Abstract

Tumor progression and metastasis depend on the ability of cancer cells to initiate angiogenesis to ensure delivery of oxygen, nutrients, and growth factors to tumor cells and provide access to the systemic circulation. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) can activate expression of a broad range of genes that mediate many of the adaptive responses to decreased oxygen concentration, such as enhanced glucose uptake and formation of new blood vessels. Acting through Plexin-B1 on endothelial cells, Semaphorin 4D (Sema4D) has been shown to promote angiogenesis and enhance invasive growth and proliferation in some tumors. Here we show that the gene for Sema4D, the product of which is elevated in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cells, contains upstream hypoxia response elements (HRE) and is strongly induced in hypoxia in a HIF-1-dependent manner. Knocking down Sema4D expression with short hairpin (sh) RNA reduces in vitro endothelial cell migration and growth and vascularity of HNSCC xenografts expressing a degradation resistant HIF-1α subunit. We also demonstrate a correlation between HIF-1 activity and Sema4D expression in HNSCC specimens. These findings indicate that Sema4D is induced by hypoxia in a HIF-1-dependent manner and influences endothelial cell migration and tumor vascularity. Expression of Sema4D may be a strategy by which carcinomas promote angiogenesis and therefore could represent a therapeutic target for these malignancies.

Introduction

The semaphorins and plexins comprise a family of proteins shown to control proliferation and survival in many different cells and tissues, including the nervous system, the immune system (1), and the vasculature (2). Such diversity of function likely arises as a result of homology with the scatter factor family of proteins, which are known to participate in branching morphogenesis and normal and aberrant motility in numerous cell types (3). Currently, more than 20 semaphorins have been identified that are grouped into eight classes (4). Plexins, which are receptors for the semaphorins, share homology in their extracellular segment with the scatter factor receptors c-Met and RON. In humans, at least nine plexins have been identified and grouped into four families, A through D, most of which have been shown to mediate neuronal cell adhesion and axon guidance (5). We have demonstrated that Semaphorin 4D (Sema4D)2 is overexpressed by many different aggressive carcinomas, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), and that its activity on endothelial cells, which express its receptor Plexin-B1, promotes enhanced growth and vascularity of tumor xenografts in vivo (6). Why Sema4D is overexpressed in so many different tumor types remains unknown, but like other pro-angiogenic factors, plexins and semaphorins may be regulated by changes in oxygen tension (7).

The hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) transcriptional complex is the ‘master control switch’ for hypoxia. Initially identified by Semenza and colleagues in the early 1990s, HIF-1 is composed of two polypeptides: HIF-1α and HIF-1β (the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator or ARNT) (8). HIF-1β is expressed constitutively but HIF activity is regulated at the post-transcriptional level by oxygen-dependent hydroxylation of specific proline residues on the α subunit by the prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins (PHD). When hydroxylated, HIF α members are targeted for proteasome degradation by complexing with the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor protein, a component of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (9). In rapidly growing tumors or following a series of genetic mutations, VHL-mediated degradation of HIF-1α can be lost. HIF-1 will then bind to hypoxia response elements (HRE) in the promoter and activate expression of a broad range of genes that mediate the adaptive responses to decreased oxygen concentration, such as enhanced glucose uptake and the formation of new blood vessels via proliferation and migration of endothelial cells toward the developing tumor (10). This latter response is influenced by increased production of pro-angiogenic proteins such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

Here we show that HNSCC cell lines exhibit an enhanced hypoxic response compared with control epithelial cell lines, as evidenced by high levels of HIF-1α protein and transcriptional activity, and a corresponding HIF-1-dependent increase in Sema4D mRNA and protein. We identify HRE upstream of the Sema4D gene in a potential promoter region that bind HIF-1. Expression of the HIF-1α oxygen-dependent degradation domain mutant (HIF-1α mODD) in cells resulted in elevated Sema4D levels and an increased ability to induce endothelial cell migration in vitro and enhanced growth and vascularity of tumor xenografts in vivo, while knockdown of Sema4D with short hairpin (sh) RNA significantly attenuated these responses. We also show that Sema4D expression in HNSCC correlates with areas of tumor that exhibit enhanced HIF-1α activity. Taken together, these findings suggest that along with VEGF and other factors, the class IV semaphorins may be part of the hypoxia adaptive response, which is dysregulated in HNSCC.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

HNSCC lines 12 and 13 and HaCaT and HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 250 ng/ml amphotericin B. The HNSCC cells have been previously described (11). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were cultured in Endothelial Cell Basal Media (EBM, Clonetics, Walkersville, MD).

Immunoblot Analysis

Cells were lysed, and 100 μg of protein subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as previously described (12). Following gel electrophoresis, a transfer was done onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon P, Millipore, Bedford, MA), which was incubated with the appropriate antibodies: Sema4D, HIF-1α, and HIF-1β (1:100 dilution, BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA); Glut-1 (1:100 dilution, Abcam, Cambridge, MA); anti-tubulin (1:100 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Band intensities were determined from scanned blots using Image J (NIH), with fold increases noted relative to the appropriate controls, normalized to tubulin.

Luciferase Assay

The indicated cell lines were transfected with control DNA or a luciferase reporter plasmid containing the wild-type or mutated VEGF promoter using Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or electroporated in a Nucleofector machine (Amaxa) and subjected to a luciferase assay (Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System, Promega, Madison, WI) in normoxia and hypoxia, as previously described (13). Hypoxic conditions were generated by either growing cells in a 37 °C incubator in a sealed chamber containing a mixture of gases with 1% oxygen or by culturing cells in 100 μm cobalt chloride (Sigma).

RNA Isolation and PCR Analysis

RNA was extracted from whole cell lysates and converted into cDNA using the AMV reverse-transcriptional system (Promega) in the presence of random hexamers (Invitrogen). The cDNA was used for conventional PCR or quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) with specific gene primers as follows: Semaphorin 4D (BC054500) forward: 5′-GTCTTCAAAGAAGGGCAACAGG-3′, reverse: 5′-GAGCATTTCAGTTCCGCTGTG-3′; and 18S forward: 5′-TTGACGGAAGGGCACCACCAG-3′, reverse: 5′-GCACCACCACCCACGGAATCG-3′. An MYIQ real-time PCR detection system and SYBR green PCR mix (Bio-Rad) were used to carry out the real-time PCR. The relative abundance of Sema4D transcript was quantified using the comparative Ct method with 18S as an internal control. All data were analyzed from three independent experiments and statistical significance validated by Student's t test.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

HN12 cells serum starved for 16 h were subjected to hypoxia for 24 h, cross-linked with 0.8% formaldehyde, and then briefly sonicated to fragment the chromatin. Lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and diluted in a ChIP dilution buffer (0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100, 2 mm EDTA, 167 mm NaCl, 16.7 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.1) containing protease inhibitors, precleared with salmon sperm DNA-coated protein A-agarose beads, and immunoprecipitated with 5 μg of anti-HIF-1α antibody or rabbit IgG (as the negative control) overnight at 4 °C. Antibody complexes were collected with protein A-agarose beads, washed in ChIP dilution buffer, and reverse cross-linked by incubation at 65 °C for 4 h. The samples were then treated with proteinase K for 2 h at 42 °C and the precipitated DNA amplified by PCR using the following primers: Sema4D HRE1,2 forward: 5′-TTATATAGGCTGGTGGGTGCG-3′; reverse: 5′-TGAAATCTGCAGGCTCCAGTC-3′; Sema4D HRE3 forward: 5′-ATTGAGCCGTCTCTGGAAGATC-3′; reverse: 5′-GCAGGTGGACAGTGTTGCTATG-3′; Sema4D HRE4 forward: 5′-CATAGCAACACTGTCCACCTGC-3′; reverse 5′-ACGGATGGAAGGGAATTACTT-3′. For a positive control, ChIP was performed on the VEGF promoter at a known site for HIF-1 binding, using the following primers: forward: 5′-ACAGACGTTCCTTAGTGCTGG-3′; reverse: 5′-AGCTGAGAACGGGAAGCTGTG-3′.

Migration Assays

Serum-free medium containing the indicated cell type or chemoattractant was placed in the bottom well of a Boyden chamber while serum-free EBM containing HUVEC was added to the top chamber. The assay was performed and quantified as previously described (14).

RNA Interference and Generation of Lentivirus

The short hairpin (sh) RNA sequences for human Sema4D and HIF-1β were acquired from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory's RNAi library (RNAi Codex). Oligonucleotides (Invitrogen) based on the following sequence worked best to knock down Sema4D and HIF-1β protein levels, respectively: 5′-GGCCTGAGGACCTTGCAGAAGA-3′; 5′-CCAGCCAATATACAACTGTAA-3′. The oligonucleotides generated were cloned into lentiviral expression vectors as previously described (6), as was HIF-1α mODD cDNA (the gift of Dr. Abraham Schneider). HIF-1α siRNA oligos were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and transfected into cells using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen).

In Vivo Tumorigenesis Assay

2 × 106 HN6 cells infected ex vivo with control lentiviruses, control virus and virus coding for HIF-1α mODD, or viruses coding for HIF-1α mODD and Sema4D shRNA, were resuspended in 250 μl of serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with an equal volume of Cultrex basement membrane extract (Trevigen, Rockville, MD) and injected subcutaneously into nude mice. After tumor growth had been recorded, animals were sacrificed, and tumors were removed, photographed, and processed for microscopy as described (11).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded tissues were deparaffinized, hydrated, rinsed with PBS, and processed as previously described (11). Primary antibodies were diluted in 2% BSA in PBS/0.1% Tween 20 and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The antibodies used were as follows: HIF-1α (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers MA; 1:50 dilution); Sema4D (BD Transduction Laboratories; 1:50 dilution). The slides were washed in PBS, incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody (1:400 dilution; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h, and treated with ABC complex (Vector Stain Elite; Vector Laboratories) for 30 min at room temperature. The slides were developed in 3,3-diaminobenzidine (FASTDAB tablets; Sigma), counterstained with dilute Mayer's hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. Images were taken with a SPOT digital camera attached to an Axiophot microscope (Zeiss).

Immunofluorescence

OCT-embedded frozen tissues were cut onto silanated glass slides, air-dried, and stored at −80 °C. Cryosections were thawed, hydrated, and washed in PBS. For Glut-1 and Sema4D co-immunofluorescence, sections were incubated in blocking solution (3% fetal bovine serum in 0.1% Triton X-100 PBS) for 1 h followed by incubation with the first primary antibody diluted 1:100 in blocking solution at 4 °C overnight. After washing, slides were sequentially incubated with the biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, 1:300) for 1 h, followed by the fluorophore-labeled avidin antibody (Vector Stain Elite, ABC kit, Vector Laboratories) for 30 min at room temperature. The slides were washed and incubated in avidin/biotin blocking kit (Vector Laboratories) before repeating the staining process with the second primary antibody. The following antibodies were used: Glut-1 (1:200 dilution in PBS with 3% fetal bovine serum; Abcam); Sema4D (BD Transduction Laboratories; 1:50 dilution). For CD31, anti-CD31 primary antibody was used (anti-PECAM; BD Pharmingen; 1:100 dilution) and tissues mounted in Vectashield mounting medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories).

Statistical Analysis

Student's paired t tests were performed on means, and p values calculated: *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001.

RESULTS

HIF-1α Is Elevated in HNSCC Cells and Strongly Induced in Hypoxia

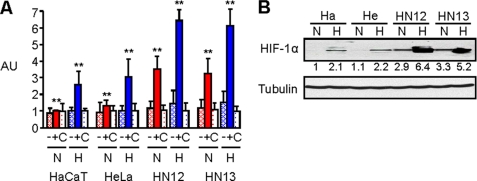

We and others have noted that the HNSCC cell lines HN12 and HN13 grow well as tumor xenografts in immunocompromised mice, while HeLa and HaCaT xenografts are not similarly tumorigenic. To characterize the hypoxic responses in HNSCC, we electroporated HN12 and 13 cells along with HaCaT and HeLa cells with control DNA, a luciferase reporter plasmid containing the wild-type VEGF promoter, which is known to be activated in hypoxia, or the plasmid containing a mutated VEGF promoter (13) and subjected the cells to a luciferase assay under normoxic and hypoxic conditions overnight. HNSCC cells expressing the wild-type construct exhibited an enhanced luciferase response under baseline normoxic conditions and an increase in fluorescence in hypoxia compared with HaCaT and HeLa controls (Fig. 1A). The results of this luciferase assay correlated well with the levels of HIF-1α protein observed in an immunoblot of lysates of these cells, which showed constitutively high levels of HIF-1α even under normoxic conditions in HNSCC cell lines, but not in HaCaT or HeLa cells, and a robust increase when the HNSCC cells were subjected to hypoxic conditions (Fig. 1B). Taken together, these results demonstrate that HNSCC cells have an enhanced hypoxic response compared with the epithelial cell lines HaCaT and HeLa.

FIGURE 1.

HNSCC cells exhibit high levels of HIF-1α protein and HIF-1 transcriptional activity. A, HaCaT, HeLa, HN12, and HN13 cells were electroporated with a luciferase reporter plasmid containing a mutated (−) or wild-type (+) VEGF promoter, or control DNA (C) and subjected to a luciferase assay measuring fluorescence (arbitrary units, AU, normalized with Renilla) following exposure to normal tissue culture conditions (normoxia- N) or an atmosphere of 1% oxygen overnight (hypoxia- H). Student's t tests were performed comparing HN12 and HN13 expressing the wild-type luciferase reporter in normoxia and hypoxia with HaCaT and HeLa under identical conditions, and p values calculated (**, p ≤ 0.01). B, immunoblot for HIF-1α (upper panel) in the indicated HNSCC cell lines, HaCaT (Ha) and HeLa (He) cells, in normoxia or hypoxia. Protein levels are quantified below the immunoblot as a fold-increase relative to HaCaT cells in normoxia. Tubulin is used as the loading control (lower panel).

Expression of Sema4D Protein and mRNA Are Elevated in HNSCC Cells and Strongly Induced in Hypoxia

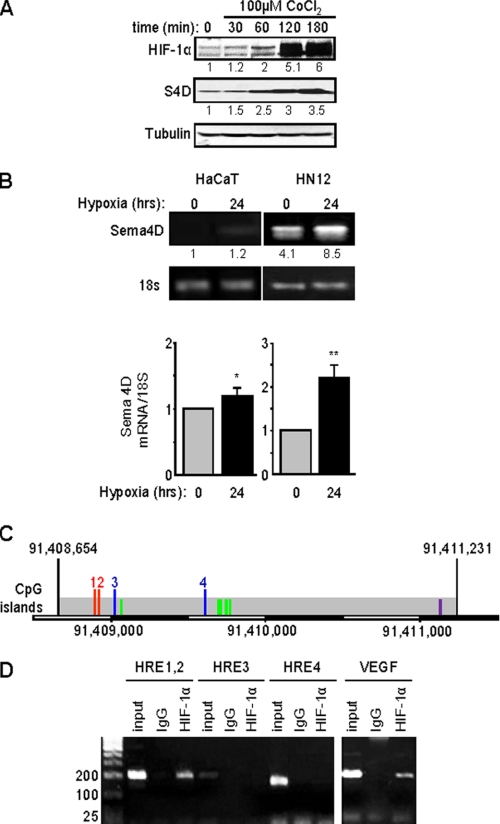

We noted that protein levels of Sema4D increased in HNSCC cells along with HIF-1α following treatment with CoCl2 (Fig. 2A), a chemical that mimics conditions of hypoxia by blocking VHL-mediated HIF-1α degradation. To see if this was a transcriptional effect, we looked at Sema4D mRNA levels in HNSCC when compared with the response in HaCaT cells, an immortalized but non-transformed epithelial cell line. Similar to the luciferase and immunoblot findings, the level of Sema4D message was significantly higher in HN12 cells in normoxia compared with HaCaT cells in both RT-PCR (Fig. 2B, upper panel) and quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) (Fig. 2B, lower panel). There was a greater than 2-fold increase in Sema4D mRNA levels in HN12 cells compared with only a slight elevation in HaCaT cells following exposure to hypoxic conditions for 24 h.

FIGURE 2.

Expression of Sema4D protein and mRNA are elevated in HNSCC cells and strongly induced in hypoxia. A, HN12 cells exhibit increasing levels of Sema4D (S4D, middle panel) when exposed to the hypoxia-mimetic CoCl2, a response correlated with increasing levels of HIF-1α (upper panel). Protein levels are quantified below each blot as a fold-increase relative to untreated cells. Tubulin is used as the loading control (lower panels). B, HaCaT cells (left panel) and HN12 (right panel) were cultured under normal conditions or hypoxia for 24 h, and total RNA was extracted to detect steady-state Sema4D transcripts in a quantitative conventional PCR analysis. Band intensities are quantified below each image as a fold-increase relative to untreated HaCaT cells. Housekeeping 18S mRNA was used as a control. The bar graph represents the ratio of Sema4D mRNA to 18S mRNA for real time PCR from three independent experiments. Student's t tests were performed for HaCaT and HN12 in hypoxia, compared with normoxia, and p values calculated (*, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01). C, potential Sema4D promoter region. Predicted TSS within a region of CpG islands are indicated by the green lines. The first two HRE present, which conform to the expanded sequence 5′-BRCGTGVBBB-3′ (where B is C, G, or T, R is G or A, and V is A, C, or G) are numbered 1 and 2 (red lines). Two other HRE, which contain the core sequence 5′-RCGTG-3′, are numbered 3 and 4 (blue lines). An AP-1 site conforming to the sequence 5′-TGASTCA-3′ (where S is G or C) is shown in purple. The scale bar at the bottom shows the nucleotide number on the reverse strand of chromosome 9. D, ChIP assay. Chromatin lysates from HN12 cells exposed to hypoxic conditions were immunoprecipitated with anti-HIF-1α antibodies. Purified, fragmented DNA was subjected to PCR with a set of primers to HRE 1 and 2 (done together due to their close proximity), HRE 3 and HRE 4, as indicated in C, or for the VEGF promoter as a positive control (right panel) followed by gel electrophoresis. HIF-1 binding to HRE 1 and 2 is observed in HN12 cells exposed to hypoxic conditions. Input represents the PCR products from purified DNA fragments alone. Rabbit IgG was used as the negative control for HIF-1α immunoprecipitation (IgG). Size markers are shown on the left.

To determine if Sema4D transcription is regulated by HIF-1α, we wanted to study the promoter. The gene for Sema4D is located at 9q22.2-q31, and corresponds to open reading frame 164 on the minus (reverse) strand, according to information acquired from the Ensembl data base, but the promoter and transcription start site (TSS) have yet to be characterized. Available through Ensembl is Eponine, a program that uses “a probabilistic method” to predict TSS in mammalian genomic sequences based upon recognition of several key elements, including areas of CpG enrichment flanking TATA box elements (15). Using Eponine, a CpG-rich island was identified upstream of Sema4D that conforms well to a predicted promoter region (Fig. 2C). This region contains five potential TSS and four HRE, two of which conform to the entire 10-bp sequence 5′-BRCGTGVBBB-3′ (where B is C, G, or T, R is G or A, and V is A, C, or G) (Fig. 2C, indicated by the red lines labeled 1 and 2) and two that exhibit the 5-bp core sequence 5′-RCGTG-3′ (Fig. 2C, blue lines 3 and 4) (16). Sema4D is likely regulated by numerous factors, and we also discovered one complete AP-1 site following the sequence 5′-TGASTCA-3′ (where S is G or C) (Fig. 2C, purple line). A search for other hypoxia and stress related transcription factor sites, such as NF-κB, p53, and Egr-1, yielded no results. We then investigated HIF-1α binding to this region by means of ChIP analysis. A band was observed in the immunoprecipitated fragments from the first two HRE in cells exposed to hypoxic conditions, as well as from the VEGF promoter, which was used as the positive control (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these results show that Sema4D expression is regulated by hypoxia in a response that is enhanced in HN12 cells and occurs at the level of transcription.

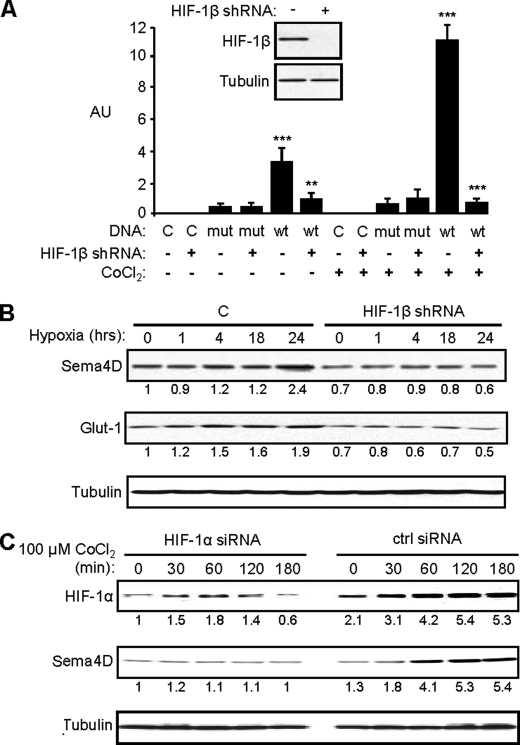

Induction of Sema4D Is Controlled by HIF-1

To further determine if elevated levels of Sema4D in normoxia and its induction in hypoxia in HNSCC is due to HIF-mediated activation of Sema4D transcription, we targeted HIF-1β, the binding partner for all forms of HIF (17), for knockdown. We generated HIF-1β short hairpin (sh) RNA oligonucleotides from sequences acquired from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory RNAi library (RNAi Codex) and confirmed that they worked by demonstrating that HNSCC cells infected with lentiviruses manufactured to express HIF-1β shRNA exhibited reduced levels of HIF-1β protein in an immunoblot (Fig. 3A, inset). Cells expressing empty vector or a luciferase reporter plasmid with a mutated VEGF promoter (as controls) or the wild-type VEGF promoter were control infected or infected with lentivirus expressing the functional HIF-1β shRNA construct and subjected to a luciferase assay. HIF-1β shRNA successfully eliminated HIF-1 activity in cells growing in cobalt chloride that were expressing the reporter plasmid with the wild-type VEGF promoter (Fig. 3A). When HN12 cells infected with lentivirus expressing HIF-1β shRNA or controls were exposed to hypoxic conditions (1% oxygen in a hypoxia chamber), we observed increases in protein levels of Glut-1, a known HIF-1 target (18), and Sema4D only in control infected cells and not in cells expressing HIF-1β shRNA (Fig. 3B). To rule out the contribution of other hypoxia-inducible transcription factors and their pathways, such as HIF-2α for example, we transfected HN12 cells with a control or HIF-1α siRNA oligos and treated with CoCl2. We observed an induction of HIF-1α and Sema4D protein levels in control cells growing in CoCl2 but an attenuation of this response and even a slight reduction in Sema4D levels in cells transfected with HIF-1α siRNA oligos (Fig. 3C). These results show that Sema4D protein levels are under the control of the HIF-1 transcriptional complex.

FIGURE 3.

Sema4D protein levels increase in hypoxia in a HIF-1-dependent manner. A, HN12 exhibit reduced levels of HIF-1β protein when infected with lentivirus coding for shRNA against HIF-1β (inset). Cells expressing control shRNA (HIF-1β shRNA: −) or HIF-1β shRNA (HIF-1β shRNA: +) and either control DNA (DNA: C) or luciferase reporter plasmids containing the wild-type (DNA: wt) or mutated (DNA: mut) VEGF promoter were subjected to growth conditions with (CoCl2: +) or without (CoCl2: −) cobalt chloride for 2 h. A luciferase assay was performed with fluorescence (arbitrary units, AU) normalized by Renilla. Fluorescence was seen in cells expressing the wild-type luciferase construct and control shRNA lentivirus growing in CoCl2 but this was abolished by functional HIF-1β shRNA. Student's t tests were performed comparing cells expressing control or functional HIF-1β shRNA and wild-type reporter in normoxia or hypoxia, as shown, and p values calculated (**, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001). B, HIF-1β shRNA lentivirus-infected HN12 cells and control cells (C) were subjected to hypoxia (1% oxygen) for the times indicated and immunoblotted for Sema4D (upper panel) and Glut-1 (middle panel). Sema4D and Glut-1 protein levels increase in control cells growing in hypoxia, but these responses were lost in cells infected with HIF-1β shRNA-expressing lentivirus. C, increases in HIF-1α and Sema4D (upper and middle panel, respectively) observed in CoCl2-treated HN12 cells are lost in cells expressing HIF-1α siRNA oligos (HIF-1α siRNA) compared with controls (ctrl siRNA). Protein levels are quantified below each blot as a fold-increase relative to untreated controls (A) or untreated shRNA-expressing cells (B). Tubulin is used as a loading control in all immunoblots (lower panels).

HIF-1 Stabilization Results in Up-regulation of Sema4D and Promotion of Endothelial Cell Chemotaxis in Vitro

To confirm that HIF-1α is responsible for Sema4D induction, we utilized the HIF-1α mODD construct (9). HIF-1α mODD is resistant to VHL-mediated ubiquitination and degradation because it lacks the prolyl residues that are targeted for hydroxylation by the PHD. When expressed in cells it results in a stable HIF-1 transcriptional complex even in normoxia. We expressed a plasmid coding for this mutant and a control plasmid in the epithelial cell lines HaCaT and HeLa, which normally demonstrate little to no detectable levels of Sema4D protein and do not exhibit a strong hypoxic response. As shown in Fig. 4A, when HIF-1α levels increased due to the effects of the degradation-resistant mutant (upper panel), these cells also began expressing high levels of Sema4D protein (middle panel). To establish the biological significance of this effect, we looked for the ability of the HaCaT cells to serve as chemoattractants for human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) in a Boyden chamber migration assay. As earlier, we observed an increase in Sema4D protein levels in cell lysates as a result of HIF-1α mODD expression, but we blocked this increase by infection with lentiviruses expressing the Sema4D shRNA construct (Fig. 4B). When used as chemoattractants in a migration assay, we found that cells expressing HIF-1α mODD could now attract endothelial cells. However, this effect was partly blocked by infection with Sema4D shRNA-expressing lentivirus (Fig. 4C). These results establish that HIF-1-mediated increases in Sema4D are important for endothelial cell chemotaxis.

FIGURE 4.

HIF-1 stabilization results in up-regulation of Sema4D and promotion of endothelial cell chemotaxis in vitro. A, HaCaT (Ha) and HeLa (He) cells transfected with EGFP or HIF-1α mODD were immunoblotted for Sema4D protein. Cells expressing high levels of HIF-1 under normoxic conditions (top panel, HIF-1α) exhibit high levels of Sema4D protein in cell lysates (middle panel). Tubulin was used as a loading control (lower panel). B, HaCaT cells expressing control DNA (HIF-1α mODD: −) or HIF-1α mODD (+) and infected with control lentivirus (Sema4D shRNA: −) or lentivirus coding for Sema4D shRNA (+) were immunoblotted for HIF-1α and Sema4D. Cells overexpressing HIF-1α (top panel), and hence exhibiting enhanced HIF-1 transcriptional activity, show high levels of Sema4D protein in cell lysates (middle panel). This response was abrogated in cells infected with Sema4D shRNA-expressing lentivirus. Tubulin was used as a loading control (lower panel). C, these cells were used as chemoattractants for endothelial cells in a Boyden chamber migration assay. Enhanced endothelial cell migration (as determined by pixel intensity of stained cells, PI, y-axis, bottom panel) is induced by HIF-1α mODD-expressing HaCaT (HIF-1α mODD), an effect reduced in cells infected with Sema4D shRNA-expressing lentivirus (S4D shRNA, HIF-1α mODD). Positive control (pos ctrl) represents migration toward 10% fetal bovine serum. Negative control (neg ctrl) is toward 0.1% BSA. Migration toward untransfected HeLa cells (untrans) is shown. Student's t tests were performed comparing HIF-1α mODD-expressing HaCaT with untransfected controls and those also expressing Sema4D shRNA, as shown, and p values calculated (**, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001). The migration assay membrane is shown (top panel).

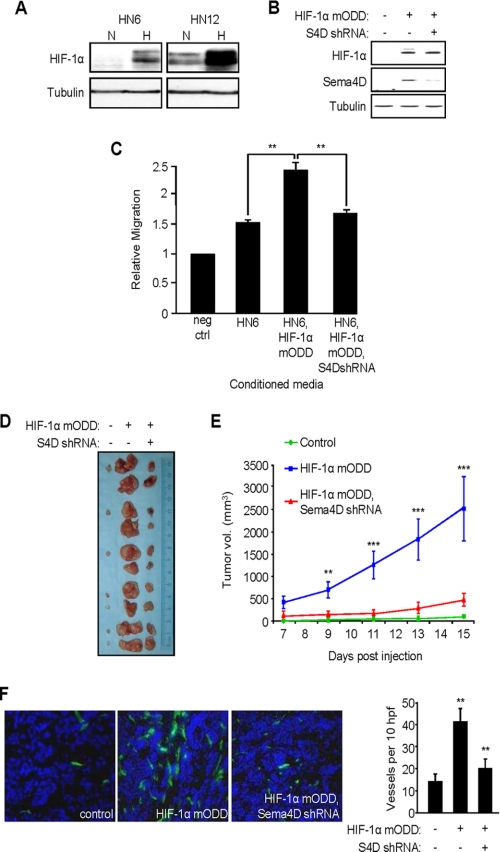

HIF-1-induced Up-regulation of Sema4D Is Responsible for Enhanced Tumor Growth and Vascularity in Vivo

HN6 cells express low levels of Sema4D when compared with other HNSCC lines (6) and grow slowly as xenografts in immunocompromised nude mice. Coincidentally, they also exhibit attenuated HIF-1α induction in hypoxia compared with HN12 cells (Fig. 5A). To determine whether HIF-1-induced up-regulation of Sema4D has biological significance on tumorigenicity in vivo, we engineered HIF-1α mODD and Sema4D shRNA lentiviral expression vectors for stable gene transfer into HN6 cells. The high infection efficiency of this system (19) enabled us to use mass cultures of infected cells, thus avoiding the need to isolate cell clones. While control infected HN6 cells exhibit low baseline levels of HIF-1α, and therefore an attenuated hypoxic response, infection with the HIF-1α mODD-expressing lentivirus induced increased HIF-1α and Sema4D protein levels (Fig. 5B). Co-infection with Sema4D shRNA-expressing lentivirus reduced the levels of Sema4D in these cells, as expected (Fig. 5B, middle panel). Serum-free medium conditioned by these cell populations were used as the chemoattractants for HUVEC cells in an in vitro migration assay. Compared with migration toward serum-free medium containing 0.1% BSA (negative control), medium conditioned by control virus-infected HN6 cells exhibited some chemotactic effects on endothelial cells, inducing migration by ∼50% probably as a result of production of any number of pro-chemotactic factors. Endothelial cell migration increased when these cells were expressing HIF-1α mODD, which would enhance expression and production of Sema4D as well as VEGF and other hypoxia-inducible products. However, when co-infected with lentivirus coding for Sema4D shRNA, migration was reduced to a level only slightly higher than controls (Fig. 5C), stressing the importance of the contribution of HIF-1α-induced production of soluble Sema4D by these tumor cells to the angiogenic response. When used as xenografts in nude mice, tumors composed of cells infected with HIF-1α mODD lentivirus grew much larger and more rapidly than tumors from control infected cells (many of which failed to grow at all), but growth was attenuated when the HN6 cells were co-infected with the lentivirus coding for Sema4D shRNA (Fig. 5D). The results of tumor volume measurements are shown graphically in Fig. 5E. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed enhanced vascularity in tumors composed of cells infected with HIF-1α mODD-expressing lentivirus when compared with control tumors or tumors co-infected with HIF-1α mODD and Sema4D shRNA, as demonstrated by anti-CD31 staining (Fig. 5F, left panels). These results, quantified in the bar graph (Fig. 5F, right panel), indicate that HIF-1-mediated up-regulation of Sema4D is important for enhanced tumor growth and vascularity.

FIGURE 5.

Sema4D knockdown reduces HIF-1α-induced tumor growth and vascularity. A, immunoblot shows greater levels of HIF-1α in normoxia and an increase in hypoxia in HN12 compared with HN6 (upper panel). Tubulin was used as a loading control (bottom panel). B, immunoblot analysis for HIF-1α (top panel) and Sema4D (middle panel) in HN6 cells co-infected with control lentiviruses (HIF-1α mODD: −; Sema4D shRNA: −), lentivirus coding for HIF-1α mODD (+) and control lentivirus (Sema4D shRNA: −), or lentivirus coding for Sema4D shRNA (+) and HIF-1α mODD (+). Tubulin was used as a loading control (bottom). C, medium conditioned by HN6 cell populations infected with control lentiviruses (HN6), HIF-1α mODD-expressing and control lentivirus (HN6, HIF-1α mODD), or Sema4D shRNA and HIF-1α mODD virus (HN6, HIF-1α mODD, S4D shRNA) were used as chemoattractants for HUVEC cells in an in vitro migration assay. Migration was scored relative to that seen in negative control wells (0.1% BSA, neg ctrl). Student's t tests were performed comparing migration seen in medium conditioned by HN6 expressing HIF-1α mODD with control HN6 and those co-expressing Sema4D shRNA, as shown, and p values calculated (**, p ≤ 0.01). D, representative tumors derived from HN6 cells infected with control lentiviruses or lentiviruses expressing the HIF-1α mODD construct with or without co-infection with virus expressing Sema4D shRNA, shown at the time of harvesting. E, quantification of tumor volume results from C from day 7–15 post-engraftment of the three populations of cells. Student's t tests were performed, post day 9, comparing growth of HIF-1α mODD-expressing tumors with those co-expressing Sema4D shRNA, as shown, and p values calculated (**, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001). F, CD31 stain of frozen sections of tumors derived from HNSCC cells infected with control lentiviruses (left panel), HIF-1α mODD-expressing lentivirus (middle panel), and HIF-1α mODD and Sema4D shRNA lentiviruses (HIF-1α mODD, S4D shRNA, right panel). Quantification of the number of vessels per 10 high-power fields in CD31-stained xenografts is shown in the bar graph (right). Student's t tests were performed, comparing the number of blood vessels from tumors expressing HIF-1α mODD to numbers seen in those co-expressing Sema4D shRNA, and p values calculated (**, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001).

Sema4D and HIF-1 Are Up-regulated in HNSCC and Expressed in the Same Areas of Tumor

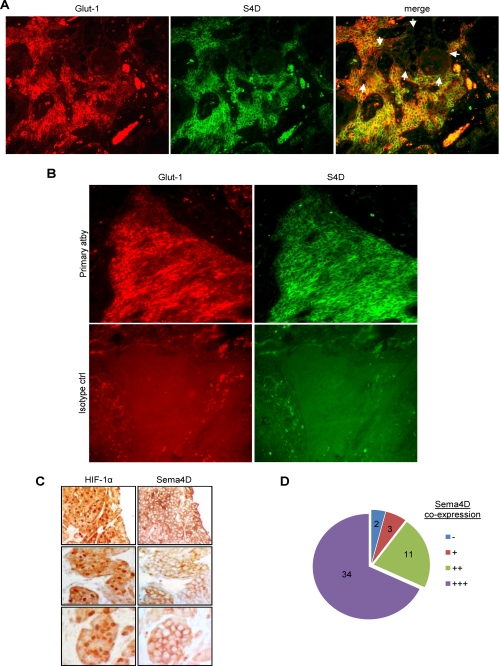

If Sema4D is an HIF-1α-inducible gene product, it follows that its expression should occur in the same cells and regions of tumor where HIF-1α is stabilized and where HIF-1 transcriptional activity is elevated. We looked for this phenomenon in vivo by performing co-immunofluorescence in HNSCC tumor samples. We co-stained for Glut-1 in order to identify areas of hypoxia (18). We observed Glut-1 expression, and hence stable HIF-1α and HIF transcriptional complex activity, scattered throughout the tumor (Fig. 6A, left panel, in red). As expected, we also observed expression of Sema4D (Fig. 6A, middle panel, in green). The distribution of both proteins correlated well, both in their presence (Fig. 6A, right panel, merged image in yellow) and absence (right panel, unstained area indicated by white arrows). Isotype-matched control stains were performed and showed that nonspecific staining was not present (Fig. 6B). Next, we performed immunohistochemistry for HIF-1α directly, followed by an analysis of Sema4D in serial sections. We observed a correlation between HIF-1 in the nucleus (Fig. 6C, left column) and expression of Sema4D at the cell surface (Fig. 6C, right column). Using this method, we examined large clusters and areas of abundant HIF-1α expression, such as those indicated in Fig. 6C, in 50 high power fields (hpf) among 5 different HNSCC for co-expression of Sema4D and found a strong correlation (Fig. 6D). These results demonstrate that Sema4D expression occurs in areas of HIF-1 activity in tumors.

FIGURE 6.

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry for Glut-1, Sema4D, and HIF-1α in HNSCC. A, Glut-1 expression (Glut-1, red, left column) and Sema4D expression (S4D, green, middle panel) occur in the same cells and in the same areas of tumor (merge, in yellow, right panel). In areas lacking Glut-1 expression, Sema4D is also not expressed (merge, right panel, indicated by white arrows). B, co-immunofluorescence in HNSCC biopsy specimens for Glut-1 (left) and Sema4D (right). Fluorescence in samples processed with the primary antibodies (top row) indicates specificity when compared with isotype control antibodies (bottom row). C, immunohistochemistry in serial sections of HNSCC biopsy specimens for HIF-1α (left column) and Sema4D (right column) demonstrate expression in the same cells and in the same areas of tumor. D, 50 hpf from 5 HNSCC exhibiting expression of nuclear HIF-1α in immunohistochemistry were examined in serial sections for co-expression of Sema4D. 34 cases demonstrated very strong Sema4D co-expression (+++) and 11 showed strong expression (++). 3 areas weakly expressed Sema4D (+) while 2 areas showing HIF-1α had little to no corresponding Sema4D (−).

DISCUSSION

A primary effector for adaptation to hypoxia in mammalian cells is the HIF family of transcription regulators. These proteins activate the expression of a broad range of genes that alter cell physiology in conditions of low oxygen concentration for the purpose of promoting survival. This response, essential for normal development, is usurped by tumor cells to stimulate neo-vascularization to meet the metabolic demands of a growing tumor. Recent studies suggest that activation of the HIFs is a common consequence of a wide variety of mutations underlying human cancer (9). Indeed, the HNSCC cell lines we studied here exhibited high levels of HIF-1α protein, even at baseline, and an enhanced activation of a hypoxia response in immunoblots and luciferase assays.

There are striking similarities between the process of blood vessel branching and nerve growth during development (5). It is now known that proteins involved in transmitting axonal guidance cues, such as the plexins and semaphorins, can also play a critical role in the regulation of blood vessel growth and development. Sema4D has been shown not only to promote angiogenesis, but also to enhance invasive growth in malignancies (20) and protect cancer cells against apoptosis (21). Recent work has revealed a correlation between high levels of Sema4D expression in some sarcomas and a higher mitotic count, cellularity, Ki-67 labeling index and poorer overall patient prognosis (22). Data suggest that like other pro-angiogenic factors, plexins and semaphorins are influenced by changes in oxygen tension (7). Therefore, we attempted to look for a link between hypoxia and Sema4D expression in HNSCC.

We noted increases in Sema4D protein and message in hypoxia. Using available databases and ChIP analysis, we identified potential TSS and the presence of HRE upstream of the Sema4D gene that exhibited HIF-1 binding, though a more thorough promoter analysis using other techniques such as RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) and an informatics approach will be required in the future. We demonstrated that the observed increases in Sema4D levels in hypoxia were dependent upon HIF-1 and were biologically significant, as expression of the HIF-1α mODD degradation-resistant mutant lead to overexpression of Sema4D even in cells that normally express very little protein, and an enhanced ability of cells to act as chemoattractants for endothelial cells in a migration assay. When Sema4D levels were reduced with shRNA-expressing lentiviruses, this pro-angiogenic phenotype was greatly attenuated, though it should be noted not totally blocked. This could be due to functional redundancy for Sema4D/Plexin-B1-mediated angiogenesis, which has been observed in a knock-out study (23), and the fact that HIF-1α-overexpressing cells still produce other proteins that are components of the hypoxia response and could promote angiogenesis, such as VEGF.

HN6 cells do not express high levels of HIF-1α or Sema4D, induce only a slight pro-angiogenic response in HUVEC cells in vitro, and do not grow well as subcutaneous xenografts in nude mice in vivo. However, we could induce a more pro-angiogenic phenotype in HN6 cells by overexpressing the HIF-1α mODD degradation-resistant mutant. We show that hypoxia-driven expression of Sema4D is important in endothelial cell chemotaxis and tumor development, as this phenotype was attenuated by introduction of Sema4D shRNA. Once again, these responses were not totally eliminated. HN6 cells expressing both HIF-1α mODD and Sema4D shRNA exhibited an ‘intermediate’ phenotype for induction of HUVEC migration, probably due to the continued production of VEGF and other pro-angiogenic, pro-survival factors that are part of the HIF-1-mediated hypoxia response.

Production of soluble Sema4D from the surface of HNSCC cells, which we have previously shown to be induced by cell surface proteases (24), is likely not hindered by hypoxic growth conditions, since we observed HUVEC migration toward medium conditioned by HN6 cells and other cell types expressing HIF-1α mODD. In fact, we believe soluble Sema4D production may actually be enhanced since many proteases are themselves often induced by hypoxia (24), though such a conclusion will warrant further studies. Finally, immunofluorescence for Glut-1 and Sema4D in HNSCC tumor biopsy specimens demonstrated a strong correlation for these proteins. Immunohistochemical analysis of areas of HNSCC showing nuclear HIF-1α, and hence active HIF-1 transcriptional activity, revealed a correlation with cell surface expression of Sema4D.

We have previously demonstrated that Sema4D is a critical endothelial chemoattractant under normoxic conditions. Here we show that Sema4D is elevated in hypoxia and influences tumor growth and vascularity. These results show that the class IV semaphorins may be part of the hypoxia adaptive response, which is dysregulated in transformed cells and thus could present a new target for anti-angiogenic therapy in the treatment of oral cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Abraham Schneider for the generous gift of the HIF-1 α siRNA oligos and the HIF-1α mODD construct. We would also like to thank Dr. Silvia Montaner, Dr. Daniel Martin, Dr. J. Silvio Gutkind, Lynn Cross, and Angela Massey for technical assistance and encouragement.

Footnotes

- Sema4D

- semaphorin 4D

- HIF-1

- hypoxia-inducible factor-1

- mODD

- oxygen-dependent degradation domain mutant

- PHD

- prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins

- VHL

- von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- HNSCC

- head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HRE

- hypoxia response element

- VEGF

- vascular endothelial growth factor

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bismuth G., Boumsell L. (2002) Sci STKE 2002, RE4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torres-Vázquez J., Gitler A. D., Fraser S. D., Berk J. D., Van N. Pham, Fishman M. C., Childs S., Epstein J. A., Weinstein B. M. (2004) Dev. Cell 7, 117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van de Woude G. F., Jeffers M., Cortner J., Alvord G., Tsarfaty I., Esau J. (1997) CIBA Found. Symp. 212, 119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(1999) Cell 97, 551–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmeliet P., Tessier-Lavigne M. (2005) Nature 436, 193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basile J. R., Castilho R. M., Williams V. P., Gutkind J. S. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 9017–9022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siebold C., Berrow N., Walter T. S., Harlos K., Owens R. J., Stuart D. I., Terman J. R., Kolodkin A. L., Pasterkamp R. J., Jones E. Y. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 16836–16841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang G. L., Semenza G. L. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 1230–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanimoto K., Makino Y., Pereira T., Poellinger L. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 4298–4309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vajkoczy P., Farhadi M., Gaumann A., Heidenreich R., Erber R., Wunder A., Tonn J. C., Menger M. D., Breier G. (2002) J. Clin. Invest. 109, 777–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amornphimoltham P., Sriuranpong V., Patel V., Benavides F., Conti C. J., Sauk J., Sausville E. A., Molinolo A. A., Gutkind J. S. (2004) Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 4029–4037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basile J. R., Afkhami T., Gutkind J. S. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 6889–6898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forsythe J. A., Jiang B. H., Iyer N. V., Agani F., Leung S. W., Koos R. D., Semenza G. L. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 4604–4613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basile J. R., Barac A., Zhu T., Guan K. L., Gutkind J. S. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 5212–5224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Down T. A., Hubbard T. J. (2002) Genome Res. 12, 458–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirota K., Semenza G. L. (2006) Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 59, 15–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ke Q., Costa M. (2006) Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1469–1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iyer N. V., Kotch L. E., Agani F., Leung S. W., Laughner E., Wenger R. H., Gassmann M., Gearhart J. D., Lawler A. M., Yu A. Y., Semenza G. L. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 149–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laptenko O., Prives C. (2006) Cell Death Differ. 13, 951–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreuter M., Bielenberg D., Hida Y., Hida K., Klagsbrun M. (2002) Ann. Hematol. 81, Suppl. 2, S74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Granziero L., Circosta P., Scielzo C., Frisaldi E., Stella S., Geuna M., Giordano S., Ghia P., Caligaris-Cappio F. (2003) Blood 101, 1962–1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ch'ng E., Tomita Y., Zhang B., He J., Hoshida Y., Qiu Y., Morii E., Nakamichi I., Hamada K., Ueda T., Aozasa K. (2007) Cancer 110, 164–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fazzari P., Penachioni J., Gianola S., Rossi F., Eickholt B. J., Maina F., Alexopoulou L., Sottile A., Comoglio P. M., Flavell R. A., Tamagnone L. (2007) BMC Dev. Biol. 7, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basile J. R., Holmbeck K., Bugge T. H., Gutkind J. S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 6899–6905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]