Abstract

Gemcitabine is a chemotherapy agent that may cause unpredictable side effects. In this report, we describe a fatal gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity in a patient with gallbladder metastatic adenocarcinoma. A 72-year-old patient was submitted to an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and a tubular adenocarcinoma in the gallbladder was incidentally diagnosed. CT scan and ultrasound before the surgery did not show any tumor. After the surgery a Pet scan was positive for a hot-spot in the left colon. The colonic lesion was conveniently removed and the histology evaluation confirmed the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma tubular. The patient was then submitted to three sections of 1,600 mg/m2 of gemcitabine with intervals of 1 week. Three weeks later he developed severe respiratory distress. A helicoidal CT scan showed diffuse and severe interstitial pneumonitis, and lung biopsy confirmed accelerated usual interstitial pneumonia consistent with drug-induced toxicity. The patient presented unfavorable evolution with progressive worsening of respiratory function, hypotension, and renal failure. He died 1 month later in spite of methylprednisolone pulse therapy, large spectrum antimicrobial therapy, and full support of respiratory, hemodynamic and renal systems. Gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity is usually a dramatic condition. Physicians should suspect pulmonary toxicity in patients with respiratory distress after gemcitabine chemotherapy, mainly in elderly patients.

Keywords: Chemotherapy toxicity, Gemcitabine, Pneumonitis, Gallbladder metastasis, Colon cancer

Introduction

Gemcitabine is a chemotherapy agent frequently elected to treat solid tumors, including breast, colonic, ovarian, pancreatic, and non-small cell lung cancers [1–12]. Its side effect is unpredictable and lung toxicity has been observed [1–13]. Metastatic gallbladder cancer is a complex and uncommon event [14–17]. In this report, we describe a case of gallbladder metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma associated with fatal gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity and discuss the histologic appearance of this dysfunction.

Case report

A 72-year-old male patient experienced an incidental diagnostic of tubular adenocarcinoma inside the gallbladder after elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy for chronic cholecystitis. CT scan and ultrasonographic evaluations performed before surgery were negative. Four days after cholecystectomy, he was submitted to laparotomy aiming radical resection; however, peritoneal carcinomatosis was observed. The patient was submitted to a tumor screening and a Pet scan pointed out a hot-spot in the left colon. This lesion was removed by colonoscopy and a histological examination confirmed a margin-free resection of a tubular adenocarcinoma. The patient was finally scheduled to receive three sections of gemcitabine (1,600 mg/m2) once a week. Three weeks after the completion of chemotherapy, he developed an important respiratory distress requiring ventilator support. A helicoidal CT scan showed bilateral and diffuse lung infiltrates (Fig. 1). A surgical lung biopsy was done and an accelerated usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) (Fig. 2), consistent with drug-induced toxicity, was observed. The patient presented with progressive impairment of respiratory function, coagulopathy, hypotension, and acute renal failure despite the use of methylprednisolone pulse therapy, large spectrum antimicrobial therapy, and full respiratory, hemodynamic and dialytic support. He died 1 month later. To assess the probability that the event was caused by gemcitabine we computed a Naranjo et al. [18] average point score, which is based on the direction of causality between the drug and the manifestation of adverse effects. Naranjo’s method estimates gemcitabine as the probable cause of pulmonary toxicity in the current report.

Fig. 1.

a Coronal reformatted images demonstrate involvement of all lung zones and predominantly upper lobe distribution of the ground-glass opacities and areas of consolidation. Also noted are reticulation and small cysts in the subpleural and basal regions of the lungs. b High-resolution CT image at the level of the main bronchi shows extensive bilateral ground-glass opacities and dependent areas of consolidation. Some emphysema can also be seen

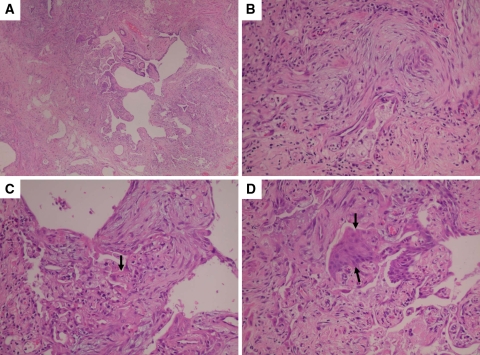

Fig. 2.

Lung surgical biopsy specimen showing accelerated usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). A characteristic area of honeycomb change is shown at low magnification (a). At lower left corner (a), the adjacent alveolar septa are homogeneously thickened by fibroblast and chronic inflammation. Higher magnification of area showed in lower left corner (b, c) highlights the fibroblasts and chronic inflammation within alveolar septa and shows associated hyaline membranes (arrow). The appearance coincides with the organizing stage of DAD. Note also the squamous metaplasia (arrows) of bronchiolar epithelium from adjacent honeycomb area (d). This finding is another sign of superimposed acute lung injury

Comments

There are several papers reporting pulmonary toxicity due to gemcitabine used as a single agent [1–8] or in combination with other antineoplastic agents [9–13]. The treatment of this event includes early use of steroid therapy administered either as pulses or continuously [1], mainly using methylprednisolone; nevertheless, most cases have a dramatic and fatal evolution. Our patient obtained fatal evolution in spite of the use of steroids as recommended in the literature.

Belknap et al. [3], reviewed data from spontaneous reports to Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports of pharmacovigilance (RADAR) program and appraised the clinical feature of gemcitabine-associated severe acute lung injury. Among 178 reports of gemcitabine-induced pulmonary injury (55 from clinical trials and 92 from spontaneous reports) dyspnea, fever, and pulmonary infiltrate were the most frequent symptoms of gemcitabine-induced pulmonary injury [3]. The median time to the diagnosis of this toxicity is 48 days (range 1–529) after initiation of gemcitabine.

Taxanes, docetaxel, and paclitaxel were the most frequent co-administered chemotherapies [3]. Eleven phase II or phase III clinical trials enrolling 317 patients identified pulmonary injury rates greater than 10% [3]. Highest rates of this toxicity (22 and 42%) were observed in phase III clinical trials in which patients with Hodgkin’s disease were treated with gemcitabine and bleomycin [3].

The authors concluded that high rates of gemcitabine-associated severe lung injury were observed, mainly when gemcitabine was combined with other agents that can also cause lung injury [3]. Just recently, Arrieta et al. [13], observed that radiotherapy and gemcitabine for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer is associated with excessive pulmonary toxicity.

Differently, Czarnecki and Voss [12] reviewed records of patients with pulmonary toxicity at FDA freedom of information (FDA-FOI) database and observed that there was no substantial difference in pulmonary toxicity with the combination of gemcitabine and taxanes in comparison with gemcitabine alone. Indeed, gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity is a dramatic condition. In the current case, the patient presented with rapidly progressive respiratory failure and the lung biopsy showed an accelerated UIP complicated by superimposed acute lung injury. Most reported cases have occurred in patients with known UIP, but the lesion can occur in patients with clinically unrecognized UIP [18]. The etiology of acute lung injury in UIP is unknown, but most cases are assumed to represent an inherent part of the natural history of UIP. Histologically, however, the changes cannot be separated from other causes of acute lung injury (such as viral infections, aspiration, sepsis, drug reactions, or toxic inhalants), and it is entirely possible that some cases may represent reactions to clinically unrecognized extrinsic lung insults [19]. Pathologically, the diagnosis is not usually difficult if all microscopic changes are taken into consideration. Classically, there are easily recognizable areas of UIP with patchwork pattern and honeycomb change. Focus of diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) recognizable by larger and more confluent interstitial fibroblast proliferation smaller than fibroblast foci of UIP are usually present [19]. Hyaline membranes are also present and they make easy diagnosis. Other findings of the diagnosis include squamous metaplasia in bronchiolar epithelium lining honeycomb areas. In the current case, Naranjo’s method identified gemcitabine as the probable agent of pulmonary toxicity.

The liver is the most common site of metastatic dissemination of a colonic tumor; however, a tumor from this region is very rare. In fact, this is the first report of metastasize inside the gallbladder from a tumor of colon origin. There are few reports describing gallbladder metastasize from other origins [13–16]. The prognostic of these patients was very poor with most of them achieving <1-year survival.

In summary, physicians should suspect pulmonary toxicity in patients with respiratory distress after gemcitabine chemotherapy, mainly in elderly patients that received high doses of this drug.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Rodrigo Caruso Chate, Service of Radiology of Albert Einstein Hospital of Sao Paulo, for his photo assistance and comments on images of the patients’ lungs and Lisa Ann Zelen for her English assistance.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Ash-Bernal R, Browner I, Erlich R. Early detection and successful treatment of drug-induced pneumonitis with corticosteroids. Cancer Invest. 2002;20:876–879. doi: 10.1081/CNV-120005899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ko E, Lee S, Goodman A. Gemcitabine pulmonary toxicity in ovarian cancer. Oncologist. 2008;13:807–811. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belknap SM, Kuzel TM, Yarnold PR, Slimack N, Lyons EA, Raisch DW, Bennett CL. Clinical features and correlates of gemcitabine-associated lung injury: findings from the RADAR project. Cancer. 2006;106:2051–2057. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho Kim D, Shiozawa S, Tsuchiya A, Usui T, Inose S, Aizawa M, Yoshimatsu K, Katsube T, Naritaka Y, Ogawa K. A case of drug-induced interstitial pneumonitis after adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine for pancreatic cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2008;35:133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pavlakis N, Bell DR, Millward MJ, Levi JA. Fatal pulmonary toxicity resulting from treatment with gemcitabine. Cancer. 1997;80:286–291. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19970715)80:2<286::AID-CNCR17>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manouras A, Lagoudianakis EE, Genetzakis M, Pararas N, Papadima A, Kekis PB. Metastatic breast carcinoma initially presenting as acute cholecystitis: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2008;l29:179–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaib W, Lansigan F, Cornfeld D, Syrigos K, Saif MW. Gemcitabine-induced pulmonary toxicity during adjuvant therapy in a patient with pancreatic cancer. JOP. 2008;9:708–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vahid B, Marik PE. Pulmonary complications of novel antineoplastic agents for solid tumors. Chest. 2008;133:528–538. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esteban E, Villanueva N, Muñiz I, Fernández Y, Fra J, Luque M, Jiménez P, Llorente B, Capelan M, Vieitez JM, Estrada E, Buesa JM, Jiménez-Lacave A. Pulmonary toxicity in patients treated with gemcitabine plus vinorelbine or docetaxel for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: outcome data on a randomized phase II study. Invest New Drugs. 2008;26:67–74. doi: 10.1007/s10637-007-9073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boeck S, Hausmann A, Reibke R, Schulz C, Heinemann V. Severe lung and skin toxicity during treatment with gemcitabine and erlotinib for metastatic pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2007;18:1109–1111. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3281ceabec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackstock AW, Ho C, Butler J, Fletcher-Steede J, Case LD, Hinson W, Miller AA. Phase Ia/Ib chemo-radiation trial of gemcitabine and dose-escalated thoracic radiation in patients with stage III A/B non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:434–440. doi: 10.1097/01243894-200606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czarnecki A, Voss S. Pulmonary toxicity in patients treated with gemcitabine and a combination of gemcitabine and a taxane: investigation of a signal using postmarketing data. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1759–1760. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arrieta O, Gallardo-Rincón D, Villarreal-Garza C, Michel RM, Astorga-Ramos AM, Martínez-Barrera L, de la Garza J. High frequency of radiation pneumonitis in patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with concurrent radiotherapy and gemcitabine after induction with gemcitabine and carboplatin. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:845–852. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a97e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manouras A, Lagoudianakis EE, Genetzakis M, Pararas N, Papadima A, Kekis PB. Metastatic breast carcinoma initially presenting as acute cholecystitis: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2008;29:179–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyle E, Nzewi E, Khan I, Al-Akash M, Crotty P, Neary PC. Small cell cervical cancer: an unusual finding at cholecystectomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279:251–254. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sand M, Bechara FG, Kopp J, Krins N, Behringer D, Mann B. Gallbladder metastasis from renal cell carcinoma mimicking acute cholecystitis. B Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:90–92. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-14-2-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langley RG, Bailey EM, Sober AJ. Acute cholecystitis from metastatic melanoma to the gall-bladder in a patient with a low-risk melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:279–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb14915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, Janecek E, Domecq C, Greenblatt DJ. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–245. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katzeinstein AL, Mukhopadhyay S, Myers JL. Diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia and distinction from other fibrosin interstitial lung diseases. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1275–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]