Abstract

The ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation pathway is increasingly being recognized as important in regulation of protein turnover in eukaryotic cells. One substrate of this pathway is the pyrimidine biosynthetic enzyme thymidylate synthase (TS; EC 2.1.1.45), which catalyzes the reductive methylation of dUMP to form dTMP and is essential for DNA replication during cell growth and proliferation. Previous work from our laboratory showed that degradation of TS is ubiquitin-independent and mediated by an intrinsically disordered 27-residue region at the N-terminal end of the molecule. In the current study we show that this region, in cooperation with an α-helix formed by the next 15 residues, functions as a degron, i.e. it is capable of destabilizing a heterologous protein to which it is fused. Comparative analysis of the primary sequence of TS from a number of mammalian species revealed that the N-terminal domain is hypervariable among species yet is conserved with regard to its disordered nature, its high Pro content, and the occurrence of Pro at the penultimate site. Characterization of mutant proteins showed that Pro-2 protects the N terminus against Nα-acetylation, a post-translational process that inhibits TS degradation. However, although a free amino group at the N terminus is necessary, it is not sufficient for degradation of the polypeptide. The implications of these findings to the proteasome-targeting function of the N-terminal domain, particularly with regard to its intrinsic flexibility, are discussed.

Introduction

Regulated protein degradation within the cell is carried out primarily by the 26 S proteasome, a large 2-MDa complex consisting of several dozen proteins that function in recognizing and degrading its target substrates (1, 2). Typically, covalent attachment of polyubiquitin chains serves as the primary signal for target recognition by the proteasome (1, 2). However, in recent years several proteasomal substrates have been shown to be degraded without a requirement for ubiquitin modification (for a recent review, see Ref. 3). Such substrates include ornithine decarboxylase (ODC)3 (4–6), c-Fos (7, 8), p21Cip1 (9, 10), hepatitis virus F protein (11), and c-Jun (12), among others. Although the number of substrates identified as degraded by a ubiquitin-independent mechanism remains small, recent biochemical analyses indicate that the process may be more widespread than previously thought and contributes significantly to the regulation of protein turnover (13).

Among the known substrates of the ubiquitin-independent degradation pathway, ODC has been the most studied. The degradation signal for ODC is composed of a disordered, flexible domain formed by a 37-residue region at the C terminus (4–6). The region mediates docking of the ODC polypeptide to the proteasome and initiates its entry into the proteasomal chamber, where proteolysis proceeds in a C- to N-terminal direction (4–6). This process is stimulated by an accessory protein termed antizyme, which binds ODC and increases the availability of its C-terminal end (6). Although a significant amount of information has been obtained on ODC and other proteins that are degraded in a ubiquitin-independent manner, the detailed mechanisms by which these substrates are recognized by the proteasome and subjected to proteolytic breakdown remain unknown.

Another protein that is a model of ubiquitin-independent degradation is thymidylate synthase (TS; EC 2.1.1.45). TS catalyzes the reductive methylation of dUMP by N5N10-methylenetetrahydrofolate, generating dTMP and dihydrofolate. As such, it is essential for DNA replication during cell growth and proliferation (14, 15). In the absence of an exogenous source of dTMP, inhibition of TS results in depletion of intracellular dTMP pools and buildup of dUMP concentrations, leading to cell cycle arrest and programmed cell death (14, 15). Several experimental observations indicate that TS degradation is mediated by the proteasome and that such degradation is ubiquitin-independent (16, 17). First, no ubiquitin-conjugated forms of TS are detectable by biochemical assay such as Western blotting or coimmunoprecipitation (16). Second, genetic abrogation of the ubiquitin conjugation pathway has little or no effect on the intracellular half-life of the TS polypeptide (17). Finally, conversion of the enzyme's 15 Lys residues to Arg, which removes sites of potential ubiquitin conjugation, fails to stabilize the protein (17). Thus, intracellular degradation of TS does not appear to require either ubiquitinylation or the ubiquitinylation pathway.

Proteasomal degradation of TS, similar to ODC, is mediated by a flexible, disordered region. However, in the case of TS, the disordered domain is located at the N- rather than the C-terminal end and is formed by the first 27 amino acids (16, 17). Deletion of just the first few residues can result in a very stable enzyme (16, 17). Furthermore, certain single amino acid substitutions at the penultimate site (Pro-2) can render the polypeptide refractory to proteolysis (17). Thus, the N terminus of TS has a profound impact on its half-life, presumably due to its role in regulating the ability of the enzyme to recognize and/or enter the proteasomal chamber (17).

In the current study we have carried out a more comprehensive analysis of the structure and evolution of the N-terminal domain of TS, focusing on its role in regulating the enzyme intracellular stability. We have identified features of the region that are critical to its function and that provide insights into the mechanism by which ubiquitin-independent proteolysis occurs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and Cell Culture

All cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell line RJK88.13, which is a TS-deficient derivative of V79 Chinese hamster lung cells (18), was obtained from Dr. Robert Nussbaum (University of Pennsylvania) and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Cellgro) containing 4.5 g/liter glucose and supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Cellgro) supplemented with 10 μm thymidine. Cell line Hep2/500, which overexpresses TS (19), was maintained in RPMI medium (Cellgro) containing 4.5 g/liter glucose and supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum.

Plasmid Construction, Mutagenesis, and Transfection

All constructs for mutant analysis were generated using standard molecular biology techniques and were verified directly by DNA sequencing. The parent plasmid for expression of TS and its various mutant derivatives was pJZ205, which contains a full-length TS gene under the control of the SV40 promoter. Mutants were generated by PCR-based methods using a QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Details on all constructs, including primers used for mutagenesis, are available upon request.

Stable and transient transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 or LTX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All plasmids were introduced into the TS-deficient cell line RJK88.13 in media containing 10 μm thymidine. Stable transfectants were selected in thymidine-free medium with or without 5 μm dipyridamole (Sigma), a nucleoside transport inhibitor. The transfectants were pooled and maintained in mass culture.

Protein Extracts and Immunoblotting

TS stability was measured in cycloheximide-treated cells as described previously (16, 17). Cells were split into 60-mm plates, and cycloheximide (50 μg/ml, Sigma) was added after 24 h. Where indicated, cells were preincubated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (25 μm, Sigma) for 4 h before the addition of cycloheximide. Cells were harvested at the indicated times and lysed by sonication (3 × 10 s) in NET2 buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 0.05% Nonidet P-40) containing 10 mm dithiothreitol, 2 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 200 μg/ml aprotinin, 100 μg/ml pepstatin, and 50 μg/ml leupeptin. The crude lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C, and the protein was quantified using the Bio-Rad assay reagent with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Immunoblotting was performed by standard techniques. To detect enhanced green fluorescence protein (eGFP), a monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. sc-9996) was used as probe. Human TS was detected with a monoclonal antibody provided by Dr. Sondra Berger (Department of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Science, University of South Carolina). For detection of Mus musculus TS, a rabbit polyclonal anti-human TS antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. 134130) was utilized. As an internal control for equal loading, blots were re-probed with antibody against actin (Sigma, Clone AC-40). The antigen-antibody complexes were visualized using appropriate secondary antibodies with the ECL chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Biosciences). Densitometry was carried out using ImageJ software maintained by the National Institutes of Health (rsb.info.nih.gov).

Partial Purification of TS

Between 30 and 50 mg of protein in extracts of cell line RJK88.13 or 5 mg of protein in extracts of cell line HEp2/500 were loaded into a 1-ml HiTrap Blue-Sepharose column (Amersham Biosciences) and washed with a buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 1 mm EDTA. Proteins were eluted off the column in three steps using a similar buffer but with 0.2, 0.5, and 1 m KCl. The 0.5 m KCl fraction was desalted and concentrated using Amicon filters and then loaded into a 1-ml HiTrap Q FF column (Amersham Biosciences). Proteins were eluted following the same conditions as those used in the first column. The 0.2 m fraction was further desalted and concentrated using Amicon filters. The resulting preparations were enriched for TS by a factor of ∼5–10-fold.

Analysis of TS by Two-dimensional Gel Electrophoresis

Freshly prepared cell extracts or partially purified preparations of TS (see preceding section) were subjected to two-dimensional gel electrophoresis according to instructions in two- dimensional electrophoresis in the Principles and Methods Handbook (GE Healthcare). Briefly, 11 cm (pH 4.6–7.2) linear ReadyStrip IPG strips (Bio-Rad) were rehydrated overnight in 200 μl of a buffer containing the protein sample, 7 m urea, 2 m thiourea, 2% CHAPS, 2% Pharmalyte, and 0.002% bromphenol blue. Strips were subjected to isoelectric gel electrophoresis under the following conditions: 250 V with rapid climb for 30 min, 8000 V with rapid climb for 150 min, and 8000 V with rapid climb until 30,000 V-h were reached. Typically, 20 μg of sample were focused. After isoelectric gel electrophoresis, the strips were equilibrated for 15 min in a buffer containing 6 m urea, 75 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 29.3% glycerol, 2% SDS, 10 mg/ml dithiothreitol, and 0.002% bromphenol blue followed by a further treatment for 15 min in a similar buffer but containing 25 mg/ml iodoacetamide instead of dithiothreitol. They were transferred directly onto 12.5% pre-cast SDS-PAGE gels and kept in place with 0.5% agarose. SDS-PAGE was performed at 20 °C at 200 V for 1 h. Gels were either stained with Coomassie Blue or transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for immunoblotting. The electrophoretic patterns for TS in cell extracts were identical to those in partially purified preparations of the protein, indicating that no major changes in the enzyme occurred during purification.

MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry (MS)

TS was partially purified and fractionated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis according to the protocols described above. TS forms of interest were excised from the gels, and slices were destained in 50% acetonitrile, 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate, washed with 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate, and shrunken in acetonitrile (ACN). They were subsequently re-swollen in a solution containing 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate and 20 μg/ml trypsin (MS grade; Promega). After 16 h of digestion at 37 °C, peptides were extracted twice using 1% formic acid in 50% (v/v) ACN and concentrated by speed vacuum centrifugation. C18 ZipTips (Millipore) were equilibrated successively with 10 μl of ACN, 10 μl of 50% ACN containing 0.1% v/v formic acid, and 10 μl of 0.1% (v/v) formic acid before binding the peptides. Bound peptides were washed 3 times with 10 μl of 0.1% formic acid and eluted with 2 μl of 50% ACN, 0.1% formic acid. 0.7 μl of eluted peptides were applied on a disposable Prespotted AnchorChip MALDI target plate (Bruker Daltonics) to air-dry. MS analysis was performed using a ReflexIII MALDI-TOF instrument (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) equipped with delayed ion extraction. The mass range was set from 600 to 2500 Da. Precursor ions of interest were selected for fragmentation. All fragment identifications were verified by direct peptide sequencing using MS/MS. Sequence data are available upon request.

Bioinformatics

TS protein sequences for comparative analyses were downloaded from databases maintained by the NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and the EMBL-EBI. Full-length sequences representing 16 mammalian families were examined, including Homo sapiens (human, family Hominidae), Tarsius syrichta (Philippine tarsier, family Tarsiidae), Macaca mulatta (Rhesus monkey, family Cercopithecoidea), Mus musculus (house mouse, family Muridae), Cavia porcellus (domestic guinea pig, family Caviidae), Felis catus (domestic cat, family Felidae), Canis lupus (dog, family Canidae), Bos taurus (cattle, family Bovidae), Equus caballus (horse, family Equidae), Ochotona princeps (American pika, family Ochotonidae), Oryctolagus cuniculus (rabbit, family Leporidae), Tursiops truncatus (bottle-nosed dolphin, family Delphinidae), Loxodonta africana (African savannah elephant, family Elephantidae); Ornithorhynchus anatinus (platypus, order Ornithorhynchidae), Monodelphis domestica (gray short-tailed opossum, family Didelphidae), and Dasypus novemcinctus (nine-banded armadillo, family Dasypodidae). Sequence alignments were carried out using ClustalW2 software, provided by the EMBL-EBI (20). Disorder propensities were calculated using PONDR® VL-XT software (21–23).

RESULTS

The N-terminal Region of TS Functions as a Degron

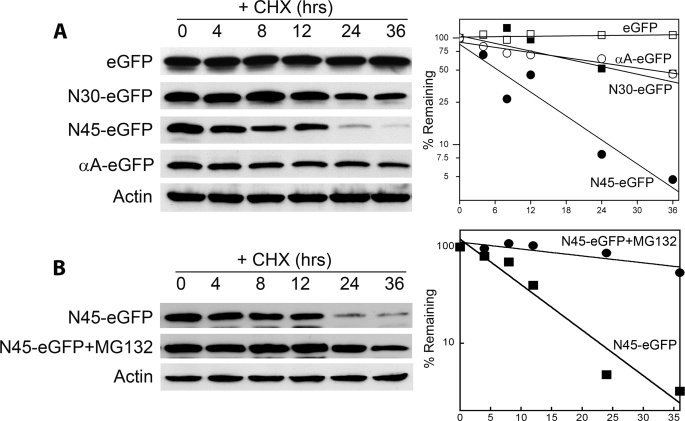

In previous studies we showed that fusion of the N-terminal region of human TS to the body of the Escherichia coli TS polypeptide resulted in a molecule that was significantly destabilized relative to the wild-type E. coli protein (17). This suggested that the N-terminal domain is capable of destabilizing an evolutionarily related polypeptide. To determine whether the region can act as a degron, i.e. if it is capable of destabilizing a completely unrelated protein, we tested its effect on the intracellular degradation of eGFP, a protein that normally has a very long half-life. As seen in Fig. 1A, eGFP is stable for at least 36 h in the presence of cycloheximide. A chimeric polypeptide (denoted N30-eGFP) in which the first 30 residues of TS were fused to the N-terminal end of the eGFP reporter exhibited slight instability compared with eGFP (Fig. 1A), indicating that the disordered region has little if any impact on the stability of the reporter.

FIGURE 1.

The N-terminal domain of TS functions as a degron. A, stably transfected RJK88.13 cells expressing the eGFP reporter itself and the TS-eGFP fusion proteins N30-eGFP, N45-eGFP, or αA-eGFP (see “Results”) were treated for the indicated times with cycloheximide (CHX) and analyzed by Western blotting. The blot was probed with an anti-eGFP antibody and re-probed with an anti-actin antibody as an internal control for loading. The left panel shows the blot, whereas the right panel shows a graphical representation of protein decay as determined by densitometry. B, cells expressing the N45-eGFP fusion protein were treated with cycloheximide either with or without pretreatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 and analyzed as in A.

The first 45 amino acids of TS span the disordered domain (residues 1–27) as well as an α-helix that follows it (helix A; residues 28–45). This region was fused to eGFP, and the resulting chimeric protein (denoted N45-eGFP) was found to have a half-life of ∼7–8 h (Fig. 1A), indicating a large degree of destabilization of the eGFP reporter by the TS-specific sequences.

The observation that N30-eGFP is relatively stable compared with N45-eGFP raised the possibility that helix A alone may be sufficient for degron activity. To test this notion, we examined a fusion protein containing only helix A (i.e. residues 30–45) ligated to the eGFP reporter. This protein, termed αA-eGFP, was quite stable relative to the unfused reporter (Fig. 1A), indicating that helix A does not on its own have strong degron activity.

Treatment of cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 significantly increased the half-life of the N45-eGFP polypeptide (Fig. 1B). Thus, degradation of the chimeric protein is proteasome-mediated.

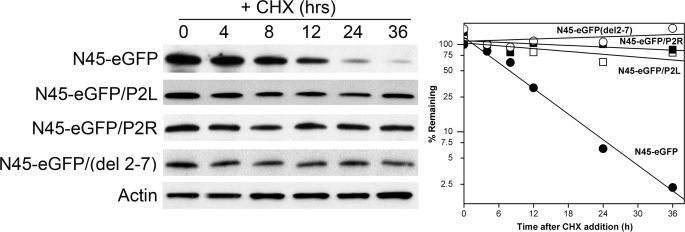

To assure that degradation promoted by the TS-specific region of N45-eGFP occurs by the same mechanism as in normal, wild-type TS, we examined several mutants that are known to affect the stability of the latter. Substitution mutants P2L and P2R, both of which stabilize wild-type TS (see below and Ref. 17), were introduced into N45-eGFP; each substitution resulted in stabilization of the chimeric molecule (Fig. 2). Similarly, deletion of residues 2–7, which stabilizes wild-type TS (16, 17), also renders the fusion polypeptide resistant to degradation (Fig. 2). Thus, the degradation phenotypes of both wild-type TS and the chimeric N45-eGFP protein are similarly affected by amino acid substitutions, indicating that the N-terminal domain functions through a shared biochemical mechanism in both proteins.

FIGURE 2.

Amino acid substitutions that stabilize normal TS also stabilize the TS-eGFP fusion protein. RJK88.13 cells expressing fusion proteins N45-eGFP, N45-eGFP/P2L, N45-eGFP/P2R, and N45-eGFP/del(2–7) (see “Results”) were treated for the indicated times with cycloheximide (CHX) and analyzed by Western blotting. The blot was probed with an anti-eGFP antibody and re-probed with an anti-actin antibody as an internal control for loading. The left panel shows the blot, whereas the right panel shows a graphical representation of protein decay as determined by densitometry.

We conclude from these experiments that the N-terminal region of human TS functions as a degron in promoting degradation of an unrelated polypeptide to which it is ligated. Neither the disordered domain (residues 2–30) nor helix A (residues 30–45) is very active on its own, indicating that both regions are required for maximal degron activity.

Conserved Features of the N-terminal Domain during Mammalian Evolution

The N terminus of TS is extended in the mammalian as compared with the prokaryotic enzyme (14, 24, 25). This region in human TS is relatively Pro-rich, with 8 of the first 27 residues (29.5%) being Pro as compared with 15 of the remaining 286 (5.2%). X-ray crystallography of the human and rat enzymes has shown that the region is intrinsically disordered (24–27). To gain insight into the extent of conservation of these and other features of the TS polypeptide, we carried out a comparative analysis of TS sequences from 16 mammalian species. The sequences, which were obtained from databases maintained by the NCBI and the EMBL-EBI, represent 16 distinct taxonomic families (in the discussion below, all residue numbers refer to human TS).

Certain amino acids (i.e. Met, Arg, Gln, Ser, Pro, Glu, Lys, and Asp) have been identified as disorder-promoting in that they are found at elevated frequencies in disordered regions of proteins (22, 28, 29). Other amino acids (i.e. Trp, Cys, Phe, Ile, Val, Tyr, Leu, Asn, and His) are order-promoting, occurring at reduced frequencies in disordered regions (22, 28, 29). We determined the compositions of both disorder- and order-promoting amino acids in TS polypeptides from all 16 mammalian species as a group. In the disordered region (corresponding to residues 2–27 of human TS), average frequencies for disorder-promoting residues were 0.085 ± 0.095, whereas those for order-promoting residues were 0.0094 ± 0.0059, indicating a 9-fold higher frequency for the former (p = 0.033). In contrast, for the rest of the polypeptide (corresponding to residues 28–313), frequencies for disorder- and order-promoting residues were nearly identical (i.e. 0.052 ± 0.013 and 0.045 ± 0.0092, respectively). Thus, as is characteristic of intrinsically flexible domains, the N-terminal region is enriched for disorder-promoting amino acids and deficient in order-promoting residues.

For each species we assessed the propensity for disorder within the N-terminal region (i.e. that corresponding to residues 2–27) using the neural predictor PONDR® VL-XT (21–23). VL-XT provides values between 0 (complete order) and 1 (complete disorder), with significant disorder indicated by values ≥0.5. Table 1 shows that all species have high propensities for disorder, with PONDR® scores averaging 0.872 ± 0.0657. Thus, a high level of flexibility appears to be a common feature of the N terminus of TS, a characteristic that is conserved among mammalian species.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the N-terminal domain of TS in mammalian species

Full-length protein sequences were downloaded from public databases maintained by the EBI-EMBL and the NCBI. Disorder propensities are represented by PONDR® scores (range 0.0–1.0, with 1.0 being the highest). Proline contents are for the N terminus (corresponding to residues 2–27 of human TS) and the remainder of the protein (residues 28–313).

| Species | Disorder propensity | Proline content |

Penultimate residue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N terminus (fraction) | Remainder (fraction) | |||

| H. sapiens | 0.824 | 8/26 (0.31) | 15/286 (0.052) | Pro |

| T. syrichta | 0.886 | 8/26 (0.31) | 14/286 (0.049) | Pro |

| M. mulatta | 0.824 | 8/26 (0.31) | 15/286 (0.052) | Pro |

| M. musculus | 0.691 | 1/20 (0.050) | 15/286 (0.052) | Leu |

| C. porcellus | 0.856 | 7/27 (0.26) | 15/283 (0.053) | Pro |

| F. catus | 0.929 | 10/29 (0.34) | 15/286 (0.052) | Pro |

| C. lupus | 0.921 | 11/27 (0.41) | 15/286 (0.052) | Pro |

| B. taurus | 0.944 | 12/29 (0.41) | 16/324 (0.049) | Pro |

| E. caballus | 0.817 | 7/25 (0.28) | 15/286 (0.050) | Pro |

| O. princeps | 0.920 | 7/26 (0.27) | 15/286 (0.052) | Pro |

| O. cunicula | 0.897 | 6/23 (0.26) | 15/286 (0.052) | Pro |

| T. truncatus | 0.920 | 9/28 (0.32) | 15/286 (0.052) | Pro |

| L. africana | 0.919 | 9/22 (0.41) | 14/286 (0.050) | Pro |

| O. anatinus | 0.924 | 10/26 (0.38) | 15/286 (0.052) | Pro |

| M. domestica | 0.949 | 12/48 (0.25) | 15/286 (0.052) | Pro |

| D. novemcinctus | 0.871 | 6/27 (0.22) | 14/265 (0.052) | Pro |

| Average | 0.87 ± 0.07 | 0.32 ± 0.058a | 0.051 ± 0.0012 | |

a Not including M. musculus.

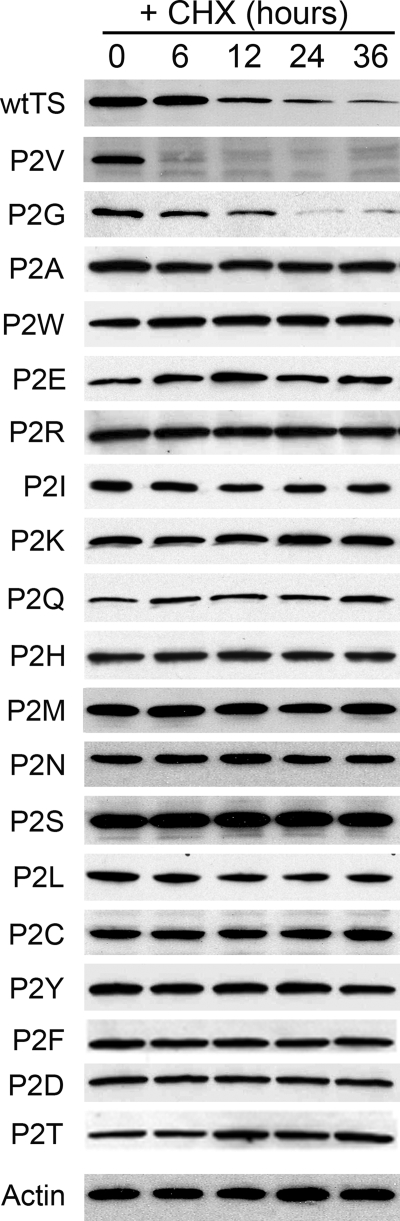

To carry out further comparisons of mammalian TS polypeptides, the sequences were aligned using the ClustalW2 program. The N-terminal domain (corresponding to residues 1–37 of human TS) is shown in Fig. 3, whereas the rest of the molecule (corresponding to residues 28–313) is presented in supplemental Fig. S1. Inspection of the alignments immediately revealed that amino acid substitutions are far more abundant in the N-terminal region as compared with the rest of the polypeptide. Only 7.7% of sites within the N-terminal domain (i.e. 2/26, not including the initiator Met) are identical (Fig. 3) compared with 46.2% (132/286) in the remainder of the molecule (supplemental Fig. S1). The only fully conserved residues in the N-terminal domain form a Gly-Ser motif at amino acids 5 and 6. Conservative or semi-conservative substitutions do not occur in the alignment of the N-terminal domain but occur at 39.5% of sites (113/286) in the rest of the polypeptide. Clearly, the intrinsically disordered N-terminal region of TS is hypervariable among mammalian species compared with the rest of the protein. That disordered domains evolve more rapidly than ordered regions has been noted previously and appears to represent a general lack of constraint within the former (30).

FIGURE 3.

Alignment of amino acid sequences within the disordered N-terminal domains of mammalian TS polypeptides. TS protein sequences from mammalian species representing 16 individual taxonomic families (see “Experimental Procedures” for list of species) were downloaded from public databases maintained by the NCBI and the EMBL-EBI and aligned using ClustalW2 software. The region corresponding to residues 1–37 of human TS is shown. The disordered region is boxed, and residue numbers are indicated on the right. Prolines are underlined to highlight their high incidence. Symbols at the bottom of the alignment indicate the degree of conservation for each residue, with the asterisks (*) indicating complete identity and the colon (:) indicating conserved substitutions.

Further inspection of the alignment indicated that with the exception of M. musculus, the N-terminal domain of each species has a high Pro content (Fig. 3, Table 1). The fraction of Pro is, on average, 0.32 ± 0.058 for the N-terminal domain (not including M. musculus) but only 0.051 ± 0.0012 for the rest of the molecule (p < 0.0001). The Pro residues cluster into two regions; one at positions 9–15 and a second at 24–27 (Fig. 3).

In nearly all species Pro occurs at the penultimate position; again, the only exception is M. musculus, which has Leu at this site (Fig. 3; Table 1). The prevalence of Pro at position 2 may be important in light of the data presented below, which indicate an important role for the penultimate residue in determining TS degradation.

In sum, although extensive sequence divergence has accumulated during evolution of the N-terminal domain of mammalian TS, a disordered structure, a high Pro content, and a Pro residue at the penultimate site have been conserved. The M. musculus enzyme does not follow this pattern in that its N-terminal region, which is the shortest among the species examined, has a relatively low Pro content and Leu in place of Pro at the penultimate site.

Impact of the Penultimate Residue on TS Degradation

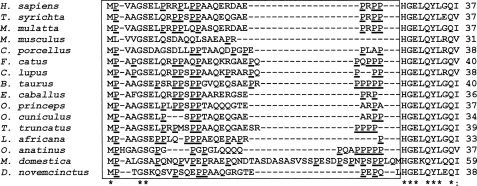

Our previous work showed that several amino acid substitutions at Pro-2 profoundly stabilize the TS polypeptide (17). Specifically, the P2A, P2W, P2R, P2D, and P2Y enzymes were found to be quite stable relative to wild-type TS, whereas the P2V and P2G mutants were unstable, having half-lives similar to or less than wild type TS. To extend these findings, we generated the remaining 12 substitution mutants and measured their degradation rates. Fig. 4 shows results for the wild-type enzyme and all 19 substitution mutants. Mutants P2V and P2G were relatively unstable, having half-lives of 1–2 and 6–8 h, respectively; all the other molecules exhibited half-lives of >36–48 h, indicating that they are quite stable. Thus, degradation of TS requires Pro, Val, or Gly at residue 2, a feature that may represent a selective constraint underlying the high conservation of Pro at this site in mammals (see above).

FIGURE 4.

The penultimate residue (Pro-2) regulates degradation of the TS polypeptide. Stably transfected RJK88.13 cells expressing either wild-type TS (wtTS) or mutant forms with specified substitutions at residue 2 (identified to the left) were treated for the indicated times with cycloheximide (CHX) and analyzed by Western blotting. The blot was probed with an anti-TS antibody and re-probed with an actin antibody as an internal control for loading.

Post-translational Processing of the N-terminal End of TS

Having observed that amino acid substitutions at Pro-2 can a have profound impact on the intracellular stability of TS, we considered the potential role of post-translational N-terminal processing as a determinant of the enzyme half-life. Two primary modifications are known to occur at the N termini of proteins. Cleavage of the initiator Met, which results in the penultimate amino acid becoming the N-terminal residue in the mature polypeptide, is commonly observed (31–33). Several studies have shown that polypeptides with small side chains at the penultimate position (i.e. Ala, Pro, Gly, Cys, Ser, Thr, and Val) readily undergo Met cleavage, whereas those with large radii (i.e. the remaining 12) are relatively resistant to cleavage (31, 34). Another common mode of protein modification is Nα-acetylation, which has been estimated to occur in 30% or more of the proteins within eukaryotic cells (33, 35, 36). Although the sequence determinants for Nα-acetylation are not well defined, evidence does indicate that the penultimate residue is important (33, 35, 36).

As an initial test of whether or not changes in N-terminal processing (particularly Nα-acetylation) are associated with alterations in enzyme stability among mutant TS molecules, we compared the pI values of TS polypeptides by two-dimensional acrylamide gel electrophoresis. This approach was based on the supposition that Nα-acetylation, in converting a free N-terminal amino group to an acetylated group, is expected to lower the pI of a protein and would be detected as a mobility shift on two-dimensional gels. As shown in supplemental Fig. S2, similar mobilities were observed for the wild-type, P2V, and P2G enzymes, all of which are unstable, with half-lives of ≤6 h (see Fig. 4); in contrast, the degradation-resistant P2A, P2L, P2D, P2S, and P2R enzymes were more acidic than expected. These observations are consistent with the notion that unstable TS molecules have free, unacetylated N-terminal ends, whereas the stable molecules have modified, i.e. Nα-acetylated, ends.

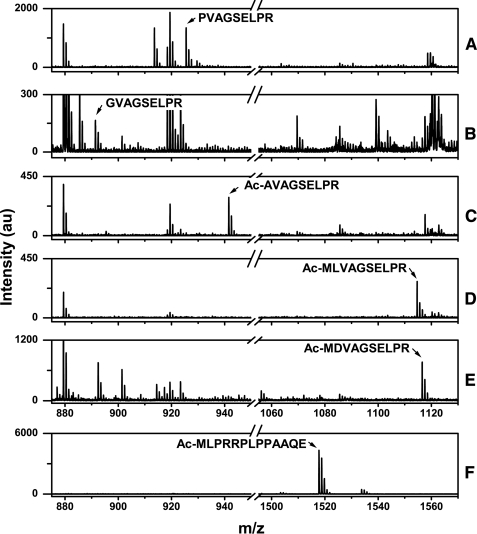

To verify this notion, we examined the structure of the N terminus by MALDI-TOF MS. Edman degradation experiments carried out many years ago showed that the primary sequence of human TS begins with an unblocked Pro residue, indicating that the protein undergoes Met excision but not Nα-acetylation (37). We have confirmed this observation by examining the tryptic fingerprint of TS derived from human cell line HEp-2/500. Analysis of the most abundant charge form ( supplemental Fig. S2) revealed a fragment at m/z 925.32, which is the size expected for the peptide PVAGSELPR at residues 2–10 (Fig. 5A). Importantly, no fragments with m/z ratios corresponding to residues 1–10 or to N-α-acetylated derivatives of residues 1–10 or 2–10 were detected. Isolation and direct sequencing of the m/z 925.32 fragment by MS/MS verified that it indeed corresponds to residues 2–10. Thus, wild-type human TS undergoes Met excision but not Nα-acetylation, resulting in a free, non-acetylated Pro residue at the N terminus.

FIGURE 5.

MALDI-TOF MS analysis of Nα-acetylation. Partially purified preparations of wild-type TS as well as various mutant forms were extracted from two-dimensional acrylamide gels, digested with either trypsin (panels A–E) or endoproteinase Glu-C (panel F), and analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. For each enzyme the most abundant charge form (see supplemental Fig. S2) was analyzed. Fingerprints were determined for the following TS molecules: A, wild-type TS; B, P2G; C, P2A; D, P2L; E, P2D; F, del(2–7). The N-terminal peptide and its sequence are indicated in each panel. au, arbitrary units.

Next, we analyzed representative mutant TS polypeptides, including those with unstable (like wild-type TS) and stable phenotypes. In each case we focused on the most abundant charge form (supplemental Fig. 2). The P2G enzyme, which is degraded with a half-life similar to the wild-type protein (see Fig. 4), revealed a tryptic fragment at m/z 885.48 corresponding to peptide GVAGSELPR at residues 2–10 (Fig. 5B). No fragments with m/z ratios corresponding to other derivatives of this peptide were observed. Thus, the P2G mutant, like the wild-type protein, undergoes Met excision but not Nα-acetylation.

Several metabolically stable TS molecules were examined. The P2A enzyme yielded a tryptic fragment at m/z 941.52 which corresponds to an Nα-acetylated derivative of peptide AVAGSELPR at residues 2–10 (Fig. 5C); thus, the polypeptide is subject to both Met excision and Nα-acetylation. For the P2L and P2D mutants, tryptic fragments at m/z 1114.64 and 1116.53, corresponding to the Nα-acetylated forms of peptides MLVAGSELPR and MDVAGSELPR, respectively, at residues 1–10, were identified (Fig. 5, D and E). Thus, these two enzymes do not undergo Met excision but are susceptible to Nα-acetylation.

Finally, digestion of another stable TS enzyme, deletion mutant del(2–7), with endoproteinase Glu-C resulted in a fragment at m/z 1517.80 (Fig. 5F), corresponding to the Nα-acetylated form of peptide MLPRRPLPPAAQE at positions 1–13; thus, Met is retained in this mutant and is Nα-acetylated.

In sum, the results of both two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and MALDI-TOF MS indicate that unstable TS polypeptides have predominantly free, non-acetylated N termini, whereas stable polypeptides have termini modified by Nα-acetylation. Thus, the presence of an acetylated N terminus is associated with a stable phenotype, indicating that degradation is inhibited by blocking the N-terminal amino group. The presence or absence of the initiator Met in the various mutants follows established “rules” regarding the impact of the penultimate residue on the excision process (31, 34). However, Met cleavage does not itself appear to be a determinant of stability.

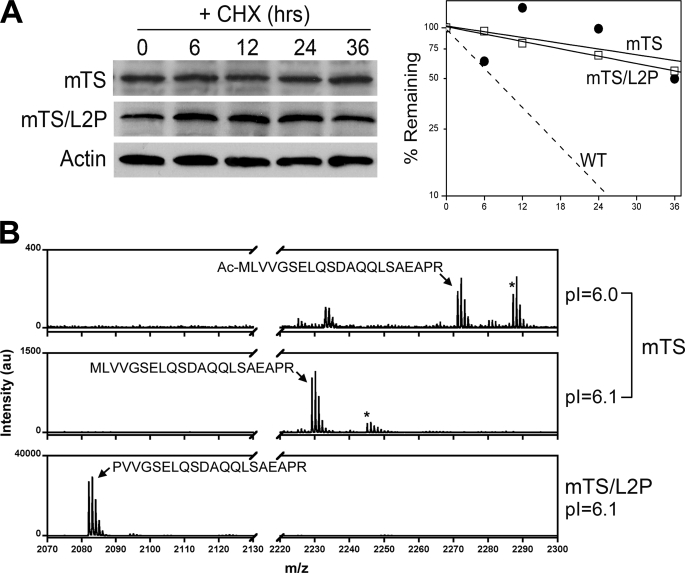

Protection against Nα-Acetylation Is Not Sufficient for Degradation

The TS polypeptide from M. musculus, which contains Leu at the penultimate site (see Fig. 3), has been shown to have an acetylated N terminus (38). This leads to the prediction that the enzyme should be relatively resistant to degradation. Furthermore, it predicts that converting Leu-2 to Pro should destabilize the polypeptide, as such a substitution should lead to excision of the initiator Met and a free, non-acetylated Pro at the N terminus. As seen in Fig. 6A, TS from M. musculus (denoted mTS) is, as predicted, quite stable. However, the L2P mutant (mTS/L2P) is just as stable. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (supplemental Fig. S3) and MALDI-TOF MS (Fig. 6B) showed that the mTS and mTS/L2P polypeptides differ as expected at their N-terminal ends. The equally stable phenotype of both enzymes indicates that the occurrence of a free, non-acetylated N-terminal end is not on its own sufficient for degradation; rather, one or more other features of TS structure are required.

FIGURE 6.

Degradation of TS from M. musculus. A, RJK88.13 cells expressing either wild-type M. musculus TS (mTS) or a mutant in which Leu-2 was converted to Pro (mTS/L2P) were treated for the indicated times with cycloheximide (CHX) and analyzed by Western blotting. The blot was probed with antibody that recognizes mouse TS; blots were re-probed with an anti-actin antibody as an internal control for loading. The left panel shows the blot, whereas the right panel shows graphical representations of protein decay as determined by densitometry. The dashed line is a representative decay plot for wild-type human TS (WT). B, partially purified preparations of the mTS and mTA/L2P enzymes were fractionated by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and TS was extracted from the gels, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. The upper and middle panels show fingerprints for the acidic and basic forms, respectively, of mTS (see supplemental Fig. S3); the lower panel shows the fingerprint for the single form of mTS/L2P (see supplemental Fig. S3). The N-terminal peptide and its sequence are indicated in each panel. Asterisks (*) indicate isoforms that contain oxidized methionine. au, arbitrary units.

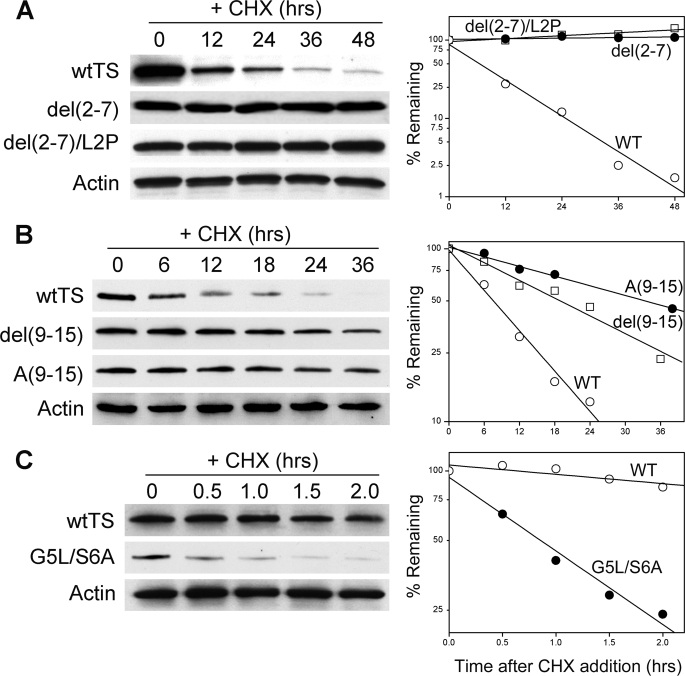

To pursue this notion, we examined additional mutants within the N-terminal domain. We replaced Leu with Pro at position 2 of the highly stable del(2–7) mutant. Similar to the mTS/L2P polypeptide, this substitution was expected to result in a non-acetylated N-terminal Pro and an unstable phenotype. As seen in Fig. 7A, the mutant, denoted del(2–7)/L2P, is as stable as the parental del(2–7) molecule. Thus, one or more amino acids in the region between residues 2 and 7 promote degradation. Apparently, a non-acetylated N-terminal end is not sufficient for degradation.

FIGURE 7.

Modulation of TS degradation independently of Nα-acetylation. Stably transfected RJK88.13 cells expressing various TS molecules were treated for the indicated times with cycloheximide and analyzed by Western blotting. The analysis included cells expressing the following: A, wild-type human TS (WT), the del(2–7) mutant, and the del(2–7)/L2P mutant; B, wild-type human TS (WT), the del(9–15) mutant, and the A(9–15) mutant; and C, wild-type human TS (WT) and the G5L/S6A mutant. Blots were probed with antibody to human TS and were re-probed with an anti-actin antibody as an internal control for loading. The left panels show the blots, whereas the right panels show graphical representations of protein decay, as determined by densitometry.

As a further corroboration of this conclusion, we analyzed a mutant in which residues 9–15, a Pro-rich segment that is highly divergent among mammalian TS molecules (see alignment of Fig. 3), were deleted. The MS fingerprint of this mutant, denoted del(9–15), indicates that it has a free, non-acetylated Pro at its N terminus as expected (data not shown). However, despite its non-acetylated character, it is quite stable relative to the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 7B). Thus, although the mutant was not subject to Nα-acetylation, it was relatively resistant to degradation, indicating that one or more amino acids spanning the region between residues 9 and 15 promotes TS degradation.

It is possible that the relatively stable phenotype of the del(9–15) mutant is due to a shortening of the N-terminal domain rather than changes in the specific sequence. We, therefore, constructed a mutant in which residues 9–15 were converted to Ala, thus maintaining length but changing the sequence. As seen in Fig. 7B, this mutant, termed A(9–15), was markedly more stable than the wild-type enzyme. The results indicate that one or more amino acids between residues 9 and 15 is a critical determinant of enzyme stability.

Finally, having noted that the Gly-Ser motif at residues 5 and 6 is conserved (see Fig. 3), we investigated its function by substituting Leu and Ala, respectively, at these two sites. The mutant, denoted G5L/S6A, was found to have a relatively short half-life of ∼1–2 h (Fig. 7C); it is stabilized by MG132 (data not shown), indicating that its degradation is carried out by the proteasome. Thus, the Gly-Ser dipeptide inhibits the degron activity of the N-terminal domain and functions as a stabilizing motif in control of TS degradation.

The results described above favor the notion that a free, non-acetylated N terminus is necessary but not sufficient for TS degradation. Various regions within the N-terminal domain modulate the enzyme susceptibility to intracellular degradation via mechanisms that are independent of Nα-acetylation.

DISCUSSION

Although a number of substrates for the ubiquitin-independent degradation pathway have been identified (4–8, 10, 11, 39), little is known about the mechanisms involved. Earlier studies from our laboratory showed that degradation of TS, which is a substrate of the ubiquitin-independent pathway, is mediated by a structurally flexible domain at the enzyme N-terminal end (16, 17). Experiments presented in the present report indicate that this region, in cooperation with the helix that follows it, acts as a degron, i.e. it has the ability to destabilize an unrelated protein (eGFP) to which it is fused. The TS degron functions by similar mechanisms in wild-type TS and when fused to the eGFP reporter, as indicated by the observation that the P2L, P2R, and del(2–7) substitutions within the degron led to profound stabilization of both proteins (see Fig. 2).

It is becoming apparent that intrinsically disordered protein regions, such as that in TS, are important in mediating protein degradation by the proteasome. Elegant studies by Matouschek and co-workers (40) demonstrated that for ubiquitinylated proteins, disordered protein termini represent sites of initial entry of the target polypeptide into the proteasome proteolytic chamber. A similar suggestion has been made for ODC, in which a flexible 37-residue region located at the C-terminal end of the polypeptide regulates docking to the proteasome and entry into the proteasomal chamber (4, 6). It is feasible that the N-terminal domain of TS plays such a role. Alternatively, the TS domain may bind to some sort of accessory protein that tethers the target substrate to the proteasome, as occurs in regulation of c-Jun degradation by the HTLV basic leucine zipper factor protein of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (12).

Evolutionary analysis of the TS primary sequence showed that during mammalian speciation, the N-terminal domain has diverged extensively relative to the rest of the molecule. Despite this high degree of divergence, several features of the domain, including its disordered nature, its high Pro content, and the occurrence of Pro at the penultimate site, have been preserved (see Fig. 3, Table 1, and supplemental Fig. S1). These features are likely to place only weak constraints on the sequence, thereby allowing considerable tolerance to amino acid substitutions.

The Pro residues occur in two clusters within the disordered domain. The first occurs at amino acids 9–15, which spans a region that is important to degron activity (Fig. 7). It is possible that these residues form a substructure that is critical to interaction with the proteasome directly or with an accessory protein involved in recognizing the proteasome. Disordered regions typically may contain short, extended helical structures termed polyprotein II helices that are often Pro-rich (29, 41). The second Pro cluster is found at residues 24–27 near the end of the disordered domain and may form a flexible hinge that contributes to the overall movement of the domain. It is unlikely that the flexibility of this region, should it exist, plays a role in degradation, as deletion of amino acids 24–27 has no detectable impact on the half-life of the TS polypeptide.4

Interestingly, the TS molecule from mouse (M. musculus) does not conform to these patterns. The N-terminal region of this species does retain a relatively high disorder propensity, although it is slightly lower than that for the other species (Table 1). However, the Pro content of the region is not elevated, and Leu rather than Pro occupies the penultimate site (Table 1). The presence of Leu at position 2 causes the polypeptide to have an Nα-acetylated Met at its N terminus, rendering it resistant to proteasomal degradation (Fig. 6A).

Using MALDI-TOF MS, we verified earlier studies demonstrating that wild-type TS undergoes post-translational excision of the initiator Met residue, leaving a free, unblocked Pro at its N terminus (37). Of interest in the current report is the observation of a tight correlation between intracellular stability and Nα-acetylation in several mutant TS polypeptides. Gly in place of Pro at residue 2 results in an enzyme with a non-acetylated N terminus and a half-life of ∼6 h, similar to the wild-type protein; in contrast, Ala, Asp, and Leu substitutions at this site as well as deletion of the first six residues results in acetylated N termini and half-lives of ≥24–36 h. These findings suggest that Nα-acetylation inhibits proteasomal degradation of TS and that the N-terminal end of the polypeptide must retain a free, unmodified amino group to be recognized as a proteasomal substrate. The presence or absence of the initiator Met appears to be unimportant to TS degradation. Among the stable mutants with substitutions at position 2, some (e.g. P2D and P2L) retain the initiator Met, whereas others (e.g. P2A) lose it. Importantly, all are subject to Nα-acetylation, indicating the latter process to be critical.

N-terminal Pro is not a substrate for the acetyltransferases that catalyze Nα-acetylation and is not found among proteins with acetylated N termini (36, 42). Thus, exposure of a Pro residue after Met excision results in a free, unmodified N-terminal end that is protected from acetylation. It may be that evolutionary conservation of Pro at the penultimate site of TS reflects the need to preserve a free N-terminal end.

Although post-translational Nα-acetylation occurs on 30% or more of proteins within eukaryotic cells (33, 35, 36), its function is poorly understood. However, a role for the process in degradation has been suggested. Proteomic and biochemical studies have indicated that Nα-acetylation inhibits degradation by the proteasome in general (43–46). Among the few specific proteins whose half-lives are modulated by Nα-acetylation are hypoxanthine ribosyltransferase (47) and p21Cip1 (39). Although the mechanisms underlying such effects are not known, one hypothesis is that acetylation of the N-terminal amino group inhibits ubiquitinylation at that site, which in turn leads to reduced interaction with the 26 S proteasome and stabilization (39). For TS, ubiquitinylation of the protein does not occur and plays no apparent role in the protein half-life (16, 17); it is, therefore, unlikely that the enzyme is subject to N-terminal ubiquitinylation. It may be that a free N terminus on TS is required for the entry into the proteasomal chamber, similar to what has been postulated for ODC (4–6). This is reminiscent of N-end rule substrates of the ClpAP protease, a prokaryotic complex that recognizes and degrades target protein substrates with free, unblocked N termini (48).

Although freedom from Nα-acetylation is critical to normal degradation of the TS polypeptide, other residues within the N-terminal domain are involved. Indeed, several regions appear to have an impact on degradation, even in the presence of a free, non-acetylated N terminus. Deletion of residues 2–7 or 9–15 stabilizes the protein, whereas substitutions at the evolutionarily conserved Gly-5—Ser-6 motif destabilize it (Fig. 7). It is apparent, therefore, that a free, unmodified N-terminal end, although necessary, is not sufficient for degradation. Again, this is consistent with what has been found for ClpAP-directed proteolysis in prokaryotes (48).

An appropriate in vitro biochemical system will be necessary for further dissection of the mechanism of TS degradation. Unfortunately, we have been unable to faithfully mimic the intracellular half-life of TS in vitro using either rabbit reticulocyte extracts or purified proteasomes.4 This may reflect the need of one or more accessory factors that are absent from these biochemical systems. Further efforts to develop an appropriate in vitro system for biochemical analysis of TS degradation are under way.

Because TS is the sole de novo source of dTMP for cell growth, it is an important target for cytotoxic agents used in control of cancer (14, 15). The enzyme degradation rate has important implications with regard to the efficacy of such agents. First, the rather long half-life of TS keeps the enzyme intracellular concentration elevated even when synthetic rates are low. Thus, TS-targeted drugs must be delivered at high doses and sustained over long periods of time to reach the sought-after goals of reducing thymidylate pools and promoting cell death. Also, the high stability of TS potentially constrains attempts to down-regulate enzyme synthesis via siRNA or other antisense strategies (49, 50), as such down-regulation will occur slowly due to the enzyme long half-life. In all, improving the effectiveness of TS-targeted therapies will likely require destabilization of the protein.

In sum, the results reported herein place TS as a potentially useful model for studies aimed at understanding ubiquitin-independent protein degradation by the proteasome, a process that is increasingly being recognized as having broad occurrence in eukaryotic cells. Further understanding of the mechanism by which the TS molecule is degraded within the cell will also be useful in efforts to enhance the effectiveness of TS-directed, chemotherapeutic strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Sangita Koli for technical help.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant CA44013.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

S. Melo, unpublished data.

- ODC

- ornithine decarboxylase

- TS

- thymidylate synthase

- CHAPS

- 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid

- MALDI-TOF

- matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight

- ACN

- acetonitrile

- eGFP

- enhanced green fluorescence protein

- mTS

- M. musculus from TS

- MS

- mass spectrometry.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ciechanover A. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 7151–7160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glickman M. H., Ciechanover A. (2002) Physiol. Rev. 82, 373–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jariel-Encontre I., Bossis G., Piechaczyk M. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1786, 153–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeuchi J., Chen H., Coffino P. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 123–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang M., MacDonald A. I., Hoyt M. A., Coffino P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 20959–20965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang M., Pickart C. M., Coffino P. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 1488–1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bossis G., Ferrara P., Acquaviva C., Jariel-Encontre I., Piechaczyk M. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 7425–7436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basbous J., Jariel-Encontre I., Gomard T., Bossis G., Piechaczyk M. (2008) Biochimie 90, 296–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin Y., Lee H., Zeng S. X., Dai M. S., Lu H. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 6365–6377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X., Amazit L., Long W., Lonard D. M., Monaco J. J., O'Malley B. W. (2007) Mol. Cell 26, 831–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuksek K., Chen W. L., Chien D., Ou J. H. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 612–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isono O., Ohshima T., Saeki Y., Matsumoto J., Hijikata M., Tanaka K., Shimotohno K. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 34273–34282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baugh J. M., Viktorova E. G., Pilipenko E. V. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 386, 814–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carreras C. W., Santi D. V. (1995) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64, 721–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger F. G., Berger S. H. (2006) Cancer Biol. Ther. 5, 1238–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forsthoefel A. M., Peña M. M., Xing Y. Y., Rafique Z., Berger F. G. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 1972–1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peña M. M., Xing Y. Y., Koli S., Berger F. G. (2006) Biochem. J. 394, 355–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nussbaum R. L., Walmsley R. M., Lesko J. G., Airhart S. D., Ledbetter D. H. (1985) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 37, 1192–1205 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger S. H., Jenh C. H., Johnson L. F., Berger F. G. (1985) Mol. Pharmacol. 28, 461–467 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I. M., Wilm A., Lopez R., Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G. (2007) Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X., Romero P., Rani M., Dunker A. K., Obradovic Z. (1999) Genome Inform. Ser. Workshop Genome Inform. 10, 30–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romero P., Obradovic Z., Li X., Garner E. C., Brown C. J., Dunker A. K. (2001) Proteins 42, 38–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferron F., Longhi S., Canard B., Karlin D. (2006) Proteins 65, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardy L. W., Finer-Moore J. S., Montfort W. R., Jones M. O., Santi D. V., Stroud R. M. (1987) Science 235, 448–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schiffer C. A., Clifton I. J., Davisson V. J., Santi D. V., Stroud R. M. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 16279–16287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phan J., Koli S., Minor W., Dunlap R. B., Berger S. H., Lebioda L. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 1897–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phan J., Steadman D. J., Koli S., Ding W. C., Minor W., Dunlap R. B., Berger S. H., Lebioda L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 14170–14177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunker A. K., Oldfield C. J., Meng J., Romero P., Yang J. Y., Chen J. W., Vacic V., Obradovic Z., Uversky V. N. (2008) BMC Genomics 9, Suppl 2, S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunker A. K., Silman I., Uversky V. N., Sussman J. L. (2008) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18, 756–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown C. J., Takayama S., Campen A. M., Vise P., Marshall T. W., Oldfield C. J., Williams C. J., Dunker A. K. (2002) J. Mol. Evol. 55, 104–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frottin F., Martinez A., Peynot P., Mitra S., Holz R. C., Giglione C., Meinnel T. (2006) Mol. Cell Proteomics 5, 2336–2349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giglione C., Boularot A., Meinnel T. (2004) Cell Mol Life Sci. 61, 1455–1474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez A., Traverso J. A., Valot B., Ferro M., Espagne C., Ephritikhine G., Zivy M., Giglione C., Meinnel T. (2008) Proteomics 8, 2809–2831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirel P. H., Schmitter M. J., Dessen P., Fayat G., Blanquet S. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 8247–8251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polevoda B., Sherman F. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 36479–36482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polevoda B., Sherman F. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 325, 595–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimizu K., Ayusawa D., Takeishi K., Seno T. (1985) J. Biochem. 97, 845–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cieœla J., Fraczyk T., Zieliñski Z., Sikora J., Rode W. (2006) Acta Biochim. Pol. 53, 189–198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen X., Chi Y., Bloecher A., Aebersold R., Clurman B. E., Roberts J. M. (2004) Mol. Cell 16, 839–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prakash S., Tian L., Ratliff K. S., Lehotzky R. E., Matouschek A. (2004) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 830–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stapley B. J., Creamer T. P. (1999) Protein Sci. 8, 587–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arnesen T., Van Damme P., Polevoda B., Helsens K., Evjenth R., Colaert N., Varhaug J. E., Vandekerckhove J., Lillehaug J. R., Sherman F., Gevaert K. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8157–8162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hershko A., Heller H., Eytan E., Kaklij G., Rose I. A. (1984) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 81, 7021–7025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mayer A., Siegel N. R., Schwartz A. L., Ciechanover A. (1989) Science 244, 1480–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meinnel T., Peynot P., Giglione C. (2005) Biochimie 87, 701–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meinnel T., Serero A., Giglione C. (2006) Biol. Chem. 387, 839–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson G. G., Kronert W. A., Bernstein S. I., Chapman V. M., Smith K. D. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 9079–9082 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang K. H., Oakes E. S., Sauer R. T., Baker T. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 24600–24607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Z., Cloud A., Hughes D., Johnson L. F. (2006) Cancer Gene Ther. 13, 107–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin S. B., Ts'o P. O., Sun S. K., Choo K. B., Yang F. Y., Lim Y. P., Tsai H. L., Au L. C. (2001) Mol. Pharmacol. 60, 474–479 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.