the arginine at position 91 was replaced by tryptophan using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The HEK 293 cell line stably expressing the murine TRPC was cultured as previously described (28). Plasmids containing the murine TRPC5, STIM1, and ORAI1 were transfected into HEK 293 cells either individually or in combination using the AMAXA Nucleofector electroporation system (AMAXA Biosystems, Cologne, Germany). Similarly, the TRPC5 cell line was transfected with STIM1 alone or with STIM1 plus either ORAI1 or the modified ORAI1 carrying the Scid mutation (ORAI1 Scid). The STIM1 plasmid was mixed with one of the plasmids containing ORAI, ORAI1 Scid, or TRPC5 at a ratio of 1:2. STIM1 plus ORAI1 and TRPC5 were transfected at a ratio of 1:2:1. Additionally, the murine α1C and β2 subunits of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels were transfected in HEK cells and in the TRPC5 cell line at a ratio of 1:1 to express voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ channels. Experiments were performed on green fluorescence protein expressing cells 1–2 days after transfection.

Whole-cell Current Recordings

Ion currents were recorded in the tight-seal whole-cell configuration at room temperature using an EPC-9 amplifier (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany) with a sampling rate of 20 kHz. Voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV (duration 50 ms) were delivered every 2 s to record in experiments with TRPC5 and CRAC channels. The holding potential was 0 mV. Capacitive currents were determined and corrected in advance of each ramp. Current densities were calculated using the initial Cslow value. The time courses of ion currents were monitored using current densities measured at +80 and −80 mV. In experiments with voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, voltage steps to 0 mV (100 ms) and +80 mV (50 ms) were delivered every 2 s from a holding potential of −60 mV, and ion current time courses were monitored at 0 and +80 mV. The standard pipette solution contained 120 mm CsCl, 10 mm NaCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 10 mm EGTA, and 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.2 (CsOH). The free Ca2+ concentration (Ca2+i) was adjusted by adding appropriate amounts of CaCl2 calculated using Webmaxc Standard. In the experiments in which the sensitivity to internal Ca2+ was determined, we used a nominally Ca2+ free (NCaF) bath solution which was as follows: 120 mm NaCl, 10 mm CsCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 10 mm Hepes, 10 mm glucose, pH 7.2 (NaOH). To record CRAC currents, 5 mm CaCl2 was added to NCaF. The osmolarity of external and internal solutions was 290–310 mosm.

Photolysis of Caged Ca2+ and Measurements of Internal Ca2+

Cells were clamped at −70 mV using an EPC-9 amplifier (HEKA), and ion currents were continuously sampled at 10 kHz. The pipette solution contained 120 mm CsCl, 10 mm NaCl, 10 mm Hepes, 0.4 mm MgCl2, 5.6 mm nitrophenyl-EGTA, 0.2 mm FURA-2, 0.3 mm Furaptra, 2.185 mm CaCl2, pH 7.3 (CsOH). The extracellular solution contained 130 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm Hepes, 30 mm glucose, pH 7.3 (NaOH). For ratiometric measurements of Ca2+i, a mixture of the indicator dyes FURA-2 and Furaptra (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was excited at 340/380 nm with a monochromator (Polychrome IV, TILL Photonics, Gräfelfing, Germany), as previously described (33). Whole-cell recordings with test solutions of defined Ca2+i were used for in vivo calibration of the ratiometric Ca2+ signals. Nitrophenyl-EGTA (supplied by G. Ellis-Davis, MCP Hahnemann University, Philadelphia, PA) was photolysed by a flash of ultraviolet light (xenon flash lamp, Rapp OptoElectronics, Hamburg, Germany) focused through a Zeiss objective (×40, Fluar, 1.3) of an inverted microscope (Axiovert 200, Zeiss, Germany).

Membrane Potential and Calcium Imaging

The FLIPR membrane potential (FMP) dye was used to image changes of the membrane potential. FMP is a no-wash, single-wavelength fluorescent dye of proprietary composition that was originally developed for high-throughput screening (34). In the present study we used FMP in a single cell imaging system that comprises the microscope iMIC and the monochromator Polychrome V (TILL Photonics). Following the instructions of the manufacturers, FMP and additional quenchers were dissolved in a Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) supplemented with Hepes (FLIPR Membrane Potential Assay kit BLUE; Molecular Devices). HBSS contained 1.3 mm CaCl2, 5.4 mm KCl, 136.9 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm MgCl2, 0.4 mm KH2PO4, 0.4 mm MgSO4, 0.3 mm Na2HPO4, 5.5 mm glucose, and 20 mm Hepes, pH 7.4. The external Ca2+ concentration (Ca2+o) was varied between 1.25 and 5 mm by adding the appropriated amount of CaCl2 to a solution that contained 140 mm NaCl, 5.4 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 10 mm Hepes, 5 mm glucose, pH 7.2 (NaOH). The 0 Ca2+o solution contained 0.5 mm EGTA; the cells were incubated in FMP-containing HBSS for 15 min at room temperature before recordings. We used a single wavelength set to 530 nm for the excitation of FMP and collected the emitted fluorescence with a filter centered around 605 nm (emitter, ET 605/70m; dicroic, 565 DCXR; AHF Analysetechnik, Tübingen, Germany). To generate time courses, images containing 10–65 cells/frame were sampled every 2 s. Relative changes of the FMP fluorescence intensity are given as ΔF/F0, where F0 represents the background-subtracted, basal fluorescence intensity, and ΔF denotes the fluorescence intensity change with respect to F0.

The ratiometric fluorescent dye FURA-2 was used for Ca2+ imaging. As previously described (35), FURA-2 signals were monitored by exciting alternately at 340 and 380 nm and measuring the emitted fluorescence at 510 nm (dicroic, DCLP410; emitter filter, LP470; TILL Photonics). FURA-2 signals are given as ratios F340/F380, where F340 and F380 represent the background-subtracted fluorescence intensities at 340 and 380 nm, respectively. For the simultaneous imaging of membrane potential and internal Ca2+, the cells were first loaded for 40 min at room temperature with 10 μm FURA-2 AM (Invitrogen) dissolved in HBSS. Afterward the cells were washed and incubated for further 15 min in FMP-containing HBSS at room temperature. Taking advantage of the filter change capability of the iMIC microscope, we changed the FMP and FURA-2 filter sets automatically during the recordings. In each cycle the FMP filter set was first placed in position, and one image was captured at 530 nm. Subsequently, the FMP filter set was replaced by the FURA-2 filter set, and the images at 340 and 380 nm were acquired. The cycles were repeated every 2 s, and three independent sequences of images containing 10–85 cells/frame were compiled to generate simultaneous time courses of ΔF/F0 and F340/F380. The imaging experiments were repeated 4–5 times, and figures show representative examples of each series. Because FMP is a no-wash dye, all reagents used were dissolved in solutions containing FMP. Concentrated thapsigargin, carbachol, and K+ solutions were applied in a bath to obtain the final concentrations of 1 μm, 130 μm, and 25 mm (high K+ solution), respectively.

Data Analysis

Dose-response curves were fitted with a logistic Hill equation of the form CD = CDmin + ((CDmax − CDmin)/(1 + (EC50/Ca2+i)h)), where CD and Ca2+i denote current densities and internal Ca2+ concentrations, respectively. EC50 is the Ca2+i needed to attain half-maximal CD, and h represents the apparent Hill coefficient. The time courses of inward ion currents were fitted with the exponential decay function I = Imax − ((Imax − Imin)·exp (−t/τfast)), where I and t represent inward current amplitudes and time. τfast denotes the fast activation time constant. Significance was tested by the two sample Student's t tests. Pooled data is given as the mean ± S.E.

RESULTS

Dose-dependent Activation of TRPC5 Channels by Internal Ca2+

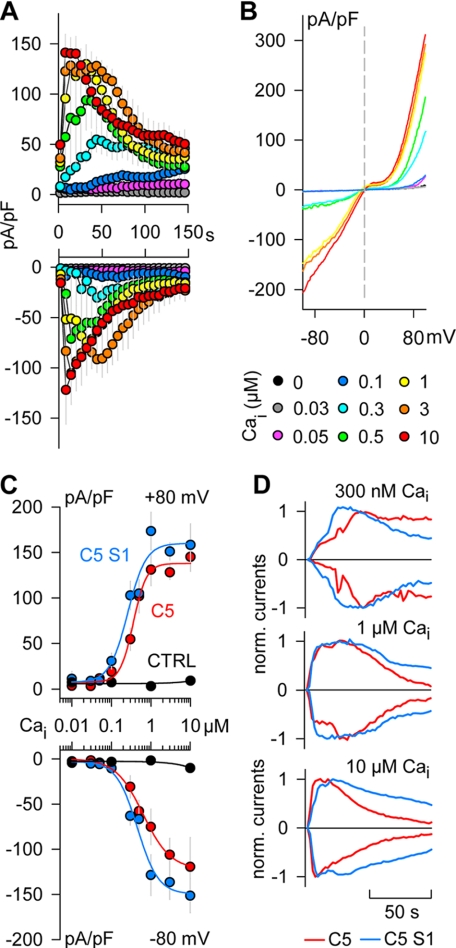

We determined first the Ca2+ sensitivity of TRPC5 channels in the absence of other possible channel modulators and agonists of membrane receptors and G proteins. Fig. 1 shows whole-cell patch clamp experiments that were performed with various internal Ca2+ concentrations (Ca2+i) clamped between 0 and 10 μm. A nominally Ca2+-free (NCaF) bath solution was used to suppress Ca2+ influxes that might distort Ca2+i. Because ATP inhibits TRPC5 channels (36), ATP was not included in the pipette solution. Outward and inward current densities were measured at +80 mV and −80 mV, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1A, we observed a direct TRPC5 current activation just by increasing Ca2+i. Both the time course of current activation became faster, and the peak current densities increased proportionally to Ca2+i. Furthermore, a current decay was observed at higher Ca2+i, suggesting desensitization of TRPC5 channels (37). The shape of the current-voltage (I-V) relations at all Ca2+i concentrations displayed the typical outward and inward rectification as well as the shoulder of 0 slope around +20 mV (Fig. 1B), as has been shown for TRPC5 channels expressed in various cell lines (see Ref. 6). To quantify the Ca2+ sensitivity of TRPC5 channels, we constructed dose-response curves for peak inward and outward currents (Fig. 1C). Fitting the data with a logistic Hill equation revealed that both outward and inward current densities increase in a dose-dependent manner, although with slightly different sensitivities. The maximal densities of inward and outward currents at Ca2+i between 1 and 10 μm were comparable (−122.27 ± 4.64 versus 137.90 ± 4.94 pA/pF). However, the Ca2+i needed to induce half-maximal responses (EC50) was higher for inward currents than for outward currents (635.11 versus 358.20 nm). Conversely, the apparent Hill coefficient was lower for inward currents than for outward currents (1.25 versus 2.61). Furthermore, we found that HEK control cells developed neither outward nor inward currents during dialysis with Ca2+i between 0 and 10 μm (Fig. 2C), ruling out a possible contamination by endogenous currents. Thus, the experiments shown in Fig. 1 indicate that an increase of internal Ca2+ is sufficient to activate TRPC5 channel currents. The different Ca2+ sensitivities of inward and outward currents additionally suggest that internal Ca2+ not only activates TRPC5 channels but also modulates their gating kinetic. Supporting this suggestion, we observed outwardly rectifying currents at all Ca2+i tested, whereas the inward currents became more linear at higher Ca2+i (Fig. 1B). Similar changes in the inward currents have been attributed to a switch between voltage-dependent and voltage-independent gating modes of TRPC5 channels activated via receptor stimulation (38).

FIGURE 1.

Dose-dependent activation of TRPC5 channels by internal Ca2+. A, time course of current densities measured in the TRPC5 cell line after break-in with pipettes containing Ca2+ concentrations (Ca2+i) clamped between 0 (10 mm EGTA) and 10 μm. Ca2+ was not added to the external solution (NCaF). Voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV were delivered every 2 s to elicit ionic currents. Outward and inward current densities were determined at +80 mV (upper panel) and −80 mV (lower panel), respectively, in 4–10 cells for each Ca2+i. Graphs show every third data point. B, representative current-voltage relations obtained in the experiments shown in A with the indicated Ca2+i. Color coding for Ca2+i is the same in A and B. C, dose-response curves for the activation of TRPC5 channel currents by internal Ca2+. Mean peak outward and inward current densities (upper and lower panels, respectively) were determined as in A in the TRPC5 cell line (C5), in non-transfected HEK cells (CTRL), and in TRPC5 cells transiently transfected with STIM1 (C5 S1). Lines represent the best fits of a logistic Hill equation to the outward current data (EC50: 358.20 nm, C5; 260.06 nm, C5 S1. Hill coefficient: 2.61, C5; 1.89, C5 S1) and inward current data (EC50: 635.11 nm, C5; 456.33 nm, C5 S1. Hill coefficient: 1.24, C5; 1.63, C5 S1). Note that control HEK cells show no current activation up to 10 μm Ca2+i. n = 4–10. D, normalized time course of average outward and inward currents for the indicated Ca2+i in cells expressing TRPC5 alone or TRPC5 + STIM1. Color coding for transfection protocols is the same in C and D.

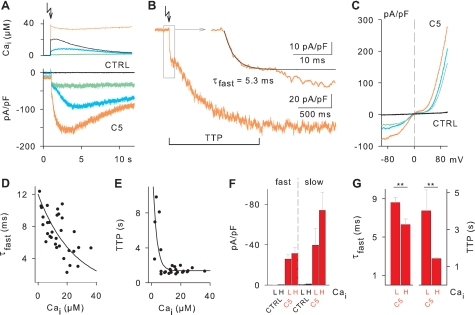

FIGURE 2.

Time course of TRPC5 channel activation upon stepwise increases of Ca2+i. A, shown are flash-evoked increases of Ca2+i (upper panel) and the corresponding continuous recordings of inward currents at −70 mV (lower panel) in a non-transfected HEK cell (CTRL) and in cells stably expressing TRPC5 (C5). Individual TRPC5 cells are color-coded. Cells were dialyzed with a mixture of nitrophenyl-EGTA, FURA-2, and Furaptra to allow stepwise increases of Ca2+i by flash photolysis and simultaneous measurement of Ca2+i. The external solution contained 2 mm Ca2+. The arrow indicates the time point of the flash. B, shown are fast and slow TRPC5 channel activation phases. The time constant for the fast activation (τfast) was determined by fitting exponential functions to the current increases observed during the first 20–40 ms after flash. To quantify the slow activation time course, the TTP was determined in 12 s of continuous current recordings. TTP = 1.34 s. C, current-voltage relationships are shown. Voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV were applied immediately after the continuous current recordings shown in A. D, shown is Ca2+i dependence of τfast. Shown are τfast values of individual cells as a function of Ca2+i. The line represents an approximation using an exponential function. E, shown is Ca2+i dependence of TTP. Data points represent TTP values of single cells that developed a peak current in the 12-s current recording. The line represents an approximated exponential function. F, average increase of inward current densities during the fast and slow phase of TRPC5 channel current activation in experiments with low (L, 1- 10 μm) and high (H, >10 μm) Ca2+i. The increases of current density attained during the fast activation phase were measured at 20- 40 ms after flash and subtracted from peak current densities to determine the amount of current increase during the slow phase of TRPC5 channel current activation (total CTRL, n = 11; total C5, n = 32). Cells with no peak current in the slow phase of activation were not counted in the latter analysis. G, average τfast and TTP of TRPC5 channel current activation in experiments with low and high Ca2+i. Cells with no peak current were not counted in the TTP analysis. τfast: L, n = 13; H, n = 15. TTP: L, n = 9; H, n = 14. **, p < 0.01.

Because it has been shown that STIM1 binds to TRPC5 (23), experiments with various Ca2+i were also performed in TRPC5 cells additionally transfected with STIM1. As shown in Fig. 1C, the Ca2+ sensitivity of TRPC5 channels was not significantly modified by the overexpression of STIM1. Similarly, STIM1 had no significant effect on the time course of TRPC5 current activation (Fig. 1D). Especially at Ca2+i concentrations higher than 0.5 μm, however, we observed slower rates of TRPC5 channel current decay in cells overexpressing STIM1 (Fig. 1D), suggesting that STIM1 modifies the desensitization properties of TRPC5 channels activated by internal Ca2+.

Time Course of the TRPC5 Channel Activation by Internal Ca2+

To elucidate the time course of TRPC5 channel activation, we next performed experiments in which internal Ca2+i was stepwise increased by flash-induced photolysis of caged Ca2+ (see Ref. 33). Inward currents were continuously recorded at −70 mV with a high time resolution. Indeed, TRPC5 cells respond to flash-evoked Ca2+i rises with a rapid activation of an inward current, whereas HEK control cells were not responsive at all (Fig. 2A). The standard response of a TRPC5 cell is characterized by an initial current activation with a time constant (τfast) between 3 and 12 ms and is followed for high Ca2+i concentrations by a subsequent slower phase of TRPC5 activation, reaching the peak current within seconds (TTP, Fig. 2B). Both low and high Ca2+ responses exhibit similar I-V properties with double rectification and 0 slope region, indicative for TRPC5 activity (Fig. 2C).

Proportional to the Ca2+i levels attained by flash photolysis in the individuals cells, τfast decreases from about 12 ms to less than 3 ms for Ca2+i between 2.1 and 36.3 μm (Fig. 2D), supporting the view of a fast Ca2+-dependent activation of TRPC5 channels by intracellular Ca2+ elevations. In the same Ca2+i range, time to peak (TTP) decreased from about 10 s to values around 1.5 s (Fig. 2E), suggesting that also the time course of the slow TRPC5 channel activation is governed by the levels of Ca2+i. In an attempt to quantify statistically the effects of Ca2+i on TRPC5 channel current densities, we pooled the data for cells that were flashed to Ca2+i values below 10 μm (low Ca2+i) and above 10 μm (high Ca2+i). Although the average current amplitude moderately, but not significantly, increased with high Ca2+i flashes, probably due to cell-to-cell variability in current density (Fig. 2F), τfast and TTP were statistically significant longer in low Ca2+i cells (Fig. 2G). On average, τfast and TTP were 8.61 ms and 4.02 s at low Ca2+i and decreased to 6.29 ms and 1.43 s at high Ca2+i, respectively. Notably, the Ca2+i increases induced by uncaging Ca2+ had no effect on the cell membrane capacitance (Cm) of TRPC5 cells (before flash, 13.93 ± 0.41 pF; after flash, 14.02 ± 0.41 pF; n = 32), ruling out the possible involvement of exocytotic processes in the Ca2+-induced activation of TRPC5 channels. Taken together, the photolysis experiments demonstrated a direct activation of TRPC5 channel currents by internal Ca2+ comprising two kinetically distinct phases, a fast activation phase occurring within the first milliseconds followed by a slow phase at the time scale of seconds. The tempo in these activation phases is determined by the Ca2+i level in the cell.

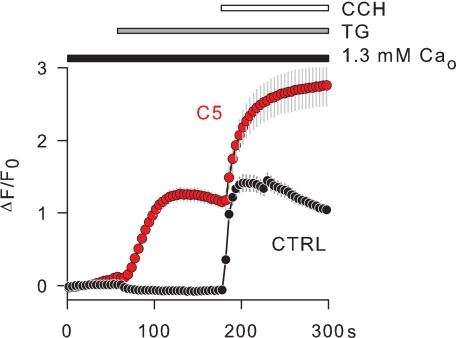

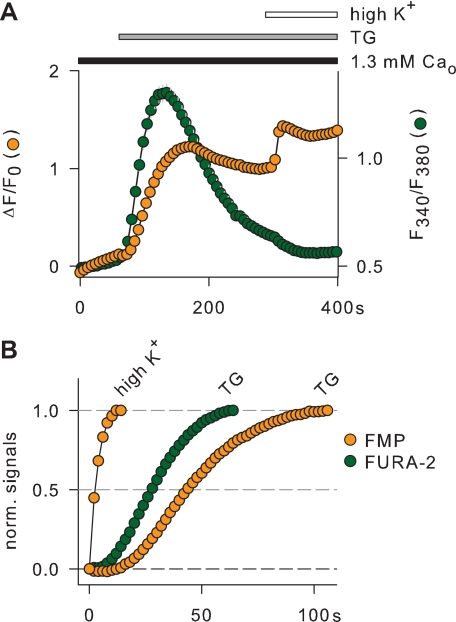

Membrane Depolarization Supported by TRPC5 Ion Channels

Because it is known that the stimulation of transiently transfected histamine receptors induces a membrane depolarization in the TRPC5 cell line (28), we used membrane potential imaging to determine whether the Ca2+ mobilization activates TRPC5 channels in intact, non voltage-clamped cells. Fig. 3 shows single cell imaging experiments with the FLIPR membrane potential dye (FMP, see Ref. 34), in which TRPC5 cells were exposed consecutively to thapsigargin and carbachol. Under these conditions it was expected that the Ca2+ mobilization preceded the activation of the phospholipase C signaling pathway. Thapsigargin induced a strong depolarization in TRPC5 cells but had no effect at all in control HEK cells, whereas carbachol depolarized both TRPC5 and control cells, indicating that the thapsigargin effects were selective for the TRPC5 cell line (Fig. 3). Because thapsigargin induces a similar Ca2+ mobilization in TRPC5 and control HEK cells (not shown), we presumed that the activation of TRPC5 channels by internal Ca2+ underlay the membrane depolarization induced selectively by thapsigargin in TRPC5 cells. Admittedly, this hypothesis implied that the increase of internal Ca2+ preceded the membrane depolarization. We analyzed, therefore, the thapsigargin effects in TRPC5 cells using simultaneous imaging of membrane depolarization and internal Ca2+ with FMP and FURA-2, respectively (Fig. 4A). To compare time courses, we normalized the thapsigargin-induced rise of FMP and FURA-2 signals and measured the time to half-maximum increase (τ½). Fig. 4B shows that FURA-2 signals appeared about 22 s earlier than FMP signals (FURA-2: τ½ = 33.82 ± 0.98 s; FMP: τ½ = 55.94 ± 4.57 s; n = 72). To estimate the celerity of FMP responses, high K+ was applied at the end of the experiments (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4B, the FMP signals in high K+ rose with a τ½ of 4.55 ± 0.28 s; that is, ∼7 times faster than thapsigargin-induced FURA-2 signals, indicating that the FMP response to membrane depolarization is not a rate-limiting step in our assay system. Thus, the increase of internal Ca2+ in response to thapsigargin preceded the membrane depolarization, suggesting that this increase of internal Ca2+ activates TRPC5 channels, which generate a membrane depolarization in TRPC5 cells.

FIGURE 3.

Membrane depolarization induced by Ca2+ mobilization in cells expressing TRPC5. Cells were exposed to thapsigargin (TG, 1 μm) and carbachol (CCH, 130 μm) as indicated above the graphs. The external Ca2+ concentration (Ca2+o) was 1.3 mm. Changes in the membrane potential were imaged with the FMP dye. Relative changes of the FMP fluorescence intensity (ΔF/Fo) are shown for TRPC5 cells (C5, n = 41) and for non-transfected HEK cells (CTRL, n = 59). Positive ΔF/Fo values reflect membrane depolarization.

FIGURE 4.

Simultaneous imaging of membrane potential and internal Ca2+ during thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ mobilization in the TRPC5 cell line. Thapsigargin (TG, 1 μm) was applied in the presence of 1.3 mm external Ca2+ (Ca2+o) as indicated above the graph. To determine the maximal FMP response, cells were additionally exposed to high K+ (25 mm). Changes in membrane potential and internal Ca2+ were imaged using FMP and FURA-2 and are given as ΔF/Fo and F340/F380, respectively. After the application of thapsigargin, the FURA-2 signal rose before the FMP signal (A, n = 81). The normalized FMP and FURA-2 signals indicate that the rise of internal Ca2+ preceded the membrane depolarization in cells expressing TRPC5 (B).

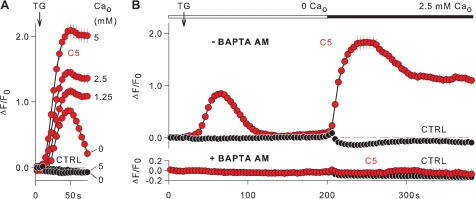

Because the Ca2+ mobilization induced by thapsigargin is composed of Ca2+ release from internal stores and Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space, we next examine the role of external and internal Ca2+ in the TRPC5-mediated depolarization (Fig. 5). At external Ca2+ concentrations (Ca2+o) between 1.25 and 5 mm, the membrane depolarizations induced by thapsigargin reached plateaus that were proportional to Ca2+o (Fig. 5A). By contrast, the membrane depolarization in the absence of external Ca2+ was transient. Thapsigargin had no effect on the membrane potential of non-transfected HEK cells at 0 and 5 mm Ca2+o (Fig. 5A), supporting the suggestion that the membrane depolarization induced by thapsigargin in the TRPC5 cell line reflects the opening of TRPC5 channels. Thus, the different responses of TRPC5 cells in the presence and absence of external Ca2+ suggest that Ca2+ release and Ca2+ entry determine the time course of TRPC5 channel activation. Using the so-called Ca2+ re-addition protocol, we dissected the time courses of TRPC5 channel activation induced by Ca2+ release from internal stores and by Ca2+ entry. Fig. 5B, upper panel, shows that the Ca2+ release produces a transient depolarization, whereas the Ca2+ entry supports a sustained membrane depolarization. To confirm that internal Ca2+ mediates the activation of TRPC5 channels, cells were loaded with BAPTA AM. Under these conditions (Fig. 5B, lower panel), both the membrane depolarization induced by Ca2+ release and Ca2+ entry were abolished in TRPC5 cells. Non-transfected HEK cells showed no membrane depolarization at all in the presence or absence of the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA. Thus, the Ca2+ release and Ca2+ entry activate of TRPC5 channels with different time courses, whereby a sustained TRPC5 channel activation and a sustained membrane depolarization are attained only by Ca2+ entry.

FIGURE 5.

Dependence of the TRPC5-mediated membrane depolarization on external and internal Ca2+. Ca2+ mobilization was induced with thapsigargin (TG, 1 μm) in TRPC5 cells (C5) and in non-transfected HEK cells (CTRL). As indicated, external Ca2+ (Ca2+o) varied between 0 and 5 mm. The 0 mm Ca+ solution contained 0.5 mm EGTA (0 Ca2+o). Experiments were carried out with cells preloaded with the cell-permeant BAPTA AM (+BAPTA AM) and with non-treated cells (−BAPTA AM). Changes in membrane potential were imaged using FMP and are given as ΔF/Fo. A, TRPC5 cells exposed to thapsigargin developed a sustained membrane depolarization that was boosted by increasing Ca2+o between 1.25 and 5 mm (n = 48 and 65, respectively). In 0 Ca2+o, the membrane depolarization of TRPC5 cells was transient (n = 59). No membrane depolarization was observed in control cells exposed to thapsigargin in 0 and 5 mm Ca2+o (n = 56 and 60). B, thapsigargin elicited a transient membrane depolarization in 0 Ca2+o, and the subsequent re-addition of 2.5 mm Ca2+o induced a sustained membrane depolarization in TRPC5 cells that were not pre-loaded with BAPTA AM (upper panel, −BAPTA AM, n = 63). Neither thapsigargin nor Ca2+ re-addition evoked a membrane depolarization in TRPC5 cells pre-loaded with BAPTA AM (lower panel, +BAPTA AM, n = 65). Independently of the BAPTA AM preloading, control cells showed no membrane depolarization in the Ca2+ re-addition protocol (upper and lower panels; n = 61 and 57, respectively).

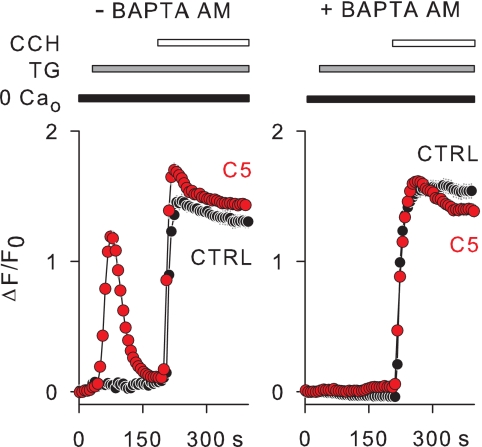

Fig. 3 showed that stimulation of membrane receptors by carbachol-depolarized TRPC5 cells as well as control HEK cells after depletion of internal Ca2+ stores by thapsigargin. To explore the possibility that agonist stimulation of membrane receptors might activate TRPC5 channels independently of changes in the internal Ca2+ concentration, cells were loaded with BAPTA AM. The experiments were carried out in the absence of external Ca2+ to prevent Ca2+ entry. As in Fig. 3, thapsigargin and carbachol were applied sequentially. Fig. 6 illustrates that carbachol depolarized both control and TRPC5 cells to a similar extent independently of the presence of the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA. Thus, the agonist stimulation of membrane receptor appears to have no effect on TRPC5 channel activation when the Ca2+ mobilization is abrogated.

FIGURE 6.

Lack of TRPC5 channel activation under strong buffering of internal Ca2+ with BAPTA. Membrane depolarization was induced with carbachol (CCH, 130 μm) after depletion of internal Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin (TG, 1 μm) in TRPC5 (C5) and non-transfected HEK (CTRL) cells that were either non-treated (left panel, −BAPTA AM) or preloaded with BAPTA AM (right panel, +BAPTA AM). The bath solution contained 0.5 mm EGTA (0 Ca2+o). Changes in membrane potential were imaged using FMP and are given as ΔF/Fo. n = 35–65.

Ca2+-mediated Coupling of TRPC5 to Ca2+-selective Ion Channels

Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and the CRAC channels formed by STIM1 and ORAI1 are common forms of Ca2+-selective ion channels that allow Ca2+ entry in response to membrane depolarization and Ca2+ store depletion (39). The ensuing accumulation of Ca2+ in microdomains close to the plasma membrane gives rise to spatially and temporally distinct Ca2+ signals that control nearby ion channels, exchangers, and pumps (39).

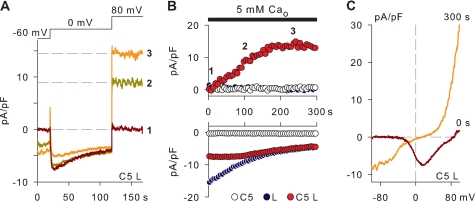

Using murine α1C and β2 subunits of L-type Ca2+ channels, we explored the possibility that the local Ca2+i rise induced by the opening of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels activates TRPC5 channels. This approach has the advantage that the Ca2+ entry can be induced solely by depolarizing the membrane. Fig. 7A illustrates the voltage step protocol used to activate voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and the corresponding current traces. At 0 mV, no current flow through TRPC5 channels was expected (e.g. Fig. 1B), and therefore, current recorded at 0 mV represents primarily Ca2+ channel currents. The amplitude of TRPC5 channel current was monitored at +80 mV, i.e. where Ca2+ channel currents were negligible. As illustrated in Fig. 7, A and B, the amplitude of ion currents at +80 mV increased progressively during the repeated activation of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, whereas the current at 0 mV showed little change (n = 6). These time courses were not observed in cells expressing only TRPC5 or voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (n = 3–5; Fig. 7B). To determine the I-V relations, voltage ramps were applied at the beginning and at the end of the experiment. Fig. 7C illustrates that a typical Ca2+ channel I-V relation was recorded before the train of voltage steps was applied, whereas at the end a clearly double-rectifying I-V was observed. Thus, it appears that the activation of TRPC5 channels can be coupled to the Ca2+ entry through voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ channels.

FIGURE 7.

Activation of TRPC5 channels via Ca2+ entry through L-type Ca2+ channels. Experiments were performed on TRPC5 cells transiently transfected with the murine α1C and β2 subunits of L-type Ca2+ channels (C5 L). Controls were TRPC5 cells (C5) and HEK cells transiently transfected with L-type Ca2+ channels (L). The external Ca2+ concentration (Ca2+o) was 5 mm, and the pipette solution contained 10 mm EGTA. A, ion currents through Ca2+ channels and TRPC5 channels were elicited every 2 s by stepwise depolarizations to 0 and +80 mV from a holding potential of −60 mV, as indicated. Shown are representative examples of current traces recorded in a TRPC5 cell expressing L-type Ca2+ channels at the time points indicated in B. B, time course of ion currents at +80 mV (upper panel) and 0 mV (lower panel) obtained in representative experiments with cells expressing either TRPC5, L-type Ca2+ channels, or TRPC5 plus L-type Ca2+ channels. Every third data point is shown. C, current-voltage relations were determined with voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV at the beginning (0 s) and end (300 s) of the experiment. Shown are the current-voltage relations recorded in the experiment shown in A.

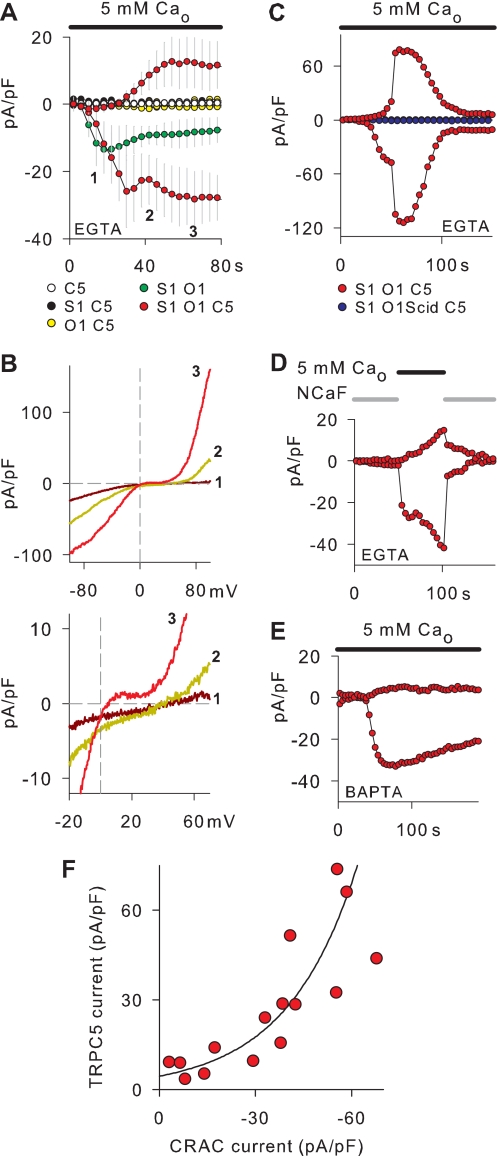

Using murine STIM1 and ORAI1 (31), we explored the possibility that the local Ca2+i rise induced by the opening of CRAC channels activates TRPC5 channels. In the first experiments, various combinations of TRPC5, ORAI1, and STIM1 were transfected into HEK cells to determine the channel proteins needed to establish a time dependence between CRAC and TRPC5 channel current activation. Following the conventional approach to activate CRAC channels in whole-cell patch clamp experiments (e.g. Ref. 31), the transfected cells were dialyzed with IP3. The external Ca2+ concentration (Ca2+o) was 5 mm, and Ca2+i was clamped with 10 mm EGTA to allow CRAC channel activation. Fig. 8A shows that no ion current was observed in cells expressing either TRPC5 alone or in combination with STIM1 or ORAI1. Cells expressing STIM1 + ORAI1 displayed only inwardly rectifying ion currents, as previously described (31). By contrast, cells transfected with TRPC5 + STIM1 + ORAI1 developed both inward and outward currents upon dialysis with IP3. To identify the ion channels activated by IP3 dialysis in cells expressing TRPC5 + STIM1 + ORAI1, we analyzed the temporal changes in the I-Vs as illustrated in Fig. 8B, upper panel. Earlier in the recordings, the I-Vs reflected the opening of CRAC channels, as only inwardly rectifying currents were observed (31). At later times in the recording, we observed a progressive increase of both inward and outward currents that built up the typical I-V of TRPC5 channels with double rectification and a 0 slope region around +20 mV. As expected for the opening of CRAC and TRPC5 channels in a row, the reversal potential shifted from +46 to +5 mV in this particular example (Fig. 8B, lower panel). Thus, the activation of TRPC5 currents can be directly coupled to the activation of CRAC currents, suggesting that the Ca2+ entry through Ca2+-selective channels can serve as a Ca2+ source for the activation of TRPC5 channels In the experiments shown in Fig. 8, A and B, we used 10 mm EGTA as the internal Ca2+ buffer to allow CRAC channel activation, but it is likely that this buffer also restricted the effects of Ca2+ influx on TRPC5 channels. Therefore, it is not surprising that the small endogenous CRAC currents of HEK cells (31) failed to activate TRPC5 channels in the experiments with cells expressing either TRPC5 alone or in combination with STIM1 or ORAI1.

FIGURE 8.

Activation of TRPC5 channels via Ca2+ entry through CRAC channels. HEK cells were transiently transfected with STIM1 (S1), ORAI1 (O1), and TRPC5 (C5) in the indicated combinations (A and B). The TRPC5 cell line (C5) was transiently transfected with STIM1 and either ORAI1 or the Scid mutant of ORAI1 (O1Scid) C–E, cells were dialyzed with IP3 (20 μm) and either 10 mm EGTA or 10 mm BAPTA. The external Ca2+ concentration (Ca2+o) was 5 mm. Voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV were delivered every 2 s. Outward and inward current densities were determined at +80 mV and −80 mV, respectively. A, co-expression of STIM1 and ORAI1 is required to activate TRPC5 channel currents in cell dialyzed with IP3. Shown are average time courses of outward and inward currents in 3–10 cells for each transfection protocol. Every second data point is shown. B, current-voltage relations obtained in a cell expressing STIM1+ORAI1+TRPC5 at the time points indicated in A (upper panel). The sections of the current voltage relations around +20 mV are expanded to illustrate changes in the reversal potential (lower panel). C, inhibition of CRAC and TRPC5 channel current activation by the ORAI1 Scid mutant. Shown is a representative cell expressing STIM1+ORAI1 Scid +TRPC5 and a control with STIM1+ORAI1+TRPC5. D, turning CRAC currents off and on is shown. A NCaF solution was present in the bath to suppress CRAC currents, and the solution containing 5 mm Ca2+o was locally applied as indicated above the graph to allow CRAC current flow. E, uncoupling of CRAC and TRPC5 channel current activation by BAPTA in cells expressing STIM1+ORAI1+TRPC5 is shown. The example cell shows that only inward current increases were detected in cells dialyzed with IP3 and BAPTA. F, correlation between TRPC5 and CRAC channel currents densities in the TRPC5 cell line transiently transfected with STIM1 + ORAI1 is shown. CRAC channels were activated as in C. CRAC current densities were measured at −80 mV at time points before the development of significant outward currents. TRPC5 current densities represent the maximal values obtained at +80 mV during the experiment. Each data point represents an individual cell. The line represents an approximated exponential rise.

To strengthen the role of Ca2+ influx in the activation of TRPC5 channels, we used a nonfunctional mutant of ORAI1 and turned the Ca2+ flux through CRAC channels off and on. The nonfunctional ORAI1 mutant was created by introducing the Scid mutation described for human ORAI1 (32) into murine ORAI1. When this Scid ORAI1 mutant was transfected with STIM1 in HEK cells, the ion currents were close to the limit of resolution and significantly smaller than endogenous CRAC currents, indicating that the Scid ORAI1 mutant exerts a dominant-negative effect on endogenous CRAC currents (supplemental Fig. 1). Taking advantage of this dominant-negative effect, Scid ORAI1 and STIM1 were co-transfected into the TRPC5 cell line to abrogate CRAC channel function (32). The activation of CRAC and TRPC5 channel currents was assayed in the transfected cells following the rationale of the experiments in Fig. 8A. In all cells tested (n = 6), neither outward nor inward currents were detectable (Fig. 8C). Thus, functional CRAC channels are required to activate TRPC5 channels in cells expressing TRPC5 + ORAI1 + STIM1. Furthermore, Fig. 8C shows that the activation of TRPC5 channel currents seen in the transient transfection experiments with TRPC5 + ORAI1 + STIM1 (Fig. 8A) can be reproduced by expressing ORAI1 + STIM1 in the TRPC5 cell line (n = 15). To turn the Ca2+ flux through CRAC channels off in these cells, we used a NCaF external solution that contained traces of Ca2+ (31). Additionally, NCaF contained 2 mm Mg2+ to block Na+ currents, and therefore, no current flow through CRAC channels was expected in the presence of NCaF (31). In fact, neither outward nor inward currents were observed in TRPC5 cells additionally transfected with STIM1 and ORAI1 (n = 4) in the presence of NCaF (Fig. 8D). The superfusion of a bath solution containing 5 mm Ca2+o turned on immediately the typical inwardly rectifying CRAC currents, and subsequently, both outward and inward currents increased, suggesting that the Ca2+ entry through CRAC channels is sufficient and necessary to trigger the activation of TRPC5 channels in cells expressing TRPC5 + ORAI1 + STIM1. Supporting the involvement of Ca2+ entry in the TRPC5 channel activation, the subsequent superfusion of NCaF suppressed both outward and inward currents (Fig. 8D).

Because the proximity between Ca2+ sources and Ca2+-activated channels can be assessed by comparing the effects of equal concentrations of EGTA and BAPTA (39, 40), we performed experiments with 10 mm BAPTA in TRPC5 cells additionally transfected with ORAI1 and STIM1. As illustrated in Fig. 8E, no outward current activation was observed upon dialysis of IP3 in the presence of BAPTA (n = 4). Only CRAC currents were recorded in the BAPTA experiments (cf. Fig. 8, A and E, and Ref. 31), indicating that BAPTA disrupts the coupling of Ca2+ entry through CRAC channels to TRPC5 channel activation. Importantly, the comparison between the EGTA and BAPTA data suggests furthermore that a local rather than a global rise of internal Ca2+ underlies the coupling between Ca2+ entry and TRPC5 channel activation (cf. Fig. 8, C and E). Indeed, we observed a direct correlation between TRPC5 and CRAC channel current densities in cells expressing TRPC5 + ORAI1 + STIM1 (Fig. 8F), suggesting a functional coupling between TRPC5 and CRAC channels.

DISCUSSION

The present series of experiments were designed to study the activation of TRPC5 channels by internal Ca2+. Using whole-cell dialysis and photolysis of caged Ca2+, we demonstrate that increases of internal Ca2+ are essential and sufficient for the activation of TRPC5 channels. Submicromolar Ca2+i activates TRPC5 channels in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, stepwise Ca2+i increases activate TRPC5 channels at a millisecond time scale. We also show that the Ca2+ entry through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels as well as through CRAC channels can trigger TRPC5 channel activation via a local rise of internal Ca2+, providing direct evidence that TRPC5 channels are functionally coupled to Ca2+-selective ion channels.

TRPC5 possesses two binding sites for calmodulin in the C-terminal region (CIRB and CCBII; see Ref. 30). CIRB is conserved in all TRPC members and are essential for channel function, as mutations in this binding site make TRPC5 channels non-functional (28). Deletion of CCBII abolishes the facilitation of TRPC5 channel by calmodulin, indicating that both CIRB and CCBII play essential roles in the activation of TRPC5 channels via Ca2+-calmodulin (28). Here we show that the level and time course of TRPC5 channel current activation are determined by Ca2+i in a dose-dependent manner. The responses of inward and outward TRPC5 channel currents to increases of Ca2+i differed in their EC50 (635.11 versus 358.20 nm). Furthermore, the inward currents were more linear at higher Ca2+i, suggesting that the gating mode of TRPC5 channels is also altered by Ca2+i. This effect of high Ca2+i resembles the switch between voltage-dependent and voltage-independent gating modes of TRPC5 channels activated via receptor stimulation (38), and therefore, an interaction between voltage-dependent gating and internal Ca2+ likely underlie the disproportional changes of outward and inward currents activated by the increase of Ca2+i.

In a number of previous studies, TRPC5 channels have been activated either via stimulation of G protein-coupled membrane receptors or via direct activation of G proteins (5, 6). We found that the activation of TRPC5 channel currents by carbachol and epidermal growth factor is abolished in 0 Ca2+i (supplemental Fig. 2), supporting the conclusion that internal Ca2+ is essential for the activation of TRPC5 channels. Recently, it has been shown that phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate has both positive and negatives effects on the activation of TRPC5 via membrane receptors (41). In our hands the phospholipase C inhibitor U73122 had no effect on the Ca2+-dependent activation of TRPC5 (supplemental Fig. 2). Previous studies also suggested that the TRPC5 channel activation is determined by vesicular transport and Ca2+-regulated exocytosis (18). Several lines of evidence are difficult to reconcile with such an activation mechanism in our experiments. We found that TRPC5 channels activated rapidly by flash-induced Ca2+i rises, but the channel activation was not accompanied by a significant increase in membrane capacitance. In the same line, disruption of the cytoskeleton with cytochalasin D, which facilitates the fusion of secretory vesicles with the plasma membrane in pancreatic acinar cells (42), had no effect on the action of internal Ca2+ in the range of 0–1 μm (supplemental Fig. 2). Other mechanisms of TRPC5 channel activation such as the initially proposed store-operated mechanism (21) can be readily interpreted on the basis of the present results as being mediated by the increase of Ca2+i that naturally occurs after depletion of internal Ca2+ stores. Therefore, it is safe to conclude that the ultimate mechanism leading to activation of TRPC5 channel is the rise of internal Ca2+. As suggested previously (27), internal Ca2+ also potentiates the effects of agonists such carbachol on TRPC5 channels (supplemental Fig. 2). Finally, the action of lanthanides on TRPC5 channels has been tested so far at basal Ca2+i levels (12, 13), and no information is available on whether the activation occurs in the absence of internal Ca2+ as well. In our hands, gadolinium had no effect on TRPC5 channel currents at 0 Ca2+i, but enhanced TRPC5 channel currents that have been previously activated by 100 nm Ca2+i (supplemental Fig. 3), supporting again the suggestion that increases of Ca2+i are essential and sufficient to activate TRPC5 channels.

Finally, the experiments with TRPC5, STIM1, and ORAI1 recapitulate the main features of a functional coupling between TRPC5 channels and Ca2+-selective channels. Considering that the local rise of Ca2+i is sufficient to activate TRPC5 channels, the results of the present study allow the suggestion that the ion channels formed by TRPC5 belong to the group of Ca2+-activated non-selective channels that were initially described in cardiac cells (43). As in other Ca2+-activated non-selective channels formed by TRPM4 and TRPM5 (44, 45), TRPC5 channels are activated by submicromolar Ca2+i. However, TRPC5 channels are unique in that they are modulated via multiple mechanisms that provide the basis for the integration of electrical and humoral signals. Internal Ca2+ potentiates at least the effects of agonist stimulation of membrane receptors on TRPC5 channels (27). Thus, it is likely that internal Ca2+ acts cooperatively or synergistically with other intracellular signaling molecules in the activation of TRPC5 channels. In this scenario the Ca2+-dependent activation of TRPC5 channels is coupled to the opening of Ca2+-selective ion channels, and the simultaneous stimulation of membrane receptors leads to a further modulation of the TRPC5 channel currents. By mediating Na+ influx, TRPC5 channels might support membrane depolarization depending on their expression levels and on the input resistance of the cell. Here we show that the coupling of TRPC5 channel activation to Ca2+ entry underlies long-lasting membrane depolarizations. Future experiments might determine whether TRPC5 channels are tightly coupled to Ca2+-selective channels, as has been reported for Ca2+-activated K+ channels (46), or they are randomly distributed, as shown for the arrangement of secretory vesicles and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in neuroendocrine cells (47).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. V. Flockerzi for thoughtful comments and Heidi Löhr and Karin Wolske for precious technical help.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to D. B. and A. C.). This work was also supported, in whole or in part, by the National Institutes of Health and by the American Heart Association (to M. X. Z.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs 1–3.

- TRP

- transient receptor potential

- TRPC

- canonical TRP

- HEK cell

- human embryonic kidney cell

- CRAC

- calcium-release-activated-calcium

- FMP

- FLIPR membrane potential

- NCaF

- nominally Ca2+-free

- pF

- picofarads

- IP3

- inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- HBSS

- Hanks' balanced salt solution

- Ca2+o

- external Ca2+ concentration

- Ca2+i

- internal Ca2+ concentration

- TTP

- time to peak.

REFERENCES

- 1.Venkatachalam K., Montell C. (2007) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 387–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abramowitz J., Birnbaumer L. (2009) FASEB J. 23, 297–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trebak M., Lemonnier L., Smyth J. T., Vazquez G., Putney J. W., Jr. (2007) Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 179, 593–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietrich A., Kalwa H., Rost B. R., Gudermann T. (2005) Pflügers Arch. 451, 72–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beech D. J. (2007) Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 179, 109–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plant T. D., Schaefer M. (2005) Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 371, 266–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hui H., McHugh D., Hannan M., Zeng F., Xu S. Z., Khan S. U., Levenson R., Beech D. J., Weiss J. L. (2006) J Physiol. 572, 165–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greka A., Navarro B., Oancea E., Duggan A., Clapham D. E. (2003) Nat. Neurosci. 6, 837–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riccio A., Li Y., Moon J., Kim K. S., Smith K. S., Rudolph U., Gapon S., Yao G. L., Tsvetkov E., Rodig S. J., Van't Veer A., Meloni E. G., Carlezon W. A., Jr., Bolshakov V. Y., Clapham D. E. (2009) Cell 137, 761–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu S. Z., Sukumar P., Zeng F., Li J., Jairaman A., English A., Naylor J., Ciurtin C., Majeed Y., Milligan C. J., Bahnasi Y. M., Al-Shawaf E., Porter K. E., Jiang L. H., Emery P., Sivaprasadarao A, Beech D. J. (2008) Nature 451, 69–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semtner M., Schaefer M., Pinkenburg O., Plant T. D. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33868–33878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung S., Mühle A., Schaefer M., Strotmann R., Schultz G., Plant T. D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 3562–3571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strübing C., Krapivinsky G., Krapivinsky L., Clapham D. E. (2001) Neuron 29, 645–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshida T., Inoue R., Morii T., Takahashi N., Yamamoto S., Hara Y., Tominaga M., Shimizu S., Sato Y., Mori Y. (2006) Nat. Chem. Biol. 2, 596–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomis A., Soriano S., Belmonte C., Viana F. (2008) J. Physiol. 586, 5633–5649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flemming P. K., Dedman A. M., Xu S. Z., Li J., Zeng F., Naylor J., Benham C. D., Bateson A. N., Muraki K., Beech D. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4977–4982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhuri P., Colles S. M., Bhat M., Van Wagoner D. R., Birnbaumer L., Graham L. M. (2008) Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 3203–3211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bezzerides V. J., Ramsey I. S., Kotecha S., Greka A., Clapham D. E. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 709–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao Y., Plummer N. W., George M. D., Abramowitz J., Zhu M. X., Birnbaumer L. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 3202–3206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng F., Xu S. Z., Jackson P. K., McHugh D., Kumar B., Fountain S. J., Beech D. J. (2004) J Physiol. 559, 739–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Philipp S., Hambrecht J., Braslavski L., Schroth G., Freichel M., Murakami M., Cavalié A., Flockerzi V. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 4274–4282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma H. T., Peng Z., Hiragun T., Iwaki S., Gilfillan A. M., Beaven M. A. (2008) J. Immunol. 180, 2233–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuan J. P., Zeng W., Huang G. N., Worley P. F., Muallem S. (2007) Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 636–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeHaven W. I., Jones B. F., Petranka J. G., Smyth J. T., Tomita T., Bird G. S., Putney J. W., Jr. (2009) J. Physiol. 587, 2275–2298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaefer M., Plant T. D., Obukhov A. G., Hofmann T., Gudermann T., Schultz G. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 17517–17526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okada T., Shimizu S., Wakamori M., Maeda A., Kurosaki T., Takada N., Imoto K., Mori Y. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 10279–10287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blair N. T., Kaczmarek J. S., Clapham D. E. (2009) J. Gen. Physiol. 133, 525–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ordaz B., Tang J., Xiao R., Salgado A., Sampieri A., Zhu M. X., Vaca L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30788–30796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinoshita-Kawada M., Tang J., Xiao R., Kaneko S., Foskett J. K., Zhu M. X. (2005) Pflugers Arch. 450, 345–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu M. X. (2005) Pflügers Arch. 451, 105–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gross S. A., Wissenbach U., Philipp S. E., Freichel M., Cavalié A., Flockerzi V. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 19375–19384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feske S., Gwack Y., Prakriya M., Srikanth S., Puppel S. H., Tanasa B., Hogan P. G., Lewis R. S., Daly M., Rao A. (2006) Nature 441, 179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borisovska M., Zhao Y., Tsytsyura Y., Glyvuk N., Takamori S., Matti U., Rettig J., Südhof T., Bruns D. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 2114–2126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baxter D. F., Kirk M., Garcia A. F., Raimondi A., Holmqvist M. H., Flint K. K., Bojanic D., Distefano P. S., Curtis R., Xie Y. (2002) J. Biomol. Screen 7, 79–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aneiros E., Philipp S., Lis A., Freichel M., Cavalié A. (2005) J. Immunol. 174, 119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dattilo M., Penington N. J., Williams K. (2008) Mol. Pharmacol. 73, 42–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu M. H., Chae M., Kim H. J., Lee Y. M., Kim M. J., Jin N. G., Yang D. K., So I., Kim K. W. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 289, C591–C600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obukhov A. G., Nowycky M. C. (2008) J. Cell. Physiol. 216, 162–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parekh A. B. (2008) J. Physiol. 586, 3043–3054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neher E. (1998) Neuron 20, 389–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trebak M., Lemonnier L., DeHaven W. I., Wedel B. J., Bird G. S., Putney J. W., Jr. (2009) Pflügers Arch. 457, 757–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muallem S., Kwiatkowska K., Xu X., Yin H. L. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 128, 589–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colquhoun D., Neher E., Reuter H., Stevens C. F. (1981) Nature 294, 752–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ullrich N. D., Voets T., Prenen J., Vennekens R., Talavera K., Droogmans G., Nilius B. (2005) Cell Calcium 37, 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Launay P., Fleig A., Perraud A. L., Scharenberg A. M., Penner R., Kinet J. P. (2002) Cell 109, 397–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berkefeld H., Sailer C. A., Bildl W., Rohde V., Thumfart J. O., Eble S., Klugbauer N., Reisinger E., Bischofberger J., Oliver D., Knaus H. G., Schulte U., Fakler B. (2006) Science 314, 615–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klingauf J., Neher E. (1997) Biophys. J. 72, 674–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.