Abstract

Mahogunin ring finger-1 (MGRN1) is a RING domain-containing ubiquitin ligase mutated in mahoganoid, a mouse mutation causing coat color darkening, congenital heart defects, high embryonic lethality, and spongiform neurodegeneration. The melanocortin hormones regulate pigmentation, cortisol production, food intake, and body weight by signaling through five G protein-coupled receptors positively coupled to the cAMP pathway (MC1R–MC5R). Genetic analysis has shown that mouse Mgrn1 is an accessory protein for melanocortin signaling that may inhibit MC1R and MC4R by unknown mechanisms. These melanocortin receptors (MCRs) regulate pigmentation and body weight, respectively. We show that human melanoma cells express 4 MGRN1 isoforms differing in the C-terminal exon 17 and in usage of exon 12. This exon contains nuclear localization signals. MGRN1 isoforms decreased MC1R and MC4R signaling to cAMP, without effect on β2-adrenergic receptor. Inhibition was independent on receptor plasma membrane expression, ubiquitylation, internalization, or stability and occurred upstream of Gαs binding to/activation of adenylyl cyclase. MGRN1 co-immunoprecipitated with MCRs, suggesting a physical interaction of the proteins. Significantly, overexpression of Gαs abolished the inhibitory effect of MGRN1 and decreased co-immunoprecipitation with MCRs, suggesting competition between MGRN1 and Gαs for binding to MCRs. Although all MGRN1s were located in the cytosol in the absence of MCRs, exon 12-containing isoforms accumulated in the nuclei upon co-expression with the receptors. Therefore, MGRN1 inhibits MCR signaling by a new mechanism involving displacement of Gαs, thus accounting for key features of the mahoganoid phenotype. Moreover, MGRN1 might provide a novel pathway for melanocortin signaling from the cell surface to the nucleus.

Introduction

The melanocortin receptors (MCRs)3 form a subfamily of class A G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) comprised of 5 members (MC1R–MC5R) (1). Their specific ligands, the melanocortins (MCs), are peptide hormones formed by proteolytic cleavage of proopiomelanocortin. The MC system regulates key physiological functions such as pigmentation, food intake, energy balance and body weight, cortisol production, sexual behavior, and exocrine secretion (2). The MCRs display partially overlapping but distinct pharmacological properties and expression profiles, and share key signaling properties including positive functional coupling to adenylyl cyclase (AC) via the Gs protein.

MCR signaling is tightly regulated by a variety of mechanisms best known for the MC1R (3). MC1R is expressed in epidermal melanocytes, where it regulates the amount and type of melanin pigments produced in response to α melanocyte-stimulating hormone (αMSH). Mammalian melanins are of two types: black-brown eumelanins and red-yellowish pheomelanins (4). Human MC1R is an unusually polymorphic gene (5), and several hypomorphic alleles are strongly associated with the complex RHC phenotype consisting of pheomelanin-rich red hair, abundant freckles, inefficient tanning upon sun exposure, high sensitivity to ultraviolet radiation-induced skin damage, and increased skin cancer risk (6). In mice, high MC1R signaling due to high levels of agonists (7) or gain-of-function mutations (8) leads to eumelanogenesis and dark coats. Conversely, absent or poor MC1R signaling due to loss-of-function mutations or expression of the endogenous inhibitor Agouti signal protein leads to pheomelanogenesis (9–11). Normal mouse hair has a characteristic banding pattern due to transient expression of the Agouti signal protein that switches pigment production from eumelanin to pheomelanin. Accordingly, mutations at the Agouti locus such as lethal yellow (Ay), that causes deregulated, ectopic and continuous expression of Agouti signal protein, produce a yellow coat color (12). Furthermore, Ay is associated with increased body size, obesity, and diabetes, due to interference of the Agouti signal protein with the central MC3R and MC4R receptors (13, 14). This shows that the MCRs share common regulatory mechanisms.

Genetic studies of pigment type switching in mice identified two accessory proteins for MC signaling (15, 16). One of them, Mahogunin ring finger-1 (MGRN1), was identified by positional cloning of mahoganoid (md) (16, 17), a mutation characterized by darkening of the back, ears, and tail of mice that also affects body weight and decreases the obesity associated with Ay. Moreover, md mice show alterations in the levels of expression and activity of mitochondrial proteins in the brain (18) that precedes the development of spongiform neurodegeneration with many features of prion diseases (19). Mutant mice also exhibit abnormal patterning of the left-right axis with congenital heart defects (20), thus suggesting a multiplicity of MGRN1 biological roles. Mouse MGRN1 and its human orthologue KIAA0544 contain a RING finger domain characteristic of E3 ubiquitin ligases, and the mouse protein has been shown to display ubiquitin ligase activity (19, 21). Ubiquitylation is a frequent modification of proteins, whereby the 76-amino acid ubiquitin (Ub) is coupled to the ϵ-amino group of a Lys residue in a protein substrate by the sequential actions of 3 enzymes: a Ub activating enzyme, a Ub conjugating enzymes, and Ub ligase (E3) (22). Its best characterized function is to target proteins for proteasomal degradation, but it also regulates other functions such as endocytosis, lysosomal targeting, nuclear export, DNA repair, histone remodeling, and activation of kinases and transcription factors (23). In addition, ubiquitylation of GPCRs or other proteins involved in GPCR-initiated pathways has important effects on their signaling (24, 25).

The coat color phenotype of md mice is very similar to MC1R gain-of-function mutants (15–17). Moreover, the coat of mice doubly mutant for the loss-of-function MC1Re allele and MGRN1md is identical to single MC1Re mutants (16), suggesting that MGRN1 lies functionally at the same level or upstream of MC1R. Thus, MGRN1 might inhibit MC1R signaling by regulating MC1R levels, subcellular distribution, or signaling (15).

We report here the characterization and functional analysis of human MGRN1. We show that human melanoma cells express 4 alternative splicing forms of MGRN1 similar to mouse cells (26). All the isoforms inhibit MC1R functional coupling to the cAMP cascade without decreasing MC1R plasma membrane density or intracellular stability. Inhibition is independent on receptor ubiquitylation or internalization, and might be specific for the MCR subfamily of GPCRs, as it is also observed for the MC4R but not for the β2-adrenergic receptor. Inhibition of MCR signaling might involve a new mechanism of uncoupling based on a physical interaction of the receptor and MGRN1 that would prevent productive association of the GPCR and Gs. We also show that 2 MGRN1 isoforms contain nuclear localization signals that are silent in the absence of MCRs but become activated in the presence of MC1R or MC4R, thus promoting a relocalization of MGRN1. Therefore, the MGRN1s might provide a new and still unexplored pathway between the MCRs and the nucleus.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

[125I]NDP-MSH (specific activity 2000 Ci/mmol) and a cAMP radioimmunoassay kit were from Amersham Biosciences. Lipofectamine 2000 was from Invitrogen. The following immunological reagents were used: anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal, anti-FLAG M2-peroxidase conjugate, anti-HA monoclonal, anti-HA-peroxidase conjugate, and anti-c-Myc rabbit polyclonal IgG from Sigma; anti-ubiquitin P4D1 monoclonal, anti-Gαs A-16 goat polyclonal, anti-actin (I-19) B, and anti-ERK2 rabbit polyclonal from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); and μMACs Protein G microbeads were from Miltenyi Biotec (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany).

Expression Constructs

All expression constructs were done on the pcDNA3 vector, and labeled with suitable epitopes if required. The ubiquitylation-null K0-MC1R mutant was obtained by site-directed mutagenesis, using the QuikChange XL Site-directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and FLAG epitope-labeled MC1R as template. The MGRN1s were amplified from cDNA obtained from human melanoma cells. Amplification products were cloned into pcDNA3. The c-Myc epitope sequence was then introduced in-frame at the 5′ end by PCR. The HA-MC4R, 3×HA-β2-adrenergic receptor, Gαs, and constitutively active Gαs (Q227L-Gαs) constructs were from the Missouri University of Science and Technology cDNA Resource Center (Rolla, MO). HA-TxA2R was a gift from Dr. C. Martinez (Centro de Hemodonacion, Hospital Reina Sofia, Murcia, Spain). Expression constructs for FLAG epitope-labeled p53 and the E3 Ub ligase Mdm2 were a gift from Drs. Xin Lu and Colin Goding (Ludwig Institute, Oxford, UK). All constructs were verified by automated sequencing in both strands.

Cell Culture and Transfection

Cell culture reagents were from TPP (Trasadingen, Switzerland) or Invitrogen. HEK293T cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate. HBL cells were grown in minimal essential medium. Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Functional Assays

Radioligand binding assays were done with 10−10 m [125I]NDP-MSH and increasing concentrations of unlabeled NDP-MSH up to 10−7 m when required (27). For cAMP production assays, cells were grown in 12-well plates, transfected as required, and serum-deprived for 24 h. They were then incubated with NDP-MSH (10−7 m), or 50 μm isoproterenol as appropriate for 30 min. The medium was aspirated and the cells quickly washed with 800 μl of ice-cold PBS. Cells were lysed with 200 μl of preheated 0.1 n HCl (70 °C) per well. The lysate was freeze-dried, washed with 100 μl of H2O, and freeze-dried again. cAMP was measured with a commercial radioimmunoassay. Parallel dishes were used for protein determination with the bicinchoninic acid method.

Electrophoresis and Western Blot

Transfected cells were washed twice with PBS and solubilized in 200 μl of solubilization buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 1% Igepal, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 mm iodoacetamide). When preservation of protein ubiquitylation was required, the solubilization buffer was supplemented with 100 mm N-ethylmaleimide. Samples were centrifuged (105,000 × g, 30 min) and a volume of supernatant containing 10 μg of protein was mixed (2:1 ratio) with sample buffer (180 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 15% glycerol, 9% SDS, 0.075% bromphenol blue, and 7.5% β-mercaptoethanol). Electrophoresis and Western blotting were performed as described (28, 29). Comparable loading was ascertained by stripping and reprobing the membranes with an anti-ERK2 antibody.

Immunoprecipitation Assays

HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-MC1R, HA-MC4R, or HA-TxA2R, alone or in combination with the Myc-labeled MGRN1s. 2 × 106 cells were washed twice with PBS, solubilized in 200 μl of solubilization buffer, and centrifuged (105,000 × g, 30 min). Supernatants were precleared with 40 μl of μMacs protein G microbeads slurry for 1 h. The mixture was then loaded onto a μColumn and the flow-through pre-cleared lysate was incubated with the required antibody (1–2 μg) and 50 μl of μMacs microbeads for 1 h at 4 °C. Samples were then applied to the column, extensively washed, and eluted with pre-heated (95 °C) electrophoresis sample buffer.

Confocal Microscopy

Cells grown on coverslips were transfected, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and permeabilized with 0.5% Igepal. Cells were then labeled with anti-FLAG monoclonal (1:7000) or anti-Myc polyclonal (1:2000), followed by Alexa 568- or Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibodies (emission was gated in ranges of 550–707 and 500–550 nm, respectively). Samples were mounted using a mounting medium from Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) and examined with a Leica laser scanning confocal microscope AOBS and software (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). The images were acquired in a 1024 × 1024 pixel format in sequential scan mode between frames to avoid cross-talk. The objective used was HCX PL APO CS ×63 and the pinhole value was 1, corresponding to 114.73 μm.

Subcellular Fractionation

HEK293T cells grown in 6-well plates were transfected as required. Monolayers were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, scraped in 2 ml of lysis buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mm NaCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 0.3% Igepal, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin), and incubated on ice for 30 min prior to centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min to pellet nuclei. The supernatants were used as the cytosolic fraction. Pellets were washed in lysis buffer without Igepal, resuspended in 10 μl of 40 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mm MgSO4, 1 mm CaCl2, and digested for 1 h at 37 °C with 1 unit of DNase (Promega). The reaction was stopped by addition of electrophoresis sample buffer at 95 °C. Aliquots of the cytosolic and nuclear fractions were electrophoresed, and Myc-MGRN1s were analyzed by immunoblotting. The purity of nuclear and cytosolic fractions was verified by the presence or absence of immunoreactive bands corresponding to endogenous Myc and by immunoblotting with an anti-β-actin antibody.

Determination of MC1R Intracellular Stability

HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-MC1R or the K0-MC1R mutant, alone or in combination with (+)S MGRN1. Protein synthesis was blocked with cycloheximide (0.1 mm). At selected times up to 8 h cells were harvested, lysed, and mixed with electrophoresis sample buffer. MC1R levels were estimated by Western blot. Quantification of band intensities was done with Image J version 1.29 (rbs.info. nih.gov/ij). Residual MC1R levels were plotted against the incubation time, and the plots were fitted to a single exponential decay for calculation of the half-life.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Human Melanoma Cells Express 4 MGRN Isoforms

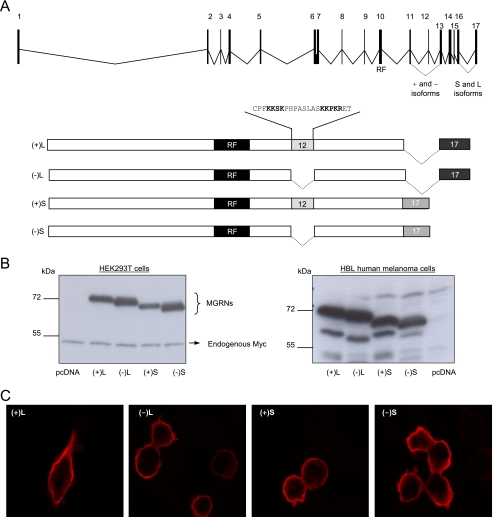

The mouse MGRN1 locus is comprised of 18 exons, and alternative splicing of exons 12 and 17 yields 4 isoforms (26). The human MGRN1 locus consists of 17 exons, and only 2 splice forms have been reported (ensembl). These forms arise from the use of alternative exon-exon junctions between exons 16 and 17, and the predicted proteins were identical up to amino acid residue 540. We designed PCR primers to amplify and clone these isoforms. Amplification of cDNA from two human melanoma cell lines yielded broad bands that were cloned, and individual clones were sequenced. In addition to the reported isoforms we found 2 new splice forms lacking exon 12 (GenBankTM accession numbers ABO69623 and ABO69624) (Fig. 1A). Therefore, human melanoma cells express 4 MGRN1 isoforms differing in the usage of exon 12 and in the junction of exons 16 and 17. The isoforms were named according to the length of the coding sequence specified by exon 17 (L for long, S for short) and the presence (+) or absence (−) of exon 12. Thus (+)L and (−)L are the isoforms with a long exon 17, containing or lacking exon 12, respectively, and (+)S and (−)S are the isoforms containing a short exon 17, with or without exon 12.

FIGURE 1.

Genomic structure and heterologous expression of human MGRN1 isoforms. A, genomic structure of human MGRN1 indicating exons (numbered boxes) and introns (lines) and scheme of MGRN1 protein isoforms generated by alternative splicing of exons 12 and 17. (+)- and (−)-forms contain or lack exon 12, respectively. L and S isoforms possess a long or shorter exon 17 generated by the use of an alternative exon junction. RF, C3HC4 RING finger domain (residues 278–316 encoded by exon 10). The peptide sequence encoded by exon 12, containing a bipartite nuclear localization signal highlighted with bold characters, is shown. B, Myc epitope-tagged MGRN1 isoforms were transfected in HEK293T cells and HA epitope-labeled forms were used in melanoma cells. MGRN1 expression was compared by Western blot. Cells transfected with empty vector (lanes labeled pcDNA) are shown as controls for specificity. For HEK cells, endogenous Myc provided an internal loading control. For HBL cells, blots were stripped and stained for ERK2 as loading control (not shown). C, confocal microscopy of HEK293T cells expressing Myc epitope-tagged MGRN1 isoforms. Transfected cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with αMyc.

The 4 MGRN1 isoforms were expressed in HEK293T cells or HBL human melanoma cells, and expression levels were compared by Western blot. For HEK293T cells, we used the Myc epitope-labeled constructs, and the comparatively weak endogenous Myc signal provided a convenient loading control. However, Myc amplification is a relatively common event in melanoma (30), and in preliminary experiments we observed high Myc expression in HBL cells. Therefore, these cells were transfected with HA epitope-labeled MGRNs to avoid artifacts. In both cell types, the relative electrophoretic mobility of the proteins was consistent with their predicted size, with the bigger and smaller size corresponding to the (+)L and (−)S forms, respectively (Fig. 1B). Comparable signal intensity for all MGRN1 forms indicated similar intracellular stabilities. Thus, the presence of exon 12 and the C-terminal sequence did not have a major impact on the turnover of MGRN1 isoforms.

Exon 12 codes for a 19-amino acid sequence with a canonical nuclear localization signal (Fig. 1A) consisting of 2 stretches of basic amino acids separated by a short intervening sequence (31). Therefore, it was of interest to compare the subcellular distribution of (+)- and (−)-isoforms. HEK293T cells expressing the different MGRN1s were examined in a confocal microscope. The staining pattern was similar in all cases, in that the 4 MGRNs were equally excluded from the nuclei and showed comparable staining intensities (Fig. 1C).

The MGRNs Inhibit MCR Signaling to the cAMP Pathway

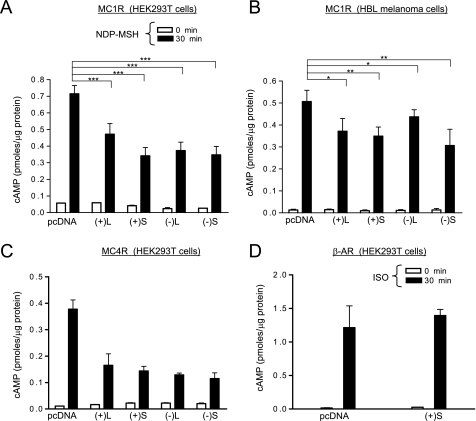

To study the effects of MGRN1s on MC1R signaling to cAMP, we coexpressed MC1R and each MGRN1 in HEK293T cells. Cells were stimulated with the α-MSH analogue [Nle4,d-Phe7]αMSH (NDP-MSH), and cAMP was measured. All MGRN1s decreased agonist-induced cAMP production by as much as 50% (Fig. 2A). Expression of the MGRN1s in HBL melanoma cells also decreased significantly the endogenous MC1R signaling (Fig. 2B). The apparently smaller inhibition compared with HEK cells likely resulted from lower transfection efficiency (10–20% assessed by confocal microscopy of cells transfected with a green fluorescent protein-MC1R fusion construct).

FIGURE 2.

MGRN1 inhibits functional coupling of MC1R and MC4R to the cAMP pathway. A, functional coupling of exogenous MC1R in the presence of MGRN1 isoforms. HEK293T transfected with MC1R and either empty pcDNA or the indicated MGRN1 isoforms were stimulated (10−7 m NDP-MSH, 30 min), lysed, and cAMP was measured. Empty bars correspond to controls and filled bars to stimulated cells. ***, p < 0.001. B, inhibition by MGRN1s of endogenous MC1R in HBL melanoma cells. Cells were transfected with empty vector or with MGRN1 isoforms, treated with vehicle or NDP-MSH as in panel A, and cAMP contents were determined. **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.1. C, functional coupling of MC4R is inhibited by MGRN1. HEK293T cells transfected with MC4R with or without the MGRN1s were analyzed for functional coupling as in A. D, lack of effect of MGRN1 on signaling from β2-adrenergic receptor (AR). HEK cells were co-transfected with β2-adrenergic receptor and empty vector or (+)S MGRN1, stimulated with isoproterenol (ISO, 50 μm, 30 min), and cAMP was measured. Error bars represent S.D., n > 5.

We next analyzed the specificity of MGRN1 action. In HEK cells transfected to express MGRN1 isoforms and MC4R, signaling was strongly inhibited (Fig. 2C). Conversely, (+)S did not inhibit signaling from the β2-adrenergic receptor. Indeed, cAMP levels after stimulation with isoproterenol were the same in cells expressing β2-adrenergic receptor alone or with (+)S MGRN1 (Fig. 2D). Therefore, the inhibitory effect of the MGRN1s was not restricted to MC1R, but might be specific of the MCR subfamily of GPCRs.

Inhibition of MCR Signaling by the MGRNs Is Independent on Receptor Down-regulation or Ubiquitylation

Mouse MGRN1 has E3 ubiquitin ligase activity (19, 21) and several GPCRs are known to undergo ubiquitylation followed by internalization and degradation in the proteasomes (32) or the lysosomes (33). Accordingly, it was conceivable that the MGRNs might down-regulate MCRs on the cell surface by promoting their internalization and/or degradation, thus inhibiting signaling (15). We compared the cell surface expression, internalization index, and intracellular stability of wild type (WT) MC1R in HEK cells expressing the receptor alone or with the MGRN1s. Moreover, we obtained a ubiquitylation-null MC1R mutant, K0-MC1R, by changing all intracellular Lys residues (Lys-65, Lys-226, Lys-238, and Lys-310) to Arg, which cannot act as a Ub acceptor. The behavior of this mutant was also compared with WT MC1R.

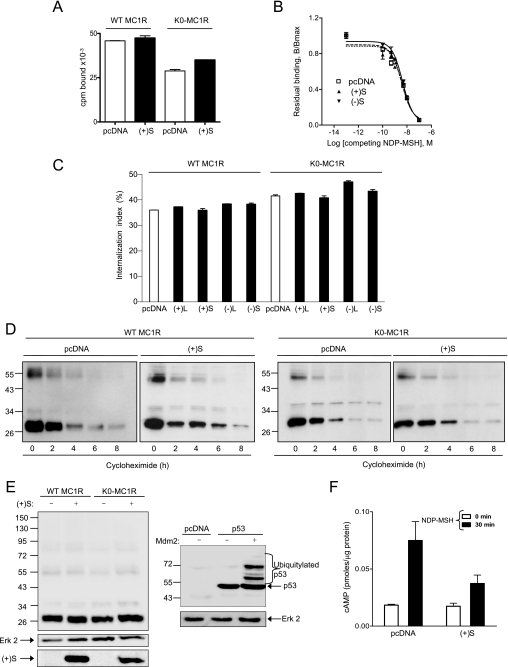

The density of MC1R receptors available on the plasma membrane was estimated by equilibrium binding assays. When cells were incubated with a subsaturating concentration of labeled agonist, (+)S MGRN1 did not decrease significantly the amount of specifically bound ligand for cells expressing either WT or K0-MC1R (Fig. 3A). Similar results were obtained for the other MGRN1 isoforms (not shown). This suggested that neither receptor number nor affinity for the ligand were altered by MGRN1s. This was confirmed by competition binding experiments (Fig. 3B). Equilibrium binding parameters obtained from displacement data were the same for cells expressing MC1R alone or with the MGRN1s. We next compared agonist-induced internalization. We used an acid wash protocol that distinguishes acid-sensitive radiolabeled agonist bound to the MC1R at the cell surface from acid wash-resistant internalized ligand (29). Only minor differences in the internalization rate were detected for WT or K0-MC1R, in the presence or absence of MGRN1s (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of MGRN1 on plasma membrane availability and intracellular stability of MC1R and inhibition of functional coupling of the K0-MC1R ubiquitylation null MC1R mutant. A, lack of down-regulation of NDP-MSH binding sites by MGRN1. HEK cells were transfected with WT or K0-MC1R and with (+)S MGRN1 (closed bars) or empty pcDNA3 (open bars). Cells were incubated with 10−10 m [125I]NDP-MSH for 1 h, washed, and bound radioactivity was counted. B, competition binding analysis for MC1R in the presence of two MGRN1 variants. Cells expressing MC1R alone or with (+)S or (−)S were incubated with 10−10 m [125I]NDP-MSH and increasing concentrations of unlabeled ligand, as indicated. The specifically bound radioactivity was measured. Results are given as % maximal binding in the absence of competitor. C, effect of MGRN1 isoforms on MC1R internalization. HEK293T cells were transfected with WT or K0-MC1R and the indicated MGRN1 isoforms (closed bars) or empty pcDNA as control (open bars). Transfected cells were incubated with [125I]NDP-MSH for 1.5 h. The amount of internalized radioligand was determined by an acid-wash procedure and an internalization index (percentage of agonist internalized relative to total binding) was calculated. D, effect of (+)S on the intracellular stability of MC1R. HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-tagged WT or K0-MC1R with or without (+)S MGRN1 were treated with 10−4 m cycloheximide and harvested at the times shown. Solubilized cell extracts were electrophoresed and immunoblotted with αFLAG. A representative blot is shown out of three experiments with similar results. E, comparable electrophoretic pattern of WT and K0-MC1R. HEK293T cells transfected to express WT or mutant MC1R with or without Myc epitope-labeled (+)S MGRN1 were analyzed for MC1R by Western blot (left blot, upper). Blots were stripped and probed for ERK2 as a loading control (left blot, middle), and for MGRN1 as a control for comparable expression of (+)S (left blot, lower). As a positive control for recovery and detection of the ubiquitylated species, HEK cells were transfected with empty vector or FLAG-labeled p53 alone or with its E3 Ub ligase Mdm2. Cell extracts were analyzed for p53 to detect ubiquitylated forms (right blot, upper) and for ERK2 (right gel, lower) as a loading control. F, functional coupling of K0-MC1R in the presence or absence of (+)S MGRN1. HEK293T transfected with K0-MC1R and empty vector (pcDNA) or (+)S were stimulated (10−7 m NDP-MSH, 30 min), and cAMP was measured. Empty bars correspond to vehicle-treated controls and filled bars to agonist-stimulated cells. Error bars represent S.D., n > 5.

To analyze the effect of MGRN1 on the rate of intracellular degradation of the receptor, HEK cells expressing WT or K0-MC1R alone or with (+)S MGRN1 were treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide. Residual MC1R levels at different times after addition of the antibiotic were compared by Western blot (Fig. 3D). Band intensities were quantified by densitometry and plotted against time, and the half-life of the protein was determined from these plots. MGRN1 did not destabilize the MC1R, as shown by a slightly higher half-life in the presence of (+)S, for either WT or K0-MC1R (WT, 3.5 h in the presence of MGRN1, versus 3.2 h in controls; K0-MC1R, 3.7 h with MGRN1 and 2.7 h in controls). Identical results were obtained for other MGRN1 isoforms. These data demonstrated that inhibition of MC1R signaling by the MGRN1s was not dependent on receptor down-regulation as a result of internalization or degradation.

Inspection of the gels shown in Fig. 3D failed to reveal clear differences in the electrophoretic pattern of WT and K0-MC1R, or high molecular weight bands indicative of the ubiquitylated species. Absence of detectable ubiquitylated MC1R forms was confirmed by comparing side-by-side the electrophoretic behavior of WT and K0-MC1R expressed alone or in combination with (+)S. The pattern was similar in all cases, with two major 30- and 36-kDa bands corresponding to the de novo and glycosylated species, and minor bands of SDS-resistant dimers and oligomers (5, 28) (Fig. 3E, left gel). The slightly higher steady-state MC1R protein levels in extracts from cells expressing (+)S were consistent with the small increases in half-life obtained in the presence of the MGRN1 (Fig. 3D). As a positive control for extraction and detection of ubiquitylated proteins, we used p53 expressed in combination with the E3 Ub ligase Mdm2 (34). The successful identification of Mdm2-dependent p53 ubiquitylation confirmed the suitability of our sample preparation protocol (Fig. 3E, right gel).

These results suggested that receptor ubiquitylation was not a requisite for inhibition of signaling. To confirm this point, we tested the effect of MGRN1 on signaling from the ubiquitylation incompetent K0-MC1R mutant. (+)S MGRN1 decreased signaling from K0-MC1R at least as potently as from WT (Fig. 3F).

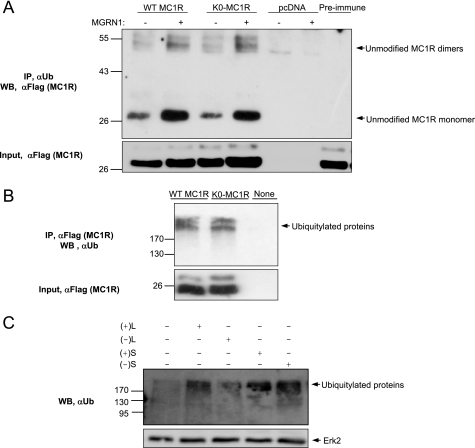

As a final evidence for the failure of MGRN1 to ubiquitylate MC1R, we analyzed receptor recognition by an anti-Ub (αUb) antiserum. We co-expressed (+)S and FLAG epitope-labeled WT or K0-MC1R. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with αUb or anti-FLAG (αFLAG) antisera, and the pellets were analyzed for MC1R by Western blot using αFLAG or for ubiquitylated proteins with αUb. αUb specifically immunoprecipitated MC1R bands corresponding to the non-ubiquitylated monomeric and dimeric species, according to their size and presence for both WT and K0-MC1R (Fig. 4A). Therefore, MC1R was not ubiquitylated by MGRN1 but it interacted with an ubiquitylated protein. Interestingly, this interaction appeared enhanced by MGRN1 as shown by higher amounts of co-precipitated receptor in cells co-expressing MC1R and MGRN1 compared with MC1R alone. Association of MC1R with ubiquitylated partners was further shown by immunoprecipitation of high Mr ubiquitylated species by αFLAG in extracts from cells transfected with WT or K0-MC1R (Fig. 4B). The identification of the ubiquitylated species again confirmed the preservation of protein-bound Ub chains under our experimental conditions. Finally, although the MGRN1s did not ubiquitylate MC1R, they likely displayed Ub ligase activity as suggested by increased levels of high Mr ubiquitylated species in cells transfected with the different isoforms, compared with cells transfected with empty vector (Fig. 4C). Taken together, the results shown in Figs. 3 and 4 demonstrate that the effects of the MGRNs on MC1R signaling were not dependent on receptor ubiquitylation.

FIGURE 4.

MGRN1 does not ubiquitylate MC1R expressed in HEK293T cells. A, immunoprecipitation of native MC1R by an antibody against Ub. HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged WT MC1R or K0-MC1R, alone or with (+)S. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoprecipitation with an anti-Ub antibody (αUb), followed by immunoblotting for MC1R with anti-FLAG (upper blot). As controls for specificity, cells transfected with empty pcDNA were used, and lysates from cells expressing FLAG-tagged WT MC1R were treated with a preimmune IgG. Untreated aliquots of cell extracts were electrophoresed in parallel and blotted for MC1R with αFLAG as a control for comparable input (lower blot). B, immunoprecipitation of ubiquitylated proteins with an antibody to MC1R. Extracts from HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-tagged WT MC1R or K0-MC1R were immunoprecipitated for MC1R with anti-FLAG and the pellets were Western blotted with αUb. Comparable input was ascertained by Western blot (WB) with αFLAG. C, increased protein ubiquitylation in cells expressing the MGRN1s. HEK293T cells transfected with empty vector or with MGRN1 isoforms were analyzed for ubiquitylated proteins by Western blot with αUb. Comparable loading was verified by reprobing the stripped membrane with αERK2 (lower blot).

MGRN1 Acts Upstream of Gαs Binding to and Activation of AC and Competes with Gs for Binding to the MCR

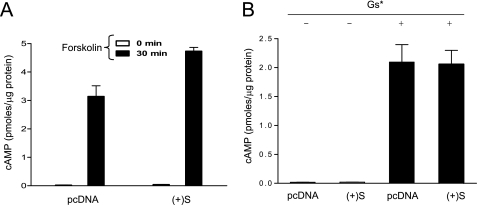

Because down-regulation of cell surface MCRs or receptor degradation were not the mechanisms accounting for inhibition of signaling, we tried to identify the steps of the cAMP cascade targeted by the MGRN1s. The cAMP pathway is initiated by interaction of activated receptors with the Gs αβγ heterotrimer, followed by GTP loading into the Gαs subunit, dissociation of GTP-bound Gαs from the βγ-dimer, and activation of AC by free Gαs (35). HEK cells expressing (+)S MGRN1 responded to the AC activator forskolin with cAMP increases higher than control cells (Fig. 5A). Thus, AC activity was not inhibited by MGRN1. Next, we tested the effect of MGRN1 on a constitutively active Gαs mutant. This mutant exists as a GTP-bound monomer, which binds and stimulates AC in the absence of active GPCR partners (36). When expressed in HEK293T cells, the mutant activated strongly cAMP synthesis and was not inhibited by (+)S MGRN1 (Fig. 5B). Therefore, MGRN1 did not interfere with binding of active Gαs to AC.

FIGURE 5.

MGRN1 does not inhibit adenylyl cyclase activation by forskolin or a constitutively active Gs protein. A, cAMP levels in HEK293T cells expressing MC1R alone (empty bars) or with (+)S (filled bars), following stimulation with forskolin (10−5 m, 30 min). B, cAMP levels in HEK cells expressing a constitutively active Gαs mutant (Gs*) alone or in combination with (+)S MGRN1. Error bars represent S.D., n = 5.

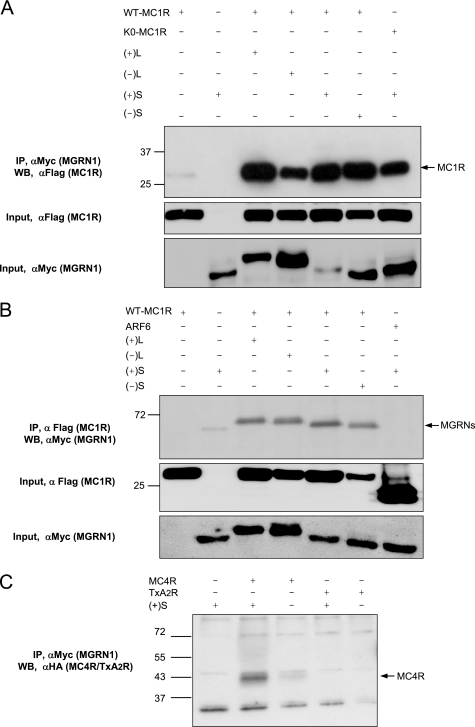

On the other hand, because the MGRN1s did not inhibit signaling from the β2-adrenergic receptor, it appears that they did not block the Gs heterotrimer in an inactive state, nor did they alter the functionality of RGS proteins. Taken together, the observations reported thus far showed that MGRN1 should act downstream of the formation of the hormone-receptor complex but upstream of the Gαs binding to and activation of AC. We hypothesized that MGRN1s might block activation of resting Gs by competing with this protein for binding to the MCRs. Several predictions could be used to test this model: (i) MCRs and MGRN1s should interact physically; (ii) overexpression of Gαs should displace MGRN1s from MCRs; and (iii) overexpression of Gαs should relieve inhibition of signaling. To test these predictions, the Myc-MGRN1s and FLAG-MC1R were co-expressed in HEK293T cells. Extracts were immunoprecipitated for MGRN1 with anti-Myc (αMyc), and pellets were analyzed for MC1R with αFLAG. WT and K0-MC1R co-immunoprecipitated efficiently with all MGRN1 isoforms (Fig. 6A). We obtained the same pattern when MC1R was immunoprecipitated with αFLAG and the pellets were probed for MGRN1s with αMyc (Fig. 6B). We analyzed the specificity of the receptor-MGRN1 interaction by immunoprecipitation of extracts from cells co-expressing (+)S MGRN1 and MC4R or a thromboxane receptor (TxA2R) (Fig. 6C). MC4R but not TxA2R co-precipitated with MGRN1.

FIGURE 6.

Efficient co-immunoprecipitation of MC1R and MC4R and MGRN1 isoforms. A, interaction between FLAG-MC1R and Myc-MGRN1 isoforms. Extracts from HEK cells expressing WT MC1R or the K0-MC1R mutant, alone or in combination with the MGRN1s were immunoprecipitated (IP) for the MGRN1s with αMyc and Western blotted (WB) for MC1R with αFLAG. Extracts from cells expressing MC1R or S(+) alone were used as negative controls. Input controls were performed by Western blotting aliquots of the cell lysates, with detection with αFLAG for MC1R (middle blot) or αMyc for MGRN1 (lower blot). B, same as in A, except that extracts were immunoprecipitated for MC1R with αFLAG and immune pellets were blotted for MGRN1 with αMyc. As a further control for specificity, cells expressing the FLAG epitope-labeled ADP-ribosylation factor ARF6 were also analyzed. An input control was performed by blotting aliquots of cell lysates with αFLAG and αMyc. C, co-immunoprecipitation of MGRN1 and MC4R, but not TxA2R. HEK cells were transfected with HA epitope-labeled MC4R or TxA2R, alone or with (+)S. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated for the MGRN1 and the pellets blotted for the receptors with an αHA antibody.

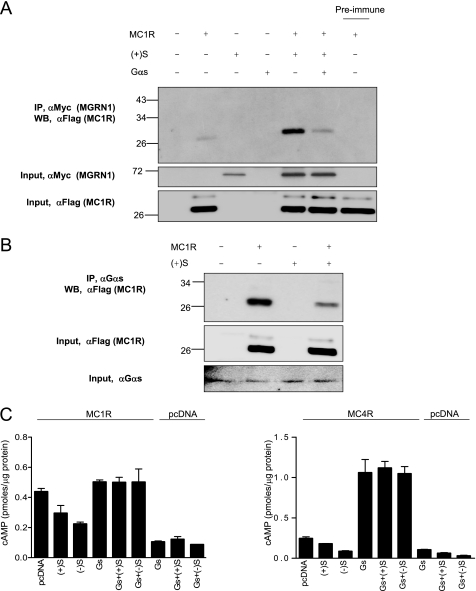

We next analyzed the effect of Gαs overexpression on the interaction of MGRN1 and MC1R. HEK cells were transfected to express MC1R, Myc epitope-tagged (+)S, or native Gαs, alone or in suitable combinations. Extracts were immunoprecipitated for MGRN1 with αMyc and co-precipitated MC1R was analyzed by Western blot with αFLAG (Fig. 7A). The amount of MC1R co-immunoprecipitated with (+)S MGRN1 decreased markedly upon transfection with Gαs. Similar results were obtained with other MGRN1 isoforms (not shown). Moreover, when we immunoprecipitated extracts of cells expressing MC1R with an anti-Gαs antiserum, MC1R was detected in the pellets, indicative of its association with endogenous Gαs (Fig. 7B). Co-transfection of MC1R and (+)S decreased the amount of MC1R co-immunoprecipitated with Gαs, consistent with competition between Gs and MGRN1 for binding to MC1R. Finally we tested the effects of MGRN1 on cAMP production in cells expressing MC1R or MC4R alone, or with Gαs (Fig. 7C). Increasing the concentration of Gαs by transfection blocked the inhibitory action of the MGRN1s. These data supported a model for MGRN1 action based on competitive inhibition of MCR coupling to Gs. This mechanism would be reminiscent of the mode of action of arrestins (37). However, failure to inhibit β2-adrenergic receptor signaling or to interact with the TxA2R suggests that MGRN1 could be less promiscuous than arrestins. In this respect, it will be very interesting to assess carefully the specificity of the MGRN1s by testing their effects on receptors more closely related to MC1R than the β2-adrenergic receptor, such as endothelial differentiation GPCRs, receptors for endogenous cannabinoids, adenosine binding receptors (38), or MCRs other than MC1R and MC4R. In particular, it will be worth analyzing MGRN1md mice for alterations in glucocorticoid levels or in response to stress conditions, which would point to a regulatory role on MC2R. This possibility is further suggested by the strong MGRN1 expression observed in the kidney (17).

FIGURE 7.

Decreased interaction of MGRN1 and MCRs in the presence of excess Gαs. A, expression of exogenous Gαs inhibits co-precipitation of MGRN1s and MC1R. Myc-tagged (+)S was expressed in HEK293T cells alone or in combination with FLAG-MC1R and exogenous Gαs, as indicated. Extracts were immunoprecipitated (IP) for MGRN1 with αMyc, and the immune pellets were analyzed for MC1R by Western blot (WB) with αFLAG. The experiment was performed after stimulation with NDP-MSH to encourage interaction between MC1R and Gs, and was repeated 3 times with similar results. Input controls consisted of blots of suitable aliquots of cell lysates with αMyc (for detection of MGRN1, middle blot) or αFLAG (for detection of MC1R, lower blot). B, expression of (+)S MGRN1 disrupts the interaction of endogenous Gαs and MC1R. Extracts from HEK cells transfected with FLAG-MC1R with or without (+)S MGRN1 were immunoprecipitated for endogenous Gαs and the amount of MC1R associated with the G protein was estimated by Western blotting the pellets with αFLAG. Input controls consisted of blots of suitable aliquots of cell lysates with αFLAG (for detection of MC1R, middle blot) or αGαs (lower blot). C, overexpression of Gαs rescues the MCRs from inhibition by MGRN1s. HEK cells were transfected to express MC1R (left graph) or MC4R (right graph), with or without S MGRN1 isoforms and/or Gαs, as indicated. Cells were stimulated with NDP-MSH, lysed, and cAMP was determined.

MGRN1 Isoforms Containing Exon 12 Are Targeted to the Nucleus by the MCRs

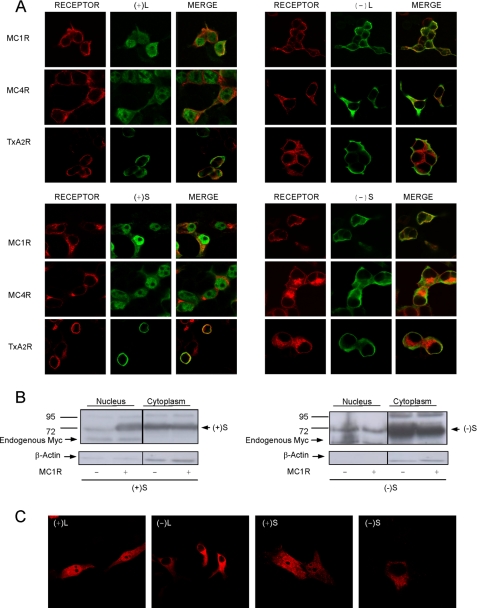

To obtain further evidence of an MCR-MGRN1 interaction, cells co-expressing MC1R or MC4R and the MGRN1s were analyzed by confocal microscopy, because a physical interaction would result in detectable co-localization. Surprisingly, a very different pattern was observed for (−)-isoforms compared with exon 12-expressing (+)-isoforms (Fig. 8A). The staining pattern of (−)-forms was the same as in the absence of receptors (Fig. 1C), with labeling of the cytoplasm and plasma membrane. Conversely, the (+)-MGRN1 forms were found preferentially in the nucleus when co-expressed with MCRs. Nuclear staining was specific because: (i) it was only observed for (+)-forms; (ii) intranuclear structures corresponding to nucleoli were not labeled; and (iii) relocalization of (+)-MGRN1s from the cytosol to the nucleus was not triggered by the TxA2R. Therefore, nuclear localization signals of exon 12 were silent in cells expressing the MGRN1s alone but became active in the presence of MCRs.

FIGURE 8.

Nuclear targeting of (+)-MGRN1 isoforms by MC1R and MC4R. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with MC1R, MC4R, or TxA2R and with Myc epitope-labeled MGRN1 isoforms, as indicated. The distribution of the proteins was visualized by confocal microscopy. Receptors are shown in red (left panel of each group). Middle panels, Myc-MGRN1s shown in green. The right columns in each group show the overlays. B, effect of MC1R on the presence of S isoforms in nuclear extracts. HEK cells transfected with Myc-labeled (+)S or (−)S MGRN1, alone or with MC1R, were fractionated into cytosolic and nuclear fractions. The fractions were analyzed for MGRN1 by blotting with αMyc. Also, blots were stripped and stained for β-actin. C, nuclear accumulation of (+)-MGRN1s in human melanoma cells. HBL cells were transfected with HA-labeled MGRN1s, permeabilized, stained with αHA, and analyzed by confocal microscopy.

To confirm these findings, we isolated nuclei from cells expressing (+)S or (−)S. The presence of MGRN1 in nuclear and cytosolic fractions was compared by Western blot (Fig. 8B). Nuclear (+)S increased dramatically upon coexpression with MC1R, consistent with confocal microscopy images. The purity of the fractions was shown by the presence of an endogenous Myc signal exclusively in the nuclear fraction and by the higher intensity of the β-actin signal in cytosolic fractions (Fig. 8B, left). On the other hand, (−)S MGRN1 was preferentially found in the cytosol and expression of MC1R did not increase its levels in the nucleus (Fig. 8B, right). Similar results were obtained for (−)L and (+)L isoforms (not shown).

Finally, we assessed the effects of physiological levels of endogenous MC1R on the subcellular distribution of the MGRN1s. HBL human melanoma cells expressing 3500 NDP-MSH binding sites/cell (39) were transfected with HA-labeled MGRN1 isoforms and observed at the confocal microscope. The (+)-forms were detected in the nuclei and cytosol, whereas (−)-forms were found in the cytoplasm and in association with the plasma membrane (Fig. 8C), but seemed excluded from the nuclei. This finding suggests that physiological levels of the MC1R might be sufficient to target (+)-MGRN1s to the nucleus.

The occurrence of MGRN1 isoforms with different subcellular compartmentalization suggests that the various MGRNs may have partially non-redundant functions, a possibility highlighted by recent studies (40). All MGRN1 isoforms were approximately equipotent in inhibiting signaling from MC1R or MC4R to cAMP production. However, in addition to inhibiting MCR signaling on the cell surface, (+)-MGRN1s but not the (−)-forms might display specific functions within the nucleus. In keeping with this possibility ubiquitylation regulates the stability or transactivating activity of many transcription factors (41), at least two of which, p53 and MITF, play key roles in the regulation of pigmentation (42, 43). Therefore, it is possible that (+)-MGRN1 isoforms might fulfill specific functions not present in (−)-forms by providing a novel signaling pathway from the plasma membrane to the cell nucleus. A key role of the (+)-MGRN1s in MCR signaling is further suggested by the observation that these isoforms are normally expressed at much higher levels than the (−)-forms in normal adult mouse skin (26). However, this possibility must be taken with caution until putative nuclear targets of MGRN1 are identified.

Conclusions

We have shown that all the MGRN1 isoforms inhibited cAMP production in HEK293T cells expressing MC1R or MC4R, and in human melanoma cells expressing endogenous MC1R. No evidence of MC1R ubiquitylation was found, and inhibition did not depend on receptor down-regulation. Moreover, the MGRN1s were equally active on WT MC1R and the ubiquitylation-incompetent mutant. Thus, inhibition of MCR signaling by the MGRN1s should be due to a reduction of the signaling potential, likely by interference with binding of the agonist-receptor complex to Gαs. In support of this hypothesis, increasing the Gαs intracellular concentration by transfection with an expression construct decreased MGRN1 inhibition. More conclusively, the amount of MC1R that co-immunoprecipitated with MGRN1 decreased when the concentration of Gαs increased. However, most of our results were obtained under conditions of protein overexpression following transient transfections of melanoma or heterologous cells. Therefore, the proposed mechanism should be confirmed, ideally by knocking down endogenous MGRN1 expression with specific small interfering RNAs. In any case, our observation that MGRN1s inhibit MC1R and MC4R signaling accounts well for some phenotypic characteristics of MGRN1 mutant mice. By relieving the inhibition of MC1R signaling in melanocytes, hypomorphic MGRN1 alleles would increase the ratio of eumelanin to pheomelanin pigments, thus promoting darker furs. A similar effect on signaling by hypothalamic MC4R would decrease body weight. It is likely that an effect of the MGRN1s on MC3R would contribute to the control of food intake, energy expenditure, and body mass, but a definite assessment of this possibility must wait until the effects of MGRN1 on MC3R signaling are studied. On the other hand, the relationship of our findings with other aspects of the MGRN1md phenotype is less clear-cut. MC4R expression is relatively high in the heart (44), thus suggesting that altered MC4R signaling might contribute to the congenital heart defects in MGRN1md mice. However, a role of MC4R in heart development has not yet been reported. In addition, it has been suggested that the spongiform degeneration found with a graded penetrance in the MGRN1 allelic series might be related to a general dysregulation of endosomal trafficking as a result of ubiquitylation of TSG101, a key component of the endosomal sorting complex required for transport-I (21). The relative contributions to the MGRN1md phenotype of alterations in endosomal trafficking versus MCR signaling remain unknown.

Furthermore, two MGRN1 isoforms were targeted to the nucleus upon interaction with MCRs. This might provide a new signaling mechanism from a GPCR to the nucleus. Identification of the putative nuclear targets of the MGRN1s might yield new insights on the regulation of processes such as skin pigmentation, neurodegeneration and regulation of food intake, energy homeostasis, and body weight.

This work was supported in part by Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología (CICYT), Spain, Grant SAF2006-11206, Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional funds (European Community), Comunidad Autonoma Region de Murcia Grant 464/2008, and the Plan de Ciencia y Tecnología 2007/10.

- MCR

- melanocortin receptor

- AC

- adenylyl cyclase

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- MC

- melanocortin

- αMSH

- α melanocyte-stimulating hormone

- MGRN1

- mahogunin RING finger 1

- NDP-MSH

- norleucine 4 d-phenylalanine 7-melanocyte-stimulating hormone

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- TxA2R

- thromboxane receptor

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- WT

- wild type

- E3

- ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney.

REFERENCES

- 1.Starowicz K., Przewłocka B. (2003) Life Sci. 73, 823–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gantz I., Fong T. M. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 284, E468–E474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.García-Borrón J. C., Sánchez-Laorden B. L., Jiménez-Cervantes C. (2005) Pigment Cell Res. 18, 393–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyamura Y., Coelho S. G., Wolber R., Miller S. A., Wakamatsu K., Zmudzka B. Z., Ito S., Smuda C., Passeron T., Choi W., Batzer J., Yamaguchi Y., Beer J. Z., Hearing V. J. (2007) Pigment Cell Res. 20, 2–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pérez Oliva A. B., Fernéndez L. P., Detorre C., Herráiz C., Martínez-Escribano J. A., Benítez J., Lozano Teruel J. A., García-Borrón J. C., Jiménez-Cervantes C., Ribas G. (2009) Hum. Mutat. 30, 811–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rees J. L. (2004) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75, 739–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geschwind I. I. (1966) Endocrinology 79, 1165–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robbins L. S., Nadeau J. H., Johnson K. R., Kelly M. A., Roselli-Rehfuss L., Baack E., Mountjoy K. G., Cone R. D. (1993) Cell 72, 827–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bultman S. J., Michaud E. J., Woychik R. P. (1992) Cell 71, 1195–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu D., Willard D., Patel I. R., Kadwell S., Overton L., Kost T., Luther M., Chen W., Woychik R. P., Wilkison W. O. (1994) Nature 371, 799–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller M. W., Duhl D. M., Vrieling H., Cordes S. P., Ollmann M. M., Winkes B. M., Barsh G. S. (1993) Genes Dev. 7, 454–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barsh G. S. (2006) in The Pigmentary System (Nordlund J, Boissy R., Hearing V., King R., Oetting W., Ortonne S. P. eds) pp. 395–409, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adan R. A., Kas M. J. (2003) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 24, 315–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barsh G. S., He L., Gunn T. M. (2002) J. Recept. Signal. Transduct. Res. 22, 63–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He L., Eldridge A. G., Jackson P. K., Gunn T. M., Barsh G. S. (2003) Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 994, 288–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller K. A., Gunn T. M., Carrasquillo M. M., Lamoreux M. L., Galbraith D. B., Barsh G. S. (1997) Genetics 146, 1407–1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phan L. K., Lin F., LeDuc C. A., Chung W. K., Leibel R. L. (2002) J. Clin. Invest. 110, 1449–1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun K., Johnson B. S., Gunn T. M. (2007) Neurobiol. Aging 28, 1840–1852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He L., Lu X. Y., Jolly A. F., Eldridge A. G., Watson S. J., Jackson P. K., Barsh G. S., Gunn T. M. (2003) Science 299, 710–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cota C. D., Bagher P., Pelc P., Smith C. O., Bodner C. R., Gunn T. M. (2006) Dev. Dyn. 235, 3438–3447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim B. Y., Olzmann J. A., Barsh G. S., Chin L. S., Li L. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 1129–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hershko A., Ciechanover A. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 425–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weissman A. M. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 169–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shenoy S. K., Barak L. S., Xiao K., Ahn S., Berthouze M., Shukla A. K., Luttrell L. M., Lefkowitz R. J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 29549–29562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wojcikiewicz R. J. (2004) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 25, 35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bagher P., Jiao J., Owen Smith C., Cota C. D., Gunn T. M. (2006) Pigment Cell Res. 19, 635–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiménez-Cervantes C., Germer S., González P., Sánchez J., Sánchez C. O., García-Borrón J. C. (2001) FEBS Lett. 508, 44–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sánchez-Laorden B. L., Sánchez-Más J., Martínez-Alonso E., Martínez-Menárguez J. A., García-Borrón J. C., Jiménez-Cervantes C. (2006) J. Invest. Dermatol. 126, 172–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sánchez-Laorden B. L., Jiménez-Cervantes C., García-Borrón J. C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3241–3251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraehn G. M., Utikal J., Udart M., Greulich K. M., Bezold G., Kaskel P., Leiter U., Peter R. U. (2001) Br. J. Cancer 84, 72–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lange A., Mills R. E., Lange C. J., Stewart M., Devine S. E., Corbett A. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5101–5105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin N. P., Lefkowitz R. J., Shenoy S. K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 45954–45959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shenoy S. K., McDonald P. H., Kohout T. A., Lefkowitz R. J. (2001) Science 294, 1307–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brooks C. L., Gu W. (2006) Mol. Cell 21, 307–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cabrera-Vera T. M., Vanhauwe J., Thomas T. O., Medkova M., Preininger A., Mazzoni M. R., Hamm H. E. (2003) Endocr. Rev. 24, 765–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muca C., Vallar L. (1994) Oncogene 9, 3647–3653 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luttrell L. M., Lefkowitz R. J. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 455–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fredriksson R., Lagerström M. C., Lundin L. G., Schiöth H. B. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 63, 1256–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Más J. S., Gerritsen I., Hahmann C., Jiménez-Cervantes C., García-Borrón J. C. (2003) Pigment Cell Res. 16, 540–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiao J., Kim H. Y., Liu R. R., Hogan C. A., Sun K., Tam L. M., Gunn T. M. (2009) Genesis 47, 524–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muratani M., Tansey W. P. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 192–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cui R., Widlund H. R., Feige E., Lin J. Y., Wilensky D. L., Igras V. E., D'Orazio J., Fung C. Y., Schanbacher C. F., Granter S. R., Fisher D. E. (2007) Cell 128, 853–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murakami H., Arnheiter H. (2005) Pigment Cell Res. 18, 265–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mountjoy K. G., Jenny Wu C. S., Dumont L. M., Wild J. M. (2003) Endocrinology 144, 5488–5496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]