Abstract

The purpose of this study was to develop a framework for reporting health service models for managing rheumatoid arthritis (RA). We conducted a search of the health sciences literature for primary studies that described interventions which aimed to improve the implementation of health services in adults with RA. Thereafter, a nominal group consensus process was used to synthesize the evidence for the development of the reporting framework. Of the 2,033 citations screened, 68 primary studies were included which described 93 health service models for RA. The origin and meaning of the labels given to these health service delivery models varied widely and, in general, the reporting of their components lacked detail or was absent. The six dimensions underlying the framework for reporting RA health service delivery models are: (1) Why was it founded? (2) Who was involved? (3) What were the roles of those participating? (4) When were the services provided? (5) Where were the services provided/received? (6) How were the services/interventions accessed and implemented, how long was the intervention, how did individuals involved communicate, and how was the model supported/sustained? The proposed framework has the potential to facilitate knowledge exchange among clinicians, researchers, and decision makers in the area of health service delivery. Future work includes the validation of the framework with national and international stakeholders such as clinicians, health care administrators, and health services researchers.

Keywords: Classification, Health services, Information dissemination, Models of care, Reporting framework, Rheumatoid arthritis

Introduction

In the last decade, treatment strategies for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have evolved from the old “pyramid” approach to the early, proactive, and consistent use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) [1–6]. To minimize the delays in diagnosis, treatment initiation, and monitoring, a number of health service models, including the use of both pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment modalities, have been subsequently developed and evaluated [7].

A health service model may be labeled according to the setting in which the treatment modalities are implemented (e.g., inpatient team [8]), the leadership (e.g., the clinical nurse specialist model [9] and the physical therapist practitioner model [10]), or the mode of delivery (e.g., telehealth [11]). However, many labels have multiple meanings, which create communication challenges among health care professionals, researchers, and other decision makers. For example, models involving the use of communication equipment are commonly called “telehealth” and yet this term may refer to models with different modes of delivery including rheumatologist consultation provided through videoconferencing with the patient at the family physician’s office [11–13], through Internet and e-mails [14], or through telephone follow-up [15]. In addition, the lack of relevant detail regarding the health services model such as the objective(s) of the model, provider(s) of the service, and process of service delivery creates additional barriers when making decisions about patient care or implementing specific health service models into clinical practice.

Current standards for reporting clinical trials [16], including the most recent recommendations on the reporting of nonpharmacological interventions [17], focus on the inclusion of items that convey information about the study design, analysis, results, and interpretations of the findings. However, they provide little detail on how to systematically describe the features of complex health service interventions. This information would provide the reader with the ability to make informed judgments regarding the suitability of the model for their own patient population and to implement it in their practice setting.

The purpose of this study was to develop a reporting framework for health service models in RA care. To begin, we summarized how health service models in RA management were described through a systematic review of primary studies. We focused on RA instead of other types of arthritis because most health service models were developed for this population [7]. The essential components for reporting health service models were then identified and used to develop a framework for research reporting. We envision that this framework will facilitate knowledge exchange between researchers and research users.

Materials and methods

The research team consisted of individuals with expertise in clinical epidemiology (SO, LL, and TVV), research on nonpharmacological interventions in rheumatology (LL and TVV), and qualitative research (JK). In addition, one member was a health care administrator (CL) and one was a full-time physical therapist (HF). We conducted a search of the health sciences literature from 1990 to December 2005 in CINAHL, the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Healthstar, Medline, PEDro, PsycINFO, and Social Work Abstracts. The search strategy was developed in Medline by an experienced librarian in collaboration with the research team and modified as required for the other databases (Appendix A). To ensure that the literature search and review strategy were comprehensive, we sought input via online discussions with health service researchers, clinicians, health care administrators, and patient representatives who participated in the 2005 CARE III Conference [18].

Eligibility criteria and article selection

Primary studies that evaluated a health service delivery model for managing RA, published in either English or French, were included in this review. We defined a health service delivery model for the management of RA as an approach to delivering health services/interventions which may include services provided by nonhealth care professionals and/or health care professionals to adults with RA across the disease continuum. Examples include multidisciplinary team care, use of allied health professionals in advanced practice roles, telemedicine, patient-initiated care, and targeted care (e.g., foot or hand outpatient program). Studies involving a single treatment (e.g., a surgical procedure, a medication, or a physical therapy intervention) or a study population without RA, review articles, and editorials were excluded. Two team members (HF and SO) applied the eligibility criteria on the first 100 titles from the literature search and achieved good agreement (kappa = 0.71).

The selection of articles involved a two-step process. First, two of three team members (CL, HF, and SO) independently evaluated all retrieved studies using the bibliographic record (i.e., title, authors, keywords, abstract). Potentially relevant records or those that did not contain sufficient information to determine eligibility received a review of the full article from two of the same three members. Disagreements were resolved by consensus and reasons for exclusion were noted.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed by the research team to extract the components of health services from the literature. These components were based on our collective knowledge and experience on health service models in RA management. The data extraction form was pilot tested by the team using a randomly selected set of five eligible papers until consensus was reached and no further modifications were required. All team members participated in the review, with the information extracted by a primary reviewer and verified by a second reviewer. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Data extracted included the name of the model, setting, health professionals involved, modes and frequency of communication among health professionals, coordinator of the health services, initiator of the referral, the process of health service delivery, intervention(s) provided/received, frequency of health professional visits, length of the intervention, level of care provided (e.g., community, primary, secondary, or tertiary care) [19] and stage of disease according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for progression [20].

Development of reporting framework

Findings from the systematic review were used to inform the development of the reporting framework. The components that the team deemed important when describing the features of health service interventions for RA management (e.g., setting, health care professional(s) involved, etc.) were retained and expanded upon for the framework.

The framework was comprised of six fundamental dimensions relating to health service delivery models: Why?, Who?, What?, When?, Where?, and How? Within the “How?” dimension, multiple questions were addressed. Information under each question were classified as a component (i.e., mutually exclusive categories consisting of information that were vital to describing a health service model) or subcomponent (i.e., optional information). The research team, using a nominal group approach, carried out this process through independent reflection as well as five face-to-face meetings, with one team member that had experience with this approach (JK) attending as a facilitator [21]. Additional literature nominated by the team were used to facilitate the selection of components and subcomponents [7, 22, 23].

The nominal group process began with a discussion on the components of health service delivery models to include from the literature review in the reporting framework. Next, the team developed an overall structure for the reporting framework. This was followed by independent reflection on how best to classify the information into components and subcomponents as previously defined. Responses were collated and consensus was sought during the five facilitated face-to-face meetings. The document was then revised by JK and reviewed by the team for final editing.

Results

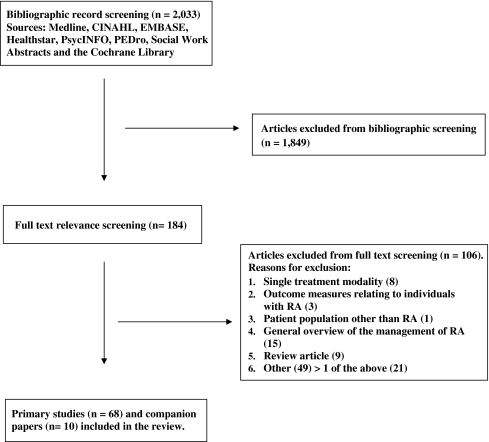

Of the 2,033 citations retrieved and screened, 78 papers (68 primary studies [91% in English] and ten companion papers) met the eligibility criteria (Fig. 1) and 93 descriptions of health service models were identified (Appendix B). While the vast majority of models (95.7%) reported the health professionals involved, the mode and frequency of communications between health professionals and patients were only described in 43.0% and 36.6% of the models, respectively (Table 1). The majority of models also reported the setting where services were provided (89.2%), the level of care (89.2%), and the coordinator of the overall health service delivery (61.3%). Around half of the models described the length of the intervention (59.1%), the initiator of the referral (54.8%), the services provided to and received by patients (53.8%), and the disease duration (51.6%). However, less than one third reported the frequency of health professional visits, only 8.6% stated the ACR classification of global functioning of the study participants, and none of the models reported the stage of disease according to the ACR criteria for progression.

Fig. 1.

Literature search strategy

Table 1.

Attributes of health service delivery models for the management of RA reported in the literature

| Attribute | Frequency of reporting (n = 93), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Health professionals involved | 89 (95.7) |

| Setting where the services were provided | 83 (89.2) |

| Level of care | 83 (89.2) |

| Coordinator of overall health service delivery | 57 (61.3) |

| Length of the service | 55 (59.1) |

| Initiator of the referral | 51 (54.8) |

| Service delivery process | 51 (54.8) |

| Services provided/received | 50 (53.8) |

| Disease duration | 48 (51.6) |

| Mode of communication among health professionals | 40 (43.0) |

| Frequency of communication among health professionals | 34 (36.6) |

| Frequency of the provision of services/health care professional visits | 28 (30.1) |

| ACR classification of global functioning | 8 (8.6) |

| Stage of disease according to the ACR criteria for progression | 0 (0.0) |

Included studies: 68 primary studies and ten companion papers reporting on 93 health service delivery models for the management of RA (see Appendix B)

Reporting framework for health service models

To synthesize the information from the literature review on the components deemed important when describing health services interventions for RA management, the six questions about health service models were further modified as follows:

Why was the health service delivery model founded?

Who was involved?

What were the roles of the individuals participating?

When were the health services/interventions provided and/or received?

Where were the health services/interventions provided and/or received?

How were the services/interventions accessed? How are the services/interventions implemented? How long was the intervention? How did the individuals involved communicate? How was the health service delivery model supported and sustained?

The nominal group process indentified and defined were components and subcomponents for each set of questions (Table 2). To illustrate the application of the reporting framework, examples are provided using five papers on health service models published between 2006 and 2007 (Table 3) [24–28].

Table 2.

Framework for reporting health service delivery models for managing rheumatoid arthritis

| Dimension | Component | Subcomponent |

|---|---|---|

| Why? | ||

| Why was the health service delivery model founded? | Goals of the model | Goals related to patient outcome(s); goals related to the intervention |

| Who? | ||

| Who was involved? | Provider(s) | Health care professional(s); nonhealth care professional(s) |

| User(s) | ||

| What? | ||

| What were the roles of the individuals involved? | Role of provider(s) | |

| Role of user(s) | ||

| When? | ||

| When were the health services/interventions provided and/or received? | Duration of disease since onset of symptoms and/or diagnosis | |

| Where? | ||

| Where were the health services/interventions provided and/or received? | Setting | |

| Country | ||

| Level of care: community; primary care; secondary care; follow-up; orthopedic surgical consultation; preorthopedic and postorthopedic surgery | ||

| How? | ||

| How did patients access the service(s)/interventions(s)? | Referral process | |

| How were the services/interventions implemented? | Method(s) in which the interventions are delivered | |

| How long was the intervention? | Duration of the intervention | |

| How did individuals involved communicate? | Mode(s) of communication | Among providers; between user(s) and provider(s) |

| How was the health service delivery model supported/sustained? | Resources needed to support or sustain the model | Financial; human |

Table 3.

Application of the reporting framework for health service delivery models in the management of RA using primary studies from the literature

| Dimension | Component | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Why? | Goals of the model | “The aim of the service was to improve care pathways for patients and reduce waiting times for secondary care rheumatology patients.” (25) |

| Who? | Provider(s) of care | “The multidisciplinary team included a nurse, an occupational therapist, a physiotherapist, a social worker and a consultant rheumatologist,…” (27) |

| User(s) of care | “…all patients with early polyarthritis, aged 18–60 years, referred to the Department of Rheumatology at Karolinska University Hospital…” (27) | |

| What? | Role of provider(s) | “The team nurse acted as co-coordinator between the patient, other team members, the employer and the official in charge from the social insurance office. The occupational therapist examined the need of technical aids at home and at work…The physiotherapist instructed the patient on how to maintain mobility and increase physical strength…The social worker…contacted employers and social security officials…The rheumatologist managed the pharmacological therapy and was responsible for all evaluations…” (27) |

| Role of user(s) | “Patients were given self-referral of symptoms (SOS) appointments, rather than a routine follow-up appointment…Patients were given a slip of paper with a secretary’s direct telephone number… If the secretary was unavailable, they were asked to use the patients’ telephone helpline and state that they required an SOS appointment because their symptoms (e.g. joint swelling) were now present.” (27) | |

| When? | Duration of disease | “DMARD-naïve patients with recent-onset (<2 years), clinically active RA fulfilling the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria were eligible.” (24) |

| Where? | Country and setting | “This study was conducted in five university hospitals, the Rheumatism Foundation Hospital, and 12 central hospital rheumatology practices serving the entire population of each area and most parts of Finland.” (24) |

| Level of care | “The rheumatology department at The Royal Oldham Hospital developed a primary care service aimed at bridging the gap between primary and secondary care for patients with potential rheumatological conditions, and this was given the name rheumatology tier 2.” (25) | |

| How? | Referral process | “With few exceptions, all patients with recent-onset RA in Finland are referred to hospital outpatient clinics for assessment because consulting with a specialist is a prerequisite for a claim for drug reimbursement according to national legislation.” (24) |

| Method(s) by which the services interventions were implemented | “…patient centred approach…” (25) | |

| Duration of the intervention(s) | “Each patient attends the nurse-led clinic for 30 min, seeing the same nurse one to three times per year depending on the individual’s need.” (26) | |

| Modes of communication | “The team met all patients every third month during the first year and every sixth month in the second year. If needed, additional visits to any team member could be offered…Meetings for planning the work rehabilitation were arranged whenever needed and included participation by the patient, the team, the local social insurance officer and/or the employer.” (27) | |

| Resources to support/sustain the model | “In Finland, the Social Insurance Institution (SII) is, under law, required to assess an individual’s need for rehabilitation when he or she is or has been on sick leave and has received sickness allowance for 60 days, and again at 150 days. Patients can be awarded inpatient rehabilitation to improve their functional and work capacity, or they are entitled to vocational rehabilitation.” (24) |

The “Why” question addresses the model’s goals, which may include improving patient outcomes (e.g., reducing pain, reducing work disability, improving quality of life, etc.) or improving the process of service delivery (e.g., reducing delay for diagnosis, improving the coordination of the health service delivery, minimizing duplication of services, or reducing healthcare costs).

The “Who” question focuses on the reporting of the providers and users of the health service. Providers may include health care professionals (e.g., registered nurses, primary care physicians, specialists, and allied health professionals) and/or nonhealth care professionals (e.g., informal caregivers, healthcare administrators, and job counselors). User of health services may include the patient and patient’s family and/or friends.

The “What” question addresses the roles of the provider(s) and user(s) involved in the health service delivery model. Providers’ roles may include being the champion for the model, providing a specific service (e.g., screening, triaging cases, providing education), or coordinating the overall delivery of the health services. For users of health services, roles may include initiating a clinical visit, participating in treatment goal setting, or practicing self-management techniques.

The “When” question addresses the reporting of the disease duration, i.e., time from onset of symptoms and/or diagnosis.

The “Where” question focuses on to the location where the health services were provided or received. The components include the country of origin, the setting (e.g., inpatient hospital program, outpatient hospital program, community clinic, patient’s home, etc.) and the level of care. The potential categories for levels of care that authors can use include the following: community care, primary care, secondary care, follow-up, orthopedic surgical consultation, or preorthopedic/postorthopedic surgery. Community care involves services and/or information received between the onset of the patient’s symptoms and their first visit to the family physician. Primary care includes services provided by the family physician and/or other primary care team members. Secondary care services are provided by rheumatologists or other specially trained health care professionals, such as rheumatology nurse practitioners. Follow-up services are typically provided to monitor disease activity and adverse events due to medications. An orthopedic consultation is provided by an orthopedic surgeon prior to the patient’s surgical intervention. Lastly, preorthopedic and postorthopedic surgery services are provided prior to and following the surgical intervention in order to prepare the patient for surgery and monitor their recovery and progress [7].

Lastly, the “How” question addresses five topics, including (1) the referral process, (2) the process through which the interventions are implemented, (3) the duration of the interventions, (4) the mode of communication of the individuals involved, and (5) resources for supporting and sustaining the health service model.

The referral process may include self-referral, referral from a health care professional/case manager, or recruitment via a research study. The methods in which the intervention can be implemented include the use of a care pathway or treatment guidelines, the provision of individualized care, and/or by simply following the study protocol. Information regarding how individuals communicate in the health service delivery model can be captured by a description of the modes of communication, for instance, team conferences, individual face-to-face meetings, telephone, e-mail, etc. Lastly, the resources used to support/sustain the health service delivery model are captured from a financial perspective (e.g., public and/or private funding) and a human perspective (e.g., champion or founder of the model of care).

Discussion

This review has found several trends in the reporting of health service delivery models in the management of RA within the peer-reviewed literature. Although the vast majority of models in RA management reported on the individuals involved in providing the service, the setting, and the level of care, only half provided information about the length of the intervention or the process of health service delivery. Results also showed shortcomings in the description about the patient population, with less than 10% having reported on the functional level and the stage of disease progression and only half reported on the disease duration. Overall, the quality of reporting the features of health service interventions in the management of RA is poor.

We argue that the discrepancies in reporting may have contributed to the slow progress in the development, implementation, and evaluation of effective models in RA management. The first study about the team care model was published more than 40 years ago [29]; since then, few articles and systematic reviews on health service delivery models for RA have been published [7, 30]. Some models, including team care and nurse-led clinics, have demonstrated effectiveness in improving patient outcomes. However, it remains a challenge to identify what makes a model work and how to implement an effective model in specific settings.

More than 15 years ago, Yelin pointed out that the active ingredients of team care could be the result of the formal elements such as the health professionals involved and their interaction at structured meetings, the informal elements such as how people communicate, or both [31]. This had led to the question, “What’s inside the team care box?” [31]. Researchers have been encourage to clearly define and test different components of team care and other models in order to identify what contributes to an effective model. But little has been changed in the reporting of health service models. Since Yelin published his editorial, health care professionals and other decision makers still experience difficulties in sorting out the elements that make a model work, the requirement for implementing a model locally, and the resources needed for sustaining a model. This issue, noted at the 2005 Summit on Standards for Arthritis Prevention and Care meeting, has contributed to the inability to propose a definite standard on health service delivery models for Canada [32].

From the experience of other initiatives that aim to improve research reporting, we anticipate that our reporting framework will help facilitate the development, implementation, and evaluation of health service models in the clinical setting. Prior to the mid-1990s, the quality of clinical trial reporting was poor [33] and this led to the development of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement to provide standards for research reporting [16, 17, 34, 35]. A recent extension of the CONSORT statement to randomized trials on nonpharmacological treatment provide guidelines on the reporting of participants (i.e., eligibility criteria for the centers and those performing the interventions), interventions (i.e., precise details of both the experimental treatment and comparator), and corresponding examples of good reporting. There is now increasing evidence that the CONSORT statement may have contributed to improve reporting in some fields [36–38]; however, it is not sufficient to serve as a standard for reporting all the attributes of a health service delivery intervention for the management of RA. Furthermore, although theoretical evaluation frameworks for programs or interventions are available, a majority of them are general frameworks and do not address specific aspects related to complex interventions in managing chronic diseases [39]. For example, while the UK Medical Research Council published a framework that outlines the appropriate methods to adopt when developing or evaluating complex interventions, the description of the intervention is not highlighted [40]. This stresses the need for a reporting framework that addresses the description of the health service delivery intervention itself.

The role of the patient is vital in the way a health care organization that provides services (versus tangible products) is managed and evaluated. For this reason, the inclusion of the patient’s role is a definite strength in the proposed reporting framework [41]. However, despite the rigorous process used to develop this framework, there are three limitations with regards to this study. First, there was no theoretical framework or reporting format for health service interventions available at the time we developed our data extraction form. Since, general health service research reporting paper has been published by Glasziou et al. which provides guidelines on how to describe nonpharmacological treatments in research studies and hence complements our reporting framework [42]. Second, the framework was developed using results from a systematic review of the literature and a nominal group technique involving six research team members; therefore, the components and subcomponents might not reflect all the relevant information needed by a decision maker when considering a health service model. Third, the included studies were published between 1990 and 2005. Although several articles on RA models were published after this time period, we believe that they have little effect on the general trend of our findings because, to our knowledge, there were no major advances in the reporting methodology in this field between 2005 and 2008.

In conclusion, there is room for improvement within the arthritis field in describing health service delivery models in the peer-reviewed literature. The proposed reporting framework offers a practical solution by providing guidance to researchers to prepare research reports. Further evaluation is required to ensure that the framework covers all relevant information from the perspectives of health care professionals and other decision makers, can be easily applied, and improves research reporting. The proposed framework has the potential to facilitate the improved reporting of health service interventions in other chronic conditions and we encourage its adoption and modification for the reporting of health service interventions in other fields.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Alexandra Davis, librarian scientist, for her contribution in the development, refinement, and execution of the literature search strategy. This project was supported by the Physiotherapy Foundation of Canada through the Alberta Research Award. Dr. Li is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award and an American College of Rheumatology Research and Education Foundation Health Professional New Investigator Award.

Disclosures

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Appendix A: Medline search strategy

exp Arthritis, Rheumatoid/

(rheumat$ adj2 arthritis).tw.

rheumatoid nodule$.tw.

(spondylitis adj2 (ankylosing or rheumatoid)).tw.

bechterew$ disease.tw.

marie stru#mpell.tw.

((caplan$ or felty$ or sjogren$) adj2 syndrome).tw.

still$ disease.tw.

or/1–8

models, nursing/

Nurse Clinicians/

clinical nurse specialist$.tw.

nurse practitioners/

(traditional adj2 model$).tw.

(nurse adj2 clinics).tw.

Community Health Nursing/ or community health centers/

(rehabilitation adj2 model$).tw.

rehabilitation/

occupational therapy/

“Physical Therapy (Specialty)”/

((physical therap$ or physiotherap$) adj2 practitioner$).tw.

(care adj2 model$).tw.

(practice adj2 model$).tw.

(medical adj2 model$).tw.

(practitioner adj2 model$).tw.

(primary therap$ adj2 model$).tw.

(rheumatolog$ adj2 primary therap$).tw.

triage/

((physical therap$ or physiotherap$ or occupational therap$) adj2 triage).tw.

disease management/

Patient Care Team/ or Patient-Centered Care/

((patient or client or consumer) adj (centered care or directed care)).tw.

Professional Practice/

patient care/

case management/

((multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary or allied health or multiprofessional or integrated) adj3 (team$ or care or approach)).tw.

((healthcare or health care) adj1 team$).tw.

day patient team$.tw.

ambulatory care facilities/ or outpatient clinics, hospital/

Ambulatory Care/

Primary Health Care/

primary care therap$.tw.

telemedicine/ or remote consultation/

(telehealth or telemedicine or teleconsultation or telerheum$).tw.

Hotlines/ or hotline$.tw.

home care services/ or home care services, hospital-based/ or home nursing/

(home care or home nursing).tw.

Self Care/

(self-care or self-management).tw.

health education/ or patient education/

((health or patient) adj1 education).tw.

Counseling/ or counseling.tw.

Self-Help Groups/

((self-help or support) adj1 group$).tw.

Patient Satisfaction/ or patient satisfaction.tw.

(patient adj1 preference$).tw.

Social Work/ or social worker$.tw.

PHARMACISTS/

PHARMACY/ or PHARMACY SERVICE, HOSPITAL/ or COMMUNITY PHARMACY SERVICES/

Dietetics/ or dietitian$.tw.

Allied Health Personnel/

Health Services Research/

“Delivery of Health Care, Integrated”/

Managed Care Programs/

og.fs.

or/10–66

9 and 67

limit 68 to humans

limit 69 to (english or french)

limit 70 to yr = “1990–2006”

limit 71 to (“review” or review, academic or “review literature”)

limit 71 to (comment or editorial)

limit 71 to congresses

limit 71 to (news or newspaper article)

limit 71 to (guideline or practice guideline)

or/72–76

71 not 77

limit 78 to (“all infant (birth to 23 months)” or “all child (0 to 18 years)”)

limit 78 to (“all adult (19 plus years)” or “all aged (65 and over)” or “aged (80 and over)”)

78 not 79

80 or 81

Appendix B

Table 4.

Included studies

| Study number | Number of models described | Label of model(s) | Primary study (companion papers) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Primary therapist model; traditional treatment model | Li L; Davis AM; Lineker SC; Coyte PC; Bombardier C. Effectiveness of the primary therapist model for rheumatoid arthritis rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2006, 55(1):42–52 |

| (Li L; Maetzel A; Davis AM; Lineker SC; Bombardier C; Coyte PC. Primary therapist model for patients referred for rheumatoid arthritis rehabilitation: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2006, 15; 55(3):402–410) | |||

| (Li L; Davis AM; Lineker SC; Coyte PC; Bombardier C. Outcomes of home-based rehabilitation provided by primary therapists for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: pilot study. Physiotherapy Canada 2005; 57:255–264) | |||

| 2 | 1 | Specialist rheumatology nursing practice | Minnock P. Intra-articular injections in specialist rheumatology nursing practice. All Ireland Journal of Nursing & Midwifery 2002; 4:32–35 |

| 3 | 1 | Not provided | Zink A; Listing J; Klindworth C; Zeidler H; German Collaborative Arthritis Centre. The national database of the German Collaborative Arthritis Centres: I. Structure, aims, and patients. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2001; 60(3):199–206 |

| 4 | 1 | Telephone helpline | Hughes RA; Carr ME; Huggett A; Thwaites CE. Review of the function of a telephone helpline in the treatment of outpatients with rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2002; 61(4):341–345 |

| 5 | 1 | Not provided | Gordon M; Thomson EA; Madhok R; Capell HA. Can intervention modify adverse lifestyle variables in a rheumatoid population? Results of a pilot study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2002; 61(1):66–69 |

| 6 | 1 | Multidisciplinary arthritis training program | Scholten C; Brodowicz T; Graninger W; Gardavsky I; Pils K; Pesau B; Eggl-Tyl E; Wanivenhaus A; Zielinski CC. Persistent functional and social benefit 5 years after a multidisciplinary arthritis training program. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 1999; 10:1282–1287 |

| 7 | 2 | Rheumatologist as primary care provider; rheumatologist provides specialty care only | Gabriel SE; Wagner JL; Zinsmeister AR; Scott CG; Luthra HS. Is rheumatoid arthritis care more costly when provided by rheumatologists compared with generalists? Arthritis & Rheumatism 2001; 7:1504–1514 |

| 8 | 1 | Transmural rheumatology nurse clinics | Temmink D; Hutten JBF; Francke AL; Rasker JJ; bu-Saad HH; van der ZJ. Rheumatology outpatient nurse clinics: a valuable addition? Arthritis & Rheumatism 2001; 3:280–286 |

| 9 | 3 | Clinical nurse specialist; inpatient team; day patient team | Tijhuis GJ; Zwinderman AH; Hazes JMW; van den Hout WB; Breedveld FC; Vliet Vlieland TPM. A randomized comparison of care provided by a clinical nurse specialist, an inpatient team, and a day patient team in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2002; 5:525–531 |

| (van den Hout WB; Tijhuis GJ; Hazes JM; Breedveld FC; Vliet Vlieland TP. Cost effectiveness and cost utility analysis of multidisciplinary care in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised comparison of clinical nurse specialist care, inpatient team care, and day patient team care. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2003; 62(4):308–315) | |||

| (Tijhuis GJ; Kooiman KG; Zwinderman AH; Hazes JMW; Breedveld FC; Vliet Vlieland TPM. Validation of a novel satisfaction questionnaire for patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving outpatient clinical nurse specialist care, inpatient care, or day patient team care Arthritis & Rheumatism 2003; 2:193–199) | |||

| (Tijhuis GJ; Zwinderman AH; Hazes JMW; Breedveld FC; Vlieland PMT. Two-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of a clinical nurse specialist intervention, inpatient, and day patient team care in rheumatoid arthritis Journal of Advanced Nursing 2003; 1:34–43) | |||

| 10 | 2 | Treatment counseling strategy; symptom monitoring | Maisiak R; Austin J; Heck L. Health outcomes of two telephone interventions for patients with rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism 1996; 39(8):1391–1399 |

| 11 | 1 | Gerontorheumatologic outpatient service | van LW; Franssen M; Van KM; van de PL. Gerontorheumatologic outpatient service. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2004; 51(2):299–301 |

| 12 | 2 | Job-retention vocational rehabilitation program; usual care | De Buck PDM; Le CS; van den Hout WB; Peeters AJ; Ronday HK; Westedt M; Breedveld FC; Vliet Vlieland TPM. Randomized comparison of a multidisciplinary job-retention vocational rehabilitation program with usual outpatient care in patients with chronic arthritis at risk for job loss. Arthritis Care & Research 2005; 3(5):682–690 |

| 13 | 2 | Clinic-based ambulatory care; home-based physiotherapy | Li PC; Coyte PC; Lineker SC; Wood H; Renahan M. Ambulatory care or home-based treatment? An economic evaluation of two physiotherapy delivery options for people with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care and Research 2000; 4:180–193 |

| 14 | 1 | Rheumatology monitoring clinics | Thompson PW; Moran CJ; Aubrey-Fletcher S. Rheumatology monitoring clinics. Baillieres Clinical Rheumatology 1992; 6(1):95–116 |

| 15 | 2 | Rheumatology nurse practitioner (RNP) clinic; consulting rheumatologist clinic | Hill J; Bird HA; Harmer R; Wright V; Lawton C. An evaluation of the effectiveness, safety and acceptability of a nurse practitioner in a rheumatology outpatient clinic. British Journal of Rheumatology 1994; 33(3):283–288 |

| (Hill J. Patient satisfaction in a nurse-led rheumatology clinic Journal of Advanced Nursing 1997; 2:347–354) | |||

| 16 | 2 | Day patient care; inpatient care | Lambert CM; Hurst NP; Lochhead A; McGregor K; Hunter M; Forbes J. A pilot study of the economic cost and clinical outcome of day patient vs inpatient management of active rheumatoid arthritis British Journal of Rheumatology 1994; 33(4):383–388 |

| (Lambert CM; Hurst NP; Forbes JF; Lochhead A; Macleod M; Nuki G. Is day care equivalent to inpatient care for active rheumatoid arthritis? Randomised controlled clinical and economic evaluation (structured abstract) British Medical Journal 1998; 316:965–969) | |||

| 17 | 2 | Inpatient multidisciplinary; routine outpatient care | Vliet Vlieland TPM; Zwinderman AH; Vandenbroucke JP; Breedveld FC; Hazes JMW. A randomized clinical trial of in-patient multidisciplinary treatment versus routine out-patient care in active rheumatoid arthritis. British Journal of Rheumatology 1996; 35(5)475–482 |

| (Vliet Vlieland TP; Breedveld FC; Hazes JM. The two-year follow-up of a randomized comparison of in-patient multidisciplinary team care and routine out-patient care for active rheumatoid arthritis British Journal of Rheumatology 1997; 36(1):82–85) | |||

| 18 | 1 | Outreach program | Toupin A; Denford-Nelson B. Arthritis Society outreach program: British Columbia and Yukon division. Canadian Journal of Rehabilitation 1993; 4:238–243 |

| 19 | 1 | Early arthritis clinic | Cush JJ. Early arthritis clinic: a USA perspective. Clinical & Experimental Rheumatology 2003; 21(5 Suppl 31):S75–S78 |

| 20 | 1 | Program for Rheumatic Independent Self-Management (PRISM) | Alderson M; Starr L; Gow S; Moreland J. The program for rheumatic independent self-management: a pilot evaluation. Clinical Rheumatology 1999; 18(4):283–292 |

| 21 | 1 | Community-oriented program | Ronen R; Braun Z; Eyal P; Eldar R. Rehabilitation in practice. A community-oriented programme for rehabilitation of persons with arthritis. Disability and Rehabilitation 1996; 9:476–481 |

| 22 | 1 | Advance Profiling of Anti-Rheumatic Therapies (APART) | [No authors listed] Using technology to improve patient–physician communication. Disease Management Advisor 2004; 10(1):1–4 |

| 23 | 2 | Intensive rehabilitation services; office-based care | Sinacore JM; Chang RW; Falconer J. Seeing the forest despite the trees. The benefit of exploratory data analysis to program evaluation research. Evaluation & the Health Professions 1992; 15(2):131–146 |

| 24 | 1 | General practice | Memel DS; Kirwan JR. General practitioners’ knowledge of functional and social factors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Health and Social Care in the Community 1999; 6:387–393 |

| 25 | 2 | Symptomatic care; aggressive care | Symmons D; Tricker K; Roberts C; Davies L; Dawes P; Scott DL. The British Rheumatoid Outcome Study Group (BROSG) randomised controlled trial to compare the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of aggressive versus symptomatic therapy in established rheumatoid arthritis. Health Technology Assessment 2005; 34:iii–iiv |

| 26 | 3 | Visiting clinic; e-mail consultation; video consultation | Jong M; Kraishi M. A comparative study on the utility of telehealth in the provision of rheumatology services to rural and northern communities. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 2004; 63(4):415–421 |

| 27 | 1 | Multidisciplinary team care | Verhoef J; Toussaint PJ; Putter H; Zwetsloot-Schonk JHM; Vliet Vlieland TPM. Pilot study of the development of a theory-based instrument to evaluate the communication process during multidisciplinary team conferences in rheumatology International Journal of Medical Informatics 2005; 74(10):783–790 |

| 28 | 1 | Multiprofessional rehabilitation team | Long AF; Kneafsey R; Ryan J. Rehabilitation practice: challenges to effective team working. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2003; 40(6):663–673 |

| 29 | 1 | Rehabilitation in Community (RIC) | Georgievski AB. Rehabilitation in the community. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 2000; (1):1–6 |

| 30 | 1 | Not provided | Wooten MD; Johnson RD. Factors affecting patient satisfaction with follow-up by a nurse practitioner in an outpatient rheumatology clinic. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology 2000; 6(4):184–188 |

| 31 | 1 | Health status reports | Kazis LE; Callahan LF; Meenan RF; Pincus T. Health status reports in the care of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 1990; 43(11):1243–1253 |

| 32 | 2 | Primary care; secondary care | Arthur V; Clifford C. Rheumatology: a study of patient satisfaction with follow-up monitoring care. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2004; 3:325–331 |

| 33 | 2 | Primary care; secondary care | Arthur V; Clifford C. Rheumatology: the expectations and preferences of patients for their follow-up monitoring care: a qualitative study to determine the dimensions of patient satisfaction. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2004; 2:234–242 |

| 34 | 1 | Dorothea Orem Model | Stewart M; Bassett P. Using models in practice. Journal of Community Nursing 1992; 6:16–20 |

| 35 | 1 | Primary care | Mikuls TR; O’Dell JR. Managing RA in the primary care setting: early diagnosis, disease-modifying agents, and comorbidities are key elements. Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine 2003; 1:12–14 |

| 36 | 1 | Team care | Pigg JS. Rheumatoid arthritis: how allied health professionals can help… seventh in a special series of articles on diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine 1995; 2:27–30 |

| 37 | 1 | Telehealth rheumatology consults | Davis P; Howard R; Brockway P. An evaluation of telehealth in the provision of rheumatologic consults to a remote area. Journal of Rheumatology 2001; 8:1910–1913 |

| 38 | 1 | Early arthritis clinic | Machold KP; Eberl G; Burkhard FL; Nell V; Windisch B; Smolen JS. Early arthritis therapy: Rationale and current approach. Journal of Rheumatology 1998; 25(Suppl 53):13–19 |

| 39 | 4 | Specialty care without primary care; specialty and primary care primary care without specialty care; neither primary care nor specialty care | MacLean CH; Louie R; Leake B; McCaffrey DF; Paulus HE; Brook RH; Shekelle PG. Quality of care for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of the American Medical Association 2000; 284(8):984–992 |

| 40 | 1 | Interdisciplinary/multidisciplinary holistic approach | McCain J; Hagan SJ. Managing chronic foot pain. A case report. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association 1990; 80(5):251–253 |

| 41 | 2 | Intensive outpatient management; routine outpatient care | Grigor C; Capell H; Stirling A; McMahon AD; Lock P; Vallance R; Kincaid W; Porter D. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 9430:263–269 |

| 42 | 1 | Drug prescribing by nurses | Hennell SL; Wood BB; Spark EW. Competency and the use of clinical management plans in rheumatology practice. Nurse Prescribing 2004; 1:26–30 |

| 43 | 1 | Specialist nurse | Ryan S. Defining the role of the specialist nurse. Nursing Standard 1996; 17:27–29 |

| 44 | 1 | Shared care | Ryan S. Sharing care in an outpatient clinic. Nursing Standard 1995; 6:23–25 |

| 45 | 1 | Community nurse | Ryan S. The rheumatology community nurse. Nursing Times 2001; 33:38 |

| 46 | 1 | Home-based self-treatment with cytotoxic drugs | Smy J. Helping patients to help themselves. Nursing Times 2004; 35:24–25 |

| 47 | 1 | The arthritis team/interdisciplinary care model | Zimm A. The arthritis team. On Call 1999; 10:18–21 |

| 48 | 1 | Nurse coordinator | Pigg JS. Case management of the patient with arthritis… implementing case management across the continuum: the transition of the orthopaedic patient… proceedings of selected papers from the NAON 1996 Fall Case Management Conference held in New Orleans, LA, November 14–16, 1996. Orthopaedic Nursing 1997 |

| 49 | 1 | Multidisciplinary team care | Siu AM; Chui DY. Evaluation of a community rehabilitation service for people with rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Education & Counseling 2004; 55(1):62–69 |

| 50 | 1 | Multidisciplinary team care | Kapoor MS. The rheumatology pharmacist is a team-player with diverse responsibilities. Pharmacy in Practice 2005; 15(6):230–232 |

| 51 | 1 | Practice-based arthritis clinic | Marchant C. Practice nurse of the year: arthritis aid… arthritis clinic. Practice Nurse 1995; 4:248 |

| 52 | 1 | Multidisciplinary team care | O’Donovan J. Clinical update. Managing rheumatoid arthritis: the role of nurses in a multidisciplinary team. Primary Health Care 2004; 4:30–32 |

| 53 | 1 | Nurse case management | Barry J; McQuade C; Livingstone T. Using nurse case management to promote self-efficacy in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Rehabilitation Nursing 1998; 6:300–304 |

| 54 | 1 | Multidisciplinary team care | Prier A; Berenbaum F; Karneff A; Molcard S; Beauvais C; Dumontier C; Sautet A; Miralles MP; Peroux JL; Kaplan G. Multidisciplinary day hospital treatment of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Evaluation after two years. Revue du Rhumatisme (English Edition) 1997; 64(7–9):443–450 |

| 55 | 1 | Specialist foot clinics | Helliwell PS. Lessons to be learned: review of a multidisciplinary foot clinic in rheumatology. Rheumatology 2003; 42(11):1426–1427 |

| 56 | 1 | Telephone helpline | McCabe C; McDowell J; Cushnaghan J; Butts S; Hewlett S; Stafford S; O’Hea J; Breslin A. Rheumatology telephone helplines: an activity analysis. South and West of England Rheumatology Consortium. Rheumatology 2000; 39(12):1390–1395 |

| 57 | 2 | Traditional, routine rheumatologist-initiated review; patient-initiated review | Hewlett S; Mitchell K; Haynes J; Paine T; Korendowych E; Kirwan JR. Patient-initiated hospital follow-up for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2000; 39(9):990–997 |

| (Kirwan JR; Mitchell K; Hewlett S; Hehir M; Pollock J; Memel D; Bennett B. Clinical and psychological outcome from a randomized controlled trial of patient-initiated direct-access hospital follow-up for rheumatoid arthritis extended to 4 years Rheumatology 2003; 42(3):422–426) | |||

| (Hewlett S; Kirwan J; Pollock J; Mitchell K; Hehir M; Blair PS; Memel D; Perry MG. Patient initiated outpatient follow up in rheumatoid arthritis: six year randomised controlled trial British Medical Journal 2005; 7484:171–175) | |||

| 58 | 1 | Vocational assessment | Gilworth G; Haigh R; Tennant A; Chamberlain MA; Harvey AR. Do rheumatologists recognize their patients’ work-related problems? Rheumatology 2001; 40(11):1206–1210 |

| 59 | 1 | Consultations éducatives (C.E.) | Dikaios M; Nguyen MF. Educative consultations on rheumatoid diseases at Cochin hospital: Application to rheumatoid arthritis. Rhumatologie 1995; 47(8):300–301 |

| 60 | 2 | Prise en charge pluridisciplinaire de la polyarthrite rhumatoide (multidisciplianary network); Un réseau pluridisciplinaire de prise en charge de la polyarthrite rhumatoide (reseau OPALE PR) | Fauquert P; Grardel B; Hardouin P; Meys E; Sutter B. Setting a multidisciplinary network for management of rheumatoid arthritis (OPALE PR Network). Rhumatologie 1995; 47(8):309–313 |

| 61 | 1 | Prise en charge globale pluridisciplinaire | Sany J. Multidisciplinary management for rheumatoid arthritis at Montpellier. Rhumatologie 1998; 50(7):208 |

| 62 | 2 | Prise en charge multidisciplinaire; Prise en charge globale | Le L; Vittecoq O; Bichon-Tauvel I; Dupray O. Multidisciplinary management for rheumatoid arthritis in Haute-Normandie. Rhumatologie 1998; 50(7):211–214 |

| 63 | 1 | Structure de traitement pluridisciplinaire de la polyarthrite rhumatoide | Beauvais C; Prier A; Berenbaum F; Molcard S; Le GL; Karneff A; Dumontier C; Sautet A; Pierre MM; Kaplan G. Multidisciplinary treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in St-Antoine Hospital. Rhumatologie 1998; 50(7):215–219 |

| 64 | 2 | Inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation program; outpatient rehabilitation | Nordstrom DC; Konttinen YT; Solovieva S; Friman C; Santavirta S. In- and out-patient rehabilitation in rheumatoid arthritis. A controlled, open, longitudinal, cost-effectiveness study. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology 1996; 25(4):200–206 |

| 65 | 1 | Multidisciplinary structured day care program | Jacobsson LTH; Frithiof M; Olofsson Y; Runesson I; Strombeck B; Wikstrom I. Evaluation of a structured multidisciplinary day care program in rheumatoid arthritis Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology 1998; 27(2):117–124 |

| 66 | 1 | La prise en charge pluridisciplinaire | Mazaud E; Poinsignon F; Prier A. [Rheumatoid arthritis. Interdisciplinary care]. Soins; La Revue de Reference Infirmiere 1996; (607):24–28 |

| 67 | 1 | Rheumatology clinic in the primary care setting | Kerr LD. The impact of rheumatology in the primary care setting: one rheumatologist’s odyssey. Southern Medical Journal 1995; 88(3):268–270 |

| 68 | 2 | Comprehensive outpatient care; traditional rheumatological (outpatient) care | Raspe HH; Deck R; Mattussek S. The outcome of traditional or comprehensive outpatient care for rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Results of an open, non-randomized, 2-year prospective study. Zeitschrift fur Rheumatologie 1992; 51(Suppl 1):61–66 |

References

- 1.Pincus T, O’Dell J. Combination therapy with multiple disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis: a preventive strategy. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:768. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-10-199911160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wollheim FA. Approaches to rheumatoid arthritis in 2000. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001;13:193–201. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200105000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fries JF. Current treatment paradigms in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2000;39(Suppl 1):30–35. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.rheumatology.a031492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis Guidelines Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002 update. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:328–346. doi: 10.1002/art.10148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emery P, Breedveld FC, Dougados M, Kalden JR, Schiff MH, Smolen JS. Early referral recommendation for newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis: evidence based development of a clinical guide. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:290–297. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.4.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, Anuntiyo J, Finney C, Curtis JR, Paulus HE, Mudano A, Pisu M, Elkins-Melton M, Outman R, Allison JJ, Almazor MS, Bridges SL, Jr, Chatham WW, Hochberg M, MacLean C, Mikuls T, Moreland LW, O’Dell J, Turkiewicz AM, Furst DE, American College of Rheumatology American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:762–784. doi: 10.1002/art.23721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li LC, Badley EM, MacKay C, Mosher D, Jamal S, Jones A, Bombardier C. An evidence-informed, integrated framework for rheumatoid arthritis care. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1171–1183. doi: 10.1002/art.23931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vliet Vlieland TPM, Zwinderman AH, Vandenbroucke JP, Breedveld FC, Hazes JMW. A randomized clinical trial of in-patient multidisciplinary treatment versus routine out-patient care in active rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:475–482. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.5.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill J. Patient satisfaction in a nurse-led rheumatology clinic. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:347–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campos AA, Graveline C, Ferguson JM, Lundon K, Schneider R, Laxer RM. The physical therapy practitioner: an expanded role for physical therapy in pediatric rheumatology. Physiother Can. 2001;53:282–287. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis P, Howard R, Brockway P. An evaluation of telehealth in the provision of rheumatologic consults to a remote area. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1910–1913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis P, Howard R, Brockway P. Telehealth consultations in rheumatology: cost-effectiveness and user satisfaction. J Telemed Telecare. 2001;7(Suppl 1):10–11. doi: 10.1258/1357633011936859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leggett P, Graham L, Steele K, Gilliland A, Stevenson M, O’Reilly D, Wootton R, Taggart A. Telerheumatology—diagnostic accuracy and acceptability to patient, specialist, and general practitioner. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:746–748. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pal B, Laing H, Estrach C. A cyberclinic in rheumatology. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1999;33:161–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pal B. Telemedicine. Pilot study of telephone follow up in rheumatology has just been completed. Br Med J. 1997;314:520–521. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, Pitkin R, Rennie D, Schulz KF, Simel D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276:637–639. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.8.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P, CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards of Reporting of Trials) Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:295–309. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li LC, Bombardier C. Setting priorities in arthritis care: Care III Conference. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1891–1894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hochberg MC, Chang RW, Dwosh IL, Lindsey S, Pincus T, Wolfe F. The American College of Rheumatology 1991 revised criteria for the classification of global functional status in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;353:498–502. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinbrocker O, Traeger CH, Batterman RC. Therapeutic criteria in rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA. 1949;140:659–662. doi: 10.1001/jama.1949.02900430001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anonymous (2005) Guideline Development Methods: Information for National Collaborating Centres and Guideline Developers. National Institute for Clinical Excellence, London. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx o=201982. Accessed April 30, 2005

- 22.Oandasan I, Baker GR, Barker C, Bosco D, D’Amour L, Jones S, Kimpton L, Lemieux-Charles L, Nasmith L, San Martin R, Tepper J, Way D. Teamwork in healthcare: promoting effective teamwork in healthcare in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacKay C, Devitt R, Soever L, Badley E (2005) An exploration of comprehensive interdisciplinary models for arthritis. Arthritis Community Research & Evaluation Unit (ACREU), Toronto Available at http://www.acreu.ca/pdf/pub5/05-03.pdf

- 24.Puolakka K, Kautiainen H, Mottonen T, Hannonen P, Pohjolainen T, Korpela M, Vuori K, Ilva K, Yli-Kerttula U, Jarvinen P, Leirisalo-Repo M. Cost of Finnish statutory inpatient rehabilitation and its impact on functional and work capacity of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: experience from the FIN-RACo trial. Scand J Rheumatol. 2007;36:270–277. doi: 10.1080/03009740701286847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Critchley S, Ball E. Evaluation of the primary/secondary care interface in relation to a primary care rheumatology service. Qual Prim Care. 2007;15:33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arvidsson SB, Petersson A, Nilsson I, Andersson B, Arvidsson BI, Petersson IF, Fridlund B, Petersson IF, Fridlund B. A nurse-led rheumatology clinic’s impact on empowering patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Nurs Health Sci. 2006;8:133–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2006.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nordmark B, Blomqvist P, Andersson B, Hagerstrom M, Nordh-Grate K, Ronnqvist R, Svensson H, Klareskog L. A two-year follow-up of work capacity in early rheumatoid arthritis: a study of multidisciplinary team care with emphasis on vocational support. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006;35:7–14. doi: 10.1080/03009740510026580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pace AV, Dowson CM, Dawes PT. Self-referral of symptoms (SOS) follow-up system of appointments for patients with uncertain diagnoses in rheumatology out-patients. Rheumatology. 2006;45:201–203. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz S, PJJr V, Moskowitz RW, Thompson HM, Svec KH. Comprehensive outpatient care in rheumatoid arthritis. A controlled study. JAMA. 1968;206:1249–1254. doi: 10.1001/jama.206.6.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vliet Vlieland TP, Hazes JM. Efficacy of multidisciplinary team care programs in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1997;27:110–122. doi: 10.1016/S0049-0172(97)80011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yelin EH. What’s inside the team care box? Is it the parts, the connections, the attention or the gestalt? J Rheumatol. 1991;18:1647–1648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anonymous (2006) Arthritis isn’t a big deal…until you get it. Report from the Summit on Standards for Arthritis Prevention and Care, November 1–2, 2005, Alliance for the Canadian Arthritis Program, Ottawa. Available at http://www.arthritisalliance.ca/docs/SAPC%20Full%20Report%2020060331%20en.pdf

- 33.Moher D, Dulberg CS, Wells GA. Statistical power, sample size, and their reporting in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1996;272:122–124. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, CONSORT The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2001;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boutron I, Moher D, Tugwell P, Giraudeauf B, Poiraudeaug S, Nizardh R, Ravaud P. A checklist to evaluate a report of a nonpharmacological trial (CLEAR NPT) was developed using consensus. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:1233–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moher D, Jones A, Lepage L, CONSORT Group (Consolitdated Standards for Reporting of Trials) Use of the CONSORT statement and quality of reports of randomized trials: a comparative before-and-after evaluation. JAMA. 2001;285:1992–1995. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mills EJ, Wu P, Gagnier J, Devereaux PJ. The quality of randomized trial reporting in leading medical journals since the revised CONSORT statement. Contemp Clin Trials. 2005;26:480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Egger M, Juni P, Bartlett C, CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards of Reporting of Trials) Value of flow diagrams in reports of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1996–1999. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.European Commission . Evaluating EU expenditure programmes. A guide. Ex post intermediate evaluation. 1. Luxenburg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bowen J, Ford RC. Managing service organizations: does having a “thing” make a difference. J Manage. 2002;28:447–469. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glasziou P, Meats E, Heneghan C, Shepperd S. What is missing from descriptions of treatment in trials and reviews. Br Med J. 2008;336:1472–1474. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39590.732037.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]