Abstract

Protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) is a G protein-coupled receptor irreversibly activated by extracellular proteases. Activated PAR2 couples to multiple heterotrimeric G-protein subtypes including Gαq, Gαi, and Gα12/13. Most activated G protein-coupled receptors are rapidly desensitized and internalized following phosphorylation and β-arrestin binding. However, the role of phosphorylation in regulation of PAR2 signaling and trafficking is not known. To investigate the function of phosphorylation, we generated a PAR2 mutant in which all serines and threonines in the C-tail were converted to alanines and designated it PAR2 0P. In mammalian cells, the addition of agonist induced a rapid and robust increase in phosphorylation of wild-type PAR2 but not the 0P mutant, suggesting that the major sites of phosphorylation occur within the C-tail domain. Moreover, desensitization of PAR2 0P signaling was markedly impaired compared with the wild-type receptor. Wild-type phosphorylated PAR2 internalized through a canonical dynamin, clathrin- and β-arrestin-dependent pathway. Strikingly, PAR2 0P mutant internalization proceeded through a dynamin-dependent but clathrin- and β-arrestin-independent pathway in both a constitutive and agonist-dependent manner. Collectively, our studies show that PAR2 phosphorylation is essential for β-arrestin binding and uncoupling from heterotrimeric G-protein signaling and that the presence of serine and threonine residues in the PAR2 C-tail hinder constitutive internalization through a non-canonical pathway. Thus, our studies reveal a novel function for phosphorylation that differentially regulates PAR2 desensitization and endocytic trafficking.

Introduction

Protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2)3 is a member of the protease-activated G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family that includes PAR1, PAR3, and PAR4 (1). PAR2 is expressed in intestinal and airway epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and in a variety of cell types of the vasculature and functions in inflammatory processes associated with tissue injury. PAR2 is also expressed in certain types of metastatic cancers and stimulates tumor cell migration and invasion (2, 3). Multiple extracellular proteases cleave and activate PAR2 including trypsin, mast cell tryptase, and the coagulation protease factor VIIa in complex with tissue factor and Xa and others, but not thrombin (4–6). Similar to other PARs, proteolytic cleavage of PAR2 results in the formation of a new amino terminus that acts like a tethered ligand by binding intramolecularly to the receptor to trigger transmembrane signaling (4, 7). Synthetic peptides that mimic the tethered ligand sequence of the newly exposed amino terminus can activate PAR2 independent of proteolytic cleavage. Upon activation, PAR2 couples to multiple heterotrimeric G-protein subtypes including Gαq, Gαi, and Gα12/13, which signal to a variety of effectors and promotes diverse cellular responses (1). Unlike other PARs, however, activated PAR2 also signals independently of G-proteins through its interaction with β-arrestins, which promotes sustained mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, actin remodeling, and cell migration (8–10). The molecular determinants that specify PAR2 coupling to distinct heterotrimeric G-protein subtypes and binding to β-arrestins remain to be determined.

The known regulatory processes that control GPCR signaling are based largely on studies of the β2-adrenergic receptor (11). In the classic paradigm, ligand-activated GPCRs are rapidly phosphorylated on serine and threonine residues localized within the third intracellular loop or cytoplasmic tail (C-tail) by G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs). β-Arrestins are then rapidly recruited and associate with activated and phosphorylated GPCRs at the plasma membrane. The binding of β-arrestins to activated and phosphorylated GPCRs mediates receptor uncoupling from G-proteins and facilitates receptor internalization (12–14). Once internalized, some GPCRs signal from intracellular compartments through stable interaction with β-arrestins, which functions as a scaffold and transducer of MAP kinase signaling independent of G-proteins (15). Internalized GPCRs are then targeted to recycling endosomes, dephosphorylated, and returned to the cell surface, or sorted to lysosomes and degraded.

Unlike most classic GPCRs, PAR2 is irreversibly activated by extracellular proteases. Thus, we hypothesize that PAR2 signal regulatory mechanisms are likely unique because most other GPCRs are reversibly activated. We previously reported that β-arrestins are essential for activated PAR2 desensitization and internalization. Indeed, in mouse embryonic fibroblasts deficient in β-arrestin 1 and 2 expression, PAR2 desensitization was significantly impaired compared with wild-type β-arrestin expressing cells (16). Internalization of activated PAR2 was also virtually abolished in cells lacking β-arrestin 1 and 2 expression (16). The binding of β-arrestins to activated GPCRs is known to involve multiple interactions with the receptor intracellular loops and C-tail (17). Interestingly, activated PAR2 C-tail truncation mutants displayed normal agonist-induced internalization, caused rapid redistribution of β-arrestins to the plasma membrane, and desensitized in an β-arrestin-dependent manner similar to wild-type PAR2 (16), suggesting that the C-tail of PAR2 is not critical for rapid β-arrestin recruitment. However, activated PAR2 C-tail mutants lost the capacity to form stable complexes with β-arrestins, and failed to promote sustained MAP kinase signaling. These findings suggest that the PAR2 C-tail regulates the stability of β-arrestin interaction and sustained MAP kinase signaling, but is not essential for rapid β-arrestin recruitment nor β-arrestin-dependent receptor desensitization or internalization. These findings further suggest that the diverse functions of β-arrestins in the regulation of PAR2 signaling and trafficking are likely to be controlled by distinct determinants. However, the PAR2-specific determinants that are critical for the diverse functions of β-arrestins in regulation of receptor signaling and trafficking remain poorly understood.

In the present study, we examine for the first time the role of phosphorylation in regulation of PAR2 signaling and trafficking. We report that phosphorylation of PAR2 distinctly regulates desensitization and endocytic trafficking. Our findings further demonstrate that PAR2 phosphorylation is critical for receptor desensitization and β-arrestin binding and that serine and threonine residues in the PAR2 C-tail domain impede constitutive internalization and lysosomal degradation. These studies reveal a novel function for phosphorylation in differentially regulating PAR2 desensitization and endocytic trafficking.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies

Agonist peptides TFLLRNPNDK (PAR1-specific) and SLIGKV (PAR2-specific) were synthesized as the carboxyl amide and purified by reverse-phase high-pressure chromatography (University of North Carolina Peptide Facility, Chapel Hill, NC). α-Trypsin treated with tosylamide-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone, leupeptin, and cycloheximide were from Sigma. [32P]Orthophosphate was purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Monoclonal M1 and M2 anti-FLAG, polyclonal anti-FLAG, and anti-β-actin antibodies were from Sigma. Anti-early endosome antigen-1 (EEA1) monoclonal antibody was purchased from BD Biosciences. Anti-clathrin monoclonal antibody X22 was from GeneTex, Inc. (San Antonio, TX). Anti-lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) H4A3 monoclonal antibody was from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA). Anti-β-arrestin polyclonal antibody A1CT was a gift from R. J. Lefkowitz (Duke University). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Alexa Fluor 488- and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit antibodies were from Invitrogen.

cDNAs and Cell Lines

A cDNA encoding the wild-type PAR2 containing an amino-terminal FLAG epitope was previously described (16). PAR2 mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using QuikChange (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), and mutations were confirmed by dideoxy sequencing. The PAR1 chimera containing the substance P receptor C-tail (P/S) was previously described (18). The green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged β-arrestin 1 and 2 constructs were a gift from M. Caron (Duke University). The GFP-tagged dynamin K44A mutant was a gift from M. McNiven (Mayo Clinic and Foundation).

HeLa cells and Rat1 fibroblasts were cultured as previously described (16, 18, 19). HeLa cells and Rat1 fibroblasts stably transfected with FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type and mutants were generated as previously published (18, 19).

siRNAs

HeLa cells were transiently transfected for 72 h with 100 nm nonspecific siRNA or smart pool siRNAs targeting the clathrin heavy chain or β-arrestin 1 and 2 using Lipofectamine 2000 or DharmaFECT 2 according to the manufacturer's protocol. All siRNAs were purchased from Dharmacon, Inc. (Lafayette, CO).

Phosphoinositide Hydrolysis

Cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type or mutants were plated at 0.8 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plates and grown overnight. Cells were labeled with 1 μCi/ml of myo-[3H]inositol (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) in serum- and inositol-free DMEM containing 1 mg/ml of BSA overnight. [3H]Inositol phosphates (IPs) were measured as previously described (20).

Receptor Immunoprecipitation, Phosphorylation, and Immunoblot Analysis

Rat1 fibroblasts stably expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type or mutants were plated at 3.5 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates and grown for 48 h. Cells were labeled with 200 μCi of [32P]orthophosphate in phosphate-free DMEM containing 1 mg/ml BSA for 3 h, washed, and incubated in the absence or presence of 100 μm SLIGKV diluted in DMEM containing 1 mg/ml of BSA and 10 mm HEPES for various times at 37 °C. Cells were lysed with Triton lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 50 mm sodium fluoride, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 200 mm sodium orthovanadate, and 1% Triton-X-100) containing protease inhibitors. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 anti-FLAG antibody, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to membranes. Phosphorylated receptor was detected by autoradiography. The amount of PAR2 in immunoprecipitates was determined by immunoblotting with polyclonal anti-FLAG antibody and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody.

HeLa cells stably transfected with FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type or mutants were plated at 1.5 × 106 cells/well in a 6-well plate and grown for 48 h at 37 °C. Cells were incubated for various times with or without 100 μm SLIGKV diluted in DMEM containing 10 μm cycloheximide, 1 mg/ml BSA, and 10 mm HEPES. Cells were lysed, immunoprecipitated, and immunoblotted as described above. Immunoblots were quantified using Image J software.

Cell Surface ELISA

Cells expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type or mutants were plated on fibronectin-coated 24-well plates and grown for 48 h. After incubations, cells were washed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The amount of cell surface receptor was quantitated by incubation with M1 anti-FLAG antibody at 25 °C for 1 h and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody at 25 °C for 1 h. The amount of bound secondary antibody was determined by incubating cells with 1-STEP ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (Pierce) for 10–20 min at 25 °C. An aliquot was taken to measure the optical density at 405 nm using a Molecular Devices microplate spectrophotometer.

Internalization Assay

Cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type or mutants were plated on fibronectin-coated 24-well plates and grown for 48 h. Cells were prelabeled with M1 anti-FLAG antibody for 1 h at 4 °C and then incubated with or without agonist for various times at 37 °C. The loss of cell surface receptor was measured by ELISA.

Immunofluorescence Confocal Microscopy

HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type or mutant were plated at 0.8 × 105 cells/well on fibronectin-coated glass coverslips in 12-well plates for 48 h at 37 °C. Cells were washed with ice-cold DMEM and prelabeled with polyclonal anti-FLAG antibody on ice for 1 h. Cells were incubated in the absence or presence of 100 μm SLIGKV for 30 min at 37 °C, washed, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were permeabilized with ice-cold 100% methanol and washed with phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% nonfat dry milk and 150 mm sodium acetate, pH 7.0. Cells were blocked with 1% nonfat dry milk in phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody. For LAMP1 co-localization studies, cells were incubated in DMEM containing 2 mm leupeptin, a lysosomal protease inhibitor, for 37 °C for 1 h. Cells were then processed as described above and immunostained for endogenous LAMP1, using a monoclonal anti-LAMP1 antibody for 1 h and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody. Cells were imaged by confocal microscopy as previously described (21, 22). For clathrin heavy chain knockdown experiments, endogenous clathrin was detected using anti-clathrin monoclonal antibody and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody.

Receptor Recycling

HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type or mutants were plated on fibronectin-coated 24- well plates and grown for 48 h at 37 °C. Cells were washed and incubated with calcium-dependent M1 anti-FLAG antibody diluted in DMEM containing 1 mg/ml of BSA, 1 mm CaCl2, and 10 mm HEPES for 1 h. Cells were incubated in the absence or presence of 100 μm SLIGKV for 60 min at 37 °C. Antibody-bound receptor remaining on the cell surface was stripped by washing with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.4% EDTA to chelate calcium. Cells were incubated for various times to allow recovery of antibody-bound receptor to the cell surface. Receptor recovery was measured by cell surface ELISA.

Data Analysis

Prism 3.0 software (GraphPad) was used to analyze the data and statistical significance was determined using InStat 3.0 (GraphPad). Statistical analysis was determined using one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's Multiple Comparison Test.

RESULTS

Phosphorylation of Activated PAR2 Occurs within the Cytoplasmic Tail

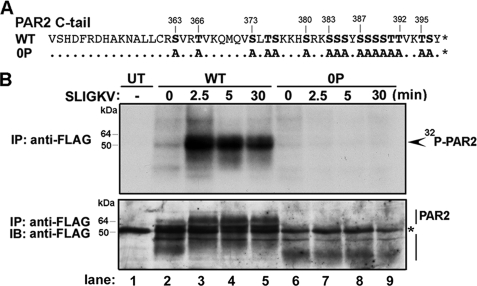

To determine the importance of phosphorylation in the regulation of PAR2 signaling and trafficking, we constructed a PAR2 mutant in which all serines (Ser) and threonines (Thr) in the C-tail region were mutated to alanines (Ala) (Fig. 1A). The PAR2 mutant was designated “PAR2 0P.” We first directly examined the time course of activated PAR2 phosphorylation. Rat1 fibroblasts stably expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type or 0P mutant labeled with [32P]orthophosphate were incubated in the absence or presence of saturating concentrations of the PAR2-specific agonist peptide SLIGKV for various times at 37 °C. PAR2 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates, and phosphorylation was analyzed by autoradiography. In the absence of agonist, a minimal amount of wild-type PAR2 phosphorylation was detected (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 2). This phosphorylation was not observed in untransfected cells and likely represents basal PAR2 phosphorylation. The addition of agonist induced a rapid and significant peak in activated PAR2 phosphorylation at 2.5 min, and phosphorylation of PAR2 remained elevated for 30 min in the continued presence of agonist (Fig. 1B, lanes 3–5). In contrast, the PAR2 mutant lacking all serines and threonines in the C-tail, designated PAR2 0P, showed little to no phosphorylation over the 30-min time course of agonist stimulation (Fig. 1B, lanes 6–9). Thus, agonist-induced rapid and sustained PAR2 phosphorylation predominantly within the C-tail domain.

FIGURE 1.

Agonist-induced phosphorylation of PAR2 occurs within the C-tail region. A, the PAR2 C-tail serines and threonines are shown in bold and were mutated to alanine to generate the PAR2 0P mutant. B, Rat1 fibroblasts stably expressing comparable amounts of FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type or 0P mutant labeled with [32P]orthophosphate were stimulated with 100 μm SLIGKV for various times at 37 °C. Equivalent amounts of cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with monoclonal M2 anti-FLAG antibody. Receptor immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography. No phosphorylated proteins were detected in immunoprecipitates from untransfected (UT) Rat1 fibroblasts. Membranes were then probed with a polyclonal anti-FLAG antibody to detect total PAR2. The asterisk indicates detection of a nonspecific FLAG-positive band in the UT lane, which is also detected in all PAR2 wild-type and PAR2 0P lanes. The initial amounts (mean ± S.D.; n = 3) of cell surface receptor expression measured by ELISA were 0.164 ± 0.033 and 0.112 ± 0.015 OD units for PAR2 wild-type (WT) and 0P mutant, respectively. IB, immunoblot.

Phosphorylation Mediates PAR2 Desensitization

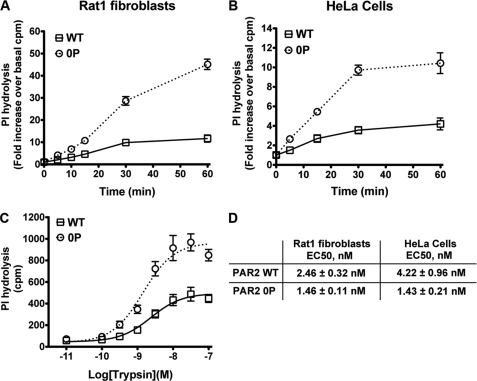

Agonist-induced phosphorylation and binding of β-arrestins mediate desensitization and internalization of many reversibly activated GPCRs (23). We previously showed that β-arrestins are essential for PAR2 desensitization (16); however, the contribution of phosphorylation to the termination of PAR2 signaling is not known. To test the importance of phosphorylation in PAR2 signal regulation we examined agonist-induced desensitization by quantitating the rate of IP accumulation. Activated PAR2 elicits phosphoinositide (PI) hydrolysis in multiple cell types (16, 24), an effect attributed to Gαq coupling to phospholipase C-β. We initially compared the rates of agonist-induced PI hydrolysis in Rat1 fibroblasts and HeLa cells stably expressing comparable amounts of PAR2 wild-type and phosphorylation-deficient 0P mutant on the cell surface. Cells were incubated with or without a saturating concentration of trypsin for various times at 37 °C, and total [3H]IPs were measured. After 60 min of agonist exposure, a marked ∼10-fold increase in PI hydrolysis was detected in wild-type PAR2 expressing Rat1 fibroblasts, whereas a substantially greater ∼40-fold increase in signaling was measured in cells expressing the phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant (Fig. 2A). Similarly, in HeLa cells, activation of phosphorylation-defective PAR2 0P mutant resulted in a ∼10-fold increase in PI hydrolysis, a response considerably more robust than that observed in cells expressing comparable amounts of wild-type PAR2 (Fig. 2B). In both PAR2 wild-type and 0P mutant expressing HeLa cells, stimulation of endogenous muscarinic acetylcholine receptors with carbachol resulted in comparable changes in PI hydrolysis, indicating that there are no cell clone-specific defects in G-protein signaling (data not shown). These data suggest that agonist-induced PAR2 phosphorylation is critical for termination of G protein signaling.

FIGURE 2.

Activated PAR2 phosphorylation is critical for desensitization. A, Rat1 fibroblasts, and B, HeLa cells stably expressing PAR2 wild-type (WT) and 0P mutant labeled with myo-[3H]inositol were incubated in the absence or presence of 10 nm trypsin for various times at 37 °C, and total [3H]IPs were measured. The data (mean ± S.E.; n = 3) shown are expressed as fold-increase over basal [3H]IPs and averaged over three independent experiments. C, the concentration effect curves of trypsin at PAR2 wild-type and the 0P mutant were determined in Rat1 fibroblasts. Cells labeled with myo-[3H]inositol were incubated with varying concentrations of trypsin for 10 min at 37 °C, and [3H]IPs were measured. The data (mean ± S.E.; n = 3) shown are averaged from three independent experiments. D, the effective concentrations of trypsin at PAR2 wild-type and the 0P mutant determined in Rat1 fibroblasts in C and in HeLa cells using the same experimental conditions. The data (mean EC50 ± S.E.; n = 3) are averaged from three separate experiments. The initial cell surface receptor expressions (mean ± S.D.; n = 3) measured by ELISA in HeLa cells were 0.253 ± 0.022 and 0.196 ± 0.023 OD units for PAR2 wild-type and the PAR2 0P mutant, respectively.

Next, we examined whether the initial coupling of activated PAR2 wild-type and 0P mutant to Gαq-promoted PI hydrolysis was affected. The concentration effect curves for trypsin at the PAR2 wild-type and phosphorylation-defective 0P mutant were determined by incubating cells labeled with myo-[3H]inositol and varying the concentrations of trypsin for 10 min at 37 °C, and accumulation of [3H]IPs was measured. The effective concentration of trypsin needed to stimulate a half-maximal response after 10 min was similar for both PAR2 wild-type and 0P mutant expressed in HeLa cells and significantly different in Rat1 fibroblasts (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2, C and D). Moreover, activation of the phosphorylation-defective PAR2 0P mutant caused an enhanced maximal signaling response compared with wild-type receptor (Fig. 2C) in Rat1 fibroblasts and HeLa cells (data not shown). These findings suggest that each activated PAR2 0P mutant coupled longer to PI hydrolysis before signaling was shut off, indicating a slower rate of desensitization.

To determine whether specific phosphorylation sites are important for regulation of PAR2 signaling a series of receptor mutants were constructed in which clusters of serines and threonines within the C-tail were replaced with alanines (Fig. 3A). PAR2 Ser/Thr cluster mutants were stably expressed in Rat1 fibroblasts, and agonist-promoted phosphorylation was determined. Wild-type PAR2 showed robust phosphorylation after 2.5 min of agonist activation, whereas phosphorylation of the PAR2 0P mutant lacking all C-tail serines and threonines was virtually abolished (Fig. 3B, lanes 1–4). Remarkably, activation of PAR2 Ser/Thr cluster mutants with SLIGKV for 2.5 min induced phosphorylation similar to that observed with wild-type PAR2 (Fig. 3B), suggesting that PAR2 phosphorylation occurs at multiple and/or redundant sites within the C-tail domain. To determine whether critical C-tail serine and threonine residues are important for desensitization, we examined agonist-stimulated PI hydrolysis in cells expressing PAR2 Ser/Thr cluster mutants (Fig. 3C). Rat1 fibroblasts expressing similar amounts of cell surface PAR2 wild-type, 0P, or Ser/Thr cluster mutants were incubated in the absence or presence of a saturating concentration of trypsin for 30 min at 37 °C, and total [3H]IPs were measured. All PAR2 Ser/Thr cluster mutants exhibited an increase in agonist-induced PI hydrolysis comparable with wild-type PAR2, whereas the phosphorylation-defective PAR2 0P mutant showed significantly enhanced signaling following agonist incubation. Taken together, these data suggest that multiple and/or redundant C-tail serine and threonine residues serve as critical sites for agonist-induced PAR2 phosphorylation and desensitization.

FIGURE 3.

Activated PAR2 exhibits multiple and/or redundant sites of phosphorylation. A, several PAR2 C-tail serine and threonine cluster mutants were generated by replacing specific Ser/Thr with alanines as depicted. Cluster mutants were designated as PAR2 S363/6A as previously described (16, 26) and C1–C5 for the remaining cluster mutants. B, Rat1 fibroblasts stably expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 WT, 0P, or Ser/Thr cluster mutants labeled with [32P]orthophosphate were incubated in the absence or presence of 100 μm SLIGKV for 2.5 min at 37 °C. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by autoradiography. The membranes were stripped and reprobed with polyclonal anti-FLAG antibody to detect total PAR2. C, Rat1 fibroblasts expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type, 0P, or Ser/Thr cluster mutants labeled with myo-[3H]inositol were incubated in the absence or presence of 10 nm trypsin for 60 min at 37 °C, and total [3H]IPs were measured. The data (mean ± S.E.; n = 3) are expressed as fold-increase over basal [3H]IPs and averaged from three independent experiments. A significant difference between PAR2 WT and PAR2 0P stimulated PI hydrolysis was detected (*, p < 0.05). The following are initial cell surface receptor amounts measured by ELISA (mean ± S.D.; n = 3): WT, 0.194 ± 0.027 OD units; 0P mutant, 0.138 ± 0.004 OD units; C1, 0.097 ± 0.013 OD units; C2, 0.136 ± 0.010 OD units; C3, 0.136 ± 0.010 OD units; C4, 0.08 ± 0.015 OD units; C5, 0.182 ± 0.004 OD units.

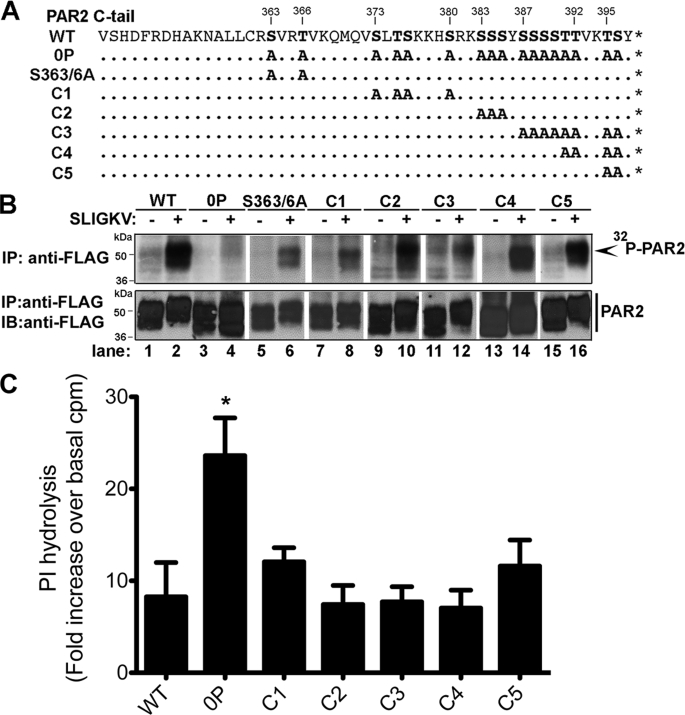

PAR2 0P Mutant Internalizes Constitutively

To determine the role of phosphorylation in PAR2 intracellular trafficking, we first examined constitutive and agonist-induced receptor internalization. Rat1 fibroblasts stably expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type or the phosphorylation-deficient 0P mutant were incubated with M1 anti-FLAG antibody at 4 °C. Under these conditions only receptors residing on the cell surface binds antibody. Cells were then incubated in the absence or presence of a saturating concentration of SLIGKV for various times at 37 °C, and the amount of receptor remaining on the cell surface was quantified by ELISA. In wild-type PAR2 expressing cells, agonist induced a rapid receptor internalization within 15 min, leading to a ∼70% loss of cell surface receptor after 60 min (Fig. 4A). The rate of agonist-induced internalization of the phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant was comparable with the wild-type receptor (Fig. 4A). We next examined constitutive internalization of wild-type PAR2 and observed a slow rate of internalization resulting in an ∼5–10% loss of cell surface receptor after 60 min (Fig. 4B). In striking contrast, phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant displayed an increased rate of constitutive internalization in which ∼65% of receptor was lost from the cell surface after 60 min (Fig. 4B). Similar findings were also observed in HeLa cells (data not shown). Immunofluorescence microscopy studies of HeLa cells are consistent with enhanced constitutive internalization of the phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant (Fig. 4C). HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type or 0P mutant were incubated in the absence or presence of agonist for 30 min at 37 °C, fixed, immunostained, and analyzed by confocal microscopy. A substantial amount of internalized phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant co-localized with EEA1, a marker of early endosomes in the presence and absence of agonist stimulation or antibody prebinding (Fig. 4C). In contrast, wild-type PAR2 localized predominantly to the cell surface in the absence of agonist (Fig. 4C), whereas activated PAR2 wild-type showed robust internalization and co-localization with EEA1 (Fig. 4C). To determine whether PAR2 internalization requires specific serine and threonine residues, we examined the rates of constitutive and agonist-induced internalization of PAR2 Ser/Thr cluster mutants (Fig. 4, D and E). Agonist-promoted PAR2 Ser/Thr cluster mutant internalization rates were comparable with wild-type PAR2 (Fig. 4D). Moreover, constitutive internalization rates of PAR2 wild-type and all Ser/Thr cluster mutants were similar, whereas the phosphorylation-defective PAR2 0P mutant displayed an enhanced rate of constitutive internalization (Fig. 4E). Collectively, these findings indicate that serines and threonines in the PAR2 C-tail prevent constitutive internalization and suggest that basal phosphorylation and/or a distinct conformation of the PAR2 C-tail regulates cell surface retention.

FIGURE 4.

Phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant constitutively internalizes. Rat1 fibroblasts stably expressing similar amounts of cell surface PAR2 wild-type (WT) or 0P mutant were incubated with M1 anti-FLAG antibody at 4 °C to label cell surface receptors. Cells were then incubated in medium with (A) or without (B) 100 μm SLIGKV for various times at 37 °C. Cells were fixed, and the amount of antibody-bound receptor remaining on the cell surface was quantitated by ELISA. The data are shown as the fraction of the initial M1 anti-FLAG antibody-bound receptor at time 0 min. The data (mean ± S.E.; n = 4) are averaged from four independent experiments. These cell lines were also used in analyzing PAR2 signaling, and initial cell surface receptor expression was reported in the legend to Fig. 1. C, HeLa cells expressing PAR2 wild-type or 0P mutant were incubated in the absence or presence of 100 μm SLIGKV for 30 min at 37 °C, fixed, permeabilized, and immunostained for PAR2 (green) using polyclonal anti-FLAG antibody and the early endosomal marker EEA1 (red) using monoclonal anti-EEA1 antibody. The cells were imaged by confocal microscopy. Co-localization of PAR2 with EEA1 is shown as yellow in the merged image. The initial cell surface receptor expression in HeLa cells was the same as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Scale bar, 10 μm. D and E, Rat1 fibroblasts expressing PAR2 wild-type, PAR2 0P mutant, or PAR2 Ser/Thr cluster mutants were examined for receptor internalization as described above with (D) or without (E) 100 μm SLIGKV for various times. The data (mean ± S.E.; n = 4) shown are averaged from four separate experiments. Initial cell surface expression was determined by ELISA and reported in the legend to Fig. 3.

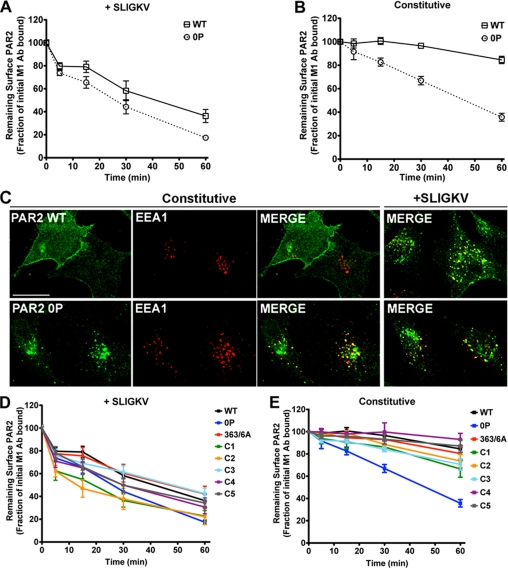

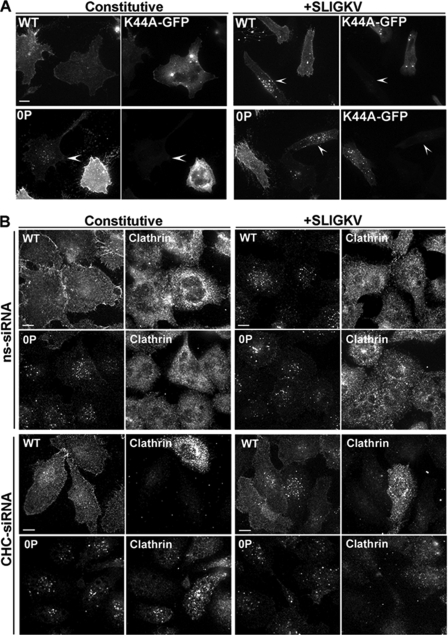

We next examined whether the phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant internalized through a dynamin-dependent pathway like wild-type PAR2 (25). HeLa cells expressing PAR2 wild-type or 0P mutant were transiently transfected with GFP-tagged dynamin K44A mutant, and receptor internalization was examined by immunofluorescence microscopy. Constitutive internalization of a phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant was substantially inhibited in dynamin K44A mutant expressing cells, which showed more receptor retained on the cell surface compared with adjacent cells not expressing dynamin K44A (Fig. 5A). Indeed, in cells lacking dynamin K44A expression, the PAR2 0P mutant localized predominantly to endosomes and not at the cell surface (Fig. 5A, arrowhead). Internalization of activated PAR2 wild-type and 0P mutant were also markedly inhibited in dynamin K44A mutant expressing cells, which displayed more cell surface-localized PAR2 than adjacent untransfected cells (Fig. 5A, arrowheads). These findings suggest that internalization of phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant is mediated by dynamin similar to the wild-type receptor.

FIGURE 5.

Constitutive internalization of PAR2 0P mutant requires dynamin but not clathrin. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type or 0P mutant and GFP-tagged dynamin K44A (see Fig. 2 for initial cell surface receptor expression). A, cells were labeled with M1 monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody for 1 h at 4 °C and stimulated with or without 100 μm SLIGKV for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were fixed, processed, and imaged by confocal microscopy. In GFP-tagged dynamin K44A expressing cells, PAR2 wild-type and 0P endocytosis was inhibited, whereas in cells lacking dynamin K44A, receptor internalization was partially impaired (arrowheads). B, HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type (WT) or 0P were transiently transfected with clathrin heavy chain (CHC) or nonspecific (ns) siRNA for 72 h. Cells were labeled with M1 monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody for 1 h at 4 °C and then stimulated with or without 100 μm SLIGKV for 30 min at 37 °C. The images shown are representative of at least three separate experiments. Cells were fixed and processed for confocal microscopy. Cells depleted of endogenous clathrin were immunostained using anti-clathrin monoclonal antibody ×22. Scale bar, 10 μm.

To determine the role of clathrin in phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant internalization, we used siRNA targeting endogenous clathrin heavy chain as previously described (22). The expression of clathrin heavy chain was substantially reduced in cells transiently transfected with siRNA specifically targeting clathrin compared with nonspecific siRNA control as detected by immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5B, bottom panels). In cells lacking clathrin expression, activated PAR2 wild-type internalization was considerably impaired with more receptor retained at the cell surface compared with adjacent untransfected cells or cells transfected with nonspecific control siRNA (Fig. 5B). In striking contrast, constitutive and agonist-induced internalization of phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant occurred regardless of clathrin heavy chain expression (Fig. 5B). Thus, unlike the wild-type receptor, phosphorylation-defective PAR2 0P mutant internalization occurs through a clathrin-independent pathway.

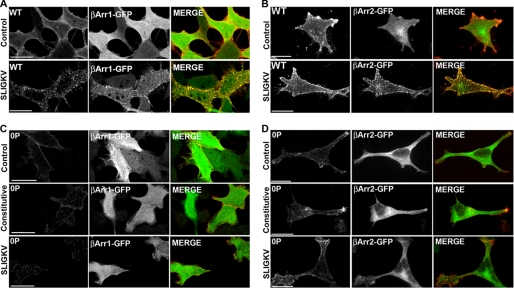

We previously reported that β-arrestins are rapidly recruited to activated PAR2 and are essential for agonist-promoted receptor internalization (16). To assess the importance of β-arrestins in phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant internalization, we initially examined β-arrestin-1-GFP and β-arrestin-2-GFP redistribution following the addition of agonist. In untreated PAR2 wild-type expressing cells, β-arrestin-1-GFP and β-arrestin-2-GFP remained distributed throughout the cytoplasm, whereas stimulation with the agonist peptide SLIGKV for 5 min resulted in β-arrestin-GFP rapid redistribution and co-localization with PAR2 wild-type (Fig. 6, A and B). In contrast, β-arrestin-1-GFP and β-arrestin-2-GFP were not recruited to the cell surface in phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant expressing cells but remained cytosolic under control, constitutive, and agonist-induced conditions (Fig. 6, C and D).

FIGURE 6.

PAR2 0P mutant fails to induce β-arrestin-1 or -2-GFP translocation. HeLa cells expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type (WT) (A, B) or 0P mutant (C, D) were transiently transfected with β-arrestin 1-GFP (A, C) or β-arrestin 2-GFP (B, D). Cells were labeled with M1 monoclonal anti-mouse antibody for 1 h at 4 °C before incubating in the absence or presence of 100 μm SLIGKV for 5 min at 37 °C. Cells were fixed and processed for confocal microscopy. Control cells were prelabeled with M1 monoclonal anti-mouse antibody and immediately fixed and processed for confocal microscopy. Control images show cytosolic β-arrestin-1-GFP and β-arrestin-2-GFP before stimulation. Images of cells are representative of three independent experiments. Scale bar, 10 μm.

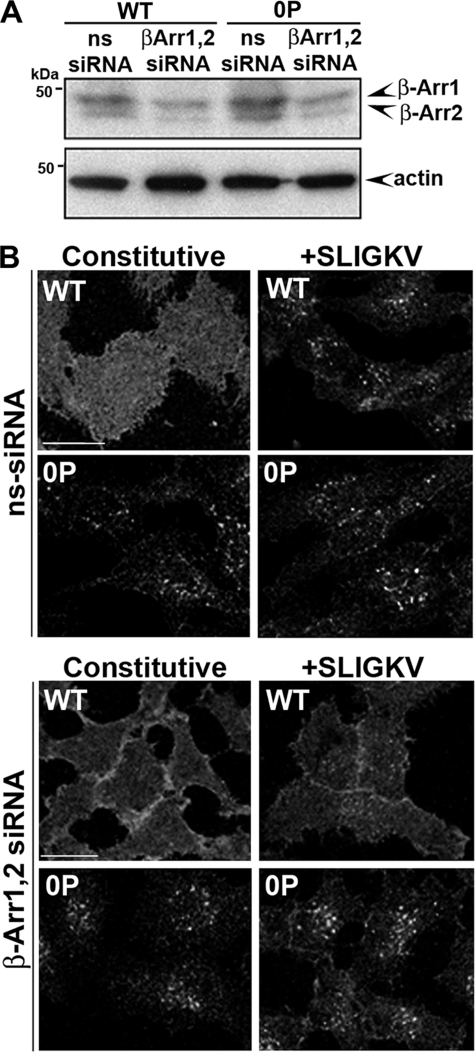

Previous studies have demonstrated that β-arrestins were essential for wild-type PAR2 internalization (16, 26). To examine the function of β-arrestins in phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant internalization, we transfected HeLa cells with siRNAs targeting endogenous β-arrestin 1 and 2. Immunoblot analysis showed a significant reduction in β-arrestin 1 and 2 protein expression in cells transfected with siRNAs targeting β-arrestins compared with nonspecific siRNA control cells (Fig. 7A). Similar to previous results in β-arrestin 1 and 2 null mouse embryonic fibroblasts, PAR2 wild-type failed to internalize in cells depleted of β-arrestins (Fig. 7B) (16). In contrast, loss of β-arrestin 1 and 2 had no effect on constitutive or agonist-induced internalization of the phosphorylation-defective PAR2 0P mutant (Fig. 7B). These findings suggest that β-arrestins are not essential for phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant internalization.

FIGURE 7.

Constitutive internalization of PAR2 0P mutant occurs independent of β-arrestins. A, HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type (WT) or 0P were transiently transfected with β-arrestin 1 and 2 or nonspecific siRNAs for 72 h. The depletion of β-arrestin 1 and 2 expression was determined by immunoblot analysis using polyclonal anti-β-arrestin antibody A1CT. Membranes were stripped and reprobed with an anti-actin antibody as a control for loading. The initial cell surface receptor expression in HeLa cells was reported as described in the legend to Fig. 2. B, cells were labeled with polyclonal anti-FLAG antibody for 1 h at 4 °C. Cells were then treated with or without 100 μm SLIGKV for 30 min at 37 °C and processed for confocal microscopy. Confocal microscopy images are representative of results from three independent experiments. Scale bar, 10 μm.

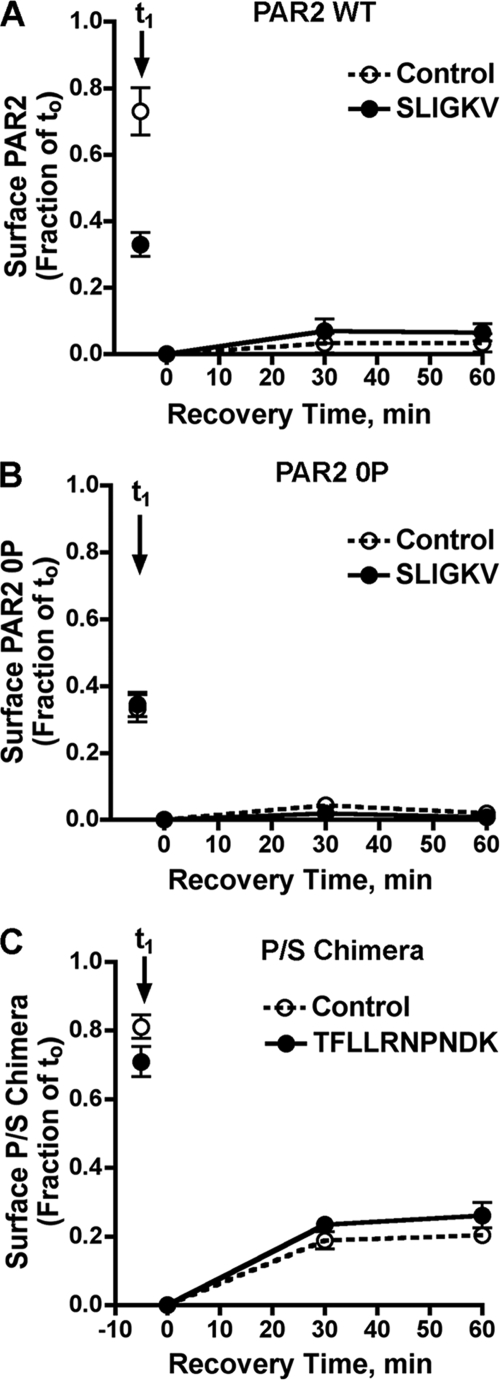

The Phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P Mutant Constitutively Sorts to Lysosomes and Degrades and Does Not Recycle to the Cell Surface

The increased accumulation of intracellular phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant observed in the absence of agonist may result from an increased rate of constitutive internalization and/or an inability of the mutant receptor to recycle or sort to lysosomes for degradation. We therefore examined internalization and recycling of phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant. HeLa cells expressing FLAG-PAR2 wild-type or 0P mutant were incubated with calcium-dependent M1 anti-FLAG antibody at 4 °C to label cell surface receptors and then stimulated with or without agonist for 60 min at 37 °C. In the absence of agonist, PAR2 wild-type showed a modest loss of cell surface receptor after 60 min of incubation at 37 °C (t1), whereas agonist addition resulted in an ∼70% decrease in the level of PAR2-bound antibody on the cell surface (Fig. 8A). In contrast, phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant expressing cells not exposed to agonist during the 60-min incubation showed ∼70% internalization (t1) (Fig. 8B), consistent with enhanced constitutive internalization. Exposure to agonist peptide SLIGKV during the 60-min incubation caused a similar ∼70–80% decrease in cell surface PAR2 0P mutant (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant constitutively internalizes and does not recycle. HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type (WT) (A), 0P mutant (B), or the P/S chimera (C) were labeled with M1 monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody for 1 h at 4 °C (see Fig. 2 legend for initial cell surface receptor expression). At t0, cells were washed to remove unbound antibody and stimulated with or without 100 μm SLIGKV (PAR2-specific) or 100 μm TFLLRNPNDK (PAR1-specific) for 60 min at 37 °C. After the initial incubation, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline/EDTA to strip away any antibody-bound receptor remaining on the cell surface and were then warmed for various times at 37 °C to allow previously internalized receptor to recover to the cell surface. Cells were then fixed and recovery of antibody-bound receptor was quantitated by ELISA. The data (mean ± S.D.; n = 3) are represented as a fraction of total M1 antibody bound at time t0, and are from one experiment representative of three independent experiments.

After initial incubation with or without agonist, antibody was stripped from the cell surface and recovery of previously internalized receptor-bound antibody was measured at various times. In PAR2 wild-type expressing cells, little recovery of antibody was observed in cells irrespective of agonist incubation (Fig. 8A). Similarly, in phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant-expressing cells incubated in the absence or presence of agonist, there was minimal recovery of internalized antibody despite the large cohort of receptor-bound antibody that had been previously internalized (Fig. 8B). In contrast to PAR2, a chimeric PAR1 bearing the cytoplasmic tail of the substance P receptor (P/S C-tail) pretreated with the PAR1-specific agonist peptide TFLLRNPNDK showed substantial recovery of antibody on the cell surface with time (Fig. 8C), consistent with its internalization and recycling as previously reported (18). These data are consistent with an enhanced rate of phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant internalization and suggest a novel function for phosphorylation in negative regulation of PAR2 internalization.

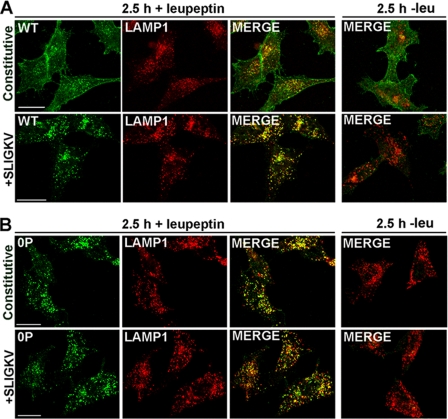

To directly test whether the phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant constitutively sorts to lysosomes, we used confocal microscopy to assess whether receptors sort to a LAMP1-positive compartment. LAMP1 is a specific marker of late endosomes and lysosomes. HeLa cells expressing PAR2 wild-type or 0P mutant were pretreated with or without leupeptin, a lysosomal protease inhibitor, and incubated in the absence or presence of the peptide agonist SLIGKV for 2.5 h at 37 °C. In the absence of agonist, PAR2 wild-type localized predominantly to the surface of cells treated with or without leupeptin (Fig. 9A). After prolonged agonist exposure, PAR2 was no longer detectable in control cells (Fig. 9A), whereas cells pretreated with leupeptin showed a significant accumulation of receptor in vesicles that co-stained for LAMP1 (Fig. 9A). These findings are consistent with agonist-induced internalization and lysosomal degradation of wild-type PAR2. In the absence of leupeptin, little co-localization of phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant and LAMP1 was observed in agonist-treated or untreated cells (Fig. 9B), suggesting that internalized PAR2 0P mutant is sorted to lysosomes and rapidly degraded. In contrast to wild-type PAR2, however, unactivated PAR2 0P mutant was found largely in LAMP1-positive vesicles in cells pretreated with leupeptin (Fig. 9B). Similarly, activated PAR2 0P mutant also localized predominantly to vesicles that co-localized with LAMP1 after prolonged agonist exposure in leupeptin-treated cells (Fig. 9B). These results suggest that the phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant undergoes constitutive internalization and sorts from endosomes to lysosomes independent of phosphorylation.

FIGURE 9.

Co-localization of PAR2 wild-type and 0P mutant with LAMP1. HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type (WT) or 0P mutant were pre-treated with or without 2 mm leupeptin for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were incubated with polyclonal anti-FLAG antibody for 1 h at 4 °C to label cell surface receptors and then incubated in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 100 μm SLIGKV for 2.5 h at 37 °C. Cells were fixed, processed, and immunostained for PAR2 (green) and LAMP1 (red) and imaged by confocal microscopy. Co-localization of PAR2 with LAMP1 is shown as yellow in the merged imaged, and the cells shown are representative of many cells visualized in three independent experiments. Scale bar, 10 μm.

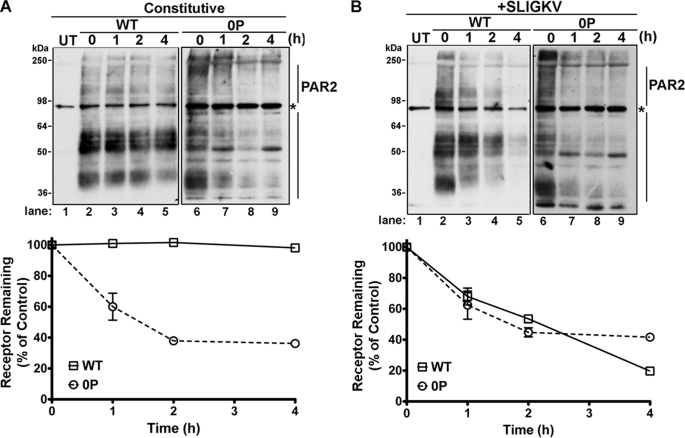

We next directly compared the rates of PAR2 wild-type and phosphorylation-deficient 0P mutant degradation. HeLa cells expressing PAR2 wild-type or 0P mutant were incubated with or without agonist for various times at 37 °C, and the amount of receptor protein remaining was determined by immunoblot analysis. PAR2 wild-type expressing cells not exposed to agonist showed a modest basal turnover when de novo receptor synthesis was inhibited with cycloheximide (Fig. 10A). The majority of PAR2 species migrated between ∼36 and ∼64 kDa, whereas higher molecular mass species are probably due to N-linked glycosylation and/or ubiquitination as previously reported (27, 28). In cells exposed to the agonist peptide SLIGKV for 2 h, a significant decrease in the amount of PAR2 wild-type protein was observed and the receptor protein was virtually abolished after 4 h of agonist exposure (Fig. 10B, lanes 2–5). Interestingly, unlike wild-type receptor, unactivated phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant protein was markedly decreased in the presence of cycloheximide and was comparable with that observed in agonist-treated cells (Fig. 10, A and B). These findings are consistent with constitutive internalization and lysosomal degradation of phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant.

FIGURE 10.

Phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant is constitutively sorted to lysosomes and degraded. HeLa cells expressing FLAG-tagged PAR2 wild-type (WT) (A) or 0P mutant (B) were incubated with or without 100 μm SLIGKV for various times at 37 °C in the presence of 10 μm cycloheximide to prevent new receptor synthesis. Equivalent amounts of cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 anti-FLAG antibody, and the amount of PAR2 remaining was detected by immunoblot analysis. Untransfected (UT) HeLa cells are shown in the adjacent lanes. The asterisk indicates detection of a nonspecific FLAG-positive band in the UT lane, which is also detected in all PAR2 wild-type and PAR2 0P lanes. Immunoblot data (mean ± S.E.; n = 2) was quantified using Image J software and plotted as a fraction of untreated control cells.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrate that PAR2 signaling and endocytic trafficking are differentially regulated by phosphorylation. The PAR2 C-tail contains multiple serine and threonine residues that could serve as potential phosphorylation sites for GRKs or second messenger protein kinases. Previous studies showed that pharmacological inhibitors of protein kinase C enhance PAR2-mediated calcium responses in KNRK and hBRIE 380 cells, suggesting a role for protein kinase C in PAR2 desensitization (24). However, whether PAR2 is directly modified by phosphorylation and the function of such phosphorylation in regulation of PAR2 signaling and trafficking remains to be determined. We report here that activated PAR2 phosphorylation is critical for receptor desensitization and β-arrestin recruitment. We found that PAR2 internalization can proceed independent of G-protein activation and phosphorylation. These studies suggest that phosphorylation and/or a distinct conformation of PAR2 is essential for retaining the receptor at the cell surface. We further show that the phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant internalizes constitutively and sorts to lysosomes through a dynamin-dependent but clathrin- and β-arrestin-independent pathway. Together these studies suggest that PAR2 internalization can be uncoupled from G-protein activation and phosphorylation, indicating that distinct determinants control the capacity of PAR2 to signal versus recruitment of β-arrestin and endocytosis.

The mechanisms controlling GPCR desensitization are best characterized for the photoreceptor rhodopsin and β2-adrenergic receptor (11). In this classic model, ligand-activated receptors are rapidly phosphorylated at multiple intracellular serine and threonine residues by GRKs. Phosphorylation enhances binding of β-arrestins, which sterically hinders receptor interactions with G-proteins. Thus, phosphorylation and β-arrestin binding function together to uncouple the receptor from G-protein activation and thus, promote signal termination. We observed a similar mechanism of desensitization for PAR2 in which the phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant exhibited a slowed rate of desensitization, suggesting a defect in uncoupling from G-protein signaling. Moreover, we previously showed that PAR2 desensitization is severely impaired in β-arrestin 1 and 2 null mouse embryonic fibroblasts, indicating that phosphorylation and β-arrestin binding are critical for definitively shutting-off PAR2 signaling (16).

Most activated and phosphorylated GPCRs bind to β-arrestins, which facilitates receptor recruitment to clathrin-coated pits and endocytosis. We previously showed that internalization of wild-type PAR2 is critically dependent on β-arrestins (16), like most classic GPCRs. In the present study, we found that the phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant was capable of internalization independent of β-arrestins. Interestingly, in the absence of agonist, the PAR2 0P mutant displayed enhanced endocytosis, whereas unactivated PAR2 wild-type and Ser/Thr cluster mutants remained at the cell surface. In addition, constitutive and agonist-induced phosphorylation-defective PAR2 0P mutant internalization occurred normally in β-arrestin 1 and 2 siRNA-depleted cells. In contrast, siRNA-targeted depletion of β-arrestins virtually ablated agonist-induced wild-type PAR2 internalization, consistent with our previous findings in which wild-type PAR2 internalization was completely abolished in β-arrestin 1 and 2 null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (16). Collectively, these findings suggest that phosphorylation of PAR2 is critical for specifying β-arrestin recruitment but is dispensable for receptor internalization. Thus, phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P has the capacity to engage the endocytic machinery and internalizes independent of β-arrestins even in the absence of agonist.

Similar to PAR2, previous studies have shown that phosphorylation is not required for agonist-induced internalization of CXCR4 or the δ-opioid receptor (29, 30). β-Arrestins are also dispensable for internalization of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, PAR1, and the formyl peptide receptor (20, 31, 32). Studies of the m2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor identified a Ser/Thr cluster mutant that displayed impaired desensitization of adenylyl cyclase signaling and binding to β-arrestins (33, 34), similar to the phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant. In addition, this m2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor Ser/Thr cluster mutant internalized like wild-type receptor in human embryonic kidney 293 cells, and overexpression of β-arrestin 1 or β-arrestin 2 had no effect on its internalization. The authors concluded that m2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor predominantly uses an β-arrestin-independent pathway for receptor internalization and that phosphorylation may regulate both β-arrestin-dependent and β-arrestin-independent activities (33). In the case of PAR1, unactivated receptor internalizes constitutively through clathrin-coated pits independent of phosphorylation and β-arrestin binding. Rather than β-arrestins, PAR1 constitutive endocytosis is mediated by adaptor protein complex-2, in which the μ2-subunit binds directly to a distal tyrosine-based motif within the receptor C-tail (35). The adaptor protein that mediates constitutive internalization of the phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant is not known. Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that mutating the PAR2 C-tail disrupts a conformation of the receptor important for cell surface retention and/or receptor endocytosis. Thus, our results suggest that phosphorylation and/or a distinct conformation of the C-tail domain of PAR2 are critical for negatively regulating receptor internalization and specifying endocytosis through an β-arrestin-dependent pathway.

PAR2 appears to internalize through a dynamin-dependent but clathrin- and β-arrestin-independent pathway in the absence of phosphorylation. Most classic GPCRs bind β-arrestins, which engages adaptor protein complex-2 and the clathrin heavy chain to promote receptor internalization through a dynamin- and clathrin-dependent pathway; however, some GPCRs utilize a dynamin-dependent but clathrin-independent mode of endocytosis (36). Clathrin-independent endocytosis can occur through lipid rafts, membrane microdomains that are highly enriched in cholesterol and glycosphingolipids (37). A distinct subset of lipid rafts known as caveolae form flask-shaped pits at the plasma membrane and are enriched in the structural scaffolding protein caveolin. Caveolin is thought to sequester membrane proteins, including GPCRs, into caveolae through protein-protein interactions with caveolin binding motifs. We have identified a putative caveolin-binding motif within the carboxyl-terminal portion of the seventh transmembrane domain of PAR2 (YXFVSHDF, ϕXϕXXXXϕ), which may confer an interaction with caveolin to facilitate movement into caveolar membranes and endocytosis. Indeed, in MDA-MB-231 cells, a fraction of PAR2 is present in caveolin-1 positive and detergent-resistant lipid fractions and co-localizes with caveolin-1 as assessed by immunofluorescence microscopy (38). However, whether PAR2 and caveolin-1 directly interact has not been determined. The phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant may also utilize other clathrin-independent modes of endocytosis via non-caveolar pathways. In lymphocytes deficient in caveolin-1, the interleukin-2 receptor partitioned into detergent-resistant fractions and internalized through a clathrin-independent but dynamin- and RhoA-dependent pathway (39). It is unclear, however, whether RhoA activity mediates PAR2 redistribution into lipid rafts and/or facilitates receptor endocytosis.

Our studies further suggest that internalized PAR2 can sort from endosomes to lysosomes in the absence of receptor activation and phosphorylation. The β2-adrenergic receptor and CXCR4 traffic from endosomes to lysosomes through a ubiquitin-dependent pathway (40, 41). Ubiquitinated cargo interacts with the ubiquitin binding motif of hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (HRS) (42). HRS associates with early endosomal membranes and sorts ubiquitinated proteins from early endosomes to late endosomes. HRS also directly binds to tumor suppressor gene product 101 (Tsg101) of the ESCRT complex, which is required for multivesicular body formation, lysosomal fusion, and subsequent degradation of proteins and lipids. A recent study showed that activated PAR2 is ubiquitinated by the E3 ligase Cbl, and a receptor mutant that is not ubiquitinated fails to degrade in the presence of agonist (27). In addition, post-endocytic sorting of PAR2 requires HRS, but the role of Tsg101 and other members of the ESCRT machinery is currently unknown (43). In contrast to wild-type PAR2, the δ-opioid receptor and PAR1 sort to lysosomes independent of ubiquitination (44, 45). Interestingly, δ-opioid receptor still requires HRS for lysosomal sorting, suggesting alternative sorting mechanisms of HRS for non-ubiquitinated cargo (46). PAR1 sorts to lysosomes independent of HRS and Tsg101 but requires SNX1, a protein that functions in vesicular trafficking (21). Whether phosphorylation-deficient PAR2 0P mutant is ubiquitinated and sorts to lysosomes through an ESCRT-dependent or -independent pathway remains to be determined.

Together our studies reveal a novel function for phosphorylation that differentially regulates PAR2 signaling and trafficking. However, whether GRKs or second messenger kinases phosphorylate PAR2 at distinct sites to differentially regulate PAR2 signaling and trafficking is not known and an important future pursuit. Moreover, the role of PAR2 phosphorylation in possibly regulating distinct functions of β-arrestins warrants further investigation. The binding of β-arrestins to activated and phosphorylated GPCRs appears to be independent of a consensus sequence or phosphorylation-specific sites; however, recent studies suggest that phosphorylation by specific GRKs can have differential effects on β-arrestin function (47). The depletion of GRK2 by siRNA knockdown reduced V2 vasopressin and AT1A angiotensin receptor phosphorylation and inhibited receptor internalization and desensitization, whereas loss of GRK 5/6 only prevented prolonged MAPK activation (48, 49). Thus, it is possible that β-arrestins form a different active conformation when bound to GRK2- versus GRK5/6-phosphorylation sites and in turn, confer different β-arrestin-mediated functions (47). Thus far, we have been unable to identify specific phosphorylation sites in PAR2 that might differentially regulate β-arrestin function, suggesting that other determinants may also contribute to the diverse regulatory mechanisms that control PAR2 signaling and trafficking.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the T. K. Harden, R. Nicholas, and J. Trejo laboratories for comments and helpful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant HL073328 (to J. T.) and an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award (to J. T.).

- PAR

- protease-activated receptor

- C-tail

- cytoplasmic tail

- EEA1

- early endosomal antigen-1

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- GRK

- G protein-coupled receptor kinase

- IP

- inositol phosphate

- LAMP1

- lysosomal-associated membrane protein-1

- PI

- phosphoinositide

- HRS

- hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arora P., Ricks T. K., Trejo J. (2007) J. Cell Sci. 120, 921–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ge L., Shenoy S. K., Lefkowitz R. J., DeFea K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55419–55424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris D. R., Ding Y., Ricks T. K., Gullapalli A., Wolfe B. L., Trejo J. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 307–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohm S. K., Kong W., Bromme D., Smeekens S. P., Anderson D. C., Connolly A., Kahn M., Nelken N. A., Coughlin S. R., Payan D. G., Bunnett N. W. (1996) Biochem. J. 314, 1009–1016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camerer E., Huang W., Coughlin S. R. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 5255–5260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Déry O., Thoma M. S., Wong H., Grady E. F., Bunnett N. W. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 18524–18535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nystedt S., Emilsson K., Wahlestedt C., Sundelin J. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 9208–9212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ge L., Ly Y., Hollenberg M., DeFea K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 34418–34426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacob C., Yang P. C., Darmoul D., Amadesi S., Saito T., Cottrell G. S., Coelho A. M., Singh P., Grady E. F., Perdue M., Bunnett N. W. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 31936–31948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zoudilova M., Kumar P., Ge L., Wang P., Bokoch G. M., DeFea K. A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20634–20646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitcher J. A., Freedman N. J., Lefkowitz R. J. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 653–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferguson S. S., Downey W. E., 3rd, Colapietro A. M., Barak L. S., Ménard L., Caron M. G. (1996) Science 271, 363–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodman O. B., Jr., Krupnick J. G., Santini F., Gurevich V. V., Penn R. B., Gagnon A. W., Keen J. H., Benovic J. L. (1996) Nature 383, 447–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laporte S. A., Oakley R. H., Zhang J., Holt J. A., Ferguson S. S., Caron M. G., Barak L. S. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 3712–3717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luttrell L. M. (2003) J. Mol. Endocrinol. 30, 117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stalheim L., Ding Y., Gullapalli A., Paing M. M., Wolfe B. L., Morris D. R., Trejo J. (2005) Mol. Pharmacol. 67, 78–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurevich V. V., Gurevich E. V. (2006) Pharmacol. Ther. 110, 465–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trejo J., Coughlin S. R. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 2216–2224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trejo J., Altschuler Y., Fu H. W., Mostov K. E., Coughlin S. R. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31255–31265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paing M. M., Stutts A. B., Kohout T. A., Lefkowitz R. J., Trejo J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1292–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gullapalli A., Wolfe B. L., Griffin C. T., Magnuson T., Trejo J. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 1228–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfe B. L., Marchese A., Trejo J. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 177, 905–916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krupnick J. G., Benovic J. L. (1998) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 38, 289–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Böhm S. K., Khitin L. M., Grady E. F., Aponte G., Payan D. G., Bunnett N. W. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 22003–22016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roosterman D., Schmidlin F., Bunnett N. W. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 284, C1319–C1329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeFea K. A., Zalevsky J., Thoma M. S., Déry O., Mullins R. D., Bunnett N. W. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 148, 1267–1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacob C., Cottrell G. S., Gehringer D., Schmidlin F., Grady E. F., Bunnett N. W. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16076–16087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Compton S. J., Sandhu S., Wijesuriya S. J., Hollenberg M. D. (2002) Biochem. J. 368, 495–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haribabu B., Richardson R. M., Fisher I., Sozzani S., Peiper S. C., Horuk R., Ali H., Snyderman R. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 28726–28731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray S. R., Evans C. J., von Zastrow M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 24987–24991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vines C. M., Revankar C. M., Maestas D. C., LaRusch L. L., Cimino D. F., Kohout T. A., Lefkowitz R. J., Prossnitz E. R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41581–41584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee K. B., Pals-Rylaarsdam R., Benovic J. L., Hosey M. M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 12967–12972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pals-Rylaarsdam R., Gurevich V. V., Lee K. B., Ptasienski J. A., Benovic J. L., Hosey M. M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 23682–23689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pals-Rylaarsdam R., Hosey M. M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 14152–14158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paing M. M., Johnston C. A., Siderovski D. P., Trejo J. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 3231–3242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marchese A., Paing M. M., Temple B. R., Trejo J. (2008) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 48, 601–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayor S., Pagano R. E. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 603–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Awasthi V., Mandal S. K., Papanna V., Rao L. V., Pendurthi U. R. (2007) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 1447–1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamaze C., Dujeancourt A., Baba T., Lo C. G., Benmerah A., Dautry-Varsat A. (2001) Mol. Cell 7, 661–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marchese A., Benovic J. L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 45509–45512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shenoy S. K., McDonald P. H., Kohout T. A., Lefkowitz R. J. (2001) Science 294, 1307–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchese A., Raiborg C., Santini F., Keen J. H., Stenmark H., Benovic J. L. (2003) Dev. Cell 5, 709–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hasdemir B., Bunnett N. W., Cottrell G. S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 29646–29657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanowitz M., Von Zastrow M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 50219–50222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolfe B. L., Trejo J. (2007) Traffic 8, 462–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whistler J. L., Enquist J., Marley A., Fong J., Gladher F., Tsuruda P., Murray S. R., Von Zastrow M. (2002) Science 297, 615–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tobin A. B. (2008) Br. J. Pharmacol. 153, Suppl. 1, S167–S176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim J., Ahn S., Ren X. R., Whalen E. J., Reiter E., Wei H., Lefkowitz R. J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 1442–1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ren X. R., Reiter E., Ahn S., Kim J., Chen W., Lefkowitz R. J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 1448–1453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]