Abstract

Insulin binds with high affinity to the insulin receptor (IR) and with low affinity to the type 1 insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor (IGFR). Such cross-binding, which reflects homologies within the insulin-IGF signaling system, is of clinical interest in relation to the association between hyperinsulinemia and colorectal cancer. Here, we employ nonstandard mutagenesis to design an insulin analog with enhanced affinity for the IR but reduced affinity for the IGFR. Unnatural amino acids were introduced by chemical synthesis at the N- and C-capping positions of a recognition α-helix (residues A1 and A8). These sites adjoin the hormone-receptor interface as indicated by photocross-linking studies. Specificity is enhanced more than 3-fold on the following: (i) substitution of GlyA1 by d-Ala or d-Leu, and (ii) substitution of ThrA8 by diaminobutyric acid (Dab). The crystal structure of [d-AlaA1,DabA8]insulin, as determined within a T6 zinc hexamer to a resolution of 1.35 Å, is essentially identical to that of human insulin. The nonstandard side chains project into solvent at the edge of a conserved receptor-binding surface shared by insulin and IGF-I. Our results demonstrate that modifications at this edge discriminate between IR and IGFR. Because hyperinsulinemia is typically characterized by a 3-fold increase in integrated postprandial insulin concentrations, we envisage that such insulin analogs may facilitate studies of the initiation and progression of cancer in animal models. Future development of clinical analogs lacking significant IGFR cross-binding may enhance the safety of insulin replacement therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus at increased risk of colorectal cancer.

Introduction

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated an association between the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM)4 with enhanced risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) (1–3). Animal models suggest that this risk is due to hyperinsulinemia (4, 5). An increased risk of CRC is conferred by treated-derived hyperinsulinemia, either as a direct consequence of insulin replacement therapy or as an indirect response to sulfonylurea secretagogues (6–9). A reduced CRC risk is by contrast associated with metformin treatment, which results in lower circulating insulin concentrations (7). Because of the global epidemic of type 2 DM (10, 11), it would be of interest to develop a form of insulin therapy that does not elevate CRC risk in this clinical setting.

A variety of evidence suggests that the association between hyperinsulinemia and CRC is due to aberrant activation of the type 1 IGF receptor (IGFR) (for review see Refs. 5, 12). Although underlying molecular mechanisms are incompletely understood, two models have been proposed (5, 12). The first posits cross-binding of insulin to IGFR in colonic epithelia and neoplastic clones, driving proliferation and tumorigenesis; the second proposes indirect IGFR activation through perturbation of the IGF-I axis (including expression of the IGF-binding proteins) (13, 14). Whereas consistent changes in bioactive IGF-I have been difficult to document (4), evidence favoring the direct model is provided by studies of epithelial proliferation in rats (15). Exogenous administration of insulin with a euglycemic clamp causes an acute dose-dependent increase in the proliferation rate of colonic epithelia despite decreased IGF-I expression. Such increased proliferation was not observed as a consequence of hyperglycemia or following infusion of a triglyceride emulsion (15).

Insulin binds with high affinity (Kd ∼0.05 nm) to the insulin receptor (IR) and with low but significant affinity (Kd′ ∼9.0 nm) to IGFR (16). Such cross-binding reflects the structural homology between insulin and IGF-I (17) and between IR and IGFR (18). The structural basis for receptor discrimination by insulin and IGF-I has been described recently (19). As a first step toward dissecting the molecular mechanism of insulin-dependent proliferation of colonic epithelia cells and their neoplastic transformation, we have therefore sought to design an insulin analog with more stringent receptor binding selectivity, i.e. increased binding to IR but decreased binding to IGFR. Because hyperinsulinemia in humans is typically characterized by a 3-fold increase in integrated serum insulin levels following a meal or oral glucose challenge (20), we sought to augment selectivity (Kd/Kd′) by at least this factor.

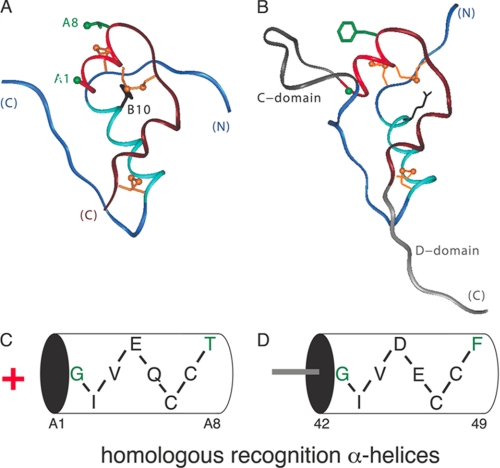

Our approach focuses on a conserved α-helix shared by insulin and IGF-I (residues A1–A8; bright red in Fig. 1, A and B). Mutagenesis of insulin and IGF-I suggests that in each case this α-helix makes a key contribution to respective receptor recognition (21, 22). The sequences of the A1–A8 α-helices are homologous (Fig. 1, C and D) with amino acid identities at five of eight positions (A1–A3, A6, and A7) and similarities at two positions (A4 and A5). The cognate importance of these homologous elements is highlighted by the observation of corresponding clinical mutations (ValA3 → Leu in insulin and ValA3 → Met in IGF-I) associated with DM (23) and growth retardation (24). We chose to focus on two solvent-exposed sites of salient difference between these α-helices, A8 and A1. ThrA8 (insulin) and PheA8 (IGF-I) differ in size, shape, and polarity as emphasized in the studies of De Meyts and co-workers (19). Although GlyA1 is conserved within the insulin-related family, we reasoned that its difference in charge, i.e. the distinction between an N-terminal amino group of the two-chain hormone versus the neutral peptide linkage of the single-chain grown factor, might indicate a difference in respective receptor environments. Photocross-linking studies employing para-azido-Phe substitutions (25) suggest that these sites are near the hormone-binding surface (26, 27) and so might enable modulation of receptor selectivity.

FIGURE 1.

Structure of insulin and IGF-I. A, ribbon model of insulin (T-state protomer; PDB code 4INS). The A-chain is shown in red (residues A1–A8) or maroon (A9-A21); the B-chain is shown in light blue (B1–B8) and dark blue (B9–B30). The A1 Cα and A8 side chain are shown in green; cystines are shown in gold (top to bottom: A7–B7, A6–A11, and A20–B19). B, ribbon model of IGF-I (PDB code 2DTG). The C and D domains of IGF-I are shown in dark and light gray. C and D, cylinder representations of A1–A8 α-helices in insulin (C) and IGF (D) with amino acid sequences inset. Plus sign (red) to left of cylinder in C indicates positive charge of its free α-amino group, not present in the single-chain IGF-I. Positions A1 and A8 (residues 42 and 49 in IGF-I) are highlighted in green. Residue numbers below cylinder in D pertain to full-length IGF-I.

Our design is based on the introduction of unnatural amino acids at A8 and A1 by chemical synthesis (28). Our study has three parts. Receptor binding studies of [d-A1,A8] analogs are first described, documenting enhanced selectivity. Photocross-linking studies of d-PapA1 are then presented to demonstrate the proximity of a d-side chain at A1 to the receptor interface. Finally, the crystal structure of a representative analog ([d-AlaA1,DabA8]insulin) is determined. The structure, determined at a resolution of 1.35 Å, defines the environment of the nonstandard side chain and excludes transmitted changes in adjoining receptor-binding surfaces. We envisage that insulin analogs of enhanced receptor selectivity (in addition to their biochemical and structural interest) will provide valuable reagents in animal studies of carcinogenesis (4). Pending advances in the manufacture of nonstandard proteins (29, 30) may enable corresponding clinical studies of the mechanistic relationship between insulin replacement therapy and CRC in type 2 DM (6–9).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of Insulin Analogs

The insulin B-chain was obtained by oxidative sulfitolysis of human insulin (kindly provided by Lilly). Modified A-chains were obtained by solid-phase peptide synthesis and combined with the wild-type B-chain as described previously (31). Purities were in each case >98% as evaluated by analytical reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry revealed no anomalous molecular masses. Insulin derivatives containing para-azido-Phe (Pap) were prepared as described previously (32).

CD Spectroscopy

CD spectra were obtained using an Aviv spectropolarimeter (33). Samples were dissolved in 50 mm potassium phosphate (pH 7.4) and diluted to 5 μm for denaturation studies. Guanidine denaturation data were fitted by nonlinear least squares to a two-state model as described previously (34).

Receptor Binding Assays

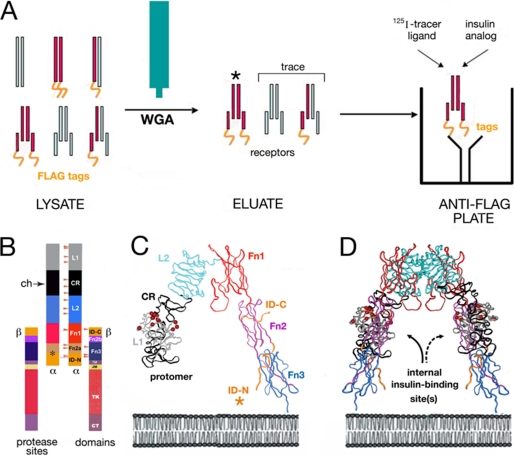

Binding assays employ a FLAG epitope-tagged holoreceptor (either IR isoform B or IGFR) transiently expressed in human 293 PEAK cells (CRL-2828, American Tissue Culture Collection) (35, 36). The receptors were partially purified by wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) chromatography and further fractionated on binding to polystyrene 96-well plates (Nunc Maxisorb) coated with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (FLAG M2 immunoglobulin G; Sigma). The plates were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the immunoglobulin (100 μl/well of 40 μg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline). This protocol (illustrated in schematic form in Fig. 2A) circumvents the confounding binding of insulin or insulin analogs to endogenous IGFR; 293 PEAK cells do not express detectable endogenous IR. Additional experimental details are provided as supplemental material. Relative activity is defined as the ratio of specific dissociation constants as determined by competitive displacement of bound 125I-TyrA14 human insulin (in the case of IR) or 125I-Tyr31 human IGF-I (in the case of IGFR). In all assays, the percentage of tracer bound in the absence of competing ligand was <15% to avoid ligand-depletion artifacts (35). Application to IGF-I analogs has been described previously (36). Binding data were analyzed by a two-site sequential model. Analysis by nonlinear regression enables determination of the high affinity ligand-receptor dissociation constant (35, 36). Control studies using untransfected PEAK cell lysates demonstrated that this microtiter plate antibody assay has negligible endogenous background. The biological potency of a representative insulin analog in regulating glucose disposal in vivo was corroborated in Lewis rats rendered diabetic by streptozotocin as described in the supplemental material.

FIGURE 2.

Design of biochemical assays. A, receptor binding studies employ an epitope-tagged receptor (IGFR or isoform B of IR). Left, cellular lysate contains a heterogeneous mixture of diverse proteins, including unprocessed dimeric receptor precursors (top row), overexpressed FLAG-tagged transfected receptor (red and gold), trace endogenous IGFR (light blue), and trace hybrid receptors. No endogenous IR is detectable in this system. Middle, WGA (teal) affinity chromatography excludes majority of contaminating proteins, including unprocessed receptor precursors. Asterisk indicates predominant component. Right, use of antibody-coated anti-FLAG plates enables specific capture of FLAG-tagged IR and IGFR. Trace hemi-tagged IR-IGFR hybrid receptors do not binding IR binding assay; likewise, trace hemi-tagged IGFR-IGFR receptors do not confound IGFR binding assay. B–D, photocross-linking studies exploit structure of IR ectodomain. B, domain organization of IR as (αβ)2 dimer. Color-coded segments indicate structural domains; at left are shown selected sites of limited proteolysis of photocross-linked complexes by chymotrypsin within the CR (ch, arrow) and at Fn2a/ID-N junction (asterisk). Beige arrowheads indicate sites of N-linked glycosylation in the extracellular portion of IR. Dashed lines outline domains (light gray) not present in the crystal structure of the IR ectodomain; these span the transmembrane α-helix (TM), juxtamembrane segment (JM), tyrosine kinase (TK), and C-terminal tail of β-subunit (βCT). C, ribbon model of component protomer of IR ectodomain (PDB code 2DTG). Individual domains L1, CR, L2, Fn1, Fn2, and Fn3 are shown in gray, black, light blue, red, purple, and dark blue, respectively. The insert domain (ID; asterisk) exhibits missing or discontinuous electron density (residues 655–755; IR isoform A); only respective N- and C-terminal subsegments of ID-N and ID-C are well defined (orange). Color code is in accord with B. D, inverted-V-shaped dimer. The position of the plasma membrane is indicated at bottom in schematic lipid bilayer.

Photocross-linking

Photoreactive insulin derivatives containing an N-terminal biotin tag at position A1 or B1 were prepared as described previously (37). Purified IR ectodomain (kindly provided by the late C. Yip) was incubated overnight with either 125I-labeled or biotinylated photoactive insulin derivatives at a hormone concentration of 100–200 nm at 4 °C with gentle shaking. Solutions were in each case transferred to a Costar assay plate (Corning Glass) for UV irradiation (20 s at 254 nm) using a Mineralight Lamp (model UVG-54, UVP, Upland, CA); the distance from the source was 1 cm. For analysis of ectodomain photoproducts after UV irradiation, covalent complexes were reduced with 2% β-mercaptoethanol or 100 mm dithiothreitol and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Photoproducts were identified using an avidin-based reagent (neutravidin, Pierce) or an antiserum specific for the N-terminal segment of the receptor α-subunit (IRα-N).

Mapping of Hormone-Receptor Photoproduct

Mapping of the hormone-receptor photoproducts was based on the modular IR domain organization (Fig. 2B) and the crystal structure of the ectodomain (Fig. 2, C and D). Mapping of photocomplexes to domains of the receptor α-subunit exploited limited chymotryptic digestion as described previously (37); key sites are located within the cysteine-rich domain (Fig. 2B, arrow) and at the junction between the second fibronectin homology domain (Fn2a) and the insert domain (Fig. 2B, asterisk). A 15-residue peptide within the latter segment (residues 714–718) was shown by Steiner and co-workers to photocross-link to a Pap probe at B25 (25). Methods of receptor purification, photocross-linking, and mapping are described in detail as supplemental material. In brief, WGA-purified receptors were cross-linked with photoactive insulins and digested at 37 °C with 100 μg/ml chymotrypsin (Sigma) in a solution of 50 mm HEPES at pH 7.4 containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.11 m NaCl. Digestions were stopped at successive times by heating aliquots at 95 °C for 5 min. An equal volume of Laemmli sample buffer was added, and the mixtures were treated with 100 mm dithiothreitol. Digestion mixtures were analyzed by 10–20% gradient gel (SDS-PAGE), blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with neutravidin or IRα-N as above. Proteolytic mapping permitted specific cross-linking efficiency of the PapB25 control analog to be estimated based on observation of an SDS-PAGE mobility shift between native proteolytic fragments of the α-subunit and their corresponding A- or B-chain adducts. The ratio of shifted-to-unshifted bands was 20–30% (data not shown), indicating that the efficiency of photocross-linking is at least this high. Efficiencies might be higher if the WGA-purified IR was not completely active, because inactive receptors would only contribute to the unshifted bands.

X-ray Crystallography

Crystals were grown by hanging-drop vapor diffusion in the presence of a 1:2.5 ratio of Zn2+ to protein monomer and a 3.7:1 ratio of phenol to protein monomer in Tris-HCl buffer as described. Drops consisted of 1 μl of protein solution (10 mg/ml in 0.02 m HCl) mixed with 1 μl of reservoir solution (0.02 m Tris-HCl, 0.05 m sodium citrate, 5% acetone, 0.03% phenol, and 0.01% zinc acetate at pH 8.0). Each drop was suspended over 1 ml of reservoir solution. Crystals (space group R3) were obtained at room temperature after 2 weeks. Data were collected from single crystals mounted in a rayon loop and flash-frozen to 100 K. Reflections from 40.92 to 1.35 Å were measured on CCD detector system on synchrotron radiation in Chess, Cornell University. Data were processed with programs DENZO (version 1.9.6) and SCALEPACK (version 1.9.6). The crystal belongs to space group R3 with unit cell parameters as follows: a = b = 81.84 Å, c = 33.52 Å, α = β = 90°, γ = 120°. The structure was determined by molecular replacement using CNS. Accordingly, a model was obtained using the native T2 dimer (Protein Data B code 4INS following removal of all water molecules, zinc, and chloride ions). A translation-function search was performed using coordinates from the best solution for the rotation function following analysis of data between 15.0 and 4.0 Å resolutions. Rigid-body refinement using CNS, employing overall anisotropic temperature factors and bulk-solvent correction, yielded values of 0.31 and 0.30 for R and Rfree, respectively, for data between 19.2 and 3.0 Å resolution. Between refinement cycles, 2Fo − Fc and Fo − Fc maps were calculated using data to 3.0 Å resolution; zinc and chloride ions and phenol molecules were built into the structure using the program O (38). The geometry was continually monitored with PROCHECK (39); zinc ions and water molecules were built into the difference map as the refinement proceeded. Calculation of omit maps (especially in the first eight residues of the B-chain N terminus of each monomer) and further refinement were carried out using CNS (40), which implement maximum likelihood torsion angle dynamics and conjugate gradient refinement. Data collection and refinement statistics are provided in Table 2. Additional structural analysis is described in the supplement material.

TABLE 2.

Data collection and structure refinement statistics

| Crystal parameter | |

| Space group | R3 |

| Unit cell parameters | a = b = 81.84, c = 33.52 Å |

| Data collection | |

| Resolution range | 40.92 to 1.35 Å |

| Reflections (total/unique) | 101,242/18,052 |

| Completenessa | 98.1% (93.0%) |

| Rmergea,b | 0.039 (0.141) |

| Iδ(I)a | 20.2 (5.1) |

| Structure refinement | |

| No. of monomers per asymmetric unit | 2 |

| Rcrystc | 0.198 |

| Rfreed | 0.228 |

| Root-mean-square deviation, bond lengths | 0.006 Å |

| Root-mean-square deviation, bond angles | 1.2° |

| No. of protein atoms | 820 |

| No. of solvent atoms | 122 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) (all atom) | 17.9 |

a Values in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

b Rmerge = ΣΣ|I(h)I − 〈I(h)〉|/ΣΣ I(h)I, where I(h)I is the observed intensity of the ith source, and 〈I(h)〉 is the mean intensity of reflection h over all measurements of I(h).

c Rcryst= Σ‖Fobs| − |Fcalc‖/Σ|Fobs|, where |Fobs| and |Fcalc| are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitude, respectively.

d Rfreeis calculated based on 10% of total reflections that were omitted in refinement.

Molecular Modeling

Solvent-accessible areas were obtained by using X-PLOR, and molecular cavities were calculated by using SURFNET (41). Rigid-body models of d-PapA1-insulin were built using InsightII (Accelrys Inc., San Diego) based on the structure of a T-state crystallographic protomer (2-Zn molecule 1; Protein Data Bank code 4INS).

RESULTS

Receptor Binding Studies

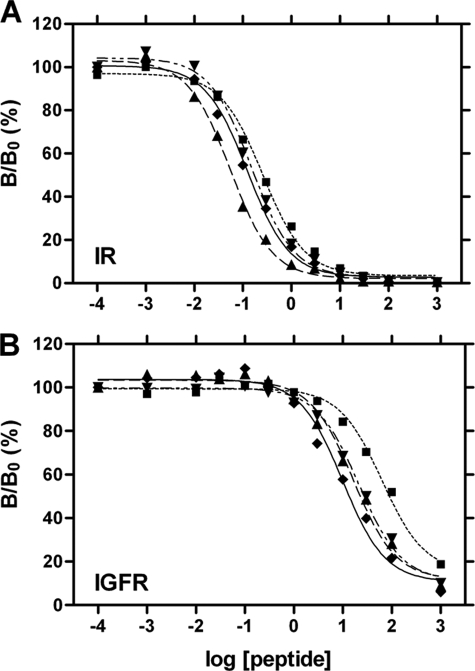

Design of an insulin analog with enhanced selectivity began with characterization of an analog in which ThrA8 was substituted by diaminobutyric acid (Dab), a side chain similar in size to Thr. Although positive charges are well tolerated at this site in insulin (42, 43), IGF-I contains PheA8 (by contrast a large aromatic side chain); this position has recently been shown to contribute to specificity (19). Accordingly, we predicted that DabA8-insulin would exhibit native IR binding but decreased IGFR binding. Receptor binding studies indeed demonstrated that the analog has near-native affinity for IR (91 ± 7% relative to wild-type insulin; Fig. 3A and column 2 in Table 1) but ∼2-fold decreased affinity for IGFR (Fig. 3B and column 3 in Table 1). We thus employed DabA8-insulin as a platform for additional modifications.

FIGURE 3.

Receptor binding studies. A, binding of insulin analogs to the IR (isoform B). B, cross-binding of insulin analogs to IGFR. Data represent competitive displacement of 125I-labeled insulin (A) or IGF-I (B). Symbol code in each panel is as follows: ♦, wild-type insulin; ▾, DabA8-insulin; ■, [d-AlaA1,DabA8]insulin; ▴, [d-LeuA1,DabA8]insulin; for clarity, data points of [d-AspA1,DabA8]insulin are not shown.

TABLE 1.

Receptor binding properties of insulin analogs

Under assay conditions, the dissociation constants (Kd and Kd′) for binding of wild-type insulin to IR and IGFR are 0.080 ± 0.01 and 5.7 ± 0.8 nm, respectively. Errors represent means ± S.E.

| Analog | Relative affinitiesa |

Receptor selectivity |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR | IGFR | Absolute | Relative | |

| Human insulin | 100 | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 333 ± 36 | 1 |

| Human IGF-I | NDb | 100 | ND | ND |

| DabA8-insulin | 91 ± 7 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 700 ± 105 | 2.1 ± 0.5 |

| [d-AlaA1,DabA8]Insulin | 48 ± 4 | 0.040 ± 0.002 | 1200 ± 160 | 3.6 ± 0.9 |

| [d-LeuA1,DabA8]Insulin | 275 ± 2 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 1375 ± 150 | 4.1 ± 0.8 |

| [d-AspA1,DabA8]Insulin | 53 ± 4 | 0.050 ± 0.03 | 1060 ± 150 | 3.2 ± 0.8 |

a The relative affinity of wild-type insulin for IR (column 2) is defined at 100%; the relative affinity of IGF-I for IGFR (column 3) is also defined as 100% but represents a different absolute dissociation constant.

b ND means not determined.

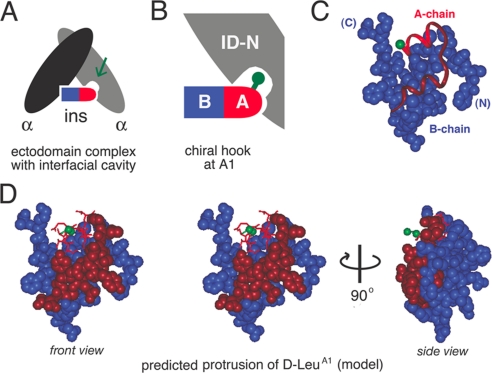

We next focused on d-amino acid substitutions at A1 because such substitutions have been shown to be well tolerated in insulin (44–47), whereas conventional l-substitutions markedly impair activity (48, 49). We hypothesized that in the hormone-receptor complex a cavity adjoins the pro-d Hα of GlyA1 (Fig. 4A). We further hypothesized that that cavity might exhibit receptor-specific differences between IR and IGFR associated with the difference between a two-chain ligand (insulin) or single-chain ligand (IGF-I). This model suggested that d-substitutions at A1 might function as a “chiral hook” to stabilize IR binding and destabilize IGFR binding (Fig. 4B). The crystal structure of wild-type insulin suggests that d-side chains at A1 would protrude from the protein surface (green in Fig. 4, C and D) in accord with the similarity between the crystal structures of l-TrpA1 and d-TrpA1 insulin analogs (47).

FIGURE 4.

Molecular model of putative A1-associated pocket. A, model of dimeric IR ectodomain (light and dark gray ovals) with bound insulin (bullet); the A-chain is red, and the B-chain is blue. B, expansion of right-hand binding interface showing predicted protrusion of d-amino acid side chain at position A1 into a gap at the hormone-receptor interface. The nonstandard residue may thus function as a chiral hook. C, position of A1 Cα (green ball) in A-chain (ribbon) in relation to space-filling model of B-chain (blue). The A1–A8 α-helix is red, and the remainder of the A-chain is maroon. D, molecular model of d-LeuA1. Left, stereo model showing d-LeuA1 (green) and A1–A8 α-helix (red) in relation to space-filling models of B-chain (blue) and remainder of the A-chain (maroon). Right, corresponding side view related by 90° rotation (arrow).

Three analogs of DabA8-insulin were prepared, containing either d-Ala, d-Leu or d-Asp at A1. The analogs exhibited similar far-ultraviolet CD spectra and thermodynamic stabilities (at 4 °C and pH 7.4; data not shown). Two-state modeling of the denaturation transitions yields estimates of 3.5 ± 0.1 kcal/mol (d-AlaA1), 3.7 ± 0.1 kcal/mol (d-AspA1), and 3.4 ± 0.1 kcal/mol (d-LeuA1); the respective stabilities of insulin and DabA8-insulin under these conditions are 4.1 ± 0.1 and 3.6 ± 0.1 kcal/mol (43). Each substitution at A1 was observed to augment the selectivity of DabA8-insulin (column 4 in Table 1). The mechanism by which this augmentation is achieved differs among the analogs. Whereas d-AlaA1 and d-AspA1 each impair IR binding by ∼2-fold, d-LeuA1 enhances IR binding by ∼3-fold (Fig. 3A and Table 1). d-LeuA1 enhances cross-binding to IGFR but to a smaller extent, yielding a net improvement in selectivity of 4.1 ± 0.8-fold; this exceeds our design target of 3 in relation to clinical hyperinsulinemia. d-AspA1 and d-AlaA1 by contrast reduce IGFR cross-binding to a greater extent than they impair IR binding (Fig. 3B and Table 1). This results in a similar augmentation of selectivity.

The in vivo biological potency of a representative analog ([d-AspA1,DabA8]insulin) was tested in Lewis rats rendered diabetic by prior treatment with streptozotocin (see supplemental material). The initial rate of fall in blood glucose concentration was measured for 60 min following subcutaneous injection of either human insulin or the analog at a submaximal dose (6.7 μg per rat; body weight ∼300 g). Although the in vitro affinity of [d-AspA1,DabA8]insulin for IR isoform B is 2-fold lower than that of wild-type insulin, their in vivo potencies were indistinguishable. Such bioequivalence is in accord with past studies of insulin analogs and attributed to compensating effects of the mutations on rates of insulin clearance.

Photocross-linking Studies

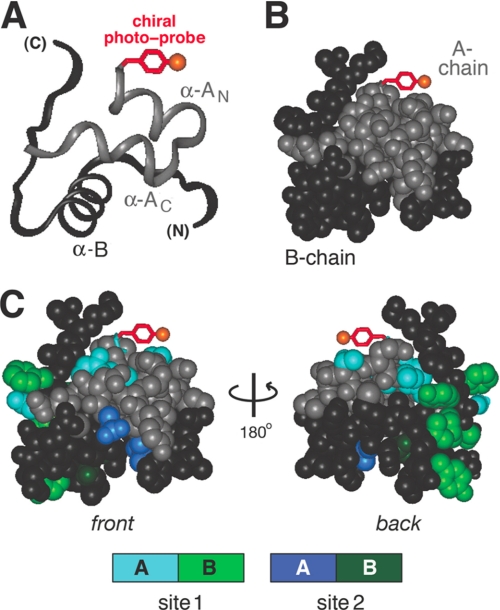

Protrusion of the d-side chain near the receptor interface was demonstrated by photocross-linking. To this end, a photoactivatable derivative of porcine insulin was prepared containing d-PapA1. The position of the probe relative to the receptor-binding surfaces of insulin (sites 1 and 2) is illustrated in Fig. 5. The derivative also contained a caproyl-linked biotin moiety attached to the A1 α-amino group. The IR binding affinity of the photostable d-para-amino-PheA1 precursor was 8 ± 1% relative to human insulin. Pap was chosen based on its rigidity and small size (relative to other photoactivatable moieties), thus limiting the distance range for cross-linking (32). The photocross-linking studies of the d-PapA1 analog were investigated in relation to previously characterized Pap analogs at positions B24 and B25 (25, 50). Because of the reduced activity of the photostable precursor, photocross-linking studies were performed at equimolar concentrations of the insulin derivative and receptor (200 nm) more than 2000-fold higher than the wild-type dissociation constant. Such high protein concentrations suggest that despite the likelihood of reduced binding affinity, the irradiated solutions contained predominantly 1:1 specific complexes representative of the native high affinity state (27).

FIGURE 5.

Design of photoactivatable insulin derivative. A, ribbon model of insulin T-state indicating possible position of d-PapA1 side chain (red). Orange ball indicates position of azido probe. The A- and B-chains are shown in light and dark gray. B, corresponding space-filling model with same coloring scheme. C, front and back surfaces of insulin (left and right) showing possible location of d-PapA1 probe relative to receptor-binding surfaces. In a model proposed by De Meyts and co-workers (70), insulin functions via two binding surfaces, designated site 1 and site 2. Site 1 is highlighted in powder blue (A-chain) and light green (B-chain); site 2 is depicted in dark blue (A-chain) and dark green (B-chain). Residues shown in site 1 are IleA2, ValA3, ThrA8, TyrA19, AsnA21, ValB12, TyrB16, GlyB23, PheB24, PheB25, and TyrB26; residues shown in site 2 are LeuA13, LeuA17, HisB10, AlaB14, and LeuB17. A- and B-chain surfaces are otherwise light and dark gray, respectively.

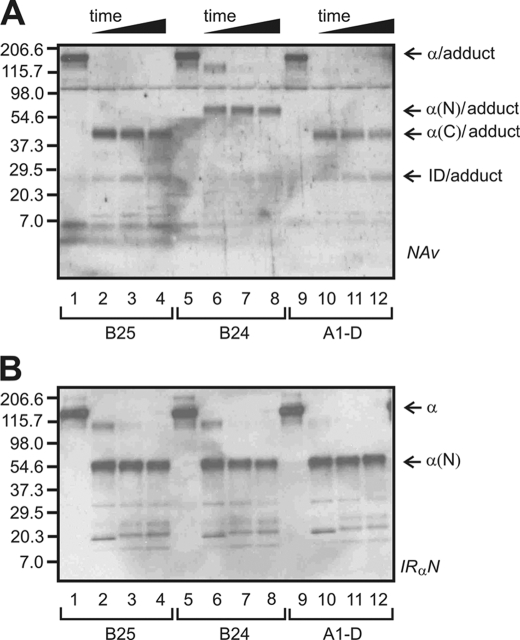

Following UV irradiation, the d-PapA1 analog exhibited rapid and efficient cross-linking to the WGA-purified IR (Fig. 6A, lanes 9–12). A similar pattern of photocross-linking was observed to the isolated IR ectodomain (data not shown). At least 10% of bound probes form covalent complexes as indicated by comparison with l-Pap derivatives at positions B24 or B25 (32). To identify the site of cross-linking in the IR, we employed partial proteolysis with chymotrypsin to characterize fragments of the α-receptor subunit covalently bound to Pap-insulin derivatives (Fig. 6, A and B). This protocol (32) exploits the modular domain organization of IR (Fig. 2B) and crystal structure of its ectodomain (Fig. 2, C and D). Because digestions were undertaken under native conditions, fragments reflect accessible chymotryptic sites within and between structural modules of the receptor; key sites are located within the cysteine-rich (CR) domain (Fig. 2B, arrow) and at the N-terminal junction of the insert domain (Fig. 2B, asterisk). The assay utilized an avidin-based reagent (neutravidin) to identify the A-chain cross-linked fragments (Fig. 6A) and likewise employed an antiserum to an N-terminal epitope (IRα-N) to identify N-terminal fragments of the receptor α-subunit (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Photocross-linking studies. Chymotryptic mapping of specific photocross-linked complexes: B25 (lanes 1–4), B24 (lanes 5–8), and A1(D chirality; lanes 9–12). A and B, fragments were blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane and detected by neutravidin (Nav) (A) or antiserum IRα-N (B). l-Pap derivatives at B24 and B25 provide controls indicative of photocross-linking to L1 and ID-N, respectively (26). The fragmentation pattern of the d-PapA1-cross-linked complex matches that of PapB25 (α(C) and ID adduct bands); the B24 cross-linked complex gives rise to distinct α(N) band and a faint smaller N-terminal band whose mobility is slightly slower than that of ID-N. Photoadducts were obtained at indicated positions and digested as described. At successive time points (32), aliquots were reduced, heat-denatured, and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Molecular masses and domain assignments are as indicated (37).

Two chymotryptic patterns have been characterized previously as follows: one corresponds to binding to the C-terminal tail of the α-subunit derived from the insert domain (as exemplified by cross-linking of a B25 probe), and the other corresponds to binding to the N-terminal L1 domain (as exemplified by cross-linking of a B24 probe; Fig. 6A, lanes 5–8). L1 and ID domains are shown in gray and orange in Fig. 2, C (ectodomain protomer) and D (ectodomain dimer); additional information regarding interpretation of the masses of photoproducts is provided as supplemental material. The present results indicate that photocross-linking of the d-PapA1 derivative conforms to the B25 pattern and hence cross-links the insert domain-derived tail of the receptor α-subunit (orange in Fig. 2, C and D). Analogous findings have been described in studies of l-PapA3 and l-PapA8 insulin analogs (26, 27) and were recently extended to PapA2 and PapA4 derivatives (37).

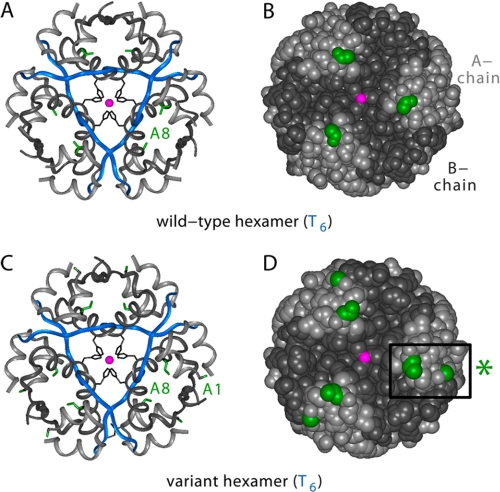

Structural Studies

[d-AlaA1,DabA8]human insulin was crystallized as a T6 zinc hexamer. The crystal structure was determined by molecular replacement to a resolution of 1.35 Å; data collection and refinement statistics are given in Table 2. The structures of the two variant protomers (designated molecules 1 and 2) are similar to each other and to wild-type protomers in the same crystal form; no significant changes are observed in secondary structure, chain orientation, or mode of assembly. As in wild-type T6 hexamers, zinc coordination is mediated by three symmetry-related HisB10 side chains with Zn2+-N distances of 2.08 Å (molecule 1) and 2.09 Å (molecule 2). Comparison between variant and wild-type T6 structures yields root-mean-square deviation values (excluding residues A1 and A8) of 0.91 Å (main chain) and 1.73 Å (side chains). These values are similar to those obtained in pairwise comparison between structures of wild-type insulin in different crystal forms.

Representative regions of electron density in molecules 1 and 2 are shown in Fig. 7 depicting the environment of d-AlaA1 (A and B) and DabA8 (C and D). In each case residues A1 and A8 adopt respective conformations similar to those of GlyA8 and ThrA8 in the wild-type T6 hexamer. Comparison of the wild-type and variant hexamers is shown in Fig. 8 in relation to ribbon models (A and C) and space-filling models (B and D). The side chains of d-AlaA1 and DabA8 (highlighted in green in Fig. 8, C and D) are each located on the surface of the hexamer (Fig. 8D). The variant surface sites are not associated with transmitted conformational changes.

FIGURE 7.

Crystallographic analysis of [d-AlaA1,DabA8]insulin. Representative electron density of variant insulin: 2Fo − Fc maps plotted at 1σ. A and B, neighborhood of d-AlaA1 in molecule 1 (A) and molecule 2 (B). The Cβ density of d-AlaA1 is labeled A1-Cβ, and its α-amino group is labeled A1-N. Water molecules are designated W“ C and D, neighborhood of DabA8 in molecules 1 and 2.

FIGURE 8.

Crystal structures of wild-type and variant T6 zinc hexamers. A and B, structure of wild-type hexamer: ribbon model (A) and space-filling model (B). In the ribbon model, the A-chain is shown in light gray, and the B-chain is in blue (B1–B8) or dark gray (B9–B30). The A8 side chain is shown in green, B10 side chain in black, and axial zinc ions (superimposed) in magenta. The coloring scheme in the space-filling model is the same except that the B-chain is dark gray throughout. C and D, structure of [d-AlaA1,DabA8]insulin hexamer: ribbon model (C) and space-filling model (D). The coloring scheme is the same as in A and B with the addition of d-AlaA1 methyl group (green). Box at right indicates variant A1 and A8 sites in one protomer.

DISCUSSION

The vertebrate insulin-related family consists of insulin and insulin-related growth factors (IGF-I and IGF-II) (51, 52). Insulin and IGFs function as ligands for receptor tyrosine kinases (the insulin receptor and class I IGF receptor (16, 53). Whereas insulin contains two chains (as the proteolytic product of proinsulin), IGFs are single-chain polypeptides containing A and B domains, an intervening connecting (C) domain, and C-terminal D domain (51, 52). Insulin, IGF-I, and IGF-II each bind to IR (isoforms A and B) and IGFR but with different relative affinities. In this study, we have described the design of an insulin analog with enhanced selectivity for IR. We anticipate that this and related analogs will provide valuable reagents for studies of cellular proliferation (15) and carcinogenesis associated with hyperinsulinemia (4).

The functional surfaces of insulin and IGF-I contain corresponding recognition α-helices (residues A1–A8 and B9–B19). A substitution in the B-chain α-helix (HisB10 → Asp) enhances the activity of insulin but also enhances cross-binding to the IGF receptor (54–56), presumably due to electrostatic mimicry of IGF-I (which has Glu at this position; residue 7 in IGF-I). This analog exhibits increased mitogenicity and is associated with carcinogenesis in a rat model.5 By contrast, the present results demonstrate that nonstandard modification of the A-chain α-helix can enhance binding to the IR with reduced binding to the IGF receptor. 4-Fold enhanced selectivity was achieved, corresponding to absolute discrimination ratios of 333 ± 36 (wild-type insulin) and 1375 ± 150 ([d-LeuA1,d-DabA8]insulin). Such enhancement is of interest in relation to the pathological consequences of hyperinsulinemia wherein time-integrated postprandial insulin concentrations are typically increased by 3-fold. The high resolution crystal structure of the variant is essentially identical to that of native insulin (49).

Protein design was based on introduction of nonstandard N- and C-capping residues at positions A1 and A8. The substitutions exploit differences between insulin and IGF-I at these sites. At A8 human insulin contains Thr, whereas IGF-I contains a grossly dissimilar side chain (Phe49). The utility of A8 substitutions to enhance the selectivity of insulin was suggested by the following: (i) the proximity of this site to the receptor interface as indicated by photocross-linking studies (26); (ii) the tolerance at this site of diverse side chains (43); and (iii) its role in distinguishing between IR and IGFR (19). We chose to introduce DabA8 because this residue is well tolerated by IR (43) but disproportionately impairs binding to IGFR (Table 1). Prior crystallographic studies (at the intermediate resolution of 2.1 Å) had documented the absence of transmitted perturbations (43). DabA8-insulin thus provided a platform for further modification.

Gly is conserved at A1 in both insulin and IGF-I (residue 42). Yet in insulin, GlyA1 adjoins a free α-amino group, whereas in IGF-I, Gly42 is part of single polypeptide chain. Furthermore, the N-terminal modification of the insulin A-chain or its N-terminal extension impairs IR binding (48, 49, 57, 58). These salient differences suggested IR and IGFR differ near otherwise homologous A1 sites. Our focus on d-amino acid substitutions was motivated by the loss of activity associated with conventional l-substitutions but high activity of d-analogs. Side chains as large as d-TrpA1 are well tolerated. Such stereospecificity suggested that the pro-d α-hydrogen of GlyA1, unlike its pro-l α-hydrogen, adjoins a cavity in the hormone-receptor complex. Substitution of GlyA1 by the photoactivatable residue d-Pap results in specific receptor cross-linking; the site of contact (the C-terminal segment of the α-subunit) is similar to those mapped in previous studies of l-PapB25 derivatives (25, 32) and corresponding photoactivatable derivatives at positions A3 and A8 (26, 27, 59).

We hypothesized that the presence of an interfacial cavity adjoining GlyA1 provides an opportunity to introduce novel binding interactions. Whereas insertion of d-AspA1 or d-AlaA1 impairs binding by ∼2-fold, d-LeuA1 augments affinity by almost 3-fold. From a structural perspective, we envisage that the larger nonpolar d-side chain provides a chiral hook to repair a packing defect otherwise intrinsic to the structure of the receptor interface. Combined substitution of GlyA1 by d-Leu and ThrA8 by diaminobutyric acid thus gives an analog of enhanced affinity and receptor selectivity. This class of analogs may enable dissection of receptor-specific signaling pathways in vitro and may be of potential therapeutic interest in diabetes mellitus. Insulin analogs with in vitro IR affinities in the range observed here (Table 1) typically exhibit biological potencies in directing glucose disposal similar to that of wild-type insulin as demonstrated in a diabetic rat model for [d-AspA1,DabA8]insulin (supplemental Fig. S1). It is therefore possible that the d-AspA1 or d-AlaA1 analogs might be preferable in vivo to [d-LeuA1,DabA8]insulin based on the criterion of lower IGFR cross-binding.

Epidemiological studies have shown that risk factors for CRC cancer (obesity, sedentary life style, and a diet rich in animal fats and low in vegetables) overlap with risk factors for the metabolic syndrome (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and hyperinsulinemia leading to impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 DM) (60). The molecular links between these factors and carcinogenesis are not well understood. In past decades, hypotheses have focused on exposure time of colonic epithelia to carcinogens in stool, itself related to intestinal transit time and dietary composition. A critique of these models has been published (61). Current models focus on aberrant overactivation of the IGF signaling system in the self-renewing compartment of colonic crypts and at each stage of neoplasia (15, 62). This perspective is in accord with the general importance of IGFR-mediated signaling in tumorigenesis, mediated by both the autocrine and paracrine actions of IGF-I and IGF-II (63). Direct and indirect effects of IGFR-mediated signaling modulates mammalian target of rapamycin-, Ras-, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-, and Wnt-related cascades to influence both rates of proliferation and apoptosis (64). Such effects have stimulated pharmaceutical interest in the development of IGFR inhibitors (65, 66).

The association between hyperinsulinemia and CRC may be mediated by the local binding of insulin to IGFR in colorectal epithelia or by downstream effects of insulin signaling to increase the bioavailability of free IGF-I (5, 12). Distinguishing between these potential mechanisms is presently difficult. Insulin analogs with enhanced selectivity for the IR may enable definitive studies in animal models of CRC tumorigenesis and progression (4, 15). Because pharmacological hyperinsulinemia incurred in the treatment of type 2 DM (either through the administration of exogenous insulin or secretagogues) is also associated with an increased risk of CRC (6–9), such studies may enhance the safety of insulin therapy in patients at risk for CRC.6 The relationship between hyperinsulinemia and CRC exemplifies the general association between obesity and cancer (67), a public health issue of increasing importance (68).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ying-Chi Chu and Shi-Quan Hu for assistance with synthesis of photoreactive insulin analogs; W. Jia for CD studies, and Q. X. Hua for assistance with figures.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK065890 (to J. W.) and DK40949 and DK074176 (to M. A. W.). This article is a contribution from the Cleveland Center for Structural Biology.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3FQ9) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Experimental Procedures,” Fig. S1, and additional references.

Treatment of Sprague-Dawley rats with AspB10-insulin was observed to be associated with an increased rate of mammary tumors (56). Cell culture studies have established that AspB10-insulin enhances the proliferation of human breast cancer cell lines relative to wild-type insulin (55). Its increased mitogenicity may be due either to IGFR cross-binding or to a prolonged IR residence time (69).

Since the submission of this article, a cohort study of >120,000 patients in Germany has suggested a dose-dependent association between treatment with insulin glargine (LantusTM) and diverse human cancers, including neoplasias of the colon, pancreas, breast, and prostate (71). Insulin glargine contains a dibasic extension of the B-chain (ArgB31–ArgB32) that enhances cross-binding to IGFR and a substitution in the A-chain (AsnA21 → Gly) that reduces affinity for IR. Unlike other insulin analogs in current clinical use (such as AspB28-insulin (insulin aspart) or LysB28–ProB29-insulin (insulin lispro)), insulin glargine thus exhibits reduced receptor selectivity. The statistical methods and conclusions of the cohort study (71) have been brought into question (72).

- DM

- diabetes mellitus

- Dab

- diaminobutyric acid

- IGF

- insulin-like growth factor

- IGFR

- type 1 IGF receptor

- IR

- insulin receptor

- Pap

- para-azido-phenylalanine

- CRC

- colorectal cancer

- WGA

- wheat germ agglutinin

- IRα-N

- N-terminal segment of the receptor α-subunit

- CR

- cysteine-rich

- T6

- zinc insulin hexamer comprising six T-state protomers. Amino acids are designated by standard one- and three-letter codes and indicate the l isomer unless otherwise specified.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saydah S. H., Loria C. M., Eberhardt M. S., Brancati F. L. (2003) Am. J. Epidemiol. 157, 1092–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berster J. M., Göke B. (2008) Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 114, 84–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LeRoith D., Novosyadlyy R., Gallagher E. J., Lann D., Vijayakumar A., Yakar S. (2008) Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 116, S4–S6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donovan E. A., Kummar S. (2008) Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 66, 91–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollak M. (2008) Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 915–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Y. X., Hennessy S., Lewis J. D. (2004) Gastroenterology 127, 1044–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowker S. L., Majumdar S. R., Veugelers P., Johnson J. A. (2006) Diabetes Care 29, 254–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung Y. W., Han D. S., Park K. H., Eun C. S., Yoo K. S., Park C. K. (2008) Dis. Colon Rectum 51, 593–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monami M., Lamanna C., Pala L., Bardini G., Cresci B., Francesconi P., Balzi D., Marchionni N., Rotella C. M., Mannucci E. (2008) Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 116, 184–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amos A. F., McCarty D. J., Zimmet P. (1997) Diabet. Med. 14, S1–S85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wild S., Roglic G., Green A., Sicree R., King H. (2004) Diabetes Care 27, 1047–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renehan A. G., Frystyk J., Flyvbjerg A. (2006) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 17, 328–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heald A., Stephens R., Gibson J. M. (2006) Diabet. Med. 23, Suppl. 1, 19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samani A. A., Yakar S., LeRoith D., Brodt P. (2007) Endocr. Rev. 28, 20–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran T. T., Naigamwalla D., Oprescu A. I., Lam L., McKeown-Eyssen G., Bruce W. R., Giacca A. (2006) Endocrinology 147, 1830–1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Meyts P., Whittaker J. (2002) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1, 769–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brzozowski A. M., Dodson E. J., Dodson G. G., Murshudov G. N., Verma C., Turkenburg J. P., de Bree F. M., Dauter Z. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 9389–9397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lou M., Garrett T. P., McKern N. M., Hoyne P. A., Epa V. C., Bentley J. D., Lovrecz G. O., Cosgrove L. J., Frenkel M. J., Ward C. W. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 12429–12434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gauguin L., Klaproth B., Sajid W., Andersen A. S., McNeil K. A., Forbes B. E., De Meyts P. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 2604–2613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Z., Bodkin N. L., Ortmeyer H. K., Hansen B. C., Shuldiner A. R. (1994) J. Clin. Invest. 94, 1289–1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kristensen C., Kjeldsen T., Wiberg F. C., Schäffer L., Hach M., Havelund S., Bass J., Steiner D. F., Andersen A. S. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 12978–12983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gauguin L., Delaine C., Alvino C. L., McNeil K. A., Wallace J. C., Forbes B. E., De Meyts P. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20821–20829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nanjo K., Sanke T., Kondo M., Nishimura S., Miyano M., Linuma J., Miyamura K., Inouye K., Given B. D., Polonsky K. S., et al. (1986) Trans. Assoc. Am. Physicians 99, 132–142 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denley A., Wang C. C., McNeil K. A., Walenkamp M. J., van Duyvenvoorde H., Wit J. M., Wallace J. C., Norton R. S., Karperien M., Forbes B. E. (2005) Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 711–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurose T., Pashmforoush M., Yoshimasa Y., Carroll R., Schwartz G. P., Burke G. T., Katsoyannis P. G., Steiner D. F. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 29190–29197 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wan Z., Xu B., Huang K., Chu Y. C., Li B., Nakagawa S. H., Qu Y., Hu S. Q., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 16119–16133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wan Z. L., Huang K., Xu B., Hu S. Q., Wang S., Chu Y. C., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 5000–5016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katsoyannis P. G. (1966) Science 154, 1509–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kochendoerfer G. G., Kent S. B. (1999) Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 3, 665–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang L., Xie J., Schultz P. G. (2006) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 35, 225–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakagawa S. H., Tager H. S. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 11502–11509 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu B., Hu S. Q., Chu Y. C., Huang K., Nakagawa S. H., Whittaker J., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 8356–8372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss M. A., Hua Q. X., Jia W., Chu Y. C., Wang R. Y., Katsoyannis P. G. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 15429–15440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sosnick T. R., Fang X., Shelton V. M. (2000) Methods Enzymol. 317, 393–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whittaker J., Whittaker L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 20932–20936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whittaker J., Groth A. V., Mynarcik D. C., Pluzek L., Gadsbøll V. L., Whittaker L. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43980–43986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu B., Huang K., Chu Y. C., Hu S. Q., Nakagawa S., Wang S., Wang R. Y., Whittaker J., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14597–14608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones T. A., Zou J. Y., Cowan S. W., Kjeldgaard M. (1991) Acta Crystallogr. A 47, 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laskowski R. A., Macarthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., Warren G. L. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laskowski R. A. (1995) J. Mol. Graph. 13, 323–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaarsholm N. C., Norris K., Jørgensen R. J., Mikkelsen J., Ludvigsen S., Olsen O. H., Sørensen A. R., Havelund S. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 10773–10778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss M. A., Wan Z., Zhao M., Chu Y. C., Nakagawa S. H., Burke G. T., Jia W., Hellmich R., Katsoyannis P. G. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 315, 103–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geiger R., Geisen K., Summ H. D., Langer D. (1975) Hoppe Seylers Z. Physiol. Chem. 356, 1635–1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cosmatos A., Cheng K., Okada Y., Katsoyannis P. G. (1978) J. Biol. Chem. 253, 6586–6590 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geiger R., Geisen K., Summ H. D. (1982) Hoppe Seylers Z. Physiol. Chem. 363, 1231–1239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wan Z. L., Liang D. C. (1988) Sci. China B 31, 1426–1438 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krail G., Brandenburg D., Zahn H. (1975) Hoppe Seylers Z. Physiol. Chem. 356, 981–996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baker E. N., Blundell T. L., Cutfield J. F., Cutfield S. M., Dodson E. J., Dodson G. G., Hodgkin D. M., Hubbard R. E., Isaacs N. W., Reynolds C. D. (1988) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 319, 369–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shoelson S. E., Lee J., Lynch C. S., Backer J. M., Pilch P. F. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 4085–4091 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rotwein P., Pollock K. M., Didier D. K., Krivi G. G. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 4828–4832 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dull T. J., Gray A., Hayflick J. S., Ullrich A. (1984) Nature 310, 777–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adams T. E., Epa V. C., Garrett T. P., Ward C. W. (2000) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57, 1050–1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwartz G. P., Burke G. T., Katsoyannis P. G. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 6408–6411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Milazzo G., Sciacca L., Papa V., Goldfine I. D., Vigneri R. (1997) Mol. Carcinog. 18, 19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brange J., Vølund A. (1999) Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 35, 307–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katsoyannis P. G., Zalut C. (1972) Biochemistry 11, 1128–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kohn W. D., Micanovic R., Myers S. L., Vick A. M., Kahl S. D., Zhang L., Strifler B. A., Li S., Shang J., Beals J. M., Mayer J. P., DiMarchi R. D. (2007) Peptides 28, 935–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang K., Chan S. J., Hua Q. X., Chu Y. C., Wang R. Y., Klaproth B., Jia W., Whittaker J., De Meyts P., Nakagawa S. H., Steiner D. F., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 35337–35349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Giovannucci E. (2001) J. Nutr. 131, S3109–S3120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Giovannucci E. (1995) Cancer Causes Control 6, 164–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sandhu M. S., Dunger D. B., Giovannucci E. L. (2002) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 94, 972–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pollak M. (2008) Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 22, 625–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun J., Jin T. (2008) Cell. Signal. 20, 219–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clemmons D. R. (2007) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 821–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weroha S. J., Haluska P. (2008) J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 13, 471–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Calle E. E., Rodriguez C., Walker-Thurmond K., Thun M. J. (2003) N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1625–1638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Calle E. E., Kaaks R. (2004) Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 579–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berti L., Kellerer M., Bossenmaier B., Seffer E., Seipke G., Häring H. U. (1998) Horm. Metab. Res. 30, 123–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.De Meyts P., Gu J. L., Shymko R. M., Kaplan B. E., Bell G. I., Whittaker J. (1990) Mol. Endocrinol. 4, 409–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hemkens L. G., Grouven U., Bender R., Günster C., Gutschmidt S., Selke G. W., Sawicki P. T. (2009) Diabetologia 52, 1732–1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pocock S. J., Smeeth L. (2009) Lancet 374, 511–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.