Abstract

Nursing is a hazardous occupation in the United States, but little is known about workplace health and safety issues facing the nursing work force in the Philippines. In this article, work-related problems among a sample of nurses in the Philippines are described. Cross-sectional data were collected through a self-administered survey during the Philippine Nurses Association 2007 convention. Measures included four categories: work-related demographics, occupational injury/illness, reporting behavior, and safety concerns. Approximately 40% of nurses had experienced at least one injury or illness in the past year, and 80% had experienced back pain. Most who had an injury did not report it. The top ranking concerns were stress and overwork. Filipino nurses encounter considerable health and safety concerns that are similar to those encountered by nurses in other countries. Future research should examine the work organization factors that contribute to these concerns and strengthen policies to promote health and safety.

Occupational injuries and illnesses among nurses are well documented in Western, developed countries. The key safety issues impacting this work force include needlestick injuries, workplace violence, and musculoskeletal injuries related to patient handling (Aiken, Sloane, & Klocinski, 1997; Catlette, 2005; de Castro, Hagan, & Nelson, 2006; Henderson, 2003; Jagger & Bentley, 1997; Nelson, Gross, & Lloyd, 1997; Nelson, Lloyd, Menzel, & Gross, 2003; Neuberger, Harris, Kundin, Bischone, & Chin, 1984; Porta, Handelman, & McGovern, 1999; Williams, 1996). More recently, concerns about workload, work hours, job stress, and fatigue have emerged (McNeely, 2005; Scott, Hwang, & Rogers, 2006; Trinkoff, Le, Geiger-Brown, & Lipscomb, 2007; Trinkoff, Le, Geiger-Brown, Lipscomb, & Lang, 2006; Trinkoff, Storr, & Lipscomb, 2001; Yip, 2001). These health issues are important not only for nurses themselves, but also because they may contribute to work force shortages by prompting nurses to leave the profession (Stone, Clarke, Cimiotti, & Correa-de-Araujo, 2004). Most studies examining occupational health and safety among nurses, however, have been conducted in North America and Europe.

An important national assessment of occupational health and safety issues comes from the 2001 American Nurses Association (ANA) Online Health and Safety Survey of nurses across the United States (Houle, 2001). About 4,800 respondents completed this survey, which encompassed topics such as (1) experience of a work-related injury or illness; (2) injury reporting behavior; (3) awareness and concerns about workplace hazards; and (4) availability of safety equipment and devices.

Notably, 41% of the ANA survey respondents had experienced a work-related injury in the past year, and 48% had experienced an illness that was caused or made worse by working as a nurse. About 44% felt only some-

Applying Research to Practice.

The significant number of nurses in the Philippines not reporting injuries and illnesses suggests the need for active surveillance tailored to this work force. Surveillance systems that capture health care-specific exposures among nurses are needed. Also, a national surveillance system that includes mechanisms for both employers and workers to report injuries and illnesses should be considered. Occupational health nurses in the Philippines should ensure that nurses understand the relationship between injury and illness and workplace factors by implementing educational and training strategies focusing on workplace health and safety. Given the hazards, concerns, and working conditions that nurses in the Philippines report, advocacy is needed at the national and organizational levels for the enforcement of occupational health and safety policies. Additionally, occupational health nurses can identify priority areas for research and can partner with researchers to investigate these issues more thoroughly.

what safe or not safe at all in their work environments, and 38% reported being inadequately informed by employers about workplace hazards. When asked to rank their top concerns, ANA respondents reported (1) acute and chronic effects of stress and being overworked; (2) a disabling back injury; and (3) being infected with a bloodborne pathogen from a needlestick. These injuries and illnesses appeared to be consequential not only for the nurse, but also for the workplace. About 23% reported missing 2 or more days in the past year due to a work-related injury or illness, and 76% reported that unsafe working conditions interfered with the delivery of quality nursing care (Houle, 2001).

Nurses in developed countries such as the United States may have safer working conditions than nurses in developing countries. This advantage may result from greater economic resources and regulatory oversight that support quality occupational health and safety protections. For example, in 1991, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) promulgated the Bloodborne Pathogen Standard to protect all workers at risk for exposure to bloodborne pathogens through sharps injuries or contact with skin or mucous membranes (OSHA, 1991). In contrast, the Philippines has no equivalent policy, even though the nursing profession is regulated by the Department of Labor and Employment and the Department of Health.

Although research into the occupational health and safety issues among nursing work forces outside Western, developed countries has been limited, these studies have been gaining increasing attention. For example, a number of studies have been published in recent years examining occupational exposures in health care settings throughout Africa, the Middle East, and Asia (Ansa, Udoma, Umoh, & Anah, 2002; Arafa, Nazel, Ibrahim, & Attia, 2003; Celik, Celik, Agirbas, & Ugurluoglu, 2007; Hiransuthikul, Tanthitippong, & Jiamjarasrangsi, 2006; Ilhan, Durukan, Aras, Turkcuoglu, & Aygun, 2006; Nsubuga & Jaakkola, 2005). Both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Council of Nurses (ICN) have expressed the need to better protect international health care work forces (“ICN, WHO lead effort to reduce needlesticks,” 2004; Wilburn & Eijkemans, 2004). The paucity of occupational health and safety research about nurses around the world, however, is a barrier to improving nurses’ workplace conditions.

No previous effort has been made to assess the occupational health and safety of this specific group. The current study was designed to gain preliminary insights into some of the occupational health and safety problems faced by nurses in the Philippines.

METHODS

Data Collection

This study was developed through a partnership between researchers at the University of Washington and the University of California, Los Angeles, with the Philippine Nurses Association (PNA) and the Occupational Health Nurses Association of the Philippines, Inc. (OHNAP). Data were collected from a survey of nurses attending the PNA annual national convention in October 2007. The convention attendees represented a wide spectrum of nursing roles (e.g., clinical care, administration, and education). Surveys, adapted from the 2001 ANA survey (Houle, 2001), were offered to the first 1,000 attendees registered at the convention. A total of 690 completed surveys were returned (response rate = 69%). Those who provided data were from all 13 regions of the Philippines, with 17% from the metropolitan Manila area and 21% from Agusan, where the convention was held (Table 1). Surveys were self-administered and anonymous and followed guidelines for human subjects protection specified by the University of Washington. Nurses completed all surveys in English, as English is widely used in the Philippines for business and education. The analyses excluded 21 respondents not currently working as registered nurses and another 14 who did not identify themselves as registered nurses, leaving a sample of 655 respondents.

Table 1. Work-Related Demographics (N = 655).

| % | |

|---|---|

| Type of work setting | |

| Education | 34.5 |

| Acute care hospital | 22.3 |

| Physician’s office, public health clinic, or freestanding ambulatory care center |

9.0 |

| Long-term care facility | 9.0 |

| Other | 5.8 |

| Company, corporation, or work site | 4.0 |

| Psychiatric facility | 0.3 |

| Correctional facility | 0.6 |

| Currently work as a bedside nurse | |

| Yes | 27.6 |

| No | 56.2 |

| Currently work in a management or supervi- sory position | |

| Yes | 68.4 |

| No | 20.2 |

| Time spent in direct patient care activities | |

| None | 11.2 |

| < 25% | 17.1 |

| 25% to 49% | 23.7 |

| 50% to 74% | 28.2 |

| ≥ 75% | 15.4 |

| Schedule usually worked in main nursing job | |

| Regular daytime | 61.8 |

| Regular night shift | 0.6 |

| Regular evening shift | 0.8 |

| Irregular schedule arranged by employer | 8.2 |

| Irregular schedule arranged by employee |

3.2 |

| Two-shift rotation (days/nights) | 4.9 |

| Three-shift rotation (days/evening/nights) | 1.4 |

| Other | 5.8 |

| Usual length of shift in main nursing job (hr) | |

| < 8 | 1.8 |

| 8 | 72.4 |

| 10 | 9.6 |

| 12 | 7.5 |

| > 12 | 4.3 |

| Times per month worked mandatory or un- planned overtime in main nursing job | |

| Never | 16.2 |

| 1 to 2 | 34.2 |

| 3 to 4 | 22.4 |

| 5 to 6 | 7.2 |

| 7 to 8 | 3.4 |

| > 8 | 10.2 |

| Average hours of overtime (combined) worked per month | |

| No overtime | 20.9 |

| 1 to 16 | 38.5 |

| 17 to 24 | 11.8 |

| 25 to 39 | 7.5 |

| 40 to 56 | 5.8 |

| 57 to 80 | 4.1 |

| > 80 | 4.0 |

| Have other job(s) for pay in addition to main nursing job | |

| Yes | 30.2 |

| No | 67.0 |

| Average hours worked per week in all jobs combined | |

| ≤ 20 | 4.1 |

| 21 to 40 | 30.1 |

| 41 to 60 | 53.9 |

| 61 to 80 | 6.9 |

| ≥ 81 | 2.4 |

| Philippine Nurses Association region | |

| National capital region (metropolitan Manila) |

17.4 |

| I: Ilocos region | 6.4 |

| II: Cagayan region | 4.7 |

| III: Bataan region | 2.7 |

| IV: Aurora region | 2.9 |

| V: Albay region | 3.4 |

| VI: Aklan region | 8.9 |

| VII: Bohol region | 3.5 |

| VIII: Leyte region | 2.7 |

| IX: Basilan region | 2.1 |

| X: Agusan region | 20.9 |

| XI: Davao region | 10.1 |

| XII: Cotabato region | 13.0 |

Note. For each category, “missing” constitutes remainder of percentage to total 100%.

Measures

Work-related demographics were measured using questions about type of work setting (e.g., acute care hospital or educational setting); currently working as a bedside nurse (yes/no); currently working in a management or supervisory position (yes/no); percent time spent in direct patient care activities (none, < 25%, 25% to 49%, 50% to 74%, or ≥ 75%); usual shift schedule (e.g., regular daytime or regular evening) and usual shift length (e.g., 8 or 12 hours); times per month working overtime (mandatory and unplanned); average hours of overtime worked per month; working in another job in addition to main nursing job (yes/no); and average number of hours worked per week in all jobs combined.

Occupational injuries and illnesses were assessed by asking respondents about the number of times they were injured on-the-job in the past year (0, 1 to 2, 3 to 4, or 5 or more); whether an illness was caused or made worse by working as a nurse (yes/no); whether they had missed more than 2 days of work in the past year due to a work-related injury or illness (yes/no); whether they had experienced back pain (yes/no); and if they had continued working despite experiencing back pain (often, sometimes, or never).

Reporting behavior was examined using two items. First, participants were asked how many occupational injuries they had reported to their employer (0, 1 to 2, 3 to 4, or 5 or more). If none of the injuries were reported, participants identified reasons why they did not report.

Safety concerns were explored in three dimensions: (1) perceived safety environment; (2) workplace hazards; and (3) top health and safety concerns. For perceived safety environment, the following were explored: do you feel safe from work-related injury or illness in the place where you work as a nurse (“not safe at all” to “very safe”); how good is your employer at keeping you informed about dangerous or unhealthy conditions you might be exposed to at work (“does not inform me at all” to “very good”); do unsafe working conditions interfere with the ability to deliver safe, quality care (“not at all” to “great extent”); and do health and safety concerns influence decisions about the kind of nursing work you do and continued practice in nursing (“not at all” to “great extent”). For workplace hazards, respondents answered yes or no to whether safer needle devices, patient lifting and transfer devices, and powdered latex gloves are available. They were also asked if they had been physically assaulted in the past year, and whether they had been threatened or had experienced verbal abuse in the past year. (The perpetrator of the violence was not solicited.) Additionally, respondents were asked to identify their top three health and safety concerns from a list of nine issues also used in the ANA survey (e.g., needlestick injuries or on-the-job assault).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated using the STATA 10.0 statistical package. Percentages were generated for each of the measures listed above to facilitate direct comparison with the reported data from the 2001 ANA survey (Houle, 2001).

RESULTS

Table 1 provides work-related demographics of the sample. Most respondents worked in education (35%) or acute care hospitals (22%). Slightly more than half (56%) were not currently working at the bedside. Sixty-eight percent worked in a managerial or supervisory position. However, about 44% did spend at least half of their work time in direct patient care activities. The majority had day shift schedules (62%) and worked 8-hour shifts (72%). Just more than one third worked 1 to 2 episodes of mandatory or unplanned overtime monthly and reported 1 to 16 hours of overtime per month. Thirty percent had other jobs in addition to their main nursing job. More than half (54%) worked 41 to 60 hours per week.

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for occupational injury and illness. Thirty-two percent of the respondents reported being injured 1 to 2 times in the past year, with another 6% having been injured at least 3 times. Forty-one percent reported an illness they thought was caused or worsened by working as a nurse. About one third (31%) noted they missed more than 2 days of work during the past year because of a work-related injury or illness. More than three fourths (78%) experienced back pain, and more than half (53%) often continued working despite this pain.

Table 2. Occupational Injury and Illness (N = 655).

| % | |

|---|---|

| Times injured on-the-job in the past year | |

| 0 | 61.4 |

| 1 to 2 | 31.5 |

| 3 to 4 | 4.4 |

| 5+ | 1.4 |

| Illness caused or made worse by working as a nurse | |

| Yes | 41.2 |

| No | 57.7 |

| Missed more than 2 days of work in the past year due to work-related injury or illness | |

| Yes | 31.0 |

| No | 67.8 |

| Experience back pain | |

| Yes | 78.2 |

| No | 19.4 |

| Continue working despite experiencing back pain | |

| Often | 52.7 |

| Sometimes | 28.6 |

| Never | 11.0 |

Note. For each category, “missing” constitutes remainder of percentage to total 100%.

Table 3 provides the number of injuries reported to the employer compared to the number of times injured among those experiencing an injury within the past year. Most participants underreported their injuries. For example, of those who experienced 3 to 4 injuries during the past 12 months, only 17% reported all of the injuries. Nearly half (47%) reported none. Similar patterns were seen for those with 1 to 2 injuries or 5 or more injuries.

Table 3. Reporting Behavior.

|

Number of Injuries Reported |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of Times Injured in Past Year |

0 | 1 to 2 | 3 to 4 | ≥ 5 | Missing |

| 1 to 2 (n = 216) | 89 (41.2%) | 123 (56.9%) | - | - | 4 (1.9%) |

| 3 to 4 (n = 30) | 14 (46.7%) | 11 (36.7%) | 5 (16.7%) | - | 0 |

| ≥ 5 (n = 9) | 4 (44.4%) | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 |

| Total | 107 | 137 | 6 | 1 | 4 |

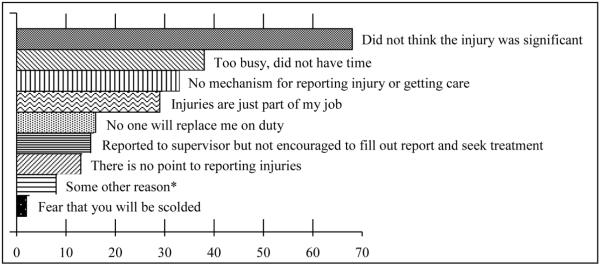

The Figure displays the reasons injuries were not reported for those who experienced at least one injury in the past year. The top three reasons were as follows: (1) “did not think the injury was significant”; (2) “too busy, did not have time”; and (3) “injuries are just part of my job.” Ranking eighth was “some other reason,” which included the following statements: “Health of personnel is not a priority of the institution/management/supervisor”; “It was my fault because I was not very careful at the time of the incident”; “I thought I could manage the injury and monitored it myself”; and “I somehow think it will count against me for being not very careful.”

Figure.

Reasons injuries were not reported among those who were injured at least once in the past year. Respondents were instructed to “check all that apply.” *Examples included the following: “Health of personnel is not a priority of the institution/management/supervisor”; “It was my fault because I was not very careful at the time of the incident”; “I thought I could manage the injury and monitored it myself”; and “I somehow think it will count against me for being not very careful.”

Table 4 provides information about nurses’ safety concerns. In terms of the perceived safety environment, 30% reported that they felt only “somewhat safe” or “not safe at all” from work-related injury or illness where they work as a nurse. Also, 32% reported that little or no information about dangerous or unhealthy conditions and exposures is provided by employers. About one third (33%) expressed that unsafe working conditions interfere with their ability to deliver safe, quality care to a moderate or great extent. Also, nearly 61% reported that health and safety concerns influenced their decisions about the kind of nursing work they did and continued practice in nursing to a moderate or great extent.

Table 4. Safety Concerns (N = 655).

| % | |

|---|---|

| Perceived safety environment | |

| Do you feel safe from work-related injury or illness in the place where you work as a nurse? | |

| Not safe at all | 9.2 |

| Somewhat safe | 21.2 |

| Moderately safe | 51.8 |

| Very safe | 16.3 |

| How good is your employer at keeping you informed about dangerous or unhealthy con- ditions you might be exposed to at work? | |

| Does not inform me at all | 10.7 |

| Poor; little information provided | 20.9 |

| Good; has informed me about hazards I did not know about |

35.0 |

| Very good; alerts me of all possible hazards | 26.4 |

| Do unsafe working conditions interfere with the ability to deliver safe, quality care? | |

| Not at all | 11.5 |

| Limited extent | 40.3 |

| Moderate extent | 28.2 |

| Great extent | 15.0 |

| Do health and safety concerns influence decisions about the kind of nursing work you do and continued practice in nursing? | |

| Not at all | 7.2 |

| Limited extent | 26.0 |

| Moderate extent | 33.3 |

| Great extent | 27.6 |

| Workplace hazards | |

| Safer needle devices provided | |

| Yes | 75.1 |

| No | 19.4 |

| Patient lifting and transfer devices available | |

| Yes | 41.5 |

| No | 51.2 |

| Powdered latex gloves used | |

| Yes | 80.0 |

| No | 14.5 |

| Physically assaulted in past year | |

| Yes | 7.0 |

| No | 90.2 |

| Threatened or experienced verbal abuse in past year | |

| Yes | 33.1 |

| No | 64.1 |

Note. For each category, “missing” constitutes remainder of percentage to total 100%. Ranking of top health and safety concerns: 1. acute and chronic effects of stress and overwork; 2. infection with respirable infectious disease; 3. needlestick; 4. disabling back injury; 5. toxic effects of exposure to chemicals, including reproductive effects; 6. on-the-job assault; 7. exposure to hazardous drugs (e.g., chemotherapy); 8. latex allergy; 9. exposure to smoke from electrocautery devices; and 10. other.

Most reported that some safety devices were available in their workplace, but the availability was by no means universal. The majority of nurses reported the presence of safer needle devices (75%). Fewer than half, however, reported patient lifting devices were provided (41%). Eighty percent reported that powdered latex gloves are available in their workplaces. Further, about 1 in 14 nurses (7%) reported being physically assaulted at work, while one third (33%) were threatened or verbally abused within the past year.

The respondents were asked to choose three safety and health concerns from a list provided based on ANA results. The three most frequently chosen concerns were, in order: (1) acute and chronic effects of stress and overwork; (2) infection with respirable infectious disease; and (3) needlestick injury. Some also listed other concerns, such as continuous standing, exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, unfair management, noise, lack of system managing bloody waste, exposure to ultraviolet rays used for environmental disinfection, and travel-related injuries.

DISCUSSION

This assessment of occupational health and safety among nurses who attended the PNA 2007 convention provides preliminary insight into the health and safety hazards that they encounter in the Philippine health care system.

Occupational Injury and Illness

A considerable portion of the respondents reported they had experienced work-related health problems during the past 12 months. Roughly one third mentioned a work-related injury. Moreover, about one third stated that they missed 2 or more days of work as a result of these injuries and illnesses. These proportions were similar to those reported by American nurses participating in the ANA survey (Houle, 2001). For example, 37% of this sample and 40% of the ANA survey respondents indicated a past-year work injury. These proportions should be interpreted with some caution because in both this sample and the ANA sample, about 30% had a second job, and it is possible that some of these injuries occurred when working that second job. However, these proportions are more than threefold higher than what was reported for a national sample of the U.S. general working population (11%; Waters, Dick, Davis-Barkley, & Krieg, 2007). The analyses suggest that future investigation is warranted and should provide comprehensive information on the type of injury, the severity, and the potential causes.

Nearly one third of Filipino nurses reported missing 2 or more days of work due to injury or illness. These findings are not atypical. For example, roughly one fourth of U.S. nurses also reported missing 2 or more days for work-related injury or illness (Houle, 2001). Potential reasons for these findings include underutilization of workers’ compensation, concerns of reprisals or loss of income for taking time off, reporting biases, and inadequate treatment for injured or sick nurses. Although the hypotheses could not be evaluated, future research should investigate them further.

This study found that more than three fourths (78%) of the respondents experienced back pain. The estimated prevalence of back pain for U.S. nurses ranges from 20% to 52% (Harber et al., 1985; Nelson, 2003; Owen, 1989). The causes of this pain are unclear. It is likely that some of this pain results from nursing work and some of it arises from other causes, such as a preexisting injury or work at a secondary job. Regardless of the cause, however, 81% of the respondents experiencing back pain said they continued to work despite the back pain. Because back pain is an important cause of disability, this acknowledgement of working after an injury suggests that ergonomic control measures (e.g., mechanical patient lifting equipment and training) may improve nurses’ well-being and, potentially, the quality of patient care.

Reporting Behavior

Although a large proportion of participants indicated a work-related injury, many did not report their injuries to their employers. Underreporting of work-related injuries and illnesses has also been noted as a significant problem among nurses in the United States (Brown et al., 2005; de Castro, 2003; Haiduven, Simpkins, Phillips, & Stevens, 1999; Siddharthan, Hodgson, Rosenberg, Haiduven, & Nelson, 2006; Tabak, Shiaabana, & Shasha, 2006). In part, low incident reporting in this sample was due to respondents feeling that the injury was not significant, but other key reasons were that nurses were too busy or felt that the injury was just “part of the job.” These reasons are concerning as they not only contribute to nurses working with injuries, but could also result in an artificially low injury rate. Efforts must be made to encourage nurses to report their injuries within their schedule to improve nurse outcomes and the accurate assessment of workplace health and safety.

Safety Concerns

About one third (30%) of Filipino nurses in this study reported that they felt either somewhat safe or not safe at all where they work as a nurse, compared to 44% of U.S. nurses (Houle, 2001). On the surface, this suggests that working conditions may be safer in the Philippines than in the United States. However, this difference may also reflect nurses’ lower expectations for safe working conditions. Currently, in the Philippines, nurses are not unionized and therefore do not have a formal mechanism to identify workplace hazards and advocate for improved working conditions. Characterizing Filipino nurses’ impressions and expectations of a safe work environment is another possible direction for research.

Two occupational hazards reported in this study are worth noting. First, a large majority (80%) of the respondents used powdered latex gloves. This raises concerns given the adverse effects of latex glove use (i.e., latex allergy and contact dermatitis). Because the prevalence of latex allergy and contact dermatitis has not been reported among nurses in the Philippines, it is recommended that an investigation into this potential problem be undertaken. Also, health care facilities should consider instituting a latex-free policy. Second, one third of the Filipino nurses in this study reported experiencing threats or verbal abuse. Even physical assault was reported by 7% of the respondents. Workplace violence is a serious problem among nurses (Henderson, 2003; Kingma, 2001). In the United States, patients and coworkers (including physicians and other nurses) are the major sources of workplace violence against nurses. Acts of violence may be motivated by a sense of entitlement among patients, physicians, and other nurses with more seniority. The researchers did not inquire about the source of workplace violence among the respondents, however. It is possible that violence against health care professionals is less a part of patient and coworker behavior in the Philippines, or that the perpetrator profile is different altogether (e.g., only physicians or patients’ family members). Given the number of respondents who reported experiencing threats or verbal abuse, this is certainly worthy of continued investigation.

To assess whether nurses in the Philippines and nurses in the United States are concerned about similar health and safety issues, the researchers asked respondents to rank order the concerns reported by the ANA survey respondents. In the current study, the highest ranked concern was the same as for the ANA survey (Houle, 2001): acute and chronic effects of stress and overwork. Previous research has noted that certain work organization factors contribute to stressful working conditions, which can ultimately lead to staff turnover or nurses leaving the profession entirely (Erenstein & McCaffrey, 2007; Escriba-Aguir, Martin-Baena, & Perez-Hoyos, 2006; Estryn-Behar et al., 2007; Hochwalder, 2007). However, as mentioned, most of these studies were conducted in Western countries. The researchers hypothesize that similar work organization factors have comparable effects among Filipino nurses; however, no study along these lines has been conducted to the authors’ knowledge. Given that the current survey was modeled after the ANA survey, some items that may have been particularly important in the Philippines were omitted (e.g., loss of electricity or “brain drain” to developed countries). It would be important for a future study to provide an open-ended structure to investigate these potential issues and to assess their relative rankings.

Limitations

Although these nurse participants come from all regions of the Philippines, this sample was derived from nurses who attended the PNA 2007 annual national convention. Therefore, nurses should be mindful that these findings cannot be generalized to the entire population of nurses in the Philippines. Additionally, survey items developed for American nurses were used. Although this technique provided the advantage of comparability, it is likely that some issues particularly relevant to Filipino nurses are not represented in this survey. As a corollary, several of the indicators used in this study are fairly crude and do not necessarily capture the complexity of working conditions encountered by nurses. For instance, 30% of the respondents had a second job and, accordingly, some of the findings presented here may reflect their experiences based on the second job and not their primary nursing job. Finally, about 30% of PNA attendees declined to complete the survey, which may introduce potential sampling biases. Future studies can employ qualitative methods to complement and extend the current investigation.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

This study suggests several ways to improve occupational health and safety among Filipino nurses. First, the underreporting of injuries and illnesses found in this study indicates that injury and illness surveillance specifically designed for the nursing work force in the Philippines could be useful in better identifying problems. The Philippine Bureau of Working Conditions collects the Work Accident Injury Report (WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, 2006). Because this system relies on employers to provide information, underreporting may be a problem. In addition to the incidence of workplace injury and illness, a surveillance system that captures health care-specific exposures such as hazardous drugs and bloodborne pathogens would inform intervention strategies for improving nurses’ health and well-being.

The underreporting of occupational injuries and illnesses found in this study also highlights an important role for occupational health nurses: to explore strategies to help nurses recognize the potential seriousness of work-related injuries and illnesses. For example, increased education and training that facilitates nurses’ understanding of the connection between workplace factors and their injuries and illnesses may be in order. This could occur at various levels, such as launching a national campaign organized by the PNA and OHNAP, holding frequent seminars for staff within organizations, and incorporating health and safety content within nursing school curricula.

Occupational health nurses must advocate for occupational health and safety policies. At the national level, these policies should include formalized regulations with enforcement mechanisms. This way, health care organizations will be responsible and accountable for maintaining a healthy and safe work environment for their nursing staffs. Policies that address the prevention of occupational injury and illness can also be adopted within the health care workplace. Occupational health nurses can be particularly effective at this level by directly monitoring workplace exposures and advocating to management for actions that protect workers.

Finally, future research is recommended with this worker population. Occupational health nurses in health care settings can play a vital role by partnering with researchers to explore the issues found with this assessment. Some potential priority areas include job stress, the impact of verbal abuse on nurse well-being, and factors that contribute to back pain. Occupational health nurses are in optimal positions to identify research needs and facilitate study participation among the nursing work force they serve.

CONCLUSION

Studies in the United States and other Western countries suggest that nurses face considerable occupational health and safety risks. Although preliminary, this survey suggests many commonalities in the types of issues reported by nurses attending the 2007 PNA annual national convention and nurses elsewhere. Many respondents reported helpful workplace policies and practices, such as the provision of patient lifting devices, but about one third of the sample reported poor or no employer information related to nursing occupational hazards. Future research should verify these findings and assess the potential interventions that may enhance nurses’ health and well-being and promote quality patient care.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

REFERENCES

- Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Klocinski JL. Hospital nurses’ occupational exposure to blood: Prospective, retrospective, and institutional reports. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(1):103–107. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansa VO, Udoma EJ, Umoh MS, Anah MU. Occupational risk of infection by human immunodeficiency and hepatitis B viruses among health workers in south-eastern Nigeria. East African Medical Journal. 2002;79(5):254–256. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v79i5.8863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arafa MA, Nazel MW, Ibrahim NK, Attia A. Predictors of psychological well-being of nurses in Alexandria, Egypt. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2003;9(5):313–320. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-172x.2003.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JG, Trinkoff A, Rempher K, McPhaul K, Brady B, Lipscomb J, et al. Nurses’ inclination to report work-related injuries: Organizational, work-group, and individual factors associated with reporting. AAOHN Journal. 2005;53(5):213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catlette M. A descriptive study of the perceptions of workplace violence and safety strategies of nurses working in level I trauma centers. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2005;31(6):519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celik SS, Celik Y, Agirbas I, Ugurluoglu O. Verbal and physical abuse against nurses in Turkey. International Nursing Review. 2007;54(4):359–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro AB. Barriers to reporting a workplace injury. American Journal of Nursing. 2003;103(8):112. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200308000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro AB, Hagan P, Nelson A. Prioritizing safe patient handling: The American Nurses Association’s Handle With Care Campaign. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2006;36(7–8):363–369. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200607000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erenstein CF, McCaffrey R. How healthcare work environments influence nurse retention. Holistic Nursing Practice. 2007;21(6):303–307. doi: 10.1097/01.HNP.0000298615.25222.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escriba-Aguir V, Martin-Baena D, Perez-Hoyos S. Psychosocial work environment and burnout among emergency medical and nursing staff. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2006;80(2):127–133. doi: 10.1007/s00420-006-0110-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estryn-Behar M, Van der Heijden BI, Oginska H, Camerino D, Le Nezet O, Conway PM, et al. The impact of social work environment, teamwork characteristics, burnout, and personal factors upon intent to leave among European nurses. Medical Care. 2007;45(10):939–950. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31806728d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiduven DJ, Simpkins SM, Phillips ES, Stevens DA. A survey of percutaneous/mucocutaneous injury reporting in a public teaching hospital. Journal of Hospital Infection. 1999;41(2):151–154. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(99)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harber P, Billet E, Gutowski M, SooHoo K, Lew M, Roman A. Occupational low-back pain in hospital nurses. Journal of Occupational Medicine. 1985;27(7):518–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson AD. Nurses and workplace violence: Nurses’ experiences of verbal and physical abuse at work. Nursing Leadership (Toronto, Ont.) 2003;16(4):82–98. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2003.16263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiransuthikul N, Tanthitippong A, Jiamjarasrangsi W. Occupational exposures among nurses and housekeeping personnel in King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 2006;89(Suppl 3):S140–S149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochwalder J. The psychosocial work environment and burn-out among Swedish registered and assistant nurses: The main, mediating, and moderating role of empowerment. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2007;9(3):205–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houle J. American Nurses Association Nursingworld.org health and safety survey. Cornerstone Communications Group; Warwick, RI: 2001. Nursingworld.org [Google Scholar]

- ICN WHO lead effort to reduce needlesticks. International Nursing Review. 2004;51(1):11–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilhan MN, Durukan E, Aras E, Turkcuoglu S, Aygun R. Long working hours increase the risk of sharp and needlestick injury in nurses: The need for new policy implication. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;56(5):563–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger J, Bentley MB, Collaborative EPINet Surveillance Group Injuries from vascular access devices: High risk and preventable. Journal of Intravenous Nursing. 1997;20(Suppl 6):S33–S39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingma M. Workplace violence in the health sector: A problem of epidemic proportion. International Nursing Review. 2001;48(3):129–130. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-7657.2001.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely E. The consequences of job stress for nurses’ health: Time for a check-up. Nursing Outlook. 2005;53(6):291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A. State of the science in patient care ergonomics: Lessons learned and gaps in knowledge; Paper presented at the Third Annual Safe Patient Handling and Movement Conference; Clearwater Beach, FL. 2003, March 5. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A, Gross C, Lloyd J. Preventing musculoskeletal injuries in nurses: Directions for future research. SCI Nursing. 1997;14(2):45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A, Lloyd JD, Menzel N, Gross C. Preventing nursing back injuries: Redesigning patient handling tasks. AAOHN Journal. 2003;51(3):126–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuberger JS, Harris JA, Kundin WD, Bischone A, Chin TD. Incidence of needlestick injuries in hospital personnel: Implications for prevention. American Journal of Infection Control. 1984;12(3):171–176. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(84)90094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nsubuga FM, Jaakkola MS. Needle stick injuries among nurses in sub-Saharan Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2005;10(8):773–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration . Bloodborne pathogens. 1991. 29 C.F.R. 1910.1030. [Google Scholar]

- Owen BD. The magnitude of low-back problems in nursing. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1989;11(2):234–242. doi: 10.1177/019394598901100208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta C, Handelman E, McGovern P. Needlestick injuries among health care workers: A literature review. AAOHN Journal. 1999;47(6):237–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LD, Hwang WT, Rogers AE. The impact of multiple care giving roles on fatigue, stress, and work performance among hospital staff nurses. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2006;36(2):86–95. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200602000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddharthan K, Hodgson M, Rosenberg D, Haiduven D, Nelson A. Under-reporting of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in the Veterans Administration. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance: Incorporating Leadership in Health Services. 2006;19(6–7):463–476. doi: 10.1108/09526860610686971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone PW, Clarke SP, Cimiotti J, Correa-de-Araujo R. Nurses’ working conditions: Implications for infectious disease. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10(11):1984–1989. doi: 10.3201/eid1011.040253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabak N, Shiaabana AM, Shasha S. The health beliefs of hospital staff and the reporting of needlestick injury. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2006;15(10):1228–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkoff AM, Le R, Geiger-Brown J, Lipscomb J. Work schedule, needle use, and needlestick injuries among registered nurses. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2007;28(2):156–164. doi: 10.1086/510785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkoff AM, Le R, Geiger-Brown J, Lipscomb J, Lang G. Longitudinal relationship of work hours, mandatory overtime, and on-call to musculoskeletal problems in nurses. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2006;49(11):964–971. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkoff AM, Storr CL, Lipscomb JA. Physically demanding work and inadequate sleep, pain medication use, and absenteeism in registered nurses. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2001;43(4):355–363. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200104000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters TR, Dick RB, Davis-Barkley J, Krieg EF. A cross-sectional study of risk factors for musculoskeletal symptoms in the workplace using data from the General Social Survey (GSS) Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2007;49(2):172–184. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3180322559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilburn SQ, Eijkemans G. Preventing needlestick injuries among healthcare workers: A WHO-ICN collaboration. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2004;10(4):451–456. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2004.10.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MF. Violence and sexual harassment: Impact on registered nurses in the workplace. AAOHN Journal. 1996;44(2):73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific Country report: Philippines. 2006 Retrieved October 20, 2009, from www.wpro.who.int/NR/rdonlyres/26CC7FD5-E412-4C99-BA13-C24883B501B7/0/PHLcountryprofile.pdf.

- Yip Y. A study of work stress, patient handling activities and the risk of low back pain among nurses in Hong Kong. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;36(6):794–804. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.02037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]