Abstract

The current study quantifies the contribution of each of the four unique inhibiting heterotropic interactions between the allosteric inhibitor, phospho(enol)pyruvate (PEP), and the substrate, fructose-6-phosphate (Fru-6-P), in phosphofructokinase from E. coli (EcPFK). The unique heterotropic interactions, previously labeled by the distances between ligand binding sites, were isolated independently by constructing hybrid tetramers. Of the four unique heterotropic PEP/Fru-6-P interactions, the 45Å interaction contributed 25%, the 30Å contributed 31% and the 23Å contributed 42% of the total PEP inhibition. The 33Å interaction actually causes a small activation of Fru-6-P binding by PEP and therefore contributed -8% of the total observed PEP inhibition. The pattern of relative contribution to PEP inhibition from each interaction in EcPFK does not follow the same pattern seen in MgADP activation of EcPFK. This observation supports the conclusion that although PEP and MgADP bind to the same site, they do not use the same communication pathways to influence the active site. The pattern of relative contribution describing PEP inhibition observed in this study also does not follow the pattern determined for PEP inhibition in phosphofructokinase from Bacillus stearothermophilus, suggesting that these two highly homologous isoforms are not inhibited in the same manner by PEP.

Phosphofructokinase (PFK)1 catalyzes the transfer of a phosphate group from MgATP to Fru-6-P with the production of MgADP and Fru-1,6-BP. The reaction catalyzed by PFK is the first committed step in glycolysis. Consequently, PFK is a major regulation point of this metabolic pathway, and accordingly PFK from E. coli (EcPFK) displays both allosteric activation by MgADP and allosteric inhibition by phospho(enol)pyruvate (PEP) (1). Since the allosteric effectors of EcPFK alter affinity for Fru-6-P without affecting the maximal activity, both MgADP and PEP are classified as K-type effectors (1).

EcPFK is a homotetramer (2, 3), with each subunit having a molecular weight of 34 kDa. The four subunits are assembled as a dimer of dimers resulting in two types of subunit interfaces. Four active sites are formed at one type of subunit interface while four allosteric sites are formed at the second interface. The allosteric inhibitor, PEP, and the allosteric activator, MgADP, compete for binding to the same allosteric binding site (2).

As a result of this configuration, there are 28 possible through-protein, ligand-ligand interactions between the binding of Fru-6-P at the four active sites and the binding of either PEP or MgADP at the four allosteric sites, and all of these interactions may contribute to the overall regulation of Fru-6-P binding to EcPFK. Of these interactions, 10 are potentially unique, non-symmetry- related interactions: 3 homotropic involving the binding of Fru-6-P, 3 homotropic involving the binding of either PEP or MgADP, and 4 are heterotropic interactions between the binding of Fru-6-P and the binding of the allosteric ligands. We have previously isolated and characterized each of the four unique activating heterotropic interactions between MgADP and Fru-6-P in EcPFK (4, 5) and the four unique inhibiting interactions between PEP and Fru-6-P in PFK from B. stearothermophilus (BsPFK) (6, 7). These interactions were isolated in 1:3 hybrid tetramers that each had only one native Fru-6-P binding site and one native allosteric site (designated 1|1)2.

When these results are compared, significant differences between the coupling patterns are evident. The 22Å interaction3 contributes most strongly to the PEP inhibition of BsPFK while the 32Å interaction contributes from 50–80% of that amount (in terms of free energy) depending on pH. This pattern is essentially reversed for the analogous 23Å and 33Å interactions involved in the MgADP activation of EcPFK. Perhaps most striking is the fact that the 30Å interaction does not contribute at all to the PEP inhibition of BsPFK at low pH, while the 30Å interaction contributes substantially at all pH values in the MgADP activation of EcPFK. The question remains whether these differences are due to the different allosteric effects being assessed in each case, or whether these differences are attributable to the different isoforms of the enzyme, or both. The goal of the current work was to characterize the four unique inhibitory heterotropic interactions between Fru-6-P and PEP isolated in 1:3 hybrid tetramers of EcPFK to directly address these possibilities.

Material and Methods

Materials

All chemical reagents were analytical grade, purchased from Fisher or Sigma. Mimetic Blue 1 agarose resin from Prometic Biosciences was used in protein purification. Creatine phosphate, the sodium salts of Fru-6-P, Fru-1,6-BP, ATP, and PEP were purchased from Sigma. Creatine kinase, aldolase, rabbit muscle triosephosphate isomerase and glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase were obtained from Boehringer Mannheim.

Protein Expression and Purification

All variants of EcPFK used in this study were constructed as previously described (4, 5). Wild type and mutant proteins were expressed in DF1020 cells (9, 10) as previously described (11). The methodology for hybrid formation and separation has previously been discussed (5). These methods include subunit exchange in the presence of KSCN and the addition of a surface charge modification (K2E/K3E) to mutated subunits to increase separation when eluting with a linear NaCl gradient from a Mono-Q 10/10 (Pharmacia) FPLC ionic exchange column. Subunit exchange of isolated 1:3 hybrids was prevented by adding Fru-6-P to the buffers used in hybrid separation and storage (4).

PFK Kinetic Assays

PFK activity measurements were carried out in 600 μl of an EPPS buffer containing 50 mM EPPS-KOH (pH 8.0 at 8.5°C), 10 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 0.2 mM NADH, 150 μg aldolase, 30 μg glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, 4 mM creatine phosphate, 24 μg creatine kinase and 3 mM ATP. Initial assays were with 3 μg triosephosphate isomerase per 600μl assay but were increased to 50 μg triosephosphate isomerase per 600μl assay at high PEP concentrations to overcome PEP inhibition of the triosephosphate isomerase activity. Fru-6-P and PEP concentrations were varied as indicated. Addition of EcPFK was used to initiate the enzymatic reaction, which was monitored at 340 nm over time. A unit (U) of activity is defined as the amount of enzyme required to produce 1 μmole of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate per minute.

Data Analysis

Data were fit to appropriate equations using the non-linear least squares fitting analysis of Kaleidagraph (Synergy) software. Tetramers with sufficient affinity for Fru-6-P to allow for extrapolation to Vmax were fit to the following form of the Hill equation (12):

| (1) |

where v = initial rate, ET = total enzyme active site concentration, kcat = turnover number, K0.5 = the concentration of Fru-6-P that yields a rate equal to one half the maximal specific activity, and nH = the Hill coefficient. For hybrids with a single native active site, the linear region (at low Fru-6-P concentration) of the Fru-6-P saturation curves were fit to:

| (2) |

A plot of 1/(kcat/Km) or K0.5 vs. PEP concentration allowed for a fit to (13):

| (3) |

where Kapp = K0.5 when data were fit to Equation 1, and Kapp = the reciprocal of kcat/Km when data were fit to Equation 2, as discussed in the text. when [PEP] = 0, = the dissociation constant for PEP when [Fru-6-P] = 0 and the co-substrate MgATP is saturating, and Qay/b = the coupling constant between PEP and Fru-6-P with MgATP saturating.

Qay/b is a measure of both the influence that PEP has on Fru-6-P binding and that Fru-6-P has on PEP binding in the saturating presence of MgATP. Qay/b is equal to the ratio of the dissociation constants for one ligand in the absence and saturating presence of the other, respectively (14) and can be related to free energy by (15):

| (4) |

where R = the Gas Constant, T = absolute temperature in Kelvin, and ΔGay/b is the coupling free energy beteen Fru-6-P and PEP when MgATP is saturating.

Qay/b, determined for 1|1 hybrids, were corrected for contributions from the mutated allosteric sites as described previously (4, 5) and summarized below. This correction was accomplished by measuring the apparent coupling obtained from respective 1|0 control hybrids (4, 5). In all cases the corrections were small or negligible. The corrected data were then fit to Equation 3.

Results

Mutations Used for Hybrid Formation

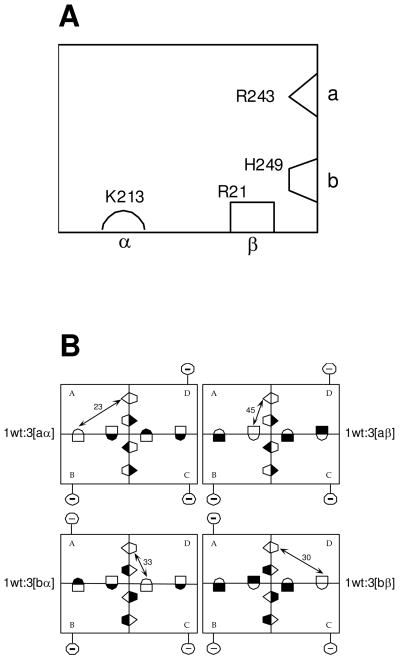

The purpose of this investigation was to quantify the four potentially unique heterotropic inhibitory interactions between PEP and Fru-6-P in the EcPFK tetramer. In a previous paper, we described the construction and isolation of 4 different 1:3 hybrid tetramers each of which consists of a different structural disposition between the 1 native active site and the 1 native allosteric site each contains (4). Consequently each of these hybrids isolates one of the 4 individual, potentially unique, site-site interactions that comprise the heterotropic allosteric communication network in EcPFK. The non-native sites in these 1:3 hybrids have been modified so they exhibit greatly diminished affinity for their respective ligands. Adding a surface charge mutation, K2E/K3E, to the modified subunits facilitates separation of various hybrid species by ion exchange chromatography. Despite the number of mutations required to construct these 4 hybrids, we have shown that together they account for all of the heterotropic allosteric activation by MgADP manifested in EcPFK (4). Schematic diagrams summarizing the hybrid construction are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of a single subunit of E. coli PFK. The two complementary halves of each active site are labeled ‘a’ and ‘b’ respectively, while the two complementary halves of each allosteric site are labeled ‘α’ and ‘β’ respectively. Residues are depicted in each half-site which, when modified to glutamate (or alanine in the case of R21), greatly diminish either Fru-6-P or PEP binding to the entire active site or allosteric site, respectively. (B) A schematic for the four hybrid tetramers that isolate each of the four unique heterotropic interactions contained in wild-type EcPFK. Allosteric sites are depicted as lying along the horizontal dimer-dimer interface, while the Fru-6-P portion of the active site lies along the vertical dimer-dimer interface. Each hybrid is obtained from the 1:3 combination of a wildtype parent and one of 4 modified parent proteins, the latter designated aα, aβ, bα, bβ respectively depending on the location of the mutations, as described in A, and denoted with a filled half-binding site symbol. Reference to X-ray structures allows the unambiguous determination of the relationship between the single unmodified substrate site and single unmodified allosteric site that remain in each 1:3 hybrid. Purification of 1:3 hybrids is facilitated by the changes introduced in 2 charged residues located on the surface of the modified parent proteins, depicted in the figure by the circled negative sign connected to each modified subunit. Details can be obtained from reference (4) from which these figures were taken.

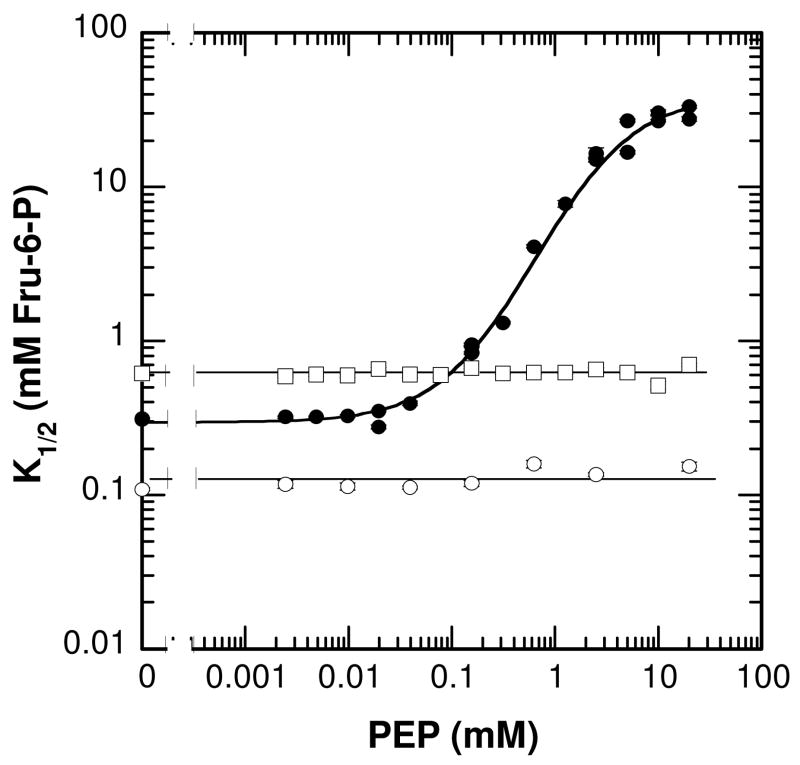

Since 1:3 hybrids were previously used to study MgADP activation (4,5), we wished to use the same hybrids to study PEP inhibition. It has previously been established that PEP binds competitively to the same allosteric site as MgADP (2). The mutations on either side of the interface within the Fru-6-P binding site, R243E and H249E respectively, have been shown to each diminish binding of Fru-6-P to the sites in which they were incorporated (4, 5). However, it is necessary to demonstrate that the modifications that eliminated MgADP binding at the allosteric site would have a similar effect on PEP binding to those same sites. The two mutations used to reduce MgADP affinity were R21A and K213E, which lie on opposite sides of the subunit interface the binding site straddles. These two mutations were analyzed with respect to their ability to decrease PEP affinity. Plotting K1/2 for Fru-6-P binding vs. PEP concentration over the accessible PEP concentration range shows no PEP inhibition of Fru-6-P affinity in either the R21A or K213E mutations (Figure 2). These results are also consistent with the role of R21 and K213 in PEP binding previously proposed by Lau and Fersht (16). Although the lack of allosteric affect does not distinguish between the absence of PEP binding and failure of the allosteric site to communicate with the Fru-6-P binding site, for our current purpose either property is sufficient. The K2E/K3E charge tags also do not have any affect on the coupling between Fru-6-P and PEP (data not shown). Therefore we used the previously designed 1:3 hybrid tetramers to individually isolate each of the four unique heterotropic interactions between Fru-6-P and PEP in EcPFK (4, 5).

Figure 2.

The apparent K 1/2 for Fru-6-P vs. PEP concentration for wild-type (λ), R21A (□), K213E (○). The curve through wild type data represents the best fit to Equation 3.

The hybrids are designed so that one can quantify the inhibition of Fru-6-P binding to a single unmodified active site that results from the binding of PEP to a single unmodified allosteric site. This is accomplished by creating weakened interactions between PEP and the other three allosteric sites via either the R21A or K213E modifications. However, since PEP inhibits by weakening the interaction of Fru-6-P with the active site, and linkage requires that Fru-6-P will also weaken the binding of PEP to the native allosteric site. Therefore we incorporated two experimental strategies to assure that the PEP effects we observe can be attributed exclusively to the interaction between the binding of Fru-6-P and PEP to their respective native binding sites on the 1|1 hybrids.

The first experimental precaution was to assess the effects of PEP on kcat/Km for Fru-6-P rather than Km. kcat/Km can be assessed at very low Fru-6-P concentrations (relative to Km) according to equation (2) thus removing the need to utilize the high Fru-6-P concentrations that would substantially weaken the affinity of PEP to the native allosteric site. The potential weakness of this approach is of course the ambiguity with which Km is inferred, since effects of PEP on kcat would also modify the value of kcat/Km. However, we have established previously (17) that PEP does not affect kcat in wild-type EcPFK, so we would not expect it to effect the kcat associated with the turnover of the single native active site functional at low concentrations of Fru-6-P in these hybrids.

To further ensure that any weak PEP interactions with the modified allosteric sites in the hybrid tetramers were not contributing to the observed inhibition, two 1|0 control hybrids, in which all the allosteric sites are modified, were also constructed as previously described (4, 5). The 1|021 control (a hybrid tetramer in which one subunit contains R21A in the allosteric site and three contain K2E/K3E/R21A/R243E) serves as a control for the 45Å and 30Å interactions. The 1|021 control has a coupling constant, Qay/b, equal to 0.93 ± 0.08 at 8.5°C indicating very little inhibition can be attributed to interactions as the weakened sites. Nonetheless, the inhibition measured for both the 45Å and 30Å isolated interactions were corrected to account for this small contribution from the modified allosteric sites by dividing the observed kcat/Km values obtained with the 1|1 hybrids that isolate the 45Å and 30Å interactions by the corresponding kcat/Km value obtained for the 1|021 control. The analogous 1|0213 control hybrid was made with one subunit containing a K213E modification (in the allosteric site) and three subunits contain K2E/K3E/K213E/H249E. Qay/b for this 1|0213 control is equal to 0.90 ± 0.7 at 8.5°C confirming that PEP barely inhibits when binding to allosteric sites modified with K213A. The inhibitory couplings measured for both the 33Å and 23Å interactions were similarly corrected for this small contribution as just described.

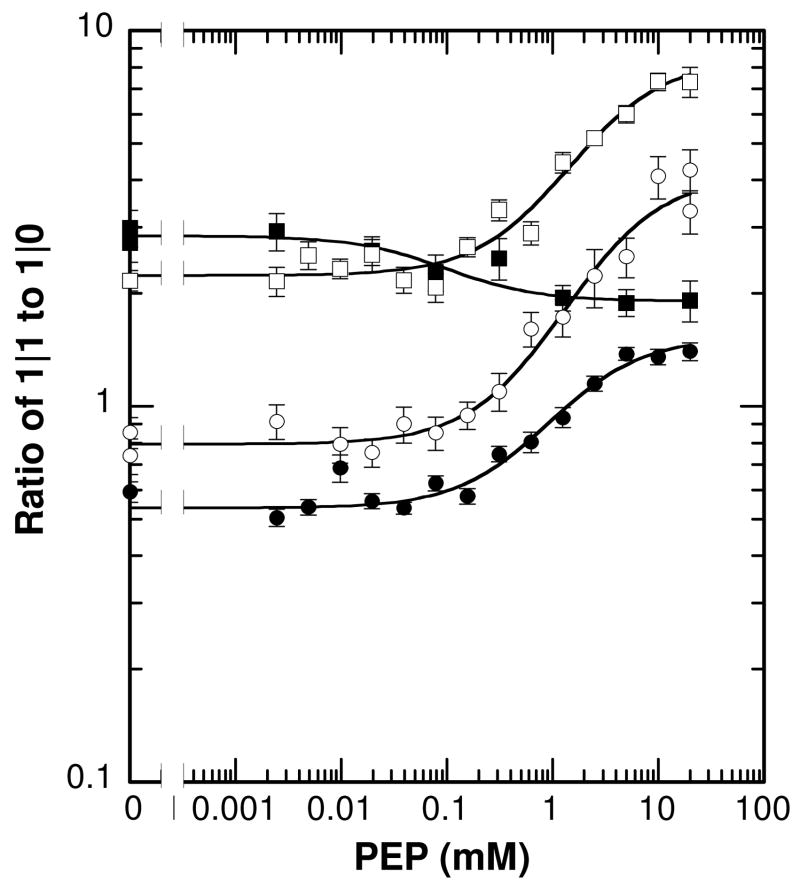

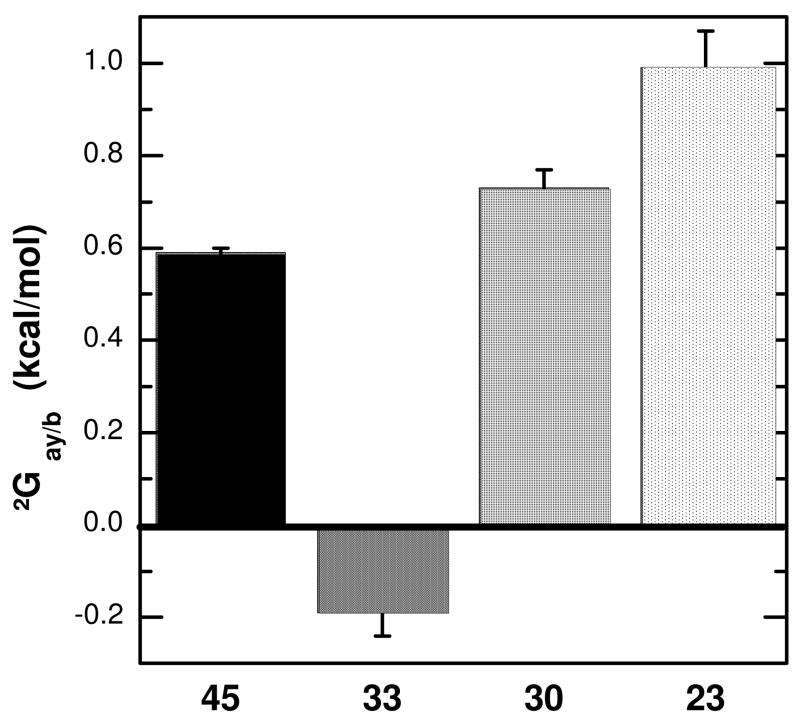

The corrected data for each of the four unique inhibitory heterotropic interactions collected at 8.5°C are presented in Figure 3, and the parameters from the corresponding fits to Equation 3 are listed in Table 1. The 45Å, 30Å, and 23Å interactions have coupling free energies (ΔGay/b) equal to +0.59 ± 0.02 kcal/mol, +0.73 ± 0.04 kcal/mol, and +0.99 ± 0.07 kcal/mol, respectively. Surprisingly, the coupling free energy for the 33Å interaction between PEP and Fru-6-P is slightly activating, with ΔGay/b equal to −0.19 ± 0.04 kcal/mol. These results are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Dependence of Km/kcat on PEP concentration for each of the individual heterotropic interactions: 45Å (λ), 33Å (■),30Å (□), and 23Å (○). Data are presented as the ratio of the data obtained with 1|1 constructs to the data obtained with the respective 1|0 control as described in the text. Error bars are present for all data points. Lines represent best fits to Equation 3 and the resulting parameters are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters from Linkage Analysis Obtained at 8.5°C for PEP Inhibition of EcPFK

| Interaction | Qay/b | ΔGay/b (kcal/mol) | % Contributiona |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1|4 Control | 0.0142±0.0005 | 2.38±0.03 | 100 |

| 45Å | 0.35±0.01 | 0.59±0.02 | 25±1 |

| 33Å | 1.4±0.1 | −0.19±0.04 | −8±2 |

| 30Å | 0.27±0.02 | 0.73±0.04 | 31±2 |

| 23Å | 0.17±0.02 | 0.99±0.07 | 42±3 |

| 45Å+33Å+30Å +23Å | -------- | 2.12±0.09 | 89±4 |

| 45Å+30Å+23Å | -------- | 2.31±0.08 | 97±4 |

%Contribution with respect to ΔGay/b @8.5°C determined for the 1|4 control.

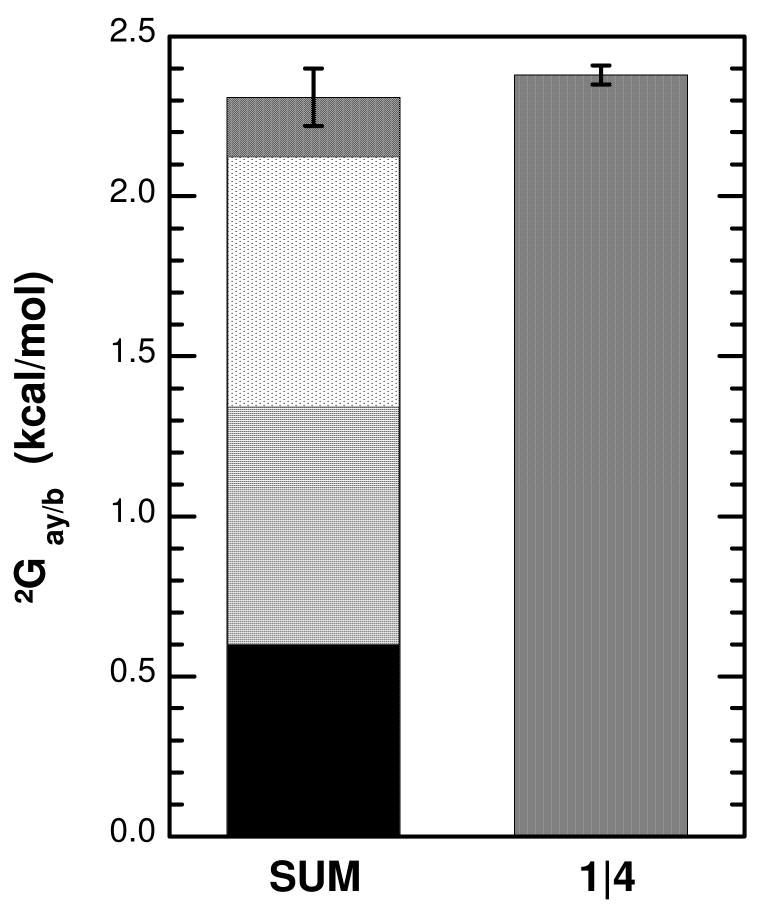

Figure 4.

The coupling free energies determined from the data shown in Figure 3 for each of the isolated inhibitory interactions.

Total Heterotropic Inhibition

Total heterotropic inhibition exhibited by a homodimer can be impacted by changes in the homotropic interactions involving either substrate or inhibitor resulting from saturation by the heterotropic ligand (18). One can anticipate similar behavior in a homotetramer. Since the 1|1 hybrids are incapable of exhibiting homotropic cooperativity, but the wild type tetramer is known to exhibit homotropic cooperativity in its interactions with Fru-6-P (1), an additional control hybrid was constructed in which 1 native active site interacts with all 4 allosteric sites simultaneously (1|4) to estimate the total heterotropic interactions that occur in the tetramer in the absence of homotropic effects. This assessment was made by estimating kcat/Km for Fru-6-P at low Fru-6-P concentrations to mimic the assessments made of the 1|1 hybrids. The Hill coefficient for PEP interaction to wild-type enzyme is equal to 1 at low Fru-6-P concentrations indicating that homotropic effects associated with PEP interaction do not contribute to the apparent heterotropic inhibition under these conditions (data not shown). Absent homotropic effects and by analogy to dimeric proteins, linkage theory predicts that the overall heterotropic coupling in a 4|4 tetramer, such as wild-type, should equal the sum of the 4 unique individual coupling free energies. This total can be determined in a 1|4 hybrid after correcting for the unbalanced stoichiometry by taking the fourth root of the apparent coupling (19). A comparison between the corrected total heterotropic effect of PEP on kcat/Km for Fru-6-P measured in the 1|4 hybrid to the sum of the individual heterotropic interactions obtained with the 1|1 hybrids is presented in Figure 5. The three individual inhibitory interactions very nearly account for the total observed heterotropic inhibition in the EcPFK tetramer as was the case for the heterotropic activating interactions resulting from MgADP that was determined previously (4). Inclusion of the small activation associated with the 33Å interaction reduces the total to 89±4%, suggesting that this contribution might be inconsequential within the context of the overall tetramer.

Figure 5.

The sum of the coupling free energies shown in Figure 4 compared to the total free energy of inhibition exhibited by the 1|4 control. Shadings are as defined in Figure 4. The sum of the three inhibitory interactions is given by the overall height of the left bar. The contribution of the 33Å interaction is shown subtracted from the contribution of the 23Å interaction for reasons of diagrammatic clarity. The total of the summation that includes the 33Å interaction is given by the bottom of the 33Å contribution. Error bar pertains to the sum whether or not the 33Å interaction is included.

Discussion

In this study, we have utilized the 1|1 hybrids, designed and described in previous papers to study MgADP/Fru-6-P interactions (4, 5), to individually measure each of the four unique through-protein, heterotropic PEP/Fru-6-P interactions in EcPFK. These 1|1 hybrids were constructed in 1:3 hybrid tetramers in which mutated subunits have decreased affinity for the substrate Fru-6-P as well as the allosteric effectors. Utilization of the same 1|1 hybrids that were previously designed for the study of MgADP/Fru-6-P interactions was possible since both the R21A and K213E allosteric site mutations eliminated allosteric responses to both MgADP and PEP. In addition, the K2E/K3E surface charge tag, which was added to mutated subunits to facilitate the separation of hybrid species by ion exchange, did not alter the allosteric response of MgADP or PEP.

Figure 4 and Table 1 present corrected data for each of the four unique PEP/Fru-6-P interactions in EcPFK. Comparing to the 1|4 control, the shortest interaction, 23Å, contributes the highest percent of inhibition at 42%. The 45Å and 30Å interactions contribute 25% and 31% of the inhibition, respectively. Surprisingly, in the 33Å interaction PEP acts as an activator and causes a small increase in Fru-6-P affinity. Therefore, the 33Å interaction represents −8% of the total PEP inhibition measured in the 1|4 control.

The current data suggest that two-state theories used to explain allosteric regulation are not sufficient to describe the allostery of EcPFK. Each of the four unique heterotropic interactions makes a unique, partial contribution to the total PEP inhibition. These observations do not support the concerted model in describing allosteric regulation of EcPFK (1, 20) in which the total allosteric effect is predicted to be realized in the first, single interaction regardless of its location. The common implementation of the sequential model (21) invokes equal contributions from each interaction. Instead. We observed that the three inhibitory interactions are described by coupling free energies that are significantly different from one another and the fourth contributes at most negatively to the total. Clearly the inhibition observed in this enzyme derives from multiple individual interactions that combine to produce the overall phenomenology.

Previously we have described the four unique activating interactions between MgADP and Fru-6-P in EcPFK (4). We have now accounted for 100% of the activating and nearly 100% of the inhibitory allosteric effects in this enzyme. However, the relative contribution each of the four interactions makes is different for activation and inhibition as summarized in Table 2. These differences indicate that the total allosteric effects are not derived from the same mechanisms; i.e. that activation is not simply the ‘reverse’ of the inhibition. We speculate that this may be a result of the two effectors using different communication pathways to affect the active site even though the effectors bind to the same allosteric site. The use of different communication pathways for MgADP activation and PEP inhibition in EcPFK has previously been proposed (22, 23).

Table 2.

Comparison of Coupling Free Energies for Single Heterotropic Interactions

| Enzyme | BsPFK | EcPFK | EcPFK |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allosteric Ligand | PEP | MgADP | PEP |

| Interaction | ΔGay/b (kcal/mol)a | ΔGax/b (kcal/mol)b | ΔGay/b (kcal/mol)c |

| 45Å | + 0.17 ± 0.20 | − 0.58 ± 0.01 | + 0.59±0.02 |

| 32/33Å | + 0.82 ± 0.12 | − 0.99 ± 0.03 | − 0.19±0.04 |

| 30Å | + 0.49 ± 0.11 | − 0.61 ± 0.03 | + 0.73±0.04 |

| 22/23Å | + 1.48 ± 0.15 | − 0.73 ± 0.04 | + 0.99±0.07 |

There were also differences between the relative contribution of the individual PEP/Fru-6-P interactions in EcPFK and the same interactions in BsPFK (6, 7), as summarized in Table 2. In BsPFK the shortest interaction (22Å) dominates the inhibition by PEP to a greater extent than it does for EcPFK, particularly at high pH values. The biggest difference, however, is evident in the 33Å interaction. In BsPFK, this inhibitory interaction is the second strongest whereas in Ec PFK the 33Å interaction does not contribute at all to the inhibition but rather opposes the overall inhibition slightly. In contrast, the 30Å interaction effectively vanishes at low pH in BsPFK while it is a strong participant in the inhibition of EcPFK, contributing nearly 75% as strongly as the 23Å interaction. Finally, the longest interaction (45Å) interaction makes only a small contribution to the inhibition in BsPFK whereas it contributes substantially in EcPFK. The differences in the relative contribution of the individual interactions in these two highly homologous PFK’s indicate that the pattern of allosteric perturbations between the various heterotropic sites are unique to each protein. It follows that the structural bases for the inhibition in each of these enzymes are also distinct, although we cannot predict how large these differences might be.

There are many examples of hybrid constructs being utilized to reveal important mechanistic details of allosteric responsiveness. In a series of now classic papers, Ackers and co-workers utilized selective substitution of inert metal ions, such as Zn2+, for Fe2+ to allow for selective oxygen binding within the α2β2 tetramer. These studies revealed the site-site energetic interactions that give rise to the homotropic cooperativity in oxygen binding exhibited by that protein and demonstrated that they are individually more unique than the prevailing structural data had suggested (24). Fromm and coworkers have constructed hybrids of porcine liver fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and used them to examine the heterotropic inhibition by AMP. They concluded that multiple interaction pathways exist within the homotetramer. However, in contrast to our results, they have concluded that the data can be adequately described by a concerted transition model (25). Hybrids of 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase reveal that that enzyme behaves as a dimer of dimers with each dimer exhibiting half-of the sites reactivity. Each dimer also experiences essentially independent responsiveness to the occupancy of the intra-dimer allosteric sites by the inhibitor serine, with the majority of the inhibition realized with the first binding equivalent to each dimer (26).

Taken together, the results presented herein and those obtained by other investigators suggest that the construction of hybrid enzymes provides a valuable experimental approach for revealing important insights into the mechanisms that give rise to allosteric behavior. Perhaps most importantly, all these results have confirmed that no common allosteric mechanism appears to be applicable to even the relatively few enzymes studied in the manner to date.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: PFK, phosphofructokinase; DTT, dithiothreitol; EPPS, N-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-N′-(3-propanesulfonic acid); Fru-6-P, fructose-6-phosphate; Fru-1,6-BP, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate; PEP, phospho(enol)pyruvate; EcPFK, phosphofructokinase I from Escherichia coli; BsPFK, phosphofructokinase from Bacillus stearothermophilus; G3PK, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; TIM, Triosephosphate isomerase.

As previously defined (4, 5) we use two different notations to designate hybrid PFK tetramers: x:y where x equals the number of one type of subunit (eg. wild type) and y equals the number of another type of subunit (eg. a variant derived from site-directed mutagenesis); and x|y where x equals the number of unmodified active sites and y equals the number of unmodified allosteric sites in the resultant hybrid enzyme.

Each of the four interactions, are designated by the distances between the 6′-phosphate of Fru-1,6-BP and the β-phosphate of MgADP (bound to the allosteric site) as revealed by X-ray crystallography when both ligands are bound to either EcPFK (2) or BsPFK (8). Thus, the four unique heterotropic interactions are referred to as the 45Å, 33Å, 30Å and 23Å interactions in EcPFK and the 45Å, 32Å, 30Å, and 22Å interactions in BsPFK.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM33216 and Robert A. Welch grant A1543

References

- 1.Blangy D, Buc H, Monod J. Kinetics of the Allosteric Interactions of Phosphofructokinase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1968;31:13–35. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shirakihara Y, Evans PR. Crystal Structure of the Complex of Phosphofructokinase from Escherichia coli with its Reaction Products. J Mol Biol. 1988;204:973–994. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rypniewski WR, Evans PR. Crystal Structure of Unliganded PFK from E. coli. J Mol Biol. 1989;207:805–821. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fenton AW, Paricharttanakul NM, Reinhart GD. Disentangling the Web of Allosteric Communication in a Homotetramer: Heterotropic Activation in Phosphofructokinase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14104–14110. doi: 10.1021/bi048569q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenton AW, Reinhart GD. Isolation of a Single Activating Allosteric Interaction in Phosphofructokinase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13410–13416. doi: 10.1021/bi026450g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimmel JL, Reinhart GD. Isolation of an Individual Allosteric Interaction in Tetrameric Phosphofructokinase from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11623–11629. doi: 10.1021/bi010844a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortigosa AD, Kimmel JL, Reinhart GD. Disentangling the Web of Allosteric Communication in a Homotetramer: Heterotropic Inhibition of Phosphofructokinase from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Biochemistry. 2004;43:577–586. doi: 10.1021/bi035077p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schirmer T, Evans PR. Structural Basis of the Allosteric Behaviour of Phosphofructokinase. Nature. 1990;343:140–151. doi: 10.1038/343140a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.French BA, Valdez BC, Younathan ES, Chang SH. High-level Expression of Bacillus stearothermophilus 6-phosphofructo-1-kinase in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1987;59:279–283. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90335-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daldal F. Molecular Cloning of the Gene for Phosphofructokinase-2 of Escherichia coli and the Nature of a Mutation, pfkB1, Causing a High Level of the Enzyme. J Mol Biol. 1983;168:285–305. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson JL, Lasagna MD, Reinhart GD. Influence of a Sulfhydryl Cross-Link Across the Allosteric-Site Interface of E. coli Phosphofructokinase. Protein Sci. 2001;10:2186–2194. doi: 10.1110/ps.02401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill AV. A New Mathematical Treatment of Changes of Ionic Concentration in Muscle and Nerve under the Action of Electric Currents, with a Theory as to their Mode of Excitation. J Physiol. 1910;40:190–224. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1910.sp001366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinhart GD. The Determination of Thermodynamic Allosteric Parameters of an Enzyme Undergoing Steady-State Turnover. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;225:389–401. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reinhart GD. Quantitative Analysis and Interpretation of Allosteric Behavior. Methods Enzymol. 2004;380:187–203. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)80009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson JL, Reinhart GD. Influence of MgADP on Phosphofructokinase from Escherichia coli. Elucidation of Coupling Interactions with Both Substrates. Biochemistry. 1994;33:2635–2643. doi: 10.1021/bi00175a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau FTK, Fersht AR. Dissection of the Effector-Binding Site and Complementation Studies of Escherichia coli Phosphofructokinase Using Site-Directed Mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6841–6847. doi: 10.1021/bi00443a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson JL, Reinhart GD. Failure of a Two-State Model to Describe the Influence of Phospho(enol)pyruvate on Phosphofructokinase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1997;36:12814–12822. doi: 10.1021/bi970942p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reinhart GD. Linked-Function Origins of Cooperativity in a Symmetrical Dimer. Biophys Chem. 1988;30:159–172. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(88)85013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber G. Ligand Binding and Internal Equilibria in Proteins. Biochemistry. 1972;11:864–878. doi: 10.1021/bi00755a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux JP. On the Nature of Allosteric Transitions: A Plausible Model. J Mol Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koshland DE, Jr, Nemethy G, Filmer D. Comparison of Experimental Binding Data and Theoretical Models in Proteins Containing Subunits. Biochemistry. 1966;5:365–385. doi: 10.1021/bi00865a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Auzat I, Byrnes WM, Garel JR, Chang SH. Role of Residue 161 in the Allosteric Transitions of 2 Bacterial PFKs. Biochemistry. 1995;34:7062–7068. doi: 10.1021/bi00021a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fenton AW, Paricharttanakul NM, Reinhart GD. Identification of Substrate Contact Residues Important for the Allosteric Regulation of Phosphofructokinase from Eschericia coli. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6453–6459. doi: 10.1021/bi034273t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Y, Doyle ML, Ackers GK. The Oxygen-Binding Intermediates of Human Hemoglobin: Evaluation of Their Contributions to Cooperativity Using Zinc-Containing Hybrids. Biophysical Journal. 1996;71:2094–2105. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79408-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson SW, Honzatko RB, Fromm HJ. Hybrid Tetramers of Porcine Liver Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase Reveal Multiple Pathways of Allosteric Inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15539–15545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant GA, Xu XL, Hu Z. quantitative Relationships of Site to Site Interaction in Escherichia coli D-3-Phosphoglycerate Dehydrogenase Revealed by Asymmetric Hybrid Tetramers. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13452–13460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313593200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]