Abstract

Background

As of 1 April 2007, pharmacists in Germany filling prescriptions covered by the statutory health insurance system (Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung, GKV) are required, whenever possible, to dispense a preparation that contains the same active substance and for which a rebate contract is in effect. The physician can block drug substitution by crossing out “aut idem” (“or the like”) on the prescription form. The latter option has existed since 2002. We studied the possible effect of the introduction of rebate contracts on the use of the no-substitution option.

Methods

Three independent random samples were taken from the routine data of the Gmünder ErsatzKasse (GEK, a statutory health insurance carrier). The samples consisted of 0.5% of the insured adult population in the month of October in the years 2006, 2007, and 2008 (n = 6195; n = 6300; n = 6845). Within these sample groups, all medication orders in which the physician could potentially have exercised a no-substitution option were selected, and the corresponding prescriptions were examined.

Results

The percentage of no-substitution prescriptions rose from October 2006 to October 2007, and then rose still further to October 2008 (14.4%, 18.4%, 19.0%; p for trend < 0.0001). Considerable differences were seen between physicians belonging to different regional Associations of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (Kassenärztliche Vereinigungen). In about one-quarter of the no-substitution prescriptions for 2007 and 2008 (25.1%, 25.7%), the prescribed medication was itself included in a rebate contract.

Conclusions

The use of the no-substitution option is not uniform across Germany at present. Rebate contracts and the no-substitution option require further evaluation. Moreover, the dispensing of medications urgently needs a more stable regulatory framework.

Keywords: drug prescribing, drug prices, no substitution, competition, generic drugs

The SHI Competition Strengthening Act (GKV-Wettbewerbsstärkungsgesetz, GKV-WSG) went into effect in Germany on 1 April 2007. This law was the decisive step enabling statutory health insurance (SHI [Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung, GKV]) carriers to make rebate contracts with pharmaceutical companies. By December 2008, 215 insurance carriers had established a total of 5777 rebate contracts with 116 pharmaceutical companies under the provisions of §130a Abs. 8 SGB V (i.e., §130a Para. 8 of the German Social Security Code, Chapter V). This was an increase of 80.9% over December 2007 (1).

The GKV-WSG requires pharmacies to fill prescriptions for a drug containing a specific active substance with a generic drug containing the same active substance that is covered by a rebate contract, whenever this is possible. The only permissible reasons for not doing so are:

the absence of a rebate contract,

the manufacturer’s inability to deliver the drug,

the presence of “pharmaceutical concerns,”

an urgent need to dispense the medication immediately (emergency service, acute care),

a specification by the SHI physician that no substitutions are allowed (2).

The physician can block the substitution of a generic equivalent for the prescribed drug by crossing out the Latin words “aut idem” (“or the like”), which are printed on the prescription form. In this way, the physician retains the power to determine the particular preparation to be taken by the patient. On the other hand, rebated drugs receive special consideration in efficiency evaluations (Wirtschaftlichkeitsprüfungen). By prescribing a rebated drug and simultaneously specifying “no substitution,” the physician can retain decision-making ability over prescriptions, while also lessening expenditures.

The physician’s option of specifying “no substitution” has existed ever since the Act for the Limitation of Drug Expenses (Arzneimittelausgaben-Begrenzungsgesetz, AABG) went into effect in 2002. The “old” regulations required pharmacists to dispense one of the three least expensive preparations containing the active substance in question, or else the preparation that was prescribed by name. This is still the case if the patient’s insurance carrier has no rebate contract for a drug that contains this active substance. The effects of rebate contracts on patients and on the everyday practice of physicians in the statutory health insurance system have been discussed previously in the Deutsches Ärzteblatt (3, 4).

The goal of the present study is to determine whether the introduction of rebate contracts has led to a change in the utilization of the “no substitution” option, and thus in the “cross-out habits” of doctors who may, at their discretion, choose to cross out “aut idem” on the prescription form.

Methods

This study was performed on the basis of drug claims data of the Gmünder ErsatzKasse (GEK), a statutory health insurance (SHI) carrier that had a market share of ca. 2.4% across Germany as of October 2008. To analyze the effects of rebate contracts, the authors took three independent random samples comprising 0.5% of all GEK-insured adults in October 2006, 2007, and 2008 (1.24 million, 1.26 million, and 1.37 million persons, respectively; the samples thus comprised 6195, 6300, and 6845 persons). Three samples from the same month (October) were chosen in order to exclude possible seasonal effects. Children and adolescents were excluded from consideration, as their pharmacological treatment spectrum differs considerably from that of adults, and a homogeneous patient collective was desired.

Once the sample populations had been generated, all of their prescriptions in which “no substitution” could have been specified were selected from the three months under study. The scanned images of the prescriptions, which were in the possession of the health insurance carrier, were then visually inspected by a GEK employee on the premises of the GEK. (A word of explanation: Prescriptions filled in public pharmacies and billed to SHI carriers are scanned and electronically stored in [mostly regional] pharmacy data processing centers, and the prescriptions themselves, the images, and the electronic data are all forwarded to the carrier. A more detailed description of the flow of prescriptions and related data can be found in Hoffmann et al. [5].) When inspecting the prescriptions, the GEK employee determined whether the SHI physician had crossed out “aut idem” on the prescription form in order to indicate that there should be no drug substitution by the pharmacist.

The variable under study was the percentage of prescriptions (independent of the number of prescribed packages) in which “no substitution” had been specified in this manner. Chi-square tests were used to study linear trends over time in the years 2006 through 2008. All p-values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The SAS software package, Version 9.2, was used for data analysis.

Results

Just over half of the patients in all three samples were male (2006, 53.9%; 2007, 53.1%; 2008, 53.3%). The average age of all patients was 45 years (44.5, 44.8, and 45.5 years in 2006, 2007, and 2008). A total of 9154 prescriptions were inspected (n = 2624; n = 2981; n = 3549). 17 of these prescriptions were excluded because the crossing out of “aut idem” on the form was ambiguously placed or otherwise illegible. Thus, a total of 9137 prescriptions were available for evaluation.

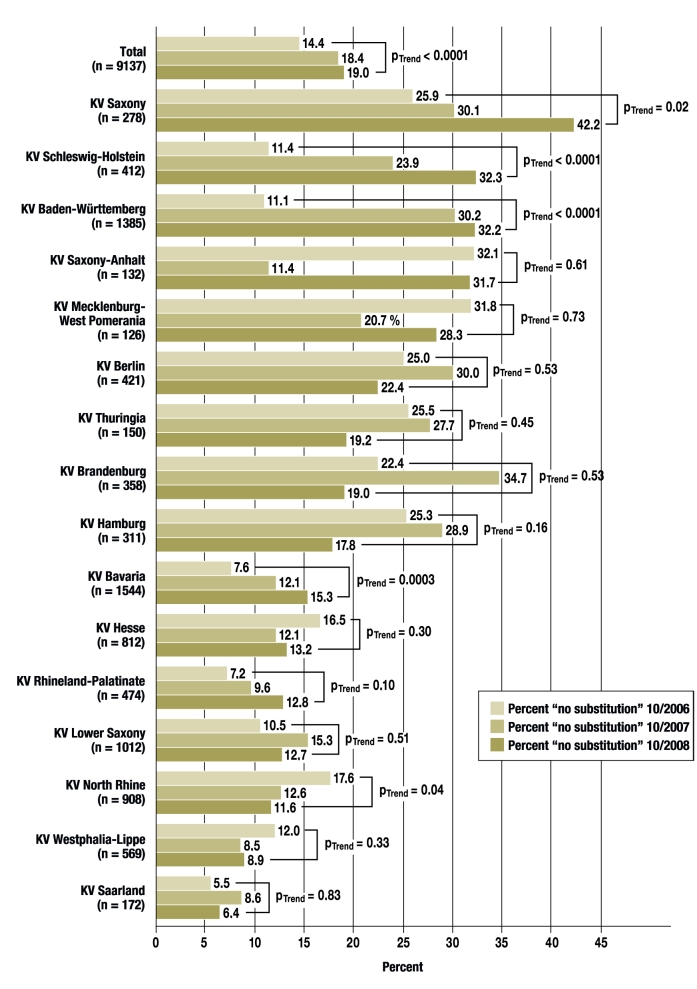

The percentage of prescriptions for which the physician specified “no substitution” increased overall during the period of the study, from 14.4% in 2006 to 18.4% in 2007 and 19.0% in 2008 (p<0.0001 for the trend). As the Figure shows, however, there were major differences and highly variable patterns from one KV region to another (KV, Kassenärztliche Vereinigung [Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians]). This variability was already evident in October 2006, when the number of “no substitution” prescriptions was 5.5% in the KV Saarland, but 32.1% in the KV Saxony-Anhalt. The corresponding range of variability in October 2008 was from 6.4% (KV Saarland) to 42.2% (KV Saxony). Notably, the percentage of “no substitution” prescriptions over the years tended to be markedly higher in areas belonging to the former East Germany than in the remainder of the country. A steady decrease in “no substitution” prescriptions was seen in only one KV region, the KV North Rhine (from 17.6% to 12.6% and then 11.6%, p = 0.04 for the trend). On the other hand, marked linear rises in the percentage of “no substitution” prescriptions were seen in the KV regions Schleswig-Holstein (11.4%—23.9% —32.3%, p<0.0001 for the trend) and Baden-Württemberg (11.1%—30.2%—32.2%, p<0.001 for the trend), as well as in Bavaria.

Figure 1.

The percentage of prescriptions with the specification “no substitution,” by KV region (KV, Kassenärztliche Vereinigung [Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians]. The KV Bremen is not displayed separately because the sample size is too small.

Differences in prescribing practices among the most commonly prescribed active substances (table) were less pronounced than interregional differences. Notable patterns were seen in the percentage of “no substitution” prescriptions for levothyroxine (13.6%—13.2%—29.2%, p = 0.001 for the trend) and simvastatin (9.4%—20.0%—23.0%, p = 0.048 for the trend). For both of these drugs, the percentages in 2008 were more than twice what they were in 2006.

Table. The percentage of prescriptions with the specification “no substitution” for the most commonly prescribed active substances.

| Percentage “no substitution” | ||||

| Active substance | 10/2006 | 10/2007 | 10/2008 | p-value for trend |

| Diclofenac (n = 422) | 11.9% | 18.5% | 18.3% | p = 0.15 |

| Levothyroxine (n = 369) | 13.6% | 13.2% | 29.2% | p = 0.001 |

| Metoprolol (n = 303) | 14.4% | 24.7% | 21.6% | p = 0.25 |

| Ibuprofen (n = 300) | 13.8% | 12.0% | 19.7% | p = 0.19 |

| Omeprazole (n = 273) | 16.0% | 16.0% | 21.4% | p = 0.31 |

| Simvastatin (n = 255) | 9.4% | 20.0% | 23.0% | p = 0.048 |

| Bisoprolol (n = 218) | 20.3% | 20.5% | 24.7% | p = 0.52 |

| Ramipril (n = 198) | 14.8% | 20.3% | 18.8% | p = 0.60 |

| Metformin (n = 197) | 17.9% | 27.0% | 19.2% | p = 0.95 |

| Metamizole (n = 186) | 14.6% | 17.2% | 14.9% | p = 0.99 |

General practitioners and internists wrote a total of 80% of the prescriptions studied for which a “no substitution” option could have been excercised. No difference was seen between physicians in these specialties on the one hand, and all other physicians on the other, in any of the three years studied (for 2006, 14.3% vs. 14.8%, p = 0.77; for 2007, 18.2% vs. 19.2%, p = 0.57; for 2008, 19.3% vs. 18.3%, p = 0.59).

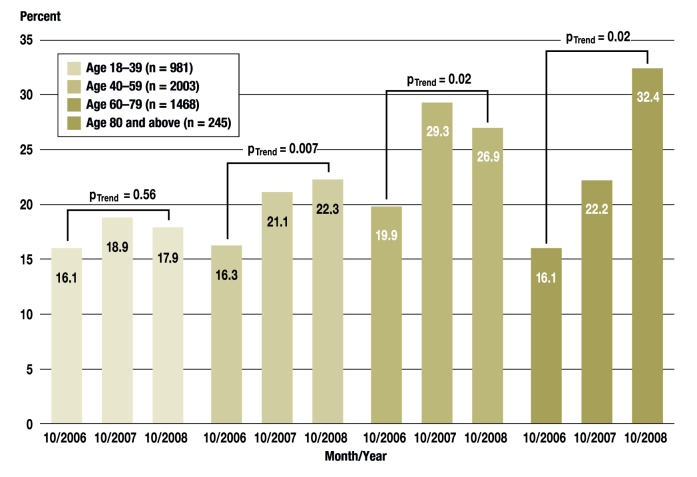

We also studied whether “no substitution” was more commonly specified for patients in specific age groups. To answer this question, we considered only persons who received at least one prescription in which a “no substitution” option could have been excercised during the study month in question (n = 4697). In October 2006, the percentage of insurees who had received at least one prescription in which “no substitution” was specified was comparable in all age groups, with values ranging from 16.1% to 19.9% (efigure). A linear increase from 2006 to 2008 was seen in all age groups except in persons aged 18 to 39. This trend is particularly evident in persons aged 80 or older (16.1%—22.2%—32.4%, p = 0.02 for trend).

eFigure.

The percentage of insurees with prescriptions with a possible “no substitution” option who received at least one prescription with “no substitution” specified, classified by age group

In both October 2007 and October 2008, one-quarter of all prescriptions in which “no substitution” was specified were for a medication covered by a rebate contract (25.1% and 25.7%, respectively).

Discussion

The findings of this study show that the introduction of rebate contracts was followed by a mild increase in the percentage of prescriptions in which the SHI physician specified “no substitution.” Both an age-specific trend and marked interregional differences are evident. The increase in the percentage of “no substitution” prescriptions was particularly marked for elderly patients. We interpret this as reflecting the SHI physicians’ reaction to the altered regulatory framework and the individual situation of these patients. In contrast to younger persons, the elderly take more medications (including medications for which substitution might cause difficulties) and have more trouble telling their various medications apart. This can lead to inadvertent switching or multiple intake. The SHI physicians seem to have made use of the “no substitution” rules specifically for these vulnerable patients, in order not to diminish the safety of their treatment.

In October 2008, the percentage of “no substitution” prescriptions varied, depending on the KV region of the SHI physician, from 6.4% (KV Saarland) to 42.2% (KV Saxony). This finding was unexpected and may be due to differences in the recommendations of the regional Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (KV) (6). An unsystematic Internet search revealed, however, that both the KV Saarland (7) and the KV Saxony (8) recommend prescribing generic drugs or active substances while permitting substitution, i.e., not crossing out “aut idem” on the prescription form. It seems likely that other factors and processes including, for example, differences in information, continuing education, and advice to physicians, exerted a more important influence in this respect.

Analyses by INSIGHT Health (9) und IMS Health (6, 10) also revealed comparable variability. An up-to-date study by INSIGHT Health shows that the percentage of “no substitution” prescriptions rose from the first to the second quarter of 2008 independently of the prescriber’s KV region (9). These analyses are based on a nearly complete evaluation of all SHI prescriptions and are thus much more comprehensive than the present study. Our study, however, has the major advantage that we have not relied on electronic detection of the prescriber’s having crossed out the “aut idem” field on the prescription form. With the direct inspection of all prescriptions serving as a basis for comparison, it turned out that the crossing-out of the “aut idem” field was correctly electronically detected (sensitivity) in merely 52.9% of prescriptions with “aut idem” crossed out in October 2006. On the other hand, among all of the prescriptions for which claims data stated that “aut idem” was crossed out, this accorded with the actual information on the prescription in only 40.1% (positive predictive value). Although electronic detection in the pharmacy data processing centers had improved somewhat by October 2008, a large number of “no-substitution” prescriptions were still not being adequately captured at that time: of 100 such prescriptions, the “no-substitution” status was electronically detected in only 80 (sensitivity: 79.8%). The positive predictive value of electronic detection in October 2008 was 92.1%. The authors again found a marked variation in data quality among pharmacy data processing centers that processed prescriptions electronically (11).

The drawback of our method is that the analyses by KV region, by active substance, or by medical specialty (for example) are based on relatively small samples of limited statistical power. In general, the findings of different studies on the percentage of prescriptions that were of the “no substitution” type are hard to compare directly, beyond merely noting common trends; this is so because the denominators used may differ—e.g., all prescriptions, only prescriptions for proprietary medicinal products, or only prescriptions for which “no substitution” was a potential option. We chose the last-named among the possible denominators in order to include all preparations for which substitution was possible.

In general, SHI physicians tend to think that rebate contracts have almost no influence on their therapeutic decisions (12, 13). According to a poll of 1050 SHI physicians that was taken by the KV North Rhine, 86% considered the implementation of rebate contracts to be the pharmacist’s responsibility (13). More than two-thirds of respondents (69%), however, were of the opinion that rebate contracts influenced their patients’ compliance. From the physicians’ point of view, they have found themselves in an increasingly unclear situation since the rebate contracts were introduced (12, 13). For the situation to improve, a stable legal regulatory environment for the prescribing of pharmaceuticals will be necessary, as well as a greater quantity of information delivered in timely fashion. In the current regulatory framework, SHI physicians prescribing medications that are available in generic form have four different options whose advantages and disadvantages have to be carefully considered in each case, and these will be discussed in turn in the following sections.

Prescriptions without the specification “no substitution”

When the SHI physician does not specify “no substitution,” he or she leaves the choice of preparation up to the pharmacist. When this is done, and the patient’s health insurance carrier does not have a rebate contract for a drug with the active substance in question, the pharmacist will dispense either one of the three least expensive drugs with this active substance, or else the drug named on the prescription. On the other hand, if there is a rebate contract, then the drug covered by the rebate contract will be dispensed. If there are multiple rebate contracts with different pharmaceutical companies for drugs with a given active substance, then the pharmacist can freely choose which of these drugs to dispense. In this state of affairs, the SHI physician cannot know which preparation the patient will actually receive. Especially in the case of medications taken over the long term, the issuing of further prescriptions for the same medication might result in an unintended change of drug preparation. On the other hand, prescribing without specifying “no substitution” also relieves the SHI physician of a burden: he or she no longer has to choose a particular preparation and need only order the active substance, the dose, and the size of the package. Furthermore, rebated drugs receive special consideration in efficiency evaluations. If a rebate contract exists with only a single manufacturer (for example, the rebate contracts of the health insurance company AOK that went into effect on 1 June 2009), then a physician prescribing the rebated drug will (indirectly) retain therapeutic decision-making ability while leaving the responsibility for cost-efficiency to others, while the patient receives the exact drug prescribed for as long as the rebate contract remains in effect.

Prescription of a generic drug covered by a rebate contract with the specification “no substitution”

This constellation has two advantages for the SHI physician: he or she chooses the precise preparation to be dispensed—at least, within a certain delimited framework—and is also spared further difficulties arising from efficiency evaluation. A necessary precondition, however, is that the software used by the physician must be updated with current information on the existing rebate contracts at least once per month. If multiple-drug contracts are in effect, then patients taking multiple medications can be treated with a group of drugs that are all manufactured by the same company. On the other hand, if rebate contracts are short-lived, then the continuity of long-term medication is no longer assured.

Prescription of an inexpensive generic drug not covered by a rebate contract with the specification “no substitution”

In this constellation, too, the SHI physician chooses the preparation to be dispensed, and the continuity of long-term medication may also be better assured than when rebated drugs are prescribed. Cost-efficiency need not necessarily suffer, as it is evident that many health insurance carriers make rebate contracts with higher-priced manufacturers as well. If more than one rebate contract is in effect for a given active substance, then there are many reasons why the physician or pharmacist, in either of the two constellations discussed above, might choose a well-known (but, indeed, often more expensive) manufacturer that produces a broad spectrum of drugs. Even if the health insurance carrier receives a rebate amounting to 30% to 40% of the manufacturer’s list price, there may still be, under some circumstances, even less expensive alternatives on the market, for which the insurer’s net expense is less even after deduction of the rebated amount (14, 15). Paradoxical as it may seem, it may be cheaper for the health insurance carrier when an inexpensive, non-rebated generic drug is prescribed with the specification “no substitution,” rather than a high-priced, but rebated drug. The SHI physician, however, is scarcely able to determine whether this is the case when prescribing the medication, because the health insurance carriers do not make the rebate conditions public. On the other hand, the SHI physician can make use of this option in situations where a rebated drug for an insuree would be subject to an obligatory supplementary payment because of reference price regulations, while a cheaper generic drug would not (16).

Prescription of an expensive generic drug not covered by a rebate contract, or of an originator drug not covered by a patent, with the specification “no substitution”

In this constellation as well, the determination of the preparation to be dispensed remains in the physician’s hands, but prescriptions of this type are generally considered uneconomical when cheaper drugs of equal medicinal value are available.

Overall, rebate contracts represent an additional type of intervention in the already highly regulated area of drug dispensing (17). The reported savings resulting from rebate contracts, in the amount of approximately 310 million euros for the entire SHI system in the year 2007 (18), represent only about 1.1% of total drug expenses, so it is clear that the economic benefit is limited. To be consistent, savings that would have been achieved through the “old” regulation on “no substitution” prescriptions ought to be deducted from this amount. The need for a comprehensive and publicly available assessment becomes clear when one takes the following additional factors into account:

the increasing lack of transparency of the market due to rebate contracts whose details are not available to the public

the resulting administrative expenses (notification, controlling, billing, etc.)

the near-total loss of cost consciousness among SHI physicians

the highly limited notion of cost-efficiency that takes nothing but drug prices into account

competitive effects, e.g., on the reference price system

legal uncertainties.

The present situation can be no more than a transitional phase. In 2005 and 2007, the Advisory Council on the Assessment of Developments in the Health Care System (Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der Entwicklung im Gesundheitswesen) proposed insurer-specific drug lists as an alternative regulatory mechanism that would be publicly communicated while remaining oriented toward market competition (19, 20). Perhaps this is a way to establish a dependable and stable regulatory framework for the provision of medications to the public.

Conclusion

Physicians and pharmacists are confronted by the task of getting accustomed to the current regulatory conditions and working together to make responsible use, not just of the “new” rebate contracts, but also of the “old” option of specifying “no substitution.” All parties involved urgently need a stable regulatory framework and a better, more open information policy. The effects of rebate contracts must be evaluated, so that not only their positive effects, but also their negative ones can be identified. As long as the regulations lack transparency, an adequate evaluation will remain practically impossible. In this area, there is an urgent, unmet need for health policy evaluation—something that Germany, up to the present, has seen very little of.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Claudia Kretschmer and Daniela Stahn of the GEK in Bremen for sorting the prescriptions.

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they are participating in third-party-sponsored projects of several different health insurance carriers. Mr. Pfannkuche is currently employed by Boehringer Ingelheim; this article was written while he was still working at the University of Bremen.

This study was performed without external financial support.

References

- 1.progenerika: Der Arzneimittelmarkt der gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung im Jahr 2008. Available at: www.progenerika.de/downloads/6387/090130_KurzanalyseDez.pdf. 2009 (last accessed: 26.05.2009) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfannkuche MS, Hoffmann F, Glaeske G. Rabattverträge für Arzneimittel. Noch mehr Intransparenz im Pharmamarkt? DAZ. 2007;147:2508–2512. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Müller CH. Ärzte dürfen nicht länger haften. Dtsch Arztebl. 2008;105(31-32):A 1646–A 1647. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giesecke S. Noch mehr Chaos. Dtsch Arztebl. 2008;105(7):A 312–A 313. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffmann F, Glaeske G, Pfannkuche MS. Korrekte Erfassung von Arzneimittelroutinedaten bei Betäubungsmittelrezepten und Muster 16 im Jahr 2006. GMS Med Inform Biom Epidemiol. 2008;4 Doc07. [Google Scholar]

- 6.IMS Health. Bei Arzneimitteln unter Rabattvertrag erlauben Ärzte häufiger Austausch durch Apotheker als bei „unrabattierten“ Medikamenten. www.imshealth.de/de/artikel/id/14021. 2008 (last -accessed: 26.05.2009) [Google Scholar]

- 7.KV Saarland. KVS-AKTUELL 3/2008 vom 06.08.2008. Available at: www.kvsaarland.de/dante-cms/app_data/adam/repo/5877_rundschreiben_03_2008.pdf. (last accessed: 26.05.2009) [Google Scholar]

- 8.KV Sachsen. KVS-Mitteilungen Heft 7-8/2007. Available at: www.kvs-sachsen.de/uploads/media/vahhm_06.pdf. (last accessed: 26.05.2009) [Google Scholar]

- 9.INSIGHT Health. INSIGHTs Einblicke, Ausgabe 04/2008. Available at: www.insight-health.de/publikationen/presse/newsletter_20080806.pdf. 2008 (last accessed: 26.05.2009) [Google Scholar]

- 10.NN. Das Nein zum Austausch variiert je nach Region. Ärztezeitung. 2007 06.12.2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann F, Pfannkuche MS, Glaeske G. Validität forschungsrelevanter Informationen in Arzneimittelroutinedaten über die Jahre 2000 bis 2006. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;133:945–949. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1075671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DocCheck 3D-Studie. DocCheck Online Studie Rabattverträge und Präparatesubstitution. http://research.doccheck.com/uploads/tx_dcevents/Rabattvertraege_3D_Links_mediaplayer.pdf. 2008 (last accessed: 26.05.2009) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neye H. Rabatt- und Risk-Share-Verträge in der Auswirkung auf das Verordnungsverhalten der Ärzte. Vortrag im Rahmen der 4. focus Veranstaltung; Düsseldorf. www.kvno.de/importiert/focus/neye_20080528_focus.pdf. 2008 (last accessed: 26.05.2009) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Häussler B, Höer A, Hempel E, Storz P. Der Arzneimittelverbrauch in der GKV. München: Urban & Vogel; 2008. Arzneimittel-Atlas 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfannkuche MS, Hoffmann F, Glaeske G. Wirtschaftlichkeitsreserven im Zeitalter von Rabattverträgen. In: Glaeske G, Schicktanz C, Janhsen K, editors. GEK-Arzneimittelreport. St. Augustin: Asgard-Verlag; 2008. pp. 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 16.NN. Rabattverträge. Teure Präparate und Zuzahlungszwang für Patienten. arznei-telegramm. 2008;39:76–77. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassel D. GKV-Arzneimittelversorgung in der Regulierungsfalle. Med Klin. 2008;103:260–263. doi: 10.1007/s00063-008-1037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rücker D. Rabattverträge: Einsparungen unter Zielpreisniveau. Pharmazeutische Zeitung. 2008;153 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der Entwicklung im Gesundheitswesen: Koordination und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen -(Gutachten 2005) 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der Entwicklung im Gesundheitswesen: Kooperation und Verantwortung. Voraussetzungen einer zielorientierten Gesundheitsversorgung (Gutachten 2007) 2007 [Google Scholar]